Oral Health Assessment for Older Residents in Long-Term Care Facilities Using Video Recording by a Mobile Electronic Device

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measurements

2.3. Outcomes

2.4. Other Variables

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Participants

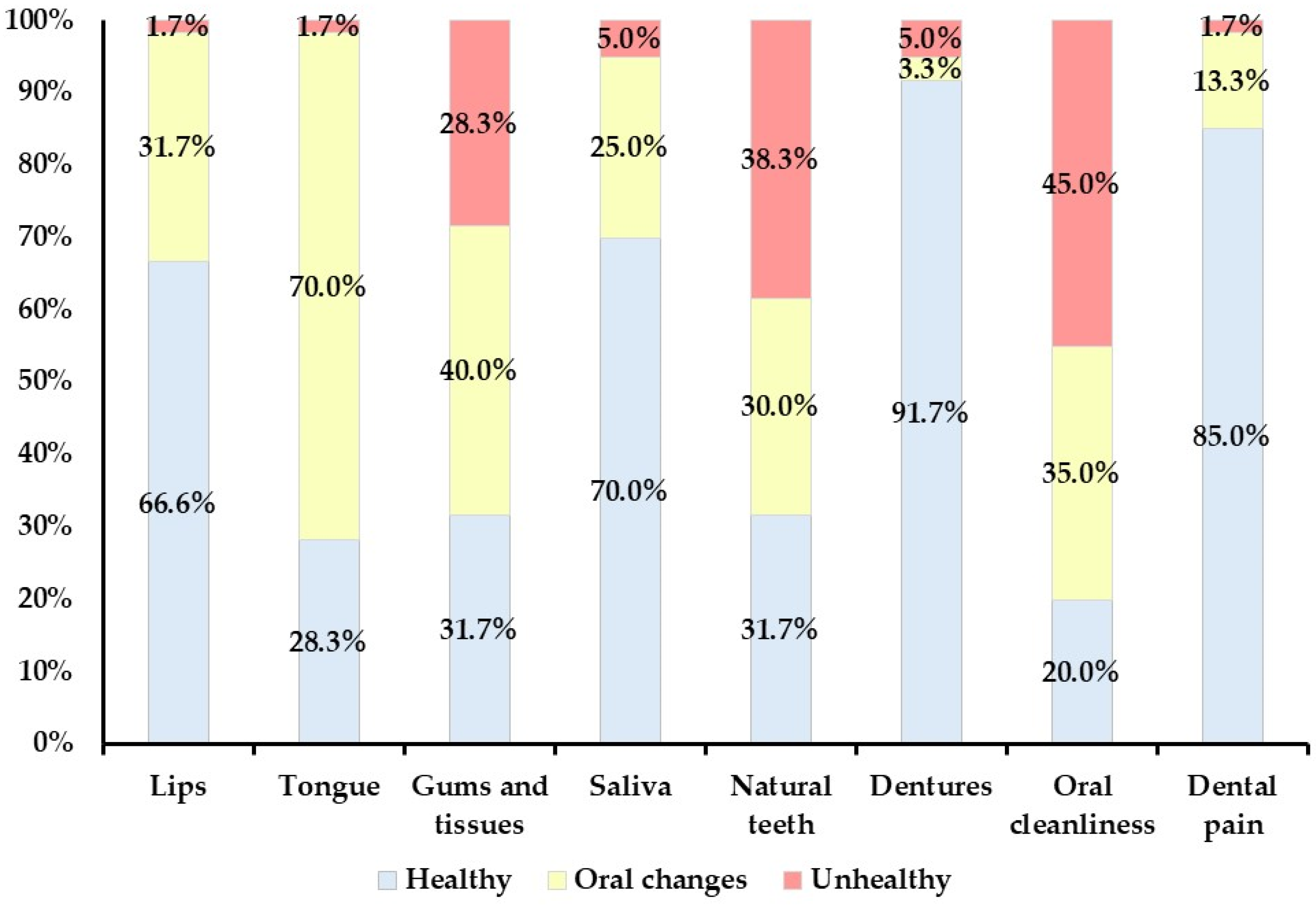

3.2. Oral Health Status Assessment at the Facilities and via Intraoral Video Recording

3.3. Reliability of Oral Health Status Assessment Using Intraoral Video Recordings

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xue, Q.L.; Bandeen-Roche, K.; Varadhan, R.; Zhou, J.; Fried, L.P. Initial manifestations of frailty criteria and the development of frailty phenotype in the Women’s Health and Aging Study II. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2008, 63, 984–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koller, D.; Schön, G.; Schäfer, I.; Glaeske, G.; van den Bussche, H.; Hansen, H. Multimorbidity and long-term care dependency—A five-year follow-up. BMC Geriatr. 2014, 14, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishino, T. Quantitative properties of the macro supply and demand structure for care facilities for elderly in Japan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, K.; Tominaga, T.; Kikutani, T.; Sakuda, T.; Tomida, H.; Tanaka, Y.; Mizukoshi, A.; Ichikawa, Y.; Ozeki, M.; Takahashi, N.; et al. Oral status of older adults receiving home medical care: A cross-sectional study. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2024, 24, 706–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.-H.; Han, H.-R.; Oh, B.-M.; Lee, J.; Park, J.-A.; Yu, S.J.; Chang, H. Prevalence and associated factors of dysphagia in nursing home residents. Geriatr. Nurs. 2013, 34, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, M.N.; Ickert, C.; Slaughter, S.E.; Lengyel, C.; Carrier, N.; Keller, H. Oral Health status of long-term care residents in Canada: Results of a national cross-sectional study. Gerodontology 2018, 35, 359–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerritsen, P.; Cune, M.; van der Bilt, A.; Abbink, J.; de Putter, C. Effects of integrated dental care on oral treatment needs in residents of nursing homes older than 70 years. Spec. Care Dent. 2015, 35, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Guo, Y.; Hu, Z.; Zhou, F.; Li, S.; Xu, H. Association of oral status with frailty among older adults in nursing homes: A cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuyama, Y.; Komiyama, T.; Ohi, T.; Hattori, Y. Association between oral health and nutritional status among older patients requiring long-term care who received home-visit dental care. J. Oral Sci. 2024, 66, 130–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewake, N.; Hashimoto, H.; Nonoyama, T.; Nonoyama, K.; Shimazaki, Y. Posterior occluding pairs of teeth or dentures and 1-year mortality in nursing home residents in Japan. J. Oral Rehabil. 2020, 47, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaven, A.; Marshman, Z. Barriers and facilitators to accessing oral healthcare for older people in the UK: A scoping review. Br. Dent. J. 2024; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komulainen, K.; Ylöstalo, P.; Syrjälä, A.; Ruoppi, P.; Knuuttila, M.; Sulkava, R.; Hartikainen, S. Preference for dentist’s home visits among older people. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2012, 40, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, K.; Kikutani, T.; Takahashi, N.; Tohara, T.; Furuya, H.; Ichikawa, Y.; Komagata, Y.; Mizukoshi, A.; Ozeki, M.; Tamura, F.; et al. A prospective cohort study on factors related to dental care and continuation of care for older adults receiving home medical care. Odontology, 2024; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, Y.; Okada, A.; Kakuta, E.; Otsuka, R.; Saito, H.; Maekawa, H.; Daikoku, H.; Hanada, N.; Sato, T. Workforce and contents of home dental care in Japanese insurance system. Int. J. Dent. 2020, 2020, 7316796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, S.C.; Thomas, C.; Yonezawa, Y.; Hojo, Y.; Nakamura, T.; Kobayashi, K.; Sato, H.; Da Silva, J.D.; Kobayashi, T.; Ishikawa-Nagai, S. Comprehensive assessment of the universal healthcare system in dentistry Japan: A retrospective observational study. Healthcare 2022, 10, 2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czwikla, J.; Rothgang, H.; Schwendicke, F.; Hoffmann, F. Dental care utilization among home care recipients, nursing home residents, and older adults not in need of long-term care: An observational study based on German insurance claims data. J. Dent. 2023, 136, 104627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanagihara, Y.; Suzuki, H.; Furuya, J.; Nakagawa, K.; Yoshimi, K.; Seto, S.; Shimizu, K.; Tohara, H.; Minakuchi, S. Usefulness of oral health assessment performed by multiple professionals using a short video recording acquired with a tablet device. J. Dent. Sci. 2024, 19, 1699–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmers, J.M.; King, P.L.; Spencer, A.J.; Wright, F.A.; Carter, K.D. The oral health assessment tool—Validity and reliability. Aust. Dent. J. 2005, 50, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlson, M.E.; Pompei, P.; Ales, K.L.; MacKenzie, C.R. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J. Chronic Dis. 1987, 40, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennett, B.; Teasdale, G. Aspects of coma after severe head injury. Lancet 1977, 1, 878–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konishi, T.; Inokuchi, H.; Yasunaga, H. Services in public long-term care insurance in Japan. Ann. Clin. Epidemiol. 2023, 6, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, H.; Furuya, J.; Nakagawa, K.; Hidaka, R.; Nakane, A.; Yoshimi, K.; Shimizu, Y.; Saito, K.; Itsui, Y.; Tohara, H.; et al. Factors influencing the selection of oral healthcare providers in multidisciplinary Nutrition Support Team for malnourished inpatients: A cross-sectional study. J. Oral Rehabil. 2023, 50, 1446–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleiel, D.; Rott, T.; Scharfenberg, I.; Wicht, M.J.; Barbe, A.G. Use of smartphone photos to document the oral care status of nursing home residents. Gerodontology 2023, 40, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queyroux, A.; Saricassapian, B.; Herzog, D.; Müller, K.; Herafa, I.; Ducoux, D.; Marin, B.; Dantoine, T.; Preux, P.-M.; Tchalla, A. Accuracy of teledentistry for diagnosing dental pathology using direct examination as a gold standard: Results of the Tel-e-dent study of older adults living in nursing homes. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2017, 18, 528–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.C.; Chang, Y.C. A bibliometric analysis of teledentistry published in the category of dentistry, oral surgery and medicine. J. Dent. Sci. 2024, 19, 1827–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Liu, J.; Zhou, L.; Tian, J.; Chen, X.; Zhang, W.; Wang, H.; Zhou, W.; Gao, Y. Usability evaluation of mHealth apps for elderly individuals: A scoping review. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2022, 22, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, R.C.W.; Thu, K.M.; Chaurasia, A.; Hsung, R.T.C.; Lam, W.Y. A systematic review of the use of mHealth in oral health education among older adults. Dent. J. 2023, 11, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, B.B.; Perdoncini, N.N.; da Silva, V.C.; Gueiros, L.A.M.; Carrard, V.C.; Lemos, C.A.; Schussel, J.L.; Amenábar, J.M.; Torres-Pereira, C.C. Telediagnosis of oral lesions using smartphone photography. Oral Dis. 2022, 28, 1573–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, P.; Jasrasaria, N.; Bains, R.; Singh, A.; Manar, M.; Kumar, A. The efficacy of dental caries telediagnosis using smartphone: A diagnostic study in geriatric patients. Cureus 2023, 15, e33256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I. Digital dental photography. part 5: Lighting. Br. Dent. J. 2009, 207, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapp, L.; Sourdet, S.; Vellas, B.; Lacoste-Ferré, M.H. Oral Health and the frail elderly. J. Frailty Aging 2017, 6, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmers, J.M. Behavior management and communication strategies for dental professionals when caring for patients with dementia. Spec. Care Dent. 2000, 20, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmers, J.; Pearson, A. Oral hygiene care for residents with dementia: A literature review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2005, 52, 410–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishimaru, M.; Ono, S.; Morita, K.; Matsui, H.; Yasunaga, H. Domiciliary dental care among homebound older adults: A nested case-control study in Japan. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2019, 19, 679–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mean ± SD | Median | n | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 86.1 ± 7.65 | 88 | 60 | ||

| Sex | Male | 18 | 30.0 | ||

| Female | 42 | 70.0 | |||

| Systemic disorder | Dementia | 42 | 70.0 | ||

| High blood pressure | 21 | 35.0 | |||

| Cerebrovascular disease | 21 | 35.0 | |||

| Bone fracture | 11 | 18.3 | |||

| Disuse syndrome | 10 | 16.7 | |||

| Heart disease | 9 | 15.0 | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 9 | 15.0 | |||

| Parkinson’s disease | 7 | 11.7 | |||

| Aspiration pneumonia | 5 | 8.3 | |||

| Others | 5 | 8.3 | |||

| CCI | 2.3 ± 1.25 | 2.0 | |||

| GCS | 12.9 ± 2.61 | 14.0 | |||

| Communication ability | 0 | 30 | 50.0 | ||

| 1 | 19 | 31.7 | |||

| 2 | 11 | 18.3 | |||

| ADLs | 0 | 10 | 16.7 | ||

| 1 | 26 | 43.3 | |||

| 2 | 24 | 40.0 | |||

| Level of care needed | 1 | 3 | 5.0 | ||

| 2 | 6 | 10.0 | |||

| 3 | 15 | 25.0 | |||

| 4 | 15 | 25.0 | |||

| 5 | 21 | 35.0 |

| Category | B | V1 | V2 | V3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | |

| Median | Median | Median | Median | |

| Lips | 0.4 ± 0.5 | 0.4 ± 0.5 | 0.4 ± 0.6 | 0.3 ± 0.5 |

| 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| Tongue | 0.7 ± 0.5 | 0.7 ± 0.5 | 0.7 ± 0.4 | 0.7 ± 0.5 |

| 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Gums and tissues | 1.0 ± 0.8 | 0.8 ± 0.8 | 1.0 ± 0.7 | 0.8 ± 0.8 |

| 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Saliva | 0.4 ± 0.6 | 0.4 ± 0.6 | 0.5 ± 0.5 | 0.3 ± 0.5 |

| 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| Natural teeth | 1.1 ± 0.8 | 1.0 ± 0.8 | 1.2 ± 0.8 | 1.0 ± 0.8 |

| 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Dentures | 0.1 ± 0.5 | 0.1 ± 0.4 | 0.1 ± 0.5 | 0.2 ± 1.1 |

| 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| Oral cleanliness | 1.3 ± 0.8 | 1.3 ± 0.8 | 1.2 ± 0.7 | 1.2 ± 0.8 |

| 1.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 1.5 | |

| Dental pain | 0.2 ± 0.4 | 0.2 ± 0.4 | 0.1 ± 0.3 | 0.2 ± 0.4 |

| 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| Total score | 5.0 ± 2.3 | 5.0 ± 2.5 | 5.3 ± 2.1 | 4.8 ± 2.3 |

| 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.5 | 5.0 |

| Category | B-V1 | B-V2 | B-V3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent Agreement | Weighted Kappa Coefficients (95% CI) | Percent Agreement | Weighted Kappa Coefficients (95% CI) | Percent Agreement | Weighted Kappa Coefficients (95% CI) | |

| Lips | 88 | 0.787 * (0.626–0.947) | 87 | 0.768 * (0.612–0.924) | 95 | 0.903 * (0.792–1.015) |

| Tongue | 90 | 0.782 * (0.610–0.954) | 87 | 0.686 * (0.492–0.880) | 98 | 0.964 * (0.894–1.034) |

| Gums and tissues | 78 | 0.793 * (0.665–0.921) | 75 | 0.769 * (0.655–0.882) | 73 | 0.751 * (0.617–0.885) |

| Saliva | 85 | 0.773 * (0.624–0.922) | 77 | 0.629 * (0.449–0.808) | 77 | 0.572 * (0.396–0.748) |

| Natural teeth | 85 | 0.891 * (0.821–0.961) | 75 | 0.816 * (0.726–0.906) | 80 | 0.857 * (0.777–0.936) |

| Dentures | 95 | 0.754 * (0.429–1.079) | 95 | 0.881 * (0.714–1.047) | 95 | 0.918 * (0.785–1.051) |

| Oral cleanliness | 85 | 0.873 * (0.787–0.959) | 85 | 0.864 * (0.776–0.952) | 75 | 0.808 * (0.708–0.907) |

| Dental pain | 97 | 0.903 * (0.760–1.046) | 93 | 0.769 * (0.583–0.956) | 95 | 0.850 * (0.662–1.038) |

| Intraclass correlation coefficients (1.1) (95% CI) | Intraclass correlation coefficients (2.1) (95% CI) | Intraclass correlation coefficients (2.1) (95% CI) | ||||

| Total score | 0.931 ** (0.888–0.958) | 0.889 ** (0.819–0.932) | 0.788 ** (0.669–0.867) | |||

| Category | OHAT V2–V3 | |

|---|---|---|

| Percent Agreement | Weighted Kappa Coefficients (95% CI) | |

| Lips | 85 | 0.738 * (0.571–0.905) |

| Tongue | 88 | 0.730 * (0.550–0.910) |

| Gums and tissues | 63 | 0.681 * (0.554–0.808) |

| Saliva | 73 | 0.494 * (0.296–0.692) |

| Natural teeth | 72 | 0.720 * (0.572–0.868) |

| Dentures | 98 | 0.687 * (0.228–1.145) |

| Oral cleanliness | 70 | 0.755 * (0.642–0.868) |

| Dental pain | 92 | 0.699 * (0.480–0.918) |

| Intraclass correlation coefficient (2.1) (95% CI) | ||

| Total score | 0.750 ** (0.610–0.844) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ako, K.; Suzuki, H.; Watanabe, M.; Suzuki, H.; Namikawa, K.; Hirayama, M.; Yamane, K.; Mukai, T.; Hatanaka, Y.; Furuya, J. Oral Health Assessment for Older Residents in Long-Term Care Facilities Using Video Recording by a Mobile Electronic Device. Geriatrics 2024, 9, 135. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics9050135

Ako K, Suzuki H, Watanabe M, Suzuki H, Namikawa K, Hirayama M, Yamane K, Mukai T, Hatanaka Y, Furuya J. Oral Health Assessment for Older Residents in Long-Term Care Facilities Using Video Recording by a Mobile Electronic Device. Geriatrics. 2024; 9(5):135. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics9050135

Chicago/Turabian StyleAko, Kazuki, Hiroyuki Suzuki, Masataka Watanabe, Hosei Suzuki, Kae Namikawa, Mana Hirayama, Kunihito Yamane, Tomoko Mukai, Yukiko Hatanaka, and Junichi Furuya. 2024. "Oral Health Assessment for Older Residents in Long-Term Care Facilities Using Video Recording by a Mobile Electronic Device" Geriatrics 9, no. 5: 135. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics9050135

APA StyleAko, K., Suzuki, H., Watanabe, M., Suzuki, H., Namikawa, K., Hirayama, M., Yamane, K., Mukai, T., Hatanaka, Y., & Furuya, J. (2024). Oral Health Assessment for Older Residents in Long-Term Care Facilities Using Video Recording by a Mobile Electronic Device. Geriatrics, 9(5), 135. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics9050135