Insight into the Systematics of Microfungi Colonizing Dead Woody Twigs of Dodonaea viscosa in Honghe (China)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Herbarium Material and Fungal Strains

2.2. Morphological Observations

2.3. DNA Extraction, PCR Amplifications and Sequencing

2.4. Molecular Phylogenetic Analyses

2.4.1. Sequence Alignment

2.4.2. Phylogenetic Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Global Checklist of Fungi on Dodonaea Viscosa

3.2. Phylogenetic Analyses

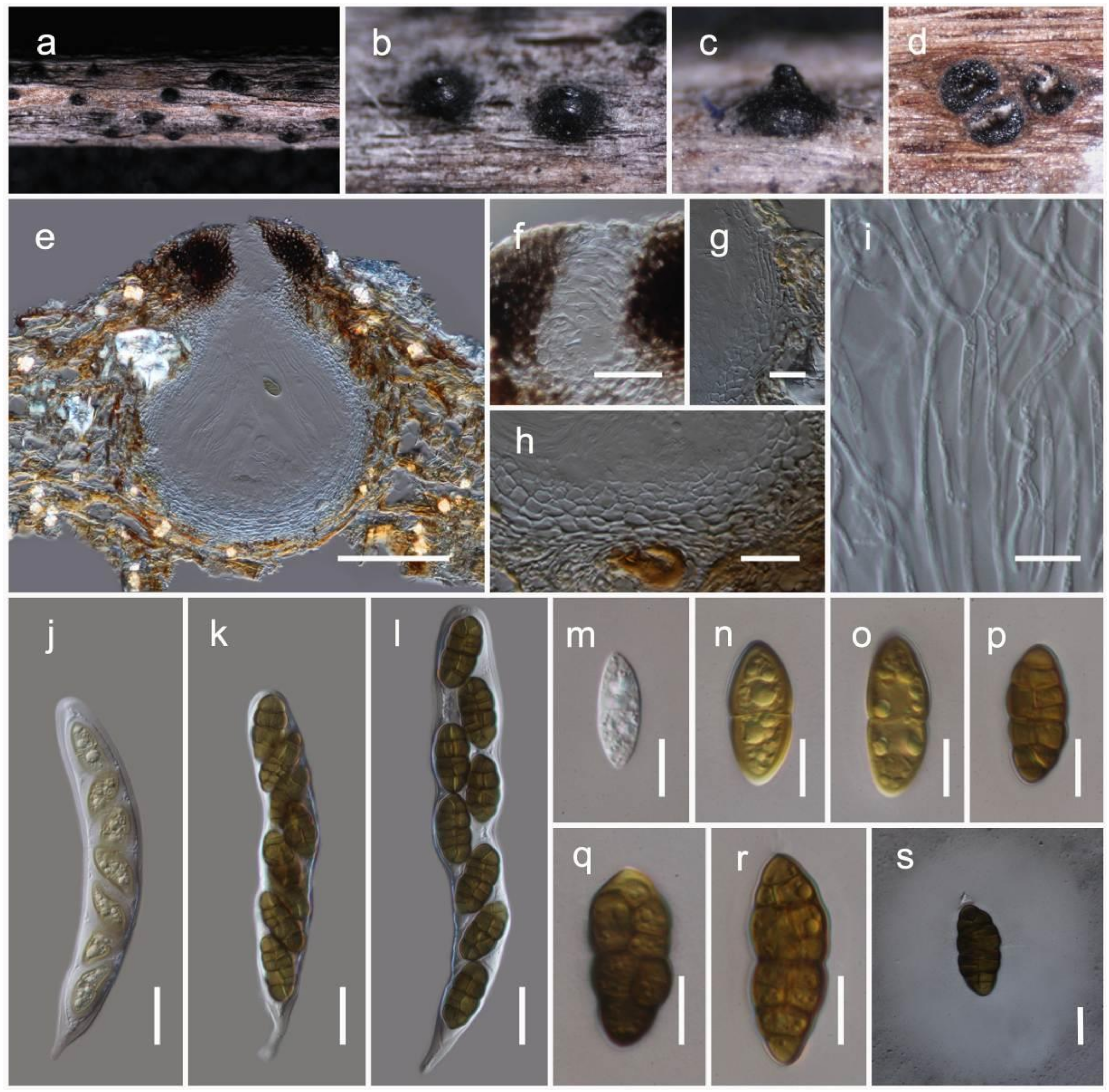

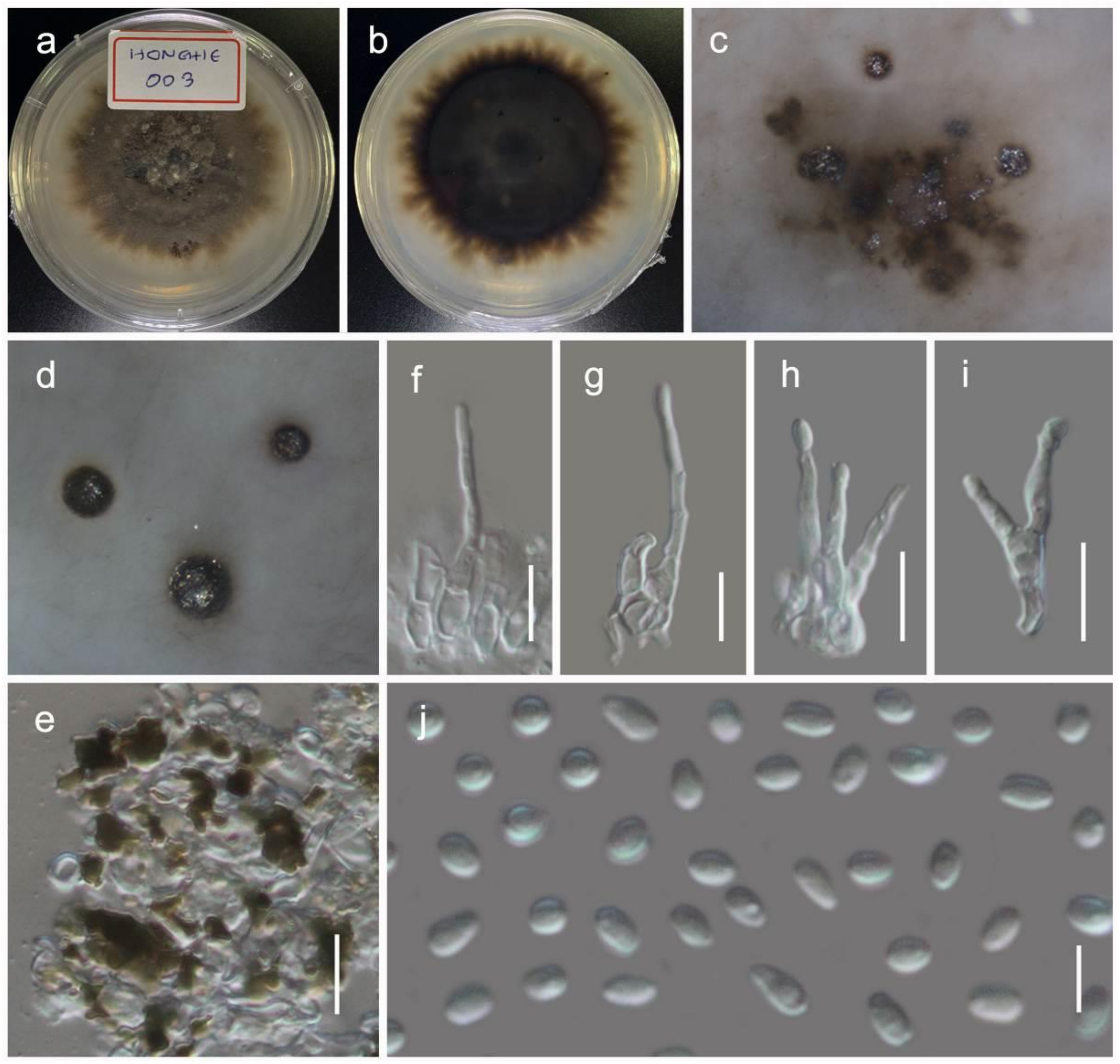

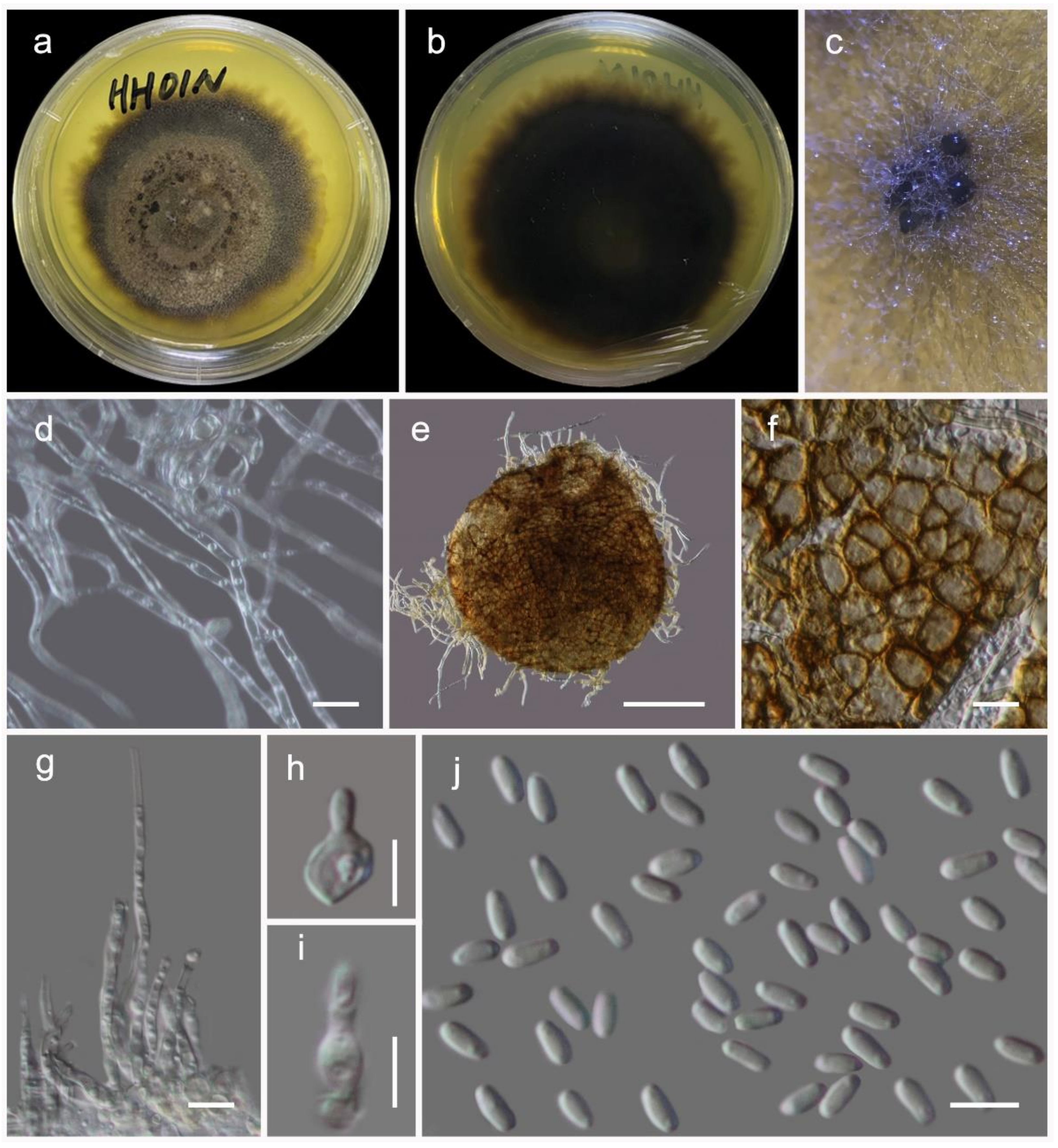

3.3. Taxonomy of Fungi Colonising Dodonaea Viscosa Twigs

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Antonelli, A.; Fry, C.; Smith, R.J.; Simmonds, M.S.J.; Kersey, P.J.; Pritchard, H.W.; Abbo, M.S.; Acedo, C.; Adams, J.; Ainsworth, A.M.; et al. State of the World’s Plants and Fungi 2020; Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew: Richmond, UK, 2020; 100p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, P.M. Catalogue of Life. Available online: http://www.catalogueoflife.org (accessed on 20 October 2020).

- Wijayawardene, N.N.; Hyde, K.D.; Al-Ani, L.K.T.; Tedersoo, L.; Haelewaters, D.; Rajeshkumar, K.C.; Zhao, R.L.; Aptroot, A.; Leontyev, D.V.; Saxena, R.K.; et al. Outline of Fungi and fungus-like taxa. Mycosphere 2020, 11, 1060–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawksworth, D.L.; Lücking, R. Fungal diversity revisited: 2.2 to 3.8 million species. Microbiol. Spectr. 2017, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, K.D.; Jeewon, R.; Chen, Y.J.; Bhunjun, C.S.; Calabon, M.S.; Jiang, H.B.; Lin, C.G.; Norphanphoun, C.; Sysouphanthong, P.; Pem, D.; et al. The numbers of fungi: Is the descriptive curve flattening? Fungal Divers. 2020, 103, 219–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, K.; Norphanphoun, C.; Chen, J.; Dissanayake, A.; Doilom, M.; Hongsanan, S.; Jayawardena, R.; Jeewon, R.; Perera, R.H.; Thongbai, B.; et al. Thailand’s amazing diversity: Up to 96% of fungi in northern Thailand may be novel. Fungal Divers. 2018, 93, 215–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, M.K.M.; Goh, T.K.; Hodgkiss, I.J.; Hyde, K.D.; Ranghoo, V.M.; Tsui, C.K.M.; Ho, W.W.H.; Wong, W.S.W.; Yuen, T.K. Role of fungi in freshwater ecosystems. Biodivers. Conserv. 1998, 7, 1187–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu-Qiang, S.; Xing-Jun, T.; Zhong-Qi, L.; Chang-Lin, Y.; Bin, C.; Jie-jie, H.; Jing, Z. Diversity of filamentous fungi in organic layers of two forests in Zijin Mountain. J. For. Res. 2004, 15, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Zheng, X.; Cheng, F.; Zhu, X.; Hou, L.; Li, J.; Zhang, S. Fungal community structure of fallen pine and oak wood at different stages of decomposition in the Qinling Mountains, China. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 13866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.C.; Zhao, R.L. The higher microfungi from forests of Yunnan Province; Yunnan Science and Technology Press: Kunming, China, 2012; pp. 1–572. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, X.K.; Chen, J.; Xu, M.J.; Lin, W.H.; Guo, S.X. Fungal endophytes associated with Sonneratia (Sonneratiaceae) mangrove plants on the south coast of China. For. Pathol. 2011, 41, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariyawansa, H.A.; Hyde, K.D.; Liu, J.K.; Wu, S.P.; Liu, Z.Y. Additions to karst fungi 1: Botryosphaeria minutispermatia sp. nov., from Guizhou Province, China. Phytotaxa 2016, 275, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariyawansa, H.A.; Hyde, K.D.; Tanaka, K.; Maharachchikumbura, S.S.N.; Al–Sadi, A.M.; Elgorban, A.M.; Liu, Z.Y. Additions to karst fungi 3: Prosthemium sinense sp. nov., from Guizhou province, China. Phytotaxa 2016, 284, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariyawansa, H.A.; Hyde, K.D.; Thambugala, K.M.; Maharachchikumbura, S.S.N.; Al–Sadi, A.M.; Liu, Z.Y. Additions to karst fungi 2: Alpestrisphaeria jonesii from Guizhou Province, China. Phytotaxa 2016, 277, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.M.; Cai, L.; Hyde, K.D. Three new ascomycetes from freshwater in China. Mycologia 2012, 104, 1478–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.F.; Liu, F.; Zhou, X.; Liu, X.Z.; Liu, S.J.; Cai, L. Culturable mycobiota from Karst caves in China, with descriptions of 20 new species. Persoonia Mol. Phylogeny Evol. Fungi 2017, 39, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De-Long, Q.; Liu, L.L.; Zhang, X.; Wen, T.C.; Kang, J.C.; Hyde, K.D.; Shen, X.C.; Li, Q.R. Contributions to species of Xylariales in China-1 Durotheca species. Mycol. Prog. 2019, 18, 495–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, D.F.; McKenzie, E.H.C.; Bhat, D.J.; Hyde, K.D.; Luo, Z.L.; Shen, H.W.; Su, H.Y. Acrogenospora (Acrogenosporaceae, Minutisphaerales) appears to be a very diverse genus. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karunarathna, S.C.; Dong, Y.; Karasaki, S.; Tibpromma, S.; Hyde, K.D.; Lumyong, S.; Xu, J.C.; Sheng, J.; Mortimer, P.E. Discovery of novel fungal species and pathogens on bat carcasses in a cave in Yunnan Province, China. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2020, 9, 1554–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, N.; Mittermeier, R.A.; Mittermeier, C.G.; da Fonseca, G.A.; Kent, J. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 2000, 403, 853–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.Y.; Shen, Q. Evaluation on landscape stability of Yuanyang Hani terrace. Yunnan Geogr. Environ. Res. 2011, 1, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shui, Y.M. Seed Plants of Honghe Region in SE Yunnan; Yunnan Science and Technology Press: Kunming, China, 2003; pp. 1–54. [Google Scholar]

- Ju, Y.; Zhuo, J.X.; Liu, B.; Long, C.L. Eating from the wild: Diversity of wild edible plants used by Tibetans in Shangri–la region, Yunnan, China. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2013, 1, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanasinghe, D.N.; Wijayawardene, N.N.; Xu, J.C.; Cheewangkoon, R.; Mortimer, P.E. Taxonomic novelties in Magnolia-associated pleosporalean fungi in the Kunming Botanical Gardens (Yunnan, China). PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0235855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marasinghe, D.S.; Samarakoon, M.C.; Hongsanan, S.; Boonmee, S.; Mckenzie, E.H.C. Iodosphaeria honghense sp. nov. (Iodosphaeriaceae, Xylariales) from Yunnan Province, China. Phytotaxa 2019, 420, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeki, H.F.; Ajmi, R.N.; Ati, E.M. Phytoremediation mechanisms of mercury (Hg) between some plants and soils in Baghdad City. Plant Arch. 2019, 19, 1395–1401. [Google Scholar]

- Beshah, F.; Hunde, Y.; Getachew, M.; Bachheti, R.K.; Husen, A.; Bachheti, A. Ethnopharmacological, phytochemistry and other potential applications of Dodonaea genus: A comprehensive review. Curr. Biotechnol. 2020, 2, 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, N.K.U.; Selvi, C.R.; Sasikala, V.; Dhanalakshmi, S.; Prakash, S.B.U. Phytochemistry and bio-efficacy of a weed, Dodonaea viscosa. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2012, 4, 509–512. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Snafi, P.A.E. A review on Dodonaea viscosa: A potential medicinal plant. IOSR J. Pharm. 2017, 7, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Aamri, K.K.; Hossain, M.A. New prenylated flavonoids from the leaves of Dodonaea viscosa native to the Sultanate of Oman. Pacific Science Review A. Nat. Sci. Eng. 2016, 18, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- AL-Oraimi, A.A.; Hossain, M.A. In vitro total flavonoids content and antimicrobial capacity of different organic crude extracts of D. viscosa. J. Biol. Active Prod. Nat. 2016, 6, 150–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christmas, M.J.; Biffin, E.; Lowe, A.J. Measuring genome–wide genetic variation to reassess subspecies classifications in Dodonaea viscosa (Sapindaceae). Aust. J. Bot. 2018, 66, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvam, V. Trees and Shrubs of the Maldives; FAO Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific, Thammada Press Co., Ltd.: Bangkok, Thailand, 2007; pp. 1–92. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Jobori, K.M.M.; Ali, S.A. Effect of Dodonaea viscosa Jacq. residues on growth and yield of mungbean (Vigna mungo L. Hepper). Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2014, 13, 2407–2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jobori, K.M.M.; Ali, S.A. Evaluation the effect of Dodonaea viscosa Jacq. residues on growth and yield of maize (Zea mays L.). Int. J. Adv. Res. 2014, 2, 514–521. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Obaidy, A.H.M.J.; Jasim, I.M.; Al–Kubaisi, A.R.A. Air pollution effects in some plant leaves morphological and anatomical characteristics within Baghdad City. Iraq. Eng. Technol. J. 2019, 37, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shtein, I.; Meir, S.; Riov, J.; Philosoph-hadas, S. Interconnection of seasonal temperature, vascular traits, leaf anatomy and hydraulic performance in cut Dodonaea ‘Dana’ branches. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2011, 61, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, M.S.; Pippalla, R.S.; Mohan, K. Dodonaea viscosa Linn-An overview. Asian J. Pharm. Res. Health Care 2009, 1, 97–112. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, M.A. Biological and phytochemicals review of Omani medicinal plant Dodonaea viscosa. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2019, 31, 1089–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanasinghe, D.N.; Mortimer, P.E.; Senwanna, C.; Cheewangkoon, R. Saprobic Dothideomycetes in Thailand: Phaeoseptum hydei sp. nov., a new terrestrial ascomycete in Phaeoseptaceae. Phytotaxa 2020, 449, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, I.; Kohn, L.M. A method for designing primer sets for speciation studies in filamentous ascomycetes. Mycologia 1999, 91, 553–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groenewald, J.Z.; Nakashima, C.; Nishikawa, J.; Shin, H.D.; Park, J.H.; Jama, A.N.; Groenewald, M.; Braun, U.; Crous, P.W. Species concepts in Cercospora: Spotting the weeds among the roses. Stud. Mycol. 2013, 75, 115–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woudenberg, J.H.; Aveskamp, M.M.; de Gruyter, J.; Spiers, A.G.; Crous, P.W. Multiple Didymella teleomorphs are linked to the Phoma clematidina morphotype. Persoonia 2009, 22, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaedvlieg, W.; Groenewald, J.Z.; de Jesús Yáñez-Morales, M.; Crous, P.W. DNA barcoding of Mycosphaerella species of quarantine importance to Europe. Persoonia 2012, 29, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, T.J.; Bruns, T.; Lee, S.J.W.T.; Taylor, J.W. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. PCR Protocols Appl. 1990, 18, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehner, S.A.; Samuels, G.J. Taxonomy and phylogeny of Gliocladium analysed from nuclear large subunit ribosomal DNA sequences. Mycol. Res. 1994, 98, 625–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilgalys, R.; Hester, M. Rapid genetic identification and mapping of enzymatically amplified ribosomal DNA from several Cryptococcus species. J. Bacteriol 1990, 172, 4238–4246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, G.H.; Sung, J.M.; Hywel-Jones, N.L.; Spatafora, J.W. A multi-gene phylogeny of Clavicipitaceae (Ascomycota, Fungi): Identification of localized incongruence using a combinational bootstrap approach. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2007, 44, 1204–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaedvlieg, W.; Binder, M.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Summerell, B.A.; Carnegie, A.J.; Burgess, T.I.; Crous, P.W. Introducing the Consolidated Species Concept to resolve species in the Teratosphaeriaceae. Persoonia 2014, 33, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehner, S.A.; Buckley, E. A Beauveria phylogeny inferred from nuclear ITS and EF1-α sequences: Evidence for cryptic diversification and links to Cordyceps teleomorphs. Mycologia 2005, 97, 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.J.; Whelen, S.; Hall, B.D. Phylogenetic relationships among ascomycetes evidence from an RNA polymerase II subunit. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1999, 16, 1799–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, K.; Kistler, H.C.; Cigelnik, E.; Ploetz, R.C. Multiple evolutionary origins of the fungus causing Panama disease of banana: Concordant evidence from nuclear and mitochondrial gene genealogies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 2044–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela-Lopez, N.; Cano-Lira, J.F.; Guarro, J.; Sutton, D.A.; Wiederhold, N.; Crous, P.W.; Stchigel, A.M. Coelomycetous Dothideomycetes with emphasis on the families Cucurbitariaceae and Didymellaceae. Stud. Mycol. 2018, 90, 1–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharachchikumbura, S.S.N.; Wanasinghe, D.N.; Cheewangkoon, R.; Al-Sadi, A.M. Uncovering the hidden taxonomic diversity of fungi in Oman. Fungal Divers. 2021, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mapook, A.; Hyde, K.D.; McKenzie, E.H.C.; Jones, E.B.G.; Bhat, D.J.; Jeewon, R.; Stadler, M.; Samarakoon, M.C.; Malaithong, M.; Tanunchai, B.; et al. Taxonomic and phylogenetic contributions to fungi associated with the invasive weed Chromolaena odorata (Siam weed). Fungal Divers. 2020, 101, 1–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, K.D.; Dong, Y.; Phookamsak, R.; Jeewon, R.; Bhat, D.J.; Jones, E.; Liu, N.; Abeywickrama, P.D.; Mapook, A.; Wei, D.; et al. Fungal diversity notes 1151–1276: Taxonomic and phylogenetic contributions on genera and species of fungal taxa. Fungal Divers. 2020, 100, 5–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuraku, S.; Zmasek, C.M.; Nishimura, O.; Katoh, K. aLeaves facilitates on-demand exploration of metazoan gene family trees on MAFFT sequence alignment server with enhanced interactivity. Nucleic Acids Res 2013, 41, W22–W28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, k.; Rozewicki, J.; Yamada, K.D. MAFFT online service: Multiple sequence alignment, interactive sequence choice and visualization. Brief. Bioinform. 2019, 20, 1160–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, T.A. BioEdit: A user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucl. Acids Symp. Ser. 1999, 41, 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Nylander, J.A.A.; Wilgenbusch, J.C.; Warren, D.L.; Swofford, D.L. AWTY (are we there yet?): A system for graphical exploration of MCMC convergence in Bayesian phylogenetics. Bioinformatics 2008, 24, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.A.; Pfeiffer, W.; Schwartz, T. Creating the CIPRES Science Gateway for inference of large phylogenetic trees. In Proceedings of the 2010 Gateway Computing Environments Workshop (GCE), New Orleans, LA, USA, 14 November 2010; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamatakis, A. RAxML version 8: A tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 1312–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambaut, A. FigTree Version 1.4.0. Available online: http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/ (accessed on 8 November 2020).

- Farr, D.F.; Rossman, A.Y. Fungal Databases, U.S. National Fungus Collections, ARS, USDA. Available online: https://nt.ars-grin.gov/fungaldatabases/ (accessed on 22 February 2021).

- Burgess, T.I.; Tan, Y.P.; Garnas, J.; Edwards, J.; Scarlett, K.A.; Shuttleworth, L.A.; Daniel, R.; Dann, E.K.; Parkinson, L.E.; Dinh, Q.; et al. Current status of the Botryosphaeriaceae in Australia. Australas. Plant Pathol. 2019, 48, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, R.S. The Coelomycetes of India; Bishen Singh Mahendra Pal Singh: Delhi, India, 1979; 460p. [Google Scholar]

- Vandemark, G.J.; Martinez, O.; Pecina, V.; Alvarado, M. Assessment of genetic relationships among isolates of Macrophomina phaseolina using a simplified AFLP technique and two different methods of analysis. Mycologia 2000, 92, 656–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dingley, J.M.; Fullerton, R.A.; McKenzie, E.H.C. Survey of Agricultural Pests and Diseases; Technical Report Volume 2: Records of Fungi, Bacteria, Algae, and Angiosperms Pathogenic on Plants in Cook Islands, Fiji, Kiribati, Niue, Tonga, Tuvalu, and Western Samoa; FAO: Rome, Italy, 1981; 485p, p. 485. [Google Scholar]

- Kamal. Cercosporoid Fungi of INDIA; Bishen Singh Mahendra Pal Singh: Dehra Dun, India, 2010; 351p. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, R.K.; Srivastava, N.; Srivastava, A.K. Additions to genus Cercospora from North-Eastern Uttar Pradesh. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. India 1994, 64, 105–114. [Google Scholar]

- Crous, P.W.; Braun, U. Mycosphaerella and Its Anamorphs: 1. Names Published in Cercospora and Passalora; Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2003; 571p. [Google Scholar]

- Deighton, F.C. Preliminary list of fungi and diseases of plants in Sierra Leone and list of fungi collected in Sierra Leone. Bull. Misc. Inf. 1936, 1936, 397–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennycook, S.R. Plant Diseases Recorded in New Zealand; 3 Vol. Pl. Dis. Div.; D.S.I.R.: Auckland, New Zealand, 1989; 958p. [Google Scholar]

- Gadgil, P.D. Fungi on Trees and Shrubs in New Zealand; Fungi of New Zealand (Volume 4); Fungal Diversity Press: Hong Kong, 2005; 437p. [Google Scholar]

- Alfieri, S.A., Jr.; Langdon, K.R.; Wehlburg, C.; Kimbrough, J.W. Index of Plant Diseases in Florida (Revised). Fla. Dept. Agric. Consum. Serv. Div. Plant Ind. Bull. 1984, 11, 1–389. [Google Scholar]

- Boesewinkel, H.J. Pseudocercospora dodonaeae sp. nov. and a note on powdery mildew of Dodonaea in New Zealand. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 1981, 77, 453–455. [Google Scholar]

- De Miranda, B.E.C.; Ferreira, B.W.; Alves, J.L.; de Macedo, D.M.; Barreto, R.W. Pseudocercospora lonicerigena a leaf spot fungus on the invasive weed Lonicera japonica in Brazil. Australas. Plant Pathol. 2014, 43, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio, J.A.; Wingfield, M.J.; De Beer, Z.W.; Roux, J. Pseudocercospora mapelanensis sp. nov., associated with a fruit and leaf disease of Barringtonia racemosa in South Africa. Australas. Plant Pathol. 2015, 44, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.J.; Guo, Y.L. (Eds.) Flora Fungorum Sinicorum; Vol. 9. Pseudocercospora; Science Press: Beijing, China, 1998; 474p. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, S.; Iqbal, S.H.; Khalid, A.N. Fungi of Pakistan; Sultan Ahmad Mycological Society of Pakistan: Lahore, Pakistan, 1997; p. 248. [Google Scholar]

- Ciferri, R. Mycoflora Domingensis Integrata. Quaderno 1961, 19, 1–539. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis, R.W.G. Fungus Flora of Venezuela and Adjacent Countries; Kew Bulletin Additional Series III; Verlag von J. Cramer: Weinheim, Germany, 1970; p. 531. [Google Scholar]

- Farr, M.L.; Schoknecht, J.D.; Crane, J.L. A Costa Rican black mildew found in Everglades National Park, Florida. Can. J. Bot. 2011, 63, 1983–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urtiaga, R. Host index of plant diseases and disorders from Venezuela—Addendum. Unknown journal or publisher. 2004. 268p.

- Singh, K.P.; Shukla, R.S.; Kumar, S.; Hussain, A. A leaf-spot disease of Dodonaea viscosa caused by Corynespora cassiicola in India. Indian Phytopathol. 1982, 35, 325. [Google Scholar]

- Castellani, E.; Ciferri, R. Prodromus Mycoflorae Africae Orientalis Italicae; Istituto Agricolo Coloniale Italiano: Firenze, Italy, 1937; 167p. [Google Scholar]

- Georghiou, G.P.; Papadopoulos, C. A Second List of Cyprus Fungi; Government of Cyprus, Department of Agriculture: Nicosia, Cyprus, 1957; 38p.

- Sarbhoy, A.K.; Lal, G.; Varshney, J.L. Fungi of India (1967–71); Navyug Traders: New Delhi, India, 1971; 148p. [Google Scholar]

- Pande, A. Ascomycetes of Peninsular India; Scientific Publishers (India): Jodhpur, India, 2008; 584p. [Google Scholar]

- Amano, K. (Hirata) Host Range and Geographical Distribution of the Powdery Mildew Fungi; Japan Sci. Soc. Press: Tokyo, Japan, 1986; 741p. [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside, J.O. A revised list of plant diseases in Rhodesia. Kirkia 1966, 5, 87–196. [Google Scholar]

- Castellani, E.; Ciferri, R. Mycoflora Erythraea, Somala et Aethipica Suppl; 1. Atti Ist. Bot. Lab. Crittog. Univ.: Pavia, Italy, 1950; 52p. [Google Scholar]

- Boesewinkel, H.J. Erysiphaceae of New Zealand. Sydowia 1979, 32, 13–56. [Google Scholar]

- Doidge, E.M. The South African fungi and lichens to the end of 1945. Bothalia 1950, 5, 1–1094. [Google Scholar]

- French, A.M. California Plant Disease Host Index; Calif. Dept. Food Agric.: Sacramento, CA, USA, 1989; 394p. [Google Scholar]

- Hansford, C.G. The Meliolineae. A monograph. Beih. Sydowia 1961, 2, 1–806. [Google Scholar]

- Goos, R.D.; Anderson, J.H. The Meliolaceae of Hawaii. Sydowia 1972, 26, 73–80. [Google Scholar]

- Raabe, R.D.; Conners, I.L.; Martinez, A.P. Checklist of Plant Diseases in Hawaii; College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resources, University of Hawaii. Information Text Series No. 22; Hawaii Inst. Trop. Agric. Human Resources: Honolulu, HI, USA, 1981; 313p. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, F.L. Hawaiian Fungi. Bernice P. Bishop Mus. Bull. 1925, 19, 1–189. [Google Scholar]

- Crous, P.W. Taxonomy and Pathology of Cylindrocladium (Calonectria) and Allied Genera; American Phytopathological Society: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2002; 278p. [Google Scholar]

- Schoch, C.L.; Crous, P.W.; Cronwright, G.; El-Gholl, N.E.; Wingfield, B.D. Recombination in Calonectria morganii and phylogeny with other heterothallic small-spored Calonectria species. Mycologia 2000, 92, 665–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polizzi, G.; Catara, V. First report of leaf spot caused by Cylindrocladium pauciramosum on Acacia retinodes, Arbutus unedo, Feijoa sellowiana and Dodonaea viscosa in southern Italy. Plant Dis. 2001, 85, 803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlach, W.; Ershad, D. Beitrag zur Kenntnis der Fusarium—Und Cylindrocarpon-Arten in Iran. Nova Hedwigia 1970, 20, 725–784. [Google Scholar]

- Tilak, S.; Rao, R. Contribution to our knowledge of ascomycetes of India. V. Mycopathol. Mycol. Appl. 1966, 28, 90–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostert, L.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Summerbell, R.C.; Robert, V.; Sutton, D.A.; Padhye, A.A.; Crous, P.W. Species of Phaeoacremonium associated with infection in humans and environmental reservoirs in infected woody plants. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2005, 43, 1752–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostert, L.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Summerbell, R.C.; Gams, W.; Crous, P.W. Taxonomy and pathology of Togninia (Diaporthales) and its Phaeoacremonium anamorphs. Stud. Mycol. 2006, 54, 1–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gramaje, D.; Mostert, L.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Crous, P.W. Phaeoacremonium: From esca disease to phaeohyphomycosis. Fungal Biol. 2015, 119, 759–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gramaje, D.; Leon, M.; Perez-Sierra, A.; Burgess, T.; Armengol, J. New Phaeoacremonium species isolated from sandalwood trees in Western Australia. IMA Fungus 2014, 5, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spies, C.F.J.; Moyo, P.; Halleen, F.; Mostert, L. Phaeoacremonium species diversity on woody hosts in the Western Cape Province of South Africa. Persoonia 2018, 40, 26–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbertson, R.L.; Bigelow, D.M.; Hemmes, D.E.; Desjardin, D.E. Annotated check list of Wood-Rotting Basidiomycetes of Hawaii. Mycotaxon 2002, 82, 215–239. [Google Scholar]

- Nakasone, K.K.; Burdsall, H.H., Jr. The genus Dendrothele (Agaricales, Basidiomycota) in New Zealand. N. Z. J. Bot. 2011, 49, 107–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiello, D.; Guarnaccia, V.; Formica, P.T.; Hyakumachi, M.; Polizzi, G. Occurence and characterisation of Rhizoctonia species causing diseases of ornamental plants in Italy. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2017, 148, 967–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pildain, M.B.; Perez, G.A.; Robledo, G.; Pappano, D.B.; Rajchenberg, M. Arambarria the pathogen involved in canker rot of Eucalyptus, native trees wood rots and grapevine diseases in the southern hemisphere. For. Pathol. 2017, 47, e12397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, M.; Edwards, J.; Cunnington, J.H.; Pascoe, I.G. Basidiomycetous pathogens on grapevine: A new species from Australia—Fomitiporia australiensis. Mycotaxon 2005, 92, 85–96. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbertson, R.L.; Martin, K.J.; Lindsey, J.P. Annotated Check List and Host Index for Arizona Wood-Rotting Fungi; College of Agriculture, University of Arizona: Tucson, AZ, USA, 1974; Volume 209, pp. 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbertson, R.L. The genus Phellinus (Aphyllophorales: Hymenochaetaceae) in western North America. Mycotaxon 1979, 9, 51–89. [Google Scholar]

- Boedijn, K.B. The Uredinales of Indonesia. Nova Hedwigia 1959, 1, 463–496. [Google Scholar]

- Hardy, G.E.; Sivasithamparam, K. Phytophthora spp. associated with container- grown plants in nurseries in Western Australia. Plant Dis. 1988, 72, 435–437. [Google Scholar]

- Shivas, R.G. Fungal and bacterial diseases of plants in Western Australia. J. R. Soc. West. Aust. 1989, 72, 1–62. [Google Scholar]

- Erwin, D.C.; Ribeiro, O.K. Phytophthora Diseases Worldwide; APS Press: St. Paul, MN, USA, 1996; 562p. [Google Scholar]

- Mammella, M.A.; Cacciola, S.O.; Martin, F.; Schena, L. Genetic characterization of Phytophthora nicotianae by the analysis of polymorphic regions of the mitochondrial DNA. Fungal Biol. 2011, 115, 432–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mammella, M.A.; Martin, F.N.; Cacciola, S.O.; Coffey, M.D.; Faedda, R.; Schena, L. Analyses of the population structure in a global collection of Phytophthora nicotianae isolates inferred from mitochondrial and nuclear DNA sequences. Phytopathology 2013, 103, 610–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, T.; Orlikowski, L.; Henricot, B.; Abad-Campos, P.; Aday, A.G.; Aguin Casal, O.; Bakonyi, J.; Cacciola, S.O.; Cech, T.; Chavarriaga, D.; et al. Widespread Phytophthora infestations in European nurseries put forest, semi-natural and horticultural ecosystems at high risk of Phytophthora diseases. For. Pathol. 2016, 46, 134–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crous, P.W.; Schoch, C.L.; Hyde, K.D.; Wood, A.R.; Gueidan, C.; de Hoog, G.S.; Groenewald, J.Z. Phylogenetic lineages in the Capnodiales. Stud. Mycol. 2009, 64, 17–4757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Videira, S.I.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Braun, U.; Shin, H.D.; Crous, P.W. All that glitters is not Ramularia. Stud. Mycol. 2016, 83, 49–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crous, P.W.; Carnegie, A.J.; Wingfield, M.J.; Sharma, R.; Mughini, G.; Noordeloos, M.E.; Santini, A.; Shouche, Y.S.; Bezerra, J.D.P.; Dima, B.; et al. Fungal Planet description sheets: 868–950. Persoonia 2019, 42, 291–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasiri, S.C.; Hyde, K.D.; Jones, E.B.G.; McKenzie, E.H.C.; Jeewon, R.; Phillips, A.J.L.; Bhat, D.J.; Wanasinghe, D.N.; Liu, J.K.; Lu, Y.Z.; et al. Diversity, morphology and molecular phylogeny of Dothideomycetes on decaying wild seed pods and fruits. Mycosphere 2019, 10, 1–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Gong, G.; Zhang, S.; Liu, N.; Wand, L.; Li, P.; Yu, X. A new species of the genus Trematosphaeria from China. Mycol Prog. 2014, 13, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thambugala, K.M.; Hyde, K.D.; Tanaka, K.; Tian, Q.; Wanasinghe, D.N.; Ariyawansa, H.A.; Jayasiri, S.C.; Boonmee, S.; Camporesi, E.; Hashimoto, A.; et al. Towards a natural classification and backbone tree for Lophiostomataceae, Floricolaceae, and Amorosiaceae fam. nov. Fungal Divers. 2015, 74, 199–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanasinghe, D.N.; Phukhamsakda, C.; Hyde, K.D.; Jeewon, R.; Lee, H.B.; Jones, E.B.G.; Tibpromma, S.; Tennakoon, D.S.; Dissanayake, A.J.; Jayasiri, S.C.; et al. Fungal diversity notes 709–839: Taxonomic and phylogenetic contributions to fungal taxa with an emphasis on fungi on Rosaceae. Fungal Divers. 2018, 89, 1–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crous, P.W.; Wingfield, M.J.; Burgess, T.I.; Hardy, G.; Gené, J.; Guarro, J.; Baseia, I.G.; García, D.; Gusmão, L.; Souza-Motta, C.M. Fungal Planet description sheets: 716–784. Persoonia 2018, 40, 239–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Ortega, S.; Garrido-Benavent, I.; De Los Rios, A. Austrostigmidium, a new austral genus of lichenicolous fungi close to rock-inhabiting meristematic fungi in Teratosphaeriaceae. Lichenologist 2015, 47, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirayama, K.; Tanaka, K. Taxonomic revision of Lophiostoma and Lophiotrema based on reevaluation of morphological characters and molecular analyses. Mycoscience 2011, 52, 401–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanasinghe, D.N.; Hyde, K.D.; Jeewon, R.; Crous, P.W.; Wijayawardene, N.N.; Jones, E.B.G.; Bhat, D.J.; Phillips, A.J.L.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Dayarathne, M.C.; et al. Phylogenetic revision of Camarosporium (Pleosporineae, Dothideomycetes) and allied genera. Stud. Mycol. 2017, 87, 207–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoch, C.L.; Shoemaker, R.A.; Seifert, K.A.; Hambleton, S.; Spatafora, J.W.; Crous, P.W. A multigene phylogeny of the Dothideomycetes using four nuclear loci. Mycologia 2006, 98, 1041–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crous, P.W.; Tanaka, K.; Summerell, B.A.; Groenewald, J.Z. Additions to the Mycosphaerella complex. IMA Fungus 2011, 2, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.K.; Hyde, K.D.; Jones, E.B.G.; Ariyawansa, H.A.; Bhat, D.J.; Boonmee, S.; Maharachchikumbura, S.S.N.; Mckenzie, E.H.C.; Phookamsak, R.; Phukhamsakda, C.; et al. Fungal diversity notes 1–110: Taxonomic and phylogenetic contributions to fungal species. Fungal Divers. 2015, 72, 1–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkley, G.J.; Dukik, K.; Renfurm, R.; Goker, M.; Stielow, J.B. Novel genera and species of coniothyrium-like fungi in Montagnulaceae (Ascomycota). Persoonia 2014, 32, 25–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egidi, E.; De Hoog, G.S.; Isola, D.; Onofri, S.; Quaedvlieg, W.; De Vries, M.; Verkley, G.J.M.; Stielow, J.B.; Zucconi, L.; Selbmann, L. Phylogeny and taxonomy of meristematic rock–inhabiting black fungi in the Dothideomycetes based on multi–locus phylogenies. Fungal Divers. 2014, 65, 127–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, A.; Hirayama, K.; Takahashi, H.; Matsumura, M.; Okada, G.; Chen, C.Y.; Huang, J.W.; Kakishima, M.; Ono, T.; Tanaka, K. Resolving the Lophiostoma bipolare complex: Generic delimitations within Lophiostomataceae. Stud. Mycol. 2018, 90, 161–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crous, P.W.; Summerell, B.A.; Shivas, R.G.; Burgess, T.I.; Decock, C.A.; Dreyer, L.L.; Granke, L.L.; Guest, D.I.; Hardy, G.E.; Hausbeck, M.K.; et al. Fungal Planet description sheets: 107–127. Persoonia 2012, 28, 138–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoch, C.L.; Crous, P.W.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Boehm, E.W.; Burgess, T.I.; de Gruyter, J.; de Hoog, G.S.; Dixon, L.J.; Grube, M.; Gueidan, C.; et al. A class-wide phylogenetic assessment of Dothideomycetes. Stud. Mycol. 2009, 64, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crous, P.W.; Wingfield, M.J.; Guarro, J.; Cheewangkoon, R.; van der Bank, M.; Swart, W.J.; Stchigel, A.M.; Cano-Lira, J.F.; Roux, J.; Madrid, H.; et al. Fungal Planet description sheets: 154–213. Persoonia 2013, 31, 188–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selbmann, L.; de Hoog, G.S.; Zucconi, L.; Isola, D.; Ruisi, S.; van den Ende, A.H.; Ruibal, C.; De Leo, F.; Urzì, C.; Onofri, S. Drought meets acid: Three new genera in a dothidealean clade of extremotolerant fungi. Stud Mycol. 2008, 61, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, D.F.; Su, H.Y.; Maharachchikumbura, S.S.N.; Liu, J.K.; Nalumpang, S.; Luo, Z.L.; Hyde, K.D. Lignicolous freshwater fungi from China and Thailand: Multi-gene phylogeny reveals new species and new records in Lophiostomataceae. Mycosphere 2019, 10, 1080–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phukhamsakda, C.; Ariyawansa, H.A.; Phillips, A.L.J.; Wanasinghe, D.N.; Bhat, D.J.; McKenzie, E.H.C.; Singtripop, C.; Camporesi, E.; Hyde, K.D. Additions to Sporormiaceae: Introducing Two Novel Genera, Sparticola and Forliomyces, from Spartium. Cryptogam. Mycol. 2016, 37, 75–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, K.; Hongsanan, S.; Jeewon, R.; Bhat, D.J.; Mckenzie, E.; Jones, E.; Phookamsak, R.; Ariyawansa, H.; Boonmee, S.; Zhao, Q. Fungal diversity notes 367–490: Taxonomic and phylogenetic contributions to fungal taxa. Fungal Divers. 2016, 80, 1–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, K.D.; de Silva, N.I.; Jeewon, R.; Bhat, D.J.; Phookamsak, R.; Doilom, M.; Boonmee, S.; Jayawardena, R.S.; Maharachchikumbura, S.S.N.; Senanayake, I.C.; et al. AJOM new records and collections of fungi: 1–100. AJOM 2020, 3, 22–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehm, E.W.; Schoch, C.L.; Spatafora, J.W. On the evolution of the Hysteriaceae and Mytilinidiaceae (Pleosporomycetidae, Dothideomycetes, Ascomycota) using four nuclear genes. Mycol. Res. 2009, 113, 461–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasiri, S.C.; Hyde, K.D.; Jones, E.B.G.; Persoh, D.; Camporesi, E.; Kang, J.C. Taxonomic novelties of hysteriform Dothideomycetes. Mycosphere 2018, 9, 803–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phookamsak, R.; Hyde, K.; Jeewon, R.; Bhat, D.J.; Jones, E.; Maharachchikumbura, S.; Raspé, O.; Karunarathna, S.; Wanasinghe, D.N.; Hongsanan, S.; et al. Fungal diversity notes 929–1035: Taxonomic and phylogenetic contributions on genera and species of fungi. Fungal Divers. 2019, 95, 1–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crous, P.W.; Wingfield, M.J.; Burgess, T.I.; Hardy, G.E.; Crane, C.; Barrett, S.; Cano-Lira, J.F.; Le Roux, J.J.; Thangavel, R.; Guarro, J.; et al. Fungal Planet description sheets: 469–557. Persoonia 2016, 37, 218–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Gruyter, J.; Woudenberg, J.H.C.; Aveskamp, M.M.; Verkley, G.J.M.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Crous, P.W. Redisposition of phoma–like anamorphs in Pleosporales. Stud. Mycol. 2013, 75, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, D.; Groenewald, M.; de Vries, M.; Gehrmann, T.; Stielow, B.; Eberhardt, U.; Al-Hatmi, A.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Cardinali, G.; Houbraken, J.; et al. Large-scale generation and analysis of filamentous fungal DNA barcodes boosts coverage for kingdom fungi and reveals thresholds for fungal species and higher taxon delimitation. Stud. Mycol. 2019, 92, 135–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariyawansa, H.A.; Hyde, K.D.; Jayasiri, S.C.; Buyck, B.; Chethana, K.W.T.; Dai, D.Q.; Dai, Y.C.; Daranagama, D.A.; Jayawardena, R.S.; Lücking, R.; et al. Fungal diversity notes 111–252—taxonomic and phylogenetic contributions to fungal taxa. Fungal Divers. 2015, 75, 27–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoch, C.L.; Seifertb, K.A.; Huhndorfc, S.; Robertd, V.; Spougea, J.L.; Levesqueb, C.A.; Chenb, W. Nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region as a universal DNA barcode marker for Fungi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 6241–6246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, K.; Hirayama, K.; Yonezawa, H.; Sato, G.; Toriyabe, A.; Kudo, H.; Hashimoto, A.; Matsumura, M.; Harada, Y.; Kurihara, Y.; et al. Revision of the Massarineae (Pleosporales, Dothideomycetes). Stud. Mycol. 2015, 82, 75–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.K.; Fournier, J.; Crous, P.W.; Jeewon, R.; Pointing, S.B.; Hyde, K.D. Towards a phylogenetic clarification of Lophiostoma/Massarina and morphologically similar genera in the Pleosporales. Fungal Divers. 2009, 38, 225–251. [Google Scholar]

- Liew, E.C.; Aptroot, A.; Hyde, K.D. An evaluation of the monophyly of Massarina based on ribosomal DNA sequences. Mycologia 2002, 94, 803–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jaklitsch, W.M.; Checa, J.; Blanco, M.N.; Olariaga, I.; Tello, S.; Voglmayr, H. A preliminary account of the Cucurbitariaceae. Stud. Mycol. 2018, 90, 71–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanasinghe, D.N.; Camporesi, E.; Hu, D.M. Neoleptosphaeria jonesii sp. nov., a novel saprobic sexual species, in Leptosphaeriaceae. Mycosphere 2016, 7, 1368–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Gruyter, J.; Aveskamp, M.M.; Woudenberg, J.H.; Verkley, G.J.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Crous, P.W. Molecular phylogeny of Phoma and allied anamorph genera: Towards a reclassification of the Phoma complex. Mycol. Res. 2009, 113, 508–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, K.D.; Chaiwan, N.; Norphanphoun, C.; Boonmee, S.; Camporesi, E.; Chethana, K.W.T.; Dayarathne, M.C.; de Silva, N.I.; Dissanayake, A.J.; Ekanayaka, A.H.; et al. Mycosphere notes 169–224. Mycosphere 2018, 9, 271–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Gruyter, J.; Woudenberg, J.H.; Aveskamp, M.M.; Verkley, G.J.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Crous, P.W. Systematic reappraisal of species in Phoma section Paraphoma, Pyrenochaeta and Pleurophoma. Mycologia 2010, 102, 1066–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marincowitz, S.; Crous, P.W.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Wingfield, M.J. Microfungi Occurring on Proteaceae in the Fynbos; CBS Biodiversity Series; Evolutionary Phytopathology, CBS Fungal Biodiversity Centre: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 1–166. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.J.; McKenzie, E.H.; Liu, J.K.J.; Bhat, D.J.; Dai, D.Q.; Camporesi, E.; Tian, Q.; Maharachchikumbura, S.S.N.; Luo, Z.L.; Shang, Q.J.; et al. Taxonomy and phylogeny of hyaline–spored coelomycetes. Fungal Divers. 2020, 100, 279–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phukhamsakda, C.; McKenzie, E.H.C.; Phillips, A.J.L.; Jones, E.B.G.; Bhat, D.J.; Stadler, M.; Bhunjun, C.S.; Wanasinghe, D.N.; Thongbai, B.; Camporesi, E.; et al. Microfungi associated with Clematis (Ranunculaceae) with an integrated approach to delimiting species boundaries. Fungal Divers. 2020, 102, 1–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.J.; Hyde, K.D.; Zhao, R.L.; Hongsanan, S.; Abdel–Aziz, F.A.; Abdel–Wahab, M.A.; Alvarado, P.; Alves–Silva, G.; Ammirati, J.F.; Ariyawansa, H.A.; et al. Fungal diversity notes 253–366: Taxonomic and phylogenetic contributions to fungal taxa. Fungal Divers. 2016, 78, 1–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, K.D.; Norphanphoun, C.; Abreu, V.P.; Bazzicalupo, A.; Chethana, K.W.T.; Clericuzio, M.; Dayarathne, M.C.; Dissanayake, A.J.; Ekanayaka, A.H.; He, M.; et al. Fungal diversity notes 603–708: Taxonomic and phylogenetic notes on genera and species. Fungal Divers. 2017, 87, 1–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crous, P.W.; Summerell, B.A.; Shivas, R.G.; Romberg, M.; Mel’nik, V.A.; Verkley, G.J.; Groenewald, J.Z. Fungal Planet description sheets: 92–106. Persoonia 2011, 27, 130–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, A.P.M.; Attili–Angelis, D.; Baron, N.C.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Crous, P.W.; Pagnocca, F.C. Riding with the ants. Persoonia 2017, 38, 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayarathne, M.C.; Jones, E.B.G.; Maharachchikumbura, S.S.N.; Devadatha, B.; Sarma, V.V.; Khongphinitbunjong, K.; Chomnunti, P.; Hyde, K.D. Morpho–molecular characterization of micro fungi associated with marine based habitats. Mycosphere 2020, 11, 1–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibpromma, S.; Hyde, K.D.; Jeewon, R.; Maharachchikumbura, S.S.N.; Liu, J.K.; Bhat, D.J.; Jones, E.B.G.; McKenzie, E.H.C.; Camporesi, E.; Bulgakov, T.S.; et al. Fungal diversity notes 491–602: Taxonomic and phylogenetic contributions to fungal taxa. Fungal Divers. 2017, 83, 1–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suetrong, S.; Schoch, C.L.; Spatafora, J.W.; Kohlmeyer, J.; Volkmann-Kohlmeyer, B.; Sakayaroj, J.; Phongpaichit, S.; Tanaka, K.; Hirayama, K.; Jones, E.B.G. Molecular systematics of the marine Dothideomycetes. Stud. Mycol. 2009, 64, 155–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crous, P.W.; Shivas, R.G.; Quaedvlieg, W.; van der Bank, M.; Zhang, Y.; Summerell, B.A.; Guarro, J.; Wingfield, M.J.; Wood, A.R.; Alfenas, A.C.; et al. Fungal Planet description sheets: 214–280. Persoonia 2014, 32, 184–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Nieuwenhuijzen, E.J.; Houbraken, J.A.M.P.; Punt, P.J.; Roeselers, G.; Adan, O.C.G.; Samson, R.A. The fungal composition of natural biofinishes on oil-treated wood. Fungal Biol Biotechnol. 2017, 4, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thambugala, K.M.; Hyde, K.D.; Eungwanichayapant, P.D.; Romero, A.I.; Liu, Z.Y. Additions to the genus Rhytidhysteron in Hysteriaceae. Cryptogam Mycol. 2016, 37, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Cheewangkoon, R.; Thambugala, K.M.; Jones, G.E.B.; Brahmanage, R.S.; Doilom, M.; Jeewon, R.; Hyde, K.D. Rhytidhysteron mangrovei (Hysteriaceae), a new species from mangroves in Phetchaburi Province, Thailand. Phytotaxa 2019, 401, 166–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugambi, G.K.; Huhndorf, S.M. Parallel evolution of hysterothecial ascomata in ascolocularous fungi (Ascomycota, Fungi). Syst. Biodivers. 2009, 7, 453–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, D.A.C.; Gusmao, L.F.P.; Miller, A.N. A new genus and three new species of hysteriaceous ascomycetes from the semiarid region of Brazil. Phytotaxa 2014, 176, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yacharoen, S.; Tian, Q.; Chomnunti, P.; Boonmee, S.; Chukeatirote, E.; Bhat, J.D.; Hyde, K.D. Patellariaceae revisited. Mycosphere 2015, 6, 290–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehm, E.W.; Mugambi, G.K.; Miller, A.N.; Huhndorf, S.M.; Marincowitz, S.; Spatafora, J.W.; Schoch, C.L. A molecular phylogenetic reappraisal of the Hysteriaceae, Mytilinidiaceae and Gloniaceae (Pleosporomycetidae, Dothideomycetes) with keys to world species. Stud. Mycol. 2009, 64, 49–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doilom, M.; Dissanayake, A.J.; Wanasinghe, D.N.; Boonmee, S.; Liu, J.K.; Bhat, D.J.; Taylor, J.E.; Bahkali, A.H.; McKenzie, E.H.C.; Hyde, K.D. Micro fungi on Tectona grandis (teak) in Northern Thailand. Fungal Divers. 2016, 82, 107–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaklitsch, W.M.; Olariaga, I.; Voglmayr, H. Teichospora and the Teichosporaceae. Mycol. Prog. 2016, 15, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanasinghe, D.N.; Jones, E.B.G.; Dissanayake, A.J.; Hyde, K.D. Saprobic Dothideomycetes in Thailand: Vaginatispora appendiculata sp. nov. (Lophiostomataceae) introduced based on morphological and molecular data. Stud. Fungi 2016, 1, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aveskamp, M.M.; de Gruyter, J.; Woudenberg, J.H.; Verkley, G.J.; Crous, P.W. Highlights of the Didymellaceae: A polyphasic approach to characterize Phoma and related pleosporalean genera. Stud. Mycol. 2010, 65, 1–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crous, P.W.; Braun, U.; Groenewald, J.Z. Mycosphaerella is polyphyletic. Stud. Mycol. 2007, 58, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hongsanan, S.; Hyde, K.D.; Phookamsak, R.; Wanasinghe, D.N.; McKenzie, E.H.C.; Sarma, V.V.; Boonmee, S.; Lücking, R.; Bhat, D.J.; Liu, N.G. Refined families of Dothideomycetes: Dothideomycetidae and Pleosporomycetidae. Mycosphere 2020, 11, 1553–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crous, P.W. Taxonomy and phylogeny of the genus Mycosphaerella and its anamorphs. Fungal Divers. 2009, 38, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Crous, P.W.; Summerell, B.A.; Mostert, L.; Groenewald, J.Z. Host specificity and speciation of Mycosphaerella and Teratosphaeria species associated with leaf spots of Proteaceae. Persoonia 2008, 20, 59–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spegazzini, C. Fungi argentini additis nonnullis brasiliensibus montevideensibusque. Pugillus quartus (Continuacion). An. Soc. Cient. Argent. 1881, 12, 174–189. [Google Scholar]

- Clements, F.E.; Shear, C.L. The Genera of Fungi; Hafner Publishing Co.: New York, NY, USA, 1931; pp. 1–632. [Google Scholar]

- Samuels, G.J.; Müller, E. Life-history studies of Brazilian Ascomycetes. 7. Rhytidhysteron rufulum and the genus Eutryblidiella. Sydowia 1979, 32, 277–292. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, M.P.; Rawla, G.S. Ascomycetes new to India-III. Nova Hedwigia 1985, 42, 81–90. [Google Scholar]

- Barr, M.E. Some dictyosporous genera and species of Pleosporales in North America. Mem. N. Y. Bot. Gard. 1990, 62, 1–92. [Google Scholar]

- Magnes, M. Weltmonographie der Triblidiaceae. Bibl. Mycol. 1997, 165, 1–177. [Google Scholar]

- Species Fungorum. Available online: http://www.speciesfungorum.org/Names/Names.asp (accessed on 25 February 2021).

- De Silva, N.I.; Tennakoon, D.S.; Thambugala, K.M.; Karunarathna, S.C.; Lumyong, S.; Hyde, K.D. Morphology and multigene phylogeny reveal a new species and a new record of Rhytidhysteron (Dothideomycetes, Ascomycota) from China. AJOM 2020, 3, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, N.T.; Xie, H.M.; Wang, J.H.; Liu, S.B.; Liu, Z.X. First Report on the Molecular Identification of Phytoplasma (16SrI) Associated with Witches’ Broom on Dodonaea viscosa in China. Plant Dis. 2016, 100:6, 1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Locus a | Primers b | PCR: Thermal Cycles: c (Annealing temp. in Bold) | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| act | ACT-512F ACT2Rd | (96 °C: 120 s, 52 °C: 60 s, 72 °C: 90 s) × 40 cycles | [41,42] |

| btub | TUB2Fw TUB4Rd | (94 °C: 30 s, 56 °C: 45 s, 72 °C: 60 s) × 35 cycles | [43] |

| cal | CAL-235F CAL2Rd | (96 °C: 120 s, 50 °C: 60 s, 72 °C: 90 s) × 40 cycles | [42,44] |

| ITS | ITS5 ITS4 | (95 °C: 30 s, 55 °C:50 s, 72 °C: 90 s) × 35 cycles | [45] |

| LSU | LR0R LR5 | (95 °C: 30 s, 55 °C:50 s, 72 °C: 90 s) × 35 cycles | [46,47] |

| rpb2 | fRPB2-5f fRPB2-7cR | (94 °C: 60 s, 58 °C: 60 s, 72 °C: 90 s) × 40 cycles | [48] |

| fRPB2-414R | (96 °C: 120 s, 49 °C: 60 s, 72 °C: 90 s) × 40 cycles | [49] | |

| SSU | NS1 NS4 | (95 °C: 30 s, 55 °C:50 s, 72 °C: 90 s) × 35 cycles | [45] |

| tef1 | EF1-983F EF1-2218R | (95 °C: 30 s, 55 °C:50 s, 72 °C: 90 s) × 35 cycles | [50,51] |

| EF1-728F EF-2 | (96 °C: 120 s, 52 °C: 60 s, 72 °C: 90 s) × 40 cycles | [41,52] |

| Phylum and Class | Order | Family | Species | Country | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ascomycota | |||||

| Dothideomycetes | Botryosphaeriales | Botryosphaeriaceae | Lasiodiplodia iraniensis | Australia | [65] |

| Macrophoma dodonaeae | India | [66] | |||

| Macrophomina phaseolina | Arizona | [67] | |||

| Capnodiales | Capnodiaceae | Antennariella californica | Fiji | [68] | |

| Mycosphaerellaceae | Cercospora dodonaeae | India | [69,70,71] | ||

| Cercospora sp. | Sierra Leone | [72] | |||

| Pseudocercospora dodonaeae | New Zealand | [73,74,75,76,77,78] | |||

| Pseudocercospora mitteriana | China | [79] | |||

| India | [69,71] | ||||

| Pakistan | [71,80] | ||||

| Teratosphaeriaceae | Haniomyces dodonaeae | China | This study | ||

| Hysteriales | Hysteriaceae | Rhytidhysteron hongheense | China | This study | |

| incertae sedis | Pseudoperisporiaceae | Episphaerella dodonaeae | Dominican Republic | [81] | |

| Ecuador | [82] | ||||

| Venezuela | [82] | ||||

| USA | [83] | ||||

| incertae sedis | Mycothyridium pakistanicum | Pakistan | [80] | ||

| Mycothyridium roosselianum | Pakistan | [80] | |||

| Patellariales | Patellariaceae | Tryblidaria pakistani | Pakistan | [80] | |

| Pleosporales | Coniothyriaceae | Coniothyrium sp. | Venezuela | [84] | |

| Corynesporascaceae | Corynespora cassiicola | India | [85] | ||

| Didymosphaeriaceae | Didymosphaeria oblitescens | Pakistan | [80] | ||

| Leptosphaeriaceae | Leptosphaeria dodonaeae | Eritrea | [86] | ||

| Lophiostomataceae | Lophiomurispora hongheensis | China | This study | ||

| Parapyrenochaetaceae | Quixadomyces hongheensis | China | This study | ||

| Pleosporaceae | Pleospora dodonaeae | Cyprus | [87] | ||

| Valsariales | Valsariaceae | Valsaria rubricosa | Pakistan | [80] | |

| Lecanoromycetes | Ostropales | Stictidaceae | Stictis marathwadensis | India | [88,89] |

| Leotiomycetes | Helotiales | Erysiphaceae | Oidium sp. | Iraq | [90] |

| Israel | [90] | ||||

| South Africa | [90] | ||||

| Zimbabwe | [91] | ||||

| Ovulariopsis erysiphoides | Ethiopia | [92] | |||

| Phyllactiniasp. | Ethiopia | [90] | |||

| Sawadaea bicornis | Germany | [93] | |||

| New Zealand | [74,90] | ||||

| South Africa | [90] | ||||

| Takamatsuella circinata | South Africa | [94] | |||

| Sordariomycetes | Diaporthales | Cytosporaceae | Cytospora sp. | USA | [95] |

| Glomerellales | Glomerellaceae | Colletotrichum gloeosporioides | India | [88] | |

| Meliolales | Meliolaceae | Meliola lyoni | Hawaii | [96,97,98,99] | |

| Hypocreales | Nectriaceae | Calonectria cylindrospora | USA | [100,101] | |

| Calonectria pauciramosa | Italy | [102] | |||

| Fusarium solani | Iran | [103] | |||

| Glomerellales | Plectosphaerellaceae | Verticillium dahliae | USA | [95] | |

| New Zealand | [74] | ||||

| Coronophorales | Scortechiniaceae | Tympanopsis lantanae | India | [104] | |

| Amphisphaeriales | Sporocadaceae | Monochaetia dodoneae | Ethiopia | [92] | |

| Pestalotia dodonaeae | Eritrea | [86] | |||

| Sarcostroma kennedyae | New Zealand | [74] | |||

| Seimatosporium kennedyae | New Zealand | [73] | |||

| Togniniales | Togniniaceae | Phaeoacremonium alvesii | Australia | [105,106,107,108] | |

| Phaeoacremonium italicum | Australia | [109] | |||

| Basidiomycota | |||||

| Agaricomycetes | Agaricales | Marasmiaceae | Campanella junghuhnii | Hawaii | [110] |

| Agaricales | incertae sedis | Dendrothele incrustans | New Zealand | [111] | |

| Bartheletiomycetes | Cantharellales | Ceratobasidiaceae | Rhizoctonia sp. | Italy | [112] |

| Hymenochaetales | Hymenochaetaceae | Arambarria cognata | Uruguay | [113] | |

| Fomitiporia australiensis | Australia | [114] | |||

| Phellinus melleoporus | Hawaii | [110] | |||

| Phellinus robustus | USA | [115] | |||

| Phellinus sonorae | USA | [116] | |||

| Schizoporaceae | Hyphodontia alutaria | Hawaii | [110] | ||

| Grandinia breviseta | Hawaii | [110] | |||

| Polyporales | Hyphodermataceae | Hyphoderma sphaeropedunculatum | Hawaii | [110] | |

| Pucciniomycetes | Pucciniales | incertae sedis | Uredo dodonaeae | Indonesia | [117] |

| Oomycota | |||||

| Peronosporomycetes | Peronosporales | Peronosporaceae | Phytophthora drechsleri | Australia | [118,119,120] |

| Phytophthora nicotianae | Italy | [121,122,123] | |||

| Phytophthora palmivora | Italy | [123] | |||

| Pythiaceae | Globisporangium debaryanum | New Zealand | [73,74] | ||

| Globisporangium irregulare | New Zealand | [74] | |||

| Globisporangium ultimum | New Zealand | [73] | |||

| Pythium inflatum | New Zealand | [73,74] | |||

| Pythium sp. | New Zealand | [73] | |||

| USA | [75] |

| Species | Strain | GenBank Accession Numbers | Reference | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSU | LSU | act | cal | ITS | rpb2 | tef1 | btub | |||

| Acidiella bohemica | CBS 132720 | - | KF901984 | - | - | - | KF902178 | - | - | [49] |

| Acidiella parva | CMW 10189 | - | KF901986 | KF903512 | KF902537 | KF901647 | KF902192 | KF903097 * | - | [49] |

| Acrodontium crateriforme | CPC 11509 | - | GU214682 | GU320413 | KX289011 | GU214682 | KX288404 | GU384425 * | - | [124,125] |

| Acrodontium pigmentosum | CBS 111111 | - | KX286963 | - | - | KX287275 | KX288412 | - | - | [125] |

| Alfoldia vorosii | CBS 145501 | MK589346 | MK589354 | - | - | JN859336 | - | MK599320 | - | [126] |

| Alpestrisphaeria jonesii | GZCC 16-0021 | KX687755 | KX687753 | - | - | KX687757 | - | KX687759 | - | [14] |

| Alpestrisphaeria jonesii | GZCC 16-0022 | KX687756 | KX687754 | - | - | KX687758 | - | KX687760 | - | [14] |

| Alpestrisphaeria monodictyoides | V0216 | MH160808 | - | - | MK503662 | - | - | [127] | ||

| Alpestrisphaeria terricola | SC-12H | JX985749 | JX985750 | - | - | JN662930 | - | - | [128] | |

| Amorocoelophoma cassiae | MFLUCC 17-2283 | NG_065775 | NG_066307 | - | - | NR_163330 | MK434894 | MK360041 | - | [127] |

| Angustimassarina acerina | MFLUCC 14-0505 | NG_063573 | KP888637 | - | - | NR_138406 | - | KR075168 | - | [129] |

| Angustimassarina quercicola | MFLUCC 14-0506 | NG_063574 | KP888638 | - | - | KP899133 | - | KR075169 | - | [129] |

| Angustimassarina rosarum | MFLUCC 17-2155 | MT226662 | MT214543 | - | - | MT310590 | MT394678 | MT394726 | - | [130] |

| Apenidiella strumelloidea | CBS 114484 | - | KF937229 | - | - | - | KF937266 | - | - | [49] |

| Araucasphaeria foliorum | CPC 33084 | - | MH327829 | - | - | MH327793 | - | - | - | [131] |

| Astragalicola vasilyevae | MFLUCC 17-0832 | MG829098 | MG828986 | - | - | NR_157504 | MG829248 | MG829193 | - | [130] |

| Austroafricana associata | CPC 13119 | - | KF901824 | KF903526 | KF902528 | KF901507 | KF902177 | KF903087 * | - | [49] |

| Austroafricana sp. | CPC 4313 | - | KF901813 | KF903460 | KF902527 | KF901498 | KF902186 | KF903086 * | - | [49] |

| Austrostigmidium mastodiae | MA 18215 | - | NG_057063 | - | - | - | - | - | - | [132] |

| Austrostigmidium mastodiae | MA 18213 | - | KP282862 | - | - | - | - | - | - | [132] |

| Batcheloromyces alistairii | CPC 12730 | - | KF937220 | - | - | - | KF937252 | - | - | [49] |

| Batcheloromyces leucadendri | CPC 1838 | - | KF937221 | - | - | - | KF937253 | - | - | [49] |

| Batcheloromyces sedgefieldii | CPC 3026 | - | KF937222 | - | - | - | KF937254 | - | - | [49] |

| Biappendiculispora japonica | KT 573 | AB618686 | AB619005 | - | - | LC001728 | - | LC001744 | - | [129,133] |

| Biappendiculispora japonica | KT 686-1 | AB618687 | AB619006 | - | - | LC001729 | - | LC001745 | - | [129,133] |

| Camarosporidiella caraganicola | MFLUCC 17-0726 | MF434300 | MF434212 | - | - | MF434125 | - | MF434388 | - | [134] |

| Camarosporidiella elongata | AFTOL-ID 1568 | DQ678009 | DQ678061 | - | - | - | DQ677957 | DQ677904 | - | [135] |

| Camarosporidiella eufemiana | MFLUCC 17-0207 | MF434321 | MF434233 | - | - | MF434145 | - | MF434408 | - | [134] |

| Camarosporula persooniae | CPC 3350 | - | JF770460 | - | - | - | KF937255 | - | - | [49,136] |

| Capulatispora sagittiformis | KT 1934 | AB618693 | AB369267 | - | - | AB369268 | - | LC001756 | - | [129,133] |

| Catenulostroma hermanusense | CPC 18276 | - | KF902089 | - | - | - | KF902197 | - | - | [49] |

| Catenulostroma protearum | CPC 15370 | - | KF902090 | - | - | - | KF902198 | - | - | [49] |

| Coelodictyosporium pseudodictyosporium | MFLUCC 13-0451 | - | KR025862 | - | - | KR025858 | - | - | - | [137] |

| Coelodictyosporium rosarum | MFLUCC 17-0776 | NG_063674 | NG_059056 | - | - | MG828875 | - | MG829195 | - | [130] |

| Coniothyrium palmarum | CBS 400.71 | EU754054 | JX681084 | - | - | MH860184 | KT389592 | - | KT389792 | [138] |

| Constantinomyces macerans | TRN 440 | - | KF310005 | - | - | NR_164011 | KF310081 | - | - | [139] |

| Constantinomyces minimus | CBS 118766 | - | KF310003 | - | - | NR_144957 | KF310077 | - | - | [139] |

| Crassiclypeus aquaticus | KH 91 | LC312469 | LC312527 | - | - | LC312498 | LC312585 | LC312556 | - | [140] |

| Crassiclypeus aquaticus | KH 104 | LC312470 | LC312528 | - | - | LC312499 | LC312586 | LC312557 | - | [140] |

| Crassiclypeus aquaticus | KH 185 | LC312471 | LC312529 | - | - | LC312500 | LC312587 | LC312558 | - | [140] |

| Crassiclypeus aquaticus | KT 970 | LC312472 | LC312530 | - | - | LC312501 | LC312588 | LC312559 | - | [140] |

| Desertiserpentica hydei | SQUCC 15092 | MW077163 | MW077156 | - | - | MW077147 | MW075773 | MW077163 | - | [54] |

| Devriesia agapanthi | CPC 19833 | - | JX069859 | - | - | - | KJ564346 | - | - | [49,141] |

| Devriesia strelitziae | X1037 | - | GU301810 | - | - | EU436763 | GU371738 | GU349049 * | - | [142] |

| Dimorphiopsis brachystegiae | CPC 22679 | - | KF777213 | - | - | KF777160 | - | - | - | [143] |

| Elasticomyces elasticus | CCFEE 5313 | - | KJ380894 | - | - | FJ415474 | - | - | - | [49,144] |

| Elasticomyces elasticus | CCFEE 5474 | - | KF309991 | - | - | - | KF310046 | - | - | [139] |

| Eupenidiella venezuelensis | CBS 106.75 | - | KF902163 | KF903393 | KF902540 | KF901802 | KF902202 | KF903100 * | - | [49] |

| Euteratosphaeria verrucosiafricana | CPC 11167 | - | - | - | - | DQ303056 | - | - | - | [139] |

| Flabellascoma aquaticum | KUMCC 15-0258 | MN304832 | NG_068307 | - | - | NR_166305 | MN328895 | MN328898 | - | [145] |

| Flabellascoma cycadicola | KT 2034 | LC312473 | LC312531 | - | - | LC312502 | LC312589 | LC312560 | - | [140] |

| Flabellascoma fusiforme | MFLUCC 18-1584 | - | NG_068308 | - | - | NR_166306 | - | MN328902 | - | [105] |

| Flabellascoma minimum | KT 2013 | LC312474 | LC312532 | - | - | LC312503 | LC312590 | LC312561 | - | [140] |

| Flabellascoma minimum | KT 2040 | LC312475 | LC312533 | - | - | LC312504 | LC312591 | LC312562 | - | [140] |

| Forliomyces uniseptata | MFLUCC 15-0765 | NG_061234 | NG_059659 | - | - | NR_154006 | - | KU727897 | - | [146] |

| Friedmanniomyces endolithicus | CCFEE 5199 | - | KF310007 | - | - | - | KF310093 | - | - | [139] |

| Friedmanniomyces endolithicus | CCFEE 5283 | - | KF310006 | - | - | - | KF310053 | - | - | [49] |

| Gloniopsis calami | MFLUCC 15-0739 | NG_063621 | NG_059715 | - | - | NR_164398 | - | KX671965 | - | [147] |

| Gloniopsis calami | MFLUCC 10-0927 | MN577426 | MN577415 | - | - | MN608546 | - | - | - | [148] |

| Gloniopsis praelonga | CBS 112415 | FJ161134 | FJ161173 | - | - | - | FJ161113 | FJ161090 | - | [149] |

| Guttulispora crataegi | MFLUCC 13-0442 | KP899125 | KP888639 | - | - | KP899134 | - | KR075161 | - | [129] |

| Guttulispora crataegi | MFLUCC 14-0993 | KP899126 | KP888640 | - | - | KP899135 | - | KR075162 | - | [129] |

| Haniomyces dodonaeae | KUMCC 20-0220 | MW264221 | MW264191 | MW256802 | MW256805 | MW264212 | MW269527 | MW256813 * | - | This study |

| Haniomyces dodonaeae | KUMCC 20-0221 | MW264222 | MW264192 | MW256803 | MW256806 | MW264213 | MW269528 | MW256814 * | - | This study |

| Hortaea thailandica | CPC 16651 | - | KF902125 | - | - | - | KF902206 | - | - | [49] |

| Hysterium angustatum | MFLUCC 16-0623 | MH535885 | MH535893 | - | - | - | MH535875 | FJ161096 | - | [149,150] |

| Hyweljonesia indica | NFCCI 4146 | - | NG_066398 | - | - | NR_164021 | - | - | - | [151] |

| Hyweljonesia queenslandica | BRIP 61322b | - | NG_059766 | - | - | NR_154095 | - | - | - | [152] |

| Incertomyces perditus | CCFEE 5385 | - | KF310008 | - | - | KF309977 | KF310083 | - | - | [139] |

| Incertomyces vagans | CCFEE 5393 | - | KF310009 | - | - | NR_154064 | KF310057 | - | - | [139] |

| Lapidomyces hispanicus | TRN126 | - | KF310016 | - | - | - | KF310076 | - | - | [139] |

| Lentistoma bipolare | HKUCC 10069 | LC312476 | LC312534 | - | - | LC312505 | LC312592 | LC312563 | - | [140] |

| Lentistoma bipolare | HKUCC 10110 | LC312477 | LC312535 | - | - | LC312506 | LC312593 | LC312564 | - | [140] |

| Lentistoma bipolare | HKUCC 8277 | LC312478 | LC312536 | - | - | LC312507 | LC312594 | LC312565 | - | [140] |

| Lentistoma bipolare | KT 2415 | LC312483 | LC312541 | - | - | LC312512 | LC312599 | LC312570 | - | [140] |

| Lentistoma bipolare | KT 3056 | LC312484 | LC312542 | - | - | LC312513 | LC312600 | LC312571 | - | [140] |

| Leptoparies palmarum | KT 1653 | LC312485 | LC312543 | - | - | LC312514 | LC312601 | LC312572 | - | [140] |

| Leptosphaeria conoidea | CBS 616.75 | JF740099 | JF740279 | - | - | JF740201 | KT389639 | - | KT389804 | [153] |

| Leptosphaeria doliolum | CBS 505.75 | NG_062778 | NG_068574 | - | - | NR_155309 | KY064035 | GU349069 | JF740144 | [154] |

| Lophiohelichrysum helichrysi | MFLUCC 15-0701 | KT333437 | KT333436 | - | - | KT333435 | - | KT427535 | - | [155] |

| Lophiopoacea paramacrostoma | MFLUCC 11-0463 | KP899122 | KP888636 | - | - | - | - | - | - | [129] |

| Lophiomurispora hongheensis | KUMCC 20-0217 | MW264225 | MW264195 | - | - | MW264216 | MW256808 | MW256817 | - | This study |

| Lophiomurispora hongheensis | KUMCC 20-0223 | MW264226 | MW264196 | - | - | MW264217 | MW256809 | MW256818 | - | This study |

| Lophiomurispora hongheensis | KUMCC 20-0216 | MW264227 | MW264197 | - | - | MW264218 | MW256810 | MW256819 | - | This study |

| Lophiomurispora hongheensis | KUMCC 20-0219 | MW264228 | MW264198 | - | - | MW264219 | MW256811 | MW256820 | - | This study |

| Lophiomurispora hongheensis | KUMCC 20-0224 | MW264229 | MW264199 | - | - | MW264220 | MW256812 | MW256821 | - | This study |

| Lophiopoacea winteri | KT 740 | AB618699 | AB619017 | - | - | JN942969 | JN993487 | LC001763 | - | [129,133,156] |

| Lophiopoacea winteri | KT 764 | AB618700 | AB619018 | - | - | JN942968 | JN993488 | LC001764 | - | [129,133,156] |

| Lophiostoma caulium | CBS 623.86 | GU296163 | GU301833 | - | - | - | GU371791 | - | - | [152] |

| Lophiostoma macrostomum | KT 635 | AB521731 | AB433273 | - | - | AB433275 | JN993484 | LC001752 | - | [129,133] |

| Lophiostoma multiseptatum | JCM 17668 | AB618684 | AB619003 | - | - | LC001726 | - | LC001742 | - | [129,133] |

| Lophiostoma multiseptatum | MAFF 239451 | AB618685 | AB619004 | - | - | LC001727 | - | LC001743 | - | [129,133] |

| Lophiostoma rosae | TASM 6115 | NG_065145 | NG_069558 | - | - | NR_158531 | - | MG829205 | - | [130] |

| Lophiostoma semiliberum | KT 828 | AB618696 | AB619014 | - | - | JN942970 | JN993489 | LC001759 | - | [129,133,156] |

| Massarina cisti | CBS 266.62 | AB797249 | AB807539 | - | - | LC014568 | FJ795464 | AB808514 | - | [157,158] |

| Massarina eburnea | CBS 473.64 | GU296170 | GU301840 | - | - | AF383959 | GU371732 | GU349040 | - | [143,159] |

| Meristemomyces frigidum | CCFEE 5457 | - | GU250389 | - | - | - | KF310066 | - | - | [49,144] |

| Meristemomyces frigidum | CCFEE 5507 | - | KF310013 | - | - | - | KF310067 | - | - | [139] |

| Monticola elongata | CCFEE 5492 | - | KF309994 | - | - | - | KF310065 | - | - | [139] |

| Myrtapenidiella corymbia | CPC 14640 | - | KF901838 | KF903558 | KF902558 | KF901517 | KF902227 | KF903119 * | - | [49] |

| Neocatenulostroma abietis | CBS 110038 | - | KF937226 | - | - | - | KF937263 | - | - | [49] |

| Neocatenulostroma microsporum | CPC 1960 | - | KF901814 | - | KF902561 | KF901499 | KF902232 | KF903122 * | - | [49] |

| Neocucurbitaria ribicola | CBS 142394 | MF795840 | MF795785 | - | - | MF795785 | MF795827 | MF795873 | MF795911 | [160] |

| Neoleptosphaeria jonesii | MFLUCC 16-1442 | NG_063625 | KY211870 | - | - | NR_152375 | - | KY211872 | - | [161] |

| Neopaucispora rosaecae | MFLUCC 17-0807 | NG_061293 | NG_059869 | - | - | MG828924 | - | MG829217 | - | [130] |

| Neophaeosphaeria agaves | CBS 136429 | - | KF777227 | - | - | NR_137833 | - | - | - | [143] |

| Neophaeosphaeria filamentosa | CBS 102202 | GQ387516 | GQ387577 | - | - | JF740259 | GU371773 | - | - | [162] |

| Neophaeosphaeria phragmiticola | KUMCC 16-0216 | MG837008 | MG837009 | - | - | - | - | MG838020 | - | [163] |

| Neophaeothecoidea proteae | CPC 2831 | - | KF937228 | - | - | - | KF937265 | - | - | [49] |

| Neopyrenochaeta acicola | CBS 812.95 | NG_065567 | GQ387602 | - | - | NR_160055 | LT623271 | - | LT623232 | [164] |

| Neopyrenochaeta cercidis | MFLU 18-2089 | NG_065769 | MK347932 | - | - | MK347718 | MK434908 | - | - | [127] |

| Neopyrenochaeta fragariae | CBS 101634 | GQ387542 | GQ387603 | - | - | LT623217 | LT623270 | - | LT623231 | [164] |

| Neopyrenochaeta inflorescentiae | CBS 119222 | - | EU552153 | - | - | EU552153 | LT623272 | - | LT623233 | [165] |

| Neopyrenochaeta maesuayensis | MFLUCC 14-0043 | - | MT183504 | - | - | NR_170043 | - | MT454042 | - | [166] |

| Neopyrenochaeta telephoni | CBS 139022 | - | NG_067485 | - | - | KM516291 | LT717685 | - | LT717678 | [154] |

| Neotrematosphaeria biappendiculata | KT 1124 | GU205256 | GU205227 | - | - | - | - | - | - | [129] |

| Neotrematosphaeria biappendiculata | KT 975 | GU205254 | GU205228 | - | - | - | - | - | - | [129] |

| Neotrimmatostroma excentricum | CPC 13092 | - | KF901840 | KF903534 | KF902562 | KF901518 | KF902236 | KF903123 * | - | [49] |

| Neovaginatispora clematidis | MFLUCC 17-2149 | MT226676 | MT214559 | - | - | MT310606 | - | MT394738 | - | [167] |

| Neovaginatispora fuckelii | CBS 101952 | FJ795496 | DQ399531 | - | - | - | FJ795472 | - | - | [158] |

| Neovaginatispora fuckelii | KH 161 | AB618689 | AB619008 | - | - | LC001731 | - | LC001749 | - | [129,133] |

| Neovaginatispora fuckelii | KT 634 | AB618690 | AB619009 | - | - | LC001732 | - | LC001750 | - | [129,133] |

| Oleoguttula mirabilis | CCFEE 5522 | - | KF310019 | - | - | - | KF310070 | - | - | [139] |

| Parapaucispora pseudoarmatispora | KT 2237 | LC100018 | LC100026 | - | - | LC100021 | - | LC100030 | - | [168] |

| Parapenidiella pseudo tasmaniensis | CPC 12400 | - | KF901844 | KF903562 | KF902589 | KF901522 | KF902265 | KF903152 * | - | [49] |

| Parapenidiella tasmaniensis | CPC 1555 | - | KF901843 | KF903451 | KF902587 | KF901521 | KF902263 | KF903150 * | - | [49] |

| Parapyrenochaeta acaciae | CPC 25527 | - | KX228316 | - | - | NR_155674 | LT717686 | - | LT717679 | [53] |

| Parapyrenochaeta protearum | CBS 131315 | - | JQ044453 | - | - | JQ044434 | LT717683 | - | LT717677 | [53] |

| Paucispora kunmingense | MFLUCC 17-0932 | MF173430 | NG_059829 | - | - | NR_156625 | MF173436 | MF173434 | - | [169] |

| Paucispora quadrispora | KH 448 | LC001720 | LC001722 | - | - | LC001733 | - | LC001754 | - | [129] |

| Paucispora quadrispora | KT 843 | AB618692 | AB619011 | - | - | LC001734 | - | LC001755 | - | [129,133] |

| Paucispora versicolor | KH 110 | LC001721 | AB918732 | - | - | AB918731 | - | LC001760 | - | [129,133] |

| Penidiella columbiana | CBS 486.80 | - | KF901965 | KF903587 | KF902594 | KF901630 | KF902272 | KF903158 * | - | [49] |

| Penidiellomyces aggregatus | CBS 128772 | - | NG_057905 | - | - | NR_137772 | - | - | - | [170] |

| Penidiellomyces drakensbergensis | CPC 19778 | - | NG_059482 | - | - | NR_111821 | - | - | - | [141] |

| Penidiellopsis radicularis | CBS 131976 | - | KU216314 | - | KU216292 | KT833148 | - | KU216339 * | - | [171] |

| Penidiellopsis ramosus | CBMAI 1937 | - | KU216317 | - | KU216295 | KT833151 | - | KU216342 * | - | [171] |

| Phaeoseptumcarolshearerianum | NFCCI-4221 | MK307816 | MK307813 | - | - | MK307810 | MK309877 | MK309874 | - | [172] |

| Phaeoseptum hydei | MFLUCC 17-0801 | MT240624 | MT240623 | - | - | MT240622 | - | MT241506 | - | [40] |

| Phaeoseptum manglicola | NFCCI-4666 | MK307817 | MK307814 | - | - | MK307811 | MK309878 | MK309875 | - | [172] |

| Phaeoseptum terricola | MFLUCC 10-0102 | MH105780 | MH105779 | - | - | MH105778 | MH105782 | MH105781 | - | [163] |

| Phaeothecoidea Intermedia | CPC 13711 | - | KF902106 | KF903564 | KF902606 | KF901752 | KF902286 | KF903171 * | - | [49] |

| Phaeothecoidea Minutispora | CPC 13710 | - | KF902108 | KF903659 | KF902607 | KF901753 | KF902288 | KF903172 * | - | [49] |

| Piedraia hortae var. hortae | CBS 480.64 | - | KF901943 | - | - | - | KF902289 | - | - | [49] |

| Piedraia hortae var. paraguayensis | CBS 276.32 | - | KF901816 | - | - | - | - | - | - | [49] |

| Piedraia quintanilhae | CBS 327.63 | - | KF901957 | - | - | - | - | - | - | [49] |

| Platystomum actinidiae | KT 521 | JN941375 | JN941380 | - | - | JN942963 | JN993490 | LC001747 | - | [129,156] |

| Platystomum crataegi | MFLUCC 14-0925 | KT026113 | KT026109 | - | - | KT026117 | - | KT026121 | - | [129] |

| Platystomum rosae | MFLU 15-2569 | KY264750 | KY264746 | - | - | KY264742 | - | - | - | [173] |

| Platystomum rosae | MFLUCC 15-0633 | KT026115 | KT026111 | - | - | KT026119 | - | - | - | [129] |

| Platystomum salicicola | MFLUCC 15-0632 | KT026114 | KT026110 | - | - | KT026118 | - | - | - | [129] |

| Pseudolophiostoma cornisporum | KH 322 | LC312486 | LC312544 | - | - | LC312515 | LC312602 | LC312573 | - | [140] |

| Pseudolophiostoma obtusisporum | KT 2838 | LC312489 | LC312547 | - | - | LC312518 | LC312605 | LC312576 | - | [140] |

| Pseudolophiostoma obtusisporum | KT 3119 | LC312491 | LC312549 | - | - | LC312520 | LC312607 | LC312578 | - | [140] |

| Pseudolophiostoma tropicum | KH 352 | LC312492 | LC312550 | - | - | LC312521 | LC312608 | LC312579 | - | [140] |

| Pseudolophiostoma tropicum | KT 3134 | LC312493 | LC312551 | - | - | LC312522 | LC312609 | LC312580 | - | [140] |

| Pseudopaucispora brunneospora | KH 227 | LC312494 | LC312552 | - | - | LC312523 | LC312610 | LC312581 | - | [140] |

| Pseudoplatystomum scabridisporum | BCC 22835 | GQ925831 | GQ925844 | - | - | - | GU479830 | GU479857 | - | [174] |

| Pseudoplatystomum scabridisporum | BCC 22836 | GQ925832 | GQ925845 | - | - | - | GU479829 | GU479856 | - | [174] |

| Pseudopyrenochaeta lycopersici | CBS 306.65 | NG_062728 | MH870217 | - | - | NR_103581 | LT717680 | - | LT717674 | [154] |

| Pseudopyrenochaeta terrestris | CBS 282.72 | - | LT623216 | - | - | LT623228 | LT623287 | - | LT623246 | [53] |

| Pseudoteratosphaeria flexuosa | CPC 673 | - | KF902098 | KF903403 | KF902653 | KF901745 | KF902345 | KF903228 * | - | [49] |

| Pseudoteratosphaeria flexuosa | CPC 1109 | - | KF902110 | KF903421 | KF902654 | KF901755 | KF902346 | - | - | [49] |

| Pyrenochaeta nobilis | CBS 407.76 | DQ898287 | EU754206 | - | - | NR_103598 | DQ677991 | DQ677936 | MF795916 | [162] |

| Pyrenochaeta pinicola | CBS 137997 | - | KJ869209 | - | - | KJ869152 | LT717684 | - | KJ869249 | [175] |

| Pyrenochaeta sp. | DTO 305-C6 | - | KX171361 | - | - | KX147606 | - | - | - | [176] |

| Pyrenochaetopsis botulispora | CBS 142458 | - | LN907440 | - | - | LT592945 | LT593084 | - | LT593014 | [53] |

| Pyrenochaetopsis globosa | CBS 143034 | - | LN907418 | - | - | LT592934 | LT593072 | - | LT593003 | [53] |

| Pyrenochaetopsis paucisetosa | CBS 142460 | - | LN907336 | - | - | LT592897 | LT593035 | - | LT592966 | [53] |

| Pyrenochaetopsis setosissima | CBS 119739 | - | GQ387632 | - | - | LT623227 | LT623285 | - | LT623245 | [162] |

| Queenslandipenidiella kurandae | CPC 13333 | - | KF901860 | KF903538 | KF902663 | KF901538 | KF902356 | KF903238 * | - | [49] |

| Quixadomyces cearensis | HUEFS 238438 | - | NG_066409 | - | - | NR_160606 | - | - | - | [131] |

| Quixadomyces hongheensis | KUMCC 20-0215 | MW264223 | MW264193 | - | - | MW264214 | MW269529 | MW256815 | MW256804 | This study |

| Quixadomyces hongheensis | HKAS112346 | MW541833 | MW541822 | - | - | MW541826 | MW556136 | MW556134- | MW556137 | This study |

| Quixadomyces hongheensis | HKAS112347 | MW541834 | MW541823 | - | - | MW541827 | - | MW556135- | MW556138 | This study |

| Ramusculicola clematidis | MFLUCC 17-2146 | NG_070667 | MT214596 | - | - | MT310640 | MT394707 | MT394652 | - | [167] |

| Readeriella angustia | CPC 13608 | - | KF902114 | KF903566 | KF902669 | KF901759 | KF902364 | KF903246 * | - | [49] |

| Readeriella deanei | CPC 12715 | - | KF901864 | KF903583 | KF902673 | KF901542 | KF902368 | KF903250 * | - | [49] |

| Readeriella dimorphospora | CPC 12636 | - | KF901866 | KF903622 | KF902675 | KF901544 | KF902370 | KF903252 * | - | [49] |

| Readeriella menaiensis | CPC 14447 | - | KF901870 | KF903572 | KF902678 | KF901548 | KF902374 | KF903256 * | - | [49] |

| Recurvomyces mirabilis | CCFEE 5264 | - | GU250372 | - | - | - | KF310059 | - | - | [139,144] |

| Recurvomyces mirabilis | CCFEE 5475 | - | KC315876 | - | - | - | KF310060 | - | - | [139,144] |

| Rhytidhysteron bruguierae | MFLUCC 17-1502 | MN632464 | MN632453 | - | - | MN632458 | - | MN635662 | - | [55] |

| Rhytidhysteron bruguierae | MFLUCC 17-1515 | MN632463 | MN632452 | - | - | MN632457 | - | MN635661 | - | [55] |

| Rhytidhysteron bruguierae | MFLUCC 18-0398 | MN017901 | MN017833 | - | - | - | - | MN077056 | - | [172] |

| Rhytidhysteron bruguierae | MFLUCC 17-1511 | MN632465 | MN632454 | - | - | MN632459 | - | - | - | [55] |

| Rhytidhysteron camporesii | HKAS 104277 | MN429072 | - | - | MN429069 | - | MN442087 | - | [148] | |

| Rhytidhysteron chromolaenae | MFLUCC 17-1516 | NG_070139 | NG_068675 | - | - | MN632461 | - | MN635663 | - | [55] |

| Rhytidhysteron erioi | MFLU 16-0584 | - | MN429071 | - | - | MN429068 | - | MN442086 | - | [148] |

| Rhytidhysteron hongheense | KUMCC 20-0222 | MW264224 | MW264194 | - | - | MW264215 | MW256807 | MW256816 | - | This study |

| Rhytidhysteron hongheense | HKAS112348 | MW541831 | MW541820 | - | - | MW541824 | - | MW556132 | - | This study |

| Rhytidhysteron hongheense | HKAS112349 | MW541832 | MW541821 | - | - | MW541825 | - | MW556133 | - | This study |

| Rhytidhysteron hysterinum | EB 0351 | - | GU397350 | - | - | - | - | GU397340 | - | [149] |

| Rhytidhysteron hysterinum | CBS 316.71 | - | MH871912 | - | - | MH860141 | - | - | - | [154] |

| Rhytidhysteron magnoliae | MFLUCC 18-0719 | MN989382 | MN989384 | - | - | MN989383 | - | MN997309 | - | [177] |

| Rhytidhysteron mangrovei | MFLUCC 18-1113 | - | NG_067868 | - | - | NR_165548 | - | MK450030 | - | [178] |

| Rhytidhysteron neorufulum | MFLUCC 13-0216 | KU377571 | KU377566 | - | - | KU377561 | - | KU510400 | - | [177] |

| Rhytidhysteron neorufulum | GKM 361A | GU296192 | GQ221893 | - | - | - | - | - | - | [179] |

| Rhytidhysteron neorufulum | HUEFS 192194 | - | KF914915 | - | - | - | - | - | - | [180] |

| Rhytidhysteron neorufulum | MFLUCC 12-0528 | KJ418119 | KJ418117 | - | - | KJ418118 | - | - | - | [181] |

| Rhytidhysteron neorufulum | CBS 306.38 | AF164375 | FJ469672 | - | - | - | - | GU349031 | - | [142] |

| Rhytidhysteron neorufulum | MFLUCC 12-0011 | KJ418110 | KJ418109 | - | - | KJ206287 | - | - | - | [181] |

| Rhytidhysteron neorufulum | MFLUCC 12-0567 | KJ546129 | KJ526126 | - | - | KJ546124 | - | - | - | [181] |

| Rhytidhysteron neorufulum | MFLUCC 12-0569 | KJ546131 | KJ526128 | - | - | KJ546126 | - | - | - | [181] |

| Rhytidhysteron neorufulum | MFLUCC 14-0577 | KU377570 | KU377565 | - | - | KU377560 | - | KU510399 | - | [177] |

| Rhytidhysteron opuntiae | GKM 1190 | GQ221892 | - | - | - | - | GU397341 | - | [179] | |

| Rhytidhysteron rufulum | EB 0384 | GU397368 | GU397354 | - | - | - | - | - | - | [182] |

| Rhytidhysteron rufulum | EB 0382 | GU397367 | GU397352 | - | - | - | - | - | - | [182] |

| Rhytidhysteron rufulum | EB 0383 | GU397353 | - | - | - | - | - | - | [182] | |

| Rhytidhysteron rufulum | MFLUCC 12-0013 | KJ418113 | KJ418111 | - | - | KJ418112 | - | - | - | [181] |

| Rhytidhysteron tectonae | MFLUCC 13-0710 | KU712457 | KU764698 | - | - | KU144936 | - | KU872760 | - | [183] |

| Rhytidhysteron thailandicum | MFLUCC 13-0051 | MN509434 | - | - | MN509433 | - | MN509435 | - | [56] | |

| Rhytidhysteron thailandicum | MFLUCC 12-0530 | KJ546128 | KJ526125 | - | - | KJ546123 | - | - | - | [172] |

| Rhytidhysteron thailandicum | MFLUCC 14-0503 | KU377569 | KU377564 | - | - | KU377559 | - | KU497490 | - | [177] |

| Seltsamia ulmi | CBS 143002 | MF795794 | MF795794 | - | - | MF795794 | MF795836 | MF795882 | MF795918 | [160] |

| Sigarispora arundinis | KT 651 | AB618680 | AB618999 | - | - | JN942965 | JN993486 | LC001738 | - | [129,133] |

| Sigarispora caudata | MAFF 239453 | AB618681 | AB619000 | - | - | LC001723 | - | LC001739 | - | [129,133] |

| Sigarispora caulium | MAFF 239450 | AB618682 | AB619001 | - | - | LC001724 | - | LC001740 | - | [129,133] |

| Sigarispora caulium | JCM 17669 | AB618683 | AB619002 | - | - | LC001725 | - | LC001741 | - | [129,133] |

| Sigarispora ononidis | MFLUCC 15-2667 | KU243126 | KU243125 | - | - | KU243128 | - | KU243127 | - | [169] |

| Sigarispora rosicola | MFLU 15-1888 | NG_062116 | MG829080 | - | - | MG828968 | - | MG829240 | - | [130] |

| Simplicidiella nigra | CBMAI 1939 | - | KU216313 | - | KU216291 | KT833147 | - | KU216338 * | - | [171] |

| Sparticola junci | MFLUCC 15-0030 | NG_061235 | KU721765 | - | - | NR_154428 | KU727900 | KU727898 | - | [146] |

| Staninwardia suttonii | CPC 13055 | - | KF901874 | KF903517 | KF902693 | KF901552 | KF902392 | KF903270 * | - | [49] |

| Staurosphaeria lycii | MFLUCC 17-0210 | MF434372 | MF434284 | - | - | MF434196 | - | MF434458 | - | [134] |

| Staurosphaeria lycii | MFLUCC 17-0211 | MF434373 | MF434285 | - | - | MF434197 | - | MF434459 | - | [134] |

| Stenella araguata | FMC 245 | - | KF902168 | - | - | - | KF902393 | - | - | [49] |

| Suberoteratosphaeria pseudosuberosa | CPC 12085 | - | KF902144 | KF903508 | - | KF901786 | - | KF903275 * | - | [49] |

| Suberoteratosphaeria xenosuberosa | CPC 13093 | - | KF901879 | KF903584 | - | KF901557 | KF902402 | KF903280 * | - | [49] |

| Teichospora mariae | C136 | - | KU601581 | - | - | KU601581 | KU601595 | KU601611 | - | [184] |

| Teichospora rubriostiolata | TR 7 | - | KU601590 | - | - | KU601590 | KU601599 | KU601609 | - | [184] |

| Teichospora thailandica | MFLUCC 17-2093 | MT226708 | MT214597 | - | - | MT310641 | MT394708 | MT394653 | - | [167] |

| Teichospora trabicola | C 134 | - | KU601591 | - | - | KU601591 | KU601600 | KU601601 | - | [184] |

| Teratoramularia infinita | CBS 141104 | - | KX287249 | KX287828 | KX289125 | KX287545 | KX288710 | KX288107 * | - | [125] |

| Teratoramularia rumicicola | CBS 141106 | - | KX287255 | - | - | KX287550 | KX288716 | KX288113 * | - | [125] |

| Teratosphaeria aurantia | MUCC 668 | - | KF901884 | KF903578 | KF902700 | KF901561 | KF902409 | KF903284 * | - | [49] |

| Teratosphaeria blakelyi | CPC 12837 | - | KF901888 | KF903518 | KF902704 | KF901565 | KF902413 | KF903288 * | - | [49] |

| Teratosphaeria destructans | CPC 1368 | - | KF901898 | KF903447 | KF902716 | KF901574 | KF902427 | KF903301 * | - | [49] |

| Teratosphaeria fimbriata | CPC 13324 | - | KF901901 | KF903529 | KF902720 | KF901577 | KF902430 | KF903306 * | - | [49] |

| Teratosphaeria gauchensis | CMW 17331 | - | KF902148 | KF903521 | KF902729 | KF901790 | KF902439 | KF903315 * | - | [49] |

| Teratosphaeria mareebensis | CPC 17272 | - | KF901906 | KF903581 | KF902734 | KF901582 | KF902444 | KF903320 * | - | [49] |

| Teratosphaeria pseudocryptica | CPC 11267 | - | KF902032 | KF903598 | KF902760 | KF901687 | KF902472 | KF903348 * | - | [49] |

| Teratosphaeriaceae sp. | CPC 13680 | - | KF901921 | KF903657 | KF902765 | KF901597 | KF902477 | KF903353 * | - | [49] |

| Teratosphaeriaceae sp. | CCFEE 5569 | - | KF310015 | - | - | - | KF310071 | - | - | [139] |

| Teratosphaericola pseudoafricana | CPC 1231 | - | KF902045 | KF903435 | KF902782 | KF901699 | KF902499 | KF903370 * | - | [49] |

| Teratosphaericola pseudoafricana | CPC 1230 | - | KF902084 | KF903473 | KF902783 | KF901737 | KF902500 | KF903371 * | - | [49] |

| Teratosphaeriopsis pseudoafricana | CPC 1261 | - | KF902085 | KF903436 | KF902784 | KF901738 | KF902501 | KF903372 * | - | [49] |