Concerns of Quality and Reliability of Educational Videos Focused on Frailty Syndrome on YouTube Platform

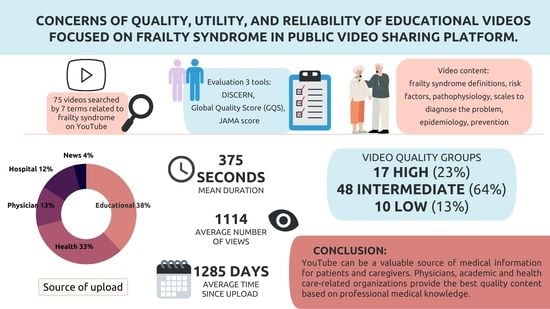

Abstract

:1. Introduction

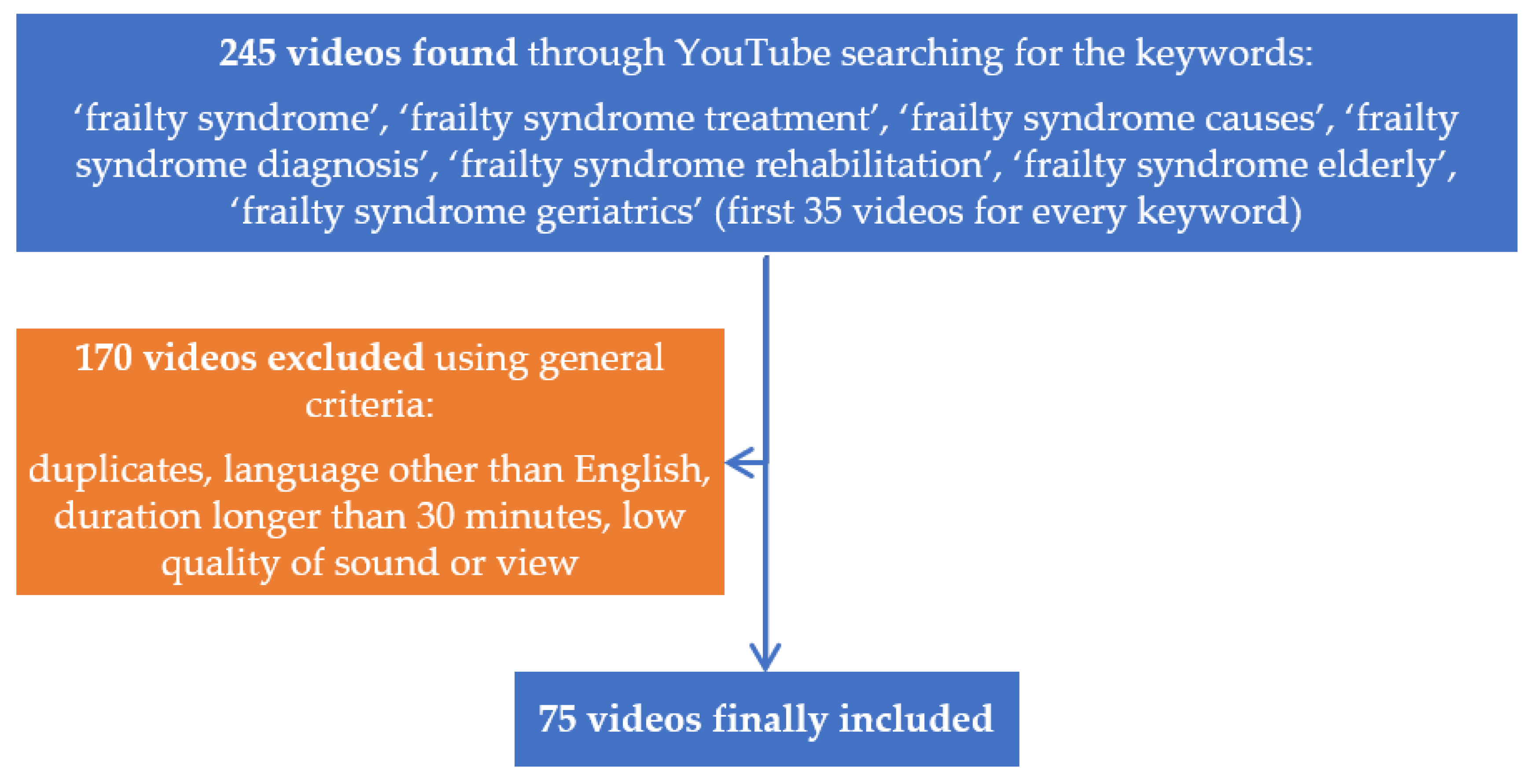

2. Materials and Methods

Statistical Analysis

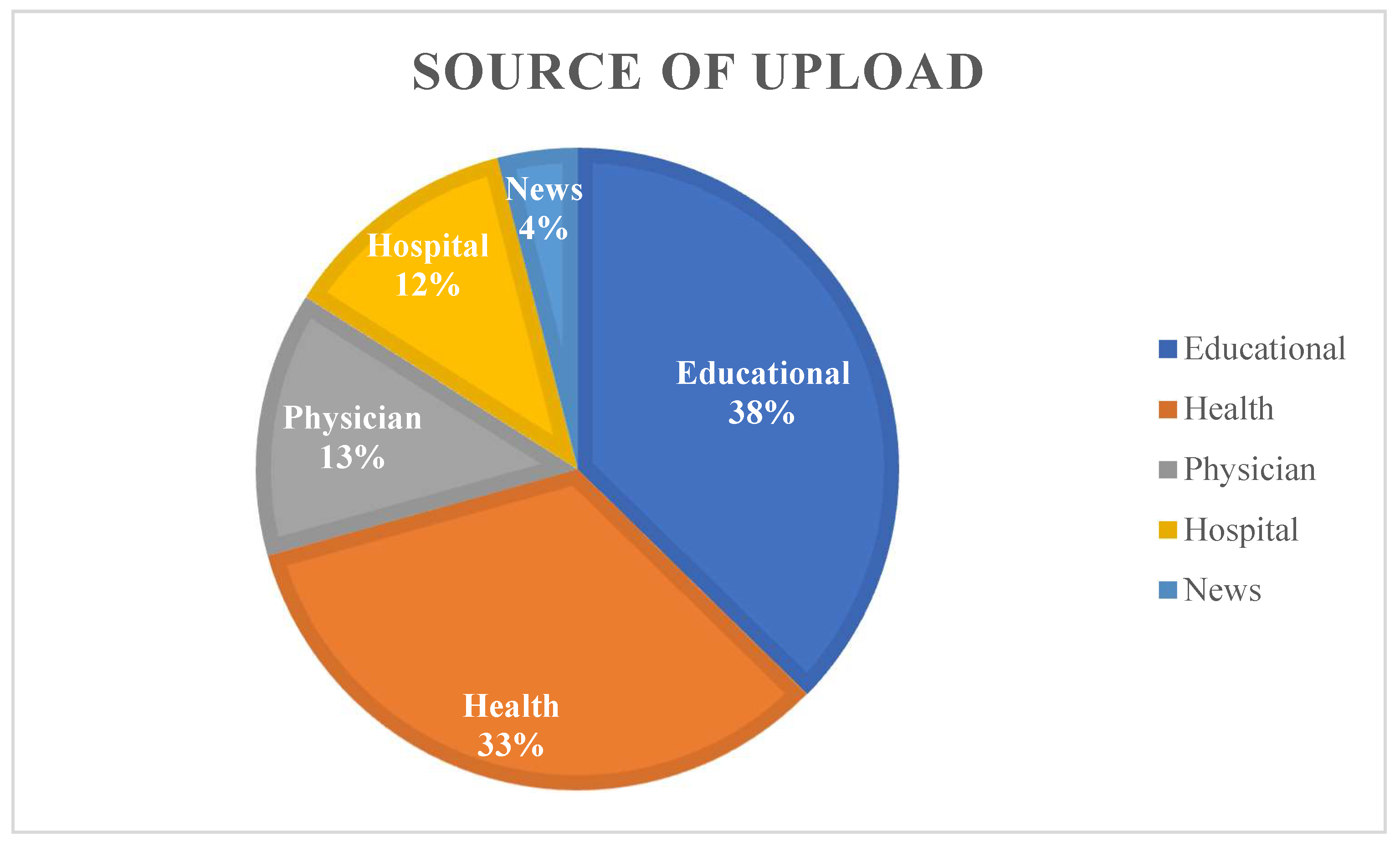

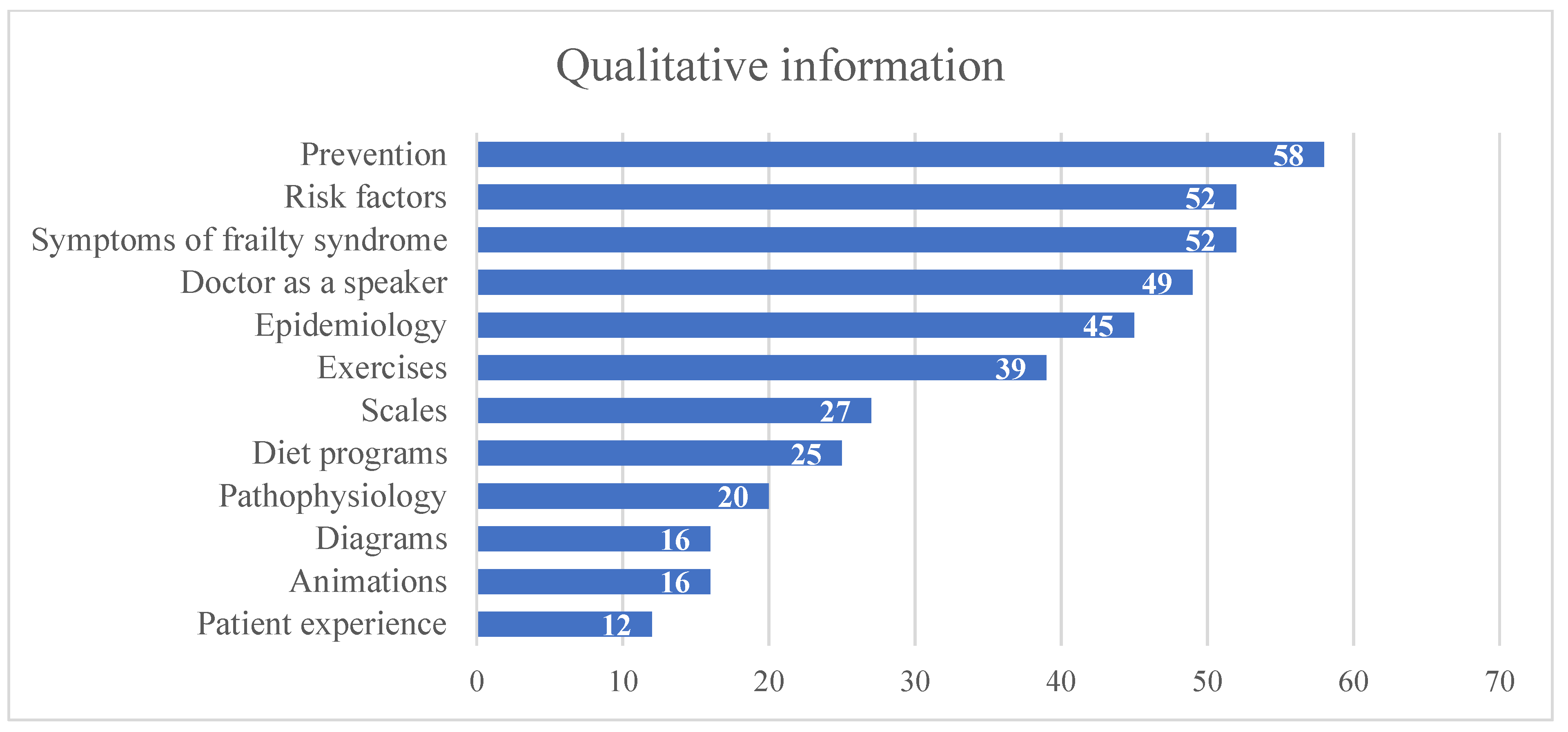

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Prevalence of frailty at population level in European ADVANTAGE Joint Action Member States: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Dell’istituto Super. Di Sanita 2018, 54, 226–238. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Clinical Consortium on Healthy Ageing: Topic Focus: Frailty and Intrinsic Capacity: Report of Consortium Meeting, 1–2 December 2016, Geneva, Switzerland; No. WHO/FWC/ALC/17.2; World Health Organization: Genevan, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Leng, S.; Chen, X.; Mao, G. Frailty syndrome: An overview. Clin. Interv. Aging 2014, 9, 433–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cybulski, M.; Krajewska-Kułak, E. Wielkie zespoły geriatryczne. Edra Urban Partn. 2021, 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Pel-Littel, R.E.; Schuurmans, M.J.; Emmelot-Vonk, M.H.; Verhaar, H.J.J. Frailty: Defining and measuring of a concept. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2009, 13, 390–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, Q.-L. The Frailty Syndrome: Definition and Natural History. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2011, 27, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Buigues, C.; Juarros-Folgado, P.; Fernandez-Garrido, J.; Navarro-Martínez, R.; Cauli, O. Frailty syndrome and pre-operative risk evaluation: A systematic review. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2015, 61, 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amante, D.J.; Hogan, T.P.; Pagoto, S.L.; English, T.M.; Lapane, K.L. Access to care and use of the Internet to search for health information: Results from the US National Health Interview Survey. J. Med. Internet Res. 2016, 18, e184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akyol, A.; Karahan, I. Is YouTube a quality source of information on sarcopenia? Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2020, 11, 693–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szmuda, T.; Özdemir, C.; Fedorow, K.; Ali, S.; Słoniewski, P. YouTube as a source of information for narcolepsy: A content-quality and optimization analysis. J. Sleep Res. 2020, 30, e13053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gokcen, H.B.; Gumussuyu, G. A Quality Analysis of Disc Herniation Videos on YouTube. World Neurosurg. 2019, 124, e799–e804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esen, E.; Aslan, M.; Sonbahar, B.; Kerimoğlu, R.S. YouTube English videos as a source of information on breast self-examination. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2018, 173, 629–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charnock, D.; Shepperd, S.; Needham, G.; Gann, R. DISCERN: An instrument for judging the quality of written consumer health information on treatment choices. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 1999, 53, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Statistics. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/intl/en-GB/yt/about/press/ (accessed on 25 August 2021).

- Cetin, A. Evaluation of YouTube Video Content Related to the Management of Hypoglycemia. Cureus 2021, 13, e12525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onder, M.; Zengin, O. YouTube as a source of information on gout: A quality analysis. Rheumatol. Int. 2021, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, C.H.; Lim, G.R.S.; Fong, W. Quality of English-language videos on YouTube as a source of information on systemic lupus erythematosus. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 2020, 23, 1636–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erdem, M.; Karaca, S. Evaluating the Accuracy and Quality of the Information in Kyphosis Videos Shared on YouTube. Spine 2018, 43, E1334–E1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| DISCERN | |

|---|---|

| Section 1 | Is the publication reliable? |

| 1 | Are the aims clear? |

| 2 | Does it achieve its aims? |

| 3 | Is it relevant? |

| 4 | Is it clear what sources of information were used to compile the publication (other than the author or producer)? |

| 5 | Is it clear when the information used or reported in the publication was produced? |

| 6 | Is it balanced and unbiased? |

| 7 | Does it provide details of additional sources of support and information? |

| 8 | Does it refer to areas of uncertainty? |

| Section 2 | How good is the quality of information? |

| 9 | Does it describe how each treatment works? |

| 10 | Does it describe the benefits of each treatment? |

| 11 | Does it describe the risks of each treatment? |

| 12 | Does it describe what would happen if no treatment were used? |

| 13 | Does it describe how the treatment choices affect overall quality of life? |

| 14 | Is it clear that there may be more than one possible treatment choice? |

| 15 | Does it provide support for shared decision-making? |

| 16 | Based on the answers to all of the above questions, rate the overall quality of the publication as a source of information about treatment choices |

| JAMA Scoring System | |

|---|---|

| Authorship | Authors and contributors, their affiliations, and relevant credentials should be provided |

| Attribution | References and sources for all content should be listed clearly, and all relevant copyright information should be noted |

| Disclosure | Website “ownership” should be prominently and fully disclosed, as should any sponsorship, advertising, underwriting, commercial funding arrangements or support, or potential conflicts of interest |

| Currency | Dates when the content was posted and updated should be posted |

| Low Quality | Intermediate Quality | High Quality | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Educational channel | 2 (7%) | 24 (86%) | 2 (7%) | 28 (38%) |

| Health channel | 6 (24%) | 11 (44%) | 8 (32%) | 25 (33%) |

| Physician channel | 0 | 5 (50%) | 5 (50%) | 10 (13%) |

| Hospital channel | 2 (22%) | 6 (67%) | 1 (11%) | 9 (12%) |

| News channel | 0 | 2 (67%) | 1 (33%) | 3 (4%) |

| TOTAL | 10 (13%) | 48 (64%) | 17 (23%) | 75 |

| Quality | Duration (Seconds) | Views | DISCERN Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| low | 285 (63–1168) | 946 (60–2336) | 2.77 |

| intermediate | 358 (42–1632) | 1097 (2–11479) | 3.31 |

| high | 478 (140–1087) | 1261 (16–6222) | 3.91 |

| Source of Upload | DISCERN Mean ± SD | GQS Mean ± SD | JAMA Mean ± SD | Duration | Views | Likes | Dislikes | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physician | 3.75 ± 0.39 | 3.75 ± 0.68 | 2.65 ± 1.00 | 509 (171–977) | 1283 (40–6222) | 10.60 (0–45) | 0.30 (0–3) | 0.70 (0–4) |

| News | 3.69 ± 0.38 | 3.33 ± 1.04 | 2.67 ± 0.76 | 511 (55–1338) | 63 (16–137) | 0.33 (0–1) | 0 | 0 |

| Educational channel | 3.33 ± 0.49 | 3.04 ± 0.58 | 2.73 ± 0.80 | 390 (42–1632) | 1200 (2–6802) | 5.43 (0–17) | 0.21 (0–2) | 0.53 (0–7) |

| Health channel | 3.28 ± 0.52 | 3.06 ± 0.83 | 2.58 ± 0.88 | 328 (63–1022) | 1036 (6–11479) | 6.12 (0–61) | 0.24 (0–2) | 0.28 (0–2) |

| Hospital channel | 3.24 ± 0.50 | 2.72 ± 0.62 | 2.78 ± 0.97 | 230 (65–872) | 1112 (104–4419) | 4.89 (0–12) | 0.11 (0–1) | 0.22 (0–1) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hawryluk, N.M.; Stompór, M.; Joniec, E.Z. Concerns of Quality and Reliability of Educational Videos Focused on Frailty Syndrome on YouTube Platform. Geriatrics 2022, 7, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics7010003

Hawryluk NM, Stompór M, Joniec EZ. Concerns of Quality and Reliability of Educational Videos Focused on Frailty Syndrome on YouTube Platform. Geriatrics. 2022; 7(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics7010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleHawryluk, Natalia Maria, Małgorzata Stompór, and Ewelina Zofia Joniec. 2022. "Concerns of Quality and Reliability of Educational Videos Focused on Frailty Syndrome on YouTube Platform" Geriatrics 7, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics7010003

APA StyleHawryluk, N. M., Stompór, M., & Joniec, E. Z. (2022). Concerns of Quality and Reliability of Educational Videos Focused on Frailty Syndrome on YouTube Platform. Geriatrics, 7(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics7010003