Diversity of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi in Rhizosphere Soil of Maize in Northern Xinjiang, China, and Evaluation of Inoculation Benefits of Three Strains

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

2.2. Soil DNA Extraction and High-Throughput Sequencing

2.3. Root Colonization and Spore Isolation and Identification of AMF

2.4. Determination of the Soil’s Physical and Chemical Properties and Enzyme Activity

2.5. Single Spore Propagation and Identification

2.6. Potted Maize Growth-Promoting Experiment

2.7. Data Processing

3. Results

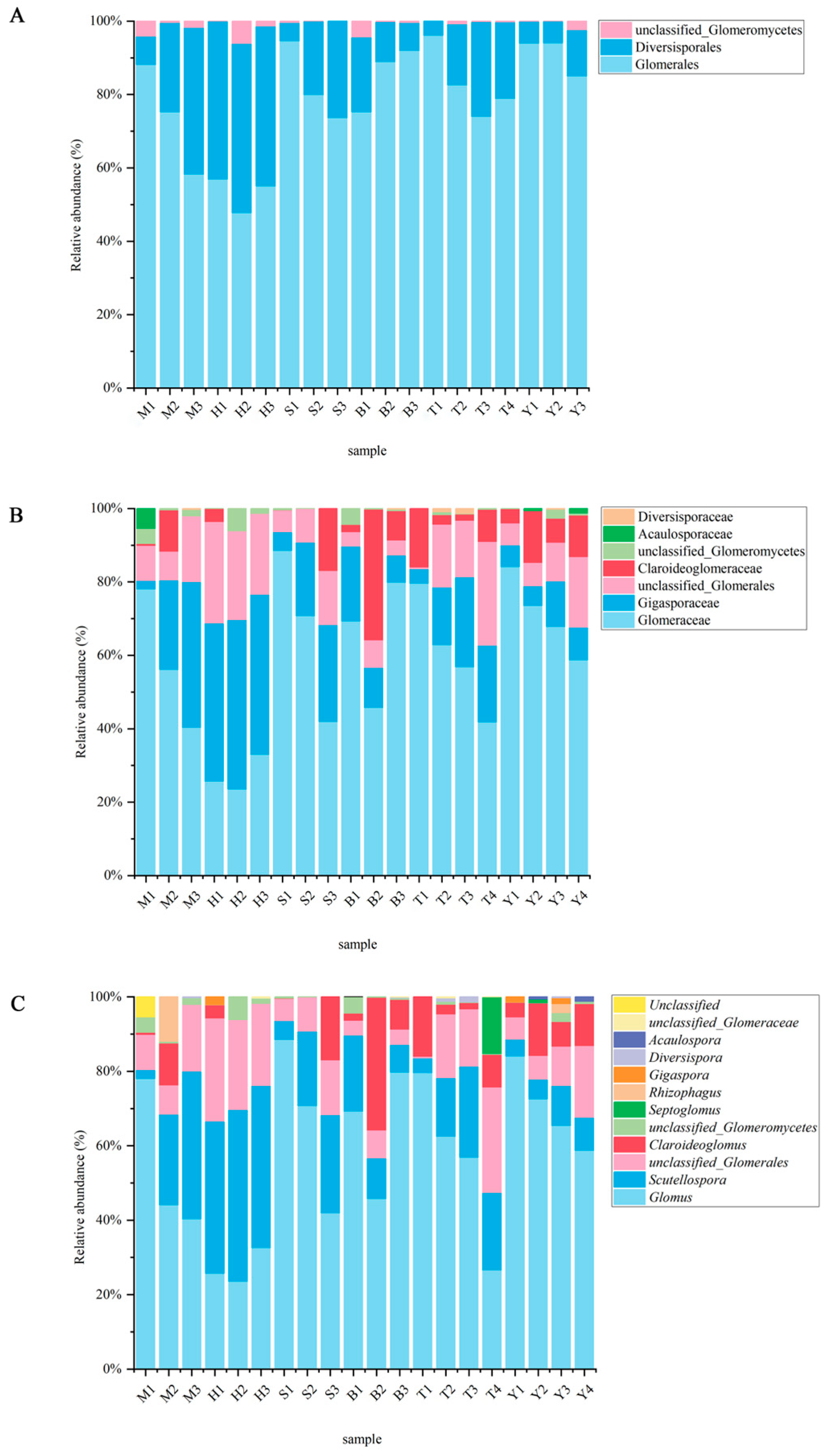

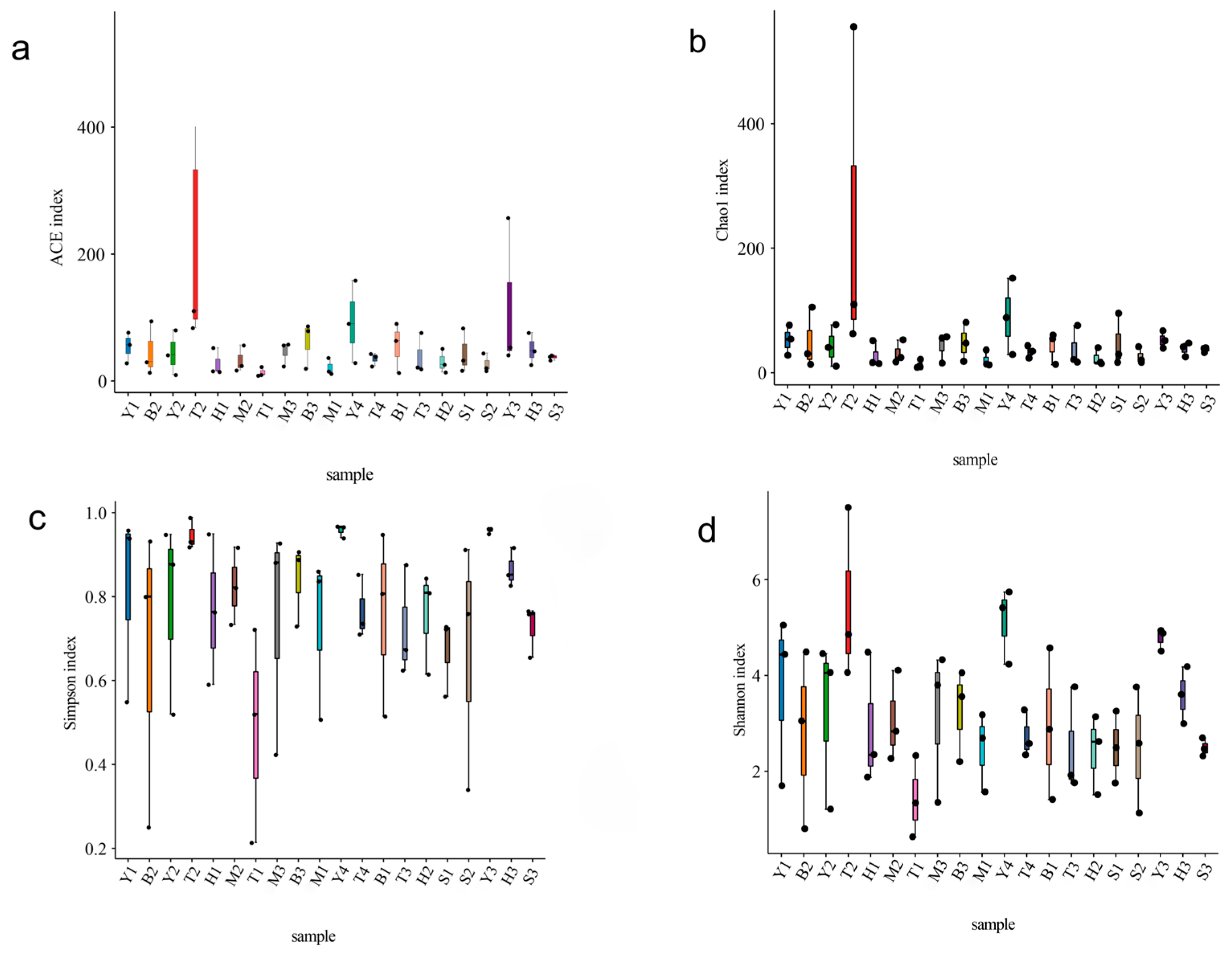

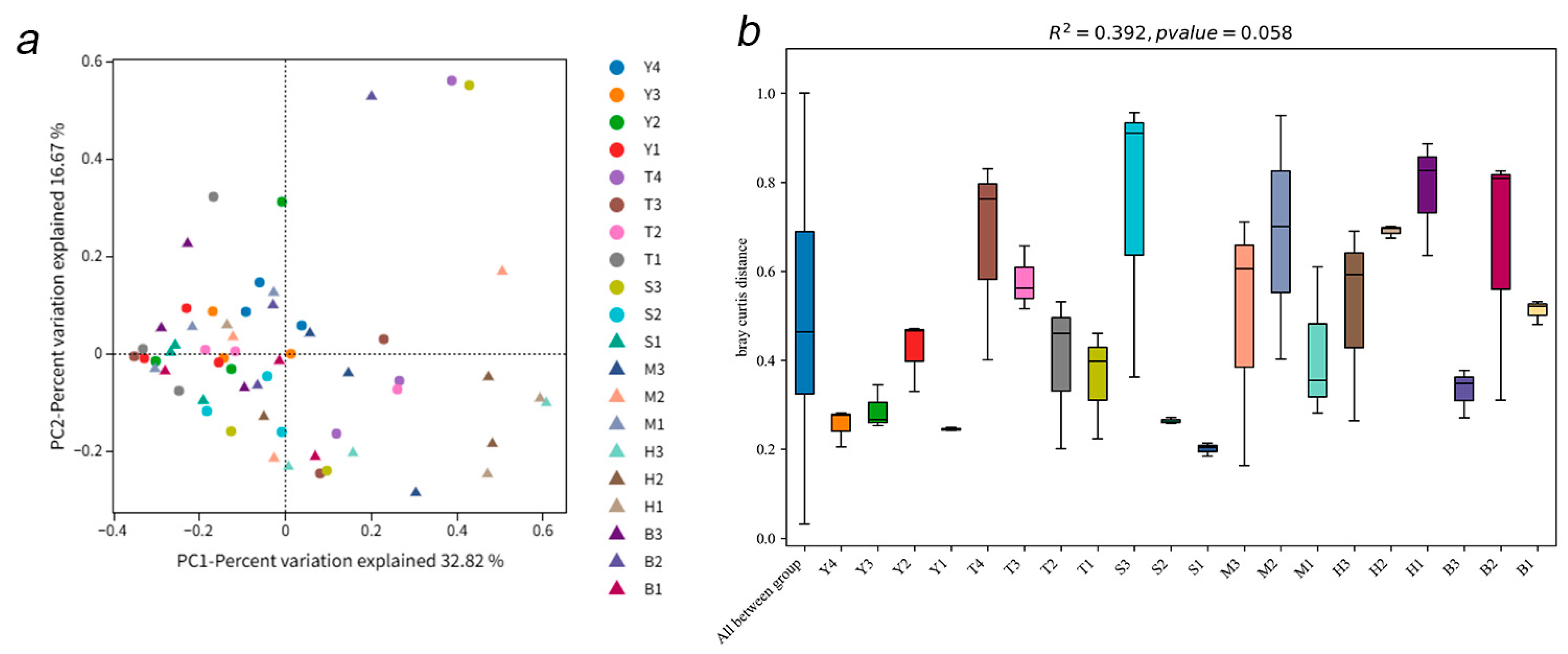

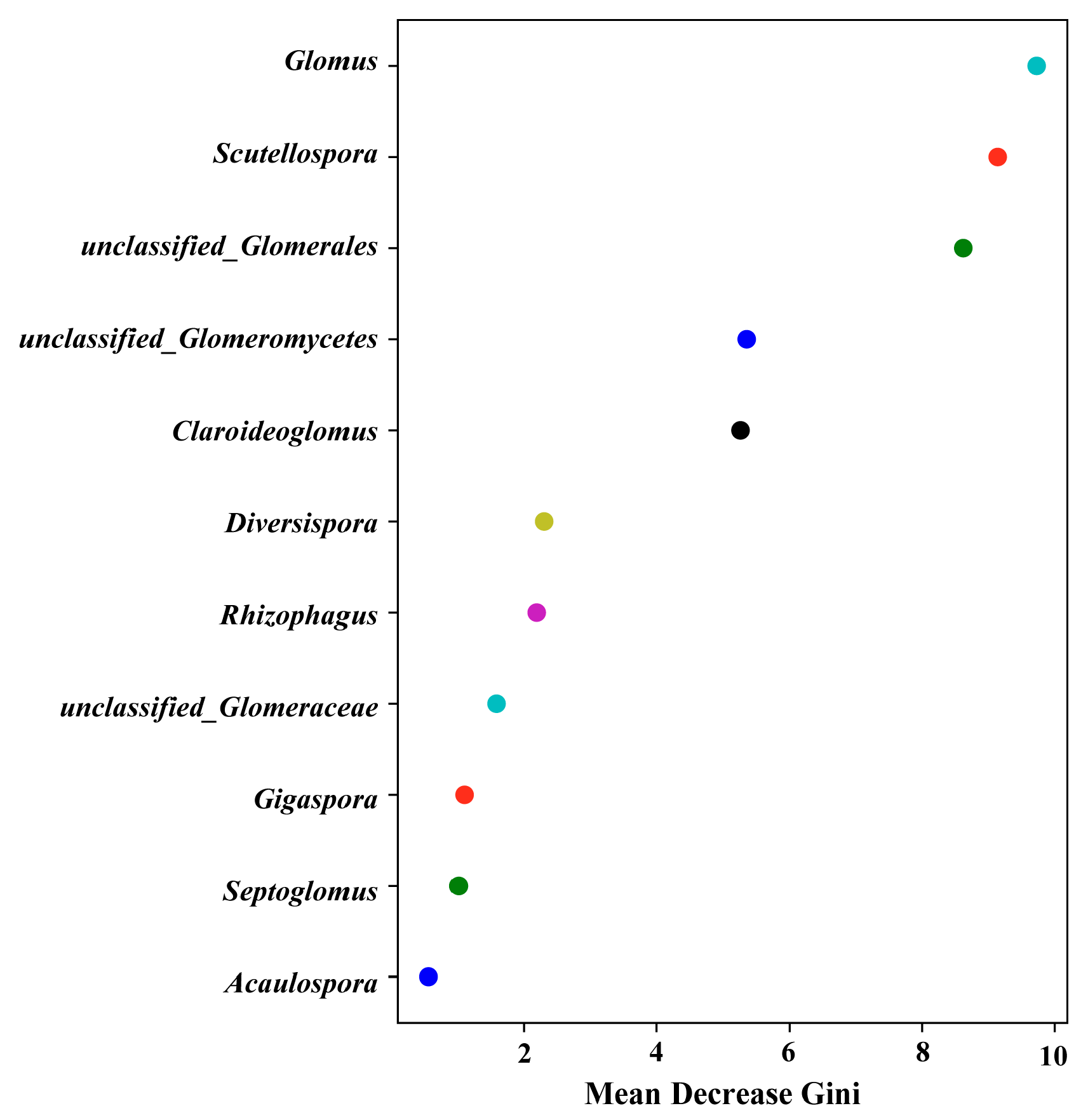

3.1. AMF Community Composition and Diversity

3.2. Relationship Between AMF Diversity and Soil Properties

3.3. Isolation, Identification and Colonization of Maize Rhizosphere AMF

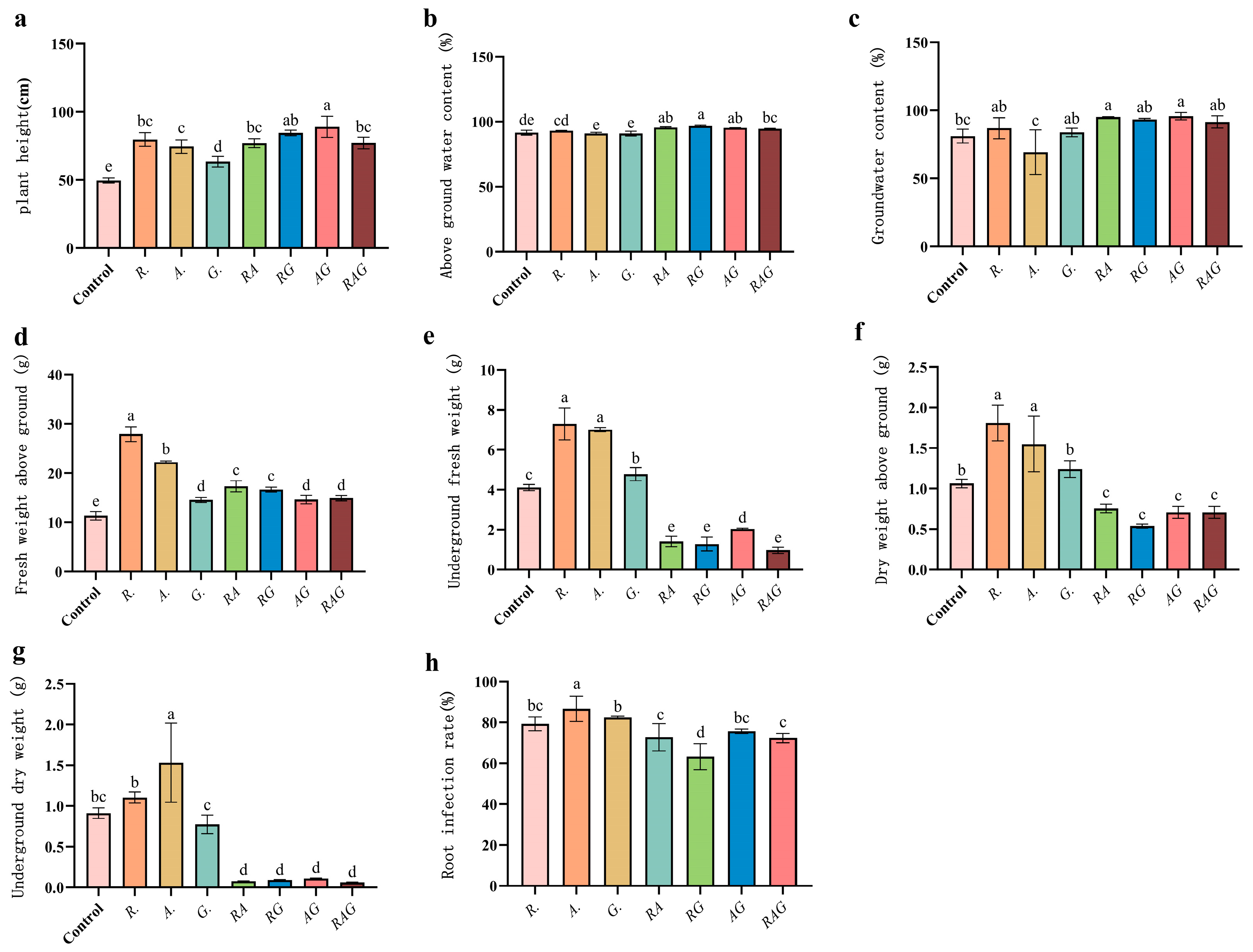

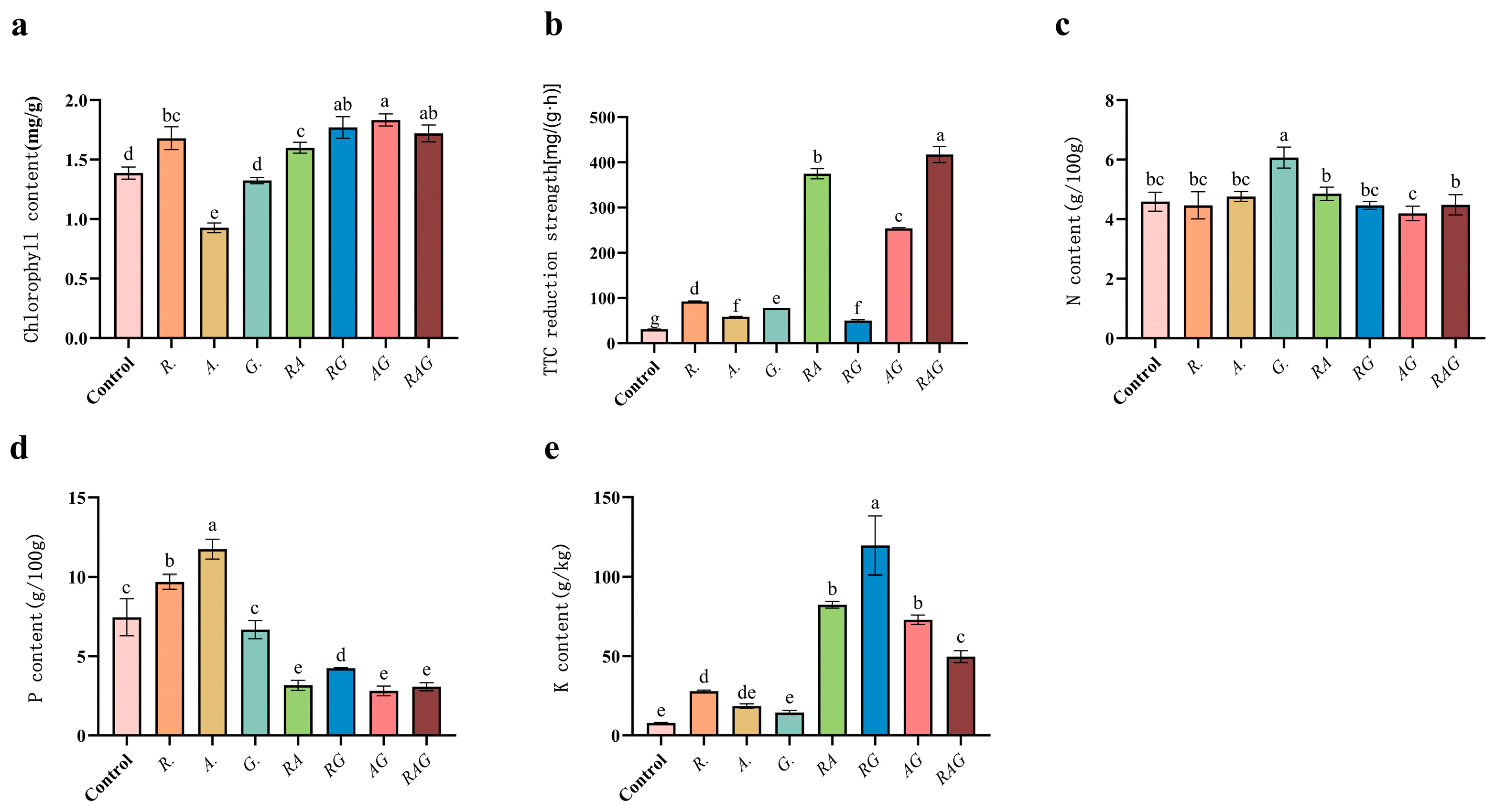

3.4. Inoculating AMF to Promote the Growth of Maize Seedlings

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMF | Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi |

| ASVs | Amplicon sequence variants |

| RDA | Redundancy Analysis |

| TK | Total Potassium |

| TN | Total Nitrogen |

| TP | Total Phosphorus |

| AK | Available Potassium |

| AN | Available Nitrogen |

| AP | Available Phosphorus |

| SOM | Soil Organic Matter |

| EC | Electrical Conductivity |

| PRO | Protein |

| SUR | Sucrase |

| S_ACP | Soil Acid Phosphatase |

| R. | Rhizophagus intraradices |

| A. | Acaulospora denticulata |

| G. | Glomus melanosporum |

| RA | Rhizophagus intraradices * Acaulospora denticulata |

| RG | Rhizophagus intraradices * Glomus melanosporum |

| AG | Acaulospora denticulata * Glomus melanosporum |

| HTS | High-throughput sequencing |

References

- Sharma, K.; Singh, M.; Srivastava, D.K.; Singh, P.K. Advances and Current Perspectives on Root Organ Culture of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi. J. Adv. Biol. Biotechnol. 2025, 28, 120–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parniske, M. Arbuscular mycorrhiza: The mother of plant root endosymbioses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2008, 6, 763–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-L.; Xu, Z.-W.; Xu, T.-L.; Veresoglou, S.D.; Yang, G.-W.; Chen, B.-D. Nitrogen deposition and precipitation induced phylogenetic clustering of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal communities. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2017, 115, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhlanga, B.; Ercoli, L.; Piazza, G.; Thierfelder, C.; Pellegrino, E. Occurrence and diversity of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi colonising off-season and in-season weeds and their relationship with maize yield under conservation agriculture. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2022, 58, 917–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Shi, Z.; Yang, M.; Lu, S.; Cao, L.; Wang, X. Molecular Diversity and Distribution of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi at Different Elevations in Mt. Taibai of Qinling Mountain. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 609386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Shi, Z.; Wang, F. Co-occurring tree species drive arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi diversity in tropical forest. Int. Microbiol. 2024, 27, 917–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.; Vandenkoornhuyse, P.J.; Leake, J.R.; Gilbert, L.; Booth, R.E.; Grime, J.P. Plant communities affect arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal diversity and community composition in grassland microcosms. New Phytol. 2004, 161, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dassen, S.; Cortois, R.; Martens, H.; de Hollander, M.; Kowalchuk, G.A.; van der Putten, W.H. Differential responses of soil bacteria, fungi, archaea and protists to plant species richness and plant functional group identity. Mol. Ecol. 2017, 26, 4085–4098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liang, Z.; Zheng, L.; Wang, X.; Chen, H.; Xu, T. Impact of long-term loquat cultivation on rhizosphere soil characteristics and AMF community structure: Implications for fertilizer management. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1549384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoninka, A.; Reich, P.B.; Johnson, N.C. Seven years of carbon dioxide enrichment, nitrogen fertilization and plant diversity influence arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in a grassland ecosystem. New Phytol. 2011, 192, 200–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Loeppmann, S.; Yang, H.; Gube, M.; Shi, L.; Pausch, J. Linking microbial community dynamics to rhizosphere carbon flow depend on arbuscular mycorrhizae and nitrogen fertilization. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2025, 61, 791–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alguacil, M.M.; Torrecillas, E.; Roldán, A.; Díaz, G.; Torres, M.P. Perennial plant species from semiarid gypsum soils support higher AMF diversity in roots than the annual Bromus rubens. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2012, 49, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; He, X.; Chen, C.; Feng, S.; Liu, L.; Chen, X. Influence of plant communities and soil properties during natural vegetation restoration on arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal communities in a karst region. Ecol. Eng. 2015, 82, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rillig, M.C.; Mummey, D.L. Mycorrhizas and soil structure. New Phytol. 2006, 171, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Chen, K.; He, D.; He, Y.; Lei, Y.; Sun, Y. A Review on Rhizosphere Microbiota of Tea Plant (Camellia sinensis L): Recent Insights and Future Perspectives. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 19165–19188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Xiang, X.; Yang, T.; Liu, X.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, K.; Liu, X.; Chu, H. Nitrogen fertilization reduces plant diversity by changing the diversity and stability of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal community in a temperate steppe. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 918, 170775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianinazzi, S.; Gollotte, A.; Binet, M.N.; van Tuinen, D.; Redecker, D.; Wipf, D. Agroecology: The key role of arbuscular mycorrhizas in ecosystem services. Mycorrhiza 2010, 20, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Zhao, Y. Phytoplasma Taxonomy: Nomenclature, Classification, and Identification. Biology 2022, 11, 1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkoris, V.; Banchini, C.; Paré, L.; Abdellatif, L.; Séguin, S.; Hubbard, K.; Findlay, W.; Dalpé, Y.; Dettman, J.; Corradi, N.; et al. Rhizophagus irregularis, the model fungus in arbuscular mycorrhiza research, forms dimorphic spores. New Phytol. 2024, 242, 1771–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, N.; Li, D.; Yang, R. Next-generation sequencing technologies and the application in microbiology—A review. Wei Sheng Wu Xue Bao 2011, 51, 445–457. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Z.L.; Yang, M.K.; Fazal, A.; Han, H.W.; Lin, H.Y.; Yin, T.M.; Zhu, Y.L.; Yang, S.P.; Niu, K.C.; Sun, S.C.; et al. Harnessing the power of microbes: Enhancing soybean growth in an acidic soil through AMF inoculation rather than P-fertilization. Hortic. Res. 2024, 11, uhae067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajihara, K.T.; Egan, C.P.; Swift, S.O.I.; Wall, C.B.; Muir, C.D.; Hynson, N.A. Core arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi are predicted by their high abundance-occupancy relationship while host-specific taxa are rare and geographically structured. New Phytol. 2022, 234, 1464–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y.; Wang, Z.; He, Y.; Li, G.; Lv, X.; Zhuang, L. High-throughput sequencing analysis of the rhizosphere arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) community composition associated with Ferula sinkiangensis. BMC Microbiol. 2020, 20, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambrósio, D.L.; Lee, J.H.; Panigrahi, A.K.; Nguyen, T.N.; Cicarelli, R.M.; Günzl, A. Spliceosomal proteomics in Trypanosoma brucei reveal new RNA splicing factors. Eukaryot. Cell 2009, 8, 990–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idondo, L.F.; Colombo, R.P.; Recchi, M.; Silvani, V.A.; Pérgola, M.; Martínez, A.; Godeas, A.M. Detection of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi associated with pecan (Caryaillinoinensis) trees by molecular and morphological approaches. MycoKeys 2018, 38, 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Geel, M.; Busschaert, P.; Honnay, O.; Lievens, B. Evaluation of six primer pairs targeting the nuclear rRNA operon for characterization of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal (AMF) communities using 454 pyrosequencing. J. Microbiol. Methods 2014, 106, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krüger, M.; Stockinger, H.; Krüger, C.; Schüßler, A. DNA-based species level detection of Glomeromycota: One PCR primer set for all arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. New Phytol. 2009, 183, 212–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faggioli, V.; Menoyo, E.; Geml, J.; Kemppainen, M.; Pardo, A.; Salazar, M.J.; Becerra, A.G. Soil lead pollution modifies the structure of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal communities. Mycorrhiza 2019, 29, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Caballero, G.; Caravaca, F.; Roldán, A. The unspecificity of the relationships between the invasive Pennisetum setaceum and mycorrhizal fungi may provide advantages during its establishment at semiarid Mediterranean sites. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 630, 1464–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, M.B.; Augustin, M.A.; Robertson, M.J.; Manners, J.M. The science of food security. npj Sci. Food 2018, 2, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Raza, A.; Song, J.; Janiad, S.; Li, Q.; Huang, M.; Hassan, M.A. Growth-promoting effects of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus Funneliformis mosseae in rice, sesame, sorghum, Egyptian pea and Mexican hat plant. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1549006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, Y.; Shi, J.; Luo, G. Present situation and evaluation of soil nutrients and chemical fertilizer application in Xinjiang farmland. Agro-Sci. 2006, 34, 375–379. [Google Scholar]

- Paravar, A.; Wu, Q.-S. Is a combination of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi more beneficial to enhance drought tolerance than single arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus in Lallemantia species? Environ. Exp. Bot. 2024, 226, 105853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Qu, H.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chao, L.; Liu, H.; Liu, H.; Bao, Y. Changes of root AMF community structure and colonization levels under distribution pattern of geographical substitute for four Stipa species in arid steppe. Microbiol. Res. 2023, 271, 127371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.; Wu, X.; Zhukova, A.; Tang, Z.; Weng, Y.; Li, Z.; Yang, Y. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) species and abundance exhibit different effects on saline-alkaline tolerance in Leymus chinensis. J. Plant Interact. 2020, 15, 266–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, Z.; Hu, R.; Wang, D.; Wang, C.; Chen, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhuge, Y.; Xie, Z. The impact of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on soybean growth strategies in response to salt stress. Plant Soil 2025, 509, 929–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, S.; Tomar, R.S.; Jajoo, A. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) protects photosynthetic apparatus of wheat under drought stress. Photosynth. Res. 2019, 139, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, H.; Chen, R.; Wang, J.; Zhang, J.; Chu, H. Long-term balanced fertilization decreases arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal diversity in an arable soil in North China revealed by 454 pyrosequencing. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 5764–5771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhshandeh, S.; Corneo, P.E.; Mariotte, P.; Kertesz, M.A.; Dijkstra, F.A. Effect of crop rotation on mycorrhizal colonization and wheat yield under different fertilizer treatments. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2017, 247, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Tian, Q.; Liu, Z.; Lei, Y.; Sun, Y. Diversity of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in cotton rhizosphere soil in Shihezi and its surrounding areas, Xinjiang. Cotton Sci. 2022, 34, 69–78. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Y.; Yang, L. Study on AMF diversity of soil adjacent to two tree species in Gongliu wild fruit forest. Agric. Univ. 2022, 7, 38–41. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, F.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, Y. Analysis on planting effect of soil reclamation in saline-alkali wasteland of Tianshan Mountain in Xinjiang. Soil Bull. 2024, 55, 622–633. [Google Scholar]

- Ercolini, D. High-throughput sequencing and metagenomics: Moving forward in the culture-independent analysis of food microbial ecology. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 3148–3155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, K.; Suyama, Y.; Saito, M.; Sugawara, K. A new primer for discrimination of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi with polymerase chain reaction-denature gradient gel electrophoresis. Grassl. Sci. 2005, 51, 179–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Jiang, Y.H.; Yang, Y.; He, Z.; Luo, F.; Zhou, J. Molecular ecological network analyses. BMC Bioinform. 2012, 13, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.; Holmes, S.P. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolyen, E.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.R.; Bokulich, N.A.; Abnet, C.C.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Alexander, H.; Alm, E.J.; Arumugam, M.; Asnicar, F.; et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 852–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quast, C.; Pruesse, E.; Yilmaz, P.; Gerken, J.; Schweer, T.; Yarza, P.; Peplies, J.; Glöckner, F.O. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: Improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, D590–D596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, J.M.; Hayman, D.S. Improved procedures for clearing roots and staining parasitic and vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi for rapid assessment of infection. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 1970, 55, 158-IN18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mc, G.T.; Miller, M.H.; Evans, D.G.; Fairchild, G.L.; Swan, J.A. A new method which gives an objective measure of colonization of roots by vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. New Phytol. 1990, 115, 495–501. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, G.W.; Skipper, H.D. Comparison of Methods to Extract Spores of Vesicular-Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1979, 43, 722–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.S.; Liu, R.S. The latest classification system of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi of the phylum Coccidioides and the list of species. Mycosystema 2017, 36, 820–850. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, K.; Singh, M.; Srivastava, D.K.; Singh, P.K. Exploring the Diversity, Root Colonization, and Morphology of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi in Lamiaceae. J. Basic Microbiol. 2025, 65, e2400379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, L.; Wu, F.; Fan, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, X.; Zhu, J.; Ni, X. Different effects of litter and root inputs on soil enzyme activities in terrestrial ecosystems. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2023, 183, 104764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Cao, J.; Zhang, S.; Wan, C. Effect of earthworms and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on the microbial community and maize growth under salt stress. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2016, 107, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, C.; Chen, J.; Deng, J.; Zhao, F.; Han, X.; Yang, G.; Tong, X.; Feng, Y.; Shelton, S.; Ren, G. Response of microbial diversity to C:N:P stoichiometry in fine root and microbial biomass following afforestation. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2017, 53, 457–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Xia, M.; Guan, F.; Fan, S. Spatial Distribution of Soil Nitrogen, Phosphorus and Potassium Stocks in Moso Bamboo Forests in Subtropical China. Forests 2016, 7, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Feng, X.; Guo, Y.; Ren, C.; Wang, J.; Doughty, R. Elevation gradients affect the differences of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi diversity between root and rhizosphere soil. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2020, 284, 107894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, H.; Pereira, S.I.; Vega, A.; Castro, P.M.; Marques, A.P. Synergistic effects of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and plant growth-promoting bacteria benefit maize growth under increasing soil salinity. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 257, 109982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kashyain, A.S. Standard Method for Determination of Soil Enzyme Activity; Sun, D.; Fu, R., Translators; Science Press: Beijing, China, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J.; Hou, Y.; Sun, C.; Yang, Y. Effects of different hosts on propagation of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Agric. Sci. Bull. 2022, 38, 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Selvakumar, G.; Shagol, C.C.; Kang, Y.; Chung, B.N.; Han, S.G.; Sa, T.M. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi spore propagation using single spore as starter inoculum and a plant host. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2018, 124, 1556–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Lee, S.; Young, J.P. Improved PCR primers for the detection and identification of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2008, 65, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Cuevas, L.V.; Salinas-Escobar, L.A.; Segura-Castruita, M.; Palmeros-Suárez, P.A.; Gómez-Leyva, J.F. Physiological Responses of Agave maximiliana to Inoculation with Autochthonous and Allochthonous Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi. Plants 2023, 12, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martignoni, M.M.; Garnier, J.; Zhang, X.; Rosa, D.; Kokkoris, V.; Tyson, R.C.; Hart, M.M. Co-inoculation with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi differing in carbon sink strength induces a synergistic effect in plant growth. J. Theor. Biol. 2021, 531, 110859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wellburn, A.R. The Spectral Determination of Chlorophylls a and b, as well as Total Carotenoids, Using Various Solvents with Spectrophotometers of Different Resolution. J. Plant Physiol. 1994, 44, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huan, Z.; Changsen, L.; Chenyan, Z.; Liangmiao, F.; Fan, T.; Xinmeng, H.; Wang, P.; Xu, J.; Yang, W. Improvement and optimization of detection method for crop root activity. Jiangsu Agric. Sci. 2022, 50, 191–194. [Google Scholar]

- Špirić, Z.; Stafilov, T.; Vučković, I.; Glad, M. Study of nitrogen pollution in Croatia by moss biomonitoring and Kjeldahl method. J. Environ. Sci. Health A Tox Hazard Subst. Environ. Eng. 2014, 49, 1402–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibnul, N.K.; Tripp, C.P. A simple solution to the problem of selective detection of phosphate and arsenate by the molybdenum blue method. Talanta 2022, 238, 123043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Feng, Y.; Ma, L.; An, J.; Zhang, H.; Cao, M.; Zhu, H.; Kang, W.; Lian, K. A method for determining glyphosate and its metabolite aminomethyl phosphonic acid by gas chromatography-flame photometric detection. J. Chromatogr. A 2019, 1589, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansa, J.; Mozafar, A.; Anken, T.; Ruh, R.; Sanders, I.R.; Frossard, E. Diversity and structure of AMF communities as affected by tillage in a temperate soil. Mycorrhiza 2002, 12, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, D.; Gai, S.; He, X.; Zhang, W.; Hu, P.; Soromotin, A.V.; Kuzyakov, Y.; Wang, K. Habitat heterogeneity drives arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and shrub communities in karst ecosystems. CATENA 2023, 233, 107513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Aarle, I.M.; Olsson, P.A. Fungal lipid accumulation and development of mycelial structures by two arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 69, 6762–6767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniell, T.J.; Husband, R.; Fitter, A.H.; Young, J.P. Molecular diversity of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi colonising arable crops. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2001, 36, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallino, M.; Massa, N.; Lumini, E.; Bianciotto, V.; Berta, G.; Bonfante, P. Assessment of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal diversity in roots of Solidago gigantea growing in a polluted soil in Northern Italy. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 8, 971–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.Y.; Wu, H.; Zu, C.; Li, W.; Guo, X.; Li, M.; Guo, S. Diversity and Community Structure of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi (AMF) in the Rhizospheric Soil of Panax notoginseng in Different Ages. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2023, 56, 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chittavichai, T.; Sathitnaitham, S.; Utthiya, S.; Prompichai, W.; Prommarit, K.; Vuttipongchaikij, S.; Wonnapinij, P. Limitations of 18S rDNA Sequence in Species-Level Classification of Dictyostelids. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delavaux, C.S.; Ramos, R.J.; Stürmer, S.L.; Bever, J.D. An updated LSU database and pipeline for environmental DNA identification of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Mycorrhiza 2024, 34, 369–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Feng, J.; Han, M.; Zhu, B. Responses of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi to nitrogen addition: A meta-analysis. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2020, 26, 7229–7241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.S.; Zhou, M.X.; Zai, X.M.; Zhao, F.G.; Qin, P. Spatio-temporal dynamics of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and soil organic carbon in coastal saline soil of China. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 9781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltruschat, H.; Santos, V.M.; da Silva, D.K.A.; Schellenberg, I.; Deubel, A.; Sieverding, E.; Oehl, F. Unexpectedly high diversity of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in fertile Chernozem croplands in Central Europe. CATENA 2019, 182, 104135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, G.; Liu, Y.; Johnson, N.C.; Olsson, P.A.; Mao, L.; Cheng, G.; Jiang, S.; Du, G.; Feng, H. Interactive influence of light intensity and soil fertility on root-associated arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Plant Soil 2014, 378, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faggioli, V.; Menoyo, E.; Geml, J.; Kemppainen, M.; Pardo, A.; Salazar, M.J.; Becerra, A.G. Soil chemical properties and geographical distance exerted effects on arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal community composition in pear orchards in Jiangsu Province, China. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2019, 142, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oehl, F.; Laczko, E.; Oberholzer, H.-R.; Jansa, J.; Egli, S. Diversity and biogeography of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in agricultural soils. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2017, 53, 777–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazard, C.; Gosling, P.; van der Gast, C.J.; Mitchell, D.T.; Doohan, F.M.; Bending, G.D. The role of local environment and geographical distance in determining community composition of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi at the landscape scale. ISME J. 2013, 7, 498–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.L.; Chen, L.J.; Chen, X.H.; Tan, M.L.; Duan, Z.H.; Wu, Z.J.; Li, X.J.; Fan, X.H. Response of soil enzyme activity to long-term restoration of desertified land. CATENA 2015, 133, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Geng, Q.; Zhang, H.; Bian, C.; Chen, H.Y.H.; Jiang, D.; Xu, X. Global negative effects of nutrient enrichment on arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, plant diversity and ecosystem multifunctionality. New Phytol. 2021, 229, 2957–2969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Luo, P.; Yang, J.; Irfan, M.; Dai, J.; An, N.; Li, N.; Han, X. Responses of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Diversity and Community to 41-Year Rotation Fertilization in Brown Soil Region of Northeast China. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 742651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yi, M.; Pei, Y.; Chen, X.; Xia, T.Y.; Xu, S.G. Analysis on diversity and community structure difference of AMF in roots of healthy and black shank tobacco plants. J. Yunnan Univ. 2023, 45, 186–198. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.; Huang, B.; Wang, F.; Huang, R.; Zheng, X.; Su, Y.; Yin, M. Diversity of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in roots of Panax notoginseng with different ages and its correlation with soil physical and chemical properties. J. South China Agric. 2023, 54, 3217–3227. [Google Scholar]

- denan, S.; Oja, J.; Alatalo, J.M.; Shraim, A.M.; Alsafran, M.; Tedersoo, L.; Zobel, M.; Ahmed, T. Diversity of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and its chemical drivers across dryland habitats. Mycorrhiza 2021, 31, 685–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, H.Y.; Wu, H.; Zu, C.; Li, W.; Guo, X.; Li, M.; Guo, S. Diversity of AM Fungi in Flaveria bidentis and Effects of Dominant Species on Plant Growth. Mycosystema 2023, 42, 692–706. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Zhou, L.; Chen, G.; Yao, M.; Liu, Z.; Li, X.; Yang, X.; Yang, Y.; Cai, D.; Tuerxun, Z. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi enhance drought resistance and alter microbial communities in maize rhizosphere soil. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2025, 37, 103947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shi, W.; Jiang, L. Difference of species diversity of soil arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in different habitats before and after the transformation of natural forest into a single tea garden. J. Northeast For. Univ. 2024, 52, 149–160. [Google Scholar]

- Coutinho, E.S.; Fernandes, G.W.; Berbara, R.L.; Valério, H.M.; Goto, B.T. Variation of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal communities along an altitudinal gradient in rupestrian grasslands in Brazil. Mycorrhiza 2015, 25, 627–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Gast, C.J.; Gosling, P.; Tiwari, B.; Bending, G.D. Spatial scaling of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal diversity is affected by farming practice. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 13, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Chen, S.; Yang, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhao, M. Comparison of Effects of Different Special Fertilizers in Promoting Maize Growth. J. Nanjing Agric. Univ. 2024, 47, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Rashwan, E.; El-Gohary, Y. Impact of different levels of Phosphorus and seed inoculation with Arbuscular mycorrhiza (AM) on growth, yield traits and productivity of wheat. Egypt. J. Agron. 2019, 41, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, G.; Liu, Y.; Gu, L.; Xia, Y.S. Effects of AMF inoculation and crop root separation on soybean growth and phosphorus absorption in purple soil. Soybean Sci. 2015, 34, 436–441+448. [Google Scholar]

- Bowles, T.M.; Barrios-Masias, F.H.; Carlisle, E.A.; Cavagnaro, T.R.; Jackson, L.E. Effects of arbuscular mycorrhizae on tomato yield, nutrient uptake, water relations, and soil carbon dynamics under deficit irrigation in field conditions. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 566–567, 1223–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Li, Q.; Yerger, E.H.; Chen, X.; Shi, Q.; Wan, F. AM fungi facilitate the competitive growth of two invasive plant species, Ambrosia artemisiifolia and Bidens pilosa. Mycorrhiza 2018, 28, 703–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eltigani, A.; Müller, A.; Ngwene, B.; George, E. Physiological and Morphological Responses of Okra (Abelmoschus esculentus L.) to Rhizoglomus irregulare Inoculation under Ample Water and Drought Stress Conditions Are Cultivar Dependent. Plants 2021, 11, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fasusi, O.A.; Amoo, A.E.; Babalola, O.O. Propagation and characterization of viable arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal spores within maize plant (Zea mays L.). J. Sci. Food Agric. 2021, 101, 5834–5841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munkvold, L.; Kjøller, R.; Vestberg, M.; Rosendahl, S.; Jakobsen, I. High functional diversity within species of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. New Phytol. 2004, 164, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basiru, S.; Mhand, K.A.S.; Hijri, M. Disentangling arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and bacteria at the soil-root interface. Mycorrhiza 2023, 33, 119–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wu, M.; Liu, J.; Qu, Y.; Gao, Y.; Ren, A. Tripartite Interactions Between Endophytic Fungi, Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi, and Leymus chinensis. Microb. Ecol. 2020, 79, 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, N.; Handa, Y.; Tsuzuki, S.; Kojima, M.; Sakakibara, H.; Kawaguchi, M. Gibberellins interfere with symbiosis signaling and gene expression and alter colonization by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in Lotus japonicus. Plant Physiol. 2015, 167, 545–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearson, J.N.; LAbbott, K.; Jasper, D.A. Phosphorus, soluble carbohydrates and the competition between two arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi colonizing subterranean clover. New Phytol. 1994, 127, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Der Heijden, M.G.A.; Wiemken, A.; Sanders, I.R. Different arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi alter coexistence and resource distribution between co-occurring plant. New Phytol. 2003, 157, 569–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Phylum Glomeromycota Class Glomeromycetes Orders (3) | Families (7) | Genera (11) |

|---|---|---|

| Glomerales | Glomeraceae | Glomus |

| Septoglomus | ||

| Rhizophagus | ||

| unclassified_Glomeraceae | ||

| Claroideoglomeraceae | Claroideoglomus | |

| unclassified_Glomerales | unclassified_Glomerales | |

| Diversisporales | Acaulosporaceae | Acaulospora |

| Diversisporaceae | Diversispora | |

| Gigasporaceae | Scutellospora | |

| Gigaspora | ||

| unclassified_Glomeromycetes | unclassified_Glomeromycetes | unclassified_Glomeromycetes |

| Phylum: Glomeromycota Class: Glomeromycetes Orders (3) | Families (6) | Genera (9) | Species (14) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glomerales | Glomeraceae | Glomus | Glomus melanosporum |

| Glomus clarum | |||

| Glomus constrictum | |||

| Rhizophagus | Rhizophagus intraradices | ||

| Septoglomus | Septoglomus constrictum | ||

| Diversisporales | Acaulosporaceae | Acaulospora | Acaulospora denticulata |

| Acaulospora elegans | |||

| Acaulospora tuberculata | |||

| Entrophospora | Entrophospora colombiana | ||

| Diversisporaceae | Diversispora | Diversispora spuecum | |

| Gigasporaceae | Scutellospora | Scutellospora calospora | |

| Archaeosporales | Archaeosporaceae | Archaeospora | Archaeospora leptoticha |

| Archaeospora schenckii | |||

| Ambisporaceae | Ambispora | Ambispora jimgerdemannii |

| Species | IF | RA | IV | Region |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glomus melanosporum | 95.00% | 38.33% | 66.66% | M1–M3, H1, H2, S1, S2, S3, B1–B3, T1–T4, Y1–Y4 |

| Glomus clarum | 20.00% | 5.56% | 12.78% | H3, B3, Y3, Y4 |

| Glomus constrictum | 50.00% | 8.72% | 29.36% | M2, M3, H1, S1, B2, T2, T3, Y2, Y4 |

| Rhizophagus intraradices | 85.00% | 30.25% | 56.46% | M1–M3, H1–H3, S1, S2, S3, B1–B3, T1–T4 |

| Septoglomus constrictum | 60.00% | 7.03% | 33.51% | M1–M3, H1, H2, S1, S2, B1, B3, T1, T4, Y3 |

| Acaulospora denticulata | 60.00% | 8.85% | 34.43% | M1, M3, H3, S1–S3, B1, B3, T1, T4, Y1, Y3 |

| Acaulospora elegans | 10.00% | 1.06% | 5.53% | M2, S2 |

| Acaulospora tuberculata | 10.00% | 0.49% | 5.24% | M2, S2 |

| Entrophospora colombiana | 15.00% | 0.68% | 7.84% | M1, M2, S1 |

| Diversispora spuecum | 50.00% | 7.38% | 28.69% | H1, H2, B2, B3, T2, T3, T4, Y2, Y3, Y4 |

| Scutellospora calospora | 20.00% | 3.55% | 11.78% | H2, B3, T4, Y3 |

| Archaeospora leptoticha | 75.00% | 10.07% | 42.54% | M3, H1, H3, S2, S3, B1, B2, T1–T4, Y1, Y2, Y4 |

| Archaeospora schenckii | 60.00% | 4.91% | 32.46% | M3, H1, H3, S2, S3, B1, B2, T1, T2, Y2, Y4 |

| Ambispora jimgerdemannii | 10.00% | 3.38% | 6.69% | H2, T4 |

| Region | Sample Plot Number | Vesicles | Arbuscules | Hyphae | Overall Infestation Rate | Average Total Infection Rate in Each Region |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Changji Hui autonomous prefecture | M1 | 4.68% | 8.54% | 34.27% | 62.46% | 72.24% |

| M2 | 2.15% | 16.49% | 40.14% | 83.51% | ||

| M3 | 3.13% | 13.48% | 35.74% | 66.02% | ||

| H1 | 17.98% | 6.27% | 38.15% | 74.66% | ||

| H2 | 0.31% | 16.21% | 45.26% | 76.76% | ||

| H3 | 6.60% | 12.18% | 35.03% | 70.05% | ||

| ShiHeZi | S1 | 2.61% | 7.35% | 38.15% | 79.38% | 68.60% |

| S2 | 3.53% | 13.04% | 30.98% | 56.79% | ||

| S3 | 1.47% | 13.27% | 44.25% | 69.62% | ||

| Bortal Mongolian Autonomous Prefecture | B1 | 37.18% | 3.85% | 15.38% | 57.05% | 64.79% |

| B2 | 2.94% | 34.12% | 17.06% | 60.59% | ||

| B3 | 3.82% | 19.08% | 36.26% | 76.72% | ||

| Ilikazak Autonomous Prefecture | Y1 | 1.31% | 10.76% | 47.51% | 72.97% | 72.41% |

| Y2 | 0.93% | 12.77% | 41.12% | 71.03% | ||

| Y3 | 7.75% | 9.25% | 37.75% | 76.75% | ||

| Y4 | 5.20% | 7.43% | 41.83% | 75.50% | ||

| T1 | 0.97% | 11.97% | 37.86% | 67.64% | ||

| T2 | 6.35% | 9.79% | 41.80% | 78.31% | ||

| T3 | 2.86% | 9.35% | 38.70% | 69.09% | ||

| T4 | 5.08% | 9.64% | 21.83% | 68.02% |

| Pearson Correlation | Sig. (Double Tail) | |

|---|---|---|

| pH | 0.113 | 0.634 |

| EC | −0.129 | 0.589 |

| SOM | −0.116 | 0.627 |

| TN | −0.039 | 0.872 |

| TP | 0.062 | 0.795 |

| TK | 0.233 | 0.324 |

| AN | 0.029 | 0.905 |

| AP | 0.035 | 0.883 |

| AK | −0.253 | 0.282 |

| S_ACP | 0.155 | 0.513 |

| PROT | −0.034 | 0.886 |

| SAC | −0.056 | 0.814 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhao, Z.; Zhang, W.; Xie, W.; Lei, Y.; Li, Y.; Sun, Y. Diversity of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi in Rhizosphere Soil of Maize in Northern Xinjiang, China, and Evaluation of Inoculation Benefits of Three Strains. J. Fungi 2026, 12, 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof12010027

Zhao Z, Zhang W, Xie W, Lei Y, Li Y, Sun Y. Diversity of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi in Rhizosphere Soil of Maize in Northern Xinjiang, China, and Evaluation of Inoculation Benefits of Three Strains. Journal of Fungi. 2026; 12(1):27. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof12010027

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Ziwen, Wenqian Zhang, Wendan Xie, Yonghui Lei, Yang Li, and Yanfei Sun. 2026. "Diversity of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi in Rhizosphere Soil of Maize in Northern Xinjiang, China, and Evaluation of Inoculation Benefits of Three Strains" Journal of Fungi 12, no. 1: 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof12010027

APA StyleZhao, Z., Zhang, W., Xie, W., Lei, Y., Li, Y., & Sun, Y. (2026). Diversity of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi in Rhizosphere Soil of Maize in Northern Xinjiang, China, and Evaluation of Inoculation Benefits of Three Strains. Journal of Fungi, 12(1), 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof12010027