Abstract

In this paper, we analyze the macrofungi communities of five forest types in Wunvfeng National Forest Park (Jilin, China) by collecting fruiting bodies from 2019–2021. Each forest type had three repeats and covered the main habitats of macrofungi. In addition, we evaluate selected environmental variables and macrofungi communities to relate species composition to potential environmental factors. We collected 1235 specimens belonging to 283 species, 116 genera, and 62 families. We found that Amanitaceae, Boletaceae, Russulaceae, and Tricholomataceae were the most diverse family; further, Amanita, Cortinarius, Lactarius, Russula, and Tricholoma were the dominant genera in the area. The macrofungi diversity showed increasing trends from Pinus koraiensis Siebold et Zuccarini forests to Quercus mongolica Fischer ex Ledebour forests. The cumulative species richness was as follows: Q. mongolica forest A > broadleaf mixed forest B > Q. mongolica, P. koraiensis mix forest D (Q. mongolica was the dominant species) > Q. mongolica and P. koraiensis mix forest C (P. koraiensis was the dominant species) > P. koraiensis forest (E). Ectomycorrhizal fungi were the dominant functional group; they were mainly in forest type A and were influenced by soil moisture content and Q. mongolica content (p < 0.05). The wood-rotting fungus showed richer species diversity than other forest types in broadleaf forests A and B. Overall, we concluded that most fungal communities preferred forest types with a relatively high Q. mongolica content. Therefore, the deliberate protection of Q. mongolica forests proves to be a better strategy for maintaining fungal diversity in Wunvfeng National Forest Park.

1. Introduction

Fungal communities are essential for forest ecosystems and have many functions [1,2]. Ectomycorrhizal fungi (EM) participate in the soil nutrient cycle of forest ecosystems and promote the host plant’s absorption of nutrients, such as nitrogen, phosphorus, and water, thereby maintaining the above-ground primary productivity of the forest ecosystem [3]. Saprotrophic fungi can degrade wood components (i.e., lignin, cellulose, and hemicellulose [4]), and they are considered essential wood-decay-promoting organisms. These functions indicate a crucial role in maintaining the forest ecosystem’s stability [5].

Many biotic and abiotic factors can affect the diversity and composition of fungal communities [6,7]. The composition of EM is strongly influenced by the soil’s nitrogen content [8,9], pH [10], temperature and moisture [11,12], the species composition of the host trees [13,14], and by the seasons [15]. Fungal communities living on the wood are closely dependent upon environmental factors, such as the amount, diameter, and stage of wood decomposition [16], wood chemistry [17], age [18], and tree species [19]. Factors influencing terricolous saprotrophic communities include litter quantity and pH [20], soil P content [21,22], plant species [23,24], and temperature [25]. The processes of natural or human-induced change in the vegetation composition of forests are also important drivers of fungal diversity [26,27,28], as they are associated with significant changes in litter and soil quality in the long term [29,30,31].

Our study sites are all within the Wunvfeng National Forest Park in the southeastern mountainous region of the Jilin Province, China. The reserve was established in 1992 and is part of the Changbai Mountain system. The original vegetation included Quercus mongolica Fischer ex Ledebour forests and mixed broadleaf forests, which changed when Pinus koraiensis Siebold et Zuccarini was planted in the 1980s [32]. Currently, the vegetation composition includes a P. koraiensis forest, and P. koraiensis–Q. mongolica mixed forests provide a unique opportunity to investigate the fungal communities of different forest types under the same climatic conditions. Usually, Pinus species are dependent upon macrofungi in symbiotic associations, which are essential for their growth and survival [33] because symbiotic associations facilitate the trees’ uptake of water and nutrients [34,35]. Some specific fungal species may be found in relatively stable Pinus forests. Thus, understanding the distribution characteristics of fungal communities in planted and native forests can provide better strategies for fungal diversity conservation, especially for the deliberate conservation of forest types that host a more significant number of fungal species. In this context, we conducted a three-year survey of macrofungi in different vegetation types in Wunvfeng National Forest Park. We study the relationship between selected environmental factors and community composition. We aim to investigate whether fungal communities differ among the five forest types and whether native forests dominated by Q. mongolica are potentially associated with fungal communities.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area Description

Our study site, Wunvfeng National Forest Park, covers an area of 6867 hm2 [36] and is situated in Ji’an City in the extreme southeast part of the Jilin Province, Northeast China (126°2′21″–126°17′57″ E, 41°11′37″–41°21′40″ N). The area is characterized by a temperate continental monsoon climate with a mean annual precipitation of 950 mm with peaks from June–August and a mean annual air temperature of 6.5 °C [36]. The forest cover is 95%, and the dominant tree species is Q. mongolica. P. koraiensis was planted as a non-native tree species in 1980. At present, it has formed stable forest communities. Dark-brown soil [37] is the most frequent soil type. The fundamental geomorphological units belong to the Changbai Mountains, ranging in altitude from 500–1500 m [38].

2.2. Fruiting Body Sampling

We designated five following forest types: A, B, C, D, and E. Three 50 m × 50 m sampling plots with at least 500 m distance between them were located within each forest type (pictures of each forest type are provided in Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Sampling plot distribution and forest types in Wunvfeng National Forest Park. Note: Sampling plot distribution (A); Plots A1, A2, A3 = Q. mongolica forest (B); Plots B1, B2, B3 = Broad-leaved forest (C); Plots C1, C2, C3 = P. koraiensis and Q. mongolica mixed forest (P. koraiensis is the dominant species (D)); Plots D1, D2, D3 = P. koraiensis and Q. mongolica mixed forest, (Q. mongolica is the dominant species (E)); Plots E1, E2, E3 = P. koraiensis forest (F).

Quercus mongolica site (A): Old-growth Q. mongolica forests with the original habitat, and no fallen or standing deadwood has been removed. There are 275 Q. mongolica with a coverage rate of 96.15%.

Broad-leaved forest site (B): Mixed broadleaved forest (uneven-aged), with Q. mongolica, Tilia amurensis Rupr., Fraxinus mandshurica Rupr., Acer palmatum Thunb., Juglans regia L., close to nature managed. There are 158 Q. mongolica with a coverage rate of 48.46%.

Pinus koraiensis and Quercus mongolica mixed sites (C): 30–50-year-old P. koraiensis forest, close to nature managed, and naturally grown Q. mongolica. P. koraiensis was artificially grown and is the dominant species. There are 42 Q. mongolica with a coverage rate of 18.03%.

Quercus mongolica and Pinus koraiensis mixed sites (D): 30–60-year-old Q. mongolica forests, close to nature managed, and artificially grown P. koraiensis. Q. mongolica is the dominant species. There are 183 Q. mongolica with a coverage rate of 74.69%.

Pinus. koraiensis sites (E): Single species; 40-year-old P. koraiensis forests planted in 1980, close to nature managed, no fallen trees removed. There are zero Q. mongolica with a coverage rate of 0%.

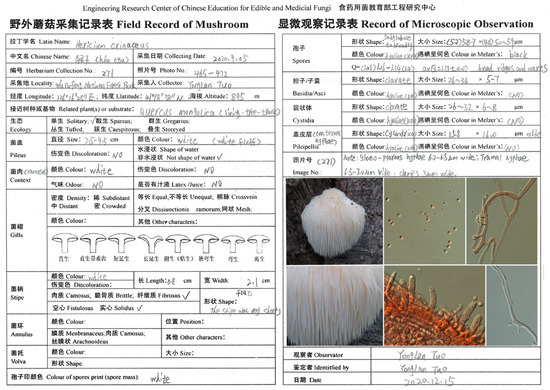

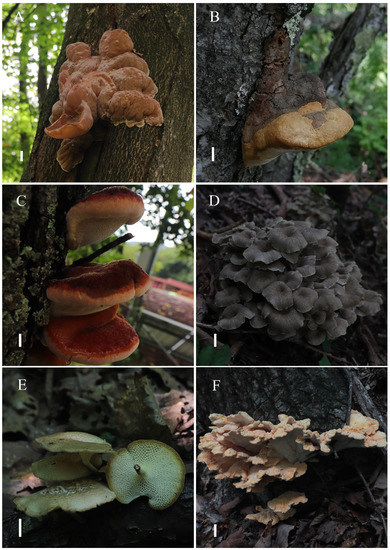

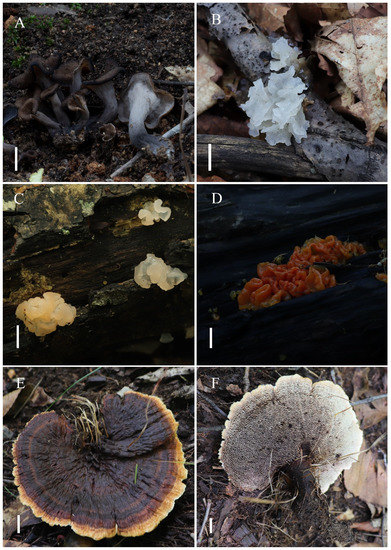

We collected samples 20–25 times per month from June to October 2019–2021. We randomly acquired macrofungi from each plot. We photographed the specimens in the field using a Canon EOS 800D digital camera and recorded fresh morphological characteristics and ecological characteristics (Figure 2). We selected the context or stipe tissue (1–2 g) of the same specimen when it was fresh and stored it in a sealed bag with silica gel for DNA extraction; we dried them in an oven (45–50 °C) and placed them in specimen boxes. We then took a morphotype of each specimen to the laboratory and used it for morphological species identification.

Figure 2.

Field record of mushrooms and microscopic characteristic observation.

2.3. Soil Sampling, Analysis and Environmental Data Collection

We collected soil samples four times per month during July–September 2020. After cleaning and removing plant material and debris from the surface, we collected individual soil samples from the center and 4 corners in 15 plots using an auger (5 cm radius, 5 cm depth). We mixed the soil samples from the same plots well and placed them in sealed bags. After removing impurities, we enclosed the fresh samples (20 g) from each clod in an aluminum box. We dried the samples to a constant weight in an oven at 105 °C to measure water content (SWC); we used natural air-dried composite samples (200 g) for each plot to analyze for pH, organic matter (SOM), available phosphorus (P), effective nitrogen (N), and available potassium (K) using the method described by Xing et al. [39]. Finally, we averaged the data from three plots of the five fore for subsequent analysis.

We obtained the temperature and relative humidity of the air and soil temperature from July–September 2020 from meteorological monitoring sites in the forest park. The tested results for the soil are included in Table 1.

Table 1.

Quercus mongolica content and selected environmental variables properties in five forest types.

2.4. Species Identification

We identified the macrofungi using morphological observations methods. We used molecular methods for the species that were morphologically difficult to identify. We measured different microscopic structures of taxonomic importance (e.g., spores, basidia, cystidia) [40]. We examined the morphological features of the fruiting bodies using appropriate monographs, including by Li et al. [41] and Liu et al. [42], to identify each macrofungi specimens. The specimens are currently housed in the Herbarium of Mycology of Jilin Agricultural University (HMJAU), Changchun, China.

Molecular identification involved sequencing the internal transcribed spacer (ITS). For this, we extracted the DNA of the macrofungi using a NuClean Plant Genomic DNA Kit (Cowin Biosciences, Taizhou, China), following the manufacturer’s instructions. We conducted final elutions in a total volume of 50 μL. We showed a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with the primer pairs ITS-1F and ITS-4 [43]; finally, we sequenced the PCR products using the Sanger method. We conducted the PCR in 25 μL reactions consisting of 2 μL genomic DNA, 0.5 μL Taq, and one μL upstream and downstream primers, respectively. We used 14.5 μL ddH2O, five μL 5 × PCR buffer, and 1 µL dNTP in the PCR reactions that we ran under the following conditions: 95 °C for 3 min, followed by 35 cycles of 94 °C for 40 s, 55 °C for 45 s, 72 °C for 1.5 min, and a final extension step at 72 °C for 6 min before storage at 4 °C We purified the PCR products and sequenced them at Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). We performed molecular identification via BLAST comparisons. Species with >98% sequence similarity were also identified with morphological characteristics. GenBank accession numbers obtained are provided in Appendix B.

We identified ecological functions (ectomycorrhizal fungi; soil saprotroph; wood-decaying fungi; litter saprotroph; dung saprotroph; endophyte-insect pathogen) at the genera level using a FUNGuild (available online: http://www.funguild.org (accessed on 18 November 2021) search; these can be found in Appendix B. We classified macrofungi into eight types (agarics; large ascomycetes; boletes; polyporoid fungi; coral fungi; gasteoid fungi; jelly fungi; hydnaceous fungi, and cantharelloid fungi) according to the method of Li et al. [41]. The fungal nomenclature follows the Index Fungorum (available online: http://www.indexfungorum.org (accessed on 15 November 2021)). Setting scientific names at all taxonomic ranks in italics facilitates quick recognition in scientific papers [44].

2.5. Statistical Analysis

We used three alpha diversity indices to analyze the community composition of the macrofungi. The Menhinick richness index (R) reflected the species richness of the community. The Shannon index (D) reflected the diversity of the community species. Pielou’s evenness index (E) reflected the distribution of the number of individuals in each species. The diversity index formulae were as follows:

where Pi is the proportion of species i to the total number of individuals of all species in the plot; ln is the natural logarithm; S is the total number of species in the plot; and N is the total number of individuals observed in the plot.

D = −∑Pi ln (Pi)

E = H’/lnS; H’= −∑Pi ln (Pi)

We analyzed the relationships between ectomycorrhizal fungi communities and selected variables using the canonical correlation analysis (CCA) from Canoco 5.0 [45]. We first used detrended correspondence analysis (DCA) to determine the appropriate model for direct gradient analysis. The results indicated that a unimodal model (gradient lengths > 3 standard units) would best fit our study data; we utilized CCA. Furthermore, we tested explanatory variables using the Monte Carlo permutation test provided by Canoco 5.0 software (with 999 randomizations). The species data matrix for the CCA analysis was based on the presence–absence data of ectomycorrhizal fungi species in each forest type (three-year accumulation of the five forest types).

We used Origin 9.0 software to construct species stacked histograms at the genera level [46] to compare community compositions of the macrofungi species in the five forests and provide the relative proportion of macrofungi species richness (data include the number of species at the genera level in each forest type). Additionally, we generated pie charts, Venn diagrams, and species accumulation curves using Hiplot (available online: https://hiplot.com.cn/basic/venn (accessed on 20 October 2021)). The pie chart data were derived from the number of macrofungi types. The Venn diagram data included the species in each forest type. The accumulation curve data consisted of the cumulative number of species per collection.

3. Results

3.1. Species Richness

We collected 1235 specimens from 5 forest types, 940 (76.11%) of which we identified at the species level, and we classified these into 283 fungal species. We identified 244 species based on morphology and 39 species using morphology and molecular methods (Appendix B). The unidentified sporocarps were not part of our further analysis. We classified the macrofungi species into 116 genera, 62 families, 18 orders, and 2 phyla. Basidiomycota was the dominant phylum, divided into 12 orders, 50 families, 102 genera, and 265 species. Ascomycota was divided into 6 orders, 12 families, 14 genera, and 18 species. The Russulaceae was the most diverse family with 36 different species, followed by Tricholomataceae (21 species), Boletaceae (19 species), and Amanitaceae (16 species). Together, these accounted for 32.51% of the total collected species. The most abundant genera were Amanita, Cortinarius, Lactarius, and Russula. The Agaricales were the most prevalent order in the five forest types (59.36%). In terms of the trophic groups, most of the species were ectomycorrhizal fungi (47%), followed by wood-decaying fungi (20.14%) and soil saprotrophs (18.37%).

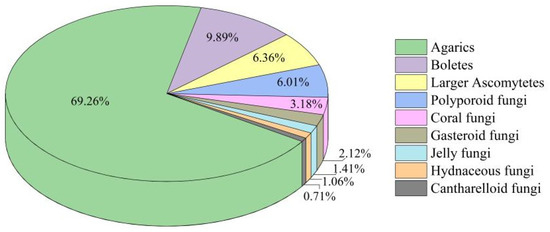

3.2. Macrofungal Types

The most significant genera of Agarics accounted for 69.26% of the identified species, followed by boletes, larger ascomytetes, and polyporoid fungi, accounting for 9.89%, 6.36%, and 6.01% of the identified species, respectively. In contrast, hydnaceous and cantharelloid fungi were less abundant, accounting for 1.06% and 0.71%, respectively (see Figure 3). For more detailed information, see Appendix B. For images of some species, see Appendix A.

Figure 3.

The proportion of different macrofungal types.

3.3. Analysis of Dominant Families and Genera

Among the identified species, there were 9 dominant families (number of species ≥10 species) of macrofungi (Table 2). The Russulaceae was the most diverse family. In addition, 53 families contained less than 10 species, accounting for 85.48% of the families and 48.06% of the identified species (Appendix B).

Table 2.

Dominant families (≥10 species) of macrofungi in Wunvfeng National Forest Park.

Among the identified species, there were 15 dominant genera (number of species ≥ 5 species) of macrofungi (Table 3). The Amanita, Lactarius, and Russula were the most diverse genera. In addition, 34 genera contained 2–4 species, accounting for 29.31% of the genera and 29.68% of the identified species; 67 of the genera contained only 1 species, accounting for 57.76% of the genera and 23.67% of the identified species (Appendix B).

Table 3.

Dominant genera (≥5 species) of macrofungi in Wunvfeng National Forest Park.

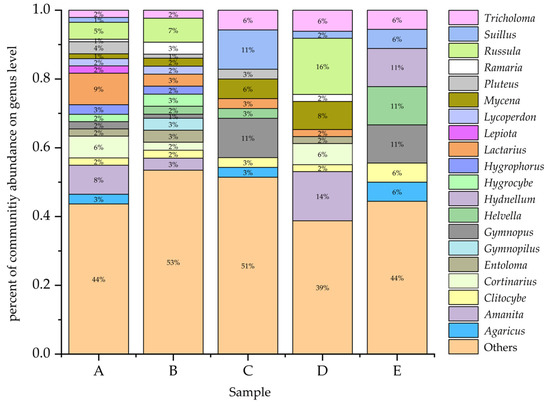

3.4. Forest Type and Species Composition

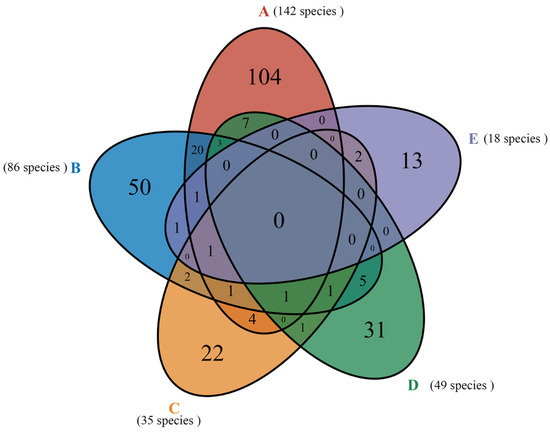

The community of macrofungi was different among the five forest types (Figure 4). The species richness increased from E (18 species, 6.36%) < C (35 species, 12.37%) < D (49 species, 17.31%) < B (86 species, 30.39%) < A (142 species, 50.18%). The Lactarius (13 species), Amanita (12 species), Coprinellus (10 species), and Russula (7 species) were the most species-rich genera in forest type A. The Russula (6 species) and Gymnopilus (4 species) were the most species-rich genera in forest type B. The Gymnopus (4 species) and Suillus (4 species) were the most species-rich genera in forest type C. The Russula (8 species), Amanita (7 species), and Mycena (4 species) were the most species-rich genera in forest type D. Finally, the Gymnopus (2 species), Helvella (2 species), and Hydnellum (2 species) were the relatively abundant genera in forest type E. More detailed information is shown in Appendix B.

Figure 4.

The relative proportions of macrofungi taxa at the genera level in five forest types. (A): Q. mongolica forest; (B): Broad-leaved forest; (C): P. koraiensis and Q. mongolica mixed forest with P. koraiensis being the dominant species; (D): P. koraiensis and Q. mongolica mixed forest with Q. mongolica being the dominant species; (E): Pinus koraiensis forest.

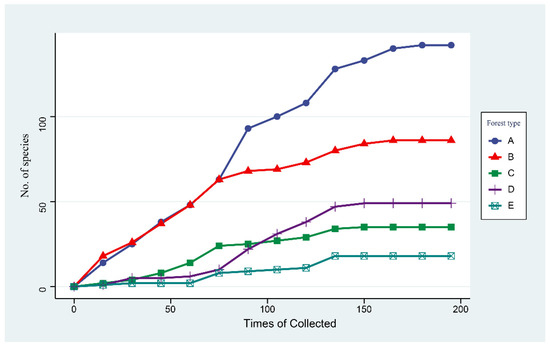

3.5. Cumulative Abundance of Macrofungi in Five Forest Types

The accumulation curves for the species identified in the five forests show a steady increase with more samplings (Figure 5). We reached saturation of macrofungi richness after 150 surveys. The species accumulation curves of A (Q. mongolica forest) and B (broad-leaved forest) showed relatively steep upward slopes and produced higher macrofungi abundance values than the other forests. Nevertheless, forest type A (Q. mongolica forest) obtained the highest macrofungi diversity values.

Figure 5.

Sample-based rarefaction curves (n = 195 observations per forest type within 3 years). (A): Q. mongolica forest; (B): broad-leaved forest; (C): P. koraiensis and Q. mongolica mixed forest with P. koraiensis being the dominant species; (D): P. koraiensis and Q. mongolica mixed forest with Q. mongolica being the dominant species; (E): P. koraiensis forest.

Two genera (Clitocybe and Tricholoma) were shared in five forest types, but no species were shared. The unique species (found only in 1 forest) increased from E < C < D < B < A and consisted of 13, 22, 31, 50, and 104 fungal species, respectively (Figure 6). Forest type A shared 27 species with B, 7 species with C, 11 species with D, and 2 species with E. Forest type B shared six species with C, eleven species with D, and three species with E. Forest type C shared three species with D and three species with E. The Gymnopus densilamellatus Antonín, Ryoo & Ka, and Suillus grevillei (Klotzsch) Singer only appeared in E and C. The S. luteus (L.) Roussel only appeared in D and C; Helvella crispa (Scop.) Fr. only appeared in B and E. The Amanita oberwinklerana Zhu L. Yang & Yoshim., Amanita orsonii Ash. Kumar & T.N. Lakh., Amanita virosa Bertill., Boletus edulis Bull., Phellinus pomaceus (Pers.) Maire, Russula paludosa Britzelm., and Tricholoma sejunctum (Sowerby) Quél., only appeared in A and D. The Agaricus moelleri Wasser, Gymnopus dryophilus (Bull.) Murrill, Pluteus leoninus (Schaeff.) P. Kumm., and Rhodocollybia butyracea (Bull.) Lennox only appeared in A and C.

Figure 6.

A Venn diagram of 283 fungal species shows shared and unique fungi for the five forest types. The numbers in parentheses are the values of all observed fungi in each forest type studied (cumulative species richness).

The species richness increased from E < C < D < B < A (Table 4). Broad-leaved forests A and B, with the highest richness indices of 7.4023 and 5.4832, respectively, accounted for 80.57% of the total species. Among them, 142 species were found in forest type A, accounting for 50.18% of the total species. This indicates that the broadleaf forest was the main habitat of macrofungi in the area, especially regarding the Q. mongolica forest. Mixed forests C and D, with richness indices of 2.8296 and 4.6509, contained 84 species, accounting for 29.68% of the total species. However, we found that the species abundance was higher in forest type D (49 species) than in forest type C (35 species), indicating that macrofungal species are associated with Q. mongolica. In P. koraiensis forest E, with the smallest species richness index of 2.286, we only found 18 species, accounting for 6.36% of the total species. This indicates that P. koraiensis forests can only provide habitats for a few fungal species.

Table 4.

Diversity indices of macrofungi in five forest types.

3.6. Functional Diversity of Macrofungal Communities

The main functional groups were ectomycorrhizal fungi (EM), wood-decaying fungi (WS), and soil saprotroph (SS). The EM (133 species, 47.0%), WS (57 species, 20.14%), SS (52 species, 18.37%), and LS (38 species, 13.43%) increased from coniferous forest (E) < mixed coniferous forest (C, D) < broadleaf forest (A, B). EM fungi were most abundant in forest type A (Table 5). The highest content of EM fungi was Amanita, Cortinarius, Lactarius, and Russula. The most common WS were Pleurotus and Polyporus. The highest occurrence of SS was Agaricus, Entoloma, and Hygrocybe. The LS, Clitocybe, Gymnopus, Mycena, and Pluteus, showed the highest occurrence.

Table 5.

Cumulative species richness of functional groups in five forest types.

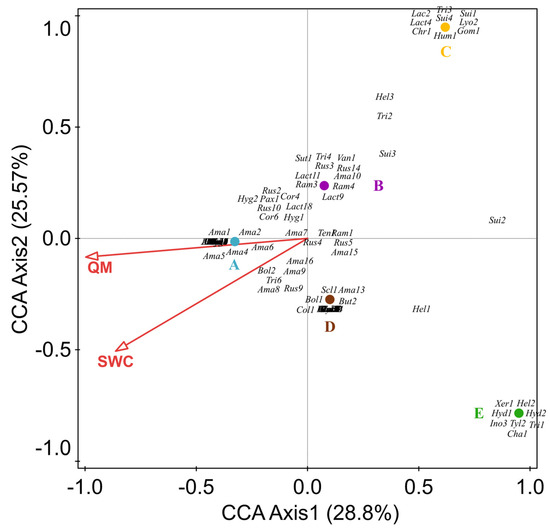

3.7. CCA Analysis of Macrofungal Communities and Selected Environmental Factors

We performed a canonical correspondence analysis (CCA) for the 130 ectomycorrhizal fungi (EM) species recorded in the 5 forest types. The variables included Q. mongolica content, effective soil nitrogen, soil available phosphorus, soil available potassium, soil organic matter, soil pH, soil temperature, air temperature, soil water content, effective soil nitrogen, and air relative humidity. The CCA results show that all samples were roughly separated into five groups according to their corresponding locations. Eigenvalue axis 1 (0.8963) is higher than axis 2 (0.7955), with a cumulative contribution of 28.8% and 25.57%, respectively. Of all the variables, the Q. mongolica content and soil moisture content were the most significant factors influencing the EM fungi. Many EM fungi (e.g., Amanita, Cortinarius, Lactarius) positively correlate with Q. mongolica and soil water (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Canonical correspondence analysis (CCA) of selected variables and the ectomycorrhizal fungi species (dominant group). All displayed variables passed the most significant test (p < 0.05); QM: the number of Q. mongolica; SWC: soil water content; (A): Q. mongolica forest; (B): Broad–leaved forest; (C): P. koraiensis and Q. mongolica mixed forest with P. koraiensis being the dominant species; (D): P. koraiensis and Q. mongolica mixed forest with Q. mongolica being the dominant species; (E): P. koraiensis forest. Letters are composed of the first three–letter abbreviations of the scientific name of the species and a number, and the corresponding names are provided in Appendix C. Some species’ labels are overlapping. See Appendix C.

4. Discussion

This study is the first systematic survey of macrofungal diversity in Wunvfeng National Forest Park, Ji’an, China. We divided the forests into five main types: Q. mongolica forests (A), mixed broad-leaved forests (B), artificial P. koraiensis forests (E), and mixed forests (C, D). This enabled us to analyze the composition of macrofungi according to the relative content change of Q. mongolica in different forest types. The results show differences in species richness and diversity among forest types with different relative contents of Q. mongolica. The species richness increases with the relative content of Q. mongolica. Forest types with a high cover of Q. mongolica may provide a stable environment for the growth of macrofungi [47]. More importantly, Quercus is the main host plant of EM fungi [48], such as Lactarius [49,50], Amanita [51], Russula [52], and Cortinarius [53]. Our results reveal that the EM fungi are mainly distributed in the Q. mongolica forest. Most EM fungi had a significant positive correlation with Q. mongolica content (Figure 7), especially Amanita, Cortinarius, and Lactarius. In addition, we found that 11 species are shared in forest types A and D (e.g., Amanita ibotengutake T. Oda, C. Tanaka & Tsuda, Amanita oberwinklerana Zhu L. Yang & Yoshim, Amanita orsonii Ash. Kumar & T.N. Lakh., and Amanita virosa Bertill). However, they are not found in the P. koraiensis forest. These species may be associated with Q. mongolica (Figure 7, Ama7, Ama8, Ama9, Ama16), because the macrofungal communities change accordingly with the forest’s succession [54]. Therefore, these macrofungi shared in forest types D and A are likely to be in the early stages that develop from spore banks present in the soil [55].

The species richness of P. koraiensis forests is the lowest in our study. We only found 18 species. Theoretically, species richness may be similar between Q. mongolica and P. koraiensis forests because the EM fungi in temperate forests are significantly associated with Quercus and Pinus [56]. However, we only observed ten species of EM fungi in P. koraiensis forest (E) (e.g., Hydnellum aurantiacum (Batsch) P. Karst., Hydnellum peckii Banker, and Tricholoma matsutake (S. Ito & S. Imai) Singer). Our results differ from those of Gao [57], who found more EM fungi in P. koraiensis forests (aged < 150 years). On the one hand, EM fungi may need more time to form a stable symbiosis with the host plants [58]; on the other hand, the exotic trees have difficulty developing long-lasting symbiotic relationships with local EM fungi [59].

In our study, wood-dwelling fungi (57 species) are also a critical taxon that is mainly distributed in the Q. mongolica and mixed broad-leaved forests and grows on larger diameter Q. mongolica fallen wood (e.g., Armillaria gallica Marxm. & Romagn. and Neolentinus cyathiformis (Schaeff.) Della Magg. & Trassin). The wood-dwelling macrofungi may be related to forest type, as they tend to favor specific forest types under similar climatic conditions. In general, these combinations are determined by fungi closely related to the dominant tree, mainly because their enzymes have adapted to wood with different chemical and physical properties [60]. Another reason may be that large logs that provide a larger surface area have a greater chance of being colonized by fungal spores and mycelium than small logs. Species that produce large fruiting bodies also require more space [61]. Furthermore, we only found a few fallen trees in the Q. mongolica and mixed broadleaved forests; we found no fallen trees in the P. koraiensis forest, which is another factor that might affect fungal assemblage. The amount of deadwood also affects the macrofungal assemblage, which previous authors highlighted as the most crucial microhabitat in the forest [62,63]. The diversity of woody macrofungi strongly depends on the presence and amount of deadwood [64,65].

Saprophytic soil fungi (52 species) rely mainly on the decomposition of soil organic matter for nutrients, and they tend to prefer specific forest types under similar climatic conditions. Generally, the deciduous leaves of broad-leaved trees are more conducive to soil organic matter accumulation than coniferous forests [66]. The forest types with high soil organic matter have more opportunities to be colonized by fungal spores and mycelium [67]. Moreover, we only found thicker deciduous leaves in the Q. mongolica and mixed broad-leaved forests, affecting the grass rot fungal assemblage because litter saprotroph fungi strongly depend on deciduous leaves’ presence and volume [68].

The composition of fungi is also influenced and constrained by soil environmental variables [69,70]. These include soil moisture [71], soil pH [72], soil nutrients [73] and soil total C [74]. We analyzed the correlation between the main functional groups (ectomycorrhizal fungi) and selected environmental factors. The results showed that most ectomycorrhizal fungi are closely related to soil water content, especially Amanita, Cortinarius, Lactarius, and Russula (Figure 7). This result suggests that specific fungal communities respond to soil parameters differently [75,76,77]. Previous studies have shown that soil moisture is one factor that regulates the composition of the ectomycorrhizal fungi community [78,79,80,81]. Hydraulic lift contributes to maintaining EM fungi roots’ integrity and viability of extraradical hyphae [82]; further, EM fungi take up water and organic and inorganic nutrients from the soil via the extraradical hyphae and translocate these to colonized tree roots, receiving carbohydrates from the host in return [83]. This may be an important reason why most ectomycorrhizal fungi prefer forest types with relatively high soil water content.

This study with three years of species data is a small contribution that allows us to understand the distribution of fungal species in forest types with the different covers of Q. mongolica. The Wunvfeng National Forest Park has a strict protection policy for animals and plants, including soil protection. Thus, our soil data (with permission) are from July to September 2020 only. Nevertheless, our results illuminate the potential links between community composition and environmental factors because the July–September 2020 species data include almost all our species.

5. Conclusions

The Q. mongolica forests we analyzed are rich in macrofungal species. Although our data are based on only three years of sampling, we conclude that, as Q. mongolica increases in the forest, the abundance and diversity of macrofungal taxa also increase. We also observed that most EM species favored forest types with high Q. mongolica content (e.g., Amanita, Cortinarius, Lactarius, and Russula), indicating that some EM fungal communities are closely associated with Q. mongolica. We call for further studies to support this claim. In addition, we have only found Tricholoma matsutake (S. Ito & S. Imai) Singer in P. koraiensis forests, which is classified as an endangered species and considered an ectomycorrhizal fungus that is closely associated with Pinus trees. Therefore, according to our research, maintaining P. koraiensis forests is beneficial for conserving endangered species. However, deliberate conservation of Q. mongolica forests would be more useful for maintaining the diversity of macrofungal communities. Whether P. koraiensis affects other fungal species will need to be monitored over 3–5 years.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.T.; experimental design and methodology, Y.T. and B.Z.; performance of practical work, Y.T., J.H., Y.W. and G.Z.; statistical analyses, Y.T., N.R., Z.Z. and Z.Q.; validation, B.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.T.; writing—review and editing, B.Z.; supervision, B.Z.; project administration, B.Z.; funding acquisition, B.Z. and Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

We would like to express our gratitude to all the people who gave help to this study. This research supported the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31970020); the Key Project on R&D of Ministry of Science and Technology (No. 2018YFE0107800); Jilin Province Science and Technology Development Plan Project (20190201026JC, 20190201256JC); The National Key R&D of Ministry of Science and Technology(2019YFD1001905-33); The Scientific Production and Construction Crops (No. 2021AB004).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors state no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Photos of Some Species

Larger Ascomycetes.

Figure A1.

(A) Leotia lubrica; (B) Helvella elastica; (C) Sowerbyella rhenana; (D) Spathularia flavida; (E) Ophiocordyceps nutans; (F) Xylaria hypoxylon; Bars: 1 cm.

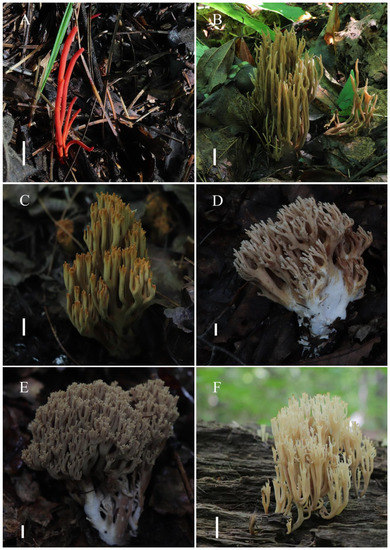

Coral fungi.

Figure A2.

(A) Clavulinopsis sulcata; (B) Ramaria stricta; (C) R. cokeri; (D) R. sanguinipes; (E) R. fennica; (F) Artomyces pyxidatus; Bars: 1 cm.

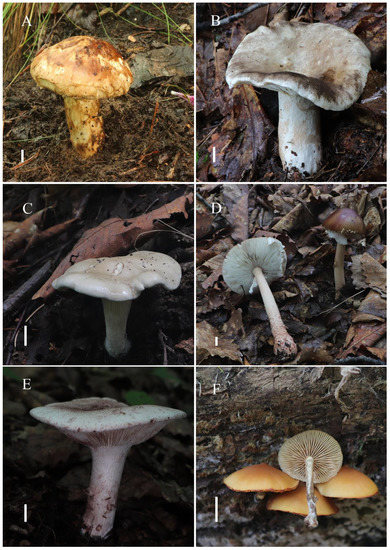

Agarics.

Figure A3.

(A) Tricholoma matsutake; (B) Russula furcata; (C) Clitocybe fasciculata; (D) Amanita orsonii; (E) Hygrophorus russula; (F) Galerina marginata; Bars: 1 cm.

Boletes.

Figure A4.

(A) Pulveroboletus macrosporus; (B) Tylopilus felleus; (C) Boletus edulis; (D) Chalciporus piperatus; (E) Butyriboletus roseoflavus; (F) Suillus grevillei; Bars: 1 cm.

Polyporoid fungi.

Figure A5.

(A) Gloeostereum incarnatum; (B) Phellinus pomaceus; (C) Inonotus hispidus; (D) Polyporus umbellatus; (E) Lentinus arcularius; (F) Laetiporus sulphureus; Bars: 1 cm.

Jelly fungi and Hydnaceous fungi.

Figure A6.

(A) Craterellus cornucopioides; (B) Tremella fuciformis; (C) Dacrymyces yunnanensis; (D) D. chrysospermus; (E,F) Hydnellum aurantiacum; Bars: 1 cm.

Appendix B. Macrofungi were collected in five forest types of Wunvfeng National Forest Park

| Species | Family | Genera | A | B | C | D | E | F | N | ML | Categories | SN | GenBank Number |

| Agaricus arvensis Schaeff. | Agaricaceae | Agaricus | √ | 4 | SS | Agarics | HMJAU60588 | ||||||

| Agaricus dulcidulus Schulzer | Agaricaceae | Agaricus | √ | 2 | SS | Agarics | HMJAU60589 | ||||||

| Agaricus moelleri Wasser | Agaricaceae | Agaricus | √ | √ | 3 | SS | Agarics | HMJAU60590 | |||||

| Agaricus placomyces Peck | Agaricaceae | Agaricus | √ | 1 | SS | Agarics | HMJAU60591 | ||||||

| Agaricus semotus Fr. | Agaricaceae | Agaricus | √ | 2 | SS | Agarics | HMJAU60592 | ||||||

| Agaricus subrufescens Peck | Agaricaceae | Agaricus | √ | 1 | SS | Agarics | HMJAU60593 | ||||||

| Agrocybe arvalis (Fr.) Singer | Strophariaceae | Agrocybe | √ | 3 | SS | Agarics | HMJAU60594 | ||||||

| Agrocybe erebia (Fr.) Kühner ex Singe | Strophariaceae | Agrocybe | √ | 2 | SS | Agarics | HMJAU60595 | ||||||

| Agrocybe praecox (Pers.) Fayod | Strophariaceae | Agrocybe | √ | √ | √ | 6 | SS | Agarics | HMJAU60596 | ||||

| Amanita altipes Zhu L. Yang, M. Weiss & Oberw. | Amanitaceae | Amanita | √ | 1 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60597 | ||||||

| Amanita chepangiana Tulloss & Bhandary | Amanitaceae | Amanita | √ | 1 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60598 | ||||||

| Amanita excelsa (Fr.) Bertill. | Amanitaceae | Amanita | √ | 1 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60599 | ||||||

| Amanita flavipes S. Imai | Amanitaceae | Amanita | √ | 2 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60600 | ||||||

| Amanita fuliginea Hongo | Amanitaceae | Amanita | √ | 2 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60601 | ||||||

| Amanita hemibapha (Berk. & Broome) Sacc. | Amanitaceae | Amanita | √ | 2 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60602 | ||||||

| Amanita ibotengutake T. Oda, C. Tanaka & Tsuda | Amanitaceae | Amanita | √ | √ | √ | 6 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60603 | ||||

| Amanita oberwinklerana Zhu L. Yang & Yoshim. | Amanitaceae | Amanita | √ | √ | 3 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60604 | |||||

| Amanita orsonii Ash. Kumar & T.N. Lakh. | Amanitaceae | Amanita | √ | √ | 5 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60605 | |||||

| Amanita pallidocarnea (Höhn.) Boedijn | Amanitaceae | Amanita | √ | 2 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60606 | ||||||

| Amanita pallidorosea P. Zhang & Zhu L. Yang | Amanitaceae | Amanita | √ | 2 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60607 | ||||||

| Amanita rimosa P. Zhang & Zhu L. | Amanitaceae | Amanita | √ | 1 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60608 | ||||||

| Amanita rubescens Pers. | Amanitaceae | Amanita | √ | 2 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60609 | ||||||

| Amanita subglobosa Zhu L. Yang | Amanitaceae | Amanita | √ | 1 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60610 | ||||||

| Amanita vaginata (Bull.) Lam. | Amanitaceae | Amanita | √ | √ | 3 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60611 | |||||

| Amanita virosa Secr. | Amanitaceae | Amanita | √ | √ | 4 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60612 | |||||

| Ampulloclitocybe clavipes (Pers.) Redhead, Lutzoni, Moncalvo & Vilgalys | Hygrophoraceae | Ampulloclitocybe | √ | 4 | LS | Agarics | HMJAU60613 | ||||||

| Armillaria gallica Marxm. & Romagn. | Physalacriaceae | Armillaria | √ | √ | √ | 15 | WS | Agarics | HMJAU60614 | OL891486 | |||

| Armillaria mellea (Vahl) P. Kumm. | Physalacriaceae | Armillaria | √ | 1 | WS | Agarics | HMJAU60615 | ||||||

| Artomyces pyxidatus (Pers.) Jülich | Auriscalpiaceae | Artomyces | √ | √ | 7 | WS | Coral fungi | HMJAU60616 | |||||

| Bjerkandera adusta (Willd.) P. Karst. | Phanerochaetaceae | Bjerkandera | √ | 1 | WS | Polyporoid fungi | HMJAU60617 | ||||||

| Boletus aereus Bull. | Boletaceae | Boletus | √ | 2 | EM | Boletes | HMJAU60618 | ||||||

| Boletus edulis Bull. | Boletaceae | Boletus | √ | √ | 4 | EM | Boletes | HMJAU60619 | |||||

| Bothia castanella (Peck) Halling, T.J. Baroni & Manfr. Binder | Boletaceae | Bothia | √ | 2 | EM | Boletes | HMJAU60620 | ||||||

| Bulgaria inquinans (Pers.) Fr. | Phacidiaceae | Bulgaria | √ | 1 | WS | Larger Ascomytetes | HMJAU60621 | ||||||

| Butyriboletus regius D. Arora & J.L. Frank | Boletaceae | Butyriboletus | √ | 2 | EM | Boletes | HMJAU60622 | OL891490 | |||||

| Butyriboletus roseoflavus (Hai B. Li & Hai L. Wei) D. Arora & J.L. Frank | Boletaceae | Butyriboletus | √ | 3 | EM | Boletes | HMJAU60623 | OL891497 | |||||

| Calocybe persicolor (Fr.) Singer | Lyophyllaceae | Calocybe | √ | 3 | SS | Agarics | HMJAU60624 | ||||||

| Chalciporus piperatus (Bull.) Bataille | Boletaceae | Chalciporus | √ | 1 | EM | Boletes | HMJAU60625 | ||||||

| Chroogomphus helveticus (Singer) M.M. Moser | Gomphidiaceae | Chroogomphus | √ | 4 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60626 | OL891485 | |||||

| Clavaria fragilis Holmsk. | Clavariaceae | Clavaria | √ | 1 | SS | Coral fungi | HMJAU60627 | ||||||

| Clavulinopsis corniculata (Schaeff.) Corner | Clavariaceae | Clavulinopsis | √ | 1 | SS | Coral fungi | HMJAU60628 | ||||||

| Clavulinopsis sulcata Overeem | Clavariaceae | Clavulinopsis | √ | 10 | SS | Coral fungi | HMJAU60629 | ||||||

| Clitocybe fasciculata H.E. Bigelow & A.H. Sm. | Tricholomataceae | Clitocybe | √ | √ | √ | √ | 2 | LS | Agarics | HMJAU60630 | |||

| Clitocybe geotropa (Bull.) Quél. | Tricholomataceae | Clitocybe | √ | 1 | LS | Agarics | HMJAU60631 | ||||||

| Clitocybe gibba (Pers.) P. Kumm. | Tricholomataceae | Clitocybe | √ | 4 | LS | Agarics | HMJAU60632 | ||||||

| Clitocybe odora (Bull.) P. Kumm. | Tricholomataceae | Clitocybe | √ | 1 | LS | Agarics | HMJAU60633 | ||||||

| Clitocybe subditopoda Peck | Tricholomataceae | Clitocybe | √ | √ | √ | 10 | LS | Agarics | HMJAU60634 | ||||

| Coltricia crassa Y.C. Dai | Hymenochaetaceae | Coltricia | √ | 2 | EM | Polyporoid fungi | HMJAU60635 | ||||||

| Coltricia strigosipes Corner | Hymenochaetaceae | Coltricia | √ | 1 | EM | Polyporoid fungi | HMJAU60636 | ||||||

| Coprinellus disseminatus (Pers.) J.E. Lange | Psathyrellaceae | Coprinellus | √ | 8 | SS | Agarics | HMJAU60637 | ||||||

| Coprinellus radians (Desm.) Vilgalys, Hopple & Jacq. Johnson | Psathyrellaceae | Coprinellus | √ | 5 | SS | Agarics | HMJAU60638 | ||||||

| Coprinus comatus (O.F. Müll.) Pers. | Agaricaceae | Coprinus | √ | 1 | DS | Agarics | HMJAU60639 | ||||||

| Cordyceps militaris Cordyceps militaris (L.) Fr. | Cordycipitaceae | Cordyceps | √ | 3 | EI | Larger Ascomytetes | HMJAU60640 | ||||||

| Cortinarius anomalus (Fr.) Fr. | Cortinariaceae | Cortinarius | √ | 2 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60641 | OL891464 | |||||

| Cortinarius armillatus (Fr.) Fr. | Cortinariaceae | Cortinarius | √ | 4 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60642 | OL891465 | |||||

| Cortinarius balaustinus Fr. | Cortinariaceae | Cortinarius | √ | 3 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60643 | ||||||

| Cortinarius bivelus (Fr.) Fr. | Cortinariaceae | Cortinarius | √ | √ | 5 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60644 | OL891467 | ||||

| Cortinarius caperatus (Pers.) Fr. | Cortinariaceae | Cortinarius | √ | 1 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60645 | OL891466 | |||||

| Cortinarius cotoneus Fr. | Cortinariaceae | Cortinarius | √ | √ | 3 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60646 | OL891468 | ||||

| Cortinarius ectypus J. Favre | Cortinariaceae | Cortinarius | √ | 2 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60647 | ||||||

| Cortinarius flammeouraceus Niskanen, Kytov., Liimat., Ammirati & Dima | Cortinariaceae | Cortinarius | √ | 4 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60648 | OL891470 | |||||

| Cortinarius hesleri Ammirati, Niskanen, Liimat. & Matheny | Cortinariaceae | Cortinarius | √ | 1 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60649 | ||||||

| Cortinarius pholideus (Lilj.) Fr. | Cortinariaceae | Cortinarius | √ | 3 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60650 | OL891469 | |||||

| Cortinarius sanguineus (Wulfen) Gray | Cortinariaceae | Cortinarius | √ | 2 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60651 | ||||||

| Cortinarius subbalaustinus Rob. Henry | Cortinariaceae | Cortinarius | √ | 1 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60652 | ||||||

| Cortinarius torvus (Fr.) Fr. | Cortinariaceae | Cortinarius | √ | 1 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60653 | ||||||

| Cotylidia diaphana (Cooke) Lentz | Rickenellaceae | Cotylidia | √ | 4 | SS | Jelly fungi | HMJAU60654 | ||||||

| Craterellus cornucopioides (L.) Pers. | Hydnaceae | Craterellus | √ | 1 | EM | Cantharelloid | HMJAU60655 | ||||||

| Crepidotus applanatus (Pers.) P. Kumm. | Crepidotaceae | Crepidotus | √ | 1 | WS | Agarics | HMJAU60656 | ||||||

| Crepidotus malachius Sacc. | Crepidotaceae | Crepidotus | √ | 5 | WS | Agarics | HMJAU60657 | ||||||

| Cyclocybe erebia (Fr.) Vizzini & Matheny | Tubariaceae | Cyclocybe | √ | 2 | SS | Agarics | HMJAU60658 | ||||||

| Cystoderma granulosum (Batsch) Fayod | Agaricaceae | Cystoderma | √ | 4 | SS | Agarics | HMJAU60659 | ||||||

| Dacrymyces chrysospermus Berk. & M.A. Curtis | Dacrymycetaceae | Dacrymyces | √ | 3 | WS | Jelly fungi | HMJAU60660 | ||||||

| Dacrymyces yunnanensis B. Liu & L. Fan | Dacrymycetaceae | Dacrymyces | √ | √ | 6 | WS | Jelly fungi | HMJAU60661 | |||||

| Daldinia concentrica (Bolton) Ces. & De Not. | Hypoxylaceae | Daldinia | √ | 5 | WS | Larger Ascomytetes | HMJAU60662 | ||||||

| Elmerina cladophora (Berk.) Bres. | Auriculariaceae | Elmerina | √ | √ | 3 | WS | Polyporoid fungi | HMJAU60663 | |||||

| Elmerina hispida (Imazeki) Y.C. Dai & L.W. Zhou | Auriculariaceae | Elmerina | √ | 1 | WS | Polyporoid fungi | HMJAU60664 | ||||||

| Entoloma abortivum (Berk. & M.A. Curtis) Donk | Entolomataceae | Entoloma | √ | 2 | SS | Agarics | HMJAU60665 | ||||||

| Entoloma alboumbonatum Hesler | Entolomataceae | Entoloma | √ | 2 | SS | Agarics | HMJAU60666 | ||||||

| Entoloma caespitosum W.M. Zhang | Entolomataceae | Entoloma | √ | 5 | SS | Agarics | HMJAU60667 | ||||||

| Entoloma clypeatum (L.) P. Kumm. | Entolomataceae | Entoloma | √ | 4 | SS | Agarics | HMJAU60668 | ||||||

| Entoloma holoconiotum (Largent & Thiers) Noordel. & Co-David | Entolomataceae | Entoloma | √ | 4 | SS | Agarics | HMJAU60669 | ||||||

| Entoloma mediterraneense Noordel. & Hauskn. | Entolomataceae | Entoloma | √ | 1 | SS | Agarics | HMJAU60670 | ||||||

| Entoloma rhodopolium (Fr.) P. Kumm. | Entolomataceae | Entoloma | √ | 2 | SS | Agarics | HMJAU60671 | ||||||

| Entonaema liquescens Möller | Hypoxylaceae | Entonaema | √ | 3 | WS | Larger Ascomytetes | HMJAU60672 | ||||||

| Favolus squamosus (Huds.) A. Ames | Polyporaceae | Favolus | √ | 1 | WS | Polyporoid fungi | HMJAU60673 | ||||||

| Flammulaster erinaceellus (Peck) Watling | Tubariaceae | Flammulaster | √ | 6 | WS | Agarics | HMJAU60674 | ||||||

| Galerina helvoliceps (Berk. & M.A. Curtis) Singe | Hymenogastraceae | Galerina | √ | 4 | WS | Agarics | HMJAU60675 | ||||||

| Galerina marginata (Batsch) Kühner | Hymenogastraceae | Galerina | √ | 4 | WS | Agarics | HMJAU60676 | ||||||

| Geastrum triplex Jungh. | Geastraceae | Geastrum | √ | 1 | LS | Gasteroid fungi | HMJAU60677 | ||||||

| Gerhardtia borealis (Fr.) Contu & A. Ortega | Lyophyllaceae | Gerhardtia | √ | 3 | SS | Agarics | HMJAU60678 | ||||||

| Gerronema nemorale Har. Takah. | Marasmiaceae | Gerronema | √ | 1 | WS | Agarics | HMJAU60679 | ||||||

| Gloeostereum incarnatum S. Ito & S. Imai | Cyphellaceae | Gloeostereum | √ | 4 | WS | Polyporoid fungi | HMJAU60680 | ||||||

| Gomphidius maculatus (Scop.) Fr. | Gomphidiaceae | Gomphidius | √ | 2 | EM | Cantharelloid | HMJAU60681 | ||||||

| Gymnopilus junonius (Fr.) P.D. Orton | Hymenogastraceae | Gymnopilus | √ | 3 | WS | Agarics | HMJAU60682 | ||||||

| Gymnopilus penetrans (Fr.) Murrill | Hymenogastraceae | Gymnopilus | √ | 2 | WS | Agarics | HMJAU60683 | ||||||

| Gymnopilus suberis (Maire) Singer | Hymenogastraceae | Gymnopilus | √ | 6 | WS | Agarics | HMJAU60684 | ||||||

| Gymnopus alnicola J.L. Mata & Halling | Omphalotaceae | Gymnopus | √ | 4 | LS | Agarics | HMJAU60685 | ||||||

| Gymnopus confluens (Pers.) Antonín, Halling & Noordel. | Omphalotaceae | Gymnopus | √ | √ | 14 | LS | Agarics | HMJAU60686 | OL884222 | ||||

| Gymnopus densilamellatus Antonín, Ryoo & Ka | Omphalotaceae | Gymnopus | √ | √ | √ | √ | 25 | LS | Agarics | HMJAU60687 | OL884223 | ||

| Gymnopus dryophilus (Bull.) Murrill | Omphalotaceae | Gymnopus | √ | √ | 30 | LS | Agarics | HMJAU60688 | OL891463 | ||||

| Gymnopus gibbosus (Corner) A.W. Wilson, Desjardin & E. Horak | Omphalotaceae | Gymnopus | √ | 7 | LS | Agarics | HMJAU60689 | OL884224 | |||||

| Gymnopus loiseleurietorum (M.M. Moser, Gerhold & Tobies) Antonín & Noordel. | Omphalotaceae | Gymnopus | √ | 7 | LS | Agarics | HMJAU60690 | ||||||

| Harrya chromapes (Frost) Halling, Nuhn, Osmundson & Manfr. | Boletaceae | Harrya | √ | 1 | EM | Boletes | HMJAU60691 | OL891492 | |||||

| Hebeloma birrus (Fr.) Gillet | Hymenogastraceae | Hebeloma | √ | 6 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60692 | OL891483 | |||||

| Heliocybe sulcata (Berk.) Redhead & Ginns | Gloeophyllaceae | Heliocybe | √ | 2 | WS | Agarics | HMJAU60693 | ||||||

| Helvella crispa (Scop.) Fr. | Hydnaceae | Helvella | √ | √ | 2 | EM | Larger Ascomytetes | HMJAU60694 | |||||

| Helvella elastica Bull. | Helvellaceae | Helvella | √ | 1 | EM | Larger Ascomytetes | HMJAU60695 | ||||||

| Helvella macropus (Pers.) P. Karst. | Helvellaceae | Helvella | √ | √ | 3 | EM | Larger Ascomytetes | HMJAU60696 | |||||

| Hemistropharia albocrenulata (Peck) Jacobsson & E. Larss. | Tubariaceae | Hemistropharia | √ | 1 | SS | Agarics | HMJAU60697 | ||||||

| Hericium erinaceus (Bull.) Pers. | Hericiaceae | Hericium | √ | 1 | WS | Hydnaceous fungi | HMJAU60698 | ||||||

| Humaria hemisphaerica (F.H. Wigg.) Fuckel | Pyronemataceae | Humaria | √ | 1 | EM | Larger Ascomytetes | HMJAU60699 | ||||||

| Hydnellum aurantiacum (Batsch) P. Karst. | Bankeraceae | Hydnellum | √ | 2 | EM | Hydnaceous fungi | HMJAU60700 | OL891471 | |||||

| Hydnellum peckii Banker | Bankeraceae | Hydnellum | √ | 2 | EM | Hydnaceous fungi | HMJAU60701 | OL891487 | |||||

| Hygrocybe cantharellus (Schwein.) Murrill | Hygrophoraceae | Hygrocybe | √ | 5 | SS | Agarics | HMJAU60702 | ||||||

| Hygrocybe chlorophana (Fr.) Wünsche | Hygrophoraceae | Hygrocybe | √ | 5 | SS | Agarics | HMJAU60703 | ||||||

| Hygrocybe coccinea (Schaeff.) P. Kumm. | Hygrophoraceae | Hygrocybe | √ | 4 | SS | Agarics | HMJAU60704 | ||||||

| Hygrocybe coccineocrenata.D. Orton) M.M. Moser | Hygrophoraceae | Hygrocybe | √ | 5 | SS | Agarics | HMJAU60705 | ||||||

| Hygrocybe miniata (Fr.) P. Kumm. | Hygrophoraceae | Hygrocybe | √ | 4 | SS | Agarics | HMJAU60706 | ||||||

| Hygrocybe reidii Kühner | Hygrophoraceae | Hygrocybe | √ | 1 | SS | Agarics | HMJAU60707 | ||||||

| Hygrophoropsis aurantiaca (Wulfen) Maire | Hygrophoropsidaceae | Hygrophoropsis | √ | √ | 7 | LS | Agarics | HMJAU60708 | OL891484 | ||||

| Hygrophorus conicus (Schaeff.) Fr. | Hygrophoraceae | Hygrophorus | √ | √ | 6 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60709 | |||||

| Hygrophorus nemoreus (Pers.) Fr. | Hygrophoraceae | Hygrophorus | √ | √ | 9 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60710 | |||||

| Hygrophorus pudorinus (Fr.) Fr. | Hygrophoraceae | Hygrophorus | √ | 1 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60711 | ||||||

| Hygrophorus russula (Schaeff. ex Fr.) Kauffman | Hygrophoraceae | Hygrophorus | √ | 2 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60712 | ||||||

| Hypholoma capnoides (Fr.) P. Kumm. | Strophariaceae | Hypholoma | √ | 2 | WS | Agarics | HMJAU60713 | ||||||

| Hypholoma sublateritium (Fr.) Quél. | Strophariaceae | Hypholoma | √ | 4 | WS | Agarics | HMJAU60714 | ||||||

| Infundibulicybe geotropa (Bull.) Harmaja | Tricholomataceae | Infundibulicybe | √ | 2 | SS | Agarics | HMJAU60715 | ||||||

| Infundibulicybe gibba (Pers.) Harmaja | Tricholomataceae | Infundibulicybe | √ | 2 | SS | Agarics | HMJAU60716 | ||||||

| Inocybe assimilata Britzelm. | Inocybaceae | Inocybe | √ | 2 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60717 | ||||||

| Inocybe asterospora Quél. | Inocybaceae | Inocybe | √ | 1 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60718 | ||||||

| Inocybe suaveolens D.E. Stuntz | Inocybaceae | Inocybe | √ | 2 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60719 | OL891472 | |||||

| Inonotus hispidus (Bull.) P. Karst. | Hymenochaetaceae | Inonotus | √ | 3 | WS | Polyporoid fungi | HMJAU60720 | ||||||

| Laccaria amethystina Cooke | Hydnangiaceae | Laccaria | √ | 4 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60721 | ||||||

| Laccaria laccata (Scop.) Cooke | Hydnangiaceae | Laccaria | √ | 4 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60722 | ||||||

| Lactarius albidocinereus X.H. Wang, S.F. Shi & T. Bau | Russulaceae | Lactarius | √ | 2 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60723 | OL891473 | |||||

| Lactarius brunneoviolascens Bon | Russulaceae | Lactarius | √ | 1 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60724 | ||||||

| Lactarius conglutinatus X.H. Wang | Russulaceae | Lactarius | √ | 6 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60725 | ||||||

| Lactarius deterrimus Gröger | Russulaceae | Lactarius | √ | 5 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60726 | ||||||

| Lactarius flavidus Boud. | Russulaceae | Lactarius | √ | 1 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60727 | ||||||

| Lactarius glyciosmus (Fr.) Fr. | Russulaceae | Lactarius | √ | 1 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60728 | ||||||

| Lactarius hirtipes J.Z. Ying | Russulaceae | Lactarius | √ | 3 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60729 | ||||||

| Lactarius lilacinus Fr. | Russulaceae | Lactarius | √ | 3 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60730 | ||||||

| Lactarius pallidus Pers. | Russulaceae | Lactarius | √ | 2 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60731 | ||||||

| Lactarius piperatus (L.) Pers. | Russulaceae | Lactarius | √ | 1 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60732 | ||||||

| Lactarius proximellus Beardslee & Burl. | Russulaceae | Lactarius | √ | 1 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60733 | ||||||

| Lactarius pubescens Fr. | Russulaceae | Lactarius | √ | 1 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60734 | ||||||

| Lactarius subvellereus Peck | Russulaceae | Lactarius | √ | 2 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60735 | ||||||

| Lactarius torminosus (Schaeff.) Pers. | Russulaceae | Lactarius | √ | 2 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60736 | ||||||

| Lactarius trivialis (Fr.) Fr. | Russulaceae | Lactarius | √ | 1 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60737 | OL891474 | |||||

| Lactarius vietus (Fr.) Fr. | Russulaceae | Lactarius | √ | 2 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60738 | ||||||

| Lactarius volemus (Fr.) Fr. | Russulaceae | Lactarius | √ | 3 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60739 | ||||||

| Lactarius zonarius (Bull.) Fr. | Russulaceae | Lactarius | √ | √ | 2 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60740 | |||||

| Lactifluus bertillonii (Neuhoff ex Z. Schaef.) Verbeken | Russulaceae | Lactifluus | √ | 1 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60741 | OL891489 | |||||

| Lactifluus pilosus (Verbeken, H.T. Le & Lumyong) Verbeken | Russulaceae | Lactifluus | √ | 1 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60742 | ||||||

| Laetiporus sulphureus (Bull.) Murrill | Laetiporaceae | Laetiporus | √ | √ | 2 | WS | Polyporoid fungi | HMJAU60743 | |||||

| Leccinum aurantiacum (Bull.) Gray | Boletaceae | Leccinum | √ | 2 | EM | Boletes | HMJAU60744 | ||||||

| Leccinum scabrum (Bull.) Gray | Boletaceae | Leccinum | √ | 1 | EM | Boletes | HMJAU60745 | ||||||

| Leccinum versipelle (Fr. & Hök) Snell | Boletaceae | Leccinum | √ | 1 | EM | Boletes | HMJAU60746 | ||||||

| Lentinellus ursinus (Fr.) Kühner | Auriscalpiaceae | Lentinellus | √ | 6 | WS | Agarics | HMJAU60747 | ||||||

| Lentinus edodes (Berk.) Singer | Omphalotaceae | Lentinus | √ | 2 | WS | Agarics | HMJAU60748 | ||||||

| Lentinus sajor-caju (Fr.) Fr. | Polyporaceae | Lentinus | √ | 6 | WS | Agarics | HMJAU60749 | OL891475 | |||||

| Leotia lubrica (Scop.) Pers. | Leotiaceae | Leotia | √ | 4 | SS | Larger Ascomytetes | HMJAU60750 | ||||||

| Lepiota castanea Quél. | Agaricaceae | Lepiota | √ | 5 | LS | Agarics | HMJAU60751 | ||||||

| Lepiota cristata (Bolton) P. Kumm. | Agaricaceae | Lepiota | √ | 4 | LS | Agarics | HMJAU60752 | ||||||

| Lepista nuda (Bull.) Cooke | Tricholomataceae | Lepista | √ | √ | 9 | SS | Agarics | HMJAU60753 | |||||

| Lepista personata (Fr.) Cooke | Tricholomataceae | Lepista | √ | 1 | SS | Agarics | HMJAU60754 | ||||||

| Leucocybe connata (Schumach.) Vizzini, P. Alvarado, G. Moreno & Consiglio | Lyophyllaceae | Leucocybe | √ | 3 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60755 | ||||||

| Lycoperdon mammiforme Pers. | Lycoperdaceae | Lycoperdon | √ | 8 | SS | Agarics | HMJAU60756 | ||||||

| Lycoperdon perlatum Pers. | Lycoperdaceae | Lycoperdon | √ | √ | 5 | SS | Gasteroid fungi | HMJAU60757 | |||||

| Lycoperdon umbrinum Pers. | Lycoperdaceae | Lycoperdon | √ | 3 | SS | Gasteroid fungi | HMJAU60758 | ||||||

| Lyophyllum decastes (Fr.) Singer | Lyophyllaceae | Lyophyllum | √ | 3 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60759 | ||||||

| Lyophyllum infumatum (Bres.) Kühner | Lyophyllaceae | Lyophyllum | √ | 1 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60760 | OL891476 | |||||

| Macrocystidia cucumis (Pers.) Joss. | Macrocystidiaceae | Macrocystidia | √ | 2 | SS | Agarics | HMJAU60761 | ||||||

| Marasmius confertus Berk. & Broome | Marasmiaceae | Marasmius | √ | 2 | LS | Agarics | HMJAU60762 | ||||||

| Marasmius maximus Hongo | Marasmiaceae | Marasmius | √ | √ | 8 | LS | Agarics | HMJAU60763 | |||||

| Marasmius nigrodiscus (Peck) Halling | Marasmiaceae | Marasmius | √ | 2 | LS | Agarics | HMJAU60764 | ||||||

| Marasmius occultatiformis Antonín, Ryoo & H.D. Shin | Marasmiaceae | Marasmius | √ | 4 | LS | Agarics | HMJAU60765 | ||||||

| Marasmius siccus (Schwein.) Fr. | Marasmiaceae | Marasmius | √ | 1 | LS | Agarics | HMJAU60766 | ||||||

| Megacollybia clitocyboidea R.H. Petersen, Takehashi & Nagas. | Megacollybia | Megacollybia | √ | √ | 4 | WS | Agarics | HMJAU60767 | |||||

| Melanoleuca cognata (Huds.) Fr. | Tricholomataceae | Melanoleuca | √ | 1 | SS | Agarics | HMJAU60768 | ||||||

| Mucidula brunneomarginata Lj.N. Vassiljeva) R.H. Petersen | Physalacriaceae | Mucidula | √ | 2 | WS | Agarics | HMJAU60769 | ||||||

| Mutinus caninus (Huds.) Fr. | Phallaceae | Mutinus | √ | 4 | LS | Gasteroid fungi | HMJAU60770 | ||||||

| Mycena galericulata (Scop.) Gray | Mycenaceae | Mycena | √ | 5 | LS | Agarics | HMJAU60771 | ||||||

| Mycena haematopus (Pers.) P. Kumm. | Mycenaceae | Mycena | √ | 3 | LS | Agarics | HMJAU60772 | ||||||

| Mycena pelianthina (Fr.) Quél. | Mycenaceae | Mycena | √ | 1 | LS | Agarics | HMJAU60773 | ||||||

| Mycena polygramma (Bull.) Gray | Mycenaceae | Mycena | √ | 2 | LS | Agarics | HMJAU60774 | ||||||

| Mycena pura (Pers.) P. Kumm. | Mycenaceae | Mycena | √ | √ | √ | 4 | LS | Agarics | HMJAU60775 | ||||

| Mycena roseocandida (Peck) Sacc. | Mycenaceae | Mycena | √ | 1 | LS | Agarics | HMJAU60776 | ||||||

| Mycena sanguinolenta (Alb. & Schwein.) P. Kumm. | Mycenaceae | Mycena | √ | 8 | LS | Agarics | HMJAU60777 | ||||||

| Mycena stylobates (Pers.) P. Kumm. | Mycenaceae | Mycena | √ | √ | 12 | LS | Agarics | HMJAU60778 | |||||

| Neolentinus cyathiformis (Schaeff.) Della Magg. & Trassin. | Gloeophyllaceae | Neolentinus | √ | √ | 15 | WS | Agarics | HMJAU60779 | OL891477 | ||||

| Omphalina pyxidata (Bull.) Quél. | Tricholomataceae | Omphalina | √ | 3 | LS | Agarics | HMJAU60780 | ||||||

| Ophiocordyceps nutans (Pat.) G.H. Sung, J.M. Sung, Hywel-Jones & Spatafora | Ophiocordycipitaceae | Ophiocordyceps | √ | 1 | EI | Larger Ascomytetes | HMJAU60781 | ||||||

| Oudemansiella mucida (Schrad.) Höhn. | Physalacriaceae | Oudemansiella | √ | 4 | WS | Agarics | HMJAU60782 | ||||||

| Paxillus involutus (Batsch) Fr. | Paxillaceae | Paxillus | √ | √ | 2 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60783 | |||||

| Paxillus orientalis Gelardi, Vizzini, E. Horak & G. Wu | Paxillaceae | Paxillus | √ | 1 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60784 | ||||||

| Peziza domiciliana Cooke | Pezizaceae | Peziza | √ | 3 | SS | Larger Ascomytetes | HMJAU60785 | ||||||

| Phallus tenuissimus T.H. Li, W.Q. Deng & B. Liu | Phallaceae | Phallus | √ | 2 | LS | Gasteroid fungi | HMJAU60786 | ||||||

| Phellinus pomaceus (Pers.) Maire | Hymenochaetaceae | Phellinus | √ | √ | 2 | WS | Polyporoid fungi | HMJAU60787 | |||||

| Pholiota aurivella (Batsch) P. Kumm. | Strophariaceae | Pholiota | √ | 4 | WS | Agarics | HMJAU60788 | ||||||

| Pholiota squarrosoides (Peck) Sacc. | Strophariaceae | Pholiota | √ | 3 | WS | Agarics | HMJAU60789 | ||||||

| Phylloporus yunnanensis N.K. Zeng, Zhu L. Yang & L.P. Tang | Boletaceae | Phylloporus | √ | 2 | EM | Boletes | HMJAU60790 | ||||||

| Phyllotopsis nidulans (Pers.) Singer | Phyllotopsidaceae | Phyllotopsis | √ | 7 | WS | Agarics | HMJAU60791 | ||||||

| Piptoporus soloniensis (Dubois) Pilát | Fomitopsidaceae | Piptoporus | √ | 2 | WS | Polyporoid fungi | HMJAU60792 | OL891488 | |||||

| Pleurotus citrinopileatus Singer | Pleurotaceae | Pleurotus | √ | 4 | WS | Agarics | HMJAU60793 | ||||||

| Pleurotus ostreatus (Jacq.) P. Kumm. | Pleurotaceae | Pleurotus | √ | √ | 8 | WS | Agarics | HMJAU60794 | OL891478 | ||||

| Pleurotus pulmonarius (Fr.) Quél. | Pleurotaceae | Pleurotus | √ | 2 | WS | Agarics | HMJAU60795 | ||||||

| Pluteus atromarginatus (Konrad) Kühner | Pluteaceae | Pluteus | √ | 2 | LS | Agarics | HMJAU60796 | ||||||

| Pluteus cervinus (Schaeff.) P. Kumm. | Pluteaceae | Pluteus | √ | 1 | LS | Agarics | HMJAU60797 | ||||||

| Pluteus hispidulus (Fr.) Gillet | Pluteaceae | Pluteus | √ | 1 | LS | Agarics | HMJAU60798 | ||||||

| Pluteus leoninus (Schaeff.) P. Kumm | Pluteaceae | Pluteus | √ | √ | 1 | LS | Agarics | HMJAU60799 | |||||

| Pluteus phlebophorus (Ditmar) P. Kumm. | Pluteaceae | Pluteus | √ | 2 | LS | Agarics | HMJAU60800 | ||||||

| Pluteus pouzarianus Singer | Pluteaceae | Pluteus | √ | 2 | LS | Agarics | HMJAU60801 | ||||||

| Podoscypha nitidula (Berk.) Pat. | Podoscyphaceae | Podoscypha | √ | 3 | WS | Polyporoid fungi | HMJAU60802 | ||||||

| Polyporus arcularius (Batsch) Fr. | Polyporaceae | Polyporus | √ | 10 | WS | Polyporoid fungi | HMJAU60803 | ||||||

| Polyporus submelanopus H.J. Xue & L.W. Zhou | Polyporaceae | Polyporus | √ | 1 | WS | Polyporoid fungi | HMJAU60804 | ||||||

| Polyporus umbellatus (Pers.) Fr. | Polyporaceae | Polyporus | √ | 4 | SS | Polyporoid fungi | HMJAU60805 | ||||||

| Psathyrella delineata (Peck) A.H. Sm. | Psathyrellaceae | Psathyrella | √ | 1 | WS | Agarics | HMJAU60806 | ||||||

| Psathyrella typhae (Kalchbr.) A. Pearson & Dennis | Psathyrellaceae | Psathyrella | √ | 4 | WS | Agarics | HMJAU60807 | ||||||

| Pseudolaccaria fellea (Peck) Vizzini, Matheny & Consiglio & M. Marchetti | Callistosporiaceae | Pseudolaccaria | √ | 3 | WS | Agarics | HMJAU60808 | ||||||

| Pseudoplectania nigrella (Pers.) Fuckel | Sarcosomataceae | Pseudoplectania | √ | 5 | SS | Larger Ascomytetes | HMJAU60809 | ||||||

| Pulveroboletus macrosporus G. Wu & Zhu L. Yang | Boletaceae | Pulveroboletus | √ | 1 | EM | Boletes | HMJAU60810 | ||||||

| Ramaria cokeri R.H. Petersen | Gomphaceae | Ramaria | √ | √ | 2 | EM | Coral fungi | HMJAU60811 | |||||

| Ramaria fennica (P. Karst.) Ricken | Gomphaceae | Ramaria | √ | 1 | EM | Coral fungi | HMJAU60812 | ||||||

| Ramaria marrii Scates | Gomphaceae | Ramaria | √ | 2 | EM | Coral fungi | HMJAU60813 | ||||||

| Ramaria sanguinipes R.H. Petersen & M. Zang | Gomphaceae | Ramaria | √ | 2 | EM | Coral fungi | HMJAU60814 | ||||||

| Ramaria stricta (Pers.) Quél. | Gomphaceae | Ramaria | √ | 3 | EM | Coral fungi | HMJAU60815 | ||||||

| Rhodocollybia butyracea (Bull.) Lennox | Omphalotaceae | Rhodocollybia | √ | √ | 12 | SS | Agarics | HMJAU60816 | |||||

| Russula aeruginea Lindblad ex Fr. | Russulaceae | Russula | √ | 3 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60817 | ||||||

| Russula amoena Quél. | Russulaceae | Russula | √ | √ | 2 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60818 | |||||

| Russula cyanoxantha (Schaeff.) Fr. | Russulaceae | Russula | √ | 1 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60819 | ||||||

| Russula emetica (Schaeff.) Pers. | Russulaceae | Russula | √ | √ | √ | 18 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60820 | ||||

| Russula foetens Pers. | Russulaceae | Russula | √ | √ | 3 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60821 | |||||

| Russula furcata Pers. | Russulaceae | Russula | √ | 3 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60822 | ||||||

| Russula grata Britzelm. | Russulaceae | Russula | √ | 2 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60823 | ||||||

| Russula lakhanpalii A. Ghosh, K. Das & R.P. Bhatt | Russulaceae | Russula | √ | 2 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60824 | OL891479 | |||||

| Russula paludosa Britzelm. | Russulaceae | Russula | √ | √ | 6 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60825 | |||||

| Russula risigallina (Batsch) Sacc. | Russulaceae | Russula | √ | 3 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60826 | ||||||

| Russula rosea Pers. | Russulaceae | Russula | √ | √ | 4 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60827 | |||||

| Russula senecis S. Imai | Russulaceae | Russula | √ | 6 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60828 | ||||||

| Russula sororia (Fr.) Romell | Russulaceae | Russula | √ | 3 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60829 | ||||||

| Russula veternosa Fr. | Russulaceae | Russula | √ | 2 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60830 | ||||||

| Russula vinosa Lindblad | Russulaceae | Russula | √ | 2 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60831 | ||||||

| Russula virescens (Schaeff.) Fr. | Russulaceae | Russula | √ | 1 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60832 | ||||||

| Sarcodontia spumea (Sowerby) Spirin | Meruliaceae | Sarcodontia | √ | 3 | WS | Polyporoid fungi | HMJAU60833 | ||||||

| Schizophyllum commune Fr. | Schizophyllaceae | Schizophyllum | √ | 4 | WS | Agarics | HMJAU60834 | ||||||

| Scleroderma areolatum Ehrenb. | Sclerodermataceae | Scleroderma | √ | 4 | EM | Gasteroid fungi | HMJAU60835 | ||||||

| Sowerbyella rhenana (Fuckel) J. Moravec | Pyronemataceae | Sowerbyella | √ | 5 | EM | Larger Ascomytetes | HMJAU60836 | ||||||

| Spathularia flavida Pers. | Cudoniaceae | Spathularia | √ | 4 | SS | Larger Ascomytetes | HMJAU60837 | ||||||

| Stropharia rugosoannulata Farl. ex Murrill | Tubariaceae | Stropharia | √ | 3 | SS | Agarics | HMJAU60838 | ||||||

| Suillus americanus (Peck) Snell | Suillaceae | Suillus | √ | 1 | EM | Boletes | HMJAU60839 | ||||||

| Suillus granulatus (L.) Roussel | Suillaceae | Suillus | √ | 1 | EM | Boletes | HMJAU60840 | ||||||

| Suillus grevillei (Klotzsch) Singer | Suillaceae | Suillus | √ | √ | 10 | EM | Boletes | HMJAU60841 | OL891494 | ||||

| Suillus luteus (L.) Roussel | Suillaceae | Suillus | √ | √ | 4 | EM | Boletes | HMJAU60842 | OL891496 | ||||

| Suillus placidus (Bonord.) Singer | Suillaceae | Suillus | √ | 3 | EM | Boletes | HMJAU60843 | OL884444 | |||||

| Suillus subaureus (Peck) Snell | Suillaceae | Suillus | √ | 5 | EM | Boletes | HMJAU60844 | OL891495 | |||||

| Suillus tomentosus Singer, Snell & E.A. Dick | Suillaceae | Suillus | √ | 3 | EM | Boletes | HMJAU60845 | ||||||

| Sutorius brunneissimus (W.F. Chiu) G. Wu & Zhu L. Yang | Boletaceae | Sutorius | √ | 1 | EM | Boletes | HMJAU60846 | ||||||

| Tengioboletus glutinosus G. Wu & Zhu L. Yang | Boletaceae | Tengioboletus | √ | √ | 5 | EM | Boletes | HMJAU60847 | |||||

| Tremella Fuciformis Berk. | Tremellaceae | Tremella | √ | 3 | WS | Jelly fungi | HMJAU60848 | ||||||

| Trichoderma rhododendri (Jaklitsch) Jaklitsch & Voglmayr | Hypocreaceae | Trichoderma | √ | 3 | WS | Larger Ascomytetes | HMJAU60849 | ||||||

| Tricholoma matsutake (S. Ito & S. Imai) Singer | Tricholomataceae | Tricholoma | √ | 4 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60850 | ||||||

| Tricholoma psammopus (Kalchbr.) Quél. | Tricholomataceae | Tricholoma | √ | √ | 5 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60851 | OL891480 | ||||

| Tricholoma saponaceum (Fr.) P. Kumm. | Tricholomataceae | Tricholoma | √ | 2 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60852 | ||||||

| Tricholoma sejunctum (Sowerby) Quél. | Sarcoscyphaceae | Tricholoma | √ | 4 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60853 | OL891481 | |||||

| Tricholoma stans (Fr.) Sacc. | Tricholomataceae | Tricholoma | √ | 2 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60854 | ||||||

| Tricholoma subacutum Peck | Tricholomataceae | Tricholoma | √ | √ | 2 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60855 | |||||

| Tricholoma ustale (Fr.) P. Kumm. | Tricholomataceae | Tricholoma | √ | 1 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60856 | OL891482 | |||||

| Tricholoma ustaloides Romagn. | Tricholomataceae | Tricholoma | √ | 1 | EM | Agarics | HMJAU60857 | ||||||

| Tricholomopsis rutilans (Schaeff.) Singer | Tricholomataceae | Tricholomopsis | √ | 2 | SS | Agarics | HMJAU60858 | ||||||

| Tylopilus eximius (Peck) Singer | Boletaceae | Tylopilus | √ | 1 | EM | Boletes | HMJAU60859 | OL891491 | |||||

| Tylopilus felleus (Bull.) P. Karst. | Boletaceae | Tylopilus | √ | 1 | EM | Boletes | HMJAU60860 | ||||||

| Tylopilus virens (W.F. Chiu) Hongo | Boletaceae | Tylopilus | √ | 2 | EM | Boletes | HMJAU60861 | OL891493 | |||||

| Tyromyces lacteus (Fr.) Murrill | Incrustoporiaceae | Tyromyces | √ | 1 | WS | Polyporoid fungi | HMJAU60862 | ||||||

| Vanrija pseudolonga (M. Takash., Sugita, Shinoda & Nakase) Weiß | Cryptococcaceae | Vanrija | √ | 1 | EM | Boletes | HMJAU60863 | ||||||

| Volvopluteus michiganensis (A.H. Sm.) Justo & Minnis | Pluteaceae | Volvopluteus | √ | 1 | SS | Boletes | HMJAU60864 | ||||||

| Wynnea gigantea Berk. & M.A. Curtis | Wynneaceae | Wynnea | √ | √ | 5 | SS | Larger Ascomytetes | HMJAU60865 | |||||

| Xerocomus ferrugineus (Schaeff.) Alessio | Boletaceae | Xerocomus | √ | 1 | EM | Boletes | HMJAU60866 | ||||||

| Xerocomus magniporus M. Zang & R.H. Petersen | Boletaceae | Xerocomus | √ | 1 | EM | Boletes | HMJAU60867 | ||||||

| Xeromphalina campanella (Batsch) Kühner & Maire | Mycenaceae | Xeromphalina | √ | 1 | WS | Agarics | HMJAU60868 | ||||||

| Xylaria hypoxylon (L.) Grev. | Xylariaceae | Xylaria | √ | 4 | WS | Larger Ascomytetes | HMJAU60869 | ||||||

| Xylaria polymorpha (Pers.) Grev. | Xylariaceae | Xylaria | √ | 1 | WS | Larger Ascomytetes | HMJAU60870 | ||||||

| Note: Abbreviations: A = Q. mongolica forest; B = Broad-leaved forest; C = P. koraiensis and Q. mongolica mixed forest, with P. koraiensis as the dominant species; D = P. koraiensis and Q. mongolica mixed forest, with Q. mongolica as the dominant species; E = P. koraiensis forest; F = random collection; N = Number of fruiting bodies; ML = Mode of Life; SN = Specimen Number; EM = ectomycorrhizal; SS = soil saprotroph; WS = wood saprotroph; LS = litter saprotroph; DS = dung saprotroph; EI = endophyte-insect pathogen. | |||||||||||||

Appendix C. Species Scientific Names and Corresponding Abbreviations

| Species | Acronyms | Species | Acronyms | Species | Acronyms | Species | Acronyms | Species | Acronyms |

| Amanita altipes | Ama1 | Cortinarius armillatus | Cor2 (A) | Inocybe assimilata | Ino1 (A) | Leccinum scabrum | Lec2 (D) | Russula vinosa | Ru14 |

| Amanita chepangiana | Ama2 | Cortinarius balaustinus | Cor3 (A) | Inocybe asterospora | Ino2 (A) | Leccinum versipelle | Lec3 (A) | Russula virescens | Ru15 (A) |

| Amanita excelsa | Ama3 (D) | Cortinarius bivelus | Cor4 | Inocybe suaveolens | Ino3 | Leucocybe connata | Leu1 (A) | Scleroderma areolatum | Scl1 |

| Amanita flavipes | Ama4 | Cortinarius caperatus | Cor5 (A) | Laccaria amethystina | Lac1 (D) | Lyophyllum decastes | Lyo1 (A) | Sowerbyella rhenana | Sow1 (D) |

| Amanita fuliginea | Ama5 | Cortinarius cotoneus | Cor6 | Laccaria laccata | Lac2 | Lyophyllum infumatum | Lyo2 | Suillus americanus | Sui1 |

| Amanita hemibapha | Ama6 | Cortinarius ectypus | Cor7 (A) | Lactarius albidocinereus | Lact1 (D) | Paxillus involutus | Pax1 | Suillus grevillei | Sui2 |

| Amanita ibotengutake | Ama7 | Cortinarius flammeouraceus | Cor8 (A) | Lactarius brunneoviolascens | Lact2 (A) | Paxillus orientalis | Pax2 (A) | Suillus luteus | Sui3 |

| Amanita oberwinklerana | Ama8 | Cortinarius hesleri | Cor9 (A) | Lactarius conglutinatus | Lact3 (A) | Phylloporus yunnanensis | Phy1 (A) | Suillus placidus | Sui4 |

| Amanita orsonii | Ama9 | Cortinarius pholideus | Cor10 (D) | Lactarius deterrimus | Lact4 | Pulveroboletus macrosporus | Pul1 (D) | Suillus subaureus | Sui5 (A) |

| Amanita pallidocarnea | Ama10 | Cortinarius sanguineus | Cor11 (D) | Lactarius flavidus | Lact5 (A) | Ramaria cokeri | Ram 1 | Suillus tomentosus | Sui6 (A) |

| Amanita pallidorosea | Ama11 (A) | Cortinarius subbalaustinus | Cor12 (A) | Lactarius glyciosmus | Lact6 (A) | Ramaria marrii | Ram2 (A) | Sutorius brunneissimus | Sut1 |

| Amanita rimosa | Ama12 (A) | Cortinarius torvus | Cor13 (A) | Lactarius hirtipes | Lact7 (A) | Ramaria sanguinipes | Ram 3 | Tengioboletus glutinosus | Ten1 |

| Amanita rubescens | Ama13 | Craterellus cornucopioides | Cra1(A) | Lactarius lilacinus | Lact8 (A) | Ramaria stricta | Ram 4 | Tricholoma matsutake | Tri1 |

| Amanita subglobosa | Ama14 (A) | Gomphidius maculatus | Gom1 | Lactarius pallidus | Lact9 | Russula aeruginea | Rus1 (D) | Tricholoma psammopus | Tri2 |

| Amanita vaginata | Ama15 | Harrya chromapes | Har1 (A) | Lactarius piperatus | Lact10 (A) | Russula amoena | Rus2 | Tricholoma saponaceum | Tri3 |

| Amanita virosa | Ama16 | Hebeloma birrus | Heb1 (A) | Lactarius proximellus | Lact11 | Russula cyanoxantha | Rus3 | Tricholoma sejunctum | Tri4 |

| Boletus aereus | Bol1 | Helvella crispa | Hel1 | Lactarius pubescens | Lact12 (A) | Russula emetica | Rus4 | Tricholoma stans | Tri5 (D) |

| Boletus edulis | Bol2 | Helvella elastica | Hel2 | Lactarius subvellereus | Lact13 (A) | Russula foetens | Rus5 | Tricholoma subacutum | Tri6 |

| Bothia castanella | Bot1 (A) | Helvella macropus | Hel3 | Lactarius torminosus | Lact14 (D) | Russula furcata | Rus6 (D) | Tricholoma ustale | Tri7 (D) |

| Butyriboletus regius | But1 (A) | Humaria hemisphaerica | Hum1 | Lactarius trivialis | Lact15 (A) | Russula grata | Rus7(A) | Tricholoma ustaloides | Tri8 (A) |

| Butyriboletus roseoflavu | But2 | Hydnellum aurantiacum | Hyd1 | Lactarius vietus | Lact16 (A) | Russula lakhanpalii | Rus8 (D) | Tylopilus eximius | Tyl1 (D) |

| Chalciporus piperatus | Cha1 | Hydnellum peckii | Hyd2 | Lactarius volemus | Lact17 (A) | Russula paludosa | Rus9 | Tylopilus felleus | Tyl2 |

| Chroogomphus helveticus | Chr1 | Hygrophorus conicus | Hyg1 | Lactarius zonarius | Lact18 | Russula rosea | Rus10 | Tylopilus virens | Tyl3 (A) |

| Coltricia crassa | Col1 | Hygrophorus nemoreus | Hyg2 | Lactifluus bertillonii | Lacti1 (A) | Russula senecis | Rus11 (D) | Vanrija pseudolonga | Van1 |

| Coltricia strigosipes | Col2 (A) | Hygrophorus pudorinus | Hyg3 (A) | Lactifluus pilosus | Lacti2 (A) | Russula sororia | Rus12 (D) | Xerocomus ferrugineus | Xer1 |

| Cortinarius anomalus | Cor1 (D) | Hygrophorus russula | Hyg4 (A) | Leccinum aurantiacum | Lec1 (A) | Russula veternosa | Rus13 (A) | Xerocomus magniporus | Xer2 (A) |

| Note: Abbreviations: Overlapping species labels are marked and noted in parentheses. A = Q. mongolica forest; D = P. koraiensis and Q. mongolica mixed forest, with Q. mongolica as the dominant species. | |||||||||

References

- Clemmensen, K.E.; Bahr, A.; Ovaskainen, O.; Dahlberg, A.; Ekblad, A.; Wallander, H.; Stenlid, J.; Finlay, R.D.; Wardle, D.A.; Lindahl, B.D. Roots and associated fungi drive long-term carbon sequestration in boreal forest. Science 2013, 339, 1615–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talbot, J.M.; Bruns, T.D.; Smith, D.P.; Branco, S.; Glassman, S.I.; Erlandson, S.; Vilgalys, R.; Peay, K.G. Independent roles of ectomycorrhizal and saprotrophic communities in soil organic matter decomposition. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2013, 57, 282–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, X.; Kou, Y. Ectomycorrhizal fungi: Participation in nutrient turnover and community assembly pattern in forest ecosystems. Forests 2020, 11, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petre, C.V.; Balaes, T.; Tănase, C. Lignicolous basidiomycetes as valuable biotechnological agents. Mem. Sci. Sect. Rom. Acad. 2014, 37, 37–62. [Google Scholar]

- Cairney, J.W. Extramatrical mycelia of ectomycorrhizal fungi as moderators of carbon dynamics in forest soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2012, 47, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahram, M.; Põlme, S.; Kõljalg, U.; Zarre, S.; Tedersoo, L. Regional and local patterns of ectomycorrhizal fungal diversity and community structure along an altitudinal gradient in the Hyrcanian forests of northern Iran. New Phytol. 2012, 193, 465–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tedersoo, L.; Bahram, M.; Põlme, S.; Kõljalg, U.; Yorou, N.S.; Wijesundera, R.; Ruiz, L.V.; Vasco-Palacios, A.M.; Thu, P.Q.; Suija, A. Global diversity and geography of soil fungi. Science 2014, 346, 6213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Shi, X.; Zheng, C.; Suter, H.; Huang, Z. Different responses of soil bacterial and fungal communities to nitrogen deposition in a subtropical forest. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 755, 142449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhtar, H.; Lin, C.-M.; Wunderlich, R.F.; Cheng, L.-C.; Ko, M.-C.; Lin, Y.-P. Climate and land cover shape the fungal community structure in topsoil. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 751, 141721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kujawska, M.B.; Rudawska, M.; Wilgan, R.; Leski, T. Similarities and differences among soil fungal assemblages in managed forests and formerly managed forest reserves. Forests 2021, 12, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claridge, A.W.; Barry, S.C.; Cork, S.J.; James, M. Diversity and habitat relationships of hypogeous fungi. II. Factors influencing the occurrence and number of taxa. Biodivers. Conserv. 2000, 9, 175–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.D.; Durall, D.M.; Cairney, J.W.G. Ectomycorrhizal fungal communities in young forest stands regenerating after clearcut logging. New Phytol. 2003, 157, 399–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kernaghan, G.; Widden, P.; Bergeron, Y.; Légaré, S.; Paré, D. Biotic and abiotic factors affecting ectomycorrhizal diversity in boreal mixed-woods. Oikos 2003, 102, 497–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.E.; Douhan, G.W.; Fremier, A.K.; Rizzo, D.M. Are true multihost fungi the exception or the rule? Dominant ectomycorrhizal fungi on Pinus sabiniana differ from those on co-occurring Quercus species. New Phytol. 2009, 182, 295–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komura, D.L.; Moncalvo, J.M.; Dambros, C.S.; Bento, L.S.; Neves, M.A.; Charles, E.; Zartman, C.E. How do seasonality, substrate, and management history influence macrofungal fruiting assemblages in a central Amazonian Forest? Biotropica 2017, 49, 643–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olou, B.A.; Yorou, N.S.; Striegel, M.; Bässler, C.; Krah, F.S. Effects of macroclimate and resource on the diversity of tropical wood-inhabiting fungi. For. Ecol. Manag. 2019, 436, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepinay, C.; Jiráska, L.; Tláskal, V.; Brabcová, V.; Vrška, T.; Baldrian, T. Successional Development of Fungal Communities Associated with Decomposing Deadwood in a Natural Mixed Temperate Forest. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, W.; Cai, X.; Liu, X.; Wang, J.X.; Cheng, S.; Zhang, X.Y.; Li, D.Y.; Li, M.H. Soil microbial population dynamics along a chronosequence of moist evergreen broad-leaved forest succession in southwestern China. J. Mt. Sci. 2010, 7, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weand, M.P.; Arthur, M.A.; Lovett, G.M.; Sikora, F.; Weathers, K.C. The phosphorus status of northern hardwoods differs by species but is unaffected by nitrogen fertilization. Biogeochemistry 2010, 97, 159–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferris, R.; Peace, A.J.; Newton, A.C. Macrofungal communities of lowland Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) and Norway spruce (Picea abies (L.) Karsten.) plantations in England: Relationships with site factors and stand structure. For. Ecol. Manag. 2000, 131, 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.; Li, H.; Mortimer, P.E.; Xu, J.; Gui, H.; Karunarathna, S.C.; Kumar, A.; Hyde, K.D.; Shi, L. Substrate Preference Determines Macrofungal Biogeography in the Greater Mekong Sub-Region. Forests 2019, 10, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutszegi, G.; Siller, I.; Dima, B.; Merényi, Z.; Varga, T.; Takács, K.; Turcsányi, G.; Bidló, A.; Ódor, P. Revealing hidden drivers of macrofungal species richness by analyzing fungal guilds in temperate forests, West Hungary. Community Ecol. 2021, 22, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]