Morphology and Comparative Transcriptome Analysis of Resistant and Susceptible Bitter Gourd (Momordica charantia L.) Reveals the Molecular Response Related to Powdery Mildew Resistance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Identification and Phylogenetic Analysis of PM Pathogen

2.2. Plant Materials and Treatment

2.3. Scanning Electron Microscope

2.4. RNA-Seq Analysis

2.5. Analysis of the MLO Gene

2.6. qRT-PCR Analysis

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Identification of PM Pathogen in Bitter Gourd Leaves

3.2. Phenotypic Changes and Microscopic Observation in Bitter Gourd Leaves After P. xanthii Infection

3.3. Transcriptomic Data Analysis of Bitter Gourd Leaves After P. xanthii Infection

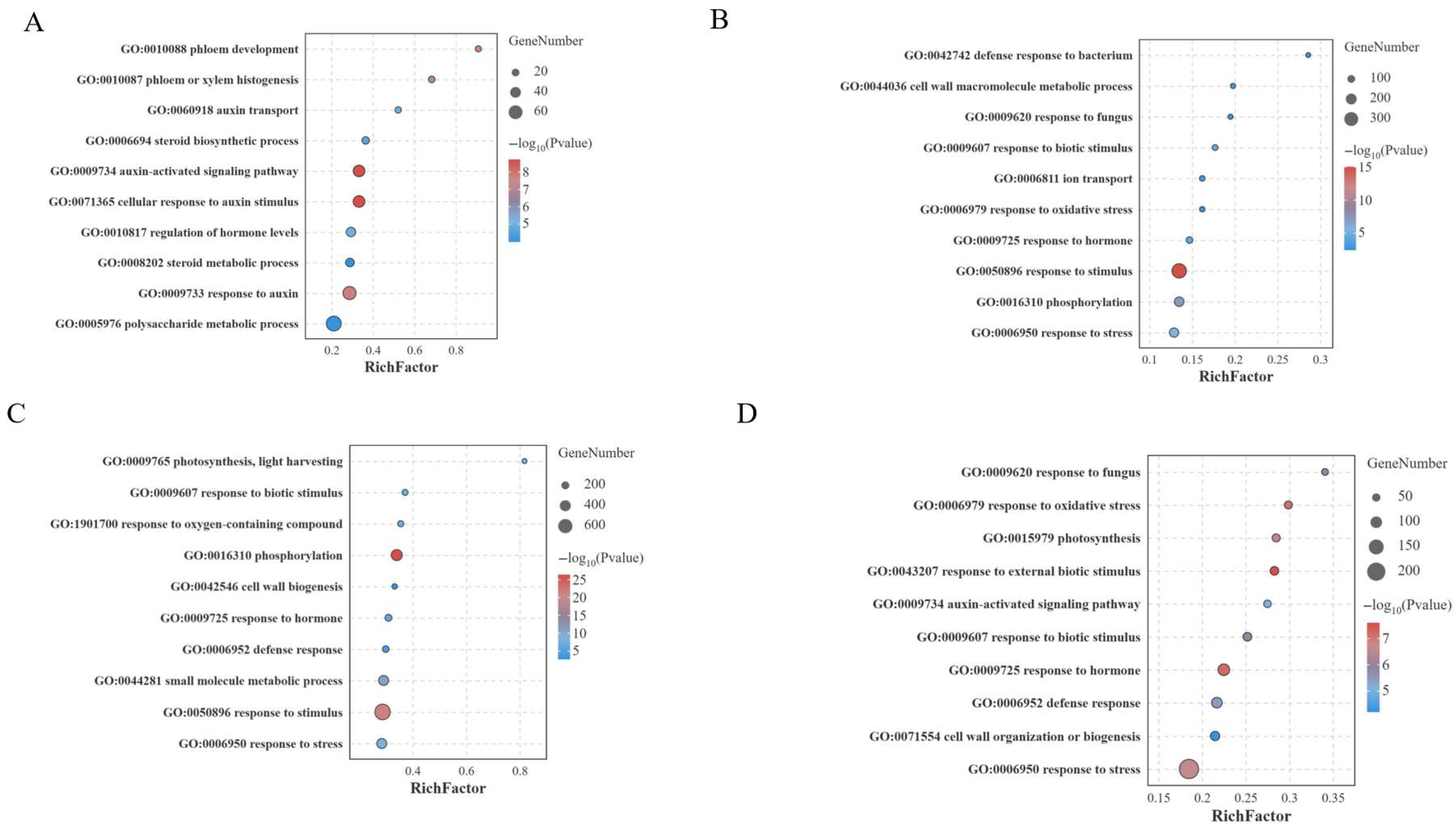

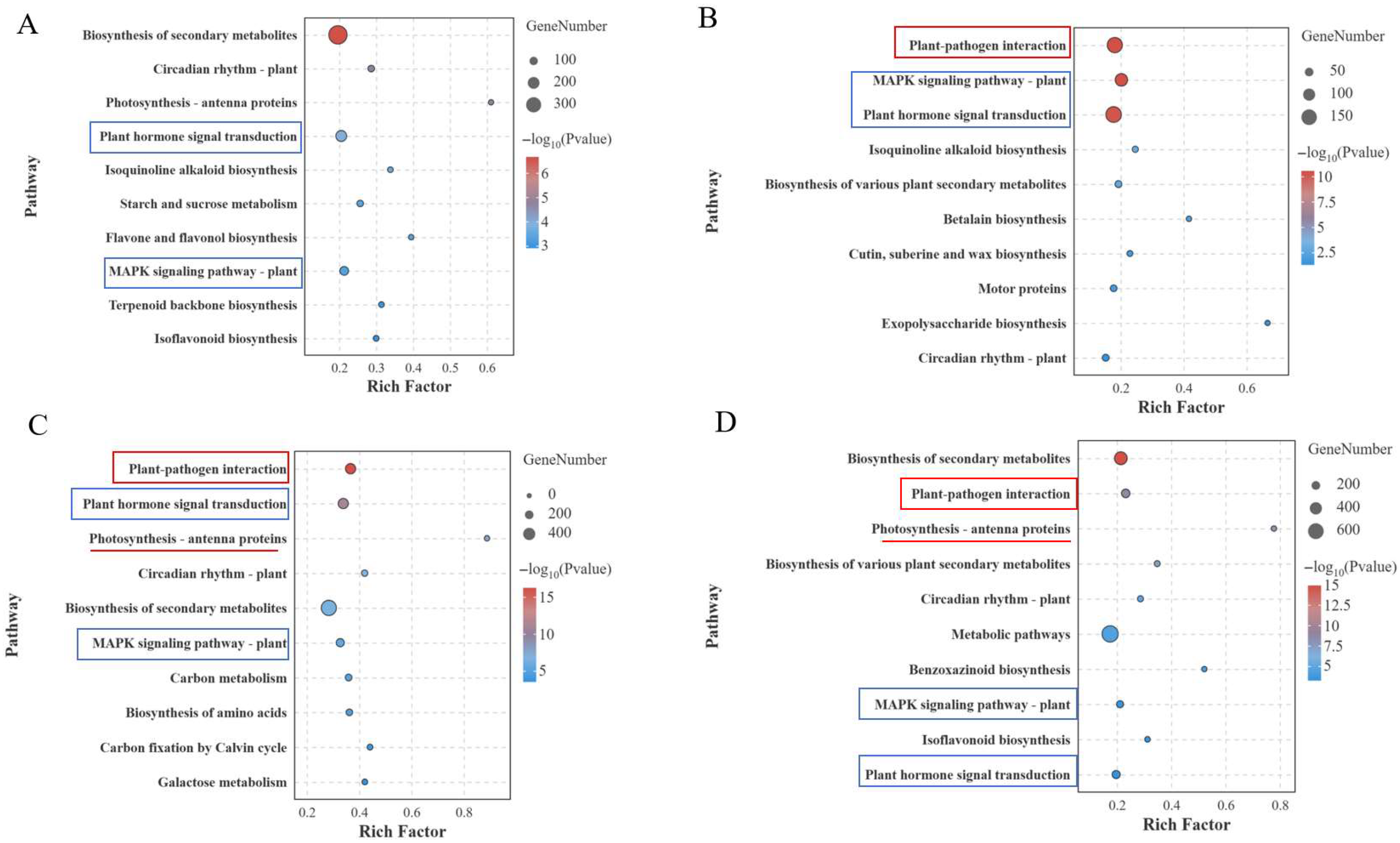

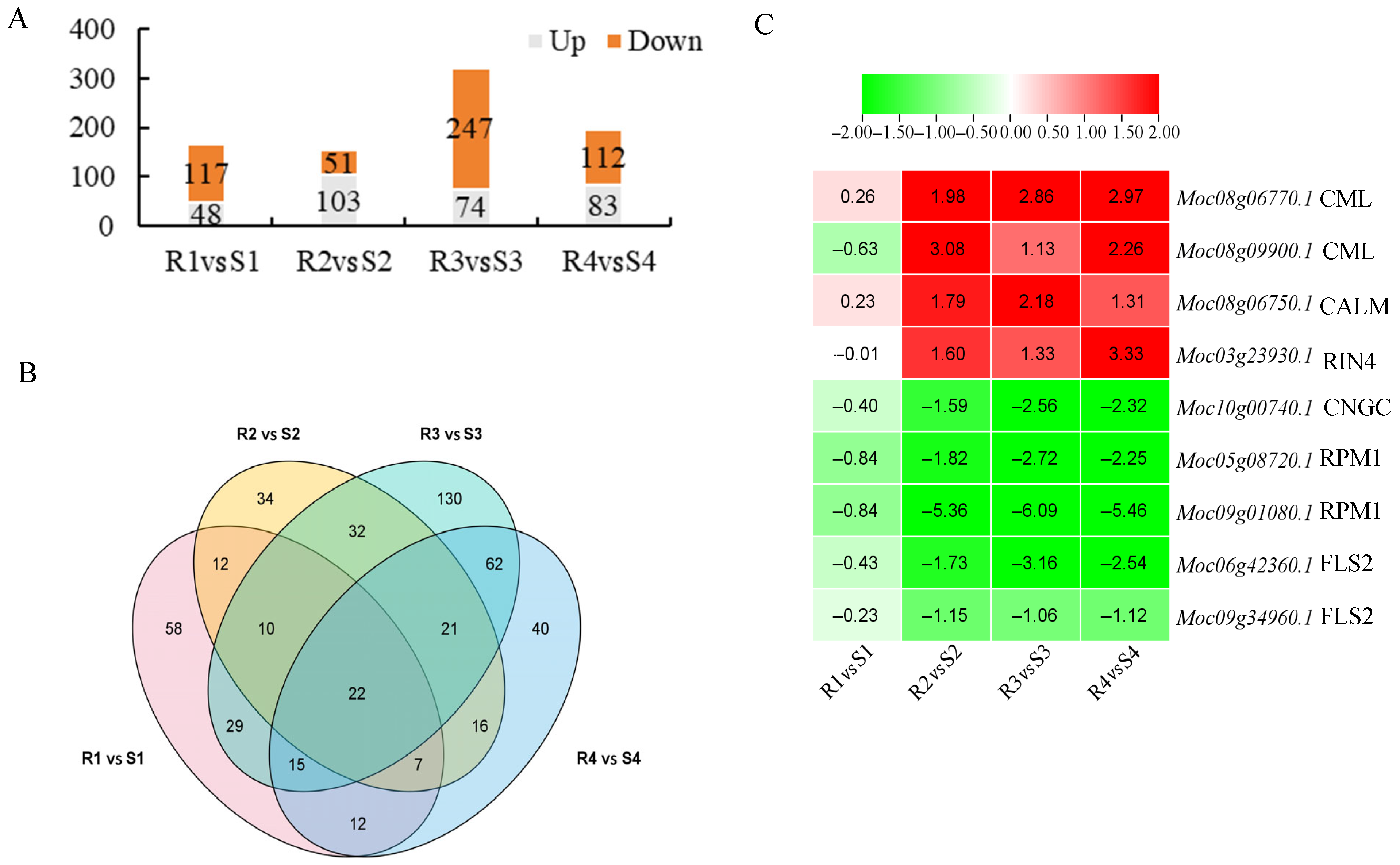

3.4. GO and KEGG Enrichment Analysis of DEGs

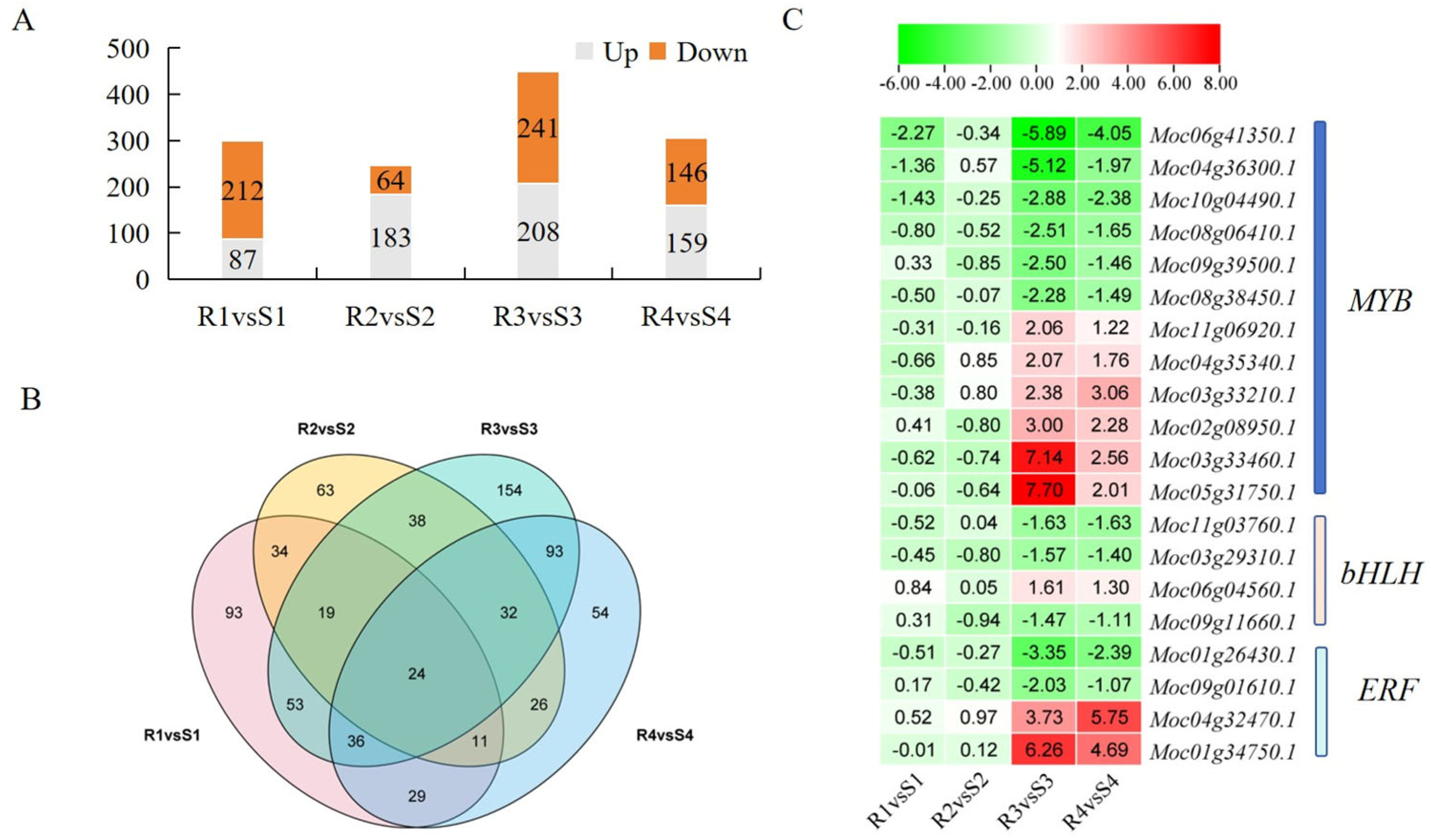

3.5. TF Analysis Involved in Regulation of PM Resistance

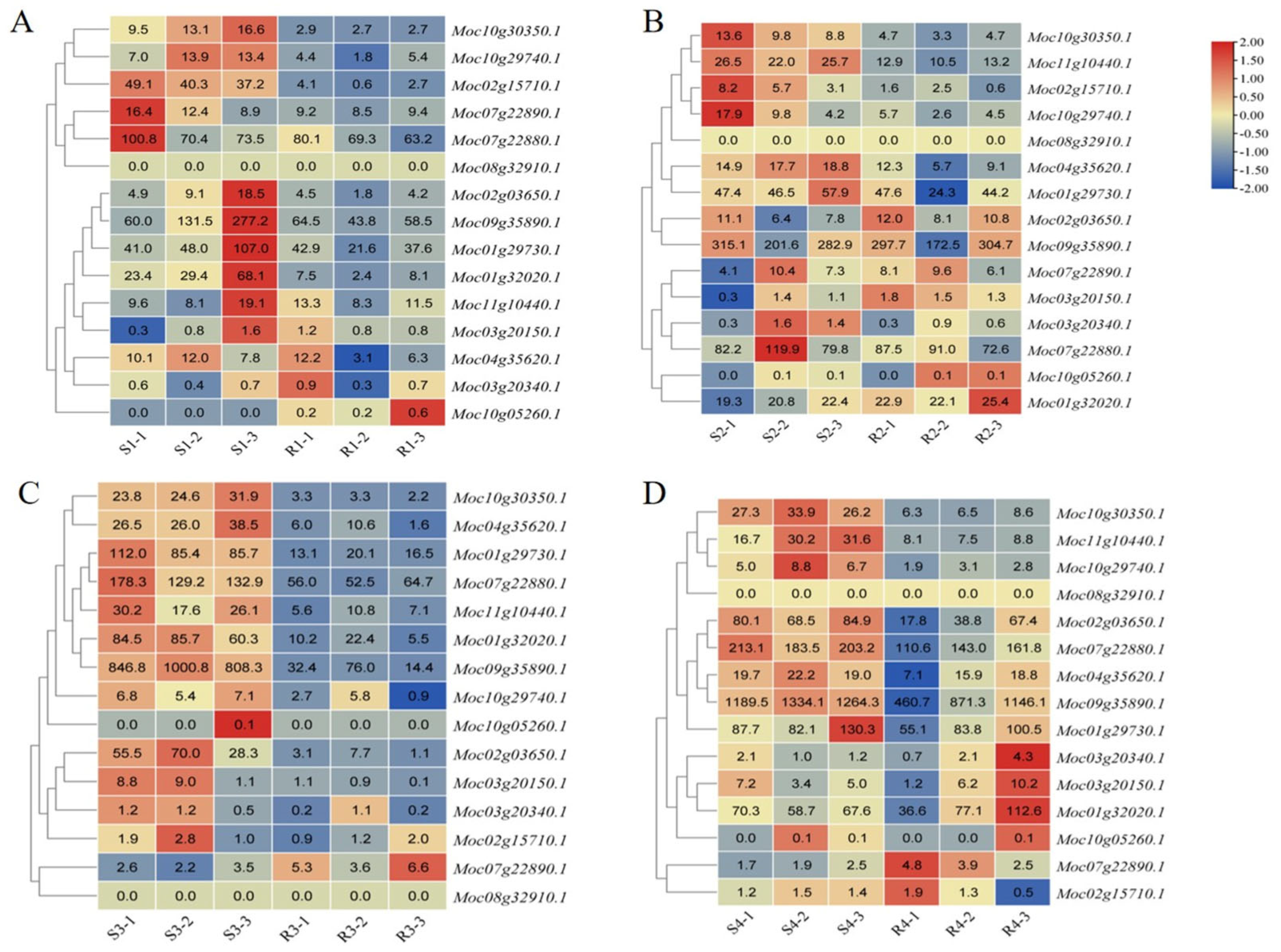

3.6. MLO Genes Related to PM Resistance

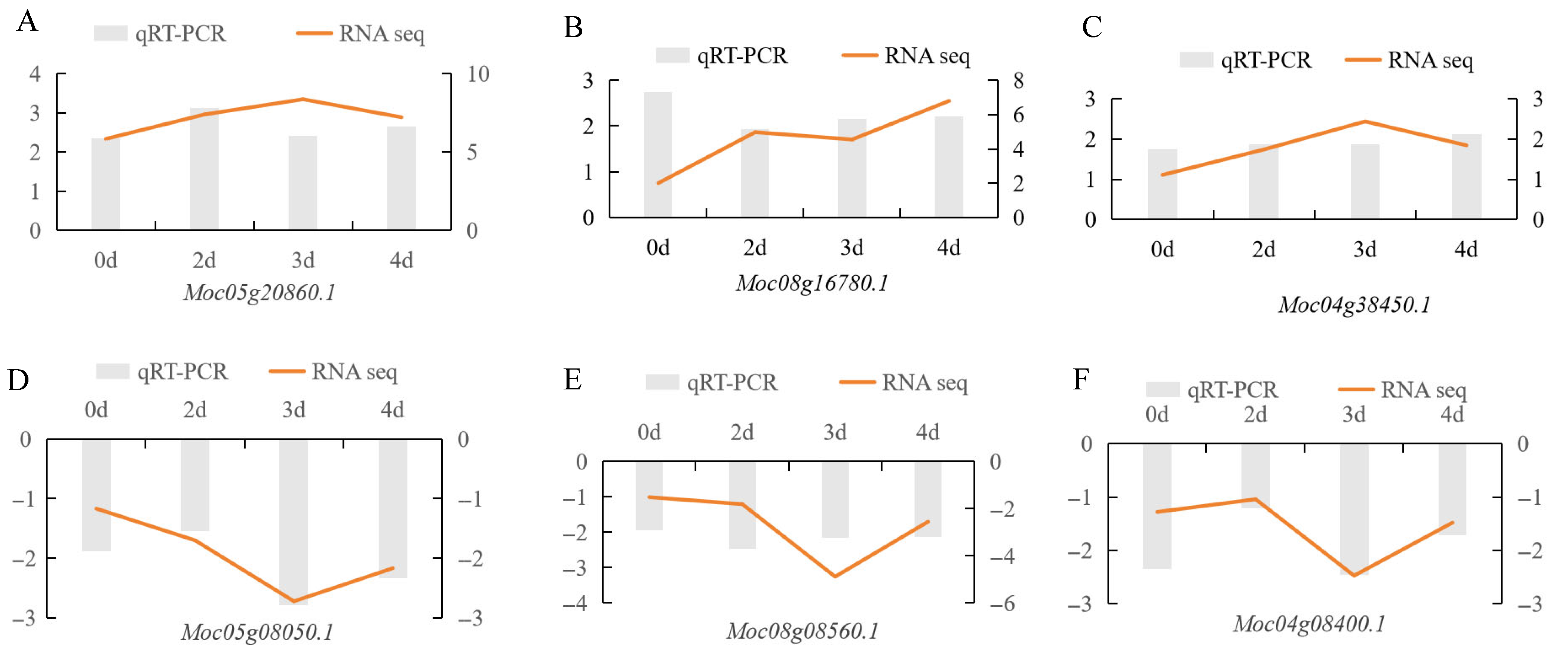

3.7. qRT-PCR Validation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PM | Powdery mildew |

| DEGs | Differentially expressed genes |

| TF | Transcription factor |

| PTI | Pathogen-associated molecular pattern-induced immunity |

| ETI | Effector-induced immunity |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| CML | Calcium-binding proteins |

| CaM | Calmodulin |

| FLS2 | Serine/threonine protein kinase |

| RPM1 | Plant immune receptor protein |

| CNGCs | Cyclic nucleotide-gated channels |

References

- Cheng, Y.; Yao, J.; Zhang, H.; Huang, L.; Kang, Z. Cytological and molecular analysis of nonhost resistance in rice to wheat powdery mildew and leaf rust pathogens. Protoplasma 2015, 252, 1167–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Meng, T.; Xiao, B.; Yu, T.; Yue, T.; Jin, Y.; Ma, P. Fighting wheat powdery mildew: From genes to fields. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2023, 136, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guigón López, C.; Muñoz Castellanos, L.N.; Flores Ortiz, N.A.; González González, J.A. Control of powdery mildew (Leveillula taurica) using trichoderma asperellum and metarhizium anisopliae in different pepper types. BioControl 2019, 64, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadoury, D.M.; Cadle-Davidson, L.; Wilcox, W.F.; Dry, I.A.N.B.; Seem, R.C.; Milgroom, M.G. Grapevine powdery mildew (Erysiphe necator): A fascinating system for the study of the biology, ecology and epidemiology of an obligate biotroph. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2012, 13, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M.; Yu, R.; Yang, W.; Guo, S.; Liu, S.; Du, H.; Liang, J.; Zhang, X. Effect of powdery mildew on the photosynthetic parameters and leaf microstructure of melon. Agriculture 2024, 14, 886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Zhang, J.; Shi, Y.; Nie, C.; Wei, L.; Wang, J. Damage mapping of powdery mildew in winter wheat with high-resolution satellite image. Remote Sens. 2014, 6, 3611–3623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ALDRIGHETTI, A.; PERTOT, I. Epidemiology and control of strawberry powdery mildew: A review. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 2023, 62, 427–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takamatsu, S. Origin and evolution of the powdery mildews (Ascomycota, Erysiphales). Mycoscience 2013, 54, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Romero, C.A.; Palacios-Hernández, E.R.; Muñoz-Minjares, J.U.; Vite-Chávez, O.; Olivera-Reyna, R.; Reyes-Portillo, I.A. Recognition in the early stage of powdery mildew damage for cucurbits plants using spectral signatures. Biosyst. Eng. 2025, 252, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawełkowicz, M.; Głuchowska, A.; Mirzwa-mróz, E.; Zieniuk, B.; Yin, Z.; Zamorski, C.; Przybysz, A. Molecular insights into powdery mildew pathogenesis and resistance in Cucurbitaceous crops. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebeda, A.; Křístková, E.; Sedláková, B.; McCreight, J.D.; Coffey, M.D. Cucurbit powdery mildews: Methodology for objective determination and denomination of races. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2016, 144, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCreight, J.D. Melon-powdery mildew interactions reveal variation in melon cultigens and Podosphaera xanthii Races 1 and 2. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2006, 131, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.-Q.; Niu, H.-Q.; Liu, C.; Wang, H.-L.; Yin, W.; Xia, X. PTI-ETI synergistic signal mechanisms in plant immunity. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2024, 22, 2113–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Liu, S.; Lai, H.-F.; Bender, K.W.; Kim, G.; Caflisch, A.; Zipfel, C. Reverse engineering of the pattern recognition receptor FLS2 reveals key design principles of broader recognition spectra against evading Flg22 epitopes. Nat. Plants 2025, 11, 1642–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albert, M.; Jehle, A.K.; Mueller, K.; Eisele, C.; Lipschis, M.; Felix, G. Arabidopsis thaliana pattern recognition receptors for bacterial elongation factor tu and flagellin can be combined to form functional chimeric receptors*. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 19035–19042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhou, J. Plant immunity triggered by microbial molecular signatures. Mol. Plant 2010, 3, 783–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudsocq, M.; Willmann, M.R.; McCormack, M.; Lee, H.; Shan, L.; He, P.; Bush, J.; Cheng, S.-H.; Sheen, J. Differential innate immune signalling via Ca2+ sensor protein kinases. Nature 2010, 464, 418–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Chen, B.; Guo, Y.; Chen, X.; Li, Q.; Yang, H.; Li, X.; Zhou, J.; Wang, G. Expression of Pumpkin CmbHLH87 Gene Improves powdery mildew resistance in tobacco. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Z.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, L.; Yang, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, L. Transcription factors participate in response to powdery mildew infection in Paeonia lactiflora. Sci. Hortic. 2019, 257, 108535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Wang, H.; Yu, X.; Cui, K.; Hu, Y.; Xiao, S.; Wen, Y.-Q. Transcription factors VviWRKY10 and VviWRKY30 co-regulate powdery mildew resistance in grapevine. Plant Physiol. 2024, 195, 446–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Fang, J.; Yin, W.; Yan, X.; Tu, M.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Z.; Gao, M.; et al. VqWRKY56 interacts with VqbZIPC22 in grapevine to promote proanthocyanidin biosynthesis and increase resistance to powdery mildew. New Phytol. 2023, 237, 1856–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingvardsen, C.R.; Massange-Sánchez, J.A.; Borum, F.; Füchtbauer, W.S.; Bagge, M.; Knudsen, S.; Gregersen, P.L. Highly effective mlo-based powdery mildew resistance in hexaploid wheat without pleiotropic effects. Plant Sci. 2023, 335, 111785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bui, T.P.; Le, H.; Ta, D.T.; Nguyen, C.X.; Le, N.T.; Tran, T.T.; Van Nguyen, P.; Stacey, G.; Stacey, M.G.; Pham, N.B.; et al. Enhancing powdery mildew resistance in soybean by targeted mutation of MLO genes using the CRISPR/Cas9 system. BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, S.; Karati, D. Exploring the Phytochemistry, pharmacognostic properties, and pharmacological activities of medically important plant momordica charantia. Pharmacol. Res.-Mod. Chin. Med. 2023, 6, 100226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, F.; Afzaal, M.; Niaz, B.; Arshad, M.U.; Tufail, T.; Hussain, M.B.; Javed, A. bitter melon (Momordica charantia): A natural healthy vegetable. Int. J. Food Prop. 2018, 21, 1270–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortolotti, M.; Mercatelli, D.; Polito, L.; Efird, J.T. Momordica charantia, a nutraceutical approach for inflammatory related diseases. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zou, K.; Li, X.; Chen, F.; Cheng, Y.; Li, S.; Tian, L. Transcriptomic analysis of the response of susceptible and resistant bitter melon (Momordica charantia L.) to powdery mildew infection revealing complex resistance via multiple signaling pathways. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Diao, Q.; Lu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, D. Comparative transcriptomic analysis of powdery mildew resistant and susceptible melon inbred lines to identify the genes involved in the response to Podosphaera xanthii Infection. Sci. Hortic. 2022, 304, 111305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Dong, W.; Zhao, C.; Ma, H. Comparative Transcriptome analysis of resistant and susceptible Kentucky bluegrass varieties in response to powdery mildew infection. BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Wang, X.; Song, L.; Yao, W.; Guo, M.; Cheng, G.; Guo, J.; Bai, S.; Gao, Y.; Li, J.; et al. Comparative transcriptome and widely targeted metabolome analysis reveals the molecular mechanism of powdery mildew resistance in tomato. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 8236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dun, B.; Zhuo, D.; Shuai, W.; Yane, S.; Yahang, L.; Haonan, C. Allantoin and Jasmonic acid synergistically induce resistance response to powdery mildew in melon as revealed by combined hormone and transcriptome analysis. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 327, 112797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.; Yuan, Y.; Real, N.; Tang, M.; Ren, J.; Wei, J.; Liu, B.; Zhang, X. Fine mapping and identification of candidate genes associated with powdery mildew resistance in melon (Cucumis melo L.). Hortic. Res. 2024, 11, uhae222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary genetics analysis version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wingett, S.W.; Andrews, S. FastQ Screen: A Tool for multi-genome mapping and quality control. F1000Research 2018, 7, 1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.; Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. HISAT: A fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 357–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Smyth, G.K.; Shi, W. FeatureCounts: An efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 923–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varet, H.; Brillet-Guéguen, L.; Coppée, J.-Y.; Dillies, M.-A. SARTools: A DESeq2- and EdgeR-Based R Pipeline for comprehensive differential analysis of RNA-Seq data. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0157022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Thomas, H.R.; Frank, M.H.; He, Y.; Xia, R. TBtools: An Integrative Toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big biological data. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 1194–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, J.; Yuan, Q.; Zhang, W.; Pan, J. Genetics, resistance mechanism, and breeding of powdery mildew resistance in cucumbers (Cucumis sativus L.). Hortic. Plant J. 2023, 9, 603–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Liu, X.; Liu, S.; Li, X.; Xue, L.; Bai, T.; Xu, B.; Li, G.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, X. Fine mapping of ClLOX, a QTL for Powdery mildew resistance in watermelon (Citrullus lanatus L.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 2024, 137, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabet, H.; Asadi-Gharneh, H.A.; Nasr-Esfahani, M. Butternut Pumpkin-powdery mildew disease interaction as influenced by sowing type and date. Ecol. Genet. Genom. 2025, 36, 100375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Wang, L. Hyperspectral monitoring of powdery mildew disease severity in wheat based on machine learning. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 828454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kousik, C.S.; Ikerd, J.L. Physiological races of cucurbit powdery mildew pathogen (Podosphaera xanthii) based on watermelon differentials. Plant Health Prog. 2025, 26, 308–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Yao, D.; Diao, Q.; Tian, S.; Lv, D.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y. Integrated physiological, transcriptome and metabolome analysis revealed the response mechanisms of melon to Podosphaera xanthii. Plant Stress 2025, 18, 101070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Zhang, M.; Zhuo, Z.; Wang, Y.; Gao, X.; Li, Y.; Liu, W.; Zhang, W. Transcriptome Profiling analysis reveals distinct resistance response of cucumber leaves infected with Powdery mildew. Plant Biol. 2021, 23, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, X.; Guo, C.; Gao, M.; Li, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Lu, H.; et al. A module with multiple transcription factors positively regulates powdery mildew resistance in Grapevine. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2025, 23, 3984–3999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Pan, Y.; Hao, X.; Guo, C.; Wang, X.; Yan, X.; Guo, R. Overexpression of a grapevine VqWRKY2 transcription factor in Arabidopsis Thaliana increases resistance to powdery mildew. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2024, 157, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; You, H.; Li, H.; Zhang, C.; Guo, H.; Huang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Ma, C.; Wang, Y.; et al. TaNAC1 boosts powdery mildew resistance by phosphorylation-dependent regulation of TaSec1a and TaCAMTA4 via PP2Ac/CDPK20. New Phytol. 2024, 244, 635–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Liu, M.; Wang, L.; Tong, P.; Xing, Q.; Qi, H. An Ethylene response factor negatively regulates red light induced resistance of melon to powdery mildew by inhibiting ethylene biosynthesis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 307, 141867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreiseitl, A. Major genes for powdery mildew resistance in research and breeding of barley: A few brief narratives and recommendations. Plants 2025, 14, 2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, D.-Y.; Guo, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Hu, Y.; Xiao, S.; Wang, Y.; Wen, Y.-Q. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated mutagenesis of VvMLO3 results in enhanced resistance to powdery mildew in grapevine (Vitis vinifera). Hortic. Res. 2020, 7, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Yang, L.; Hu, Z.; Mo, C.; Geng, S.; Zhao, X.; He, Q.; Xiao, L.; Lu, L.; Wang, D.; et al. Multiplex gene editing reveals cucumber mildew resistance locus O family roles in powdery mildew resistance. Plant Physiol. 2024, 195, 1069–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Liu, J.; Liu, Z.; Xia, P.; Yuan, X.; Ning, Y. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of the MLO Gene Family reveal a candidate gene associated with powdery mildew susceptibility in bitter gourd (Momordica charantia). Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2021, 159, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, F.; Lan, Y.; Zhang, T.; Li, C.; Li, Y.; Xia, F.; Liu, X. Genome-wide analysis of Mlo Genes and functional characterization of Cm-Mlo38 and Cm-Mlo44 in regulating powdery mildew resistance in melon. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Xu, X.; Shi, Y.; Qi, X.; Chen, X. Elucidation of the Molecular Responses of a cucumber segment substitution line carrying Pm5.1 and its recurrent parent triggered by powdery mildew by comparative transcriptome profiling. BMC Genom. 2017, 18, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Raw Bases | Clean Bases | Q20 Rate | Q30 Rate | Total Mapped (%) | Unique Mapped (%) | Multiple Mapped (%) | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1-1 | 6,422,622,599 | 6,422,621,067 | 99.59% | 98.14% | 95.29 | 93.32 | 1.97 | S leaves from 0 d after P. xanthii infection, replicate 1 |

| S1-2 | 6,406,034,319 | 6,406,032,606 | 99.57% | 98.09% | 95.45 | 92.94 | 2.51 | S leaves from 0 d after P. xanthii infection, replicate 2 |

| S1-3 | 6,423,245,294 | 6,423,244,200 | 99.55% | 98.00% | 95.05 | 91.9 | 3.15 | S leaves from 0 d after P. xanthii infection, replicate 3 |

| S2-1 | 5,949,178,756 | 5,949,178,030 | 99.52% | 98.20% | 97.08 | 91.08 | 6 | S leaves from 2 d after P. xanthii infection, replicate 1 |

| S2-2 | 5,660,981,999 | 5,660,981,348 | 99.53% | 98.22% | 94.83 | 89.39 | 5.44 | S leaves from 2 d after P. xanthii infection, replicate 2 |

| S2-3 | 6,046,311,957 | 6,046,311,577 | 99.51% | 98.14% | 97.43 | 91.38 | 6.05 | S leaves from 2 d after P. xanthii infection, replicate 3 |

| S3-1 | 6,379,142,585 | 6,379,142,095 | 99.57% | 98.12% | 94.72 | 88.63 | 6.09 | S leaves from 3 d after P. xanthii infection, replicate 1 |

| S3-2 | 6,398,157,856 | 6,398,157,391 | 99.56% | 98.09% | 93.32 | 88.19 | 5.13 | S leaves from 3 d after P. xanthii infection, replicate 2 |

| S3-3 | 6,424,807,168 | 6,424,806,843 | 99.58% | 98.14% | 95.52 | 89.4 | 6.12 | S leaves from 3 d after P. xanthii infection, replicate 3 |

| S4-1 | 6,387,274,092 | 6,387,273,654 | 99.59% | 98.22% | 93.46 | 87.91 | 5.55 | S leaves from 4 d after P. xanthii infection, replicate 1 |

| S4-2 | 6,415,222,101 | 6,415,221,598 | 99.57% | 98.12% | 93.19 | 87.91 | 5.28 | S leaves from 4 d after P. xanthii infection, replicate 2 |

| S4-3 | 6,428,912,939 | 6,428,912,577 | 99.55% | 98.04% | 93.13 | 86.26 | 6.87 | S leaves from 4 d after P. xanthii infection, replicate 3 |

| R1-1 | 5,844,186,424 | 5,844,186,118 | 99.41% | 97.80% | 91.97 | 84.42 | 7.55 | R leaves from 0 d after P. xanthii infection, replicate 1 |

| R1-2 | 6,079,347,055 | 6,079,346,832 | 99.48% | 98.04% | 92.82 | 82.24 | 10.58 | R leaves from 0 d after P. xanthii infection, replicate 2 |

| R1-3 | 6,393,222,007 | 6,393,221,515 | 99.68% | 98.65% | 89.43 | 81.07 | 8.36 | R leaves from 0 d after P. xanthii infection, replicate 3 |

| R2-1 | 5,929,993,595 | 5,929,993,216 | 99.60% | 98.35% | 91.98 | 83.91 | 8.07 | R leaves from 2 d after P. xanthii infection, replicate 1 |

| R2-2 | 6,444,837,279 | 6,444,837,035 | 99.69% | 98.68% | 91.53 | 82.26 | 9.27 | R leaves from 2 d after P. xanthii infection, replicate 2 |

| R2-3 | 6,423,554,130 | 6,423,553,643 | 99.61% | 98.24% | 92.91 | 82.94 | 9.97 | R leaves from 2 d after P. xanthii infection, replicate 3 |

| R3-1 | 6,427,115,185 | 6,427,114,836 | 99.67% | 98.61% | 91.31 | 80.98 | 10.33 | R leaves from 3 d after P. xanthii infection, replicate 1 |

| R3-2 | 6,205,242,855 | 6,205,242,397 | 99.61% | 98.48% | 91.96 | 82.98 | 8.98 | R leaves from 3 d after P. xanthii infection, replicate 2 |

| R3-3 | 6,444,806,901 | 6,444,806,713 | 99.59% | 98.18% | 95.96 | 85.96 | 10 | R leaves from 3 d after P. xanthii infection, replicate 3 |

| R4-1 | 6,412,320,897 | 6,412,320,493 | 99.63% | 98.33% | 94.09 | 85.48 | 8.61 | R leaves from 4 d after P. xanthii infection, replicate 1 |

| R4-2 | 6,441,096,616 | 6,441,096,338 | 99.56% | 98.08% | 91.8 | 86.13 | 5.67 | R leaves from 4 d after P. xanthii infection, replicate 2 |

| R4-3 | 6,443,186,760 | 6,443,186,330 | 99.59% | 98.23% | 91.37 | 87.15 | 4.22 | R leaves from 4 d after P. xanthii infection, replicate 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Xia, L.; Wang, K.; Guan, F.; Shi, B.; Yang, X.; Xie, Y.; Wan, X.; Zhang, J. Morphology and Comparative Transcriptome Analysis of Resistant and Susceptible Bitter Gourd (Momordica charantia L.) Reveals the Molecular Response Related to Powdery Mildew Resistance. J. Fungi 2026, 12, 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof12010080

Xia L, Wang K, Guan F, Shi B, Yang X, Xie Y, Wan X, Zhang J. Morphology and Comparative Transcriptome Analysis of Resistant and Susceptible Bitter Gourd (Momordica charantia L.) Reveals the Molecular Response Related to Powdery Mildew Resistance. Journal of Fungi. 2026; 12(1):80. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof12010080

Chicago/Turabian StyleXia, Lei, Kai Wang, Feng Guan, Bo Shi, Xuetong Yang, Yuanyuan Xie, Xinjian Wan, and Jingyun Zhang. 2026. "Morphology and Comparative Transcriptome Analysis of Resistant and Susceptible Bitter Gourd (Momordica charantia L.) Reveals the Molecular Response Related to Powdery Mildew Resistance" Journal of Fungi 12, no. 1: 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof12010080

APA StyleXia, L., Wang, K., Guan, F., Shi, B., Yang, X., Xie, Y., Wan, X., & Zhang, J. (2026). Morphology and Comparative Transcriptome Analysis of Resistant and Susceptible Bitter Gourd (Momordica charantia L.) Reveals the Molecular Response Related to Powdery Mildew Resistance. Journal of Fungi, 12(1), 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof12010080