An Overview of Systematic Reviews of Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) for the Diagnosis of Invasive Aspergillosis in Immunocompromised People: A Report of the Fungal PCR Initiative (FPCRI)—An ISHAM Working Group

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Study Selection and Data Extraction

2.4. Assessment of Methodological Quality of Systematic Reviews

2.5. Summary of the Evidence, Subgroups Analisis, and Appraisal of the Quality of Evidence

3. Results

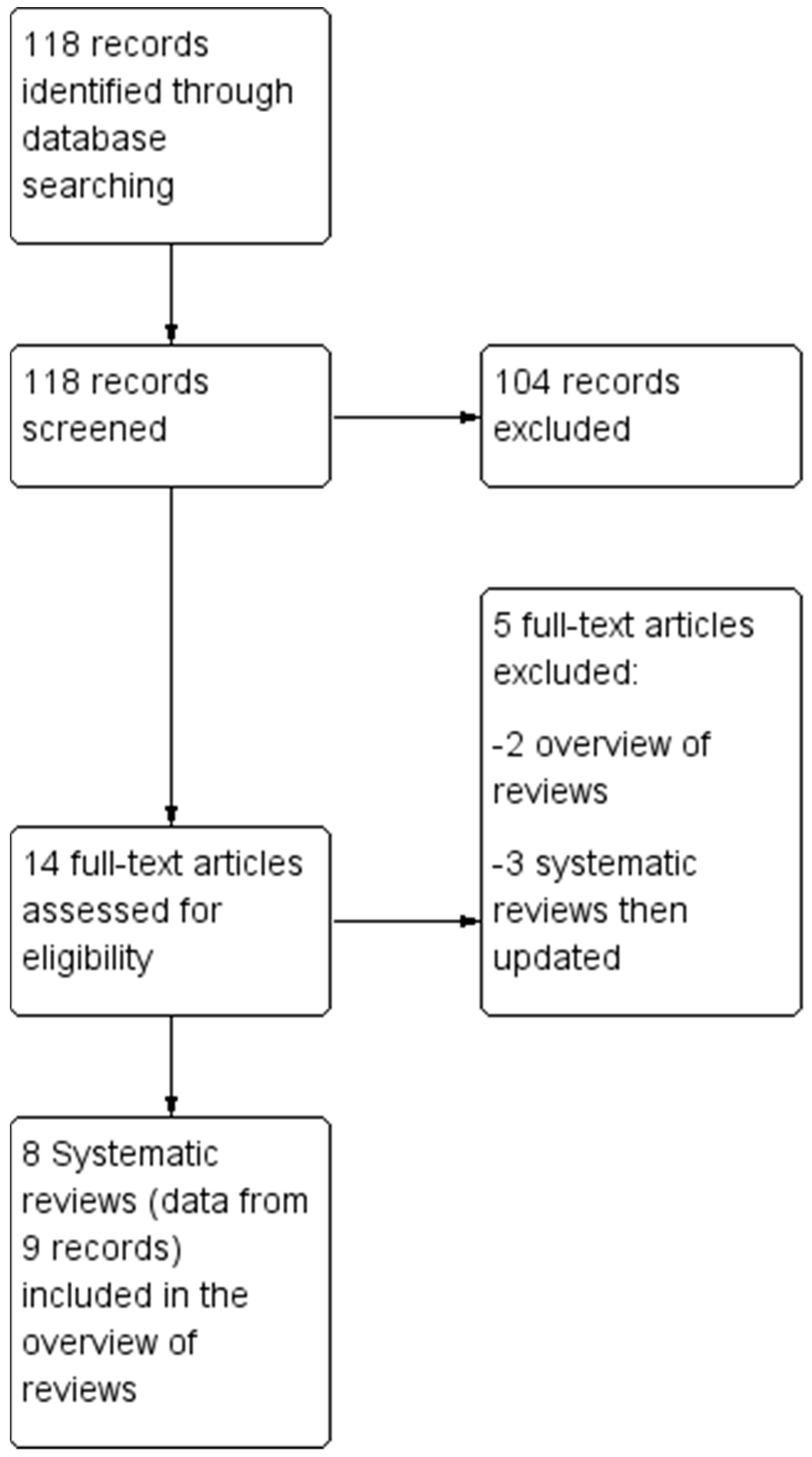

3.1. Description of the Studies

3.2. Methodological Quality of the SRs with the AMSTAR-2

- Did the research questions and inclusion criteria for the review include the components of PICO (patients, index test, comparator, accuracy as outcome)?

- Did the report of the review contain an explicit statement that the review methods were established prior to the conduct of the review and did the report justify any significant deviations from the protocol?

- Did the review authors explain their selection of the study designs for inclusion in the review?

- Did the review authors use a comprehensive literature search strategy?

- Did the review authors perform study selection in duplicate?

- Did the review authors perform data extraction in duplicate?

- Did the review authors provide a list of excluded studies and justify the exclusions?

- Did the review authors describe the included studies in adequate detail?

- Did the review authors use a satisfactory technique for assessing the risk of bias (RoB) in individual studies that were included in the review?

- Did the review authors report on the sources of funding for the studies included in the review?

- If meta-analysis was performed did the review authors use appropriate methods for statistical combination of results?

- If meta-analysis was performed, did the review authors assess the potential impact of RoB in individual studies on the results of the meta-analysis or other evidence synthesis?

- Did the review authors account for RoB in individual studies when interpreting/discussing the results of the review?

- Did the review authors provide a satisfactory explanation for, and discussion of, any heterogeneity

- If they performed quantitative synthesis did the review authors carry out an adequate investigation of publication bias (small study bias) and discuss its likely impact on the results of the review?

- Did the review authors report any potential sources of conflict of interest, including any funding they received for conducting the review?

3.3. Summary of the Performance of PCR for the Diagnosis of Invasive Aspergillosis

3.4. Other Measures of Diagnostic Performance and Subgroup Analyses

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Marr, K.A.; Carter, R.A.; Boeckh, M.; Martin, P.; Corey, L. Invasive aspergillosis in allogeneic stem cell transplant recipients: Changes in epidemiology and risk factors. Blood 2002, 100, 4358–4366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, R.A. Early diagnosis of fungal infection in immunocompromised patients. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2008, 61 (Suppl. 1), i3–i6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, T.J.; Anaissie, E.J.; Denning, D.W.; Herbrecht, R.; Kontoyiannis, D.P.; Marr, K.A.; Morrison, V.A.; Segal, B.H.; Steinbach, W.J.; Stevens, D.A.; et al. Treatment of aspergillosis: Clinical practice guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2008, 46, 327–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, J.P. Polymerase chain reaction for diagnosing invasive aspergillosis: Getting closer but still a ways to go. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2006, 42, 487–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, P.L.; Bretagne, S.; Caliendo, A.M.; Loeffler, J.; Patterson, T.F.; Slavin, M.; Wingard, J.R. Aspergillus Polymerase Chain Reaction-An Update on Technical Recommendations, Clinical Applications, and Justification for Inclusion in the Second Revision of the EORTC/MSGERC Definitions of Invasive Fungal Disease. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 72 (Suppl. 2), S95–S101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, J.P.; Chen, S.C.; Kauffman, C.A.; Steinbach, W.J.; Baddley, J.W.; Verweij, P.E.; Clancy, C.J.; Wingard, J.R.; Lockhart, S.R.; Groll, A.H.; et al. Revision and Update of the Consensus Definitions of Invasive Fungal Disease from the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer and the Mycoses Study Group Education and Research Consortium. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 71, 1367–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haydour, Q.; Hage, C.A.; Carmona, E.M.; Epelbaum, O.; Evans, S.E.; Gabe, L.M.; Knox, K.S.; Kolls, J.K.; Wengenack, N.L.; Prokop, L.J.; et al. Diagnosis of Fungal Infections. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Supporting American Thoracic Society Practice Guideline. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2019, 16, 1179–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, P.L.; Wingard, J.R.; Bretagne, S.; Löffler, J.; Patterson, T.F.; Slavin, M.A.; Barnes, R.A.; Pappas, P.G.; Donnelly, J.P. Aspergillus Polymerase Chain Reaction: Systematic Review of Evidence for Clinical Use in Comparison with Antigen Testing. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2015, 61, 1293–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumpston, M.; Chandler, J. Chapter IV: Updating a review. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.3; Higgins, J.P.T., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M.L.T., Page, M.J., Welch, V.A., Eds.; Cochrane: London, UK, 2022; Available online: www.training.cochrane.org/handbook (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Pollock, M.; Fernandes, R.M.; Becker, L.A.; Pieper, D.; Hartling, L. Chapter V: Overviews of Reviews. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.3; Higgins, J.P.T., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M.L.T., Page, M.J., Welch, V.A., Eds.; Cochrane: London, UK, 2022; Available online: www.training.cochrane.org/handbook (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- McInnes, M.D.F.; Moher, D.; Thombs, B.D.; McGrath, T.A.; Bossuyt, P.M.; the PRISMA-DTA Group; Clifford, T.; Cohen, J.F.; Deeks, J.J.; Gatsonis, C.; et al. Preferred Reporting Items for a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Diagnostic Test Accuracy Studies: The PRISMA-DTA Statement. JAMA 2018, 319, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascioglu, S.; Rex, J.H.; de Pauw, B.; Bennett, J.E.; Bille, J.; Crokaert, F.; Denning, D.W.; Donnelly, J.P.; Edwards, J.E.; Erjavec, Z.; et al. Defining opportunistic invasive fungal infections in immunocompromised patients with cancer and hematopoietic stem cell transplants: An international consensus. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2002, 34, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pauw, B.; Walsh, T.J.; Donnelly, J.P.; Stevens, D.A.; Edwards, J.E.; Calandra, T.; Pappas, P.G.; Maertens, J.; Lortholary, O.; Kauffman, C.A.; et al. Revised definitions of invasive fungal disease from the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group (EORTC/MSG) Consensus Group. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2008, 46, 1813–1821. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shea, B.J.; Reeves, B.C.; Wells, G.; Thuku, M.; Hamel, C.; Moran, J.; Moher, D.; Tugwell, P.; Welch, V.; Kristjansson, E.; et al. AMSTAR 2: A critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ 2017, 358, j4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brozek, J.L.; Akl, E.A.; Jaeschke, R.; Lang, D.M.; Bossuyt, P.; Glasziou, P.; Helfand, M.; Ueffing, E.; Alonso-Coello, P.; Meerpohl, J.; et al. GRADE Working Group. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations in clinical practice guidelines: Part 2 of 3. The GRADE approach to grading quality of evidence about diagnostic tests and strategies. Allergy 2009, 64, 1109–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schünemann, H.; Brożek, J.; Guyatt, G.; Oxman, A. (Eds.) Handbook for Grading the Quality of Evidence and the Strength of Recommendations Using the GRADE Approach (Updated October 2013); GRADE Working Group: Melbourne, Australia, 2013; Available online: gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/app/handbook/handbook.html (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Mengoli, C.; Cruciani, M.; Barnes, R.A.; Loeffler, J.; Donnelly, J.P. Use of PCR for diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2009, 9, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruciani, M.; Mengoli, C.; Loeffler, J.; Donnelly, P.; Barnes, R.; Jones, B.L.; Klingspor, L.; Morton, O.; Maertens, J. Polymerase chain reaction blood tests for the diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis in immunocompromised people. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 9, CD009551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvanitis, M.; Ziakas, P.D.; Zacharioudakis, I.M.; Zervou, F.N.; Caliendo, A.M.; Mylonakis, E. PCR in diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis: A meta-analysis of diagnostic performance. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2014, 52, 3731–3742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuon, F.F. A systematic literature review on the diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) from bronchoalveolar lavage clinical samples. Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 2007, 24, 89–94. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, W.; Wang, K.; Gao, W.; Su, X.; Qian, Q.; Lu, X.; Song, Y.; Guo, Y.; Shi, Y. Evaluation of PCR on bronchoalveolar lavage fluid for diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis: A bivariate metaanalysis and systematic review. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e28467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avni, T.; Levy, I.; Sprecher, H.; Yahav, D.; Leibovici, L.; Paul, M. Diagnostic accuracy of PCR alone compared to galactomannan in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid for diagnosis of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis: A systematic review. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2012, 50, 3652–3658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvanitis, M.; Anagnostou, T.; Mylonakis, E. Galactomannan and Polymerase Chain Reaction-Based Screening for Invasive Aspergillosis Among High-Risk Hematology Patients: A Diagnostic Meta-analysis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2015, 61, 1263–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heng, S.C.; Morrissey, O.; Chen, S.C.; Thursky, K.; Manser, R.L.; Nation, R.L.; Kong, D.C.; Slavin, M. Utility of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid galactomannan alone or in combination with PCR for the diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis in adult hematology patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2015, 41, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehrnbecher, T.; Robinson, P.D.; Fisher, B.T.; Castagnola, E.; Groll, A.H.; Steinbach, W.J.; Zaoutis, T.E.; Negeri, Z.F.; Beyene, J.; Phillips, B.; et al. Galactomannan, β-D-Glucan, and Polymerase Chain Reaction-Based Assays for the Diagnosis of Invasive Fungal Disease in Pediatric Cancer and Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 63, 1340–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruciani, M.; Mengoli, C.; Barnes, R.; Donnelly, J.P.; Loeffler, J.; Jones, B.L.; Klingspor, L.; Maertens, J.; Morton, C.O.; White, L.P. Polymerase chain reaction blood tests for the diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis in immunocompromised people. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 9, CD009551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruciani, M.; White, P.L.; Mengoli, C.; Löffler, J.; Morton, C.O.; Klingspor, L.; Buchheidt, D.; Maertens, J.; Heinz, W.J.; Rogers, T.R.; et al. Fungal PCR Initiative. The impact of anti-mould prophylaxis on Aspergillus PCR blood testing for the diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2021, 76, 635–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.; Wu, X.; Jiang, G.; Guo, A.; Jin, Z.; Ying, Y.; Lai, J.; Li, W.; Yan, F. Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid polymerase chain reaction for invasive pulmonary aspergillosis among high-risk patients: A diagnostic meta-analysis. BMC Pulm. Med. 2023, 23, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannidis, J.P. Integration of evidence from multiple meta-analyses: A primer on umbrella reviews, treatment networks and multiple treatments meta-analyses. CMAJ 2009, 181, 488–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aromataris, E.; Fernandez, R.; Godfrey, C.M.; Holly, C.; Khalil, H.; Tungpunkom, P. Summarizing systematic reviews: Methodological development, conduct and reporting of an umbrella review approach. Int. J. Evid. Based Health 2015, 13, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, R.A.; White, P.L.; Morton, C.O.; Rogers, T.R.; Cruciani, M.; Loeffler, J.; Donnelly, J.P. Diagnosis of aspergillosis by PCR: Clinical considerations and technical tips. Med. Mycol. 2018, 56 (Suppl. 1), 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, P.L.; Barnes, R.A.; Springer, J.; Klingspor, L.; Cuenca-Estrella, M.; Morton, C.O.; Lagrou, K.; Bretagne, S.; Melchers, W.J.; Mengoli, C.; et al. EAPCRI. Clinical Performance of Aspergillus PCR for Testing Serum and Plasma: A Study by the European Aspergillus PCR Initiative. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2015, 53, 2832–2837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loeffler, J.; Mengoli, C.; Springer, J.; Bretagne, S.; Cuenca-Estrella, M.; Klingspor, L.; Lagrou, K.; Melchers, W.J.; Morton, C.O.; Barnes, R.A.; et al. European Aspergillus PCR Initiative. Analytical Comparison of In Vitro-Spiked Human Serum and Plasma for PCR-Based Detection of Aspergillus fumigatus DNA: A Study by the European Aspergillus PCR Initiative. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2015, 53, 2838–2845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, C.O.; White, P.L.; Barnes, R.A.; Klingspor, L.; Cuenca-Estrella, M.; Lagrou, K.; Bretagne, S.; Melchers, W.; Mengoli, C.; Caliendo, A.M.; et al. EAPCRI. Determining the analytical specificity of PCR-based assays for the diagnosis of IA: What is Aspergillus? Med. Mycol. 2017, 55, 402–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huygens, S.; Dunbar, A.; Buil, J.B.; Klaassen, C.H.W.; Verweij, P.E.; van Dijk, K.; de Jonge, N.; Janssen, J.J.W.M.; van der Velden, W.J.F.M.; Biemond, B.J.; et al. Clinical impact of PCR-based Aspergillus and azole resistance detection in invasive aspergillosis. A prospective multicenter study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2023, 77, ciad141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| First Author, Year [Ref.] | Clinical Setting | Studies Included in the Review (No. Patients and Specimens) | Diagnostic Test | Quality Assessment | Subgroups Analyses | Main Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Index Test | Reference Standard | ||||||

| Tuon, 2007 [20] | Patients at risk of IA (no further information provided). Control groups included healthy adults or patients without risk factors for IA, patients with high risk for IA, and patients with low risk for IA. | Fifteen trials (seven prospective) from 1995 to 2003; 1232 patients (1308 BAL specimens) | PCR on BAL. The preferred method of PCR was the nested-PCR. Four studies, published after 2001, evaluated qPCR. | EORTC/ MSG 2002 | More than 90% of studies met at least 50% of the predefined validity criteria. In eight studies BAL processing was retrospective | Sensitivity was calculated using proven and probable IA. Possible cases not included in the dataset | The overall sensitivity and specificity values of PCR-based techniques in BAL specimens were 79% and 94% |

| Sun, 2011 [21] | Immunocompromised patients or patients at-risk for IA, mostly haematologic malignancies with pulmonary infiltrates. | Seventeen trials (1991 patients, 1296 BAL specimens) from 1993 to 2009. Nine trials had a case−control design, and eight were cohort studies. | PCR on BAL. BAL collection retrospective in 14 trials. | EORTC/MSG 2002 and 2008 | QUADAS-2. The quality of all studies was reported as high (meeting on average 10 of the 14 QUADAS criteria), despite the fact that more than 50% of studies were casecontrol. | Subgroup analyses according to types of PCR, primers (species- vs. genus-specific), study design (cohort vs. case−control), and adherence to EORTC criteria | Six studies used qPCR and the remainder used end-point PCR or semiquantitative PCR. |

| Avni 2012 [22] | Patients at risk of IA (≥80%) | Nineteen trials (1993–2012), including prospective and retrospective cohort studies and case−control studies; 1585 patients at risk of IA | PCR and GM-EIA in BAL. All studies reported on the diagnostic accuracy of PCR in BAL fluid (10 also on GM in BAL fluid) | EORTC/MSG 2002 and 2008. To avoid incorporation bias, patients in whom the microbiological criterion to define IPA was the GM test were excluded from the analysis | QUADAS-2. Nine studies were at high risk of selection bias. Concerns regarding classification, interpretation and applicability of the reference standard were present in 11 studies | Subgroup analysis according to reference standard definition (EORTC criteria 2002 and 2008), use of anti-mold active agents, type of PCR. | Results were affected by the reference standard and by use of antifungal treatment. No statistically significant differences in the accuracy of qPCR, nested, and other PCRs. |

| Heng, 2015 [23] | Haematologic patients at risk of IA | Sixteen trials included in the review, but only six trials (402 patients) reported diagnostic data for BAL GM-EIA and Aspergillus PCR in individual and combination use. Two studies had a case−control design, and four were cohort studies. | GM alone or with PCR on BAL specimens in six trials. Specimen collection: prospective in two studies, retrospective in four. | EORTC/MSG 2002 and 2008. | QUADAS-2. A significant proportion of studies were at high or unclear risk of bias for different domains of the QUADAS-2 list. | Covariates that may lead to false-positive or false-negative results were not analyzed in this meta-analysis due to paucity of data. | Five studies employed real-time PCR technique and one study used nested PCR. The use of BAL GM-EIA with serum GM-EIA or BAL PCR tests increased the sensitivity moderately when a positive result was defined by either assay. Higher rate of false-positive results to GM-EIA in those receiving beta-lactams at the time of bronchoscopy |

| Arvanitis, 2015 [24] | Haematologic patients at risk of IA (in 10 trials adult patients, in one trial paediatric patients) | Thirteen trials (three case−control, ten cohort) for a total of 1670 patients. Tests on whole blood and/or serum as weekly screening. | GM and PCR (no information on PCR methods provided). Specimen collection: prospective in seven studies, retrospective in six. | EORTC/MSG 2002 and 2008 | QUADAS-2. Most of the studies were of fair quality. | Subgroup analyses according to methodological quality, one or two PCR tests, proven and probable and possible cases vs. proven and probable only, with or without incorporation of GM test. | When screening high-risk patients for IA with GM-EIA and PCR tests, the absence of any positive test has a negative predictive value of 100%, whereas the presence of at least two positive results is highly suggestive of an active infection with a positive predictive value of 88%. |

| Lerhbecker, 2016 [25] | Invasive fungal disease in pediatric cancer and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation | Twenty-five studies, GM-EIA (n = 19), BG (n = 3), and PCR (n = 11), and 33 comparisons. Retrospective design in eight trials, prospective in seventeen. | GM-EIA, BG, PCR in blood (in one trial BG also in BAL). | EORTC/MSG 2002 and 2008. In four trials, IFI defined by fungal culture, or clinic and imaging, or histology | QUADAS-2. Several studies judged at high risk of bias, particularly selection bias (e.g., case−control studies) | Diagnostic properties are shown both for when possible IFD was included as a negative control and when patients with possible IFD were excluded from the analysis. | All fungal biomarkers demonstrated highly variable sensitivity, specificity, and positive predictive values. |

| Cruciani, 2019 [26] and 2021 [27] | Immunocompromised patients at risk of IA | Case control excluded; 29 primary studies, corresponding to 34 data sets, published between 2000 and 2018 | PCR in blood or serum; 16 studies also evaluated GM assay, but in 15 trials GM-EIA was part of the reference standard. Thus, to avoid incorporation bias, authors did not compare data of GM-EIA assay to PCR (in one trial, sensitivity and specificity were 100% and 96.7% for qPCR, and 88.2% and 95.8% for GM-EIA). | EORTC/MSG 2002 and 2008 | QUADAS-2, Most studies were at low risk of bias and low concern regarding applicability. | Subgroup analyses in adult and paediatrics patients, study size, reference standard, requirement of one or more positive specimens to define the test positive, use of anti-mold active agents. | PCR shows moderate diagnostic accuracy when used as screening tests for IA in high-risk patient. Importantly the sensitivity of the test confers a high negative predictive value (NPV) such that a negative test allows the diagnosis to be excluded. AMP significantly decreases Aspergillus PCR specificity, without affecting sensitivity. |

| Han, 2023 [28] | Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in at risk patients. Most patients had haematologic malignancies Twelve studies (1147 patients.) included primarily patients. With COPD, solid tumor, autoimmune disease with prolonged use of corticosteroids. | A total of 41 studies (5668 patients), including 6 case−control, 20 retrospective cohort and 15 prospective cohorts. Fourteen studies (2061 patients) provided data about proven Invasive Pulmonary Aspergillosis (IPA) only. | PCR in BAL | EORTC/MSG 2002, 2008 and 2020 | QUADAS-2. High risk of selection bias in case−control studies | Subgroup analyses showed that the underlying diseases and the use of antifungal treatment had a significant impact on the diagnostic sensitivity of BAL fluid PCR. | BAL fluid PCR is a useful diagnostic tool for IPA in immunocompromised patients and is also effective for diagnosing IPA in patients without HM and HSCT/SOT |

| Author, Year [Reference] | AMSTAR-2 DOMAIN | Overall Confidence in the Results of the SR * | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | |||

| Tuon, 2007 [20] | na | low | ||||||||||||||||

| Sun, 2011 [21] | na | high | ||||||||||||||||

| Avni, 2012 [22] | na | high | ||||||||||||||||

| Arvanitis, 2015 [23] | na | high | ||||||||||||||||

| Heng, 2013 [24] | na | high | ||||||||||||||||

| Lehrnbecher, 2016 [25] | na | low | ||||||||||||||||

| Cruciani, 2019 [26] | na | high | ||||||||||||||||

| Han, 2023 [28] | na | high | ||||||||||||||||

| Methodological requirement met | ||||||||||||||||||

| Methodological requirement partially met, or not specified | ||||||||||||||||||

| Methodological requirement unmet | ||||||||||||||||||

| Author, yr | Specimens, No. Studies | Sensitivity (95% CIs) | Specificity (95% CIs) | GRADE (Levels of Evidence) * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tuon, 2007 [20] | BAL, 15 studies | 0.79 § | 0.94 § | Very low (serious RoB, inconsistency) |

| Sun, 2011 [21] | BAL, 17 studies | 0.91 (0.71/0.96) | 0.92 (0.87/0.96) | Very low (serious RoB, inconsistency) |

| Avni, 2012 [22] | BAL, 19 studies | 0.90 (0.77/0.96) | 0.96 (0.93/0.98) | Low (serious RoB) |

| Heng, 2015 [24] | BAL, 6 studies | 0.57 (0.31/0.80) | 0.97 (0.60/1.00) | Very low (serious RoB, imprecision) |

| Han, 2023 [28] | BAL, 41 studies | 0.75 (0.67/0.81) | 0.94 (0.90/0.96) | Low (serious RoB) |

| Arvanitis, 2015 [23] | Blood (WB, serum), 13 studies | 1 **: 0.84 (0.71/0.92) 2+ ***: 0.57 (0.40/0.72) | 0.79 (0.64/0.85) 0.93 (0.87/0.97) | Low (RoB, inconsistency) |

| Lerherbecker, 2016 [25] | Blood (WB, serum, 1 BAL), 11 studies | 0.76 (0.62/0.86) | 0.58 (0.42/0.72) | Low (RoB, inconsistency) |

| Cruciani, 2019 [26] | Blood (WB, serum), 29 studies | 1+ **: 0.79 (0.71/85) 2+ ***: 0.59 (0.40/0.76) | 0.79 (0.69/0.89) 0.95 (0.87/0.98) | Moderate (inconsistency) |

| First Author, Year | Other Measures of Diagnostic Accuracy | Subgroup Analyses |

|---|---|---|

| Tuon, 2007 [20] | LR+, 10.41 (6.40–16.95); LR−, 0.22 (0.14–0.36) | Different control groups were used in the included studies, but pooled sensitivity and specificity data were only provided for the overall analysis. |

| Sun, 2011 [21] | LR+, 11.90 (95% CI, 6.80–20.80); LR−, 0.10 (95% CI, 0.04–0.24). DOR,122 (95% CI, 41–363). | Subgroup analyses showed that the sensitivity was lower with qPCR compared to other types of PCR (mostly nested-PCR and end-point PCR), with species-specific primers compared to genus-specific primers, with cohort design compared to case control, and with degree of adherence to EORTC criteria. |

| Avni 2012 [22] | In the overall analysis, NPV, PPV were 97.7/81.6, and DOR 243 (95% CIs, 81–726). In subgroup of cohort studies strictly adherent to reference standard NPV, PPV 94.6/67.7, and DOR 49 (95% CIs, 24–97) | Specificity was uniformly high. Sensitivity was more variable. In nine cohort studies strictly adherent to the 2002 or 2008 EORTC/MSG criteria, sensitivity and specificity were lower compared to overall analysis (77.2%, 95% CIs, 51.5–87.6%, and 93.5%, 95% CIs, 90.6–95.6%, respectively). Antifungal treatment before bronchoscopy significantly reduced sensitivity (58%, 95% CIs, 44.0–70.9). |

| Arvanitis, 2015 [23] | 1 positive test GM DOR,104 (95% CIs, 37/295) PPV, 61; NPV, 98 PCR DOR, 17 (95% CIs, 7/38) PPV, 38; NPV, 96 GM or PCR, 128 (95% CIs, 37/442) PPV 33; NPV 10 2-positive tests GM DOR, 18 (95% CIs, 7/45) PPV, 59; NPV, 92 PCR DOR, 30 (95% Cis, 13/70) PPV, 67; NPV, 93 GM + PCR, 135 (95% CIs, 38/475) PPV 88; NPV 96 | Single positive test results had modest sensitivity and specificity for screening. The screening approach with the highest sensitivity was the one that used at least one GM-EIA or PCR positive result to define a positive episode, achieving a sensitivity of 99%, significantly higher than any single test. Exclusion of low-quality studies from the overall analysis had marginal impact on effect estimates. |

| Heng, 2015 [24] | LR pos and neg. provided for BAL GM at different cut-off, but not for PCR, At cut-off of 1, GM LR+,16.1 (95% CIs, 6.2/41.8), LR-, 0.26 (95% CIs, 0.14/0.50), DOR, 61 (95% CIs, 21–181) | Five studies employed real-time PCR technique and one study used nested PCR. The use of BAL GM-EIA with serum GM-EIA or BAL-PCR tests increased the sensitivity moderately when a positive result was defined by either assay. Higher rate of false -positive results to GM-EIA in those receiving beta-lactams at the time of bronchoscopy |

| Lerhbecker, 2016 [25] | Screening: GM PPV 0–100; NPV, 85–100 PCR PPV, 20–50; NPV, 60–96 Diagnostic: GM PPV 0–100; NPV, 70–100 PCR PPV, 0–71; NPV, 88–100 | All fungal biomarkers demonstrated highly variable sensitivity, specificity, and positive predictive values. Poor predictive values for blood GM-EIA, BDG and PCR assays, precluding use as screening tools. |

| Cruciani, 2019 [26] and 2021 [27] | At a mean prevalence of 16%, PPV and NPV were: 1 pos. test 42.8% and 95.1% 2 pos. tests 70.3% and 94.4%. DOR: 1-pos. test, 15.1 (95% CIs, 7.9–28.6 ≥2 tests, 34.5 (95% CIs, 8.2–144.2) | Anti-mold prophylaxis significantly decreased Aspergillus PCR specificity (from 86 to 60%), DOR (from 98.06 to 11.80) without affecting sensitivity (83 and 81%). Lower sensitivity and specificity values were found for studies using 2008 criteria compared to those using 2002 criteria: 73.1% (63.2 to 81.1) and 73.3% (60.9 to 82.9) versus 78.7% (70.6 to 85.1) and 82.2% (65.5 to 91.8), respectively (n.s.s.), There was a trend for greater sensitivity and specificity for the in-house assays compared to commercially available kits (0.74 vs. 0.65; 0.84 vs. 0.76, respectively; n.s.s.), Whole blood PCR test had higher sensitivity and lower specificity compared to serum PCR test (n.s.s.). |

| Han, 2023 [28] | DOR-Neg.LR-Pos.LR 44–11.8–0.27 | Sensitivity was lower in prospective, cohort, small group studies and those using revised EORTC/MSG criteria. Antifungal prophylaxis in haematological patients. Reduced sensitivity (from 0.88 to 0.68). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cruciani, M.; White, P.L.; Barnes, R.A.; Loeffler, J.; Donnelly, J.P.; Rogers, T.R.; Heinz, W.J.; Warris, A.; Morton, C.O.; Lengerova, M.; et al. An Overview of Systematic Reviews of Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) for the Diagnosis of Invasive Aspergillosis in Immunocompromised People: A Report of the Fungal PCR Initiative (FPCRI)—An ISHAM Working Group. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 967. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof9100967

Cruciani M, White PL, Barnes RA, Loeffler J, Donnelly JP, Rogers TR, Heinz WJ, Warris A, Morton CO, Lengerova M, et al. An Overview of Systematic Reviews of Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) for the Diagnosis of Invasive Aspergillosis in Immunocompromised People: A Report of the Fungal PCR Initiative (FPCRI)—An ISHAM Working Group. Journal of Fungi. 2023; 9(10):967. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof9100967

Chicago/Turabian StyleCruciani, Mario, P. Lewis White, Rosemary A. Barnes, Juergen Loeffler, J. Peter Donnelly, Thomas R. Rogers, Werner J. Heinz, Adilia Warris, Charles Oliver Morton, Martina Lengerova, and et al. 2023. "An Overview of Systematic Reviews of Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) for the Diagnosis of Invasive Aspergillosis in Immunocompromised People: A Report of the Fungal PCR Initiative (FPCRI)—An ISHAM Working Group" Journal of Fungi 9, no. 10: 967. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof9100967

APA StyleCruciani, M., White, P. L., Barnes, R. A., Loeffler, J., Donnelly, J. P., Rogers, T. R., Heinz, W. J., Warris, A., Morton, C. O., Lengerova, M., Klingspor, L., Sendid, B., & Lockhart, D. E. A. (2023). An Overview of Systematic Reviews of Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) for the Diagnosis of Invasive Aspergillosis in Immunocompromised People: A Report of the Fungal PCR Initiative (FPCRI)—An ISHAM Working Group. Journal of Fungi, 9(10), 967. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof9100967