Abstract

Ikigai—a Japanese concept that includes elements such as life’s purpose and meaning—has been reported to be associated with various systemic health conditions, such as the risk of developing physical dysfunction or death in older adults. However, there are no reports that comprehensively examine the psychological and social aspects of Ikigai. We attempted to clarify the characteristics of Ikigai by examining it from a biopsychosocial model using physical, psychological, and social perspectives through a cross-sectional study on sarcopenia, frailty and healthy life expectancy in a hilly and mountainous area of Japan. Koyadaira in Mima City, which is located in a hilly and mountainous region on Shikoku Island in Japan, was targeted. This cross-sectional study included 105 outpatients aged 65 and over, with an average age of 79.02 ± 6.91 years. Ikigai (self-rating score on a scale of 0 (no Ikigai) to 5 (the highest Ikigai)) participants’ level of physical activity (the Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly, PASE), degree of depression (the Geriatric Depression-15 Scale, GDS-15), cognitive function (the Mini-Mental State Examination, MMSE) and social isolation (the abbreviated Lubben Social Network Scale, LSNS-6) was assessed. Significant positive correlations were found between PASE and MMSE. The LSNS-6 significantly correlated with the MMSE and GDS-15. In a path model, out of four paths from PASE, GDS-15, MMSE, and LSNS-6 to Ikigai, the path from the GDS-15 alone was significant (correlation coefficient −0.271, p < 0.01). The adaptability of this model was good. This study indicates that depressive status has a large impact on Ikigai, along with physical, cognitive, and social conditions; thus, it is appropriate to consider that an affective psychological status, such as depressive symptoms, is a fundamental condition for having Ikigai.

1. Introduction

The global older adult population has increased in the recent past. According to the World Population Prospects report (2019) [1], the aging rate, which was around 9.1% in 2019, is expected to reach 11.7% in 2030 and 15.9% in 2050. Population aging is a crucial issue in most developed countries. Many countries have been working on extending healthy life expectancy through various measures ever since the World Health Organization (WHO) proposed the index of healthy life expectancy in 2000 [2]. In particular, Japan’s aging rate was 29.1% as of 2022, the world’s highest, after surpassing Italy in 2005, and Japan’s policies to extend healthy life expectancy and countermeasures for older adults are attracting attention.

Psychological factors play an important role in morbidity risk and mortality, and are also an important factor for comprehending the quality of life (QoL) and well-being of the older adults [3,4,5]. One psychological factor is Ikigai, a concept that includes elements such as life’s purpose and meaning. It has been used in Japan to describe that which gives an individual value in one’s life and makes it worthwhile, and the concept has been widely quoted all over the world [6,7,8,9]. The Oxford Encyclopedia [10] defines it as “a motivating force; something or someone that gives a person a sense of purpose or a reason for living”. More recently, García and Miralles defined Ikigai as an overlap of four factors: what you love (passion), what you are good at (profession), what you can be paid for (vocation), and what the world needs (mission) [11].

However, the original Japanese connotation is not necessarily as described above, and the four factors are not always equally important. From the Japanese viewpoint, Naoi states that Ikigai is divided into its target and mental state for the target, and two factors, foundational state and performance goal, are needed to have Ikigai [12]. Additionally, Namihira reported that Ikigai must be considered based on the three concepts: to share Ikigai, to have a more concrete target of Ikigai, and to be significant through the ages [13].

Having Ikigai has been reported to be associated with various systemic health conditions in older adults. A 7-year prospective cohort study by Sone et al. reported that the risk of death in those who did not have Ikigai increased compared to those who had Ikigai [14]. Mori et al. reported that having Ikigai significantly reduces the risk of developing physical dysfunction in the future [15]. However, there are no reports that comprehensively examine the psychological and social aspects of Ikigai in addition to its physical aspects. The WHO Charter defines health as “a state of complete physical, mental, spiritual, and social well-being, not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” [16]. Engel also presents the biopsychosocial model, in which health is understood and addressed within biopsychosocial systems [17]. In the medical field, there is a shift from the conventional reductionistic biomedical model to the biopsychosocial model in understanding and treating clinical conditions. In other words, patients are now being evaluated holistically, with an emphasis on the relationship between biological, psychological, and social factors and the degree of their influence on the patient’s condition. This approach is extremely useful for evaluating Ikigai, which is thought to be based on the interconnectedness of physical, psychological, and social factors, and leads to a comprehensive assessment of Ikigai.

Based on the aforementioned Japanese way of perceiving Ikigai, it is hypothesized that the Ikigai of older adults is affected by the perspective of a holistic individual, that is, their physical, psychological, and social conditions. Focusing on older adults living in hilly and mountainous regions with a particularly high aging rate in Japan, we comprehensively examined the physical, psychological, including affective and cognitive aspects, and social aspects of Ikigai, and attempted to clarify the biopsychosocial characteristics of Ikigai in a cross-sectional study.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Participants

An ongoing cohort study is currently investigating the relationship between healthy life expectancy and oral, cognitive, and physical functions; social factors such as participation in community activities; and nutritional intake among older adults in hilly and mountainous regions in Japan, titled “A Population-Based Prospective Study on the Roles of Shopping, Oral Function, Nutrition, and Genetics in Sarcopenia, Frailty and Healthy Life Expectancy in Mima City” (The Mima-SONGS Study). This study commenced in 2018 with the aim of developing comprehensive efforts to extend the healthy life expectancy of older adults. The target area was Koyadaira in Mima City, located in the western part of Tokushima Prefecture (on Shikoku Island to the west of Osaka) in Japan, and approximately 95% of this area is mountainous. In 2018, Koyadaira’s population was 645 and its aging rate was 60%; thus, it is said that Koyadaira is highly likely to disappear in the near future. This cross-sectional study included 105 outpatients aged 65 and over, with an average age of 79.02 ± 6.91 years, who regularly visit the Mima Municipal Koyadaira Clinic, the medical institution in the area. All participants provided written informed consent prior to study participation. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kyoto Medical Center (approval number: 17-032). It was conducted according to the criteria set out by the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants gave written informed consent before taking part in the study.

2.2. Measurements

Ikigai was assessed through the participants’ response to the question, “Do you have any pleasure or Ikigai?” on the basis of previous report [18]. As an operational definition, this subjective score of 0 indicated having no Ikigai and 5 indicated having higher Ikigai. The participants were asked to rate self-rated Ikigai on this scale of 0 to 5, with higher scores representing higher Ikigai.

Regarding the physical aspect, the participants’ level of physical activity was assessed using the Japanese version of the Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE). The PASE, originally developed by Washburn et al. [19], has been internationally and widely used to assess physical activity in older adults [20,21]. The PASE score includes information on leisure, household, and occupational activities, and is calculated by the amount of time spent (hours/week) on or participation (yes/no) in the said activity over a 1-week period. The reliability of the Japanese version of the PASE was confirmed by Hagiwara et al. [22], with an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.65. In this study, the total physical activity score, ranging from 0 to 360 points and including scores for leisure, household, and occupational activities, was calculated as the total PASE score.

For the affective psychological assessment, the degree of depression was evaluated using the Japanese short version of the Geriatric Depression-15 Scale (GDS-15) for older adults, developed by Sheikh and Yesavage [23]. The GDS, originally developed by Yesavage et al. [24], contains 30 items and is one of the most widespread and reliable screening scales to evaluate depression among older adults [25,26]. Each item is scored dichotomously (yes/no). The total score ranges from 0 to 15 points, with higher scores representing more depressive symptoms. The reliability of the Japanese version of the GDS-15 was confirmed by Sugishita et al. [27], with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.83.

For the cognitive psychological assessment, cognitive function was assessed using the Japanese version of the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE). The original version of the MMSE is the best-known and most commonly used scale for cognitive function evaluation [28]. The reliability of the Japanese version of the MMSE was confirmed by Sugishita et al. [29], with a test–retest reliability of 0.80. The total score ranges from 0 to 30 points, with higher scores indicating better cognitive functioning.

For social assessment, social isolation was assessed using the Japanese version of the abbreviated Lubben Social Network Scale (LSNS-6), reported by Lubben [30]. The LSNS-6 has been used worldwide as a tool to screen for social isolation in older adults [31], and the reliability of the Japanese version of the LSNS-6 was confirmed by Kurimoto et al. [32], with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.82. In the LSNS-6, the total score ranges from 0 to 30 points, with a low score indicating weaker social networks and social isolation. Taking into consideration the characteristics of older people, the examiners read the questions aloud using a printed questionnaire form and evaluated if the subjects could visually confirm the answers on it. The examiners then filled in the responses from the subjects on the form. Additionally, each participant’s age and gender were recorded as demographic attributes.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

A one-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni post hoc tests was used for the PASE, MMSE, GDS-15, and LSNS-6 for a comparison in each Ikigai group. Spearman’s correlation was used to examine the relationship between PASE, MMSE, GDS-15, and LSNS-6.

Multiple regression analysis with the Ikigai score as the dependent variable was conducted to examine the age and gender adjusted effects of PASE, MMSE, GDS-15, and LSNS-6 on Ikigai.

A path model analysis was then conducted to examine a hypothesis model of the effect of physical, psychological, and social factors on Ikigai based on the obtained results using a covariance structure analysis. p value, goodness-of-fit index (GFI), adjusted goodness-of-fit index (AGFI), comparative fit index (CFI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) were calculated to examine the model’s adaptability. A p value of >0.05, and scores of >0.95, >0.90, >0.97, and <0.08 for GFI, AGFI, CFI, and RMSEA, respectively, were considered to indicate a good model fit [33].

The statistical power of the regression-based path analysis was calculated using G*Power 3.1.9.6 with an effect size of 0.15, an alpha of 0.05, 105 participants, and 4 predictors. The results indicated that the statistical power was high at 0.98. All statistical analyses were conducted with a significance level of 0.05 using SPSS 25.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA) and Amos (SPSS Statistics 25.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) software packages.

3. Results

Table 1 presents the means and standard deviations for the measured variable in this study. There were 35 male participants (33.3%) and 70 female participants (66.7%) with an age range of 65 to 94 years and a mean age of 79.0 years. The average value of each measured variable was 3.6 for Ikigai, 115.2 for the PASE, 26.6 for the MMSE, 3.4 for the GDS-15, and 22.9 for the LSNS-6.

Table 1.

Participants’ characteristics.

Table 2 shows the means and standard deviations of the Ikigai score for the physical, psychological, and social assessments. The groups with 0 and 1 for the Ikigai score were excluded from the statistical analysis, as they comprised only one or two subjects, respectively.

Table 2.

Means and standard deviations of the Ikigai score in age, gender and four assessments: PASE, MMSE, GDS-15, and LSNS-6.

Regarding age, gender and PASE, no characteristic trends were observed in each group. It was observed that the group with the Ikigai score of 2 exhibited lower values than the group with the Ikigai score of 3 or higher for the MMSE and LSNS-6. A trend toward lower GDS-15 values was observed as the Ikigai score increased above 2. The GDS-15 values of the groups with Ikigai scores of 4 and 5 were significantly lower than those of the group with a score of 2 (p = 0.045 and p = 0.016, respectively).

Table 3 shows the results of the correlation analysis and Spearman’s correlation coefficients (SCC) among the variables. Significant positive correlations were found between PASE and MMSE (SCC: 0.227). The LSNS-6 significantly correlated with both the MMSE (SCC: 0.325) and the GDS-15 (SCC: −0.361).

Table 3.

Spearman’s correlation coefficients for the four assessments: PASE, MMSE, GDS-15, and LSNS-6.

Table 4 shows the results of the multiple regression analysis after age and gender adjustment. A significant association was found only for GDS-15 (β: −0.407, p < 0.01). No multicollinearity was noted among the independent variables, and the variance inflation factor (VIF) values ranged between 1.282 and 1.605.

Table 4.

Summary statistics of multiple regression analysis after age and gender adjustment for Ikigai and the four assessments: PASE, MMSE, GDS-15, and LSNS-6.

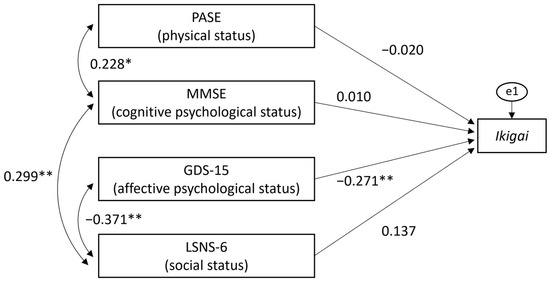

Considering the above results, a covariance structure analysis was performed to investigate a path model in which physical, psychological, and social assessments affect Ikigai, as shown in Figure 1. In this model, four paths from physical, psychological, and social assessments to Ikigai and correlations between the PASE and MMSE, the LSNS-6 and GDS-15, and the LSNS-6 and MMSE were confirmed. The path coefficients from the PASE, MMSE, GDS-15, and LSNS-6 to Ikigai were as follows, respectively: −0.020, 0.010, −0.271, and 0.137. The path from the GDS-15 to Ikigai was significant (p < 0.01). The adaptability of this model was good (p = 0.133, GFI: 0.979, AGFI: 0.895, CFI: 0.944, RMSEA: 0.091).

Figure 1.

Covariance structure model examining the relationship between Ikigai and physical/psychological/social factors. (PASE: Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly, MMSE: Mini-Mental State Examination, GDS-15: Geriatric Depression-15 Scale, LSNS-6: Lubben Social Network Scale). Statistical significance (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01).

4. Discussion

Ikigai, in which the concept with a spiritual approach originated in Japan, has been described in various terms [11]. In this study, Ikigai was investigated with three aspects: physical, psychological (including affective and cognitive aspects), and social factors, in line with the definition of frailty and health, using objective assessment scales.

There have been various reports on the relationship between Ikigai or “having a purpose in life” and physical factors. Alimujiang reported that having a life purpose promotes healthy behaviors [34], and McKnight and Kashdan stated that it triggers one’s engagement in healthy behaviors, such as exercise, which affects one’s physical condition [35]. Boyle et al. also reported that having a life purpose can reduce the risk in the future activities and the instrumental activities of daily living [36]. The correlation between Ikigai and depression as an affective psychological factor has been studied in several earlier studies. Wilkes et al. reported a significant negative correlation between them [37]. Nakao et al. [38] also reported a significant negative correlation between Ikigai and the GDS-15, which was used in this study as a measure of affective psychological state. Therefore, Ikigai has been described as a factor for a better life and has been reported to have a positive impact on the maintenance of physical and affective psychological conditions.

This study indicates that affective psychological status, such as depression, has a large impact on Ikigai along with physical, cognitive psychological, and social conditions. Thus, it is appropriate to consider that good affective psychological status is a fundamental condition for having Ikigai. As García and Miralles suggested, Ikigai is a fundamental state—and especially a fundamental psychological condition—after which one works with the goals of “passion”, “profession”, “vocation”, and “mission”, which can positively impact one’s physical, psychological and social conditions [11]. The former is a “foundational state” and the latter are “target states” according to the opinions of Japanese researchers. The concept of “meaning of life”, which is one of the elements of Ikigai, is thought to include three components: cognitive, affective, and motivational [39]. The emotional component includes satisfaction, fulfillment, and happiness, all of which are listed as the mental states that comprise Ikigai [12]. The GDS-15, an affective psychological status assessment tool used in this study, includes questions such as “Are you basically satisfied with your life? (satisfaction)”, “Do you feel that your life is empty? (fulfillment)”, and “Do you think it is wonderful to be alive now? (happiness).” The results of this study are also understandable, as affective psychological status forms the basis for obtaining Ikigai.

As mentioned above, past studies have reported that a significant relationship exists between one’s physical condition, such as healthy behaviors and activities of daily living, and Ikigai. However, no significant relationship between PASE as a physical condition and Ikigai was observed. To date, there is little information available on the relationship between PASE and Ikigai. The average value of PASE and the age of the participants in this study were 115.2 and 79.0, respectively. In a past study with community-dwelling older adults in Japan [22], these values were 114.9 and 72.6, respectively. Although the average age in our study was slightly higher compared to the past study, the PASE was similar in these two studies. Considering these facts, regarding the relationship between PASE and Ikigai in our study, these results may reflect the unique characteristics in hilly and mountainous regions, where citizens support each other, interact with others, discover hobbies or life purposes, and find Ikigai, even if physical activity is low. As for the relationship between MMSE, which indicates cognitive function, and Ikigai, the results of this study showed no significant relationship between them. Several significant associations between cognitive function and Ikigai have been reported. Okuzono et al. [6] reported that having Ikigai reduced the risk of developing dementia three years later by 0.64-fold. Considering that the median MMSE value of the subjects in this study was 27 and the percentage of subjects with severe cognitive decline with the value of 20 or less was 6.7%, which were comparable to previous studies in Japan [40,41], it is possible to obtain Ikigai even with cognitive decline, as in the PASE described above. The results may reflect a unique characteristic of hilly and mountainous areas in Japan, where it is possible to have Ikigai despite cognitive decline, as in the PASE study. There is also a report [42] that found no significant relationship between psychological well-being and MMSE in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Further research is needed to investigate the relationship between physical function, cognitive function, and Ikigai, including the characteristics of the older subjects. Significantly, we found that affective psychological conditions, such as depression, have large impact on Ikigai in this setting.

Similar to the relationship with physical factors, the relationship between Ikigai and social factors has been examined. Seko and Hirano reported that people who were more engaged in social activities, such as interacting with neighbors, have higher Ikigai [43]. In particular, older women are more likely to participate in community activities and have a higher subjective sense of health [44]. In this study, a trend toward higher LSNS-6 values was observed as the Ikigai score increased, but the difference was not statistically significant. Moreover, no significant association was found between the LSNS-6 results and Ikigai with a multiple regression analysis and covariance structure analysis. With respect to the LSNS-6’s cut-off value, a person with a score of 11 or less is considered at risk for social isolation [32]; however, based on this cut-off value, no participants in this study were at risk of social isolation. Thus, it is thought that the non-social isolation tendency of the study participants affected these results.

Regarding the limitations of this study, the participants were a unique group of older adults living in the hilly and mountainous regions in Japan. Compared to urban and rural areas, there are many restrictions to daily life in this area, such as mobility and shopping; and the social situation does not always change throughout one’s lifetime because work life and daily life are comparatively one entity. This study did not examine the effects of confounding factors, such as vision and hearing disorders and educational background, which are thought to influence Ikigai, in addition to these regional characteristics. This is one of the limitations of this study and should be examined in the future. However, considering that hilly and mountainous areas account for 70% of Japan’s land area and have a high aging rate, it is important to examine Ikigai-related factors in older adults living in these areas. This study’s findings will be more meaningful if compared with results of future studies on older adults living in urban or rural areas. Furthermore, the differences in the number of participants in each Ikigai group may have resulted in a sampling bias. Although this study’s target area is a hilly and mountainous region, with limited living resources for daily life, 97.1% of the total population had moderate or high Ikigai (Ikigai score of 2–5), and only 2.9% of the participants had low Ikigai (Ikigai score of 0 or 1). Therefore, most participants in the present study had high levels of Ikigai; the results should be carefully interpreted.

Another limitation is regarding the assessment of Ikigai. In this study, physical, psychological, and social factors were assessed using the PASE, GDS-15, MMSE, and LSNS-6, which already have high validity and reliability. In this study, Ikigai was assessed through the self-rated score on a scale of 0 to 5. Although the question item on Ikigai was set based on the previous report [18], the reliability and validity of this method have not been examined. Ikigai is the integration of the object of Ikigai and the feelings associated with its object, which is difficult to assess because it has spiritual aspects in addition to elements such as the will to live, a sense of being, dreams, and a sense of fulfillment in life. Regarding the assessment of Ikigai, the Ikigai-9 was developed by Imai et al. for middle-aged and older adults in a specific region [45]. To date, there is no assessment that can be used globally and across generations, from adolescence to older age. As Ikigai is subjective, the visual analog scale may be preferable. The development of an assessment questionnaire for Ikigai with proven reliability and validity is needed for future studies. As mentioned above, Ikigai is associated with a variety of general health conditions, including mortality and physical dysfunction. In the present study, when examining Ikigai from a biopsychosocial perspective, an affective psychological status, such as depressive symptoms, was found to have the greatest impact on Ikigai. In other words, improving one’s affective psychological status as a prerequisite for achieving Ikigai may contribute to extending one’s healthy life expectancy. Conceivably, this study was conducted in one hilly and mountainous area, and the results were obtained from a limited area. However, this study is the first to identify the Ikigai of older people in such an area. Additionally, considering that hilly and mountainous areas have an extremely high aging rate, and that the aging of the population is expected to continue worldwide, we believe that the results of this study obtained from this region are highly significant.

5. Conclusions

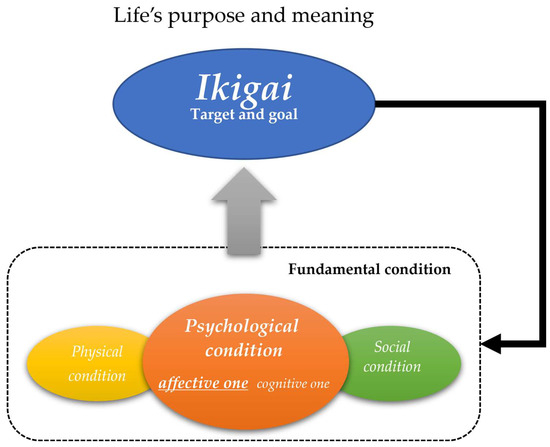

Ikigai, which is an original Japan concept and is associated with the QoL and well-being of older adults, was analyzed through the cross-sectional study. Thus, we propose a biopsychosocial model of Ikigai, which indicates that depressive statuses have a large impact on Ikigai, along with physical, cognitive, and social conditions (Figure 2). It is appropriate to consider that an affective psychological status needs a fundamental condition for having Ikigai.

Figure 2.

Biopsychosocial model of Ikigai.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: S.F. and T.I.; methodology, T.G., S.F., Y.S. and T.I.; validation, S.F., Y.S. and T.I.; formal analysis: T.G. and S.F.; investigation: T.G., S.F., T.K., T.M., M.K., Y.S. and T.I.; resources: S.F. and T.I.; data curation, T.G. and S.F.; writing—original draft preparation: T.G.; writing—review and editing: T.G., S.F. and T.I.; visualization, T.G. and T.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for scientific research from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (KAKENHI JP18H02993, JP20K10338 and JP22H03282), and the Foundation for Development of the Community.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of National Hospital Organization Kyoto Medical Center (approval number: 17-032 and date of approval: 18 July 2017). It was conducted according to the criteria set out by the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World Population Prospects 2019 Highlights; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2019; Available online: https://population.un.org/wpp/publications/files/wpp2019_highlights.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2022).

- Cantu, P.A.; Sheehan, C.M.; Sasson, I.; Hayward, M.D. Increasing education-based disparities in healthy life expectancy among U.S. non-hispanic whites, 2000–2010. J. Gerontology. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2021, 76, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christiansen, J.; Qualter, P.; Friis, K.; Pedersen, S.S.; Lund, R.; Andersen, C.M.; Bekker-Jeppesen, M.; Lasgaard, M. Associations of loneliness and social isolation with physical and mental health among adolescents and young adults. Perspect. Public Health 2021, 141, 226–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, A.; Sun, Q.; Okereke, O.I.; Rexrode, K.M.; Hu, F.B. Depression and risk of stroke morbidity and mortality: A meta-analysis and systematic review. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2011, 306, 1241–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Everson-Rose, S.A.; Lewis, T.T. Psychosocial factors and cardiovascular diseases. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2005, 26, 469–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okuzono, S.S.; Shiba, K.; Kim, E.S.; Shirai, K.; Kondo, N.; Fujiwara, T.; Kondo, K.; Lomas, T.; Trudel-Fitzgerald, C.; Kawachi, I.; et al. Ikigai and subsequent health and wellbeing among Japanese older adults: Longitudinal outcome-wide analysis. Lancet Reg. Health–West. Pac. 2022, 3, 100391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schippers, M.C.; Ziegler, N. Life Crafting as a way to find purpose and meaning in life. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumano, M. On the Concept of Well-Being in Japan: Feeling Shiawase as Hedonic Well-Being and Feeling Ikigai as Eudaimonic Well-Being. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2018, 13, 419–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirai, K.; Iso, H.; Fukuda, H.; Toyoda, Y.; Takatorige, T.; Tatara, K. Factors associated with "Ikigai" among members of a public temporary employment agency for seniors (Silver Human Resources Centre) in Japan; gender differences. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2006, 4, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oxford University Press. Oxford English Dictionary Online; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- García, H.; Miralles, F. The Japanese Secret to a Long and Happy Life; Penguin Random House: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Naoi, M. My reflections from 45 years of gerontological research and beyond. J. Gerontol. Geriatr. Res. 2018, 8, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Namihira, E. Message for the hyper-aging society; a view from anthropology of life. J. Jpn. Acad. Gerontol. Nurs. 2021, 25, 21–25. [Google Scholar]

- Sone, T.; Nakaya, N.; Ohmori, K.; Shimazu, T.; Higashiguchi, M.; Kakizaki, M.; Kikuchi, N.; Kuriyama, S.; Tsuji, I. Sense of life worth living (ikigai) and mortality in Japan: Ohsaki study. Psychosom. Med. 2008, 70, 709–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mori, K.; Kaiho, Y.; Tomata, Y.; Narita, M.; Tanji, F.; Sugiyama, K.; Sugawara, Y.; Tsuji, I. Sense of life worth living (ikigai) and incident functional disability in elderly Japanese: The Tsurugaya project. J. Psychosom. Res. 2017, 95, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. The First Ten Years of the World Health Organization; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1958; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241560146 (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Engel, G.L. The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science 1977, 196, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanji, H.; Hasegawa, A.; Sakurai, N.; Fujiwara, Y. The relationships between pleasure and IKIGAI with three year survival rate for the suburban elderly dwellers in Japan. Bull. Soc. Med. 2017, 34, 85–92. [Google Scholar]

- Washburn, R.A.; Smith, K.W.; Jette, A.M.; Janney, C.A. The Physical activity scale for the elderly (PASE): Development and evaluation. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1993, 46, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Studenski, S.; Perera, S.; Patel, K.; Rosano, C.; Faulkner, K.; Inzitari, M.; Brach, J.; Chandler, J.; Cawthon, P.; Connor, E.B.; et al. Gait speed and survival in older adults. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2011, 305, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson-Hughes, B.; Harris, S.S.; Krall, E.A.; Dallal, G.E. Effect of calcium and vitamin D supplementation on bone density in men and women 65 years of age or older. N. Engl. J. Med. 1977, 337, 670–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagiwara, A.; Ito, N.; Sawai, K.; Kazuma, K. Validity and reliability of the Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE) in Japanese elderly people. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2008, 8, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, J.I.; Yesavage, J.A. Geriatric depression scale (GDS): Recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clin. Gerontol. 1986, 5, 165–173. [Google Scholar]

- Yesavage, J.A.; Brink, T.L.; Rose, T.L.; Lum, O.; Huang, V.; Adey, M.; Leirer, V.O. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: A preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res. 1982, 17, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerin, J.M.; Copersino, M.L.; Schretlen, D.J. Clinical utility of the 15-item geriatric depression scale (GDS-15) for use with young and middle-aged adults. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 241, 59–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gnjidic, D.; Hilmer, S.N.; Blyth, F.M.; Naganathan, V.; Waite, L.; Seibel, M.J.; McLachlan, A.J.; Cumming, R.G.; Handelsman, D.J.; Le Couteur, D.G. Polypharmacy cutoff and outcomes: Five or more medicines were used to identify community-dwelling older men at risk of different adverse outcomes. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2012, 65, 989–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugishita, K.; Sugishita, M.; Hemmi, I.; Asada, T.; Tanigawa, T. A validity and reliability study of the Japanese version of the geriatric depression scale 15 (GDS-15-J). Clin. Gerontol. 2017, 40, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitrushina, M.; Satz, P. Reliability and validity of the Mini-Mental State Exam in neurologically intact elderly. J. Clin. Psychol. 1991, 47, 537–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugishita, M.; Hemmi, I.; Takeuchi, T. Reexamination of the validity and reliability of the Japanese version of the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE-J). Jpn. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2016, 18, 168–183. [Google Scholar]

- Lubben, J.E. Assessing social networks among elderly populations. Fam. Community Health 1988, 11, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.; Haley, W.E.; Small, B.J.; Mortimer, J.A. The role of mastery and social resources in the associations between disability and depression in later life. Gerontologist 2002, 42, 807–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurimoto, A.; Awata, S.; Ohkubo, T.; Tsubota-Utsugi, M.; Asayama, K.; Takahashi, K.; Suenaga, K.; Satoh, H.; Imai, Y. Reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the abbreviated Lubben Social Network Scale. Japanese J. Geriatr. 2011, 48, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schermelleh-Engel, K.; Moosbrugger, H.; Müller, H. Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: Tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. MPR Online 2003, 8, 23–74. [Google Scholar]

- Alimujiang, A.; Wiensch, A.; Boss, J.; Fleischer, N.L.; Mondul, A.M.; McLean, K.; Mukherjee, B.; Pearce, C.L. Association between life purpose and mortality among US adults older than 50 years. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e194270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKnight, P.E.; Kashdan, T.B. Purpose in life as a system that creates and sustains health and well-being: An integrative, testable theory. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2009, 13, 242–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, P.A.; Buchman, A.S.; Bennett, D.A. Purpose in life is associated with a reduced risk of incident disability among community-dwelling older persons. The Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2010, 18, 1093–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkes, J.; Garip, G.; Kotera, Y.; Fido, D. Can ikigai predict anxiety, depression, and well-being? Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2022, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakao, R.; Nitta, A.; Yumiba, M.; Ota, K.; Kamohara, S.; Ohnishi, M. Factors related to ikigai among older residents participating in hillside residential community-based activities in Nagasaki City, Japan. J. Rural Med. 2021, 16, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reker, G.T.; Wong, P.T.P. Personal meaning in life and psychosocial adaptation in the later years. In The Human Quest for Meaning, 2nd ed.; Wong, P.T.P., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; pp. 433–456. [Google Scholar]

- Sakuma, N.; Ura, C.; Miyamae, F.; Inagaki, H.; Ito, K.; Niikawa, H.; Ijuin, M.; Okamura, T.; Sugiyama, M.; Awata, S. Distribution of Mini-Mental State Examination scores among urban community-dwelling older adults in Japan. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2017, 32, 718–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujiwara, Y.; Watanabe, S.; Kumagai, S.; Yoshida, Y.; Takabayashi, K.; Morita, M.; Hasegawa, A.; Hoshi, T.; Yokobe, M.; Kita, T.; et al. Prevalence and characteristics of older community residents with mild cognitive decline. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2022, 2, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wlodarczyk, J.H.; Brodaty, H.; Hawthorne, G. The relationship between quality of life, Mini-Mental State Examination, and the Instrumental Activities of Daily Living in patients with Alzheimer's disease. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2004, 39, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seko, K.; Hirano, M. Predictors and importance of social aspects in ikigai among older women. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavanagh, A.M.; Bentley, R.; Turrell, G.; Broom, D.H.; Subramanian, S.V. Does gender modify associations between self rated health and the social and economic characteristics of local environments? J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2006, 60, 490–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, T.; Osada, H.; Nishimura, Y. The reliability and validity of a new scale for measuring the concept of Ikigai (Ikigai-9). Jpn. J. Public Health 2012, 59, 433–440. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).