A Systematic Review on Subjective Cognitive Complaints: Main Neurocognitive Domains, Myriad Assessment Tools, and New Approaches for Early Detection

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Systematic Search (Databases, Descriptors, Search Formulas)

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

- -

- Empirical research on neuropsychological tools used in the study of subjective cognitive complaints.

- -

- Studies published in the last 15 years with a population aged 60 or older with subjective cognitive complaints.

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

- -

- Studies addressing neuropsychological tests for subjective cognitive complaints in other clinical contexts (pathologies or neurologic/psychiatric diseases that may also involve SCC).

- -

- Research exploring neuropsychological assessments in mild cognitive impairment and advanced stages of dementia.

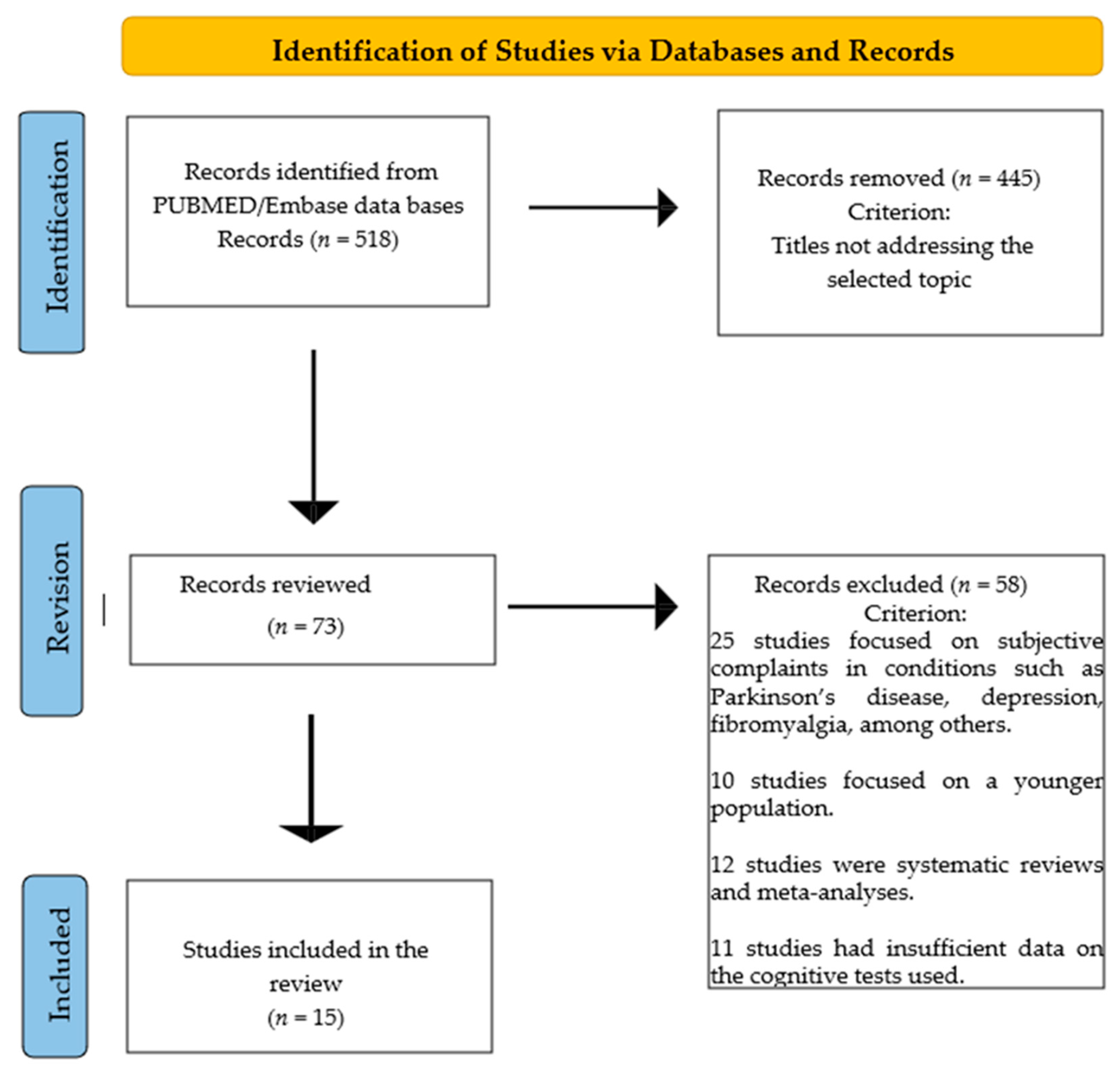

2.4. Flow Chart

3. Results

3.1. Most Relevant Data from the Studies Included in This Review

3.2. Participants and Sociodemographic Variables

3.3. Neuropsychological Domains

3.4. Neuropsychological Tests

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jessen, F.; Amariglio, R.E.; Buckley, R.F.; van der Flier, W.M.; Han, Y.; Molinuevo, J.L.; Rabin, L.; Rentz, D.M.; Rodriguez-Gomez, O.; Saykin, A.J.; et al. The characterization of subjective cognitive decline. Lancet Neurol. 2020, 19, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liew, T.M. Subjective cognitive decline, anxiety symptoms, and the risk of mild cognitive impairment and dementia. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 2020, 12, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessen, F. Subjective and objective cognitive decline at the pre-dementia stage of Alzheimer’s disease. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2014, 264, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, A.J.; Beaumont, H.; Ferguson, D.; Yadegarfar, M.; Stubbs, B. Risk of dementia and mild cognitive impairment in older people with subjective memory complaints: Meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2014, 130, 439–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albert, M.S.; Moss, M.B.; Tanzi, R.; Jones, K. Preclinical prediction of AD using neuropsychological tests. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2001, 7, 631–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begali, V.L. Neuropsychology and the dementia spectrum: Differential diagnosis, clinical management, and forensic utility. NeuroRehabilitation 2020, 46, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzola, P.; Carnero, C.; Bermejo-Pareja, F.; Sánchez-Benavides, G.; Peña-Casanova, J.; Puertas-Martín, V.; Fernández-Calvo, B.; Contador, I. Neuropsychological Assessment for Early Detection and Diagnosis of Dementia: Current Knowledge and New Insights. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 3442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weintraub, S. Neuropsychological Assessment in Dementia Diagnosis. Continuum 2022, 28, 781–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watermeyer, T.; Calia, C. Neuropsychological assessment in preclinical and prodromal Alzheimer disease: A global perspective. J. Glob. Health 2019, 9, 010317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Harten, A.C.; Smits, L.L.; Teunissen, C.E.; Visser, P.J.; Koene, T.; Blankenstein, M.A.; Scheltens, P.; van der Flier, W.M. Preclinical AD predicts decline in memory and executive functions in subjective complaints. Neurology 2013, 81, 1409–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledo, J.B.; Bjerke, M.; Chen, K.; Rozycki, M.; Jack, C.R.; Weiner, M.W.; Arnold, S.E.; Reiman, E.M.; Davatzikos, C.; Shaw, L.M.; et al. Memory, executive, and multidomain subtle cognitive impairment. Neurology 2015, 85, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, E.H.; Kim, H.; Lee, K.H.; Choo, I.H. Altered Executive Function in Pre-Mild Cognitive Impairment. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2016, 54, 933–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verfaillie, S.C.J.; Slot, R.E.; Tijms, B.M.; Bouwman, F.; Benedictus, M.R.; Overbeek, J.M.; Koene, T.; Vrenken, H.; Scheltens, P.; Barkhof, F.; et al. Thinner cortex in patients with subjective cognitive decline is associated with steeper decline of memory. Neurobiol. Aging 2018, 61, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, J.; Kim, W.; Kim, B.; Chang, S.; Lee, D.; Cho, M. Associations between subjective memory complaints and executive functions in a community sample of elderly without cognitive dysfunction. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2017, 13, 1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viviano, R.P.; Hayes, J.M.; Pruitt, P.J.; Fernandez, Z.J.; van Rooden, S.; van der Grond, J.; Rombouts, S.; Damoiseaux, J.S. Aberrant memory system connectivity and working memory performance in subjective cognitive decline. Neuroimage 2019, 15, 556–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valech, N.; Tort-Merino, A.; Coll-Padrós, N.; Olives, J.; León, M.; Rami, L.; Molinuevo, J.L. Executive and Language Subjective Cognitive Decline Complaints Discriminate Preclinical Alzheimer’s Disease from Normal Aging. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2018, 61, 689–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Cordón, A.; Monté-Rubio, G.; Sanabria, A.; Rodriguez-Gomez, O.; Valero, S.; Abdelnour, C.; Marquié, M.; Espinosa, A.; Ortega, G.; Hernandez, I.; et al. Subtle executive deficits are associated with higher brain amyloid burden and lower cortical volume in subjective cognitive decline: The FACEHBI cohort. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 17721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.H.; Kim, B.S.; Chang, S.M.; Lee, D.W.; Bae, J.N. Relationship between subjective memory complaint and executive function in a community sample of South Korean elderly. Psychogeriatrics 2020, 20, 850–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, L.; Sun, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Wei, Z.; Gao, G.; Jia, J.; Xing, Y.; et al. Demographic characteristics and neuropsychological assessments of subjective cognitive decline (SCD) (plus). Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2020, 7, 1002–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.C.; Kang, J.M.; Lee, H.; Kim, K.; Kim, S.; Yu, T.Y.; Lee, E.M.; Kim, C.T.; Kim, D.K.; Lewis, M.; et al. Subjective cognitive decline and subsequent dementia: A nationwide cohort study of 579,710 people aged 66 years in South Korea. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 2020, 12, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Numbers, K.; Lam, B.C.P.; Crawford, J.D.; Kochan, N.A.; Sachdev, P.S.; Brodaty, H. Increased reporting of subjective cognitive complaints over time predicts cognitive decline and incident dementia. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2021, 36, 1739–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrido-Chaves, R.; Perez, V.; Perez-Alarcón, M.; Crespo-Sanmiguel, I.; Paiva, T.O.; Hidalgo, V.; Pulopulos, M.M.; Salvador, A. Subjective MemoryComplaints and Decision Making in Young and Older Adults: An Event-Related Potential Study. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021, 13, 695275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, M.D.; Morrison, C.; Kamal, F.; Graham, J.; Dadar, M. Subjective cognitive decline is a better marker for future cognitive decline in females than in males. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 2022, 14, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrison, C.; Dadar, M.; Shafiee, N.; Villeneuve, S.; Louis Collins, D.; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Regional brain atrophy and cognitive decline depend on definition of subjective cognitive decline. Neuroimage Clin. 2022, 33, 102923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yates, J.A.; Clare, L.; Woods, R.T.; MRC CFAS. Subjective memory complaints, mood and MCI: A follow-up study. Aging Ment. Health 2017, 21, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breton, A.; Casey, D.; Arnaoutoglou, N.A. Cognitive tests for the detection of mild cognitive impairment (MCI), the prodromal stage of dementia: Meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy studies. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2019, 34, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, T.; Ferreira, F.L.; Cardoso, S.; Silva, D.; de Mendonça, A.; Guerreiro, M.; Madeira, S.C.; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Neuropsychological predictors of conversion from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease: A feature selection ensemble combining stability and predictability. BMC Med. Inf. Decis. Mak. 2018, 18, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, T.C.C.; Machado, L.; Bulgacov, T.M.; Rodrigues-Júnior, A.L.; Costa, M.L.G.; Ximenes, R.C.C.; Sougey, E.B. Is the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) screening superior to the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) in the detection of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) in the elderly? Int. Psychogeriatr. 2019, 31, 491–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jongsiriyanyong, S.; Limpawattana, P. Mild Cognitive Impairment in Clinical Practice: A Review Article. Am. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. Other Demen 2018, 33, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kueper, J.K.; Speechley, M.; Montero-Odasso, M. The Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive Subscale (ADAS-Cog): Modifications and Responsiveness in Pre-Dementia Populations. A Narrative Review. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2018, 63, 423–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oghabon, E.K.; Giménez-Llort, L. Short height and poor education increase the risk of dementia in Nigerian type 2 diabetic women. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2019, 11, 493–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, L.; Yang, Y.; Gao, J. Cognitive assessment tools for mild cognitive impairment screening. J. Neurol. 2021, 268, 1615–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gainotti, G.; Quaranta, D.; Vita, M.G.; Marra, C. Neuropsychological predictors of conversion from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2014, 38, 481–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.L.; de Vasconcelos, T.H.F.; de Oliveira, A.A.R.; Campagnolo, S.B.; Figueiredo, S.O.; Guimarães, A.F.B.C.; Barbosa, M.T.; de Miranda, L.F.J.R.; Caramelli, P.; de Souza, L.C. Memory complaints at primary care in a middle-income country: Clinical and neuropsychological characterization. Dement. Neuropsychol. 2021, 15, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folia, V.; Liampas, I.; Siokas, V.; Silva, S.; Ntanasi, E.; Yannakoulia, M.; Sakka, P.; Hadjigeorgiou, G.; Scarmeas, N.; Dardiotis, E.; et al. Language performance as a prognostic factor for developing Alzheimer’s clinical syndrome and mild cognitive impairment: Results from the population-based HELIAD cohort. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2023, 29, 450–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macoir, J.; Tremblay, P.; Hudon, C. The Use of Executive Fluency Tasks to Detect Cognitive Impairment in Individuals with Subjective Cognitive Decline. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allain, P.; Etcharry-Bouyx, F.; Verny, C. Executive functions in clinical and preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Rev. Neurol. 2013, 169, 695–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster-Cordero, F.; Giménez-Llort, L. The Challenge of Subjective Cognitive Complaints and Executive Functions in Middle-Aged Adults as a Preclinical Stage of Dementia: A Systematic Review. Geriatrics 2022, 7, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, R.; Whitfield, T.; Said, G.; John, A.; Saunders, R.; Marchant, N.L.; Stott, J.; Charlesworth, G. Affective symptoms and risk of progression to mild cognitive impairment or dementia in subjective cognitive decline: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 2021, 71, 101419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liew, T.M. Depression, subjective cognitive decline, and the risk of neurocognitive disorders. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 2019, 11, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isella, V.; Villa, L.; Russo, A.; Regazzoni, R.; Ferrarese, C.; Appollonio, I.M. Discriminative and predictive power of an informant report in mild cognitive impairment. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2006, 77, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Almeida, M.L.; Dalpubel, D.; Ribeiro, E.B.; de Oliveira, E.S.B.; Ansai, J.H.; Vale, F.A.C. Subjective cognitive impairment, cognitive disorders and self-perceived health: The importance of the informant. Dement. Neuropsychol. 2019, 13, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farfel, J.M.; Barnes, L.L.; Capuano, A.; Sampaio, M.C.M.; Wilson, R.S.; Bennett, D.A. Informant-Reported Discrimination, Dementia, and Cognitive Impairment in Older Brazilians. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2021, 84, 973–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caselli, R.J.; Langlais, B.T.; Dueck, A.C.; Henslin, B.R.; Johnson, T.A.; Woodruff, B.K.; Hoffman-Snyder, C.; Locke, D.E.C. Personality Changes During the Transition from Cognitive Health to Mild Cognitive Impairment. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2018, 66, 671–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terracciano, A.; Luchetti, M.; Stephan, Y.; Löckenhoff, C.E.; Ledermann, T.; Sutin, A.R. Changes in Personality Before and During Cognitive Impairment. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2023, 24, 1465–1470.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzen, S.; van den Berg, E.; Goudsmit, M.; Jurgens, C.K.; van de Wiel, L.; Kalkisim, Y.; Uysal-Bozkir, Ö.; Ayhan, Y.; Nielsen, T.R.; Papma, J.M. A Systematic Review of Neuropsychological Tests for the Assessment of Dementia in Non-Western, Low-Educated or Illiterate Populations. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2020, 26, 331–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, T.R. Cognitive Assessment in Culturally, Linguistically, and Educationally Diverse Older Populations in Europe. Am. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. Other Demen 2022, 37, 15333175221117006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, C.T.; Seward, K.; Patterson, A.; Melton, A.; MacDonald-Wicks, L. Evaluation of Available Cognitive Tools Used to Measure Mild Cognitive Decline: A Scoping Review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vostrý, M.; Zilcher, L. The use of rehabilitation therapy with the participation of people with different types of neurological disease from the perspective of helping professions. In Proceedings of the 12th annual International Conference of Education, Research and Innovation, Seville, Spain, 11–13 November 2019; pp. 104–109. [Google Scholar]

| Authors [Reference] Country | Sample Subjects’ Diagnosis (Gender Ratio) [Mean Age] {Mean Years of Education} | Domains Assessed | Tests Used |

|---|---|---|---|

| van Harten et al. [11] The Netherlands | 132 participants with SCC (56 W:76 M) [61.4] {6} | Screening scales Depression/anxiety scales Intelligence Praxis Language Visual perception Visuospatial Executive function Memory Self/Informant report | MMSE - - - Semantic fluency - - TMT A-B, DST VAT, RAVLT - |

| Toledo et al. [12] USA | 522 participants (253 W:269 M): 307 CN subjects (138 W:169 M) [73.9] {-} 71 subjects SCC (25 W:46 M) [71.6] {-} 51 subjects executive SCI (21 W:30 M) [77.3] {-} 66 subjects memory SCI (49 W:17 M) [75] {-} 27 subjects multi-domain SCI (20 W:7 M) [78] {-} | Screening scales Depression/anxiety scales Intelligence Praxis Language Visual perception Visuospatial Executive function Memory Self/Informant report | MMSE, ADAS - - - - - - - - - |

| Seo et al. [13] Korea | 265 participants (178 W:79 M): 188 CN subjects (120 W:60 M) [71.94] {9.69} 77 subjects pre-DCL (58 W:19 M) [72.64] {9.64} | Screening scales Depression/anxiety scales Intelligence Praxis Language Visual perception Visuospatial Executive function Memory Self/Informant report | MMSE, SNSB GDS - RCFT CPFT, K-BNT - RCFT TMT A-B, DST, Stroop test, SVLT SMCQ (informant report) |

| Verfaillie et al. [14] The Netherlands | 233 participants SCD (107 W: 125 M) [62.82] {5.32} | Screening scales Depression/anxiety scales Intelligence Praxis Language Visual perception Visuospatial Executive function Memory Self/Informant report | MMSE GDS - - Semantic fluency - - TMT A-B, DST, Stroop test RAVLT, VAT - |

| Bae et al. [15] South Korea | 1442 participants (-) [-] {-}: 1088 HC subjects (-) [-] {-} 354 SCC (-) [-] {-} | Screening scales Depression/anxiety scales Intelligence Praxis Language Visual perception Visuospatial Executive function Memory Self/Informant report | MMSE - - - - - - K-DRS (Inhibition/Perseveration) - - |

| Viviano et al. [16] USA, The Netherlands | 83 participants (51 W:32 M): 35 adults with SCI (22 W:13 M) [68.5] {-} 48 adults without SCI (29 W:19 M) [67.08] {-} | Screening scales Depression/anxiety scales Intelligence Praxis Language Visual perception Visuospatial Executive function Memory Self/Informant report | MMSE, BFI GDS, BDI - - - - - - WMS - |

| Valech et al. [17] Spain | 68 normal subjects (46 W:22 M): 52 HC (33 W:19 M) [63.87] {11.96} 16 pre-AD (13 W and 3 M) [66.5] {9.56} | Screening scales Depression/anxiety scales Intelligence Praxis Language Visual perception Visuospatial Executive function Memory Self/Informant report | MMSE HADS - - BNT, BDAE, Semantic fluency VOSP - TMT A, Stroop test MAT, FCSRT-IR SCD-Q |

| Pérez et al. [18] Spain | 195 participants SCD (121 W:74 M) [65.71] {14.94} | Screening scales Depression/anxiety scales Intelligence Praxis Language Visual perception Visuospatial Executive function Memory Self/Informant report | - - WAIS - Semantic fluency, Phonological fluency - - TMT A-B, RSCS-BADS, AI-SKT - - |

| Kim et al. [19] Korea | 1442 participants (886 W:556 M) [≥65 years]: 1088 HC subjects (642 W:446 M) {5.66} 354 SCC subjects (244 W:110 M) {3.33} | Screening scales Depression/anxiety scales Intelligence Praxis Language Visual perception Visuospatial Executive function Memory Self/Informant report | MMSE-KC - - - - - - K-DRS (Inhibition/Perseveration) - - |

| Hao et al. [20] China | 615 subjects SCD plus (378 W:228 M) [-] {-} | Screening scales Depression/anxiety scales Intelligence Praxis Language Visual perception Visuospatial Executive function Memory Self/Informant report | MoCA - - CDT Semantic fluency - - TMT B AVLT-H SCD-Q |

| Lee et al. [21] Korea | 579.710 subjects (313.399 W:266.311 M) [66] {11.6}: 357.654 subjects Non-SCD 222.056 subjects SCD | Screening scales Depression/anxiety scales Intelligence Praxis Language Visual perception Visuospatial Executive function Memory Self/Informant report | - - - - - - - - - (KDSQ-P) |

| Numbers et al. [22] Australia | 873 subjects SCD (480 W:392 M) [78.65] {-} | Screening scales Depression/anxiety scales Intelligence Praxis Language Visual perception Visuospatial Executive function Memory Self/Informant report | - - - - BNT, Semantic fluency, Phonological fluency - Block Design Digit Symbol Coding, TMT A-B, WMS, RAVLT, Benton Visual Test - |

| Garrido et al. [23] Spain | 136 participants (67 W:59 M): 28 young adults with SCC (17 W:11 M) [21] {-} 37 young adults without SCC (16 W:11 M) [23] {-} 32 older adults with SCC (18 W:14 M) [63] {-} 39 older adults without SCC (16 W:23 M) [65] {-} | Screening scales Depression/anxiety scales Intelligence Praxis Language Visual perception Visuospatial Executive function Memory Self/Informant report | MMSE - - RCFT Semantic fluency, Phonological fluency - - TMT A-B, Stroop test, DST, IGT FCSRT MFE-30 |

| Oliver et al. [24] USA | 3019 healthy older adults 831 with SCD (635 W:196 M) 2188 without SCD (1660 W:528 M) [73.6] {14.74} | Screening scales Depression/anxiety scales Intelligence Praxis Language Visual perception Visuospatial Executive function Memory Self/Informant report | - - - - BNT NC PM, Line Orientation DST, SDMT, Stroop test WMSR, EBS, WLMR - |

| Morrison et al. [25] Canada | 273 participants: 97 with SCD (36 W:61 M) 176 without SCD (90 W:86 M) [72.97] {16.66} | Screening scales Depression/anxiety scales Intelligence Praxis Language Visual perception Visuospatial Executive function Memory Self/Informant report | ADAS-13, MMSE, MoCA - - - - - - - - - |

| Domains | Tool | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Screening | MMSE | 10 | 77 |

| Executive function | TMT A-B | 8 | 62 |

| Stroop test | 5 | 38 | |

| DST | 5 | 38 | |

| Language | Semantic and Phonological fluency test | 5 | 38 |

| BNT | 4 | 31 | |

| Memory | RAVLT | 4 | 31 |

| WMS | 3 | 23 | |

| Depression and Anxiety | GDS | 3 | 23 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Webster-Cordero, F.; Giménez-Llort, L. A Systematic Review on Subjective Cognitive Complaints: Main Neurocognitive Domains, Myriad Assessment Tools, and New Approaches for Early Detection. Geriatrics 2025, 10, 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics10030065

Webster-Cordero F, Giménez-Llort L. A Systematic Review on Subjective Cognitive Complaints: Main Neurocognitive Domains, Myriad Assessment Tools, and New Approaches for Early Detection. Geriatrics. 2025; 10(3):65. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics10030065

Chicago/Turabian StyleWebster-Cordero, Felipe, and Lydia Giménez-Llort. 2025. "A Systematic Review on Subjective Cognitive Complaints: Main Neurocognitive Domains, Myriad Assessment Tools, and New Approaches for Early Detection" Geriatrics 10, no. 3: 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics10030065

APA StyleWebster-Cordero, F., & Giménez-Llort, L. (2025). A Systematic Review on Subjective Cognitive Complaints: Main Neurocognitive Domains, Myriad Assessment Tools, and New Approaches for Early Detection. Geriatrics, 10(3), 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics10030065