Prevalence and Associated Factors of Depression Among Elderly Hypertensive Patients in Vietnam

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

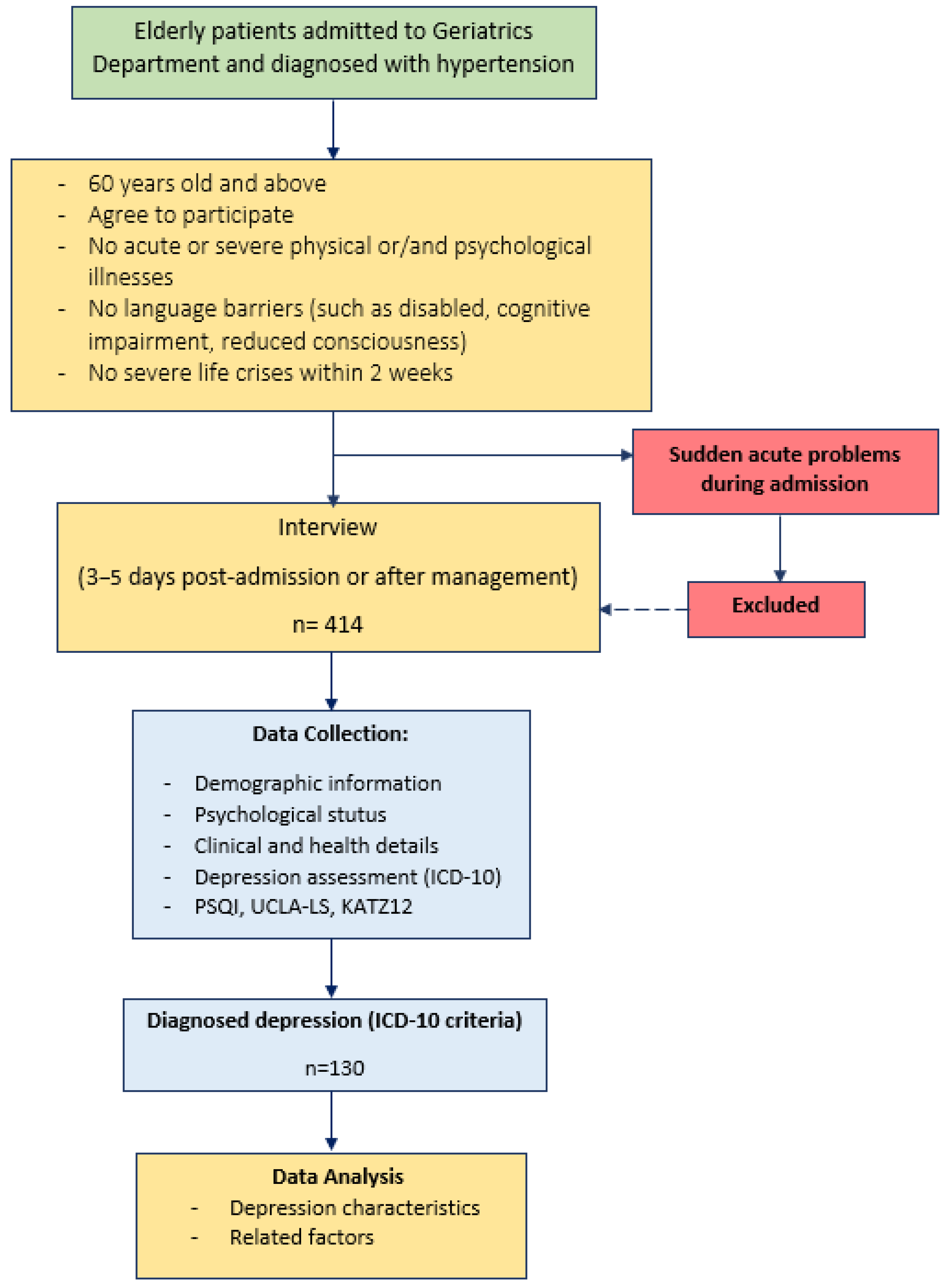

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Data Collection Process

2.3. Variables and Measures

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Research Ethics

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Research Population

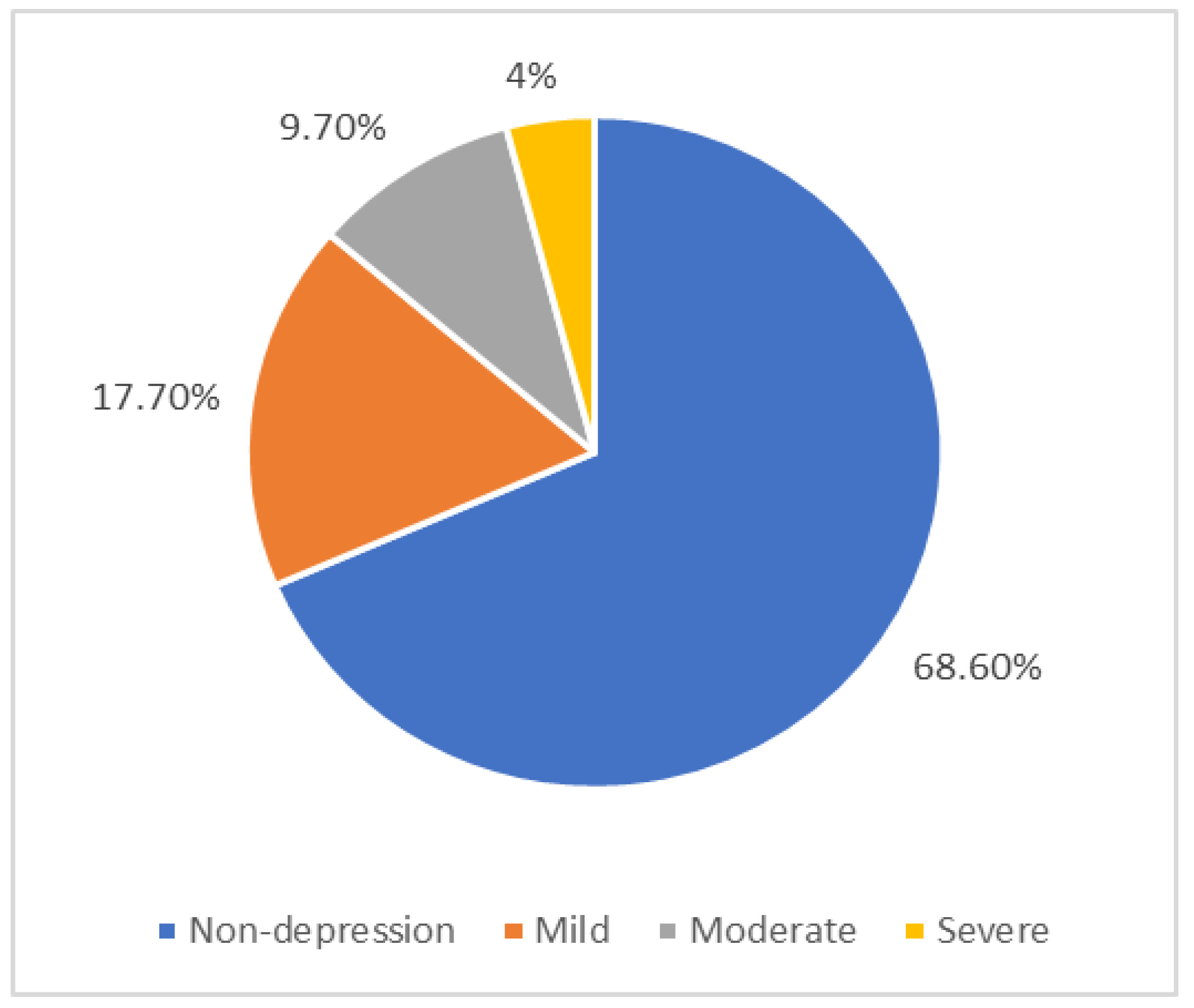

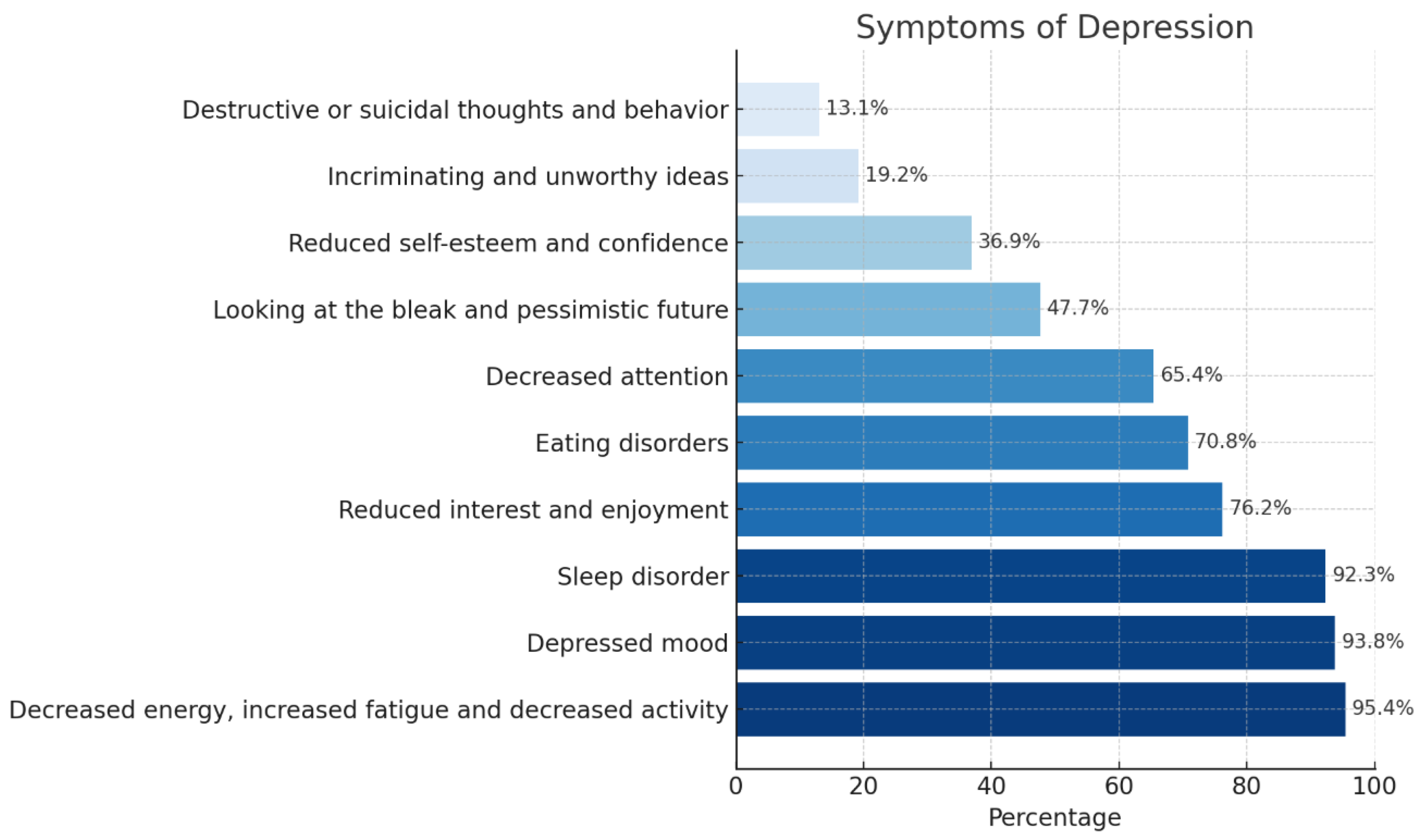

3.2. Prevalence and Characteristics of Depression in Elderly Patients with Hypertension

3.3. Related Factors to Depression in Elderly Patients with Hypertension

4. Discussion

4.1. Prevalence and Characteristics of Depression: Interpretation and Comparison

4.1.1. Prevalence of Depression

4.1.2. Clinical Characteristics of Depression

4.2. Factors Associated with Depression: Analysis and Implications

4.2.1. Sociodemographic Factors

4.2.2. Physical Illnesses and Life Activities Factors

4.3. Limitations and Recommendations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| BMI | Body Max Index |

References

- WHO. Ageing and Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). Ageing. Available online: https://vietnam.unfpa.org/en/topics/ageing-6 (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Sun, X.; Li, X. Editorial: Aging and chronic disease: Public health challenge and education reform. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1175898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Carrillo-Larco, R.M.; Danaei, G.; Riley, L.M.; Paciorek, C.J.; Stevens, G.A.; Gregg, E.W.; Bennett, J.E.; Solomon, B.; Singleton, R.K.; et al. Worldwide trends in hypertension prevalence and progress in treatment and control from 1990 to 2019: A pooled analysis of 1201 population-representative studies with 104 million participants. Lancet 2021, 398, 957–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Mental Health of Older Adults. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-of-older-adults (accessed on 3 October 2024).

- Gan, Q.; Yu, R.; Lian, Z.; Yuan, Y.; Li, Y.; Zheng, L. Unraveling the link between hypertension and depression in older adults: A meta-analysis. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1302341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uomoto, K.E. Increasing Identification and Follow-Up of Older Adult Depression in Primary Care. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2023, 14, 21501319231152758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, C.E.; Valkanova, V.; Ebmeier, K.P. Depression in older people is underdiagnosed. Practitioner 2014, 258, 19–22, 12–13. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Blazer, D.G. Depression in late life: Review and commentary. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2003, 58, 249–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.; Meng, F.; Qi, Y.; Yan, X.; Qi, J.; Wu, Y.; Lin, Y.; Chen, X.; He, F. Association of hypertension and depression with mortality: An exploratory study with interaction and mediation models. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, W.; Xu, L. Pathways linking relative deprivation to blood pressure control: The mediating role of depression and medication adherence among Chinese middle-aged and older hypertensive patients. BMC Geriatr. 2023, 23, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, Q.; Fan, L.; Wang, Z.W.; Li, J. 2023 Guideline for the management of hypertension in the elderly population in China. J. Geriatr. Cardiol. 2024, 21, 589–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.T.; Nguyen, T.; Bui, T.D.; Giang, L.T. Depression and associated factors among older people in Vietnam: Findings from a National Aging Survey. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0299791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang Lan, N.; Thi Thu Thuy, N. Depression among ethnic minority elderly in the Central Highlands, Vietnam. Health Psychol. Open 2020, 7, 2055102920967236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, T.T.H.; Nguyen, D.T.M.; Nguyen, L.T. Depressive Symptoms and Their Correlates Among Older People in Rural Viet Nam: A Study Highlighting the Role of Family Factors. Health Serv. Insights 2022, 15, 11786329221125410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, T.; Ishine, M.; Sakagami, T.; Kita, T.; Okumiya, K.; Mizuno, K.; Rambo, T.A.; Matsubayashi, K. Depression, activities of daily living, and quality of life of community-dwelling elderly in three Asian countries: Indonesia, Vietnam, and Japan. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2005, 41, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Diseases of the circulatory system. In International Classification of Diseases, 10th ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, C.; Chen, S.; Shen, J.; Zheng, X.; Wang, L.; Guan, L.; Liu, Q.; Yang, Y. Prevalence and associated factors of depressive symptoms among elderly inpatients of a Chinese tertiary hospital. Clin. Interv. Aging 2018, 13, 1755–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Van Minh, H.; Tran, H.; Khai, P.; Phuoc, D.; Lan, V.; Vinh, P.; Do Doan, L.; Chau, H.; Tri, N.; Binh, T.; et al. 2018 VNHA/VSH Guidelines for Diagnosis and Treatment of Hypertension in Adults. J. Vietnam. Stud. 2018, 6–7. [Google Scholar]

- Buysse, D.J.; Reynolds, C.F., 3rd; Monk, T.H.; Berman, S.R.; Kupfer, D.J. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989, 28, 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arimoto, A.; Tadaka, E. Reliability and validity of Japanese versions of the UCLA loneliness scale version 3 for use among mothers with infants and toddlers: A cross-sectional study. BMC Womens Health 2019, 19, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, S.; Akpom, C.A. A measure of primary sociobiological functions. Int. J. Health Serv. 1976, 6, 493–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do Van, D.; Doan, K.V.D.; Hang, T.N.M. Prevalence of depression and associated factors among elderly in Truong Quang Trong Ward, Quang Ngai City. Hue J. Med. Pharm. 2018, 8, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Jin, Y.; Liu, R.; Zhang, Q.; Su, Z.; Ungvari, G.S.; Tang, Y.-L.; Ng, C.H.; Li, X.-H.; Xiang, Y.-T. Global prevalence of depression in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological surveys. Asian J. Psychiatry 2023, 80, 103417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamrah, M.S.; Hamrah, M.H.; Ishii, H.; Suzuki, S.; Hamrah, M.H.; Hamrah, A.E.; Dahi, A.E.; Takeshita, K.; Yisireyili, M.; Hamrah, M.H.; et al. Anxiety and Depression among Hypertensive Outpatients in Afghanistan: A Cross-Sectional Study in Andkhoy City. Int. J. Hypertens. 2018, 2018, 8560835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hai, L.S.; Loan, K.X. Depression and associated factors in elderly people in tan hung commune, dong phu district, binh phuoc province in 2019. Ho Chi Minh City J. Med. 2020, 24, 55–63. [Google Scholar]

- Nam, N.B.; Duy, T.H.; Dat, N.T.; Thanh, T.N.; Bay, N.T. Depression and its related factors among hypertensive patients in Can Tho City from 2018 to 2019. Tạp Chí Y Học Dự Phòng 2021, 31, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prina, A.M.; Cosco, T.D.; Dening, T.; Beekman, A.; Brayne, C.; Huisman, M. The association between depressive symptoms in the community, non-psychiatric hospital admission and hospital outcomes: A systematic review. J. Psychosom. Res. 2015, 78, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreadis, E.A. Hypertension: A Growing Threat. In Hypertension and Cardiovascular Disease; Andreadis, E.A., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, H.; Jorm, A.F.; Mackinnon, A.J.; Korten, A.E.; Jacomb, P.A.; Henderson, A.S.; Rodgers, B. Age differences in depression and anxiety symptoms: A structural equation modelling analysis of data from a general population sample. Psychol. Med. 1999, 29, 325–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fok, M.; Stewart, R.; Besset, A.; Ritchie, K.; Prince, M. Incidence and persistence of sleep complaints in a community older population. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2010, 25, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.J.; Son, S.J.; Lee, Y.; Back, J.H.; Lee, K.S.; Lee, S.J.; Chung, Y.K.; Lim, K.Y.; Noh, J.S.; Kim, H.C.; et al. Perceived sleep quality is associated with depression in a Korean elderly population. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2014, 59, 468–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, S.; Malhotra, N. Depression in elderly: A review of Indian research. J. Geriatr. Ment. Health 2015, 2, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, M.G.; Dendukuri, N. Risk factors for depression among elderly community subjects: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Psychiatry 2003, 160, 1147–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, S.; Hassan, S.Z.; Tabraze, M.; Khan, M.O.; Javed, I.; Ahmed, A.; Siddiqui, O.M.; Narmeen, M.; Ahmed, M.J.; Tariq, A.; et al. Prevalence and Predictors of Depression Amongst Hypertensive Individuals in Karachi, Pakistan. Cureus 2017, 9, e1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Depressive Disorder (Depression). Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression (accessed on 21 October 2024).

- Simonson, J.; Mezulis, A.; Davis, K. Socialized to Ruminate? Gender Role Mediates the Sex Difference in Rumination for Interpersonal Events. J. Social. Clin. Psychol. 2011, 30, 937–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, J.; Carrière, I.; Scali, J.; Ritchie, K.; Ancelin, M.L. Lifetime hormonal factors may predict late-life depression in women. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2008, 20, 1203–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashok, V.G.; Ghosh, S.S. Prevalence of Depression among Hypertensive Patients Attending a Rural Health Centre in Kanyakumari. Natl. J. Community Med. 2019, 10, 172–175. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, C.; Miao, L.; Turner, D.; DeRubeis, R. Urbanicity and depression: A global meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 340, 299–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, J.A.; Kim, S.A.; Yang, J.H.; Shin, M.H. Urban-Rural Differences in the Prevalence of Depressive Symptoms in Korean Adults. Chonnam Med. J. 2023, 59, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purtle, J.; Nelson, K.L.; Yang, Y.; Langellier, B.; Stankov, I.; Diez Roux, A.V. Urban–Rural Differences in Older Adult Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Comparative Studies. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2019, 56, 603–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabañero-Garcia, E.; Martinez-Lacoba, R.; Pardo-Garcia, I.; Amo-Saus, E. Barriers to health, social and long-term care access among older adults: A systematic review of reviews. Int. J. Equity Health 2025, 24, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkley, L.C.; Thisted, R.A.; Masi, C.M.; Cacioppo, J.T. Loneliness predicts increased blood pressure: 5-year cross-lagged analyses in middle-aged and older adults. Psychol. Aging 2010, 25, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mermerelis, A.; Kyvelou, S.M.; Vellinga, A.; Stefanadis, C.; Papageorgiou, C.; Douzenis, A. Anxiety and Depression Prevalence in Essential Hypertensive Patients is there an Association with Arterial Stiffness? J. Depress. Anxiety 2018, 7, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, D.J.; Lichstein, K.L.; Durrence, H.H.; Reidel, B.W.; Bush, A.J. Epidemiology of Insomnia, Depression, and Anxiety. Sleep. 2005, 28, 1457–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Tu, S.; Sheng, J.; Shao, A. Depression in sleep disturbance: A review on a bidirectional relationship, mechanisms and treatment. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2019, 23, 2324–2332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Yu, C.; Huang, K.; Thomas, S.; Yang, W.; Liu, S.; Kuang, J. The Association between Hypertension and Insomnia: A Bidirectional Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. Int. J. Hypertens. 2022, 2022, 4476905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-Aceituno, A.; Guallar-Castillón, P.; García-Esquinas, E.; Rodríguez-Artalejo, F.; Banegas, J.R. Association between sleep characteristics and antihypertensive treatment in older adults. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2019, 19, 537–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | Frequency (n) | Ratio (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Youngest: 60, Oldest: 101 Mean: 74.92 (Standard deviation: 8.35 years old) | ||

| Sex | Female | 285 | 68.8 |

| Male | 129 | 31.2 | |

| Level Education | Below high school | 372 | 89.9 |

| High school and higher | 42 | 10.1 | |

| Status marriage | Single/divorced/separated/lost spouse | 147 | 35.5 |

| Have a spouse living together | 267 | 64.5 | |

| Economy society | Poor | 30 | 7.2 |

| Not poor | 384 | 92.8 | |

| Living area | Rural areas | 303 | 73.2 |

| Urban areas | 111 | 26.8 | |

| BMI | Underweight | 49 | 11.8 |

| Normal | 310 | 74.9 | |

| Overweight—Obesity | 55 | 13.3 | |

| Number of other physical diseases | >2 | 147 | 35.5 |

| 2 and under | 267 | 64.5 | |

| Grade of hypertension | Grade 1 | 141 | 34.1 |

| Grade 2 | 140 | 33.8 | |

| Grade 3 and Isolated systolic hypertension | 133 | 32.1 | |

| Hypertension complication | Have | 123 | 29.7 |

| None | 291 | 70.3 | |

| Factor | Category/Unit | Depressed n/N (%) | Unadjusted p | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male vs. Female (ref) | 20/129 (15.5) vs. 110/285 (38.6) | <0.001 (χ2) | 0.35 (0.18–0.68) | 0.002 |

| Socioeconomic status (SES) | Not-poor vs. Poor (ref) | 111/384 (28.9) vs. 19/30 (63.3) | <0.001 (χ2) | 0.33 (0.12–0.91) | 0.032 |

| Living area | Urban vs. Rural (ref) | 29/111 (26.1) vs. 101/303 (33.3) | 0.162 (χ2) | 0.69 (0.36–1.31) | 0.256 |

| Comorbidities | ≤2 vs. >2 (ref) | 83/291 (28.5) vs. 47/123 (38.2) | 0.052 (χ2) | 0.72 (0.40–1.30) | 0.278 |

| Hypertension stage | 2 vs. 1 (ref) | 49/140 (35.0) vs. 33/141 (23.4) | 0.041 (χ2) | 2.02 (1.03–3.96) | 0.041 |

| 3/ISH vs. 1 (ref) | 48/133 (36.1) vs. 33/141 (23.4) | — | 2.38 (1.20–4.73) | 0.014 | |

| Physical activity | Medium vs. Low (ref) | 38/200 (19.0) vs. 90/200 (45.3) | <0.001 (χ2) | 0.61 (0.33–1.10) | 0.099 |

| High vs. Low (ref) | 1/13 (7.7) vs. 90/200 (45.3) | — | 0.89 (0.08–9.51) | 0.926 | |

| PSQI | per 1-point increase | mean 12.7 ± 4.2 vs. 8.4 ± 4.0 | <0.001 (Mann–Whitney U) | 1.22 (1.14–1.31) | <0.001 |

| UCLA-LS3-J11 | per 1-point increase | mean 43.0 ± 12.3 vs. 31.0 ± 9.4 | <0.001 (Mann–Whitney U) | 1.07 (1.05–1.10) | <0.001 |

| Katz | per 1-point increase | mean 4.65 ± 1.91 vs. 5.38 ± 1.40 | <0.001 (Mann–Whitney U) | 0.92 (0.78–1.09) | 0.325 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nguyen, T.V.; Vu, T.S.; Tran, T.T.; Nguyen, T.T.; Le, H.M.; Nguyen, T.; To Tran, K.A.; Tran, C.M.; Nguyen, T.V. Prevalence and Associated Factors of Depression Among Elderly Hypertensive Patients in Vietnam. Geriatrics 2025, 10, 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics10050129

Nguyen TV, Vu TS, Tran TT, Nguyen TT, Le HM, Nguyen T, To Tran KA, Tran CM, Nguyen TV. Prevalence and Associated Factors of Depression Among Elderly Hypertensive Patients in Vietnam. Geriatrics. 2025; 10(5):129. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics10050129

Chicago/Turabian StyleNguyen, Tuan Van, Tung Son Vu, Thang Thien Tran, Thong Thai Nguyen, Hoang Minh Le, Thang Nguyen, Kha Ai To Tran, Chau Minh Tran, and Thong Van Nguyen. 2025. "Prevalence and Associated Factors of Depression Among Elderly Hypertensive Patients in Vietnam" Geriatrics 10, no. 5: 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics10050129

APA StyleNguyen, T. V., Vu, T. S., Tran, T. T., Nguyen, T. T., Le, H. M., Nguyen, T., To Tran, K. A., Tran, C. M., & Nguyen, T. V. (2025). Prevalence and Associated Factors of Depression Among Elderly Hypertensive Patients in Vietnam. Geriatrics, 10(5), 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics10050129