Camellia Oil Oleogels Structured with Walnut Protein–Chitosan Complexes: Preparation, Characterization, and Potential Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Analysis of WCCEs

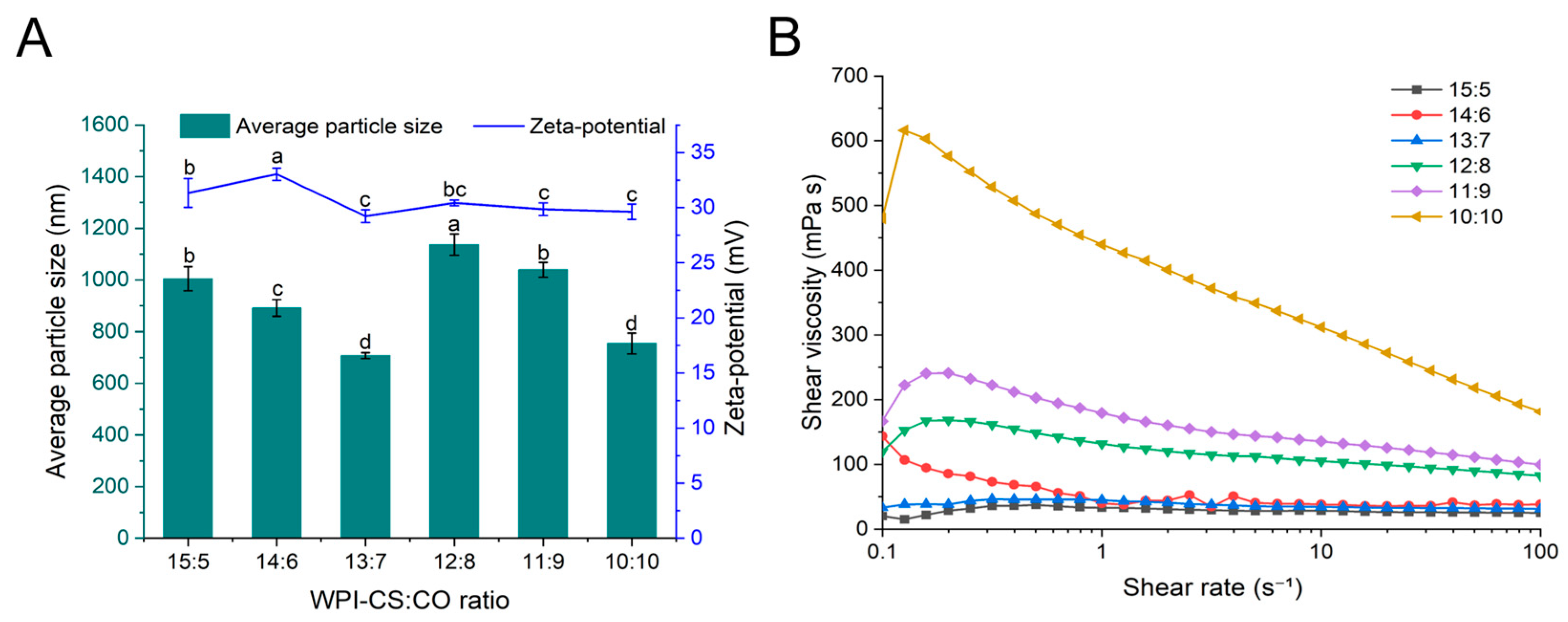

2.1.1. Mean Particle Size, Zeta Potential, and Viscosity

2.1.2. Morphology of WCCEs

2.2. Analysis of Freeze-Dried Samples

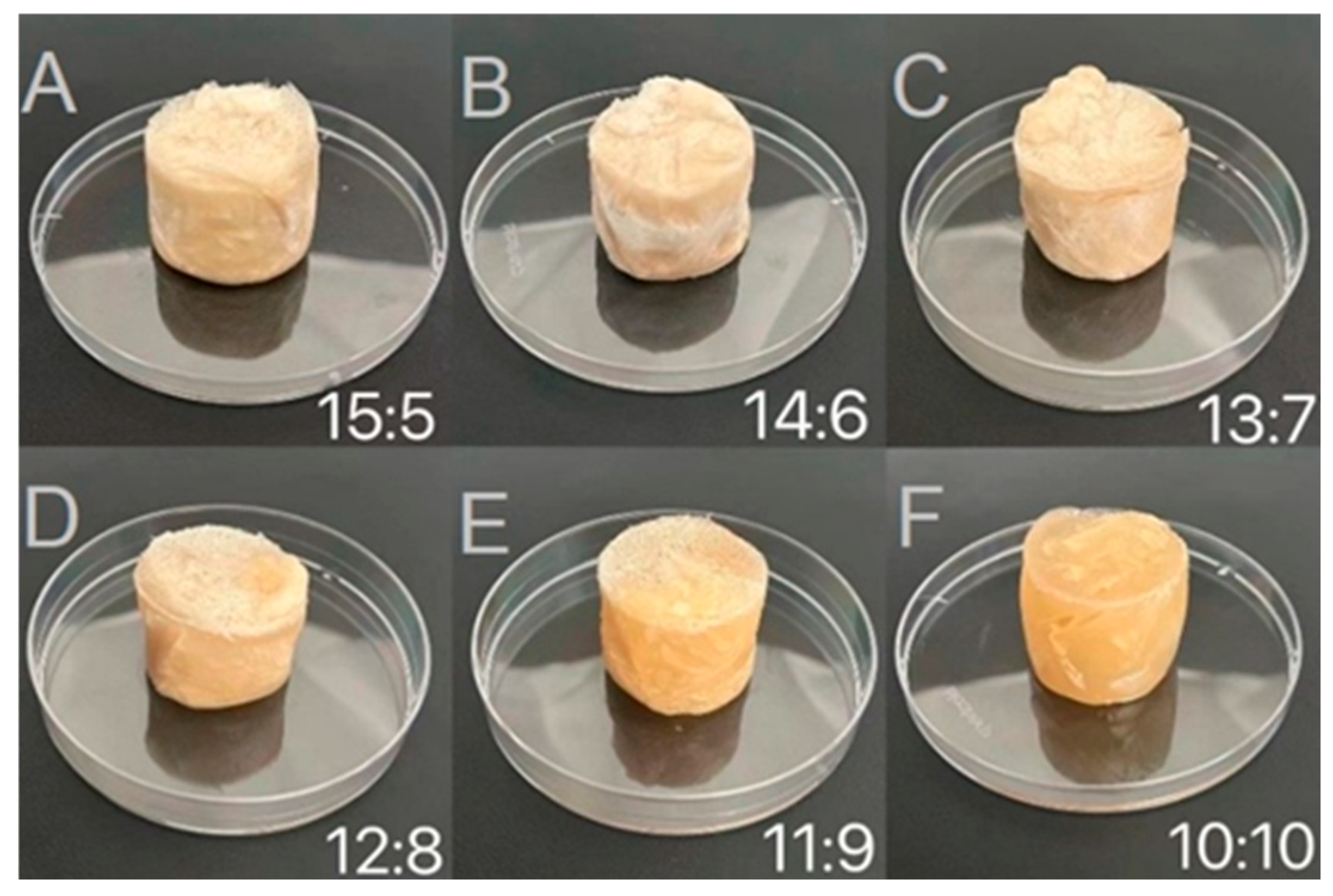

2.2.1. Visual Appearance of Freeze-Dried Samples

2.2.2. TPA of Freeze-Dried Samples

2.3. Analysis of WCCO Oleogels

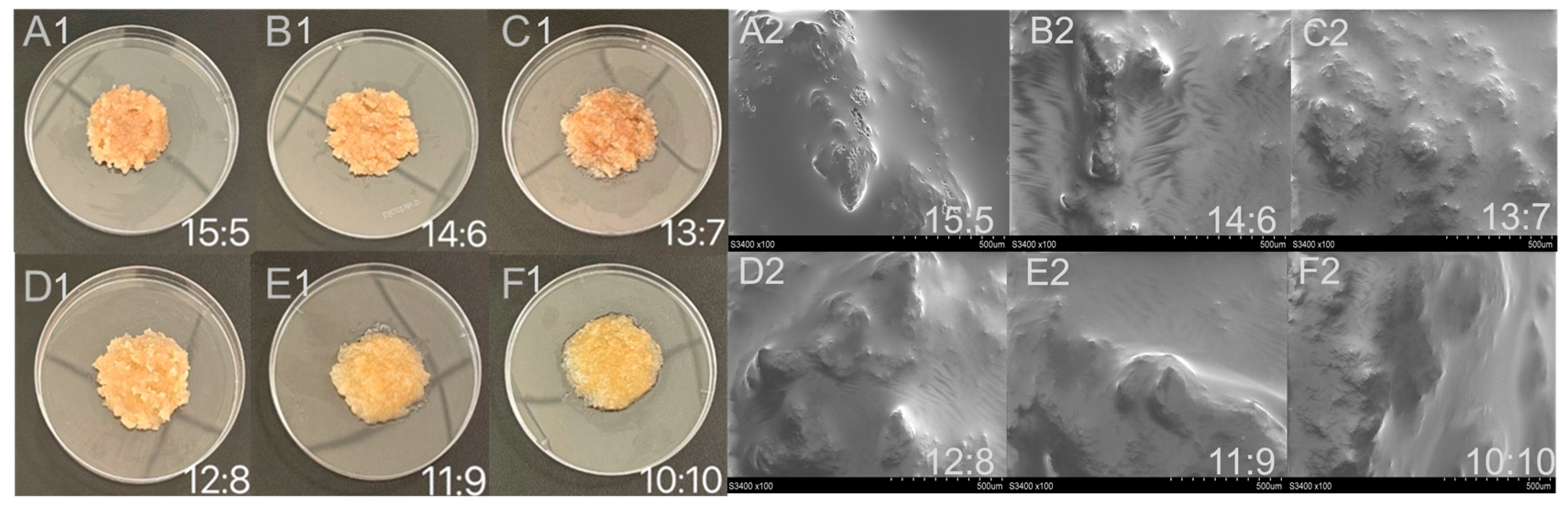

2.3.1. Morphology of WCCO

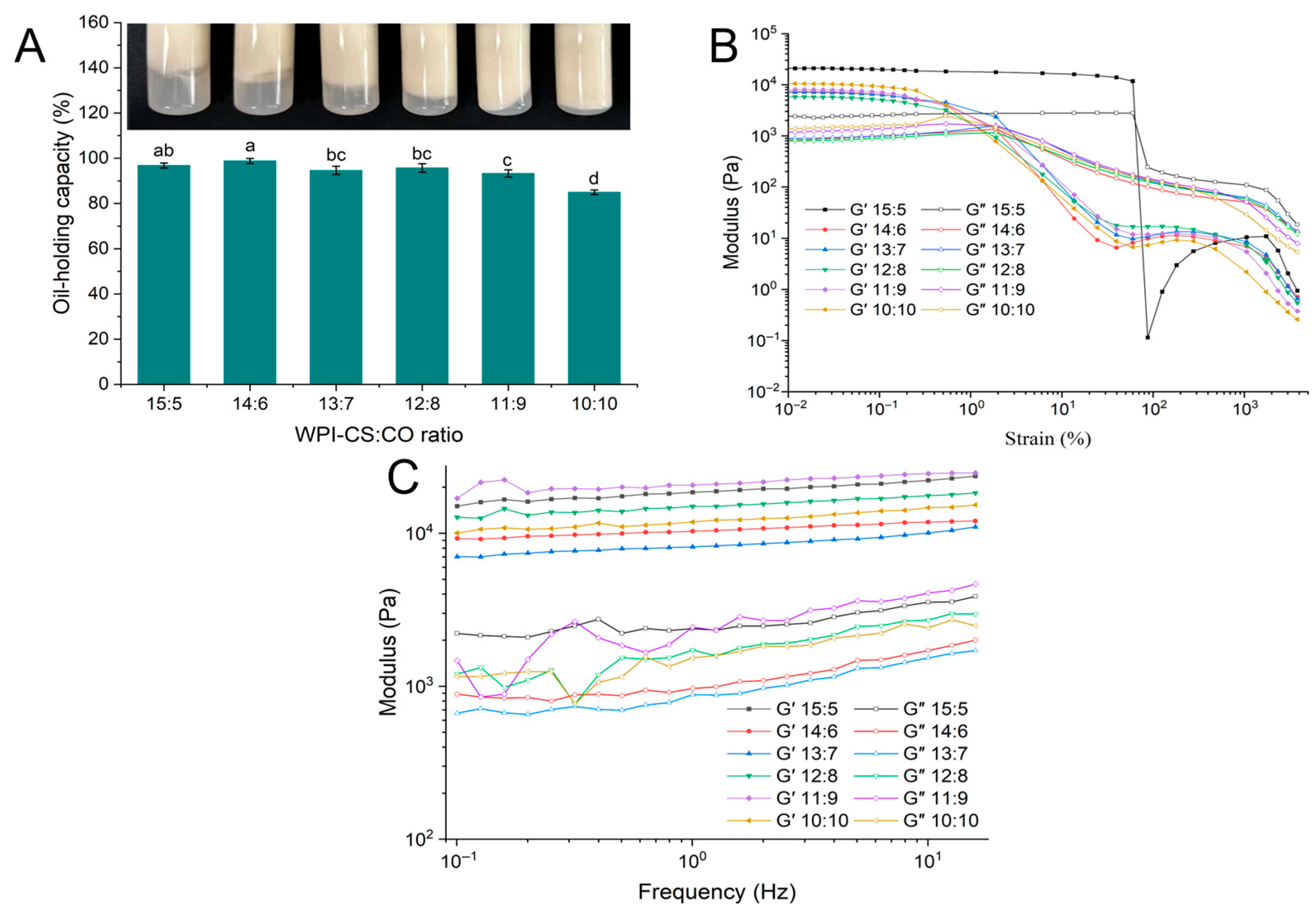

2.3.2. OHC of WCCO Oleogels

2.3.3. Rheological Properties of WCCO Oleogels

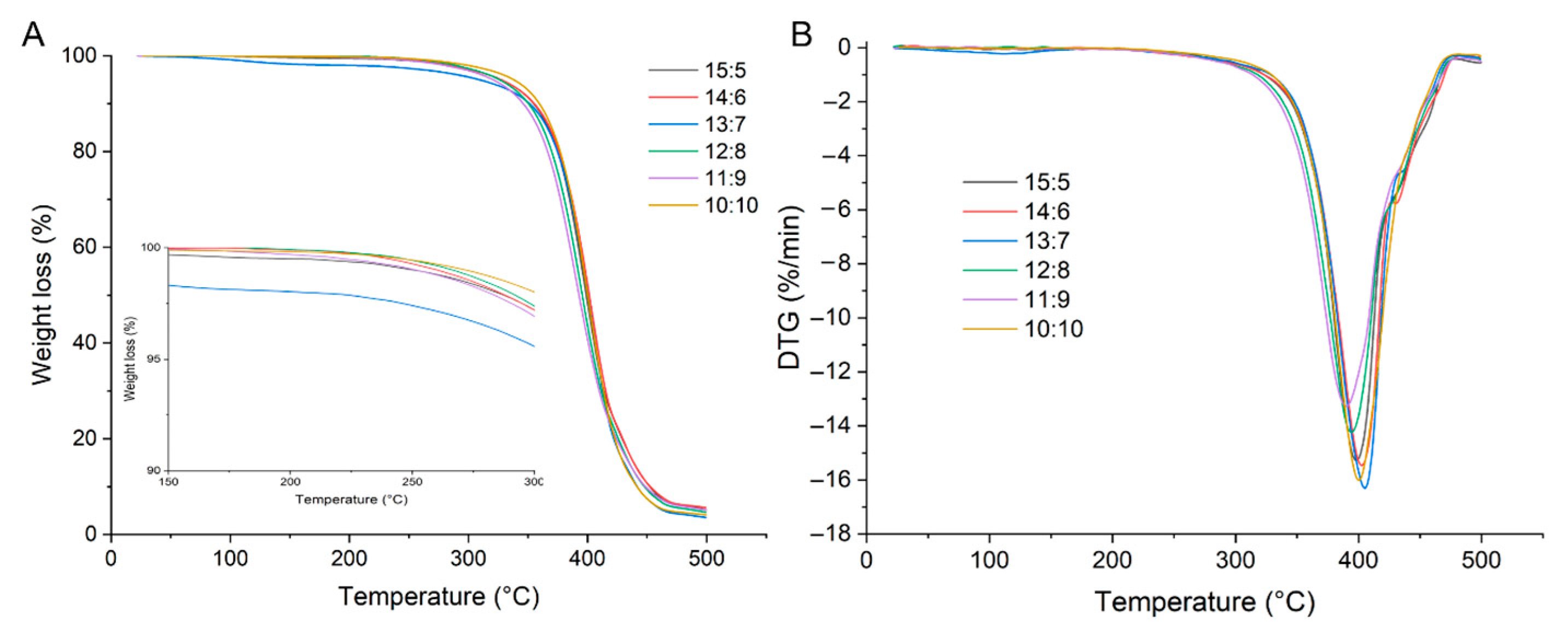

2.3.4. Thermal Stability of WCCO Oleogels

2.4. Microstructure of Cake Batters

2.5. Textural Analysis and Sensory Evaluation of Cakes

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Extraction of WPI

4.3. Preparation of WCCEs, Freeze-Dried Samples, and Oleogels

4.4. Characterization of WCCEs

4.4.1. Mean Particle Size and Zeta Potential Measurements

4.4.2. Viscosity Measurement

4.4.3. Morphological Observation

4.5. Characterization of Freeze-Dried Samples

4.5.1. Visual Appearance Analysis

4.5.2. Textural Analysis

4.6. Characterization of Oleogels

4.6.1. Morphological Observation

4.6.2. OHC Measurement

4.6.3. Rheological Property Measurement

4.6.4. Thermal Stability Measurement

4.7. Cake Preparation and Characterization

4.7.1. Cake Preparation

4.7.2. Microstructure of Cake Batter

4.7.3. TPA of Cakes

4.7.4. Sensory Evaluation of Cakes

4.8. Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, Q.; Rao, Z.; Jiang, L.; Lei, X.; Zhao, J.; Lei, L.; Zeng, K.; Ming, J. Oleogels loaded with lycopene structured using Zein/EGCG/Ca2+ complexes: Preparation, characterization and potential application. Food Chem. 2025, 463, 140976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Cui, J.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, J.; Chen, X.; Shan, K. Advancements in extraction asnd sustainable applications of Camellia oleifera: A comprehensive review. Food Chem. 2025, 488, 144940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Cai, Y.; Chen, K.; You, R.; Lu, Y. Camellia oleifera oil: Unveiling health benefits and exploring novel applications. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 66, 108–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Jin, L.; Liu, Q.; Zhao, K.; Lin, L.; Zheng, J.; Li, C.; Chen, B.; Shen, Y. Recent advances in the extraction, composition analysis and bioactivity of Camellia (Camellia oleifera Abel.) oil. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 143, 104211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Ding, J.; Li, Y.; Wei, P.; Liu, S.; Yang, R. The Formation of Protein–Chitosan Complexes: Their Interaction, Applications, and Challenges. Foods 2024, 13, 3572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Can Karaca, A.; Assadpour, E.; Jafari, S.M. Plant protein-based emulsions for the delivery of bioactive compounds. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 316, 102918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zambrano, J.C.; Vilgis, T.A. Tunable oleosome-based oleogels: Influence of polysaccharide type for polymer bridging-based structuring. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 137, 108399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Liu, L.; Li, X.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Z.; Chen, N.; Wang, H.; Xie, F.; Qi, B.; Jiang, L. Construction of soybean oil bodies-xanthan gum composite oleogels by emulsion-templated method: Preparation, characterization, and stability analysis. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 149, 109526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, W.; Sun, H.; Mu, T.; Garcia-Vaquero, M. Chitosan-based Pickering emulsion: A comprehensive review on their stabilizers, bioavailability, applications and regulations. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 304, 120491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harugade, A.; Sherje, A.P.; Pethe, A. Chitosan: A review on properties, biological activities and recent progress in biomedical applications. React. Funct. Polym. 2023, 191, 105634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Huang, C.; Zheng, C.; Wang, W.; Ying, H.; Liu, C. Effect of oil extraction methods on walnut oil quality characteristics and the functional properties of walnut protein isolate. Food Chem. 2024, 438, 138052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Zhu, W.; Yi, J.; Liu, N.; Cao, Y.; Lu, J.; Decker, E.A.; McClements, D.J. Effects of sonication on the physicochemical and functional properties of walnut protein isolate. Food Res. Int. 2018, 106, 853–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, M.; Xu, Y.; Xu, L.; Chen, X.; Ding, M.; Bai, Y.; Xu, X.; Zeng, X. The evaluation of mixed-layer emulsions stabilized by myofibrillar protein-chitosan complex for delivering astaxanthin: Fabrication, characterization, stability and in vitro digestibility. Food Chem. 2024, 440, 138204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Gao, N.; Wang, X.; Sun, S. Multivariable analysis of egg white protein-chitosan interaction: Influence of pH, temperature, biopolymers ratio, and ionic concentration. Food Chem. X 2023, 19, 100817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, S.-Z.; Hu, X.-F.; Jia, Y.-J.; Pan, L.-H.; Zheng, Z.; Zhao, Y.-Y.; Mu, D.-D.; Zhong, X.-Y.; Jiang, S.-T. Camellia oil-based oleogels structuring with tea polyphenol-palmitate particles and citrus pectin by emulsion-templated method: Preparation, characterization and potential application. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 95, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakansamut, N.; Adulpadungsak, K.; Sonwai, S.; Aryusuk, K.; Lilitchan, S. Application of functional oil blend-based oleogels as novel structured oil alternatives in chocolate spread. LWT 2024, 203, 116322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Liu, G.; Bogojevic, O.; Pedersen, J.N.; Guo, Z. Edible oleogels as solid fat alternatives: Composition and oleogelation mechanism implications. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2022, 21, 2077–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.-Z.; Hu, X.-F.; Pan, L.-H.; Zheng, Z.; Zhao, Y.-Y.; Cao, L.-L.; Pang, M.; Hou, Z.-G.; Jiang, S.-T. Preparation of camellia oil-based W/O emulsions stabilized by tea polyphenol palmitate: Structuring camellia oil as a potential solid fat replacer. Food Chem. 2019, 276, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günal-Köroğlu, D.; Gultekin Subasi, B.; Saricaoglu, B.; Karabulut, G.; Capanoglu, E. Exploring the frontier of bioactive oleogels in recent research. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 151, 104613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, A.J.; Vicente, A.A.; Cunha, R.L.; Cerqueira, M.A. Edible oleogels: An opportunity for fat replacement in foods. Food Funct. 2018, 9, 758–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavya, M.; Udayarajan, C.; Fabra, M.J.; López-Rubio, A.; Nisha, P. Edible oleogels based on high molecular weight oleogelators and its prospects in food applications. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 4432–4455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Jin, L.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, H.; Lin, L.; Li, C.; Chen, B.; Shen, Y. Fabrication of novel polysaccharides and glycerol monolaurate based camellia oil composite oleogel: Application in wound healing promotion. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 281, 136239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, W.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, Q.; McClements, D.J.; Ji, H.; Jiang, L.; Wen, J.; Jin, Z.; Qiu, C. Preparation of emulsion-template oleogels: Tuning properties by controlling initial water content and evaporation method. Food Hydrocoll. 2025, 158, 110519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Elsoud, M.; Salama, M.; Li, Z.; Wang, S.; Cai, Z.; Ahn, D.U.; Huang, X. Structuring low-density lipoprotein-based oleogels with pectin via an emulsion-templated approach: Formation and characterization. J. Food Eng. 2025, 387, 112340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Zhang, W.; Liu, R.; Chang, C.; Li, J.; Xiong, W.; Yang, Y.; Gu, L. Emulsion-Templated Liquid Oil Structuring with Egg White Protein Microgel- Xanthan Gum. Foods 2023, 12, 1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Champrasert, O.; Sagis, L.M.C.; Suwannaporn, P. Emulsion-based oleogelation using octenyl succinic anhydride modified granular cold-water swelling starch. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 135, 108186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijarnprecha, K.; Aryusuk, K.; Santiwattana, P.; Sonwai, S.; Rousseau, D. Structure and rheology of oleogels made from rice bran wax and rice bran oil. Food Res. Int. 2018, 112, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Qin, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, G.; Cheng, G.; Soteyome, T. Controlling release of astaxanthin in β-sitosterol oleogel-based emulsions via different self-assembled mechanisms and composition of the oleogelators. Food Res. Int. 2024, 186, 114350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, S.; Ahmad, M.I.; Ali, U.; Zhang, H. Fabrication of curcumin-loaded oleogels using camellia oil bodies and gum arabic/chitosan coatings for controlled release applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 254, 127758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Zhao, S.; Zhu, Q.; Zhang, H. Characterization of chitosan-gelatin cryogel templates developed by chemical crosslinking and oxidation resistance of camellia oil cryogel-templated oleogels. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 315, 120971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Hu, L.; Xiao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, S.; Zheng, M.; Yu, Z.; Liu, K.; Zhou, Y. Gel Properties and Formation Mechanism of Camellia Oil Body-Based Oleogel Improved by Camellia Saponin. Gels 2022, 8, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, X.; Chen, Z.; Tang, Z.; Tao, Y.; Huang, Q.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, X.; Liang, J.; Liu, Z.; et al. Preparation of camellia oil oleogel and its application in an ice cream system. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 169, 113985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravera, F.; Dziza, K.; Santini, E.; Cristofolini, L.; Liggieri, L. Emulsification and emulsion stability: The role of the interfacial properties. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 288, 102344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejía-Méndez, J.L.; Vazquez-Duhalt, R.; Hernández, L.R.; Sánchez-Arreola, E.; Bach, H. Virus-like Particles: Fundamentals and Biomedical Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, D.; Kelly, A.L.; Maidannyk, V.; Miao, S. Effect of structuring emulsion gels by whey or soy protein isolate on the structure, mechanical properties, and in-vitro digestion of alginate-based emulsion gel beads. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 110, 106165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcclements, D.J. Food Emulsions: Principles, Practices, and Techniques, 3rd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, Z.; Qi, K.; Guo, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y. Macro-micro structure characterization and molecular properties of emulsion-templated polysaccharide oleogels. Food Hydrocoll. 2018, 77, 17–29. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, X.; Hu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Jiang, K.; Liang, Y.; Li, J.; Guo, X.; Zhu, B. Marine sulfated polysaccharide affects the characteristics of astaxanthin-loaded oleogels prepared from gelatin emulsions. Food Hydrocoll. 2025, 160, 110805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.; Yang, X.; Wang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Pan, J.; Sun, Q.; Dong, X. Konjac glucomannan-assisted fabrication of stable emulsion-based oleogels constructed with pea protein isolate and its application in surimi gels. Food Chem. 2024, 443, 138538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Z.; Bai, X. Effects of Polysaccharide Concentrations on the Formation and Physical Properties of Emulsion-Templated Oleogels. Molecules 2022, 27, 5391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Li, P.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Jiang, J.; Cheng, X.; Bi, L. Camellia Saponin Based Oleogels by Emulsion-Templated Method: Preparation, Characterization, and in Vitro Digestion. ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 3, 2085–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xi, Y.; Wu, L.; Zhang, H. Preparation, characterization and in vitro digestion of bamboo shoot protein/soybean protein isolate based-oleogels by emulsion-templated approach. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 136, 108310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.R.; Rajarethinem, P.S.; Grędowska, A.; Turhan, O.; Lesaffer, A.; De Vos, W.H.; Van de Walle, D.; Dewettinck, K. Edible applications of shellac oleogels: Spreads, chocolate paste and cakes. Food Funct. 2014, 5, 645–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.R.; Cludts, N.; Sintang, M.D.B.; Lesaffer, A.; Dewettinck, K. Edible oleogels based on water soluble food polymers: Preparation, characterization and potential application. Food Funct. 2014, 5, 2833–2841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavernier, I.; Patel, A.R.; Van der Meeren, P.; Dewettinck, K. Emulsion-templated liquid oil structuring with soy protein and soy protein: κ-carrageenan complexes. Food Hydrocoll. 2017, 65, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| WPI-CS:CO | Hardness (g) | Springiness (mm) | Cohesiveness (−) | Gumminess (g) | Chewiness (mJ) | Resilience (−) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15:5 | 170.19 ± 81.55 a | 0.44 ± 0.01 a | 0.41 ± 0.02 abc | 69.81 ± 8.02 c | 30.52 ± 5.01 c | 0.14 ± 0.02 ab |

| 14:6 | 182.9 ± 29.81 a | 0.41 ± 0.03 a | 0.44 ± 0.03 abc | 87.55 ± 1.31 b | 35.90 ± 0.09 c | 0.14 ± 0.02 ab |

| 13:7 | 172.9 ± 28.78 a | 0.42 ± 0.02 a | 0.37 ± 0.01 c | 104.00 ± 2.02 a | 43.08 ± 1.93 b | 0.13 ± 0.01 b |

| 12:8 | 94.01 ± 24.57 b | 0.45 ± 0.07 a | 0.40 ± 0.02 bc | 111.30 ± 5.89 a | 48.79 ± 0.08 a | 0.12 ± 0.01 b |

| 11:9 | 49.48 ± 20.04 b | 0.50 ± 0.02 a | 0.41 ± 0.03 abc | 81.69 ± 10.56 bc | 38.79 ± 7.49 bc | 0.16 ± 0.01 a |

| 10:10 | 36.24 ± 14.1 b | 0.49 ± 0.05 a | 0.46 ± 0.04 a | 78.13 ± 2.53 c | 42.84 ± 2.15 b | 0.14 ± 0.01 ab |

| Sample | Hardness (g) | Springiness (mm) | Adhesiveness (mJ) | Cohesiveness (−) | Chewiness (mJ) | Resilience (−) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Butter | 458.36 ± 206.03 c | 0.89 ± 0.12 a | 0.80 ± 0.22 a | 356.16 ± 160.13 c | 322.69 ± 163.74 c | 0.32 ± 0.45 a |

| WPI-CS:CO (15:5) | 2732.06 ± 534.09 a | 0.82 ± 0.01 a | 0.41 ± 0.13 b | 1129.16 ± 233.24 a | 924.43 ± 193.95 a | 0.15 ± 0.01 a |

| WPI-CS:CO (13:7) | 1630.14 ± 357.03 b | 0.86 ± 0.07 a | 0.53 ± 0.23 b | 805.40 ± 118.35 b | 698.00 ± 145.82 b | 0.15 ± 0.07 a |

| WPI-CS:CO (11:9) | 1211.66 ± 212.06 b | 0.93 ± 0.21 a | 0.52 ± 0.05 b | 626.91 ± 114.92 b | 587.25 ± 180.61 b | 0.22 ± 0.03 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

An, J.; Zheng, L.; Xuan, S.; He, X.; Yang, T. Camellia Oil Oleogels Structured with Walnut Protein–Chitosan Complexes: Preparation, Characterization, and Potential Applications. Gels 2026, 12, 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010020

An J, Zheng L, Xuan S, He X, Yang T. Camellia Oil Oleogels Structured with Walnut Protein–Chitosan Complexes: Preparation, Characterization, and Potential Applications. Gels. 2026; 12(1):20. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010020

Chicago/Turabian StyleAn, Jun, Liyou Zheng, Shuzhen Xuan, Xinyi He, and Tao Yang. 2026. "Camellia Oil Oleogels Structured with Walnut Protein–Chitosan Complexes: Preparation, Characterization, and Potential Applications" Gels 12, no. 1: 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010020

APA StyleAn, J., Zheng, L., Xuan, S., He, X., & Yang, T. (2026). Camellia Oil Oleogels Structured with Walnut Protein–Chitosan Complexes: Preparation, Characterization, and Potential Applications. Gels, 12(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010020