Caring for Homebound Veterans during COVID-19 in the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Foster Home Program

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Recruitment

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

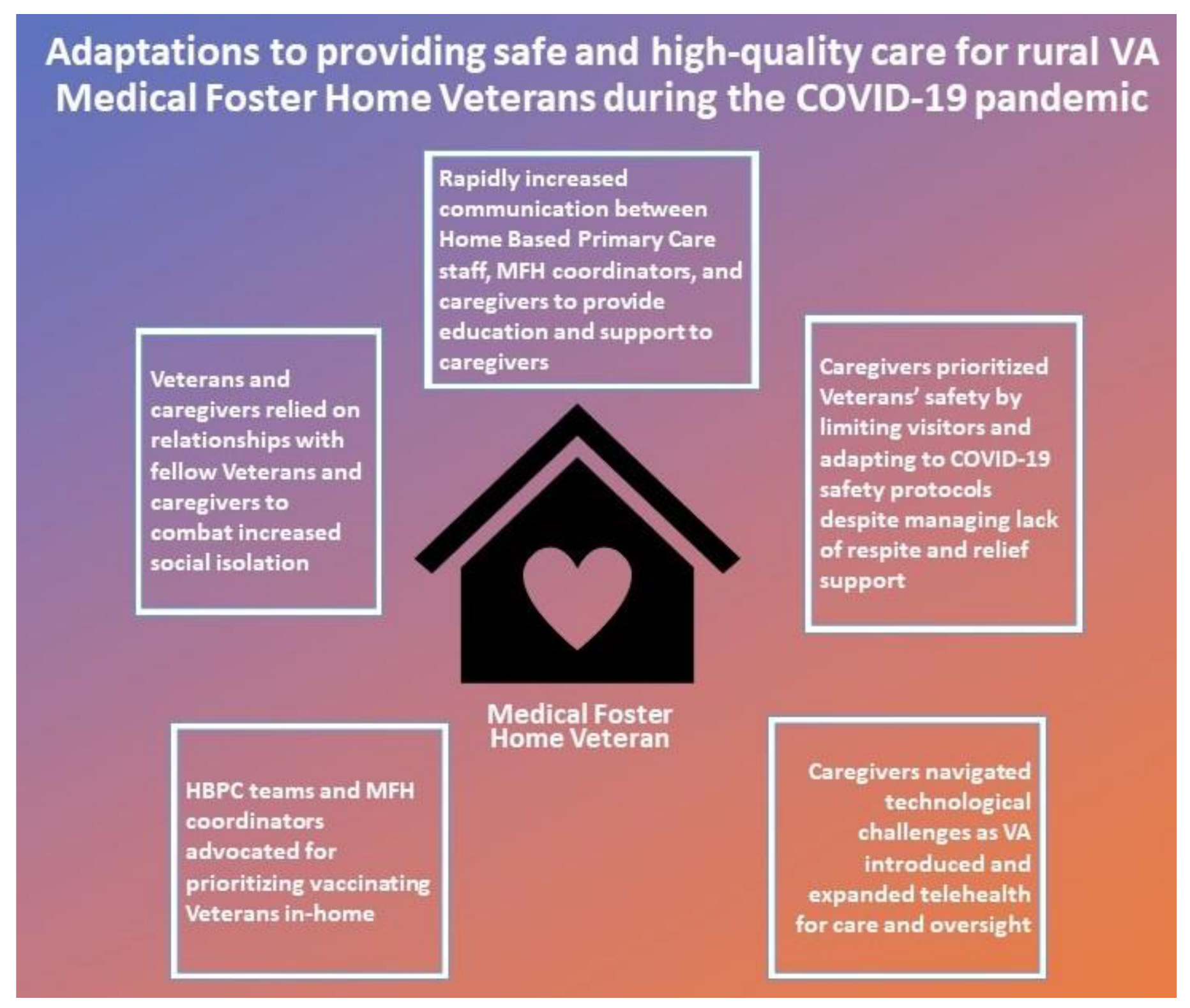

3. Results

3.1. Rapidly Increased Communication between HBPC, MFH Coordinators, and Caregivers to Provide Education and Support

Providing Caregivers Education on COVID-19

“I worked with the nurse primarily, the case manager, who was very involved, and we made a plan [for] like, routine education, framing it in a way that [was] to their level… we tried to provide the education in the context of where they were coming from.”(Coordinator, Site J)

3.2. A Shared Commitment to Prioritizing Veterans’ Safety

3.2.1. The Realities of Lack of Respite and Relief Care for Caregivers

3.2.2. Managing Day-to-Day Changes to Ensure Safety, and Continuing to Admit Veterans to MFHs

Especially during the time of the pandemic, it really shows how important these homes are. They [caregivers] have been able to successfully care for Veterans, keep them safe, keep them out of the nursing homes, which we know the nursing homes have taken such a huge hit with coronavirus. So, with the help of Home Based Primary Care, the Medical Foster Homes have been able to care for Veterans, give the care that they need, and I just think it’s very so, like so amazing to see how well these homes have done.(Coordinator, Site M)

3.3. Caregivers Navigating Technological Challenges as VA Introduced and Expanded Telehealth for Care and Oversight

3.3.1. Virtual Meetings Used for Oversight

3.3.2. Navigating Telehealth Challenges

3.4. HBPC Teams and MFH Coordinators Advocated for Prioritizing Vaccinating Veterans In-Home

3.4.1. Providing Initial Vaccine Information to Ease Concern

3.4.2. Facilitators and Barriers to Vaccine Distribution

3.4.3. Vaccine Receptivity and Intention

3.5. Veterans and Caregivers Relied on Relationships with Fellow Veterans and Caregivers to Combat Increased Social Isolation

A big part of this program is being able to have the Veterans be social and be able to be around other Veterans and other, other folks and just not be so isolated because that, the isolation really is, is bad for mental health. People need to be around other people. People need to be able to be told that they’re important and that they’re loved and cared for and that just helps their mental state.(Caregiver, Site K)

It’s been a total challenge of faith and fortitude and within like the first three months, I think was the big reconciling of what these caregivers of like ‘holy moly, this is, this is hard core.’ And so, they went through this period of like, you know, crisis mode, like ‘I don’t know if I can do this long-term, and I don’t know how this is gonna work,’ but they all adapted for the most part.(Coordinator, Site J)

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Miller, E.A. Shining a Spotlight: The Ramifications of the COVID-19 Pandemic for Older Adults. J. Aging Soc. Policy 2021, 33, 305–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esme, M.; Koca, M.; Dikmeer, A.; Balci, C.; Ata, N.; Dogu, B.B.; Cankurtaran, M.; Yilmaz, M.; Celik, O.; Unal, G.G.; et al. Older Adults With Coronavirus Disease 2019: A Nationwide Study in Turkey. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 2020, 76, e68–e75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikram, U.; Gallani, S.; Figueroa, J.F.; Feeley, T.W. Protecting Vulnerable Older Patients during the Pandemic. NEJM Catal. Innov. Care Deliv. 2020, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radwan, E.; Radwan, A.; Radwan, W. Challenges Facing Older Adults during the COVID-19 Outbreak. Eur. J. Environ. Public Health 2020, 5, em0059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooke, J.; Clark, M. Older people’s early experience of household isolation and social distancing during COVID-19. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 4387–4402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Shea, B.Q.; Finlay, J.M.; Kler, J.; Joseph, C.A.; Kobayashi, L.C. Loneliness Among US Adults Aged ≥55 Early in the COVID-19 Pandemic. Public Health Rep. 2021, 136, 754–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markkanen, P.; Brouillette, N.; Quinn, M.; Galligan, C.; Sama, S.; Lindberg, J.; Karlsson, N. “It changed everything”: The safe Home care qualitative study of the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on home care aides, clients, and managers. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, E.; Doyle, M.; McHugh, S.; Mello, S. The Lived Experience of Older Adults Transferring between Long-Term Care Facilities during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Gerontol. Nurs. 2022, 48, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, F.; Gordon, A.; Gladman, J.R.F.; Bishop, S. Care homes, their communities, and resilience in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic: Interim findings from a qualitative study. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro Prados, A.B.; Jiménez García-Tizón, S.; Meléndez, J.C. Sense of coherence and burnout in nursing home workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain. Health Soc Care Commun. 2022, 30, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinman, M.A.; Perry, L.; Perissinotto, C.M. Meeting the Care Needs of Older Adults Isolated at Home during the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Intern. Med. 2020, 180, 819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rokstad, A.M.M.; Røsvik, J.; Fossberg, M.; Eriksen, S. The COVID-19 pandemic as experienced by the spouses of home-dwelling people with dementia—A qualitative study. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haverhals, L.M.; Manheim, C.E.; Jones, J.; Levy, C. Launching Medical Foster Home Programs: Key Components to Growing This Alternative to Nursing Home Placement. J. Hous. Elder. 2017, 31, 14–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veterans Health Administration Office of Geriatrics and Extended Care Operations. VHA Directive 1141.02 Medical Foster Home Program Procedures; US Department of Veterans Affairs: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; pp. 1–31.

- Beales, J.L.; Edes, T. Veteran’s Affairs Home Based Primary Care. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2009, 25, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, C.; Whitfield, E.A. Medical Foster Homes: Can the Adult Foster Care Model Substitute for Nursing Home Care? J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2016, 64, 2585–2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medical Foster Home Locations. US Department of Veterans Affairs Website. 2022. Available online: https://www.va.gov/geriatrics/docs/VA_Medical_Foster_Home_Locations.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2022).

- Mathey, M. Personal Communication; National VA Medical Foster Home Coordinator: Washington, DC, USA, 2022.

- VA Amplifies Access to Home, Community-Based Services for Eligible Veterans. VA Office of Public and Intergovernmental Affairs. 2022. Available online: https://www.va.gov/opa/pressrel/pressrelease.cfm?id=5757 (accessed on 20 February 2022).

- Solorzano, N.C.M.; Haverhals, L.; Levy, C. Evaluation of the VA Medical Foster Home Program: Factors Important for Expansion and Sustainability during COVID-19. In GSA 2020 Annual Scientific Meeting; US Department of Veterans Affairs: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rural Veteran Health Care Challenges. VA Office of Rural Health Website. 2022. Available online: https://www.ruralhealth.va.gov/aboutus/ruralvets.asp (accessed on 15 January 2022).

- Department of Veterans Affairs. COVID-19 Guidance for Geriatrics and Extended Care Home and Community Based Services Programs; Department of Veterans Affairs Memorandum: Washington, DC, USA, 2020.

- Vaismoradi, M.; Turunen, H.; Bondas, T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs. Health Sci. 2013, 15, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atlas.ti. Scientific Software Development GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2020. Available online: https://atlasti.com/ (accessed on 12 April 2021).

- Pendergrast, C. “There Was No ‘That’s Not My Job’”: New York Area Agencies on Aging Approaches to Supporting Older Adults during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2021, 40, 1425–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, K.H.M.; Mak, A.K.P.; Chung, R.W.M.; Leung, D.Y.L.; Chiang, V.C.L.; Cheung, D.S.K. Implications of COVID-19 on the Loneliness of Older Adults in Residential Care Homes. Qual. Health Res. 2022, 32, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaeta, L.; Brydges, C.R. Coronavirus-Related Anxiety, Social Isolation, and Loneliness in Older Adults in Northern California during the Stay-at-Home Order. J. Aging Soc. Policy 2021, 33, 320–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouslander, J.G.; Grabowski, D.C. COVID-19 in Nursing Homes: Calming the Perfect Storm. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2020, 68, 2153–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, W.A.; Harris, L.M.; Heller, K.E.; Mitchell, B.D. “We Are Saving Their Bodies and Destroying Their Souls.”: Family Caregivers’ Experiences of Formal Care Setting Visitation Restrictions during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Aging Soc. Policy 2021, 33, 398–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbasi, J. Social Isolation—the Other COVID-19 Threat in Nursing Homes. JAMA 2020, 324, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osakwe, Z.T.; Osborne, J.C.; Samuel, T.; Bianco, G.; Céspedes, A.; Odlum, M.; Stefancic, A. All alone: A qualitative study of home health aides’ experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic in New York. Am. J. Infect. Control 2021, 49, 1362–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilman, C.; Haverhals, L.; Manheim, C.; Levy, C. A qualitative exploration of veteran and family perspectives on medical foster homes. Home Health Care Serv. Q. 2017, 37, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manheim, C.E.; Haverhals, L.M.; Jones, J.; Levy, C.R. Allowing Family to be Family: End-of-Life Care in Veterans Affairs Medical Foster Homes. J. Soc. Work End Life Palliat. Care 2016, 12, 104–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magid, K.H.; Solorzano, N.; Manheim, C.; Haverhals, L.M.; Levy, C. Social Support and Stressors among VA Medical Foster Home Caregivers. J. Aging Soc. Policy 2021, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyte-Lake, T.; Manheim, C.; Gillespie, S.M.; Dobalian, A.; Haverhals, L.M. COVID-19 Vaccination in VA Home Based Primary Care: Experience of Interdisciplinary Team Members. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2022, 23, 917–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.Y.; Mehrotra, A.; Huskamp, H.A.; Uscher-Pines, L.; Ganguli, I.; Barnett, M.L. Variation in Telemedicine Use and Outpatient Care During The COVID-19 Pandemic in the United States. Health Aff. 2021, 40, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manheim, C.E.; Wang, H.; Intrator, O.; Levy, C.; Haverhals, L.M.; Solorzano, N. VA Medical Foster Home Care Pivoted to Telehealth during COVID-19 Pandemic. In Proceedings of the Academy Health Conference, Virtual, 14–17 June 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Franzosa, E.; Gorbenko, K.; Brody, A.A.; Leff, B.; Ritchie, C.S.; Kinosian, B.; Sheehan, O.C.; Federman, A.D.; Ornstein, K.A. “There Is Something Very Personal About Seeing Someone’s Face”: Provider Perceptions of Video Visits in Home-Based Primary Care During COVID-19. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2021, 40, 1417–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Der-Martirosian, C.; Wyte-Lake, T.; Balut, M.; Chu, K.; Heyworth, L.; Leung, L.; Ziaeian, B.; Tubbesing, S.; Mullur, R.; Dobalian, A. Implementation of Telehealth Services at the US Department of Veterans Affairs during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Mixed Methods Study. JMIR Form. Res. 2021, 5, e29429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coe, N.B.; Werner, R.M. Informal Caregivers Provide Considerable Front-Line Support in Residential Care Facilities and Nursing Homes. Health Aff. 2022, 41, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fulmer, T.; Reuben, D.B.; Auerbach, J.; Fick, D.M.; Galambos, C.; Johnson, K.S. Actualizing Better Health and Health Care for Older Adults. Health Aff. 2021, 40, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Participant Characteristics | Number of Total Respondents N = 37 | |

|---|---|---|

| Participant Role | MFH Caregiver | 13 |

| HBPC Provider | 11 | |

| Coordinators | 13 | |

| Age Range of Caregivers | 50–59 years old | 3 |

| 60–69 years old | 6 | |

| 70–79 years old | 4 | |

| Role of HBPC Provider | Registered Nurse | 5 |

| Nurse Practitioner | 3 | |

| Psychologist | 1 | |

| 3.1. Rapidly increased communication between HBPC, MFH coordinators, and caregivers to provide education and support | Caregiver, site K: “I think they [VA] did the best they could, absolutely, without, you know, putting themselves and others at risk… and they jumped on it pretty quick… it didn’t take them long to, to see what was going on and react to it as far as communicating with the Veterans via different ways…I think they did an excellent job.” |

| Caregiver, site A: “You know, of course, if I need anything, she [MFH Coordinator] is always there, just a phone call away, so I get quite a bit of support actually from the VA, which I am very glad and thankful for…I have a very good team that works with me and communication is very good… their support’s awesome.” | |

| Coordinator, site H: “When the travel was restricted, to keep up with the caregivers, I started doing a weekly caregiver call just to touch base with them, and kind of, like a support group, so they could network with other caregivers on the phone.” | |

| 3.11. Providing caregivers education on COVID-19 | Coordinator, site J: “The whole team, like the HBPC team… we would discuss the challenges of the homes, and how this one was particularly more resistant to education. And so, I worked with the nurse primarily, the case manager, who was very involved, and we made a plan like, routine education, framing it in a way that [was] to their level… they’re high school graduates. They’ve done primarily like, blue collar work, and they’ve been caregivers for many years, so, it’s not like they didn’t know what they were doing, but it was… we tried to provide the education in the context of where they were coming from.” |

| Caregiver, Site B: “In the beginning… we’ve got an area coordinator. She calls and talks to the guys, we’ve got a… kind of like a counselor talks to them on the phone. We’ve got a [HBPC] psychologist that will call and talk to any of them, so I’ve got a great support system, and it’s just we’ve transferred it from being on, in-person, to everybody being online.” | |

| 3.2. A shared commitment to prioritizing Veterans’ safety | HBPC Provider, Site C: “Our caregivers are top notch and, and if they had any concerns at all, they would give us a call, which we encouraged… they were prepared for anything.” |

| 3.2.1. Realities of lack of respite and relief care for caregivers | Caregiver, Site D: “We could not do respite anymore for them [Veterans] and we had to be careful about who come into our home and people had to wear masks and stuff… so every time they [HHA] come, we have to do their temperature and stuff like that. So, they made sure that they put the foundation in on what we had to do to keep the guys safe…It was, it was a little stressful at first. I’m not gonna lie.” |

| HBPC Provider, Site E: “Due to COVID, we are seeing a reduction in caregivers [HHA] that, that want to come to the home. They, we are having issues finding enough aides to work with our Veterans and that’s for several reasons… we contract with home health agencies… and we are finding that there seems to be a shortage of caregivers now because of COVID. Some of them, you know, aides, they don’t want to work because of the risk of COVID.” | |

| Caregiver, Site L: “We [MFH caregivers] all network together, so, what I did when I had the two weeks in December, I had to take them [Veterans] to get COVID test at the VA and it was a drive-thru, and they gave us a result two hours later and once they were OK, then I packed them up, and took [them], and then the caregiver that they were going to had to have a COVID test and whoever lives in that house had to have a COVID test… and I took them, and they stayed two weeks, and then you go back and pick them up two weeks later.” | |

| 3.2.2. Managing day-to-day changes to ensure safety, and continuing to admit Veterans to MFHs | Caregiver, Site J: “Before the pandemic, it was easy. I didn’t have any fear. I didn’t have any struggles. Then, after that [the pandemic] came in, I had to start thinking differently about where to take them [Veterans], what to do with them and who to let in the house and make sure everybody washed their hands a thousand times a day, just, just to keep them safe, it is a, it has been a total change, of course, not just for me but for everybody else, it’s been a total change for our habits and our approach to things and what we do during the day.” |

| Caregiver, Site B: “We thought it was gonna be temporary, so in the beginning, right off the bat, everybody was pretty good with it… cause nobody wanted to get sick. You know, they were all capable of understanding and… if one of them got sick, then the rest of them could get sick and anybody could die from it… it’s only gotten rougher as it’s gotten on, and they can’t see the family.” | |

| Caregiver, Site K: “Visitors could not come for a while because that was our state governor that ruled that. And then, once that was released then visitors were supposed to, you know, wear masks and social distancing type thing.” | |

| Caregiver, Site L: “It’s kind of hard because you’re having to make sure that whoever comes in the house doesn’t bring anything and when we go somewhere that we’re not gonna be exposed to it or vice versa… but were hanging in there, and they [Veterans] understand the reason why we don’t go as much and why we don’t let as many people come in the home because we just don’t want anyone sick with the virus.” | |

| Coordinator, Site F: “They [Veterans’ families] know the [COVID-19] numbers of going into assisted living or to a nursing home, their numbers are way higher, you know, I don’t know what the numbers are throughout the United States for Medical Foster Homes, but I think it’s kind of low as far as the COVID positive tests that have been received in the Medical Foster Home versus the nursing home. So, most families are all in for the Medical Foster Home program versus placing them in a nursing home, and then that would stop them from visiting the Veteran. If they’re in a nursing home, they can’t go in and visit. So, I think that’s one of the things that they all, you know, took into consideration when placing them into a Medical Foster Home.” | |

| 3.3. Caregivers navigating technological challenges as VA introduced and expanded telehealth for care and oversight | HBPC Provider, Site K: “There is a great dependence of the Veterans on the Medical Foster Home caregivers to navigate and utilize the technology because they [MFH Veteran], for the most part, cannot do that. I have some that can, but I would say 75% of my Medical Foster Home patients cannot navigate that technology independently.” |

| Caregiver, Site K: “VA has a special…their own type of video chat type thing…where you actually can see the, your doctor or your dietician or your psychiatrist or whichever, you know, provider it is face-to-face, and you can communicate and that way they can put eyes on the Veteran and ask questions, interview them, so that’s been, that’s been a really, a really good help.” | |

| HBPC Provider; Site J: “I think one of the benefits of the Medical Foster Home program is obviously the caregiver, and we’ve been able to set all of our caregivers up with the Video Veterans Connection service, so we’re able to see our Veterans through the Video Connect program. So, we’re able to see them more safely without exposing them and the families to possible infection.” | |

| 3.3.2. Navigating telehealth challenges | Coordinator, Site C: “A lot of my Veterans actually get sort of angry, especially with the mental health side. The mental health folks are very strict on absolutely no in-clinic visits… because they’re [the Veteran] like ‘I need to see a mental health provider face-to-face. I don’t like doing this video connect’, plus it doesn’t work sometimes.” |

| Caregiver, Site A: “I was more happier when we was more face-to-face. I thought we could communicate more. It is OK that way [telehealth care], but I’m the kind of person, like, hands-on to like to be in the, in the situation to understand it more.” | |

| 3.4.1. Providing initial vaccine information to ease concern | Coordinator, Site K: “That they have decided locally is that Veterans that participate in Home Based Primary Care are in higher need than the normal population, so we’re really first in line along with folks in CLC [VA nursing homes known as Community Living Centers]… so we have already started scheduling for our Veterans to go and get those vaccines started.” |

| Coordinator, Site H: “Once I know for sure what our VA’s plan is going to be moving forward and then how rapidly we will get it distributed to our patients in our Medical Foster Home, I am prepared. I took an extra training yesterday on the TMS [VA’s Training Management System] specifically about how to communicate regarding the vaccine to caregivers and Veterans, so I got more tips and tools from that training as far as… having the open lines of communication, discussing maybe what their perceptions of vaccines are and where they’re at with their knowledge base, and then try to enhance their knowledge of… the COVID vaccine. I’m trying to get myself prepared from that standpoint to be the communicator and the educator for when we do start inoculating our Veterans.” | |

| 3.4.2. Facilitators and barriers to vaccine distribution | Coordinator, Site N: “I think the big question now is trying to figure out how to get the Medical Foster Home Veterans that are unable to get out to the site…our facility is only doing the vaccine through the drive-thru site… in the hospital, and so a lot of our caregivers… can’t provide that service getting them in there just because of limited caregiving, you know, limited support caregivers or being able to safely transport due to mobility issues with the Veteran.” |

| Caregiver, Site G: “We would have to drive 60 miles to VA facility. We were wondering if it would be possible to just take [the] Veteran to a local Walgreens instead of taking him to VA. Also, a [family] caregiver appears to have some hesitancy about having the Veteran take it [the COVID-19 vaccine] himself. Not sure how the Veteran really feels about taking it because of his dementia, he sometimes seems to understand what is being asked and other times he seems like he doesn’t care.” | |

| 3.4.3. Vaccine receptivity and intention | Coordinator, Site M: “I feel like the caregivers would just… allow the Veteran to have autonomy in terms if the Veteran wants to get it, but since, you know, we are a pretty small program, I would think that the caregivers are wanting to do whatever they gotta do to kind of get things back to normal.” |

| Caregiver, Site J: “They don’t know how long it will last [the vaccine], is it a two-week thing, will it keep you from having the virus for two weeks or do you have to have [the vaccine] again… Those are the questions that I hear but I have not heard anything more than that.” | |

| 3.5. Veterans and caregivers relied on relationships with fellow Veterans and caregivers to combat increased social isolation | Caregiver, Site J: “First of all being at home, I’m a social person, I like to hug, I like to talk, I like friends, I like to be around other people. And one of my clients [Veterans] is like that, also. When the pandemic set in, and we couldn’t go anywhere and you couldn’t have anybody in the house, we spent a lot more time talking about the past, what he can remember and over and over again, I hear about the same things and he would listen to what I would have to say about my memories of things that had occurred in my family and stuff. He’s very social, and it was, it was good for both of us… It kept us both active.” |

| HBPC Provider, Site J: “It was nice because, we might have one caregiver that would say ‘Hey, you know, this is kind of what we’re facing,’ and then another caregiver may say, ‘well, you know, we faced that, too, and this is kind of what we’ve done to address that or these are some ideas that, you know, we’ve tried’ and they’ve really helped, you know, helped at my house.” | |

| Caregiver, Site D: “It’s been a little stressful in certain areas because we wouldn’t be able to go a lot of places, and I wasn’t able to take a vacation, and so, it’s like 24/7 you’re with the Vets all the time and you’re different with, you’re dealing with different moods and because they’re tired, too. So, what I would do is like I go outside a lot with them and do different things, so, I would put them in the van, and we would ride to the park, we would get out and have lunch to kind of diffuse the situation of the being depressed or tired or the same situation day after day.” |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Haverhals, L.M.; Manheim, C.E.; Katz, M.; Levy, C.R. Caring for Homebound Veterans during COVID-19 in the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Foster Home Program. Geriatrics 2022, 7, 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics7030066

Haverhals LM, Manheim CE, Katz M, Levy CR. Caring for Homebound Veterans during COVID-19 in the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Foster Home Program. Geriatrics. 2022; 7(3):66. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics7030066

Chicago/Turabian StyleHaverhals, Leah M., Chelsea E. Manheim, Maya Katz, and Cari R. Levy. 2022. "Caring for Homebound Veterans during COVID-19 in the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Foster Home Program" Geriatrics 7, no. 3: 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics7030066

APA StyleHaverhals, L. M., Manheim, C. E., Katz, M., & Levy, C. R. (2022). Caring for Homebound Veterans during COVID-19 in the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Foster Home Program. Geriatrics, 7(3), 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics7030066