Amphibian-Derived Peptide Analog TB_KKG6K: A Powerful Drug Candidate Against Candida albicans with Anti-Biofilm Efficacy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Peptide Synthesis

2.2. Drug Susceptibility Testing

2.3. Checkerboard Assay

2.4. Drug Adaptation Experiment

2.5. C. albicans Biofilm Cultivation on Silicone Elastomer Discs

2.6. Antifungal Therapy of Sessile C. albicans Cells

2.7. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

2.8. Confocal Microscopy

2.9. RNA Extraction and Quantitative PCR

2.10. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. TB_KKG6K Exhibits Strong Sustained Candidacidal Efficacy

3.2. TB_KKG6K Shows No Adverse Interference with Standard Antifungal Drugs

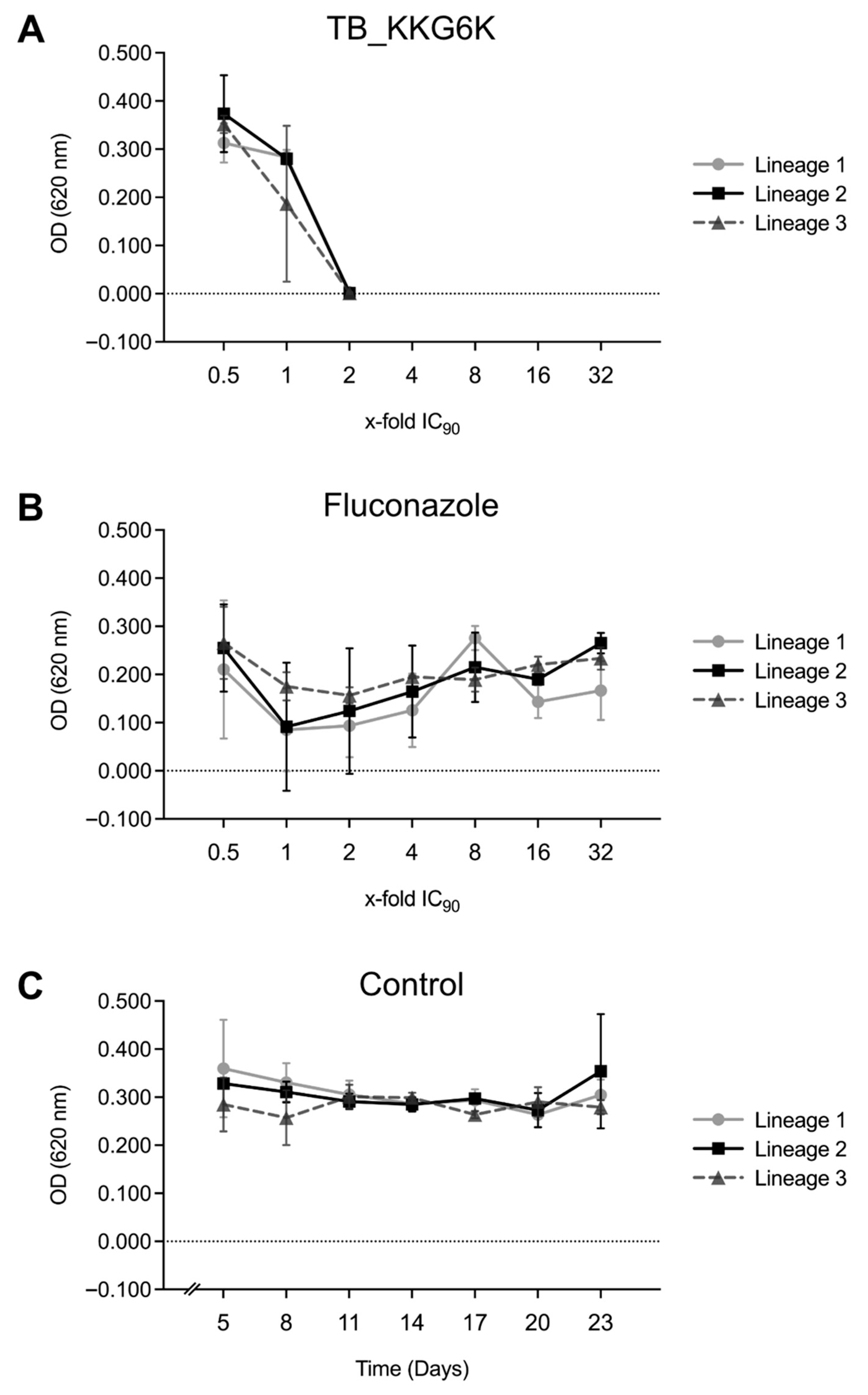

3.3. TB_KKG6K Has Low Potential to Induce Adaptive Mechanisms in C. albicans

3.4. TB_KKG6K Inhibits C. albicans Biofilm Development

3.5. TB_KKG6K Reduces ECM Formation in C. albicans Biofilm

3.6. TB_KKG6K Induces Transcriptional Deregulation in Sessile C. albicans Cells

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nobile, C.J.; Johnson, A.D. Candida albicans Biofilms and Human Disease. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2015, 69, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, M.; Nobile, C.J. Candida albicans biofilms: Development, regulation, and molecular mechanisms. Microbes Infect. 2016, 18, 310–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atriwal, T.; Azeem, K.; Husain, F.M.; Hussain, A.; Khan, M.N.; Alajmi, M.F.; Abid, M. Mechanistic Understanding of Candida albicans Biofilm Formation and Approaches for Its Inhibition. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 638609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas-Rüddel, D.O.; Schlattmann, P.; Pletz, M.; Kurzai, O.; Bloos, F. Risk Factors for Invasive Candida Infection in Critically Ill Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Chest 2022, 161, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lass-Flörl, C.; Kanj, S.S.; Govender, N.P.; Thompson, G.R.; Ostrosky-Zeichner, L.; Govrins, M.A. Invasive candidiasis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2024, 10, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkel, J.S.; Mitchell, A.P. Genetic control of Candida albicans biofilm development. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2011, 9, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandra, J.; Kuhn, D.M.; Mukherjee, P.K.; Hoyer, L.L.; McCormick, T.; Ghannoum, M.A. Biofilm formation by the fungal pathogen Candida albicans: Development, architecture, and drug resistance. J. Bacteriol. 2001, 183, 5385–5394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nett, J.; Andes, D. Candida albicans biofilm development, modeling a host-pathogen interaction. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2006, 9, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinovská, Z.; Čonková, E.; Váczi, P. Biofilm Formation in Medically Important Candida Species. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- d’Enfert, C. Biofilms and their role in the resistance of pathogenic Candida to antifungal agents. Curr. Drug Targets 2006, 7, 465–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramage, G.; Martínez, J.P.; López-Ribot, J.L. Candida biofilms on implanted biomaterials: A clinically significant problem. FEMS Yeast Res. 2006, 6, 979–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talpaert, M.J.; Balfour, A.; Stevens, S.; Baker, M.; Muhlschlegel, F.A.; Gourlay, C.W. Candida biofilm formation on voice prostheses. J. Med. Microbiol. 2015, 64, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouza, E.; Guinea, J.; Guembe, M. The Role of Antifungals against Candida Biofilm in Catheter-Related Candidemia. Antibiotics 2014, 4, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponde, N.O.; Lortal, L.; Ramage, G.; Naglik, J.R.; Richardson, J.P. Candida albicans biofilms and polymicrobial interactions. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 47, 91–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateus, C.; Crow, S.A.; Ahearn, D.G. Adherence of Candida albicans to silicone induces immediate enhanced tolerance to fluconazole. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004, 48, 3358–3366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, P.K.; Chandra, J.; Kuhn, D.M.; Ghannoum, M.A. Mechanism of fluconazole resistance in Candida albicans biofilms: Phase-specific role of efflux pumps and membrane sterols. Infect. Immun. 2003, 71, 4333–4340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramage, G.; Bachmann, S.; Patterson, T.F.; Wickes, B.L.; López-Ribot, J.L. Investigation of multidrug efflux pumps in relation to fluconazole resistance in Candida albicans biofilms. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2002, 49, 973–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Andrea, L.D.; Romanelli, A. Temporins: Multifunctional Peptides from Frog Skin. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avitabile, C.; D’Andrea, L.D.; D’Aversa, E.; Milani, R.; Gambari, R.; Romanelli, A. Effect of Acylation on the Antimicrobial Activity of Temporin B Analogues. ChemMedChem 2018, 13, 1549–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakar, A.; Holzknecht, J.; Dubrac, S.; Gelmi, M.L.; Romanelli, A.; Marx, F. New Perspectives in the Antimicrobial Activity of the Amphibian Temporin B: Peptide Analogs Are Effective Inhibitors of Candida albicans Growth. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakar, A.; Sastré-Velásquez, L.E.; Hess, M.; Galgóczy, L.; Papp, C.; Holzknecht, J.; Romanelli, A.; Váradi, G.; Malanovic, N.; Marx, F. The Membrane Activity of the Amphibian Temporin B Peptide Analog TB_KKG6K Sheds Light on the Mechanism That Kills Candida albicans. mSphere 2022, 7, e0029022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schöpf, C.; Knapp, M.; Scheler, J.; Coraça-Huber, D.C.; Romanelli, A.; Ladurner, P.; Seybold, A.C.; Binder, U.; Würzner, R.; Marx, F. The antibacterial activity and therapeutic potential of the amphibian-derived peptide TB_KKG6K. mSphere 2025, 10, e0101624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EUCAST. EUCAST Definitive Document, E.Def 7.4: Method for the Determination of Broth Dilution Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations of Antifungal Agents for Yeasts. 2023. Available online: https://www.eucast.org/fungi-afst/methodology-and-instructions/ast-of-yeasts/ (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Meletiadis, J.; Verweij, P.E.; TeDorsthorst, D.T.; Meis, J.F.; Mouton, J.W. Assessing in vitro combinations of antifungal drugs against yeasts and filamentous fungi: Comparison of different drug interaction models. Med. Mycol. 2005, 43, 133–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács, R.; Nagy, F.; Tóth, Z.; Forgács, L.; Tóth, L.; Váradi, G.; Tóth, G.K.; Vadászi, K.; Borman, A.M.; Majoros, L.; et al. The Neosartorya fischeri Antifungal Protein 2 (NFAP2): A New Potential Weapon against Multidrug-Resistant Candida auris Biofilms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bende, G.; Zsindely, N.; Laczi, K.; Kristóffy, Z.; Papp, C.; Farkas, A.; Tóth, L.; Sáringer, S.; Bodai, L.; Rákhely, G.; et al. The Neosartorya (Aspergillus) fischeri antifungal protein NFAP2 has low potential to trigger resistance development in Candida albicans in vitro. Microbiol. Spectr. 2025, 13, e0127324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geschwindt, A. Studies on the Antifungal Potential of Small, Cationic, Peptides Against Candida albicans. Master’s Thesis, Medical University of Innsbruck, Innsbruck, Austria, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, V.C.; Souza, M.T.; Zanotto, E.D.; Watanabe, E.; Coraça-Huber, D. Biofilm Formation and Expression of Virulence Genes of Microorganisms Grown in Contact with a New Bioactive Glass. Pathogens 2020, 9, 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Su, C.; Liu, H. A GATA transcription factor recruits Hda1 in response to reduced Tor1 signaling to establish a hyphal chromatin state in Candida albicans. PLoS Pathog. 2012, 8, e1002663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sah, S.K.; Yadav, A.; Kruppa, M.D.; Rustchenko, E. Identification of 10 genes on Candida albicans chromosome 5 that control surface exposure of the immunogenic cell wall epitope β-glucan and cell wall remodeling in caspofungin-adapted mutants. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e0329523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.L.; Li, H.; Yan, T.H.; Fang, T.; Wu, H.; Cao, Y.B.; Lu, H.; Jiang, Y.Y.; Yang, F. Aneuploidy Mediates Rapid Adaptation to a Subinhibitory Amount of Fluconazole in Candida albicans. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e0301622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerstein, A.C.; Berman, J. Genetic Background Influences Mean and Heterogeneity of Drug Responses and Genome Stability during Evolution in Fluconazole. mSphere 2020, 5, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morschhäuser, J. The development of fluconazole resistance in Candida albicans—An example of microevolution of a fungal pathogen. J. Microbiol. 2016, 54, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCall, A.D.; Pathirana, R.U.; Prabhakar, A.; Cullen, P.J.; Edgerton, M. Author Correction: Candida albicans biofilm development is governed by cooperative attachment and adhesion maintenance proteins. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2021, 7, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wesenberg-Ward, K.E.; Tyler, B.J.; Sears, J.T. Adhesion and biofilm formation of Candida albicans on native and Pluronic-treated polystyrene. Biofilms 2005, 2, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonhomme, J.; d’Enfert, C. Candida albicans biofilms: Building a heterogeneous, drug-tolerant environment. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2013, 16, 398–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Assis, L.J.; Bain, J.M.; Liddle, C.; Leaves, I.; Hacker, C.; Peres da Silva, R.; Yuecel, R.; Bebes, A.; Stead, D.; Childers, D.S.; et al. Nature of β-1,3-Glucan-Exposing Features on Candida albicans Cell Wall and Their Modulation. mBio 2022, 13, e0260522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebecker, B.; Vlaic, S.; Conrad, T.; Bauer, M.; Brunke, S.; Kapitan, M.; Linde, J.; Hube, B.; Jacobsen, I.D. Dual-species transcriptional profiling during systemic candidiasis reveals organ-specific host-pathogen interactions. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 36055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whaley, S.G.; Berkow, E.L.; Rybak, J.M.; Nishimoto, A.T.; Barker, K.S.; Rogers, P.D. Azole Antifungal Resistance in Candida albicans and Emerging Non-albicans Candida Species. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selmecki, A.; Forche, A.; Berman, J. Aneuploidy and isochromosome formation in drug-resistant Candida albicans. Science 2006, 313, 367–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pristov, K.E.; Ghannoum, M.A. Resistance of Candida to azoles and echinocandins worldwide. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2019, 25, 792–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, D.H.; Coleman, D.C.; O’Connell, B.C. Binding, internalisation and degradation of histatin 3 in histatin-resistant derivatives of Candida albicans. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2003, 220, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donlan, R.M. Biofilms: Microbial life on surfaces. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2002, 8, 881–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flemming, H.C.; van Hullebusch, E.D.; Neu, T.R.; Nielsen, P.H.; Seviour, T.; Stoodley, P.; Wingender, J.; Wuertz, S. The biofilm matrix: Multitasking in a shared space. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 70–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohse, M.B.; Gulati, M.; Johnson, A.D.; Nobile, C.J. Development and regulation of single- and multi-species Candida albicans biofilms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zare, M.; Ghomi, E.R.; Venkatraman, P.D.; Ramakrishna, S. Silicone-based biomaterials for biomedical applications: Antimicrobial strategies and 3D printing technologies. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2021, 138, 50969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, C.G.; Chaturvedi, A.K.; Lazzell, A.L.; Powell, A.T.; Saville, S.P.; McHardy, S.F.; Lopez-Ribot, J.L. A novel small molecule inhibitor of Candida albicans biofilm formation, filamentation and virulence with low potential for the development of resistance. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2015, 1, 15012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara, H.H.; Lopez-Ribot, J.L. Inhibition of Mixed Biofilms of Candida albicans and Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus by Positively Charged Silver Nanoparticles and Functionalized Silicone Elastomers. Pathogens 2020, 9, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConnell, G.; Rooney, L.M.; Sandison, M.E.; Hoskisson, P.A.; Baxter, K.J. A simple silicone elastomer colonization model highlights complexities of Candida albicans and Staphylococcus aureus interactions in biofilm formation. J. Med. Microbiol. 2025, 74, 002047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumpakha, R.; Gordon, D.M. Occidiofungin inhibition of Candida biofilm formation on silicone elastomer surface. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e0246023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceresa, C.; Tessarolo, F.; Maniglio, D.; Caola, I.; Nollo, G.; Rinaldi, M.; Letizia, F. Inhibition of Candida albicans biofilm by lipopeptide AC7 coated medical-grade silicone in combination with farnesol. AIMS Bioeng. 2018, 5, 192–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.S.; Kim, Y.S.; Han, I.; Kim, M.H.; Jung, M.H.; Park, H.K. Quantitative and qualitative analyses of the cell death process in Candida albicans treated by antifungal agents. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e28176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grela, E.; Zdybicka-Barabas, A.; Pawlikowska-Pawlega, B.; Cytrynska, M.; Wlodarczyk, M.; Grudzinski, W.; Luchowski, R.; Gruszecki, W.I. Modes of the antibiotic activity of amphotericin B against Candida albicans. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 17029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gow, N.A.; Hube, B. Importance of the Candida albicans cell wall during commensalism and infection. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2012, 15, 406–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Rubio, R.; de Oliveira, H.C.; Rivera, J.; Trevijano-Contador, N. The Fungal Cell Wall: Candida, Cryptococcus, and Aspergillus Species. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, B.J.; Hageage, G.J., Jr. Calcofluor White: A Review of its Uses and Applications in Clinical Mycology and Parasitology. Lab. Med. 2003, 34, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokol-Anderson, M.L.; Brajtburg, J.; Medoff, G. Amphotericin B-induced oxidative damage and killing of Candida albicans. J. Infect. Dis. 1986, 154, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesa-Arango, A.C.; Trevijano-Contador, N.; Román, E.; Sánchez-Fresneda, R.; Casas, C.; Herrero, E.; Argüelles, J.C.; Pla, J.; Cuenca-Estrella, M.; Zaragoza, O. The production of reactive oxygen species is a universal action mechanism of Amphotericin B against pathogenic yeasts and contributes to the fungicidal effect of this drug. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 6627–6638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesa-Arango, A.C.; Scorzoni, L.; Zaragoza, O. It only takes one to do many jobs: Amphotericin B as antifungal and immunomodulatory drug. Front. Microbiol. 2012, 3, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, T.M.; Clay, M.C.; Cioffi, A.G.; Diaz, K.A.; Hisao, G.S.; Tuttle, M.D.; Nieuwkoop, A.J.; Comellas, G.; Maryum, N.; Wang, S.; et al. Amphotericin forms an extramembranous and fungicidal sterol sponge. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2014, 10, 400–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carolus, H.; Pierson, S.; Lagrou, K.; Van Dijck, P. Amphotericin B and Other Polyenes-Discovery, Clinical Use, Mode of Action and Drug Resistance. J. Fungi 2020, 6, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dominguez, E.; Zarnowski, R.; Sanchez, H.; Covelli, A.S.; Westler, W.M.; Azadi, P.; Nett, J.; Mitchell, A.P.; Andes, D.R. Conservation and Divergence in the Candida Species Biofilm Matrix Mannan-Glucan Complex Structure, Function, and Genetic Control. mBio 2018, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, K.F.; Zarnowski, R.; Andes, D.R. Fungal Super Glue: The Biofilm Matrix and Its Composition, Assembly, and Functions. PLoS Pathog. 2016, 12, e1005828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nett, J.; Lincoln, L.; Marchillo, K.; Massey, R.; Holoyda, K.; Hoff, B.; VanHandel, M.; Andes, D. Putative role of beta-1,3 glucans in Candida albicans biofilm resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2007, 51, 510–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkacz, J.S.; Cybulska, E.B.; Lampen, J.O. Specific staining of wall mannan in yeast cells with fluorescein-conjugated concanavalin A. J. Bacteriol. 1971, 105, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben-Ami, R.; Garcia-Effron, G.; Lewis, R.E.; Gamarra, S.; Leventakos, K.; Perlin, D.S.; Kontoyiannis, D.P. Fitness and virulence costs of Candida albicans FKS1 hot spot mutations associated with echinocandin resistance. J. Infect. Dis. 2011, 204, 626–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Ma, S.; Leonhard, M.; Moser, D.; Schneider-Stickler, B. β-1,3-glucanase disrupts biofilm formation and increases antifungal susceptibility of Candida albicans DAY185. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 108, 942–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Ma, S.; Ding, T.; Ludwig, R.; Lee, J.; Xu, J. Enhancing the Antibiofilm Activity of β-1,3-Glucanase-Functionalized Nanoparticles Loaded with Amphotericin B Against Candida albicans Biofilm. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 815091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Hua, H.; Zhou, P. Magnolol as a potent antifungal agent inhibits Candida albicans virulence factors via the PKC and Cek1 MAPK signaling pathways. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 935322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, W.; Lu, J.; Gao, C.; Liu, Q.; Yao, W.; Wang, T.; Wang, X.; Wang, Z. Isobavachalcone exhibits antifungal and antibiofilm effects against C. albicans by disrupting cell wall/membrane integrity and inducing apoptosis and autophagy. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1336773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deveau, A.; Hogan, D.A. Linking quorum sensing regulation and biofilm formation by Candida albicans. Methods Mol. Biol. 2011, 692, 219–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cleary, I.A.; Lazzell, A.L.; Monteagudo, C.; Thomas, D.P.; Saville, S.P. BRG1 and NRG1 form a novel feedback circuit regulating Candida albicans hypha formation and virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 2012, 85, 557–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Cravener, M.; Solis, N.; Filler, S.G.; Mitchell, A.P. A Brg1-Rme1 circuit in Candida albicans hyphal gene regulation. mBio 2024, 15, e0187224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, W.; Acosta-Zaldivar, M.; Flanagan, P.R.; Liu, N.N.; Jani, N.; Fierro, J.F.; Andrés, M.T.; Moran, G.P.; Köhler, J.R. Stress- and metabolic responses of Candida albicans require Tor1 kinase N-terminal HEAT repeats. PLoS Pathog. 2022, 18, e1010089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.; Lu, Y.; Liu, H. Reduced TOR signaling sustains hyphal development in Candida albicans by lowering Hog1 basal activity. Mol. Biol. Cell 2013, 24, 385–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walraven, C.J.; Lee, S.A. Antifungal lock therapy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 57, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács, R.; Majoros, L. Antifungal lock therapy: An eternal promise or an effective alternative therapeutic approach? Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 74, 851–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkuş-Dağdeviren, Z.B.; Saleh, A.; Schöpf, C.; Truszkowska, M.; Bratschun-Khan, D.; Fürst, A.; Seybold, A.; Offterdinger, M.; Marx, F.; Bernkop-Schnürch, A. Phosphatase-degradable nanoparticles: A game-changing approach for the delivery of antifungal proteins. J. Colloid. Interface Sci. 2023, 646, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lombana, A.; Raja, Z.; Casale, S.; Pradier, C.M.; Foulon, T.; Ladram, A.; Humblot, V. Temporin-SHa peptides grafted on gold surfaces display antibacterial activity. J. Pept. Sci. 2014, 20, 563–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oger, P.C.; Piesse, C.; Ladram, A.; Humblot, V. Engineering of Antimicrobial Surfaces by Using Temporin Analogs to Tune the Biocidal/antiadhesive Effect. Molecules 2019, 24, 814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Media/Solution | Composition $ |

|---|---|

| Potato Dextrose Broth (PDB) | 0.65% Potato infusion, 2% Glucose |

| Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) | Potato Dextrose Broth, 2% Agar |

| Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) | 0.05% KH2PO4, 0.28% K2HPO4, 0.9% NaCl, pH 7.4 |

| Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (D-PBS) | 0.02% KCl, 0.02% KH2PO4, 0.8% NaCl, 0.115% Na2HPO4, pH 7.0 |

| Yeast Peptone D-Glucose (YPD) Agar | 1% Yeast extract, 2% Peptone, 2% Glucose, 2% Agar |

| Gene | Orientation | Sequence 5′–3′ | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACT1 | Forward | GCTGGTAGAGACTTGACCAACCA | [28] |

| Reverse | GACAATTTCTCTTTCAGCACTAGTAGTGA | ||

| EFB1 | Forward | CAGCCGCTTCTGGTTCTGCT | This study |

| Reverse | AGCAGCCTTCTTAGCAGCGT | ||

| BRG1 | Forward | AGCTGGTGTGCCACCTCCAC | [30] |

| Reverse | TACCACACCTGTGACATCTG | ||

| FKS1 | Forward | GGATATCAAGACCAAGCCAACTA | [31] |

| Reverse | CCAGGAGTTTGACCACCATAA |

| MIC90 [µM] | MFC [µM] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | 24 h | 48 h | 24 h | 48 h |

| TB_KKG6K | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Amphotericin B | 0.14 | 0.27 | 0.27 | 0.27 |

| Median (Range) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agent | MIC90 [µM] | FICA [TB_KKG6K] | FICB [Licensed Antifungal] | FICI [FICA + FICB] | Interpretation |

| TB_KKG6K | 2 | - | - | - | - |

| Amphotericin B | 0.14 | 0.5 (0.25–0.5) | 0.5 (0.25–0.5) | 0.75 (0.75–1) | Additive |

| Caspofungin | 0.11 | 0.5 (0.25–0.5) | 0.13 (0.06–0.5) | 0.63 (0.56–0.75) | Additive |

| Fluconazole | 6.5 | 0.5 (0.5–1) | 0.5 (0.5–1) | 1.5 (1–1.5) | Indifferent |

| 5-FC | 1.9 | 1 | 1 | 2 | Indifferent |

| 4 h Treatment | 24 h Treatment | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFU cm−2 | log10 Difference & | Survival [%] # | CFU cm−2 | log10 Difference & | Survival [%] # | ||

| Control | (1.85 ± 0.56) × 106 | 0 | 100 | (3.42 ± 0.86) × 106 | 0 | 100 | |

| TB_KKG6K | 2 µM | (1.73 ± 0.52) × 106 | −0.03 ± 0.07 | 95.4 ± 13.8 | (4.75 ± 1.72) × 106 | +0.13 ± 0.05 | 134.9 ± 16.2 |

| 5 µM | (8.87 ± 0.74) × 105 * | −0.30 ± 0.13 | 52.9 ± 16.7 | (3.36 ± 1.55) × 106 | −0.06 ± 0.18 | 93.0 ± 33.8 | |

| 10 µM | (3.34 ± 2.58) × 105 ** | −0.92 ± 0.35 | 16.0 ± 11.5 | (1.56 ± 0.09) × 106 | −0.33 ± 0.12 | 48.9 ± 14.4 | |

| 50 µM | (1.14 ± 0.37) × 104 ** | −2.21 ± 0.28 | 0.8 ± 0.5 | (1.21 ± 0.97) × 105 * | −1.58 ± 0.45 | 4.5 ± 4.6 | |

| Amphotericin B | (2.39 ± 0.94) × 103 ** | −2.90 ± 0.10 | 0.1 ± 0.0 | (2.22 ± 0.66) × 104 * | −2.20 ± 0.06 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Schöpf, C.; Geschwindt, A.; Knapp, M.; Seybold, A.C.; Coraça-Huber, D.C.; Ausserlechner, M.J.; Romanelli, A.; Marx, F. Amphibian-Derived Peptide Analog TB_KKG6K: A Powerful Drug Candidate Against Candida albicans with Anti-Biofilm Efficacy. J. Fungi 2026, 12, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof12010011

Schöpf C, Geschwindt A, Knapp M, Seybold AC, Coraça-Huber DC, Ausserlechner MJ, Romanelli A, Marx F. Amphibian-Derived Peptide Analog TB_KKG6K: A Powerful Drug Candidate Against Candida albicans with Anti-Biofilm Efficacy. Journal of Fungi. 2026; 12(1):11. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof12010011

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchöpf, Cristina, Anik Geschwindt, Magdalena Knapp, Anna C. Seybold, Débora C. Coraça-Huber, Michael J. Ausserlechner, Alessandra Romanelli, and Florentine Marx. 2026. "Amphibian-Derived Peptide Analog TB_KKG6K: A Powerful Drug Candidate Against Candida albicans with Anti-Biofilm Efficacy" Journal of Fungi 12, no. 1: 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof12010011

APA StyleSchöpf, C., Geschwindt, A., Knapp, M., Seybold, A. C., Coraça-Huber, D. C., Ausserlechner, M. J., Romanelli, A., & Marx, F. (2026). Amphibian-Derived Peptide Analog TB_KKG6K: A Powerful Drug Candidate Against Candida albicans with Anti-Biofilm Efficacy. Journal of Fungi, 12(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof12010011