A Scoping Review: Social Participation as a Cornerstone of Successful Aging in Place among Rural Older Adults

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Lived Experience and Successful Aging

1.2. Aging in Place

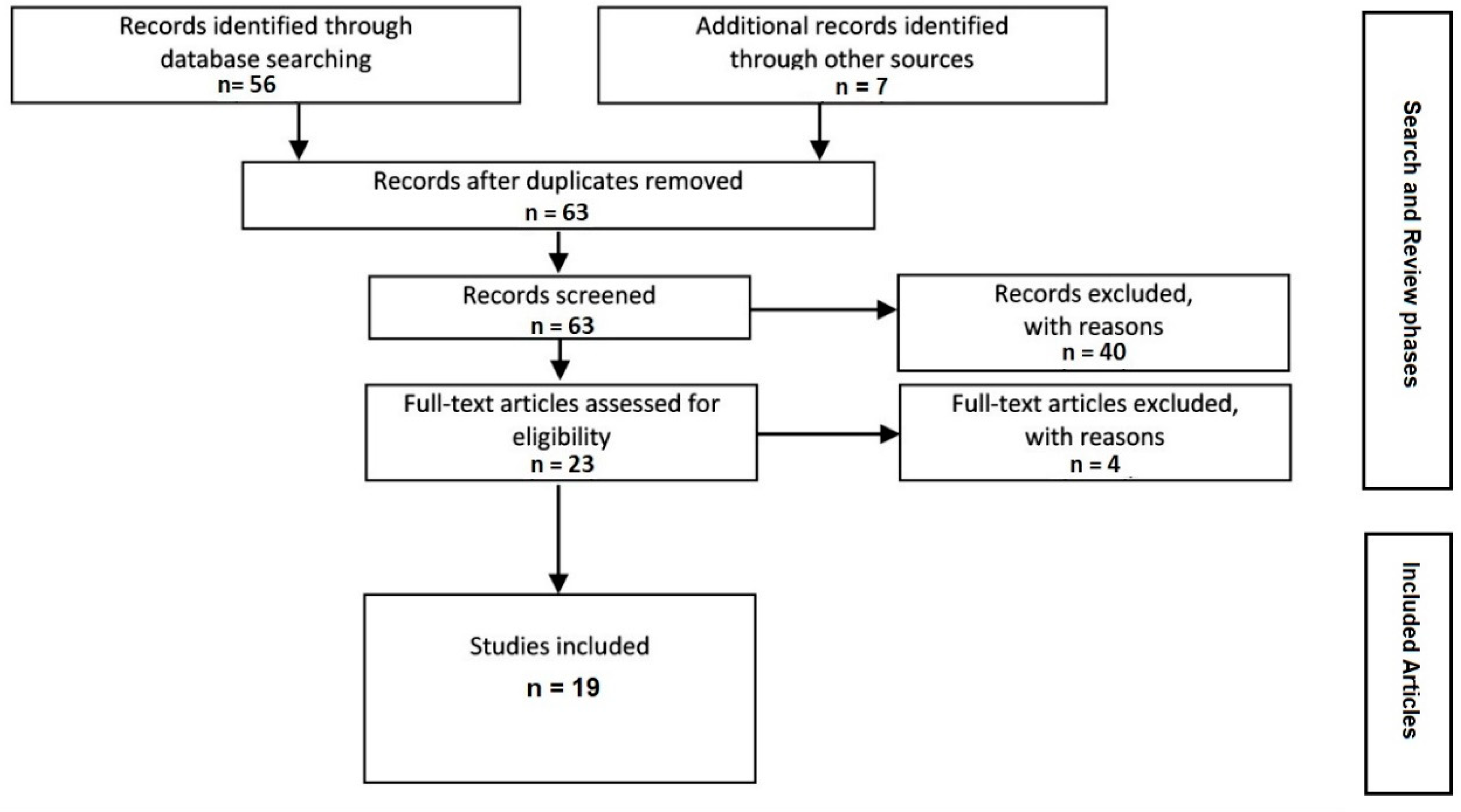

2. Methods

Search Strategy

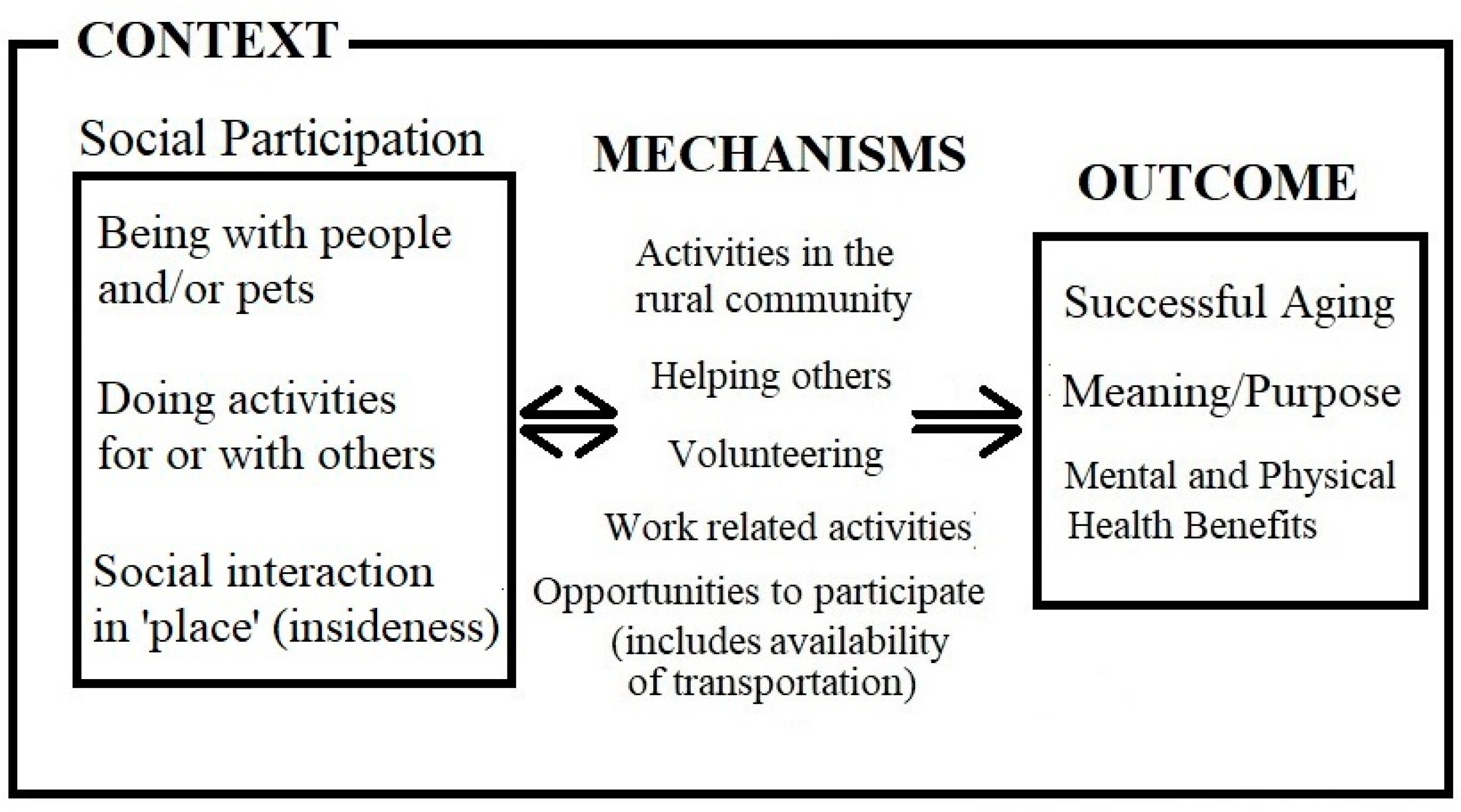

3. Results

3.1. Being with People and Pets

“There’s no doubt that there’s a lot of very disadvantaged, lonely, frail older people in town. And in farm houses around outside of the town … we’re not meeting every older person’s need, not by a long shot”[64] (p. 270)

3.2. Doing Activities with and for Others

3.3. Attachment to Place

“If I lived anywhere else, I’d be a nobody. I wouldn’t have the position I do.”Beatrice, 83 years old [21] (p. 303)

4. Discussion

Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Buys, L.; Burton, L.; Cuthill, M.; Hogan, A.; Wilson, B.; Baker, D. Establishing and maintaining social connectivity: An understanding of the lived experiences of older adults residing in regional and rural communities: Ageing in regional and rural communities. Aust. J. Rural Health 2015, 23, 291–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Q.; Cui, Y.; Liang, L.; Zhong, Q.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Lv, X.; Huang, F. Social participation, willingness and quality of life: A population-based study among older adults in rural areas of China. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2017, 17, 1593–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsh, C.; Agius, P.A.; Jayakody, G.; Shajehan, R.; Abeywickrema, C.; Durrant, K.; Luchters, S.; Holmes, W. Factors associated with social participation amongst elders in rural Sri Lanka: A cross-sectional mixed methods analysis. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du Plessis, V.; Beshiri, R.; Bollman, R.; Clemenson, H. Rural and Small Town Canada Analysis Bulletin. In Definitions of Rural; Catalogue no. 21-006-XIE; Statistics Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2001; Chapter 3; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, S.; Bartlett, H. Healthy ageing in rural Australia: Issues and challenges: Rural healthy ageing. Australas. J. Ageing 2008, 27, 56–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keating, N.; Phillips, J. A critical human ecology perspective on rural ageing. In Rural Ageing: A Good Place to Grow Old? Keating, N., Ed.; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2008; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crooks, V.A.; Castleden, H.; Schuurman, N.; Hanlon, N. Visioning for secondary palliative care service hubs in rural communities. BMC Palliat. Care 2009, 8, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, C.A.; Pesut, B.; Bottorff, J.L.; Mowry, A.; Broughton, S.; Fyles, G. Rural palliative care: A comprehensive review. J. Palliat. Med. 2009, 12, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allan, D.; Cloutier-Fisher, D. Health service utilization among older adults in British Columbia: Making sense of geography. Can. J. Aging 2006, 25, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, L.; Bombin, M.; Chi, F.; deBortoli, T.; Long, J. Use of the emergency room in Elliot Lake, a rural community of Northern Ontario, Canada. Rural Remote Health 2004, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- De Coster, C.; Bruce, S.; Kozyrskyi, A. Use of acute care hospitals by long-stay patients: Who, how much, and why? Can. J. Aging 2005, 24 (Suppl. 1), 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, M.; Hemingway, D. Older, northern and female: Reflections on health and wellness. Perspectives 2009, 31, 22–23. [Google Scholar]

- Davenport, J.; Rathwell, T.A.; Rosenberg, M.W. Service provision for seniors: Challenges for communities in Atlantic Canada. Healthc. Q. 2005, 8, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keating, N. Aging in Rural Canada; Butterworths: Toronto, ON, Canada, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Keating, N.; Swindle, J.; Fletcher, S. Aging in rural Canada: A retrospective and review. Can. J. Aging 2011, 30, 323–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Couton, P.; Gaudet, S. Rethinking social participation: The case of immigrants in Canada. J. Int. Migr. Integr. 2008, 9, 21–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogelsang, E.M. Older adult social participation and its relationship with health: Rural urban differences. Health Place 2016, 42, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Additional Protocol to the European Social Charter; European Treaty Series—No. 128; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 1988.

- Douglas, H.B.; Georgiou, A.; Westbrook, J. Social participation as an indicator of successful aging: An overview of concepts and their associations with health. Aust. Health Rev. 2017, 41, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grewal, I.; Lewis, J.; Flynn, T.; Brown, J.; Bond, J.; Coast, J. Developing attributes for a generic quality of life measure for older people: Preferences or capabilities? Soc. Sci. Med. 2006, 62, 1891–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowles, G.D. Place and personal Identity in old age: Observations from Appalachia. J. Environ. Psychol. 1983, 3, 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, K.R.; Kim, M.Y.; Kim, Y.H. Study on the lived experience of aging. Nurs. Health Sci. 2003, 5, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reichstadt, J.; Sengupta, G.; Depp, C.; Palinkas, L.A.; Jeste, D.V. Older adults’ perspectives on successful aging: Qualitative interviews. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2010, 18, 567–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wondolowski, C.; Davis, D.K. The lived experience of aging in the oldest old: A phenomenological study. Am. J. Psychoanal. 1988, 48, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapman, S.A. Aging well: Emplaced over time. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2009, 29, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumming, E.; Henry, W.E. Growing Old: The Process of Disengagement; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Jonas, C.M. The meaning of being an elder in Nepal. Nurs. Sci. Q. 1992, 5, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erikson, E.H. Childhood and Society; W.W. Norton: New York, NY, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson, E.H.; Erikson, J.M. The Life Cycle Completed (Extended Version with New Chapters on the Ninth Stage of Development); W.W. Norton: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Charlton, J.I. Nothing about Us Without Us: Disability Oppression and Empowerment; University of California Press: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, R. Writing the othered self: Autoethnography and the problem of objectification in writing about illness and disability. Qual. Health Res. 2008, 18, 1717–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosel, N. Aging in place: Knowing where you are. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2003, 57, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, P.B. Another wrinkle in the debate about successful aging: The undervalued concept of resilience and the lived experience of dementia. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2008, 67, 43–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szanton, S.L.; Thorpe, R.J.; Boyd, C.; Tanner, E.K.; Leff, B.; Agree, E.; Xue, Q.L.; Allen, J.K.; Seplaki, C.L.; Weiss, C.O.; et al. Community aging in place, advancing better living for elders: A bio-behavioural-environmental intervention to improve function and health related quality of life in disabled older adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2011, 59, 2314–2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cvitkovich, Y.; Wister, A. Bringing in the life course: A modification to Lawton’s ecological model of aging. Hallym Int. J. Aging 2002, 4, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiles, J.; Leibing, A.; Guberman, N.; Reeve, J.; Allen, R. The Meaning of “Aging in Place” to older people. Gerontologist 2011, 52, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Global Age-Friendly Cities: A Guide. 2007. Available online: http://www.who.int/ageing/publications/Global_age_friendly_cities_Guide_English.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2018).

- Peace, S.M.; Holland, C.; Kellaher, L. Environment and Identity in Later Life; Open University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Fänge, A.M.; Oswald, F.; Clemson, L. Aging in Place in Late Life: Theory, Methodology, and Intervention. J. Aging Res. 2012, 2012, 547562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callahan, J.J. (Ed.) Aging in Place; Baywood: Amityville, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, S.A.P. Place identification and positive realities of aging. J. Cross Cult. Gerontol. 2001, 16, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapman, S.A.; Peace, S. Rurality and ageing well: “A long time here.” In Rural Ageing: A Good Place to Grow Old? Keating, N., Ed.; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2008; pp. 21–31. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller-Thomson, E.; Yu, B.; Nuru-Jeter, A.; Guralnik, J.M.; Minkler, M. Basic ADL disability and functional limitations rates among older Americans from 2000–2005: The end of decline? J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2009, 64, 1333–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erickson, L.D.; Call, V.R.A.; Brown, R.B. SOS—Satisfied or Stuck, Why Older Rural Residents Stay Put: Aging in Place or Stuck in Place in Rural Utah. Rural Sociol. 2012, 77, 408–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fergenson, M. TigerPlace: An innovative ‘aging in place’ community. Am. J. Nurs. 2013, 113, 68–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marek, K.; Stetzer, F.; Adams, S.; Popejoy, L.; Rantz, M. Aging in place versus nursing home care: Comparision of costs to Medicare and Medicaid. Res. Gerontol. Nurs. 2012, 5, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morley, J.E. Aging in place. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2012, 13, 489–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohnen, S.M.; Groenewegen, P.P.; Völker, B.; Flap, H. Neighborhood social capital and individual health. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011, 72, 660–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nummela, O.; Sulander, T.; Rahkonen, O.; Karisto, A.; Uutela, A. Social participation, trust and self-rated health: A study among ageing people in urban, semi-urban and rural settings. Health Place 2008, 14, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenfield, E.A. Using ecological frameworks to advance a field of research, practice, and policy on aging in place initiatives. Gerontologist 2012, 52, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryant, C.; Joseph, A.E. Canada’s rural population: Trends in space and implications in place. Can. Geogr. 2001, 45, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloutier-Fisher, D.; Kobayashi, K. Examining social isolation by gender and geography: Conceptual and operational challenges using population health data in Canada. Gend. Place Cult. 2009, 16, 181–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houle, L.; Salmoni, A.; Pong, R.; Laflamme, S.; Viverais-Dresler, G. Predictors of family physician use among older residents of Ontario and an analysis of the Andersen-Newman Behavior Model. Can. J. Aging 2001, 20, 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, D.; Edge, D. Canadian home care policy and practice in rural and remote settings: Challenges and solutions. J. Agromed. 2009, 14, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, K.J.; Leipert, B.D. Strengthening and sustaining social supports for rural older adults. Online J. Rural Nurs. Health Care 2007, 7, 13–26. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, R.J. A comparison of rural and urban older adults in Iowa on specific markers of successful aging. J. Gerontol. Soc. Work 2009, 52, 423–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proquest LLC. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/products-services/The-Summon-Service.html (accessed on 28 October 2018).

- Grant, N.; Hamer, M.; Steptoe, A. Social isolation and stress-related cardiovascular, lipid, and cortisol responses. Ann. Behav. Med. 2009, 37, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uchino, B.N.; Cacioppo, J.T.; Kiecolt-Glaser, J.K. The relationship between social support and physiological processes: A review with emphasis on underlying mechanisms and implications for health. Psychol. Bull. 1996, 119, 488–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens-Ratchford, R.G. Aging Well Through Long-Standing Social Occupation: A Closer Look at Social Participation and Quality of Life in a SAMPLE of community-Dwelling Older Adults. Forum on Public Policy. 2008. Available online: http://forumonpublicpolicy. com/papers08spring.html#health (accessed on 28 October 2018).

- Bacsu, J.; Jeffery, B.; Abonyi, S.; Johnson, S.; Novik, N.; Martz, D.; Oosman, S. Healthy Aging in Place: Perceptions of Rural Older Adults. Educ. Gerontol. 2014, 40, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.; Kim, J.; Park, B. The effects of health on the life satisfaction of poor and nonpoor older women in Korea. Health Care Women Int. 2014, 35, 1287–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winterton, R. Organizational Responsibility for Age-Friendly Social Participation: Views of Australian Rural Community Stakeholders. J. Aging Soc. Policy 2016, 28, 261–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Havens, B.; Hall, M.; Sylvestre, G.; Jivan, T. Social isolation and loneliness: Differences between older rural and urban Manitobans. Can. J. Aging 2004, 23, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, K.M.; Cloutier-Fisher, D.; Roth, M. Making meaningful connections: A profile of social isolation and health among older adults in small town and small city, British Columbia. J. Aging Health 2009, 21, 374–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, K.B.; Leibrandt, S.; Moon, H. A critical review of the literature on activity and well-being in later life. Ageing Soc. 2011, 31, 683–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmour, H. Social participation and the health and well-being of Canadian seniors. Health Rep. 2012, 23, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Putney, J.M. Relational Ecology: A Theoretical Framework for Understanding the Human-Animal Bond. J. Sociol. Soc. Welf. 2013, 40, 57–80. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, P.C.; Trigg, J.L.; Godber, T.; Brown, C. An Experience Sampling Approach to Investigating Associations between Pet Presence and Indicators of Psychological Wellbeing and Mood in Older Australians. Anthrozoös 2015, 28, 403–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swift, A.U.; Tate, R.B. Themes from older men’s lay definitions of successful aging as indicators of primary and secondary control beliefs over time: The Manitoba Follow-up Study. J. Aging Stud. 2013, 27, 410–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toohey, A.M.; Hewson, J.A.; Adams, C.L.; Rock, M.J. Pets, Social Participation, and Aging in-Place: Findings from the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging. Can. J. Aging 2018, 37, 200–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, T.M.; Glover, T.D. On the fence: Dog parks in the (un) leashing of community and social capital. Leis. Sci. 2014, 36, 217–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fast, J.; de Jong Gierveld, J. Ageing, disability and participation. In Rural Ageing: A Good Place to Grow Old? Keating, N., Ed.; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2008; pp. 63–73. [Google Scholar]

- Witcher, C.; Holt, N.; Spence, J.; Cousins, S. A case study of physical activity among older adults in rural Newfoundland, Canada. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2007, 15, 166–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clément, A.; Djilas, D.; Vinet, T.; Aubin, A.; Demers, K.; Levasseur, M. Identification and feasibility of social participation initiatives reducing isolation and involving rural older Canadians in the development of their community. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2018, 30, 845–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Söderhamn, U.; Bjørg, D.; Söderhamn, O. Narrated lived experiences of self-care and health among rural-living older persons with a strong sense of coherence. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2011, 4, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozanova, J.; Dosman, D.; de Jong Gierveld, J. Participation in rural contexts: Community matters. In Rural Ageing: A Good Place to Grow Old? Keating, N., Ed.; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2008; pp. 75–86. [Google Scholar]

- Eales, J.; Keefe, J.; Keating, N. Age-friendly communities. In Rural Ageing: A Good Place to Grow Old? Keating, N., Ed.; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2008; pp. 109–120. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, V.F.; Lavoie, J.; Rose, D. Revisiting the role of neighbourhood change in social exclusion and inclusion of older people. J. Aging Res. 2012, 2012, 148287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourdieu, P. The forms of capital. In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education; Richardson, J., Ed.; Greenwood: New York, NY, USA, 1986; pp. 241–258. [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie, P. Aging people in aging places: Addressing the needs of older adults in rural Saskatchewan. Rural Soc. Work 2001, 6, 74–83. [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie, P.; Cloutier-Fisher, D. Home sweet home: Experiences of place for retirement migrants to small-town British Columbia. Rural Soc. Work 2004, 9, 129–136. [Google Scholar]

- Lawton, M.P.; Weisman, G.D.; Sloane, P.; Calkins, M. Assessing environments for older people with chronic illness. J. Ment. Health Aging 1997, 3, 83–100. [Google Scholar]

- Hinck, S. The lived experience of oldest-old rural adults. Qual. Health Res. 2004, 14, 779–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fausset, C.B.; Kelly, A.J.; Rogers, W.A.; Fisk, A.D. Challenges to aging in place: Understanding home maintenance difficulties. J. Hous. Elder. 2011, 25, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fairhall, N.; Sherrington, C.; Kurrle, S.E.; Lord, S.R.; Cameron, I.D. ICF participation restriction is common in frail, community-dwelling older people: An observational cross-sectional study. Physiotherapy 2011, 97, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amegbor, P.M.; Rosenberg, M.W.; Kuuire, V.Z. Does place matter? A multilevel analysis of victimization and satisfaction with personal safety of seniors in Canada. Health Place 2018, 53, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waldbrook, N.; Rosenberg, M.W.; Brual, J. Challenging the myth of apocalyptic aging at the local level of governance in Ontario. Can. Geogr. 2013, 57, 413–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Database | Terms |

|---|---|

| OVID Medline & Summon® Service | A rural and lived experience AND/OR social participation AND aging OR elderly OR elder OR older |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carver, L.F.; Beamish, R.; Phillips, S.P.; Villeneuve, M. A Scoping Review: Social Participation as a Cornerstone of Successful Aging in Place among Rural Older Adults. Geriatrics 2018, 3, 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics3040075

Carver LF, Beamish R, Phillips SP, Villeneuve M. A Scoping Review: Social Participation as a Cornerstone of Successful Aging in Place among Rural Older Adults. Geriatrics. 2018; 3(4):75. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics3040075

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarver, Lisa F., Rob Beamish, Susan P. Phillips, and Michelle Villeneuve. 2018. "A Scoping Review: Social Participation as a Cornerstone of Successful Aging in Place among Rural Older Adults" Geriatrics 3, no. 4: 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics3040075

APA StyleCarver, L. F., Beamish, R., Phillips, S. P., & Villeneuve, M. (2018). A Scoping Review: Social Participation as a Cornerstone of Successful Aging in Place among Rural Older Adults. Geriatrics, 3(4), 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics3040075