Attributable Mortality to Candidiasis in Non-Neutropenic Critically Ill Patients in the ICU and a Post-Mortem Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

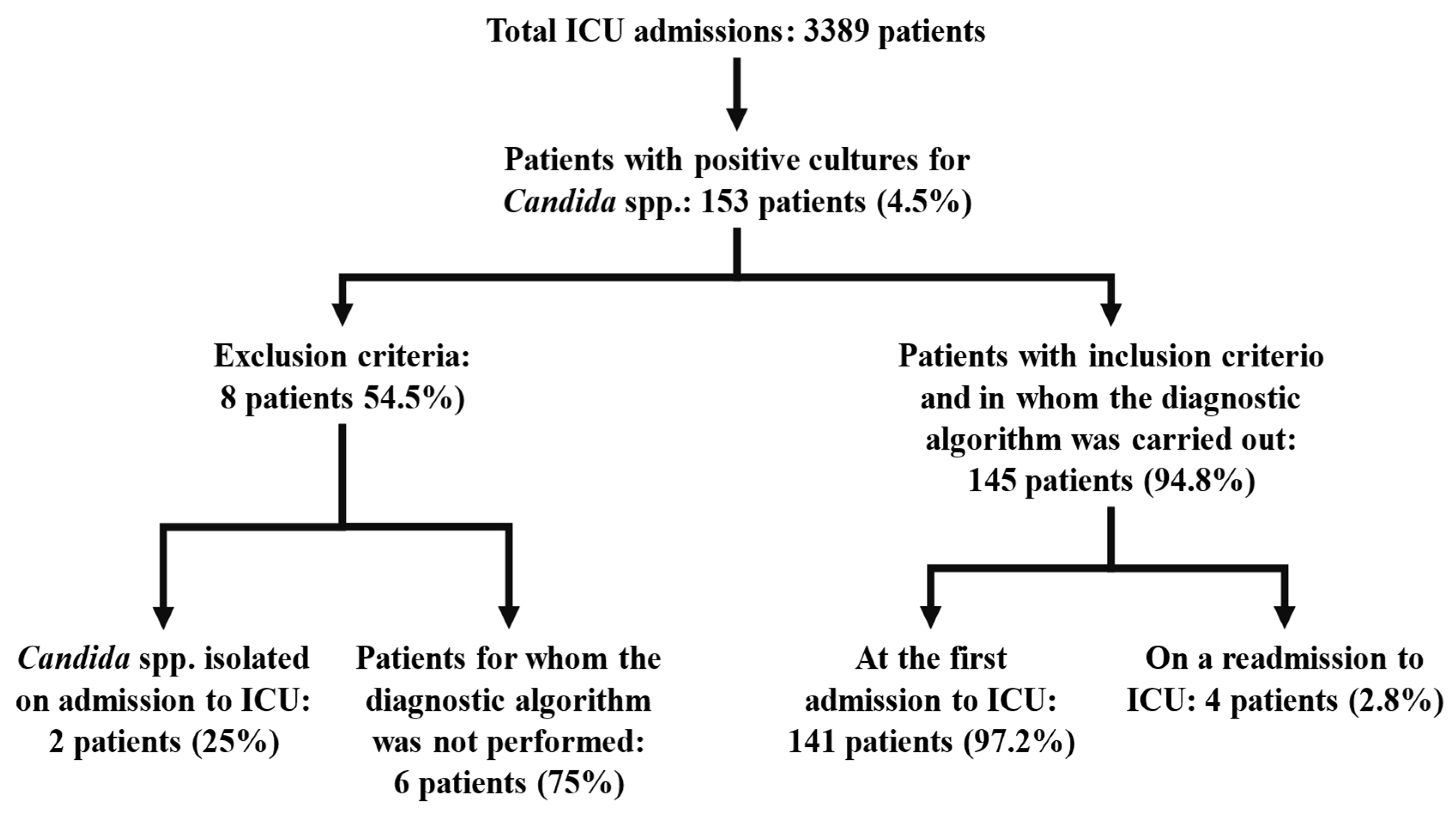

2. Materials and Methods

- (a)

- Heart, liver, spleen, and brain: The presence of yeast in histology is associated with polymorphonuclear inflammatory foci in different areas of the parenchyma studied.

- (b)

- Blood and spleen: Cultures were obtained by puncturing cardiac cavities or splenic parenchyma with a sterile needle and prior cauterization of the puncture point.

- (c)

- Intestine: The presence of pseudohyphae or hyphae in histology that extend to the muscle and/or serosa, together with the presence of an important polymorphonuclear infiltrate. The culture was assessed from samples obtained from the peritoneal cavity or bile fluid.

- (d)

- Lung: Histology is evaluated if pseudohyphae and spores are found in the parenchyma, alveoli, and vessels, along with polymorphonuclear infiltrates. The culture was obtained from areas of the parenchyma distant from the main bronchi and trachea.

- (e)

- Kidneys: The presence of yeast with a polymorphonuclear inflammatory component in the kidney parenchyma. The culture was obtained from areas of the parenchyma and not from the urinary tract.

- (f)

- When the culture tests positive for yeasts in isolation form in the trachea, main Bronchi, or urine obtained by bladder puncture, it is considered an indicator of colonization in the post-mortem study, but not of IC.

- Death was attributable to yeast when

- Cultures and histology were positive for yeast;

- Negative cultures and positive histology for yeast were observed in more than one organ;

- Negative histology and positive cultures for yeast were observed in significant organs, without identification of other microorganisms.

- Yeast was not considered as a cause of death when

- Cultures and histology were negative for yeast;

- Negative cultures and positive histology for yeast were observed in a single organ, such as the liver, spleen, intestine, kidney, or lungs;

- Negative histology and cultures positive for yeast were observed in significant organs, with identification of other microorganisms that may be considered responsible for death.

- Attributable mortality according to the post-mortem study: This is the resulting analysis of deceased patients who, on post-mortem study, show death attributable to yeast and to respiratory failure, sepsis, or Multiple Organ Dysfunction Syndrome (MODS). The “gold standard” for the diagnosis of invasive candidiasis is biopsy [19] or post-mortem study [13].

- Attributable mortality according to clinical study: This includes deaths in which a post-mortem study was not performed. The group of patients with a moderate probability of death attributable to yeast is defined based on the clinical cause of death, the existence of multifocal yeast isolates, and incomplete antifungal treatment (<5 days) before death.

- Crude mortality rate: This refers to the attributable mortality resulting from the sum of the cases defined as attributable mortality from the post-mortem study and those defined as attributable mortality from the clinical study.

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ho, M.M. Non-Bacterial Infections in the ICU; Dhoemaker, W.C., Thompson, W.L., Eds.; Critical Care. State of the Art; Society of Critical Care Medicine: Fullerton, CA, USA, 1981; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Bassetti, M.; Giacobbe, D.R.; Agvald-Ohman, C.; Akova, M.; Alastruey-Izquierdo, A.; Arikan-Akdagli, S.; Azoulay, E.; Blot, S.; Cornely, O.A.; Cuenca-Estrella, M.; et al. Invasive Fungal Diseases in Adult Patients in intensive care unit (FUNDICU): 2024 consensus definitions from ESGCIP, EFISG, ESICM, ECMM, MSGERC, ISAC, and ISHAM. Intensive Care Med. 2024, 50, 502–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León Regidor, M.A.; Ayuso Gatell, A.; Díaz Boladeras, R.; Robusté Morell, J.; Soria Guerrero, G.; Torres de Dalmases, C.; Torres Rodríguez, J.M.; Nolla Salas, M. Candidiasis in an intensive care unit. Rev. Clin. Esp. 1993, 193, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- von Cube, M.; Timsit, J.F.; Schumacher, M.; Motschall, E.; Schumacher, M. Quantification and interpretation of attributable mortality in core clinical infectious disease journals. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, e299–e306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lefemine, A.; Acuff, R.; Vo, N.; Waycaster, M. Delayed hypersentivity on a surgical service. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 1988, 7, 355–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, A.P.; McCluskey, D.R. Assessment of cell-mediated immunity in a British population using multiple skin test antigens. Clin. Exp. Allerg. 1986, 16, 365–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, R.G. Prospective study of Candida endophthalmitis in hospitalized patients with candidemia. Arch. Intern. Med. 1989, 149, 2226–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez-Nolla, J.; Nolla-Salas, M. Multifocal Candidiasis can be considered a form of Invasive Candidiasis in critically non neutropenic patients. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2024, 147, 107171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balows, A.; Harsler, W.J. Manual of Clinical Microbiology, 5th ed.; Section III; American Society for Microbiology: Washington, DC, USA, 1991; pp. 209–553. [Google Scholar]

- Dolan, C.T.; Brown, A.L.; Ritts, R.E. Microbiological examination of postmortem tissues. Arch. Pathol. 1971, 92, 206–211. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ludwig, J. Current Methods of Autopsy Practice; Sunders Company WB: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Bodey, G.; Bueltmann, B.; Duguid, W.; Gibbs, D.; Hanak, H.; Hotchi, M.; Mall, G.; Martino, P.; Meunier, F.; Milliken, S.; et al. Fungal infections in cancer patients: An International Autopsy Survey. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 1992, 11, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, W.T. Systemic candidiasis. A study of 109 fatal cases. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. 1982, 1, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Moulin, G.C.; Paterson, D.G. Clinical relevance of postmortem microbiologic examination: A review. Hum. Pathol. 1985, 16, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín Álvarez, R.; Pérez Sáenz, J.L. Microbiología postmortem. Med. Clin. 1983, 81, 667–669. [Google Scholar]

- Jandrlic, M.; Kalenic, S.; Labar, B.; Nemet, D.; Jakic-Razumovic, J.; Mrsic, M.; Plecko, V.; Bogdanic, V. An autopsy study of systemic fungal infections in patients with hematologic malignancies. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 1995, 14, 768–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeGregorio, M.W.; Lee, W.M.F.; Linker, C.A.; Jacobs, R.A.; Ries, C.A. Fungal infections in patients with acute leukemia. Am. J. Med. 1982, 73, 543–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myerowitz, R.L.; Pazin, G.J.; Allen, C.M. Disseminated candidiasis. Changes in incidence, underlying diseases and pathology. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 1977, 68, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, C.; Metry, M. Life-threatening Candida infections in the intensive care unit. J. Intensive Care Med. 1992, 7, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittet, D.; Tarara, D.; Wenzel, R.P. Nosocomial bloodstream infection in critically ill patients. Excess length of stay, extra costs, and attributable mortality. JAMA 1994, 271, 1598–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagon, J.Y.; Chastre, J.; Hance, A.J.; Montravers, P.; Novara, A.; Gibert, C. Nosocomial pneumonia in ventilated patients: A cohort study evaluating attributable mortality and hospital stay. Am. J. Med. 1993, 94, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falagas, M.E.; Snydman, D.R.; George, M.J.; Werner, B.; Ruthazer, R.; Griffith, J.; Rohrer, R.H.; Freeman, R.; Boston Center for Liver Transplantation CMVIG Study Group. Incidence and predictors of Cytomegalovirus pneumonia in orthotopic liver transplant recipients. Transplantation 1996, 61, 1716–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wenzel, R.P. Nosocomial candidemia: Risk factors and attributable mortality. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1995, 20, 1531–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nolla, M.; Chanovas, M.; Torres, J.M.; Nolla, J.; Garcés, J. Cellular Immunity Alterations and Presence of Candida in Patients Admitted to the Intensive Care Unit; Aochi, O., Amaha, K., Takeshita, H., Eds.; Intensive and Critical Care Medicine; International Congress Series 885; Excerpta Medica: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1990; p. 1135. [Google Scholar]

- Ibàñez-Nolla, J.; Torres-Rodríguez, J.M.; Nolla, M.; León, M.A.; Mèndez, R.; Soria, G.; Díaz, R.M.; Marrugat, J. The utility of serology in diagnosing candidosis in non-neutropenic critically ill patients. Mycoses 2001, 44, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibáñez-Nolla, J.; Nolla-Salas, M.; León, M.A.; García, F.; Marrugat, J.; Soria, G.; Díaz, R.M.; Torres-Rodríguez, J.M. Early diagnosis of candidiasis in non-neutropenic critically ill patients. J. Infect. 2004, 48, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León, C.; Ruiz-Santana, S.; Saavedra, P.; Almirante, B.; Nolla-Salas, J.; Álvarez-Lerma, F.; Garnacho-Montero, J.; León, M.A.; EPCAN Study Group. A bedside scoring system (“Candida Score”) for early antifungal treatment in nonneutropenic critically ill patients with Candida colonization. Crit. Care Med. 2006, 34, 730–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittet, D.; Monod, M.; Suter, P.M.; Frenk, E.; Auckenthaler, R. Candida colonization and subsequent infections in critically ill surgical patients. Ann. Surg. 1997, 220, 751–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eggimann, P.; Pittet, D. Candida colonization index and subsequent infection in critically ill surgical patients: 20 years later. Intensive Care Med. 2014, 40, 1429–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, R.L.; Myers, J.P. Nosocomial fungemia in a large community teaching hospital. Arch. Intern. Med. 1987, 147, 2117–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, J.J.; Watanakunakorn, C. Hospital-Acquired fungemia. Its natural course and clinical significance. Am. J. Med. 1979, 67, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komshian, S.V.; Uwaydah, A.K.; Sobel, J.D.; Crane, L.R. Fungemia caused by Candida species and Torulopsis glabrata in the hospitalized patient: Frequency, characteristics, and evaluation of factors influencing outcome. Rev. Infect. Dis. 1989, 11, 379–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calandra, T.; Schneider, R.; Bille, J.; Mosimann, F.; Francioli, P. Clinical significance of Candida isolated from peritoneum in surgical patients. Lancet 1989, 334, 1437–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, P.K.; Tally, F.P.; Kellum, J.; Callow, A.; Gorbach, S.L. Candida infections in surgical patients. Ann. Surg. 1983, 198, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nolla-Salas, J.; Sitges-Serra, A.; León-Gil, C.; Martínez-González, J.; León-Regidor, M.A.; Ibáñez-Lucía, P.; Torres-Rodríguez, J.M. Candidemia in nonneutropenic critically ill patients: Analisys of prognostic factors and assessment of systemic antifungal therapy. Intensive Care Med. 1997, 23, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graninger, W.; Presteril, E.; Schneeweiss, B.; Teleky, B.; Georgopoulos, A. Treatment of Candida albicans fungaemia with fluconazole. J. Infect. Dis. 1993, 26, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aisner, J.; Schimpff, S.C.; Sutherland, J.C.; Young, V.M.; Wiernik, P.H. Torulopsis glabrata infections in patients with cancer: Increasing incidence and relationship to colonization. Am. J. Med. 1976, 61, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryce, E.A.; Roberts, F.J.; Sekhon, A.S.; Coldman, A.J. Yeast in blood cultures. Evaluation of factors influencing outcome. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 1992, 15, 233–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wey, S.B.; Mori, M.; Pfaller, M.A.; Woolson, R.F.; Wenzel, R.P. Hospital-acquired candidemia. The attributable mortality and excess length of stay. Arch. Intern. Med. 1988, 148, 2642–2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bross, J.; Talbot, G.H.; Maislin, G.; Hurwitz, S.; Strom, B.L. Risk factors for nosocomial candidemia. A case-control study in adults without leukemia. Am. J. Med. 1989, 87, 614–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolla-Salas, M.; Monmany, J.; Gich, I.; Ibàñez-Nolla, J. Early Treatment of Candidiasis in Non-Neutropenic Critically Ill Patients. In Proceedings of the World Conference on Magic Bullets: Celebrating Paul Ehrlich’s 150th Birthday, Nürnberg, Germany, 9–11 September 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ergün, M.; Brüggemann, R.J.M.; Alanio, A.; Bentvelsen, R.G.; van Dijk, K.; Ergün, M.; Lagrou, K.; Schouten, J.; Wauters, J.; Lewis White, P.; et al. Classifying patients with invasive fungal disease: Towards a unified case definition? J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2025, 80, 2337–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knaus, W.A.; Wagner, D.P.; Draper, E.A.; Zimmerman, J.E.; Bergner, M.; Bastos, P.G.; Sirio, C.A.; Murphy, D.J.; Lotring, T.; Damiano, A. The APACHE III prognostic system. Risck prediction of hospital mortality for critically ill hospital adults. Chest 1991, 100, 1619–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolla, M. Candida in ICU. 25 Years to Improve Risk Management; Societat Catalana Medicina Intensiva i Crítica; Acadèmia de Ciències Mèdiques de Catalunya i Balears: Barcelona, Spain, 2013; Available online: https://docs.academia.cat/a/47162cb2 (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Vincent, J.L.; Bihari, D.J.; Suter, P.M.; Bruining, H.A.; White, J.; Nicolas-Chanoin, M.H.; Wolff, M.; Spencer, R.C.; Hemmer, M. The prevalence of nosocomial infection in intensive care units in Europe. Results of the European Prevalence of Infection in Intensive Care (EPIC) Study. EPIC International Advisory Committee. JAMA 1995, 274, 639–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eggimann, P.; Garbino, J.; Pittet, D. Epidemiology of Candida species infections in critically ill non-immunosuppressed patients. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2003, 3, 685–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Risk Factors for Candidiasis | Number of Cases (%) |

|---|---|

| Antibiotics | 144 (99) |

| Central venous catheter | 143 (99) |

| Urinary catheter | 140 (97) |

| Antacid therapy | 141 (97) |

| Naso-orogastric catheter | 131 (90) |

| Arterial catheter | 125 (86) |

| Oro-nasotracheal tube and/or tracheostomy | 124 (85) |

| Surgical procedures | 85 (59) |

| Vasoactive drugs | 72 (50) |

| Total parenteral nutrition | 68 (47) |

| Drainages | 65 (45) |

| Blood derivatives | 62 (43) |

| Corticoids | 56 (39) |

| Hemodyalisis | 8 (5) |

| Splenectomy | 5 (3) |

| Causes of Death | Number of Cases (%) |

|---|---|

| Septic shock–Multiple Organ Dysfunction Syndrome | 18 (50) |

| Respiratory failure (hypoxemia) | 8 (22) |

| Brain death | 4 (11) |

| Non-septic shock | 3 (8) |

| Hepatic failure | 3 (8) |

| Location | Positive Cultures Only | Positive Histology Only | Positive Cultures and Histology | All Positive Cultures (n = 24) (%) | All Positive Histology (n = 36) (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lung | 5 | 3 | 3 | 8 (33) | 6 (17) |

| Trachea | 4 | 4 (17) | |||

| Bowel | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 (12) | 2 (6) |

| Heart | 1 | 2 | 1 (4) | 2 (6) | |

| Kidney | 1 | 2 | 1 (4) | 2 (6) | |

| Urinary tract | 3 | 3 (12) | |||

| Liver | 2 | 2 (8) | |||

| Spleen | 2 | 2 (8) | |||

| CNS | 1 | 1 (3) | |||

| Positive samples | 20 | 9 | 4 | 24 | 13 |

| Variables | NAM | AM | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 51 (22) | 69 (14) | 0.001 * |

| Previous illness | 2 (0–4) | 3 (1–4) | 0.009 † |

| Apache III | 72 (24–136) | 90 (58–183) | 0.040 † |

| Abdominal surgery on admission | 24/128 (19) | 9/17 (53) | 0.001 ‡ |

| More than one focus (risk classification) | 100/128 (78) | 17/17 (100) | 0.043 § |

| Candida glabrata at screening | 20/128 (16) | 6/15 (40) | 0.020 ‡ |

| Candida tropicalis at screening | 6/128 (5) | 3/15 (20) | 0.036 § |

| Urine cultures positive at follow-up | 20/128 (16) | 13/75 (75) | <0.001 § |

| Variables | Attributable Mortality | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | p | |

| Abdominal surgery on admission | 9.17 | 1.77–47.39 | 0.008 |

| Appropriate antifungal treatment | <0.01 | <0.01–0.10 | <0.001 |

| Candida glabrata at screening | 7.38 | 1.24–43.98 | 0.028 |

| Previous illness | 1.82 | 0.98–3.37 | 0.055 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ibañez-Nolla, J.; Garcia, F.; Carrasco, M.A.; Nolla-Salas, M. Attributable Mortality to Candidiasis in Non-Neutropenic Critically Ill Patients in the ICU and a Post-Mortem Study. J. Fungi 2025, 11, 871. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof11120871

Ibañez-Nolla J, Garcia F, Carrasco MA, Nolla-Salas M. Attributable Mortality to Candidiasis in Non-Neutropenic Critically Ill Patients in the ICU and a Post-Mortem Study. Journal of Fungi. 2025; 11(12):871. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof11120871

Chicago/Turabian StyleIbañez-Nolla, Jordi, Felip Garcia, Miquel A. Carrasco, and Miquel Nolla-Salas. 2025. "Attributable Mortality to Candidiasis in Non-Neutropenic Critically Ill Patients in the ICU and a Post-Mortem Study" Journal of Fungi 11, no. 12: 871. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof11120871

APA StyleIbañez-Nolla, J., Garcia, F., Carrasco, M. A., & Nolla-Salas, M. (2025). Attributable Mortality to Candidiasis in Non-Neutropenic Critically Ill Patients in the ICU and a Post-Mortem Study. Journal of Fungi, 11(12), 871. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof11120871