Zinc-Finger 5 Is an Activation Domain in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Stress-Responsive Transcription Factor Fzf1

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Yeast Strains, Cell Culture, and Chemical Treatments

2.2. Plasmid Construction and Site-Specific Mutagenesis

2.3. Yeast Cell Transformation

2.4. Yeast Survival Assay

2.5. Yeast RNA Extraction and Quantitative Reverse Transcription PCR (qRT-PCR)

2.6. Western Blot Analysis

2.7. Yeast Reporter Gene Assays

2.8. Recombinant Fzf1-N117 Protein Production and Purification

2.9. Electrophoresis Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA)

3. Results

3.1. fzf1-ZF5 Is Intragenically Epistatic to fzf1-ZF4

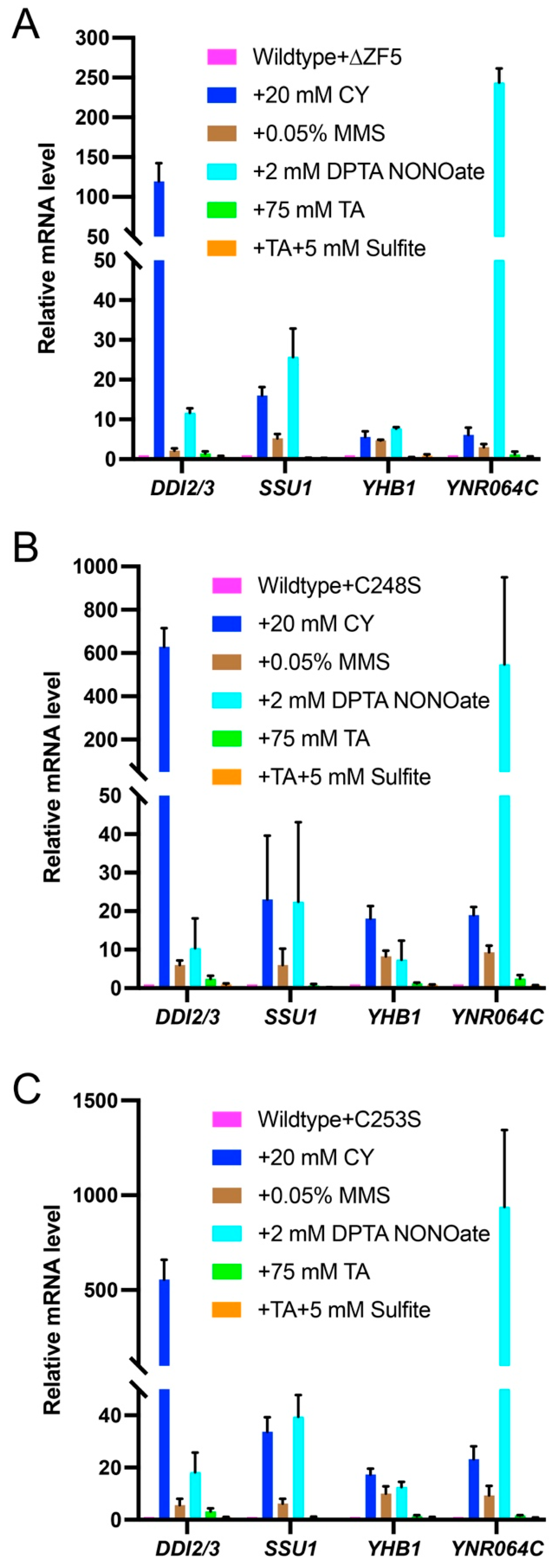

3.2. fzf1-C248S and fzf1-C253S Differentially Affect Fzf1-Regulated Gene Expressions in Response to Chemical Stresses

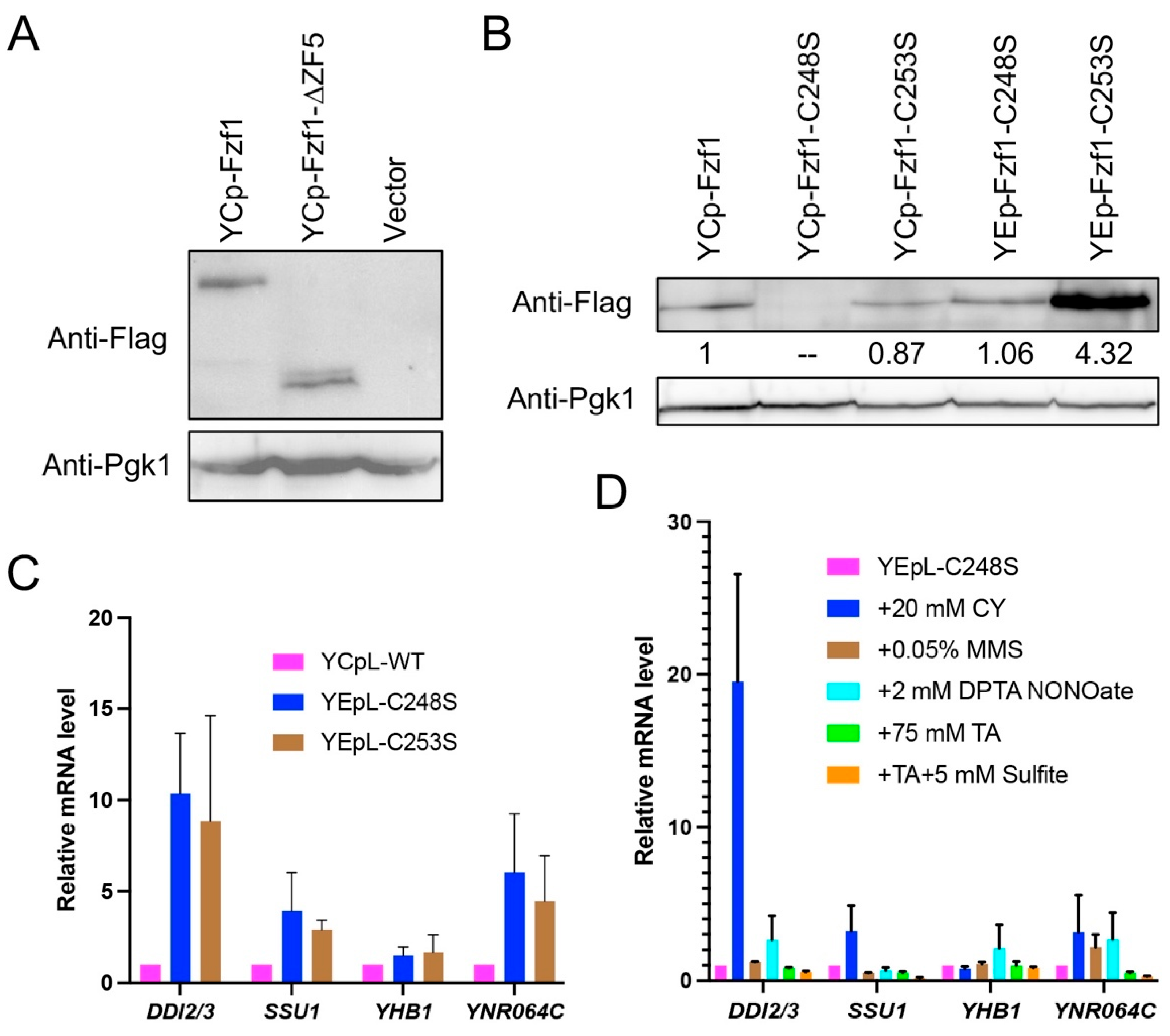

3.3. FZF1 Is Dominant over fzf1-ZF5 Mutations

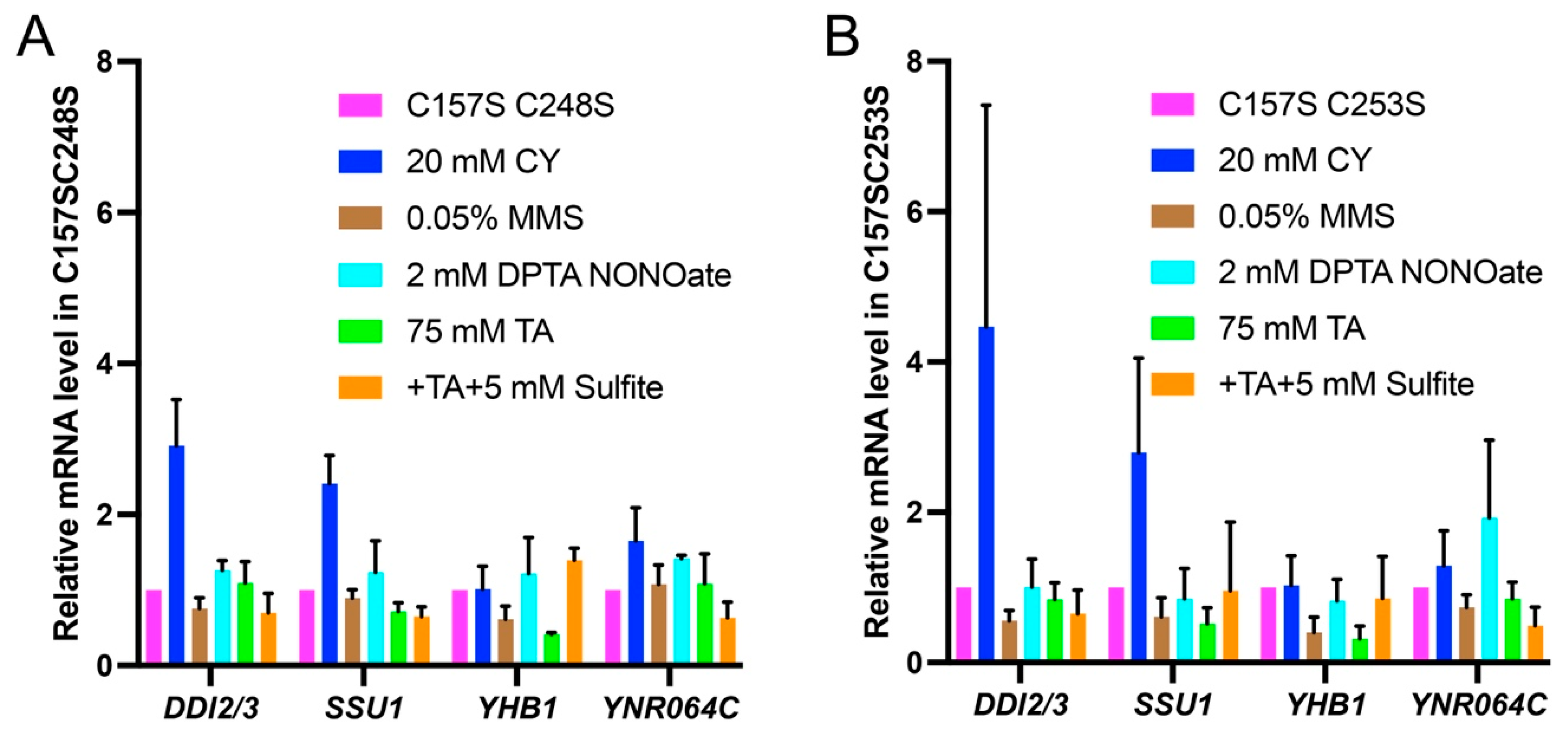

3.4. fzf1-ZF5 Mutations Are Epistatic to fzf1-ZF4 in Response to Chemical Stresses

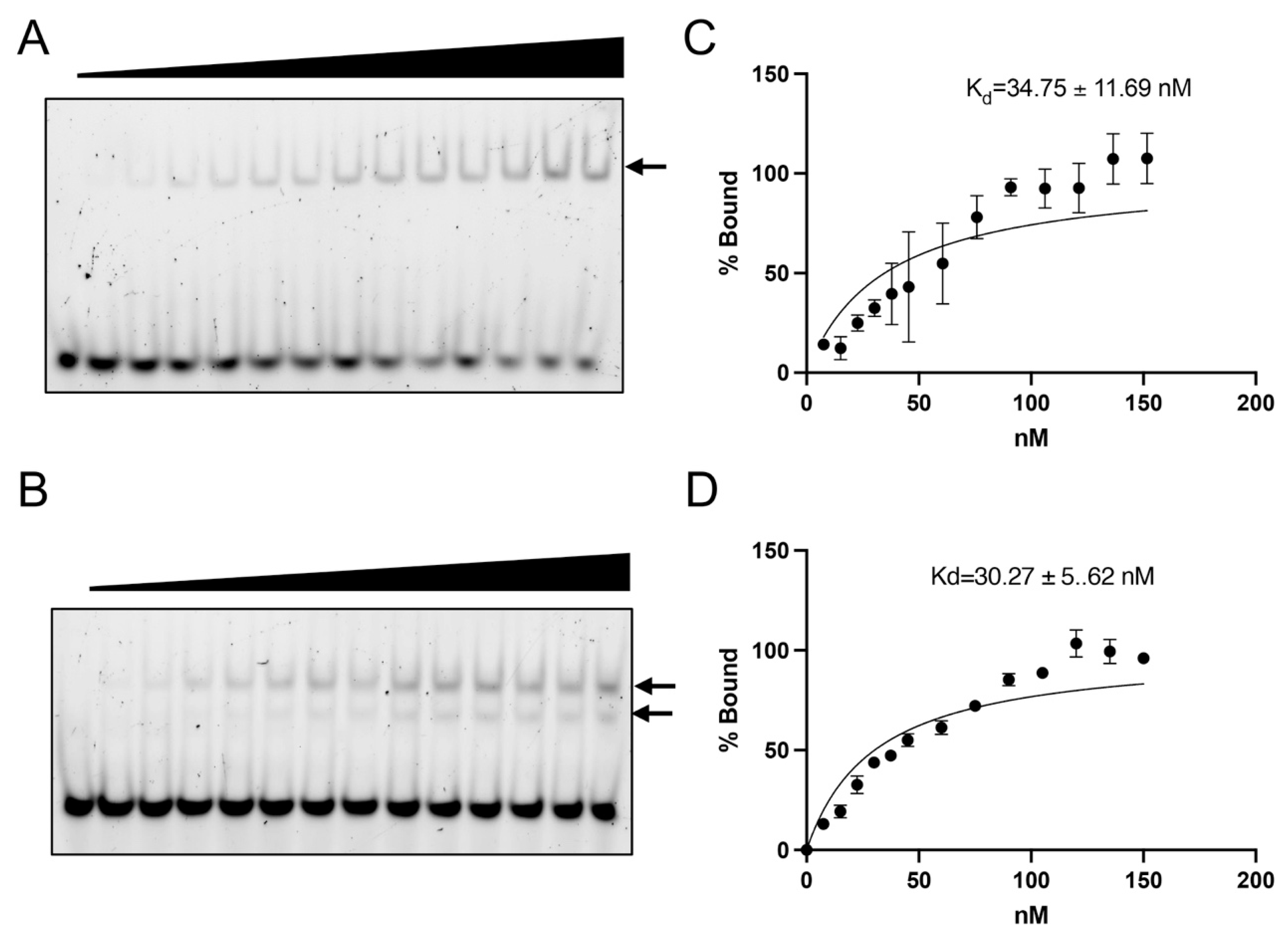

3.5. ZF5 Is Dispensable for the Fzf1 Target Sequence CS2 Recognition

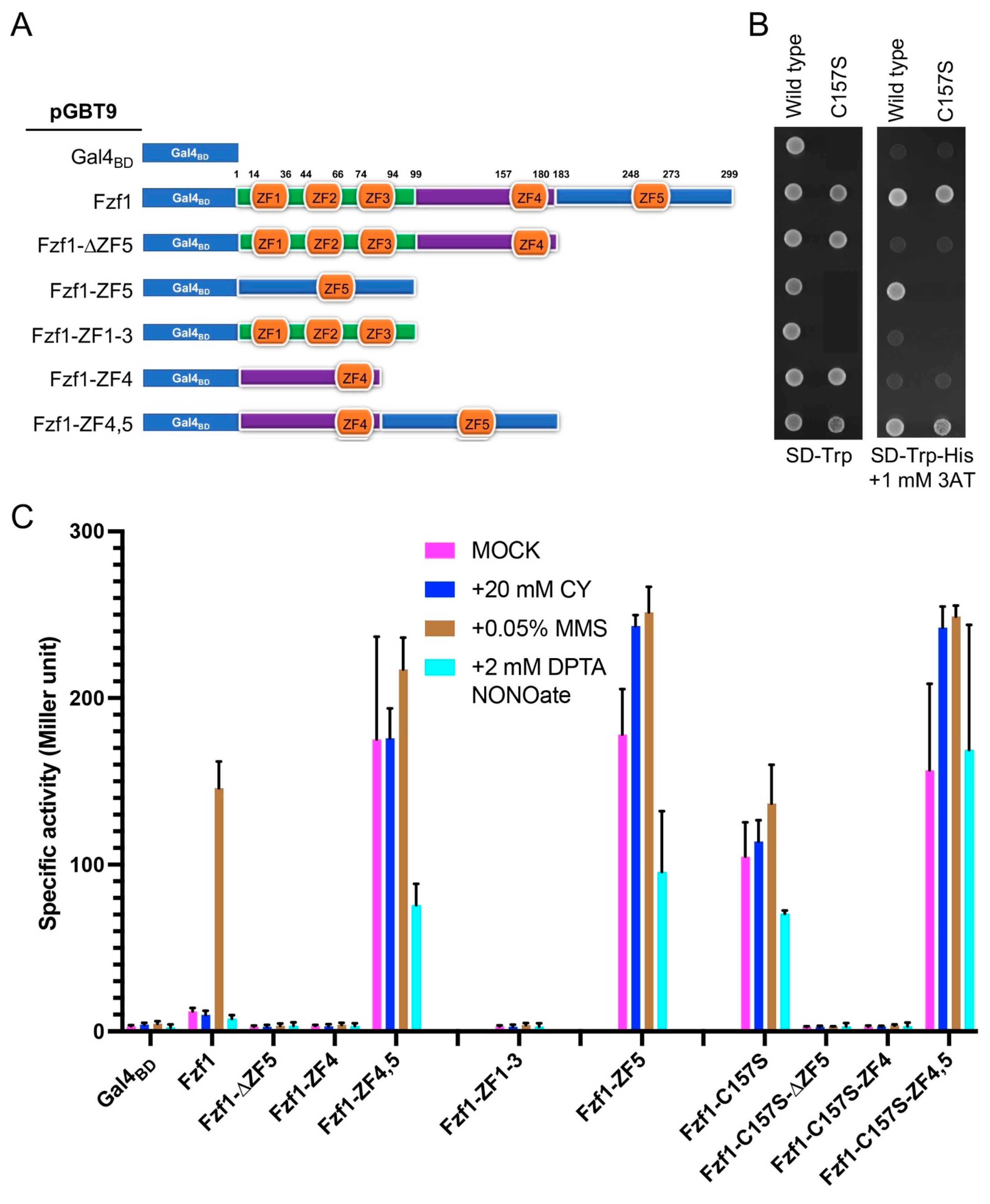

3.6. The Fzf1-ZF5 Domain Can Function Independently of the Fzf1 DNA-Binding Domain

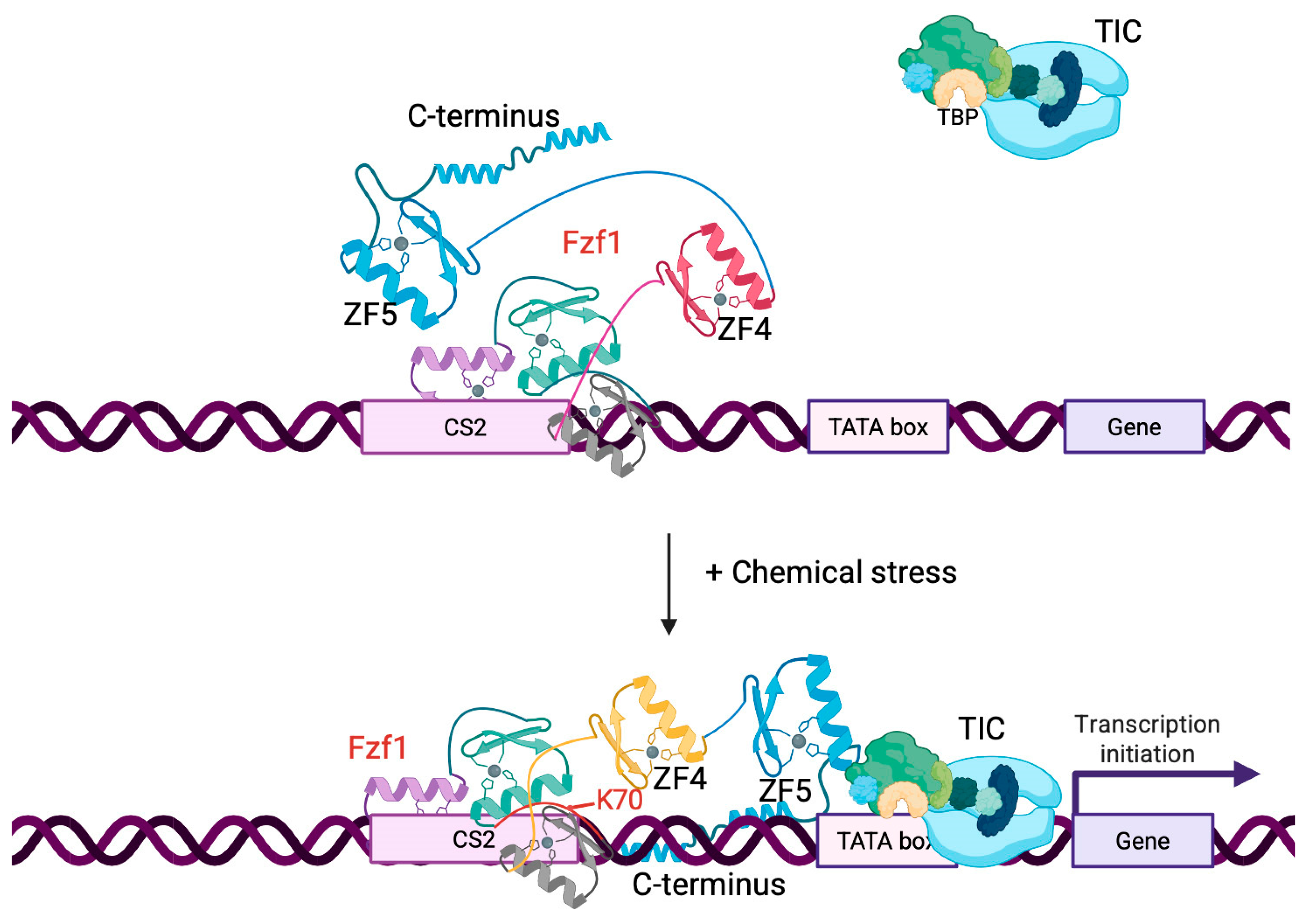

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Breitwieser, W.; Price, C.; Schuster, T. Identification of a gene encoding a novel zinc finger protein in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 1993, 9, 551–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarver, A.; DeRisi, J. Fzf1p regulates an inducible response to nitrosative stress in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell 2005, 16, 4781–4791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Ma, C.; Moore, S.A.; Xiao, W. Zinc finger 4 negatively controls the transcriptional activator Fzf1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. mLife 2024, 3, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avram, D.; Bakalinsky, A.T. SSU1 encodes a plasma membrane protein with a central role in a network of proteins conferring sulfite tolerance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Bacteriol. 1997, 179, 5971–5974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buisson, N.; Labbe-Bois, R. Flavohemoglobin expression and function in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. No relationship with respiration and complex response to oxidative stress. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 9527–9533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horan, S.; Bourges, I.; Meunier, B. Transcriptional response to nitrosative stress in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 2006, 23, 519–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier-Greiner, U.H.; Obermaier-Skrobranek, B.M.; Estermaier, L.M.; Kammerloher, W.; Freund, C.; Wulfing, C.; Burkert, U.I.; Matern, D.H.; Breuer, M.; Eulitz, M.; et al. Isolation and properties of a nitrile hydratase from the soil fungus Myrothecium verrucaria that is highly specific for the fertilizer cyanamide and cloning of its gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1991, 88, 4260–4264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Biss, M.; Fu, Y.; Xu, X.; Moore, S.A.; Xiao, W. Two duplicated genes DDI2 and DDI3 in budding yeast encode a cyanamide hydratase and are induced by cyanamide. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 12664–12675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, A.; Zeng, C.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, W.; Li, M.; Hanna, M.; Xiao, W. Utilization of a Strongly Inducible DDI2 Promoter to Control Gene Expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, K.; Yeung, M.; Durocher, D.; Xiao, W. Rad6-Rad18 mediates a eukaryotic SOS response by ubiquitinating the 9-1-1 checkpoint clamp. Cell 2008, 133, 601–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Bartels, M.J.; Pottenger, L.H.; Gollapudi, B.B. Differential adduction of proteins vs. deoxynucleosides by methyl methanesulfonate and 1-methyl-1-nitrosourea in vitro. Rapid Commun. Mass. Spectrom. 2005, 19, 438–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfstrom, L.T.; Widersten, M. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae ORF YNR064c protein has characteristics of an ‘orphaned’ epoxide hydrolase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2005, 1748, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, A.; Chumala, P.; Du, Y.; Ma, C.; Wei, T.; Xu, X.; Luo, Y.; Katselis, G.S.; Xiao, W. Transcriptional activation of budding yeast DDI2/3 through chemical modifications of Fzf1. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 2023, 39, 1531–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Du, Y.; Xiao, W.; Moore, S.A. Zn-finger transcription factor Fzf1 binds to its target DNA in a non-canonical manner. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025. in revision. [Google Scholar]

- Laity, J.H.; Lee, B.M.; Wright, P.E. Zinc finger proteins: New insights into structural and functional diversity. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2001, 11, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aceituno-Valenzuela, U.; Micol-Ponce, R.; Ponce, M.R. Genome-wide analysis of CCHC-type zinc finger (ZCCHC) proteins in yeast, Arabidopsis, and humans. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2020, 77, 3991–4014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razin, S.V.; Borunova, V.V.; Maksimenko, O.G.; Kantidze, O.L. Cys2His2 zinc finger protein family: Classification, functions, and major members. Biochemistry 2012, 77, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avram, D.; Leid, M.; Bakalinsky, A.T. Fzf1p of Saccharomyces cerevisiae is a positive regulator of SSU1 transcription and its first zinc finger region is required for DNA binding. Yeast 1999, 15, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casalone, E.; Colella, C.M.; Daly, S.; Fontana, S.; Torricelli, I.; Polsinelli, M. Cloning and characterization of a sulphite-resistance gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 1994, 10, 1101–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasuno, R.; Yoshioka, N.; Yoshikawa, Y.; Takagi, H. Cysteine residues in the fourth zinc finger are important for activation of the nitric oxide-inducible transcription factor Fzf1 in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes. Cells 2021, 26, 823–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, F.; Fink, G.R.; Hicks, J. Methods in Yeast Genetics; Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press: Cold Spring Harbor, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Naismith, J.H. An efficient one-step site-directed deletion, insertion, single and multiple-site plasmid mutagenesis protocol. BMC Biotechnol. 2008, 8, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, H.; Fukuda, Y.; Murata, K.; Kimura, A. Transformation of intact yeast cells treated with alkali cations. J. Bacteriol. 1983, 153, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gietz, R.D.; Woods, R.A. Yeast transformation by the LiAc/SS Carrier DNA/PEG method. Methods Mol. Biol. 2006, 313, 107–120. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Lambrecht, A.D.; Xiao, W. In Yeast Protocols, Xiao, W., Ed.; Yeast survival and growth assays, 3rd ed.; Humana Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014; Volume 1163, pp. 183–191. [Google Scholar]

- Schmittgen, T.D.; Livak, K.J. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat. Protoc. 2008, 3, 1101–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gietz, R.D.; Sugino, A. New yeast-Escherichia coli shuttle vectors constructed with in vitro mutagenized yeast genes lacking six-base pair restriction sites. Gene 1988, 74, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Xue, H.; Li, S.; Chen, Y.; Tian, X.; Xu, X.; Xiao, W.; Fu, Y.V. A method for labeling proteins with tags at the native genomic loci in budding yeast. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0176184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, L.G.; Xiao, W. Xiao, W., Ed.; Detection of protein posttranslational modifications from whole-cell extracts in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. In Yeast Protocols, 3rd ed.; Humana Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014; Volume 1163, pp. 249–255. [Google Scholar]

- Fields, S.; Song, O. A novel genetic system to detect protein-protein interactions. Nature 1989, 340, 245–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, P.; Halladay, J.; Craig, E.A. Genomic libraries and a host strain designed for highly efficient two-hybrid selection in yeast. Genetics 1996, 144, 1425–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biss, M.; Xiao, W. Yan, Z., Caldwell, G.W., Eds.; Assessing DNA damage using a reporter gene system. In Optimization in Drug Discovery; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J. Transcriptional activators and activation mechanisms. Protein Cell 2011, 2, 879–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ptashne, M. How eukaryotic transcriptional activators work. Nature 1988, 335, 683–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmorstein, R.; Carey, M.; Ptashne, M.; Harrison, S.C. DNA recognition by GAL4: Structure of a protein-DNA complex. Nature 1992, 356, 408–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paik, W.K.; DiMaria, P.; Kim, S.; Magee, P.N.; Lotlikar, P.D. Alkylation of protein by methyl methanesulfonate and 1-methyl-1-nitrosourea in vitro. Cancer Lett. 1984, 23, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amberger, A. Cyanamide in plant metabolism. Int. J. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2013, 5, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.Y.; Chu, H.M.; Pan, K.T.; Teng, C.H.; Wang, D.L.; Wang, A.H.; Khoo, K.H.; Meng, T.C. Cysteine S-nitrosylation protects protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1B against oxidation-induced permanent inactivation. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 35265–35272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, B.; Pan, Q.; Clarke, D.; Villarreal, M.O.; Umbreen, S.; Yuan, B.; Shan, W.; Jiang, J.; Loake, G.J. S-nitrosylation of the zinc finger protein SRG1 regulates plant immunity. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, D.T.; Matsumoto, A.; Kim, S.O.; Marshall, H.E.; Stamler, J.S. Protein S-nitrosylation: Purview and parameters. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005, 6, 150–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erkine, A.M.; Oliveira, M.A.; Class, C.A. The Enigma of Transcriptional Activation Domains. J. Mol. Biol. 2024, 436, 168766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udupa, A.; Kotha, S.R.; Staller, M.V. Commonly asked questions about transcriptional activation domains. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2024, 84, 102732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeh, A.; Baran, D.; Volokh, M.; Aharoni, A. Conserved motifs in the Msn2-activating domain are important for Msn2-mediated yeast stress response. J. Cell Sci. 2012, 125, 3333–3342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piskacek, M.; Havelka, M.; Rezacova, M.; Knight, A. The 9aaTAD Transactivation Domains: From Gal4 to p53. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0162842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beishline, K.; Azizkhan-Clifford, J. Sp1 and the ‘hallmarks of cancer’. FEBS J. 2015, 282, 224–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, M.P. The structure and function of proline-rich regions in proteins. Biochem. J. 1994, 297, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mermod, N.; O’Neill, E.A.; Kelly, T.J.; Tjian, R. The proline-rich transcriptional activator of CTF/NF-I is distinct from the replication and DNA binding domain. Cell 1989, 58, 741–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iuchi, S. Three classes of C2H2 zinc finger proteins. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2001, 58, 625–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Du, Y.; Wang, W.Y.; Xiao, W. Zinc-Finger 5 Is an Activation Domain in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Stress-Responsive Transcription Factor Fzf1. J. Fungi 2026, 12, 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof12010015

Du Y, Wang WY, Xiao W. Zinc-Finger 5 Is an Activation Domain in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Stress-Responsive Transcription Factor Fzf1. Journal of Fungi. 2026; 12(1):15. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof12010015

Chicago/Turabian StyleDu, Ying, Wayne Y. Wang, and Wei Xiao. 2026. "Zinc-Finger 5 Is an Activation Domain in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Stress-Responsive Transcription Factor Fzf1" Journal of Fungi 12, no. 1: 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof12010015

APA StyleDu, Y., Wang, W. Y., & Xiao, W. (2026). Zinc-Finger 5 Is an Activation Domain in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Stress-Responsive Transcription Factor Fzf1. Journal of Fungi, 12(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof12010015