Hydrogels for Osteochondral Interface Regeneration: Biomaterial Types, Processes, and Animal Models

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Hydrogel Biomaterials for OCI Regeneration

3. Techniques Used to Process Hydrogels

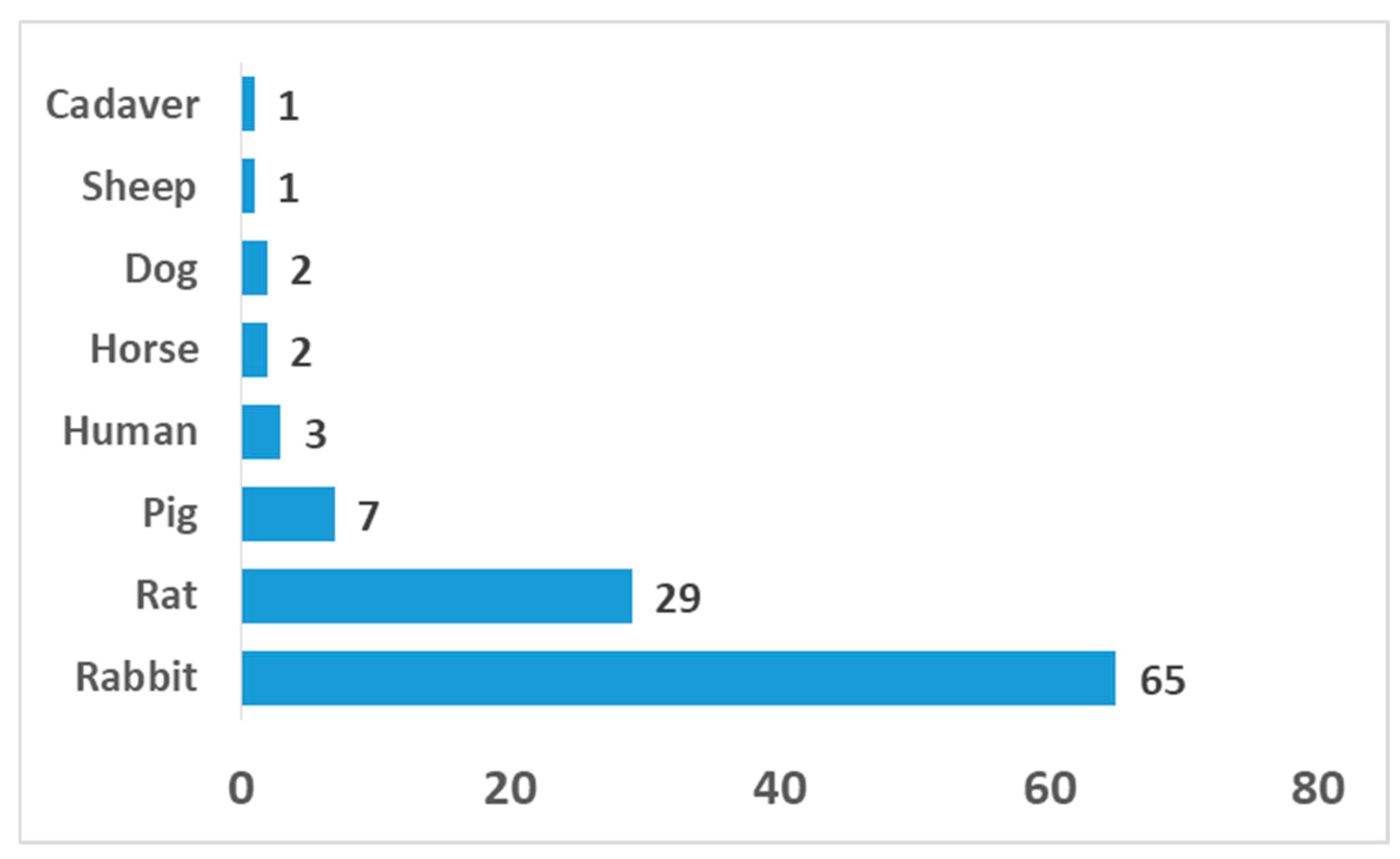

4. Animal Models for OCI Interface Regeneration

5. Authors’ Views: Emerging Trends, Technological Gaps, and Requirements for Translational or GMP Readiness

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cheng, H.-w.; Luk, K.D.K.; Cheung, K.M.C.; Chan, B.P. In vitro generation of an osteochondral interface from mesenchymal stem cell–collagen microspheres. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 1526–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, N.; Amanzhanova, A.; Kulzhanova, G.; Mukasheva, F.; Erisken, C. Osteochondral Interface: Regenerative Engineering and Challenges. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2023, 9, 1205–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, T.J.; McClure, S.F.; Stoddart, R.W.; McClure, J. The normal human chondro-osseous junctional region: Evidence for contact of uncalcified cartilage with subchondral bone and marrow spaces. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2006, 7, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvorak, J.; Junge, A.; Derman, W.; Schwellnus, M. Injuries and illnesses of football players during the 2010 FIFA World Cup. Br. J. Sports Med. 2011, 45, 626–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, I.; Miot, S.; Barbero, A.; Jakob, M.; Wendt, D. Osteochondral tissue engineering. J. Biomech. 2007, 40, 750–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valtanen, R.S.; Yang, Y.P.; Gurtner, G.C.; Maloney, W.J.; Lowenberg, D.W. Synthetic and Bone tissue engineering graft substitutes: What is the future? Injury 2021, 52, S72–S77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farokhi, M.; Jonidi Shariatzadeh, F.; Solouk, A.; Mirzadeh, H. Alginate Based Scaffolds for Cartilage Tissue Engineering: A Review. Int. J. Polym. Mater. Polym. Biomater. 2020, 69, 230–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, J.M.; Rodrigues, M.T.; Silva, S.S.; Malafaya, P.B.; Gomes, M.E.; Viegas, C.A.; Dias, I.R.; Azevedo, J.T.; Mano, J.F.; Reis, R.L. Novel hydroxyapatite/chitosan bilayered scaffold for osteochondral tissue-engineering applications: Scaffold design and its performance when seeded with goat bone marrow stromal cells. Biomaterials 2006, 27, 6123–6137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asensio, G.; Benito-Garzón, L.; Ramírez-Jiménez, R.A.; Guadilla, Y.; Gonzalez-Rubio, J.; Abradelo, C.; Parra, J.; Martín-López, M.R.; Aguilar, M.R.; Vázquez-Lasa, B.; et al. Biomimetic Gradient Scaffolds Containing Hyaluronic Acid and Sr/Zn Folates for Osteochondral Tissue Engineering. Polymers 2021, 14, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira Vasconcelos, D.; Leite Pereira, C.; Couto, M.; Neto, E.; Ribeiro, B.; Albuquerque, F.; Freitas, A.; Alves, C.J.; Klinkenberg, G.; McDonagh, B.H.; et al. Nanoenabled Immunomodulatory Scaffolds for Cartilage Tissue Engineering. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2400627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effanga, V.E.; Akilbekova, D.; Mukasheva, F.; Zhao, X.; Kalyon, D.M.; Erisken, C. In Vitro Investigation of 3D Printed Hydrogel Scaffolds with Electrospun Tidemark Component for Modeling Osteochondral Interface. Gels 2024, 10, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erisken, C.; Kalyon, D.M.; Wang, H.; Örnek-Ballanco, C.; Xu, J. Osteochondral tissue formation through adipose-derived stromal cell differentiation on biomimetic polycaprolactone nanofibrous scaffolds with graded insulin and Beta-glycerophosphate concentrations. Tissue Eng. Part A 2011, 17, 1239–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayrak, E.; Ozcan, B.; Erisken, C. Processing of polycaprolactone and hydroxyapatite to fabricate graded electrospun composites for tendon-bone interface regeneration. J. Polym. Eng. 2017, 37, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erisken, C.; Kalyon, D.M.; Wang, H. Functionally graded electrospun polycaprolactone and β-tricalcium phosphate nanocomposites for tissue engineering applications. Biomaterials 2008, 29, 4065–4073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erisken, C.; Kalyon, D.M.; Wang, H. A hybrid twin screw extrusion/electrospinning method to process nanoparticle-incorporated electrospun nanofibres. Nanotechnology 2008, 19, 165302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergun, A.; Chung, R.; Ward, D.; Valdevit, A.; Ritter, A.; Kalyon, D.M. Unitary bioresorbable cage/core bone graft substitutes for spinal arthrodesis coextruded from polycaprolactone biocomposites. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2012, 40, 1073–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozkan, S.; Kalyon, D.M.; Yu, X. Functionally graded β-TCP/PCL nanocomposite scaffolds: In vitro evaluation with human fetal osteoblast cells for bone tissue engineering. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2010, 92A, 1007–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tourlomousis, F.; Jia, C.; Karydis, T.; Mershin, A.; Wang, H.; Kalyon, D.M.; Chang, R.C. Machine learning metrology of cell confinement in melt electrowritten three-dimensional biomaterial substrates. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 2019, 5, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.E.; Kim, A.R.; Lee, C.J.; Tripathy, N.; Yoon, K.H.; Lee, D.; Khang, G. Effects of purified alginate sponge on the regeneration of chondrocytes: In vitro and in vivo. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2015, 26, 181–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Huang, H.; Hao, G.; Zhang, Y.; Ding, H.; Fan, Z.; Sun, L. 3D Printing Hydrogel Scaffolds with Nanohydroxyapatite Gradient to Effectively Repair Osteochondral Defects in Rats. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 202006697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.; Li, S.; Yu, K.; He, B.; Hong, J.; Xu, T.; Meng, J.; Ye, C.; Chen, Y.; Shi, Z.; et al. A 3D-printed PRP-GelMA hydrogel promotes osteochondral regeneration through M2 macrophage polarization in a rabbit model. Acta Biomater. 2021, 128, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Zhu, F.; Li, X.; Liang, Q.; Zhuo, Z.; Huang, J.; Duan, L.; Xiong, J.; Wang, D. Repair of osteochondral defects using injectable chitosan-based hydrogel encapsulated synovial fluid-derived mesenchymal stem cells in a rabbit model. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2019, 99, 541–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yucekul, A.; Ozdil, D.; Kutlu, N.H.; Erdemli, E.; Aydin, H.M.; Doral, M.N. Tri-layered composite plug for the repair of osteochondral defects: In vivo study in sheep. J. Tissue Eng. 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruvinov, E.; Tavor Re’em, T.; Witte, F.; Cohen, S. Articular cartilage regeneration using acellular bioactive affinity-binding alginate hydrogel: A 6-month study in a mini-pig model of osteochondral defects. J. Orthop. Transl. 2019, 16, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Girolamo, L.; Niada, S.; Arrigoni, E.; Di Giancamillo, A.; Domeneghini, C.; Dadsetan, M.; Yaszemski, M.J.; Gastaldi, D.; Vena, P.; Taffetani, M.; et al. Repair of osteochondral defects in the minipig model by OPF hydrogel loaded with adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Regen. Med. 2015, 10, 135–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kon, E.; Mutini, A.; Arcangeli, E.; Delcogliano, M.; Filardo, G.; Nicoli Aldini, N.; Pressato, D.; Quarto, R.; Zaffagnini, S.; Marcacci, M. Novel nanostructured scaffold for osteochondral regeneration: Pilot study in horses. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2010, 4, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, E.A.; Michelacci, Y.M.; Baccarin, R.Y.; Cogliati, B.; CLC Silva, L. Evaluation of Chitosan-GP Hydrogel Biocompatibility in Osteochondral Defects: An experimental Approach. BMC Vet. Res. 2014, 10, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribitsch, I.; Baptista, P.M.; Lange-Consiglio, A.; Melotti, L.; Patruno, M.; Jenner, F.; Schnabl-Feichter, E.; Dutton, L.C.; Connolly, D.J.; van Steenbeek, F.G.; et al. Large Animal Models in Regenerative Medicine and Tissue Engineering: To Do or Not to Do. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erisken, C.; Kalyon, D.M.; Wang, H. Viscoelastic and biomechanical properties of osteochondral tissue constructs generated from graded polycaprolactone and beta-tricalcium phosphate composites. J. Biomech. Eng. 2010, 132, 091013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karami, P.; Laurent, A.; Philippe, V.; Applegate, L.A.; Pioletti, D.P.; Martin, R. Cartilage Repair: Promise of Adhesive Orthopedic Hydrogels. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, A.; Ling, C.; Sheng, R.; Li, X.; Yao, Q.; Chen, J. Enzymatically crosslinked silk-nanosilicate reinforced hydrogel with dual-lineage bioactivity for osteochondral tissue engineering. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2021, 127, 112215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, F.; Xu, Z.; Liang, Q.; Li, H.; Peng, L.; Wu, M.; Zhao, X.; Cui, X.; Ruan, C.; Liu, W. Osteochondral Regeneration with 3D-Printed Biodegradable High-Strength Supramolecular Polymer Reinforced-Gelatin Hydrogel Scaffolds. Adv. Sci. 2019, 6, 201900867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miljkovic, N.D.; Lin, Y.C.; Cherubino, M.; Minteer, D.; Marra, K.G. A novel injectable hydrogel in combination with a surgical sealant in a rat knee osteochondral defect model. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2009, 17, 1326–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, F.; Yang, X.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, Y.; Yuan, X. Photocrosslinked layered gelatin-chitosan hydrogel with graded compositions for osteochondral defect repair. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2015, 26, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Ding, X.; Yu, X.; Chen, X.; Zhang, X.; Cui, S.; Shi, J.; Chen, J.; Yu, L.; Chen, S.; et al. Cell-Free Bilayered Porous Scaffolds for Osteochondral Regeneration Fabricated by Continuous 3D-Printing Using Nascent Physical Hydrogel as Ink. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2021, 10, 202001404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartnikowski, M.; Akkineni, A.R.; Gelinsky, M.; Woodruff, M.A.; Klein, T.J. A hydrogel model incorporating 3D-plotted hydroxyapatite for osteochondral tissue engineering. Materials 2016, 9, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Hong, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yang, L.; Li, J.; Jiang, D.; Bunpetch, V.; Hu, Y.; Ouyang, H.; Zhang, S. Tough hydrogel with enhanced tissue integration and in situ forming capability for osteochondral defect repair. Appl. Mater. Today 2018, 13, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, D.; Wang, Z.; Xie, C.; Wang, X.; Xing, W.; Ge, X.; Yuan, H.; Wang, K.; Tan, H.; Lu, X. Mussel-Inspired Tough Hydrogel with In Situ Nanohydroxyapatite Mineralization for Osteochondral Defect Repair. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2019, 8, 201901103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, L.; Li, D.; Wang, W.; Zhang, Q.; Zhou, X.; Liu, D.; Zhang, J.; You, Z.; Zhang, J.; He, C. Bilayered Scaffold Prepared from a Kartogenin-Loaded Hydrogel and BMP-2-Derived Peptide-Loaded Porous Nanofibrous Scaffold for Osteochondral Defect Repair. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 5, 4564–4573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.; Li, W.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Li, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, L.; Liu, T. Development and fabrication of a two-layer tissue engineered osteochondral composite using hybrid hydrogel-cancellous bone scaffolds in a spinner flask. Biomed. Mater. 2016, 11, 065002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, K.; Li, L.; Yan, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, R.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, H.; Liu, T. Fabrication and development of artificial osteochondral constructs based on cancellous bone/hydrogel hybrid scaffold. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2016, 27, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, Z.; Lian, M.; Han, Y.; Sun, B.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, W.; Li, H.; Hao, Y.; Dai, K. Bioinspired stratified electrowritten fiber-reinforced hydrogel constructs with layer-specific induction capacity for functional osteochondral regeneration. Biomaterials 2021, 266, 120385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Yao, H.; Sun, H.; Gu, Z.; Hu, X.; Yang, J.; Shi, J.; Yang, H.; Dai, J.; Chong, H.; et al. Enhanced hyaline cartilage formation and continuous osteochondral regeneration via 3D-Printed heterogeneous hydrogel with multi-crosslinking inks. Mater. Today Bio 2024, 26, 101080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Alcala-Orozco, C.R.; Baer, K.; Li, J.; Murphy, C.A.; Durham, M.; Lindberg, G.; Hooper, G.J.; Lim, K.S.; Woodfield, T.B.F. 3D bioassembly of cell-instructive chondrogenic and osteogenic hydrogel microspheres containing allogeneic stem cells for hybrid biofabrication of osteochondral constructs. Biofabrication 2022, 14, 034101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.; Zhang, L.; Yu, Y.; Yan, W.; Zhao, F.; Fan, Y.; Cao, C.; Cai, Q.; Hu, X.; Ao, Y. 3D Bioprinting of Heterogeneous Constructs Providing Tissue-Specific Microenvironment Based on Host–Guest Modulated Dynamic Hydrogel Bioink for Osteochondral Regeneration. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2200710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Huang, J.; Li, X.; Zhao, W.; Hua, Y.; Song, Z.; Wang, X.; Guo, Z.; Zhou, G.; Ren, W.; et al. Trilayered biomimetic hydrogel scaffolds with dual-differential microenvironment for articular osteochondral defect repair. Mater. Today Bio 2024, 26, 101051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Yan, Z.; Yuan, X.; Tian, G.; Wu, J.; Fu, L.; Yin, H.; He, S.; Ning, C.; Zheng, Y.; et al. Apoptotic extracellular vesicles derived from hypoxia-preconditioned mesenchymal stem cells within a modified gelatine hydrogel promote osteochondral regeneration by enhancing stem cell activity and regulating immunity. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2024, 22, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Shang, Y.; Sun, W.; Ouyang, X.; Zhou, W.; Lu, J.; Yang, S.; Wei, W.; Yao, X.; Wang, X.; et al. Seamless and early gap healing of osteochondral defects by autologous mosaicplasty combined with bioactive supramolecular nanofiber-enabled gelatin methacryloyl (BSN-GelMA) hydrogel. Bioact. Mater. 2023, 19, 88–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Xiao, H.; Zhang, H.; Xin, Q.; Zhang, H.; Liu, H.; Wu, M.; Zuo, L.; Luo, J.; Guo, Q.; et al. Heterogenous hydrogel mimicking the osteochondral ECM applied to tissue regeneration. J. Mater. Chem. B 2021, 9, 8646–8658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, L.; Han, Z.; Li, X. Tannic Acid-mediated Multifunctional 3D Printed Composite Hydrogel for Osteochondral Regeneration. Int. J. Bioprint. 2022, 8, 220–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Dai, W.; Gao, C.; Wei, W.; Huang, R.; Zhang, X.; Yu, Y.; Yang, X.; Cai, Q. Multileveled Hierarchical Hydrogel with Continuous Biophysical and Biochemical Gradients for Enhanced Repair of Full-Thickness Osteochondral Defect. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, 2209565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schagemann, J.C.; Erggelet, C.; Chung, H.W.; Lahm, A.; Kurz, H.; Mrosek, E.H. Cell-laden and cell-free biopolymer hydrogel for the treatment of osteochondral defects in a sheep model. Tissue Eng. Part A 2009, 15, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahangir, S.; Vecstaudza, J.; Augurio, A.; Canciani, E.; Stipniece, L.; Locs, J.; Alini, M.; Serra, T. Cell-Laden 3D Printed GelMA/HAp and THA Hydrogel Bioinks: Development of Osteochondral Tissue-like Bioinks. Materials 2023, 16, 7214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Huang, R.; Xia, J.; Hu, X.; Xie, D.; Jin, Y.; Qi, W.; Zhao, C.; Hu, Z. A nanozyme-functionalized bilayer hydrogel scaffold for modulating the inflammatory microenvironment to promote osteochondral regeneration. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2024, 22, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iseki, T.; Rothrauff, B.B.; Kihara, S.; Overholt, K.J.; Taha, T.; Lin, H.; Alexander, P.G.; Tuan, R.S. Enhanced osteochondral repair by leukocyte-depleted platelet-rich plasma in combination with adipose-derived mesenchymal stromal cells encapsulated in a three-dimensional photocrosslinked injectable hydrogel in a rabbit model. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2024, 15, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, J.; Li, Y.; Qin, Y.; Huang, Z.; Wu, Y.; Sun, L.; Wang, C.; Wang, W.; Feng, G.; Qi, Y. In Situ Deposition of Drug and Gene Nanoparticles on a Patterned Supramolecular Hydrogel to Construct a Directionally Osteochondral Plug. Nano-Micro Lett. 2024, 16, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Guo, Q.; Liu, C.; Bai, J.; Wang, H.; Li, J.; Liu, D.; Yu, Q.; Shi, J.; Liu, C.; et al. Cytomodulin-10 modified GelMA hydrogel with kartogenin for in-situ osteochondral regeneration. Acta Biomater. 2023, 169, 317–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Liu, G.; Wang, B.; Meng, H.; Bahatibieke, A.; Li, J.F.; Ma, M.; Peng, J.; Zheng, Y. An injectable self-healing alginate hydrogel with desirable mechanical and degradation properties for enhancing osteochondral regeneration. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 343, 122424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Wang, X.; Gao, C.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Q.; Pei, Y.; Wang, H.; Tang, Y.; Li, K.; Yu, Y.; et al. Biodegradable Piezoelectric-Conductive Integrated Hydrogel Scaffold for Repair of Osteochondral Defects. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2409400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Lee, E.; Huh, S.J.; Kang, J., II; Park, K.M.; Byun, H.; Lee, S.; Kim, E.; Shin, H. Composite Spheroid-Laden Bilayer Hydrogel for Engineering Three-Dimensional Osteochondral Tissue. Tissue Eng. Part A 2024, 30, 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heng, C.; Zhou, Y.; Luo, H.; Pan, H.; Cui, X.; Wei, X.; Chen, L.; Xie, X. Hydroxyapatite injectable hydrogel with nanozyme activity for improved immunoregulation microenvironment and accelerated osteochondral defects repair via mild photothermal therapy. Biomater. Adv. 2026, 178, 214462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Cui, Y.; Li, P.; Sun, X.; Chen, Z.; Wang, J.; Gu, X.; Wang, X.; Fan, Y. Continuous mechanical-gradient hydrogel with on-demand distributed Mn2+/Mg-doped hydroxyapatite@Fe3O4 for functional osteochondral regeneration. Bioact. Mater. 2025, 49, 608–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, Z.; Xu, H.; Guo, M.; Xu, W.; Wen, Y.; Sun, F.; Zhang, T.; Peng, B.; Zhao, P.; Huang, L.; et al. A soft-hard hybrid scaffold for osteochondral regeneration through integration of composite hydrogel and biodegradable magnesium. Biomaterials 2026, 324, 123493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Li, H.; Xu, Z.; Yue, Z.; Chen, S.; Fu, Q.; Chen, Y. Immune regulation and repair of osteochondral defects using manganese-luteolin hydrogel scaffold. J. Control. Release 2025, 384, 113920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Ji, X.; Xue, Y.; Yang, W.; Zhong, G.; Zhou, Z.; Chen, X.; Lei, Z.; Lu, T.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Immune-modulated adhesive hydrogel for enhancing osteochondral graft adhesion and cartilage repair. Bioact. Mater. 2025, 49, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries-van Melle, M.L.; Tihaya, M.S.; Kops, N.; Koevoet, W.J.L.M.; Mary Murphy, J.; Verhaar, J.A.N.; Alini, M.; Eglin, D.; van Osch, G.J.V.M. Chondrogenic differentiation of human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in a simulated osteochondral environment is hydrogel dependent. Eur. Cells Mater. 2014, 27, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanarian, N.T.; Jiang, J.; Wan, L.Q.; Mow, V.C.; Lu, H.H. A hydrogel-mineral composite scaffold for osteochondral interface tissue engineering. Tissue Eng. Part A 2012, 18, 533–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorovich, N.E.; Schuurman, W.; Wijnberg, H.M.; Prins, H.J.; Van Weeren, P.R.; Malda, J.; Alblas, J.; Dhert, W.J.A. Biofabrication of osteochondral tissue equivalents by printing topologically defined, cell-laden hydrogel scaffolds. Tissue Eng. Part C Methods 2012, 18, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radhakrishnan, J.; Manigandan, A.; Chinnaswamy, P.; Subramanian, A.; Sethuraman, S. Gradient nano-engineered in situ forming composite hydrogel for osteochondral regeneration. Biomaterials 2018, 162, 82–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, X.; Hu, X.; Shao, Z.; Dai, L.; Ju, X.; Ao, Y.; Wang, J. CaAlg hydrogel containing bone morphogenetic protein 4-enhanced adipose-derived stem cells combined with osteochondral mosaicplasty facilitated the repair of large osteochondral defects. Knee Surg. Sport. Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2019, 27, 3668–3678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Z.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, H.; Nie, Y.; Xu, S. Gradient Mineralized and Porous Double-Network Hydrogel Effectively Induce the Differentiation of BMSCs into Osteochondral Tissue In Vitro for Potential Application in Cartilage Repair. Macromol. Biosci. 2021, 21, 202000323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Zhao, T.; Qi, Y.; Luo, J.; Fang, J.; Yang, X.; Liu, X.; Xu, T.; Yang, Q.; Gou, Z.; et al. In vitro Chondrocyte Responses in Mg-doped Wollastonite/Hydrogel Composite Scaffolds for Osteochondral Interface Regeneration. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 17911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Chen, T.; Feng, B.; Weng, J.; Duan, K.; Wang, J.; Lu, X. Biomimetic Bacterial Cellulose-Enhanced Double-Network Hydrogel with Excellent Mechanical Properties Applied for the Osteochondral Defect Repair. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 4, 3534–3544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, Q.; Xu, X.; Zhang, S.; Chen, Y.; Yuan, T.; Zeng, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Mei, Z.; Yan, S.; et al. Functionalized Microscaffold-Hydrogel Composites Accelerating Osteochondral Repair through Endochondral Ossification. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 52599–52617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Fang, Z.; Wang, B.; Li, J.; Bahatibieke, A.; Meng, H.; Xie, Y.; Peng, J.; Zheng, Y. Dual cross-linked polyurethane-alginate biomimetic hydrogel for elastic gradient simulation in osteochondral structures: Microenvironment modulation and tissue regeneration. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 281, 136215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saygili, E.; Saglam-Metiner, P.; Cakmak, B.; Alarcin, E.; Beceren, G.; Tulum, P.; Kim, Y.W.; Gunes, K.; Eren-Ozcan, G.G.; Akakin, D.; et al. Bilayered laponite/alginate-poly(acrylamide) composite hydrogel for osteochondral injuries enhances macrophage polarization: An in vivo study. Biomater. Adv. 2022, 134, 112721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Dong, Q.; Zhao, X.; Sun, Y.; Lin, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, T.; Yang, T.; Jiang, X.; Li, J.; et al. Honeycomb-like biomimetic scaffold by functionalized antibacterial hydrogel and biodegradable porous Mg alloy for osteochondral regeneration. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 1417742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhan, L.; Zhang, B.; Wo, H.; Wu, L.; Li, H.; Liu, M.; Li, Z.; Chen, T.; Gui, X.; Wang, K.; et al. DLP-printed biomimetic dual-layer scaffold based on SilMA hydrogel with controlled release of chondrocytes for osteochondral defect reconstruction. Biomater. Adv. 2025, 177, 214404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filová, E.; Tonar, Z.; Lukášová, V.; Buzgo, M.; Litvinec, A.; Rampichová, M.; Beznoska, J.; Plencner, M.; Staffa, A.; Daňková, J.; et al. Hydrogel containing anti-cd44-labeled microparticles, guide bone tissue formation in osteochondral defects in rabbits. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, T.; Gao, S.; Ye, K.; Zhou, F.; Qiu, D.; Wang, X.; Tian, Y.; Qu, X. Biphasic Double-Network Hydrogel With Compartmentalized Loading of Bioactive Glass for Osteochondral Defect Repair. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 00752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, C.; Réthoré, G.; Weiss, P.; d’Arros, C.; Lesoeur, J.; Vinatier, C.; Halgand, B.; Geffroy, O.; Fusellier, M.; Vaillant, G.; et al. A Self-Setting Hydrogel of Silylated Chitosan and Cellulose for the Repair of Osteochondral Defects: From in vitro Characterization to Preclinical Evaluation in Dogs. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 00023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baysan, G.; Yilmaz, P.A.; Albayrak, A.Z.; Havitcioglu, H. Loofah and poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) (PHBV) nano-fiber-reinforced chitosan hydrogel composite scaffolds with elderberry (Sambucus nigra) and hawthorn (Crataegus oxyacantha) extracts as additives for osteochondral tissue engineering applications. Polym. Bull. 2024, 81, 10255–10276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.H.; Wang, H.C.; Tseng, Y.L.; Yeh, M.L. A bioactive composite scaffold enhances osteochondral repair by using thermosensitive chitosan hydrogel and endothelial lineage cell-derived chondrogenic cell. Mater. Today Bio 2024, 28, 101174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Guo, S.; Jiao, J.; Li, L. A Biphasic Hydrogel with Self-Healing Properties and a Continuous Layer Structure for Potential Application in Osteochondral Defect Repair. Polymers 2023, 15, 2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Wang, H.; Huang, W.; Peng, K.; Shi, R.; Tian, W.; Lin, L.; Yuan, J.; Yao, W.; Ma, X.; et al. A natural polymer-based hydrogel with shape controllability and high toughness and its application to efficient osteochondral regeneration. Mater. Horiz. 2023, 10, 3797–3806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Shao, H.; Li, X.; Ullah, M.W.; Luo, G.; Xu, Z.; Ma, L.; He, X.; Lei, Z.; Li, Q.; et al. Injectable immunomodulation-based porous chitosan microspheres/HPCH hydrogel composites as a controlled drug delivery system for osteochondral regeneration. Biomaterials 2022, 285, 121530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Chen, M.; Bai, J.; Chen, T.; He, S.; Peng, W.; Wang, J.; Zhi, W.; Weng, J. A bionic composite hydrogel with dual regulatory functions for the osteochondral repair. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2022, 219, 112821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, T.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Wang, S.; Liu, X.; Jin, H.; Zhao, Z. Microstructurally and mechanically tunable acellular hydrogel scaffold using carboxymethyl cellulose for potential osteochondral tissue engineering. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 253, 126658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, T.H.; Wang, H.C.; Wu, M.C.; Hsu, H.C.; Yeh, M.L. A bilineage thermosensitive hydrogel system for stimulation of mesenchymal stem cell differentiation and enhancement of osteochondral regeneration. Compos. Part B Eng. 2022, 233, 109614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gang, F. A high-strength, toughness, self-recovery hydrogel for potential osteochondral repair. Mater. Lett. 2022, 307, 131064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Deng, H.; Dong, Y.; Wu, X.; Xia, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, L.; Huang, Z.; Xu, W.; Xu, P.; et al. Double-Network Bilayer Hydrogel Loaded with Puerarin and Curcumin for Osteochondral Repair. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 42282–42299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Y.B.; Ha, C.W.; Lee, C.H.; Park, Y.G. Restoration of a large osteochondral defect of the knee using a composite of umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells and hyaluronic acid hydrogel: A case report with a 5-year follow-up. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2017, 18, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Este, M.; Sprecher, C.M.; Milz, S.; Nehrbass, D.; Dresing, I.; Zeiter, S.; Alini, M.; Eglin, D. Evaluation of an injectable thermoresponsive hyaluronan hydrogel in a rabbit osteochondral defect model. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2016, 104, 1469–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Liu, Y.; He, L.; Wang, Q.; Wang, L.; Yuan, T.; Xiao, Y.; Fan, Y.; Zhang, X. Icariin conjugated hyaluronic acid/collagen hydrogel for osteochondral interface restoration. Acta Biomater. 2018, 74, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, B.J.; Arai, Y.; Choi, B.; Park, S.; Ahn, J.; Han, I.B.; Lee, S.H. Restoration of articular osteochondral defects in rat by a bi-layered hyaluronic acid hydrogel plug with TUDCA-PLGA microsphere. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2018, 61, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, Y.H.; Hsieh, M.F.; Fang, C.H.; Jiang, C.P.; Lin, B.; Lee, H.M. Osteochondral Regeneration Induced by TGF-β Loaded Photo Cross-Linked Hyaluronic Acid Hydrogel Infiltrated in Fused Deposition-Manufactured Composite Scaffold of Hydroxyapatite and Poly (Ethylene Glycol)-Block-Poly(ε-Caprolactone). Polymers 2017, 9, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, I.A.D.; Schmidt, S.; Brommer, H.; Pouran, B.; Schäfer, S.; Tessmar, J.; Mensinga, A.; Van Rijen, M.H.P.; Groll, J.; Blunk, T.; et al. A composite hydrogel-3D printed thermoplast osteochondral anchor as example for a zonal approach to cartilage repair: In vivo performance in a long-term equine model. Biofabrication 2020, 12, 035028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, S.; Xu, G.; Zheng, Z.; Chen, T.; Huang, Y. Repair of Osteochondral Defect with Acellular Cartilage Matrix and Thermosensitive Hydrogel Scaffold. Tissue Eng. Part A 2025, 31, 1015–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xu, Y.; Wang, P.; Ma, J.; Wang, P.; Han, X.; Fan, Y.; Bai, D.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, X. Cell-mediated injectable blend hydrogel-BCP ceramic scaffold for in situ condylar osteochondral repair. Acta Biomater. 2021, 123, 364–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lei, Y.; Wang, N.; Zhang, J.; Cui, W.; Luo, X. Increased physiological osteochondral repair via space-specific sequestrating endogenous BMP-2 founctional hydrogel. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 501, 157687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bichara, D.A.; Bodugoz-Sentruk, H.; Ling, D.; Malchau, E.; Bragdon, C.R.; Muratoglu, O.K. Osteochondral defect repair using a polyvinyl alcohol-polyacrylic acid (PVA-PAAc) hydrogel. Biomed. Mater. 2014, 9, 045012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leone, G.; Volpato, M.D.; Nelli, N.; Lamponi, S.; Boanini, E.; Bigi, A.; Magnani, A. Continuous multilayered composite hydrogel as osteochondral substitute. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2015, 103, 2521–2530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batista, N.A.; Rodrigues, A.A.; Bavaresco, V.P.; Mariolani, J.R.L.; Belangero, W.D. Polyvinyl alcohol hydrogel irradiated and acetalized for osteochondral defect repair: Mechanical, chemical, and histological evaluation after implantation in rat knees. Int. J. Biomater. 2012, 2012, 582685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Queiroz, A.A.B.; Debieux, P.; Amaro, J.; Ferretti, M.; Cohen, M. Hydrogel implant is as effective as osteochondral autologous transplantation for treating focal cartilage knee injury in 24 months. Knee Surg. Sport. Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2018, 26, 2934–2941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sismondo, R.A.; Werner, F.W.; Ordway, N.R.; Osaheni, A.O.; Blum, M.M.; Scuderi, M.G. The use of a hydrogel implant in the repair of osteochondral defects of the knee: A biomechanical evaluation of restoration of native contact pressures in cadaver knees. Clin. Biomech. 2019, 67, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, T.P.; Ursolino, A.P.S.; Casagrande, P.d.M.; Caetano, E.B.; Mistura, D.V.; Duek, E.A.d.R. In vivo evaluation of porous hydrogel pins to fill osteochondral defects in rabbits. Rev. Bras. Ortop. (Engl. Ed.) 2017, 52, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, W.; Xu, M.; Qin, M.; Cheng, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, D.; Wei, X.; Guo, Y.; Chen, W. Physicochemical properties and biocompatibility of the bi-layer polyvinyl alcohol-based hydrogel for osteochondral tissue engineering. Mater. Des. 2021, 204, 109652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Chen, T.; Wang, Y.; Bai, J.; Lao, C.; Luo, M.; Chen, M.; Peng, W.; Zhi, W.; Weng, J.; et al. Piezoelectric Effect of Antibacterial Biomimetic Hydrogel Promotes Osteochondral Defect Repair. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, X.J.; Ling, T.X.; Xiao, Q.; Chen, Z.X.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, J.G.; Zhou, Z.K. Integrated 3D printing of topologically hierarchical mechanical hydrogel for accelerating osteochondral regeneration. Bioact. Mater. 2026, 55, 679–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Geng, X.; Wang, X.; Yang, X.; Li, F.; Li, Z.; Xu, L.; Qiu, D.; Tian, H. An Osteochondral Tissue-Mimicking Hydrogel-Scaffold Di-Block Patch for Rapid Repair of Focal Load-Bearing Cartilage Lesions. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2025, 14, e2500253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, T.A.; Bodde, E.W.H.; Baggett, L.S.; Tabata, Y.; Mikos, A.G.; Jansen, J.A. Osteochondral repair in the rabbit model utilizing bilayered, degradable oligo(poly(ethylene glycol) fumarate) hydrogel scaffolds. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2005, 75, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Park, H.; Young, S.; Kretlow, J.D.; van den Beucken, J.J.; Baggett, L.S.; Tabata, Y.; Kasper, F.K.; Mikos, A.G.; Jansen, J.A. Repair of osteochondral defects with biodegradable hydrogel composites encapsulating marrow mesenchymal stem cells in a rabbit model. Acta Biomater. 2010, 6, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Park, H.; Liu, G.; Liu, W.; Cao, Y.; Tabata, Y.; Kasper, F.K.; Mikos, A.G. In vitro generation of an osteochondral construct using injectable hydrogel composites encapsulating rabbit marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 2741–2752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.; Lam, J.; Lu, S.; Spicer, P.P.; Lueckgen, A.; Tabata, Y.; Wong, M.E.; Jansen, J.A.; Mikos, A.G.; Kasper, F.K. Osteochondral tissue regeneration using a bilayered composite hydrogel with modulating dual growth factor release kinetics in a rabbit model. J. Control. Release 2013, 168, 166–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Lam, J.; Trachtenberg, J.E.; Lee, E.J.; Seyednejad, H.; van den Beucken, J.J.J.P.; Tabata, Y.; Wong, M.E.; Jansen, J.A.; Mikos, A.G.; et al. Dual growth factor delivery from bilayered, biodegradable hydrogel composites for spatially-guided osteochondral tissue repair. Biomaterials 2014, 35, 8829–8839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, J.H.; Ren, X.; Afizah, M.H.; Chian, K.S.; Mikos, A.G. Oligo[poly(ethylene glycol)fumarate] hydrogel enhances osteochondral repair in porcine femoral condyle defects knee. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2013, 471, 1174–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, S.; Lam, J.; Trachtenberg, J.E.; Lee, E.J.; Seyednejad, H.; Van Den Beucken, J.J.J.P.; Tabata, Y.; Kasper, F.K.; Scott, D.W.; Wong, M.E.; et al. Technical Report: Correlation Between the Repair of Cartilage and Subchondral Bone in an Osteochondral Defect Using Bilayered, Biodegradable Hydrogel Composites. Tissue Eng. Part C Methods 2015, 21, 1216–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, M.; Lin, R.; Yun, S.; Du, Y.; Wang, L.; Yao, Q.; Zannettino, A.; Zhang, H. Allogeneic primary mesenchymal stem/stromal cell aggregates within poly(N-isopropylacrylamide-co-acrylic acid) hydrogel for osteochondral regeneration. Appl. Mater. Today 2020, 18, 100487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinmetz, N.J.; Aisenbrey, E.A.; Westbrook, K.K.; Qi, H.J.; Bryant, S.J. Mechanical loading regulates human MSC differentiation in a multi-layer hydrogel for osteochondral tissue engineering. Acta Biomater. 2015, 21, 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, B.; Li, Q.; Dong, H.; Huang, T.; Cao, X.; Liao, H. Bilayered HA/CS/PEGDA hydrogel with good biocompatibility and self-healing property for potential application in osteochondral defect repair. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2018, 34, 1016–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilmoth, R.L.; Ferguson, V.L.; Bryant, S.J. A 3D, Dynamically Loaded Hydrogel Model of the Osteochondral Unit to Study Osteocyte Mechanobiology. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2020, 9, 2001226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, S.; Chen, P.; Chen, Y.; Li, M.; Chen, C.; Lu, H. 3D-Printed Extracellular Matrix/Polyethylene Glycol Diacrylate Hydrogel Incorporating the Anti-inflammatory Phytomolecule Honokiol for Regeneration of Osteochondral Defects. Am. J. Sports Med. 2020, 48, 2808–2818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; Zhang, Q.; Yu, C.; Zhu, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Gu, T.; Ye, L.; Yang, W.; Ying, X.; Xu, Y.; et al. Continuous-Gradient Mineralized Hydrogel Synthesized via Gravitational Osmosis for Osteochondral Defect Repair. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 202408249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Qiu, M.; Zheng, Y.; Shi, X.; Yang, J. Biomimetic injectable and bilayered hydrogel scaffold based on collagen and chondroitin sulfate for the repair of osteochondral defects. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 257, 128593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; Tian, T.; Shi, S.; Xie, X.; Ma, Q.; Li, G.; Lin, Y. The fabrication of biomimetic biphasic CAN-PAC hydrogel with a seamless interfacial layer applied in osteochondral defect repair. Bone Res. 2017, 5, 17018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckstein, K.N.; Hergert, J.E.; Uzcategui, A.C.; Schoonraad, S.A.; Bryant, S.J.; McLeod, R.R.; Ferguson, V.L. Controlled Mechanical Property Gradients Within a Digital Light Processing Printed Hydrogel-Composite Osteochondral Scaffold. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2024, 52, 2162–2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, D.R.; Canadas, R.F.; Silva-Correia, J.; da Silva Morais, A.; Oliveira, M.B.; Dias, I.R.; Mano, J.F.; Marques, A.P.; Reis, R.L.; Oliveira, J.M. Injectable gellan-gum/hydroxyapatite-based bilayered hydrogel composites for osteochondral tissue regeneration. Appl. Mater. Today 2018, 12, 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.H.; Kim, N.; Rim, M.A.; Lee, W.; Song, J.E.; Khang, G. Characterization and Potential of a Bilayered Hydrogel of Gellan Gum and Demineralized Bone Particles for Osteochondral Tissue Engineering. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 34703–34715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietryga, K.; Reczyńska-Kolman, K.; Reseland, J.E.; Haugen, H.; Larreta-Garde, V.; Pamuła, E. Biphasic monolithic osteochondral scaffolds obtained by diffusion-limited enzymatic mineralization of gellan gum hydrogel. Biocybern. Biomed. Eng. 2023, 43, 189–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, J.; Peng, X.; Li, A.; Chen, M.; Ding, Y.; Xu, X.; Yu, P.; Xie, J.; Li, J. Gellan gum/alginate-based Ca-enriched acellular bilayer hydrogel with robust interface bonding for effective osteochondral repair. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 270, 118382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, Y.; Xiong, X.; Cui, R.; Zhang, G.; Wang, C.; Xiao, D.; Qu, S.; Weng, J. Hybridizing gellan/alginate and thixotropic magnesium phosphate-based hydrogel scaffolds for enhanced osteochondral repair. Mater. Today Bio 2022, 14, 100261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y.; Xiao, M.; Almaqrami, B.S.; Kang, H.; Shao, Z.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Y. Regenerated silk fibroin based on small aperture scaffolds and marginal sealing hydrogel for osteochondral defect repair. Biomater. Res. 2023, 27, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Wang, H.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Y.; Mo, Q.; Zhang, P.; Wang, M.; Liu, H.; Bao, X.; Sun, Y.; et al. Silk-based hydrogel incorporated with metal-organic framework nanozymes for enhanced osteochondral regeneration. Bioact. Mater. 2023, 20, 221–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Cao, Z.; Mo, Q.; Sheng, R.; Ling, C.; Chi, J.; Yao, Q.; Chen, J.; et al. Multifunctional polyphenol-based silk hydrogel alleviates oxidative stress and enhances endogenous regeneration of osteochondral defects. Mater. Today Bio 2022, 14, 100251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Xiang, X.; Song, M.; Shen, J.; Shi, Z.; Huang, W.; Liu, H. An all-silk-derived bilayer hydrogel for osteochondral tissue engineering. Mater. Today Bio 2022, 17, 100485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Qin, X.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, T.; Wang, X.; Li, J.; Yin, P.; Yu, Y.; Liu, C. Dual-Gradient Silk-Based Hydrogel for Spatially Targeted Delivery and Osteochondral Regeneration. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, 2420394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.H.; Jiang, J.; Tang, A.; Hung, C.T.; Guo, X.E. Development of Controlled Heterogeneity on a Polymer-Ceramic Hydrogel Scaffold for Osteochondral Repair. Key Eng. Mater. 2005, 284–286, 607–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Tang, A.; Ateshian, G.A.; Edward Guo, X.; Hung, C.T.; Lu, H.H. Bioactive stratified polymer ceramic-hydrogel scaffold for integrative osteochondral repair. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2010, 38, 2183–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollenstein, J.; Terrier, A.; Cory, E.; Chen, A.C.; Sah, R.L.; Pioletti, D.P. Mechanical evaluation of a tissue-engineered zone of calcification in a bone–hydrogel osteochondral construct. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Engin. 2015, 18, 332–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yokota, M.; Yasuda, K.; Kitamura, N.; Arakaki, K.; Onodera, S.; Kurokawa, T.; Gong, J.P. Spontaneous hyaline cartilage regeneration can be induced in an osteochondral defect created in the femoral condyle using a novel double-network hydrogel. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2011, 12, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higa, K.; Kitamura, N.; Goto, K.; Kurokawa, T.; Gong, J.P.; Kanaya, F.; Yasuda, K. Effects of osteochondral defect size on cartilage regeneration using a double-network hydrogel. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2017, 18, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wada, S.; Kitamura, N.; Nonoyama, T.; Kiyama, R.; Kurokawa, T.; Gong, J.P.; Yasuda, K. Hydroxyapatite-coated double network hydrogel directly bondable to the bone: Biological and biomechanical evaluations of the bonding property in an osteochondral defect. Acta Biomater. 2016, 44, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Lyu, J.; Xing, F.; Chen, R.; Duan, X.; Xiang, Z. A biphasic, demineralized, and Decellularized allograft bone-hydrogel scaffold with a cell-based BMP-7 delivery system for osteochondral defect regeneration. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2020, 108, 1909–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Liu, C.; Tu, C.; Zhang, R.; Tang, X.; Li, H.; Wang, H.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, H.; et al. Hydrogel-hydroxyapatite-monomeric collagen type-I scaffold with low-frequency electromagnetic field treatment enhances osteochondral repair in rabbits. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2021, 12, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Zhou, T.; Xu, P.; Ye, J.; Gou, Z.; Gao, C. Enhanced regeneration of osteochondral defects by using an aggrecanase-1 responsively degradable and N-cadherin mimetic peptide-conjugated hydrogel loaded with BMSCs. Biomater. Sci. 2020, 8, 2212–2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, F.; Li, Y.; Wang, L.; Che, H.; Zhang, X.; Jahr, H.; Wang, L.; Jiang, D.; Huang, H.; Wang, J. Full-thickness osteochondral defect repair using a biodegradable bilayered scaffold of porous zinc and chondroitin sulfate hydrogel. Bioact. Mater. 2024, 32, 400–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasuda, K.; Kitamura, N.; Gong, J.P.; Arakaki, K.; Kwon, H.J.; Onodera, S.; Chen, Y.M.; Kurokawa, T.; Kanaya, F.; Ohmiya, Y.; et al. A novel double-network hydrogel induces spontaneous articular cartilage regeneration in vivo in a large osteochondral defect. Macromol. Biosci. 2009, 9, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koushki, N.; Katbab, A.A.; Tavassoli, H.; Jahanbakhsh, A.; Majidi, M.; Bonakdar, S. A new injectable biphasic hydrogel based on partially hydrolyzed polyacrylamide and nanohydroxyapatite as scaffold for osteochondral regeneration. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 9089–9096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Zhang, Z.C.; Yuan, F.Z.; Deng, R.H.; Yan, X.; Mao, F.B.; Chen, Y.R.; Lu, H.; Yu, J.K. An immunomodulatory polypeptide hydrogel for osteochondral defect repair. Bioact. Mater. 2023, 19, 678–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Xu, Z.; Liang, Q.; Liu, B.; Li, H.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, Z.; Wu, M.; Ruan, C.; et al. Direct 3D Printing of High Strength Biohybrid Gradient Hydrogel Scaffolds for Efficient Repair of Osteochondral Defect. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28, 201706644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Shi, Z.; Zong, H.; Zhang, K.; Yan, S.; Yin, J. Injectable, self-healing poly(amino acid)-hydrogel based on phenylboronate ester bond for osteochondral tissue engineering. Biomed. Mater. 2023, 18, 055001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pipino, G.; Risitano, S.; Alviano, F.; WU, E.J.; Bonsi, L.; Vaccarisi, D.C.; Indelli, P.F. Microfractures and hydrogel scaffolds in the treatment of osteochondral knee defects: A clinical and histological evaluation. J. Clin. Orthop. Trauma 2019, 10, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipriani, F.; Ariño Palao, B.; Gonzalez De Torre, I.; Vega Castrillo, A.; Aguado Hernández, H.J.; Alonso Rodrigo, M.; Àlvarez Barcia, A.J.; Sanchez, A.; García Diaz, V.; Lopez Peña, M.; et al. An elastin-like recombinamer-based bioactive hydrogel embedded with mesenchymal stromal cells as an injectable scaffold for osteochondral repair. Regen. Biomater. 2019, 6, 335–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarsenova, M.; Raimagambetov, Y.; Issabekova, A.; Karzhauov, M.; Kudaibergen, G.; Akhmetkarimova, Z.; Batpen, A.; Ramankulov, Y.; Ogay, V. Regeneration of Osteochondral Defects by Combined Delivery of Synovium-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells, TGF-β1 and BMP-4 in Heparin-Conjugated Fibrin Hydrogel. Polymers 2022, 14, 5343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/devicesatfda/index.cfm (accessed on 6 December 2025).

- Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT03679208?term=chitosan-based%20injectable&rank=1 (accessed on 6 December 2025).

- Qin, C.; Li, H.; Xiao, Q.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, J.; Du, Y. Water-solubility of chitosan and its antimicrobial activity. Carbohydr. Polym. 2006, 63, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.H.; Rodeo, S.A.; Fortier, L.A.; Lu, C.; Erisken, C.; Mao, J.J. Protein-releasing polymeric scaffolds induce fibrochondrocytic differentiation of endogenous cells for knee meniscus regeneration in sheep. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014, 6, 266ra171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadyr, S.; Adeoye, A.O.; Smatov, S.; Zhakypbekova, A.; Erisken, C. 2023 TERMIS—AMERICAS Conference & Exhibition Boston Marriott Copley Place April 11–14, 2023. Tissue Eng. Part A 2023, 29, 9–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukasheva, F.; Zhanbassynova, A.; Erisken, C. Biomimetic grafts from ultrafine fibers for collagenous tissues. Biomed. Mater. Eng. 2024, 35, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ISO 10993-1:2025; Biological Evaluation of Medical Devices. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025.

| 3D Printing | Casting | Freeze-Drying | Molding | Injection | Electrospinning | Salt Leaching | Implant | Extrusion | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogel | H | L | G | H | L | G | H | L | G | H | L | G | H | L | G | H | L | G | H | L | G | H | L | G | H | L | G |

| Gelatin | 2 [21,60] | 9 [35,36,42,44,47,50,53,56,59] | 6 [32,43,45,51,62,78] | 8 [37,38,39,41,46,49,54,57] | 1 [40] | 1 [61] | 2 [63,64] | 1 [34] | 4 [33,55,58,65] | 1 [48] | |||||||||||||||||

| Alginate | 1 [72] | 1 [68] | 5 [11,20,70,72,77] | 3 [22,66,67] | 1 [76] | 2 [73,74] | 3 [23,69,75] | 1 [24] | 1 [71] | ||||||||||||||||||

| Chitosan | 2 [83,85] | 3 [81,88,89] | 4 [40,84,87,91] | 1 [90] | 2 [80,86] | 3 [27,79,82] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| HA | 2 [96,97] | 3 [95,98,99] | 1 [100] | 1 [94] | 2 [93] | 1 [92] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| OPF | 1 [25] | 2 [113,117] | 1 [116] | 1 [118] | 2 [112,114] | 2 [111,115] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| PEG | 1 [121] | 2 [125,126] | 1 [122] | 1 [120] | 1 [119] | 1 [123] | 1 [124] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| PVA | 2 [109,110] | 1 [102] | 2 [101,106] | 1 [108] | 1 [107] | 2 [103,105] | 1 [104] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Gellan G | 1 [131] | 1 [130] | 1 [129] | 1 [127] | 1 [128] | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| SF | 4 [31,132,133,134] | 1 [135] | 1 [136] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Agarose | 1 [139] | 1 [138] | 1 [137] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| PAMPS PDMA | 2 [140,141] | 1 [142] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Collagen | 1 [144] | 1 [143] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CS | 1 [146] | 1 [145] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| PAAm | 1 [147] | 1 [148] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| PAA | 1 [149] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| PNAGA THMMA | 1 [150] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| PLGA-PBE | 1 [151] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Polyglucosamine | 1 [152] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ELR-based | 1 [153] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| HCF | 1 [154] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Frequency | 6 | 18 | 12 | 7 | 17 | 2 | 12 | 9 | 5 | 8 | 13 | 5 | 9 | 2 | 2 | 3 | - | 1 | - | - | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | 1 |

| % | 4.5 | 13.4 | 9.0 | 5.2 | 12.7 | 1.5 | 9.0 | 6.7 | 3.7 | 6.0 | 9.7 | 3.7 | 6.7 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 2.2 | - | 0.7 | - | - | 0.7 | 0.7 | - | - | - | - | 0.7 |

| Frequency | 36 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 13 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| % | 26.9 | 19.4 | 19.4 | 19.4 | 9.7 | 3.0 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Animal Model | Defect Location | Defect Size (mm) | In Vivo Duration (Weeks) | Outcome Characterization Methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rat | Femoral trochlea; femoral condyle | 2–4 | 6–24 | Histology (H&E, Safranin-O/Fast Green), IHC (COL I, II, X), micro-CT, biomechanical test |

| Rabbit | Medial femoral condyle; trochlear groove | 2–6 | 4–24 | Histology, IHC (COL II, aggrecan), macroscopic scoring, micro-CT |

| Pig/Minipig | Femoral condyle; trochlea | 4–8.5 | 16–24 | Histology, IHC, micro-CT, MRI, biomechanical test |

| Horse | Femoral condyle | 10 | 26–48 | Histology, IHC, micro-CT, MRI, biomechanical test |

| Dog | Femoral condyle | 6 | 12 | Histology, IHC, imaging, biomechanical test |

| Sheep | Femoral condyle | 8 | 16 | Histology, IHC, micro-CT, biomechanical test |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kadyr, S.; Khumyrzakh, B.; Naz, S.; Abdossova, A.; Askarbek, B.; Kalyon, D.M.; Liu, Z.; Erisken, C. Hydrogels for Osteochondral Interface Regeneration: Biomaterial Types, Processes, and Animal Models. Gels 2026, 12, 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010024

Kadyr S, Khumyrzakh B, Naz S, Abdossova A, Askarbek B, Kalyon DM, Liu Z, Erisken C. Hydrogels for Osteochondral Interface Regeneration: Biomaterial Types, Processes, and Animal Models. Gels. 2026; 12(1):24. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010024

Chicago/Turabian StyleKadyr, Sanazar, Bakhytbol Khumyrzakh, Swera Naz, Albina Abdossova, Bota Askarbek, Dilhan M. Kalyon, Zhe Liu, and Cevat Erisken. 2026. "Hydrogels for Osteochondral Interface Regeneration: Biomaterial Types, Processes, and Animal Models" Gels 12, no. 1: 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010024

APA StyleKadyr, S., Khumyrzakh, B., Naz, S., Abdossova, A., Askarbek, B., Kalyon, D. M., Liu, Z., & Erisken, C. (2026). Hydrogels for Osteochondral Interface Regeneration: Biomaterial Types, Processes, and Animal Models. Gels, 12(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010024