Ultra-Short Peptide Hydrogels as 3D Bioprinting Materials

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Properties of Ultra-Short Peptides

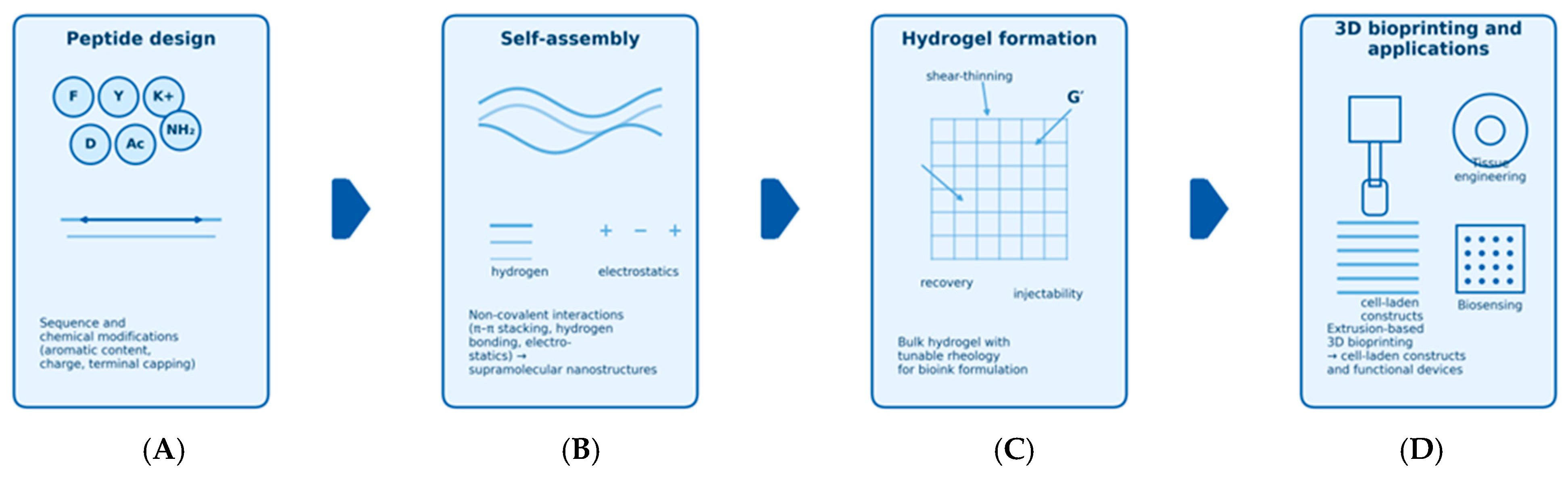

2.1. Structural Simplicity and Self-Assembly

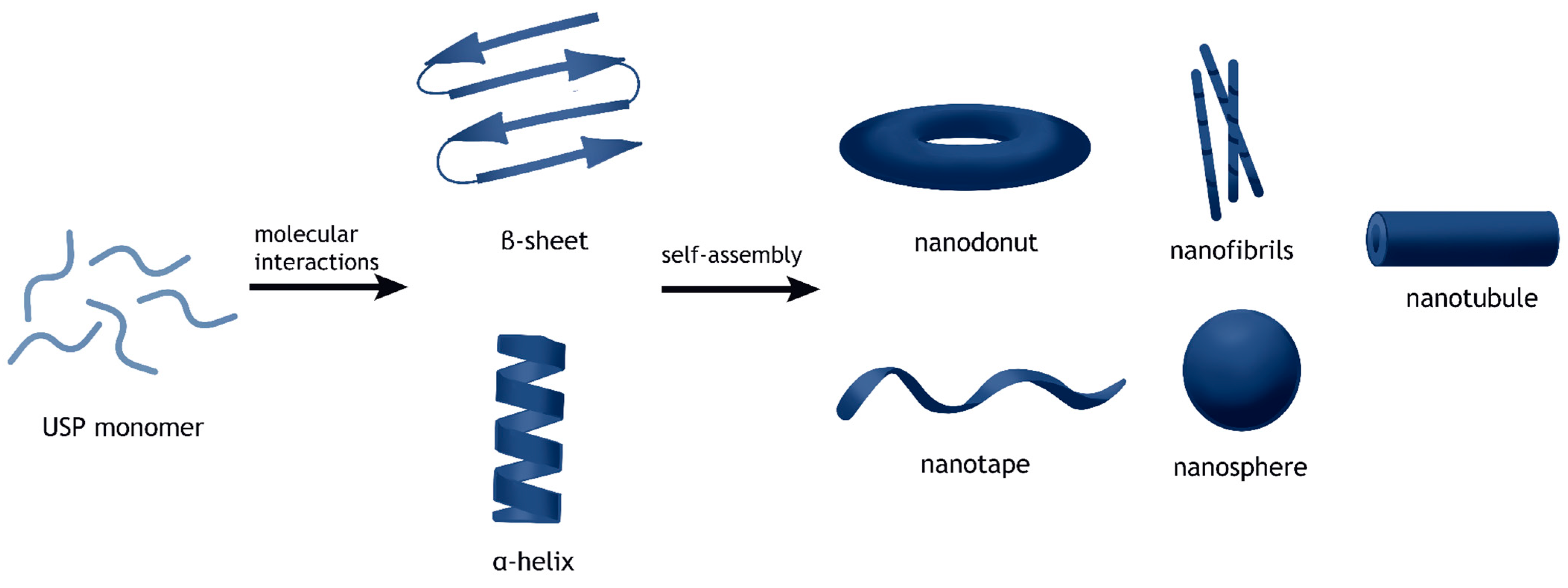

2.1.1. Nanostructures

2.1.2. Hydrogels

2.2. Biocompatibility and Biodegradability

2.3. Functional Versatility

2.4. Material Strength and Stability

2.5. Interactions with Other Materials

3. Synergies Between USPs and 3D Printing

3.1. Why USPs for 3D Printing?

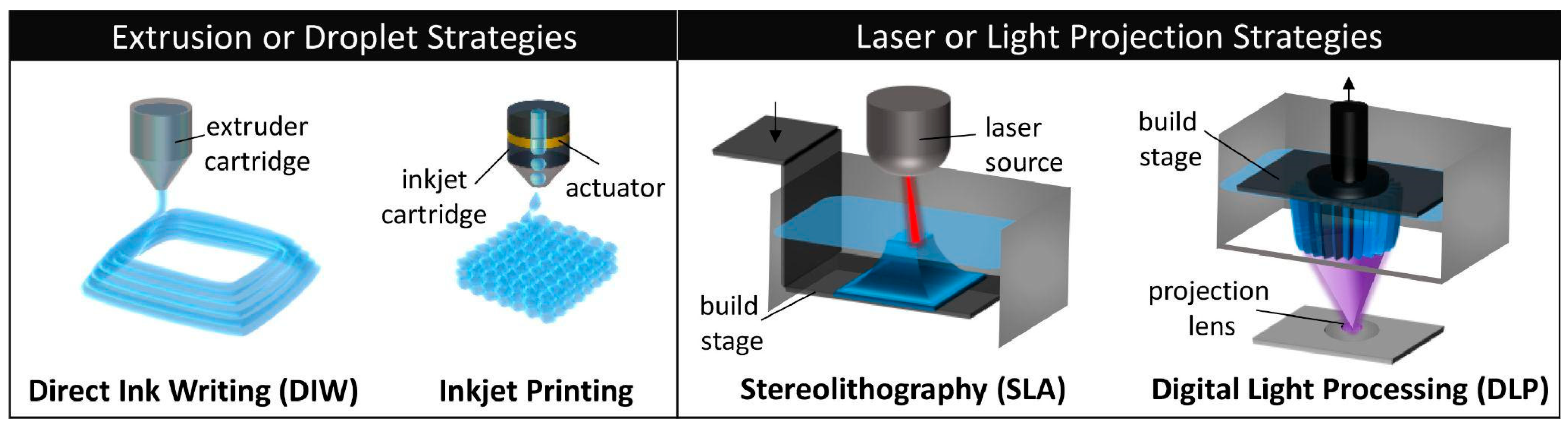

3.2. Current Methods Integrating USPs

3.3. Challenges and Opportunities

4. Applications for USPs in 3D Printing

4.1. Biomedical Applications

4.1.1. USP-Based Scaffolds for Tissue Engineering

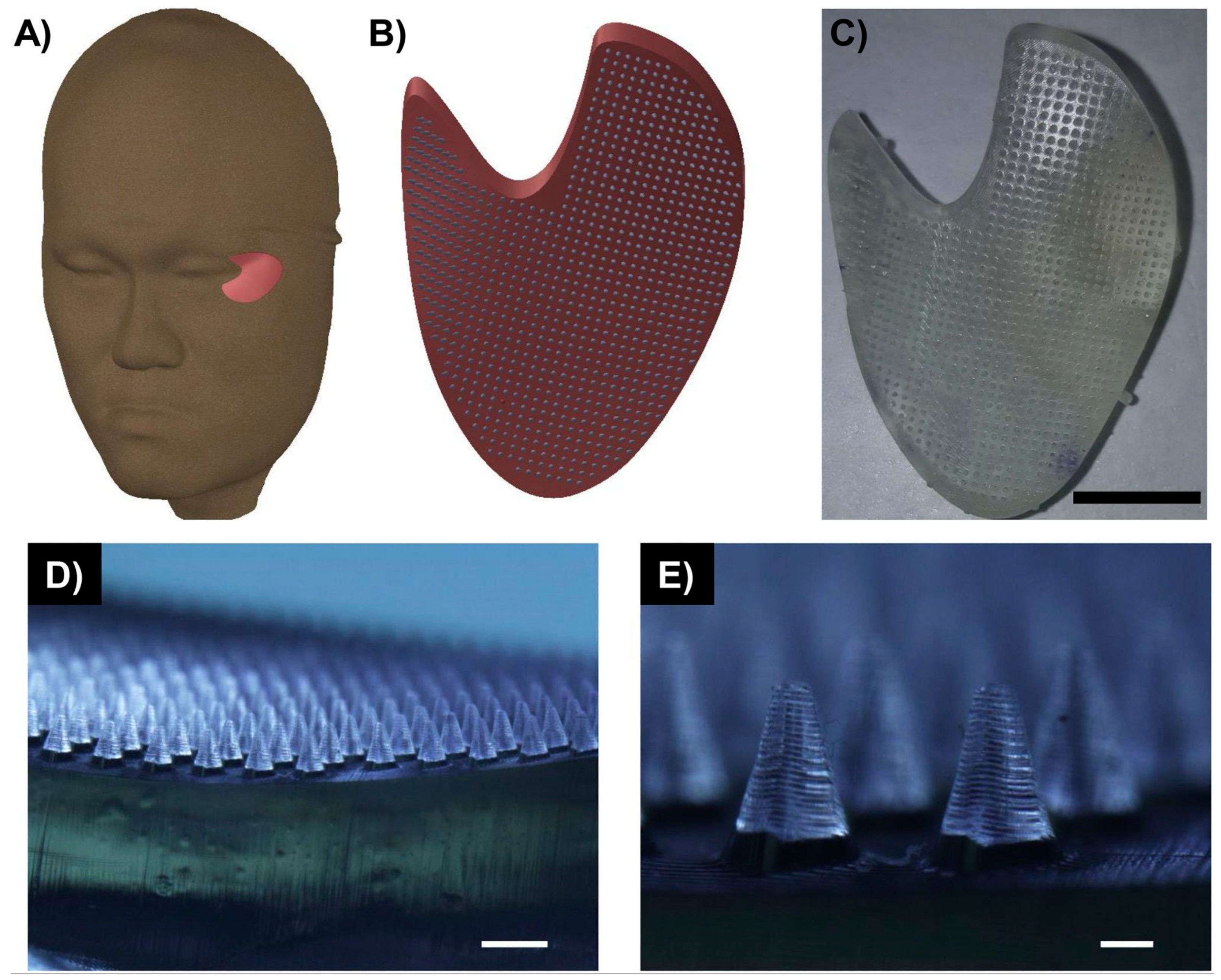

4.1.2. USPs for Drug Delivery Systems

4.1.3. USPs for Biosensors and Imaging Probes

4.2. Other Applications of 3D-Printed USP Hydrogels

5. Future Perspectives

5.1. Use of Artificial Intelligence to Design Peptides for Specific 3D Printing Applications

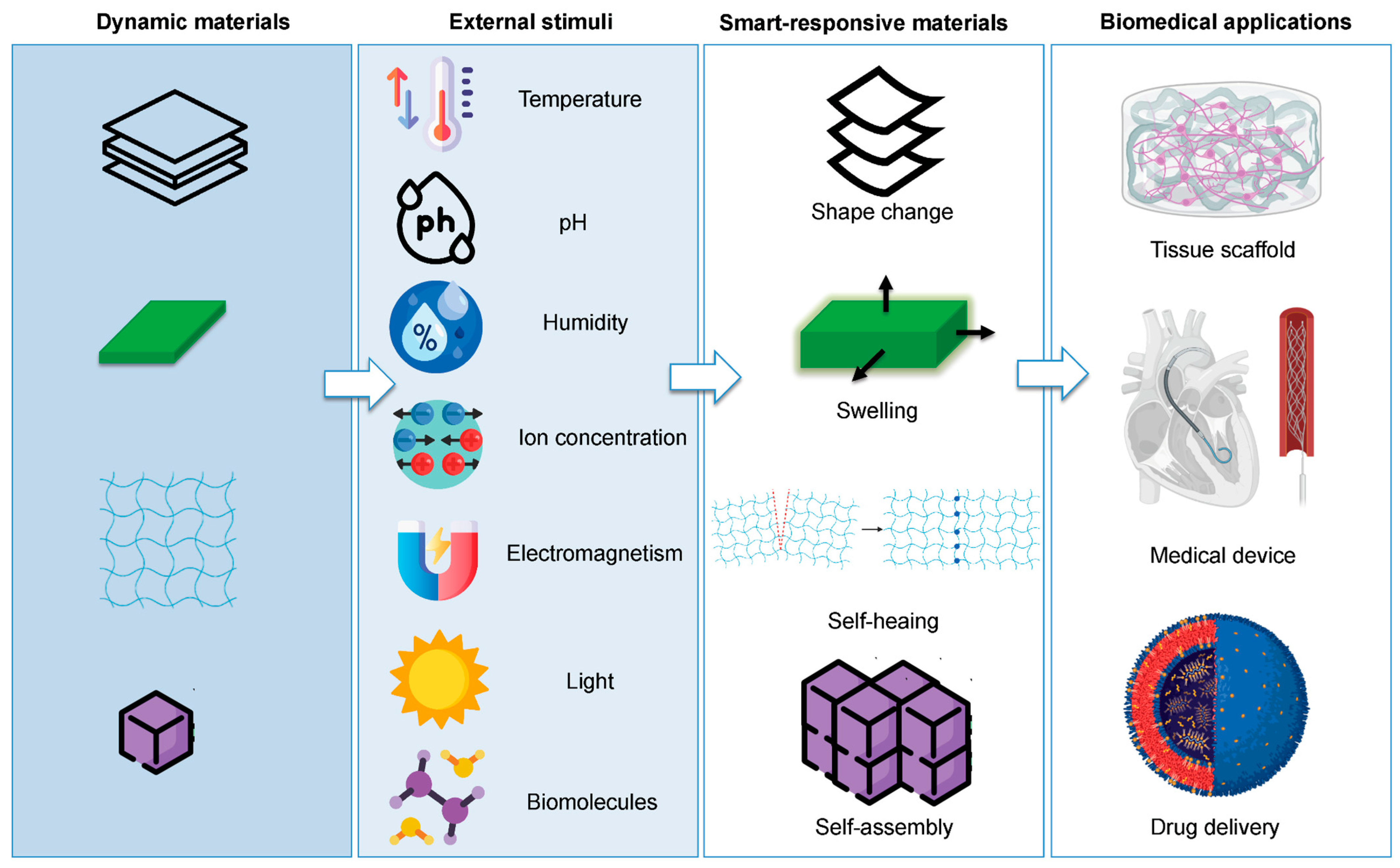

5.2. Emerging Technologies

5.2.1. Hybrid Materials Combining USPs with Other Advanced Materials

5.2.2. Multi-Material 3D Printing Techniques Using USPs

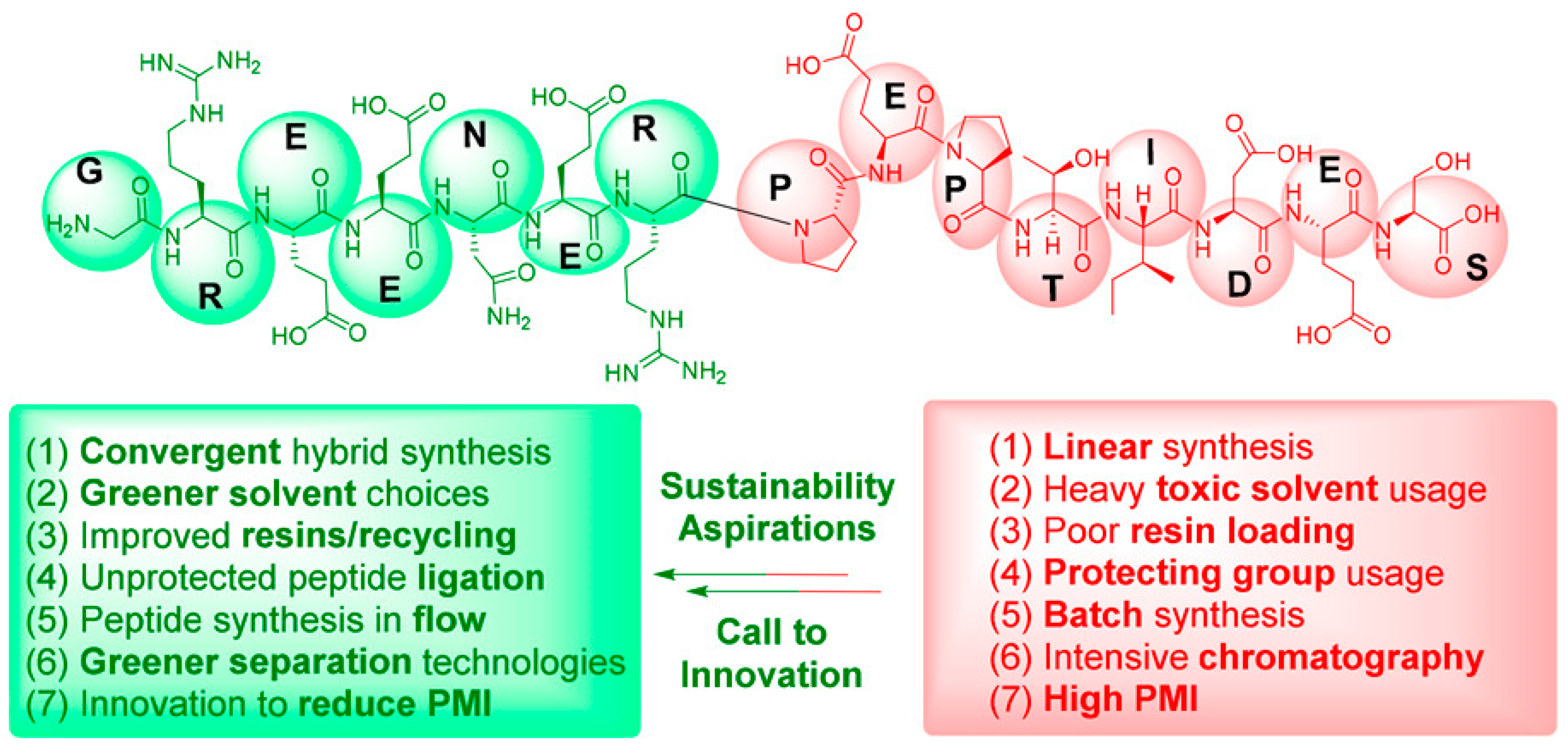

5.3. Sustainability and Scalability in USP Development

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ghalayini, S.; Susapto, H.H.; Hall, S.; Kahin, K.; Hauser, C.A.E. Preparation and Printability of Ultrashort Self-Assembling Peptide Nanoparticles. Int. J. Bioprinting 2019, 5, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giuri, D.; Ravarino, P.; Tomasini, C. Ultra-Short Peptide Nanomaterials. In Peptide Bionanomaterials; Elsawy, M.A., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 121–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, R.; Gayakvad, B.; Shinde, S.D.; Rani, J.; Jain, A.; Sahu, B. Ultrashort Peptides—A Glimpse into the Structural Modifications and Their Applications as Biomaterials. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2020, 3, 5474–5499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seow, W.Y.; Hauser, C.A.E. Short to Ultrashort Peptide Hydrogels for Biomedical Uses. Mater. Today 2014, 17, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muskan; Gupta, D.; Negi, N.P. 3D Bioprinting: Printing the Future and Recent Advances. Bioprinting 2022, 27, e00211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varpe, A.; Sayed, M.; Mane, N.S. A Comprehensive Literature Review on Advancements and Challenges in 3D Bioprinting of Human Organs: Ear, Skin, and Bone. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2025, 53, 14–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Deng, J.; Ma, B.; Tao, K.; Zhang, Z.; Ramakrishna, S.; Yuan, W.; Ye, T. Recent Advancements of Bioinks for 3D Bioprinting of Human Tissues and Organs. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2024, 7, 17–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, H.; Wang, M.; Wang, S.; Wang, A.; Bai, S. 3D Bioprinting for Cell Culture and Tissue Fabrication. Bio-Des. Manuf. 2018, 1, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiesa, I.; Ligorio, C.; Bonatti, A.F.; De Acutis, A.; Smith, A.M.; Saiani, A.; Vozzi, G.; De Maria, C. Modeling the Three-Dimensional Bioprinting Process of β-Sheet Self-Assembling Peptide Hydrogel Scaffolds. Front. Med. Technol. 2020, 2, 571626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, J.C.G.; Macías-García, A.; Rodríguez-Rego, J.M.; Mendoza-Cerezo, L.; Sánchez-Margallo, F.M.; Marcos-Romero, A.C.; Pagador-Carrasco, J.B. Optimising Bioprinting Nozzles through Computational Modelling and Design of Experiments. Biomimetics 2024, 9, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, L. Functional Hydrogel Bioink, a Key Challenge of 3D Cellular Bioprinting. APL Bioeng. 2020, 4, 030401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seol, Y.-J.; Kang, H.-W.; Lee, S.J.; Atala, A.; Yoo, J.J. Bioprinting Technology and Its Applications. Eur. J. Cardio-Thorac. Surg. 2014, 46, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loo, Y.; Hauser, C.A.E. Bioprinting Synthetic Self-Assembling Peptide Hydrogels for Biomedical Applications. Biomed. Mater. 2015, 11, 014103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhattab, D.M.; Khan, Z.; Alshehri, S.; Susapto, H.H.; Hauser, C.A.E. 3D Bioprinting of Ultrashort Self-Assembling Peptides to Engineer Scaffolds with Different Matrix Stiffness for Chondrogenesis. Int. J. Bioprinting 2024, 9, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, N.; Chauhan, M.K.; Chauhan, V.S. Short to Ultrashort Peptide-Based Hydrogels as a Platform for Biomedical Applications. Biomater. Sci. 2020, 8, 84–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortunato, A.; Mba, M. Metal Cation Triggered Peptide Hydrogels and Their Application in Food Freshness Monitoring and Dye Adsorption. Gels 2021, 7, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Pont, G.; Morris, K.; Lotze, G.; Squires, A.; Serpell, L.C.; Adams, D.J. Salt-Induced Hydrogelation of Functionalised-Dipeptides at High pH. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 12071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, M.; Zhuo, S. Applications of Self-Assembling Ultrashort Peptides in Bionanotechnology. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 844–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.; Loo, Y.; Deng, R.; Chuah, Y.J.; Hee, H.T.; Ying, J.Y.; Hauser, C.A.E. Ultrasmall Natural Peptides Self-Assemble to Strong Temperature-Resistant Helical Fibers in Scaffolds Suitable for Tissue Engineering. Nano Today 2011, 6, 232–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Singh, R.; Joshi, K.B.; Verma, S. Constitutionally Isomeric Aromatic Tripeptides: Self-Assembly and Metal-Ion-Modulated Transformations. ChemPlusChem 2020, 85, 2001–2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, H.; Wang, M.; Dong, Q.; Li, J.; Wang, A.; Li, X.; Ren, P.; Bai, S. Dipeptide Self-Assembled Hydrogels with Tunable Mechanical Properties and Degradability for 3D Bioprinting. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 46419–46426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Yu, Q.; Li, H.; Chen, M.; Jin, Y.; Liu, D. Self-Assembled Peptide Hydrogels in Regenerative Medicine. Gels 2023, 9, 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arab, W.; Hauser, C.A.E. Ultrashort Tetrameric Peptide Nanogels Support Tissue Graft Formation, Wound Healing and 3D Bioprinting. In Peptide-Based Biomaterials; Guler, M.O., Ed.; The Royal Society of Chemistry: Cambridge, UK, 2020; pp. 363–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Singh, I.; Sharma, A.K.; Kumar, P. Ultrashort Peptide Self-Assembly: Front-Runners to Transport Drug and Gene Cargos. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halder, S.; Das, T.; Kushwaha, R.; Misra, A.K.; Jana, K.; Das, D. Targeted and Precise Drug Delivery Using a Glutathione-Responsive Ultra-Short Peptide-Based Injectable Hydrogel as a Breast Cancer Cure. Mater. Horiz. 2025, 12, 987–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, K.; Xing, R.; Jiao, T.; Shen, G.; Chen, C.; Li, J.; Yan, X. Injectable Self-Assembled Dipeptide-Based Nanocarriers for Tumor Delivery and Effective In vivo Photodynamic Therapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 30759–30767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.H.; Xue, B.; Robinson, R.C.; Hauser, C.A.E. Systematic Moiety Variations of Ultrashort Peptides Produce Profound Effects on Self-Assembly, Nanostructure Formation, Hydrogelation, and Phase Transition. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 12897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, N.; Kumar, U.; Roopmani, P.; Krishnan, U.M.; Sethuraman, S.; Chauhan, M.K.; Chauhan, V.S. Ultrashort Peptide-Based Hydrogel for the Healing of Critical Bone Defects in Rabbits. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 54111–54126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thota, C.K.; Yadav, N.; Chauhan, V.S. A Novel Highly Stable and Injectable Hydrogel Based on a Conformationally Restricted Ultrashort Peptide. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 31167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basavalingappa, V.; Guterman, T.; Tang, Y.; Nir, S.; Lei, J.; Chakraborty, P.; Schnaider, L.; Reches, M.; Wei, G.; Gazit, E. Expanding the Functional Scope of the Fmoc-Diphenylalanine Hydrogelator by Introducing a Rigidifying and Chemically Active Urea Backbone Modification. Adv. Sci. 2019, 6, 1900218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurbasic, M.; Garcia, A.M.; Viada, S.; Marchesan, S. Tripeptide Self-Assembly into Bioactive Hydrogels: Effects of Terminus Modification on Biocatalysis. Molecules 2020, 26, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, N.; Atiq, A.; Rafiq, F.; Khan, I.; Atiq, M.; Saleem, M.; Anjum, D.H.; Usman, Z.; Abbas, M. Engineering of Self-Assembled Silver-Peptide Colloidal Nanohybrids with Enhanced Biocompatibility and Antibacterial Activity. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 26398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criado-Gonzalez, M.; Espinosa-Cano, E.; Rojo, L.; Boulmedais, F.; Aguilar, M.R.; Hernández, R. Injectable Tripeptide/Polymer Nanoparticles Supramolecular Hydrogel: A Candidate for the Treatment of Inflammatory Pathologies. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 10068–10080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skaat, H.; Chen, R.; Grinberg, I.; Margel, S. Engineered Polymer Nanoparticles Containing Hydrophobic Dipeptide for Inhibition of Amyloid-β Fibrillation. Biomacromolecules 2012, 13, 2662–2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Susapto, H.H.; Alhattab, D.; Abdelrahman, S.; Khan, Z.; Alshehri, S.; Kahin, K.; Ge, R.; Moretti, M.; Emwas, A.-H.; Hauser, C.A.E. Ultrashort Peptide Bioinks Support Automated Printing of Large-Scale Constructs Assuring Long-Term Survival of Printed Tissue Constructs. Nano Lett. 2021, 21, 2719–2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sedighi, M.; Shrestha, N.; Mahmoudi, Z.; Khademi, Z.; Ghasempour, A.; Dehghan, H.; Talebi, S.F.; Toolabi, M.; Préat, V.; Chen, B.; et al. Multifunctional Self-Assembled Peptide Hydrogels for Biomedical Applications. Polymers 2023, 15, 1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaliaraj, G.; Shanmugam, D.; Dasan, A.; Mosas, K. Hydrogels—A Promising Materials for 3D Printing Technology. Gels 2023, 9, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejada Jacob, G.; Passamai, V.E.; Katz, S.; Castro, G.R.; Alvarez, V. Hydrogels for Extrusion-Based Bioprinting: General Considerations. Bioprinting 2022, 27, e00212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, B.; Pei, B.; Chen, J.; Zhou, D.; Peng, J.; Zhang, X.; Jia, W.; Xu, T. Inkjet Bioprinting of Biomaterials. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 10793–10833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, H.; Zhang, T.; Xu, H.; Luo, S.; Nie, J.; Zhu, X. Photo-Curing 3D Printing Technique and Its Challenges. Bioact. Mater. 2020, 5, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, K.S.; Galarraga, J.H.; Cui, X.; Lindberg, G.C.J.; Burdick, J.A.; Woodfield, T.B.F. Fundamentals and Applications of Photo-Cross-Linking in Bioprinting. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 10662–10694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoroula, N.F.; Karavasili, C.; Vlasiou, M.C.; Primikyri, A.; Nicolaou, C.; Chatzikonstantinou, A.V.; Chatzitaki, A.-T.; Petrou, C.; Bouropoulos, N.; Zacharis, C.K.; et al. NGIWY-Amide: A Bioinspired Ultrashort Self-Assembled Peptide Gelator for Local Drug Delivery Applications. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z.; Kahin, K.; Rauf, S.; Ramirez-Calderon, G.; Papagiannis, N.; Abdulmajid, M.; Hauser, C.A.E. Optimization of a 3D Bioprinting Process Using Ultrashort Peptide Bioinks. Int. J. Bioprinting 2018, 5, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sezer, B.; Ozcan, S.; Bilgic, E.; Sunal, G.; Pulat, G.; Usta, Y.H.; Karaman, O. Peptide-Based Bioink Development for Custom-Made Bioprinter with Specialized Nozzle Design. In Proceedings of the 2022 Medical Technologies Congress (TIPTEKNO), Antalya, Turkey, 31 October–2 November 2022; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Yang, F.; Zhao, H.; Gao, Q.; Xia, B.; Fu, J. Research on the Printability of Hydrogels in 3D Bioprinting. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 29977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendes, A.C.; Baran, E.T.; Reis, R.L.; Azevedo, H.S. Self-assembly in Nature: Using the Principles of Nature to Create Complex Nanobiomaterials. WIREs Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 2013, 5, 582–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fosgerau, K.; Hoffmann, T. Peptide Therapeutics: Current Status and Future Directions. Drug Discov. Today 2015, 20, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Jian, H.; Han, Q.; Wang, A.; Li, J.; Man, N.; Li, Q.; Bai, S.; Li, J. Three-Dimensional (3D) Bioprinting of Medium Toughened Dipeptide Hydrogel Scaffolds with Hofmeister Effect. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 639, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Xuan, M.; Wang, A.; Jia, Y.; Bai, S.; Yan, X.; Li, J. Biogenic Sensors Based on Dipeptide Assemblies. Matter 2022, 5, 3643–3658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Hou, Y.; Tian, J.; Zheng, J.; Xiao, Z.; Hu, J.; Zhang, Y. d-Peptide Cell Culture Scaffolds with Enhanced Antibacterial and Controllable Release Properties. J. Mater. Chem. B 2024, 12, 8122–8132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Q.; Chang, R.; Xing, R.; Yuan, C.; Yan, X. Injectable Self-Assembled Bola-Dipeptide Hydrogels for Sustained Photodynamic Prodrug Delivery and Enhanced Tumor Therapy. J. Control. Release 2020, 319, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Guo, J.; Liu, S.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L. Empowering Hydrophobic Anticancer Drugs by Ultrashort Peptides: General Co-Assembly Strategy for Improved Solubility, Targeted Efficacy, and Clinical Application. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2024, 667, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Lv, M.; Wang, S.; Li, M.; Wang, Y.; Hu, C.; Hu, W.; Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Liu, Z.; et al. Ultrasound-Triggered Biomimetic Ultrashort Peptide Nanofiber Hydrogels Promote Bone Regeneration by Modulating Macrophage and the Osteogenic Immune Microenvironment. Bioact. Mater. 2024, 31, 231–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, R.F.; Araújo, D.R.; Silva, E.R.; Ando, R.A.; Alves, W.A. l-Diphenylalanine Microtubes as a Potential Drug-Delivery System: Characterization, Release Kinetics, and Cytotoxicity. Langmuir 2013, 29, 10205–10212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loo, Y.; Lakshmanan, A.; Ni, M.; Toh, L.L.; Wang, S.; Hauser, C.A.E. Peptide Bioink: Self-Assembling Nanofibrous Scaffolds for Three-Dimensional Organotypic Cultures. Nano Lett. 2015, 15, 6919–6925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arab, W.; Rauf, S.; Al-Harbi, O.; Hauser, C.A.E. Novel Ultrashort Self-Assembling Peptide Bioinks for 3D Culture of Muscle Myoblast Cells. Int. J. Bioprinting 2018, 4, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arab, W.; Kahin, K.; Khan, Z.; Hauser, C.A.E. Exploring Nanofibrous Self-Assembling Peptide Hydrogels Using Mouse Myoblast Cells for Three-Dimensional Bioprinting and Tissue Engineering Applications. Int. J. Bioprinting 2019, 5, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauf, S.; Susapto, H.H.; Kahin, K.; Alshehri, S.; Abdelrahman, S.; Lam, J.H.; Asad, S.; Jadhav, S.; Sundaramurthi, D.; Gao, X.; et al. Self-Assembling Tetrameric Peptides Allow in Situ 3D Bioprinting under Physiological Conditions. J. Mater. Chem. B 2021, 9, 1069–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, C.B.; Kim, Y.; Park, S.J.; Hwang, Y.; Lee, J.W. Development of Arginine-Glycine-Aspartate-Immobilized 3D Printed Poly(Propylene Fumarate) Scaffolds for Cartilage Tissue Engineering. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2018, 29, 917–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emtiazi, G.; Zohrabi, T.; Lee, L.Y.; Habibi, N.; Zarrabi, A. Covalent Diphenylalanine Peptide Nanotube Conjugated to Folic Acid/Magnetic Nanoparticles for Anti-Cancer Drug Delivery. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2017, 41, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Kaplan, J.A.; Shieh, A.; Sun, H.-L.; Croce, C.M.; Grinstaff, M.W.; Parquette, J.R. Self-Assembly of a 5-Fluorouracil-Dipeptide Hydrogel. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 5254–5257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.H.; Kathuria, H.; Amir, M.H.B.; Zhang, X.; Duong, H.T.T.; Ho, P.C.-L.; Kang, L. High Resolution Photopolymer for 3D Printing of Personalised Microneedle for Transdermal Delivery of Anti-Wrinkle Small Peptide. J. Control. Release 2021, 329, 907–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Qiu, Y.; Gao, Y. Enhanced Delivery of Hydrophilic Peptides in vitro by Transdermal Microneedle Pretreatment. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2014, 4, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Sun, L.; Huang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, M. Bioinspired Fluorescent Dipeptide Nanoparticles for Targeted Cancer Cell Imaging and Real-Time Monitoring of Drug Release. Nat. Nanotech. 2016, 11, 388–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almohammed, S.; Alruwaili, M.; Reynaud, E.G.; Redmond, G.; Rice, J.H.; Rodriguez, B.J. 3D-Printed Peptide-Hydrogel Nanoparticle Composites for Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy Sensing. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2019, 2, 5029–5034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handelman, A.; Kuritz, N.; Natan, A.; Rosenman, G. Reconstructive Phase Transition in Ultrashort Peptide Nanostructures and Induced Visible Photoluminescence. Langmuir 2016, 32, 2847–2862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Chen, M.; Lee, H.; Xu, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Feng, S.-P.; Kim, J.T. Three-Dimensional Printing of Self-Assembled Dipeptides. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 20573–20580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safaryan, S.; Slabov, V.; Kopyl, S.; Romanyuk, K.; Bdikin, I.; Vasilev, S.; Zelenovskiy, P.; Shur, V.Y.; Uslamin, E.A.; Pidko, E.A.; et al. Diphenylalanine-Based Microribbons for Piezoelectric Applications via Inkjet Printing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 10543–10551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goles, M.; Daza, A.; Cabas-Mora, G.; Sarmiento-Varón, L.; Sepúlveda-Yañez, J.; Anvari-Kazemabad, H.; Davari, M.D.; Uribe-Paredes, R.; Olivera-Nappa, Á.; Navarrete, M.A.; et al. Peptide-Based Drug Discovery through Artificial Intelligence: Towards an Autonomous Design of Therapeutic Peptides. Brief. Bioinform. 2024, 25, bbae275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, S.; Liu, T.; Lin, S.; Li, D.; Liu, H.; Yao, X.; Hou, T. Artificial Intelligence in Peptide-Based Drug Design. Drug Discov. Today 2025, 30, 104300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhou, X.; Fang, Y.; Xiong, Z.; Zhang, T. AI-Driven 3D Bioprinting for Regenerative Medicine: From Bench to Bedside. Bioact. Mater. 2025, 45, 201–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugliese, R.; Regondi, S. Artificial Intelligence-Empowered 3D and 4D Printing Technologies toward Smarter Biomedical Materials and Approaches. Polymers 2022, 14, 2794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikołajewska, E.; Mikołajewski, D.; Mikołajczyk, T.; Paczkowski, T. A Breakthrough in Producing Personalized Solutions for Rehabilitation and Physiotherapy Thanks to the Introduction of AI to Additive Manufacturing. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badini, S.; Regondi, S.; Pugliese, R. Unleashing the Power of Artificial Intelligence in Materials Design. Materials 2023, 16, 5927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopeček, J.; Yang, J. Smart Self-Assembled Hybrid Hydrogel Biomaterials. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 7396–7417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Lu, X.-M.; Zhang, M.-R.; Hu, K.; Li, Z. Peptide-Based Nanomaterials: Self-Assembly, Properties and Applications. Bioact. Mater. 2022, 11, 268–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozhin, P.; Charitidis, C.; Marchesan, S. Self-Assembling Peptides and Carbon Nanomaterials Join Forces for Innovative Biomedical Applications. Molecules 2021, 26, 4084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamzehlou, S.; Aboudzadeh, M.A. Special Issue on “Multifunctional Hybrid Materials Based on Polymers: Design and Performance”. Processes 2021, 9, 1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Wang, M.; Wang, T.; Sun, M.; Huang, H.; Shi, X.; Duan, S.; Wu, Y.; Zhu, J.; Liu, F. Self-Assembled Short Peptides: Recent Advances and Strategies for Potential Pharmaceutical Applications. Mater. Today Bio 2023, 20, 100644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trombetta, R.; Inzana, J.A.; Schwarz, E.M.; Kates, S.L.; Awad, H.A. 3D Printing of Calcium Phosphate Ceramics for Bone Tissue Engineering and Drug Delivery. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2017, 45, 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, A.; Gokcekaya, O.; Md Masum Billah, K.; Ertugrul, O.; Jiang, J.; Sun, J.; Hussain, S. Multi-Material Additive Manufacturing: A Systematic Review of Design, Properties, Applications, Challenges, and 3D Printing of Materials and Cellular Metamaterials. Mater. Des. 2023, 226, 111661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, R.D.; Garcia, R.V.; Heise, A.; Hawker, C.J. Peptides as 3D Printable Feedstocks: Design Strategies and Emerging Applications. Progress Polym. Sci. 2022, 124, 101487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbazi, M.; Jäger, H.; Ettelaie, R.; Mohammadi, A.; Asghartabar Kashi, P. Multimaterial 3D Printing of Self-Assembling Smart Thermo-Responsive Polymers into 4D Printed Objects: A Review. Addit. Manuf. 2023, 71, 103598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zhong, Z.; Hu, N.; Zhou, Y.; Maggio, L.; Miri, A.K.; Fragasso, A.; Jin, X.; Khademhosseini, A.; Zhang, Y.S. Coaxial Extrusion Bioprinting of 3D Microfibrous Constructs with Cell-Favorable Gelatin Methacryloyl Microenvironments. Biofabrication 2018, 10, 024102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manzano, J.S.; Wang, H.; Slowing, I.I. High Throughput Screening of 3D Printable Resins: Adjusting the Surface and Catalytic Properties of Multifunctional Architectures. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2019, 1, 2890–2896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muralidharan, A.; McLeod, R.R.; Bryant, S.J. Hydrolytically Degradable Poly(Β-amino Ester) Resins with Tunable Degradation for 3D Printing by Projection Micro-Stereolithography. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2106509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grigoryan, B.; Sazer, D.W.; Avila, A.; Albritton, J.L.; Padhye, A.; Ta, A.H.; Greenfield, P.T.; Gibbons, D.L.; Miller, J.S. Development, Characterization, and Applications of Multi-Material Stereolithography Bioprinting. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 3171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, A.; Wei, G. Designed Graphene-Peptide Nanocomposites for Biosensor Applications: A Review. Anal. Chim. Acta 2017, 985, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isidro-Llobet, A.; Kenworthy, M.N.; Mukherjee, S.; Kopach, M.E.; Wegner, K.; Gallou, F.; Smith, A.G.; Roschangar, F. Sustainability Challenges in Peptide Synthesis and Purification: From R&D to Production. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 84, 4615–4628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Kumar, A.; De La Torre, B.G.; Albericio, F. Liquid-Phase Peptide Synthesis (LPPS): A Third Wave for the Preparation of Peptides. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 13516–13546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.T.; Leferink, N.G.H.; Scrutton, N.S. Chemo-Enzymatic Routes towards the Synthesis of Bio-Based Monomers and Polymers. Mol. Catal. 2019, 467, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grillo, G.; Cintas, P.; Colia, M.; Calcio Gaudino, E.; Cravotto, G. Process Intensification in Continuous Flow Organic Synthesis with Enabling and Hybrid Technologies. Front. Chem. Eng. 2022, 4, 966451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study/Ref. | Peptide Length | Printing Modality | Key Printability/Mechanical Features | Cell Type(s) | Cell Response |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loo et al. [55] | Hexapeptide USPs | Extrusion-based 3D bioprinting | Instant gelation under physiological conditions; printed scaffolds maintain structural integrity during and after printing | Human mesenchymal stem cells | High viability; differentiation into skin- and intestinal-like organotypic tissue constructs |

| Arab et al. [56,57] | IVFK, IVZK tetrapeptides | Extrusion-based 3D bioprinting | Good printability: ECM-mimicking nanofibrous networks that entrap aqueous media | C2C12 mouse myoblast cells; muscle myoblast cells | Enhanced adhesion and proliferation; promotion of myogenic differentiation into muscle fibers |

| Susapto et al. [35] | Tetrapeptides IIFK, IIZK, IZZK | Extrusion-based 3D bioprinting | Transparent hydrogels even at 0.1% w/v; desirable stiffness and shape fidelity; instant solidification during printing | Human dermal fibroblasts; human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells | Supports neuron growth; maintains viability and structural integrity over weeks; chondrogenic development |

| Alhattab et al. [14] | Tetrapeptides IIZK, IZZK | In vivo bioprinting/cartilage fabrication | Self-assembly into nanofibrous hydrogels under physiological conditions; suitable for minimally invasive delivery | Human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells | Biocompatible scaffolds: differentiation of HBMSCs into chondrocytes |

| Jian et al. [21] | Dipeptides Fmoc-YD, Fmoc-YK, and mixtures | Extrusion-based printing of hydrogels | Tunable mechanics and biodegradability via concentration and mixing ratio; mixed system reported > 5× strength increase at specific ratios | HepaRG cells (human hepatic cells) | Supports cell growth; tunable degradation and shape fidelity |

| Rauf et al. [58] | Tetrapeptides IVZK (Ac-Ile-Val-Cha-Lys-NH2) and IVFK (Ac-Ile-Val-Phe-Lys-NH2) | In situ extrusion-based 3D bioprinting under physiological conditions | Durable constructs; good printability and stability under physiological conditions | Human dermal fibroblasts; human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells | High biocompatibility; maintenance of viability within printed scaffolds |

| Khan et al. [43] | Tetrapeptides IVZK/IVFK | Robotic extrusion 3D bioprinting with vacuum assistance | Vacuum-assisted system improves print resolution; enables ~40 mm cylindrical constructs with lower water content and improved stability | Human dermal fibroblasts | Constructs suitable for cartilage tissue engineering |

| Ahn et al. [59] | PPF-based ink with immobilized RGD tripeptide | Micro-stereolithography | Macroporous 3D scaffolds with controlled architecture; photocross-linkable system provides high shape fidelity | Human chondrocytes | Improved cell–matrix interaction; potential for cartilage tissue regeneration |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

In, D.; Miliotou, A.N.; Siafaka, P.I.; Sarigiannis, Y. Ultra-Short Peptide Hydrogels as 3D Bioprinting Materials. Gels 2026, 12, 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010049

In D, Miliotou AN, Siafaka PI, Sarigiannis Y. Ultra-Short Peptide Hydrogels as 3D Bioprinting Materials. Gels. 2026; 12(1):49. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010049

Chicago/Turabian StyleIn, Davina, Androulla N. Miliotou, Panoraia I. Siafaka, and Yiannis Sarigiannis. 2026. "Ultra-Short Peptide Hydrogels as 3D Bioprinting Materials" Gels 12, no. 1: 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010049

APA StyleIn, D., Miliotou, A. N., Siafaka, P. I., & Sarigiannis, Y. (2026). Ultra-Short Peptide Hydrogels as 3D Bioprinting Materials. Gels, 12(1), 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010049