Genomic Characterization of a Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae Strain from Hu Sheep in Inner Mongolia, China

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Clinical Case Description and Sample Collection

2.2. Histopathological Analysis

2.3. Bacterial Isolation and Culture

2.4. Molecular Identification

2.5. Genomic DNA Extraction and Sequencing

2.6. Genome Assembly and Annotation

2.7. Gene Function Analysis

2.8. Comparative Genomic Analysis

2.9. Analysis of the Microbial Community in Sheep Lung Tissue Samples by 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing

3. Results

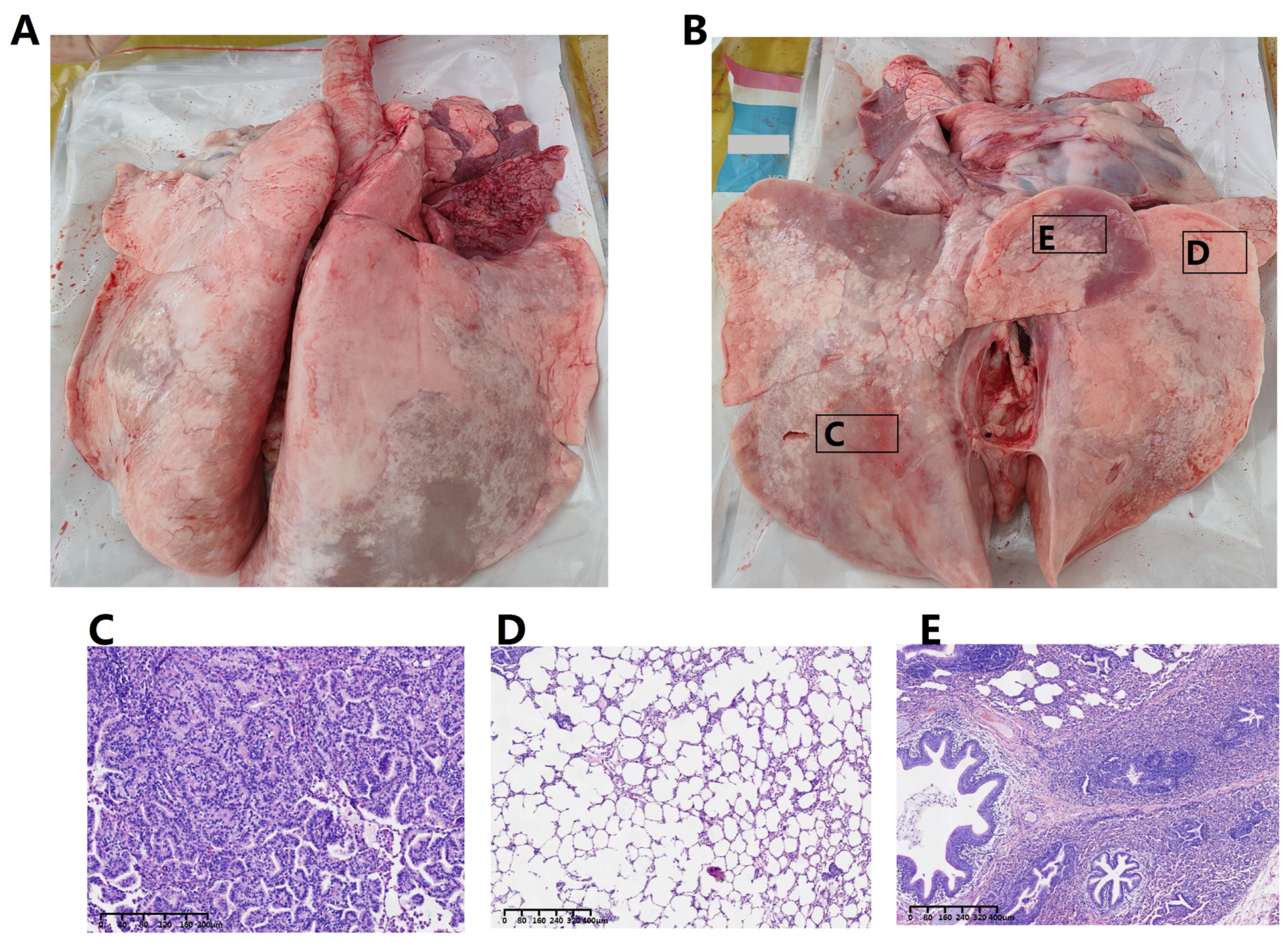

3.1. Pathological Alterations in the Respiratory System

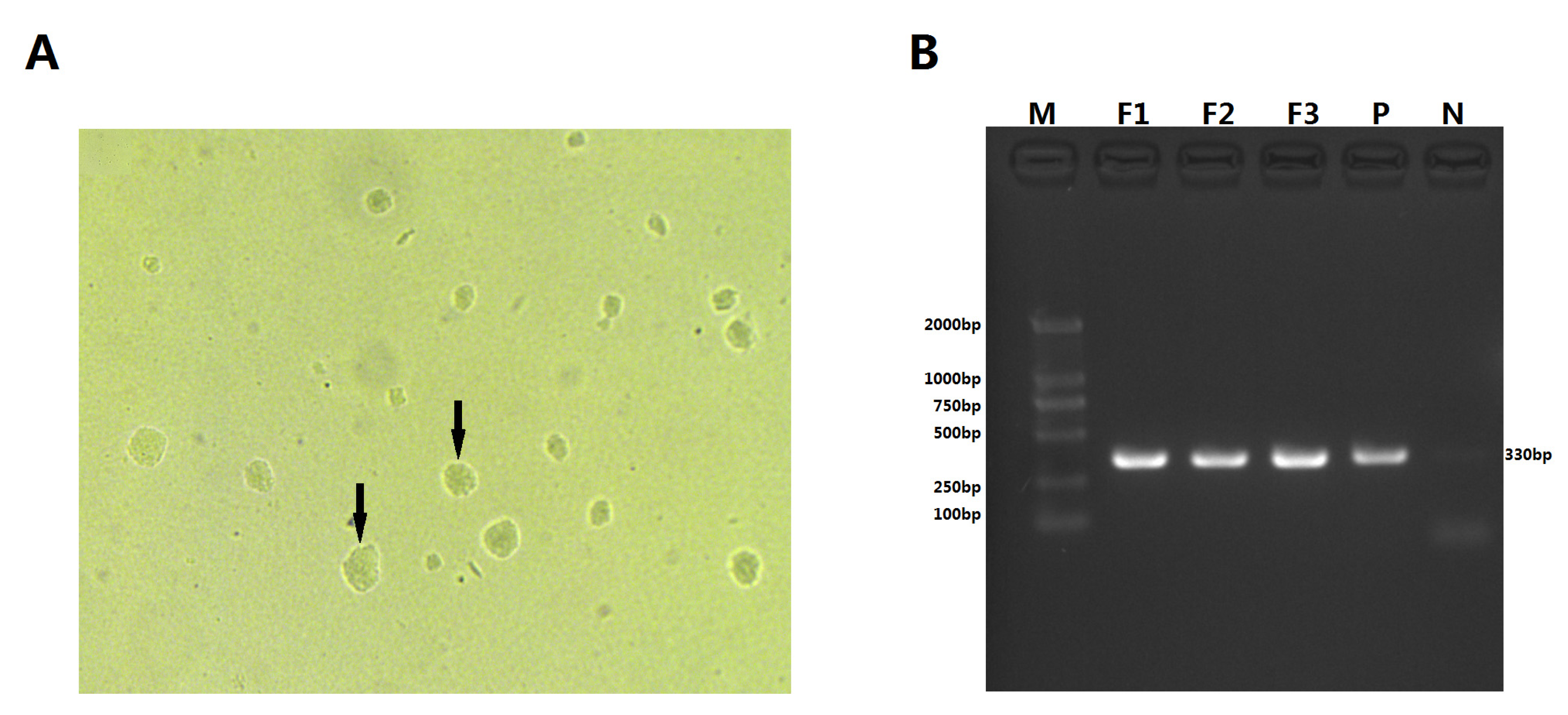

3.2. Isolation and Phenotypic Characterization of M. ovipneumoniae

3.3. Genomic Characteristics of M. ovipneumoniae Strain IM-DMQ

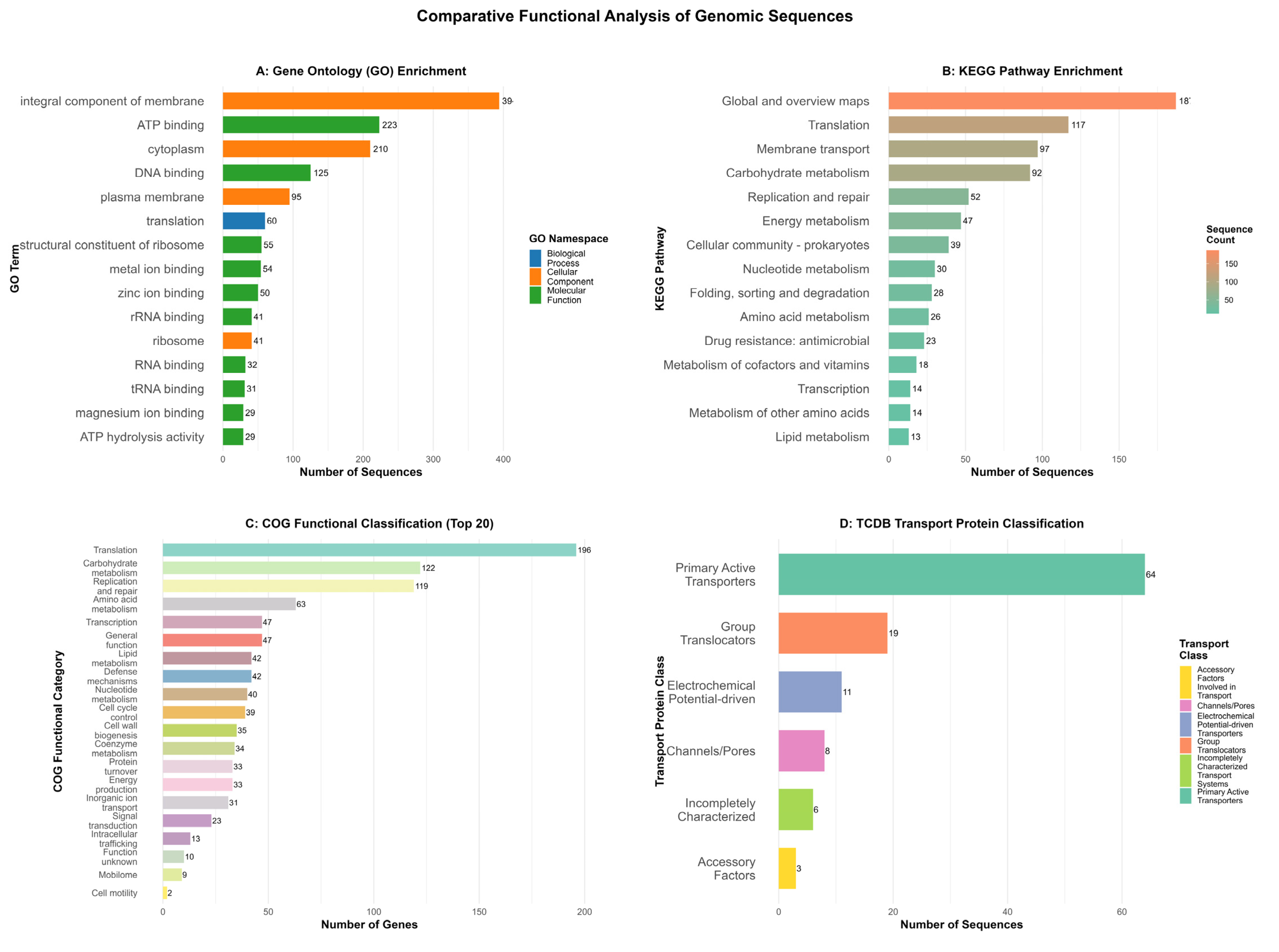

3.4. Functional Genomic Characterization

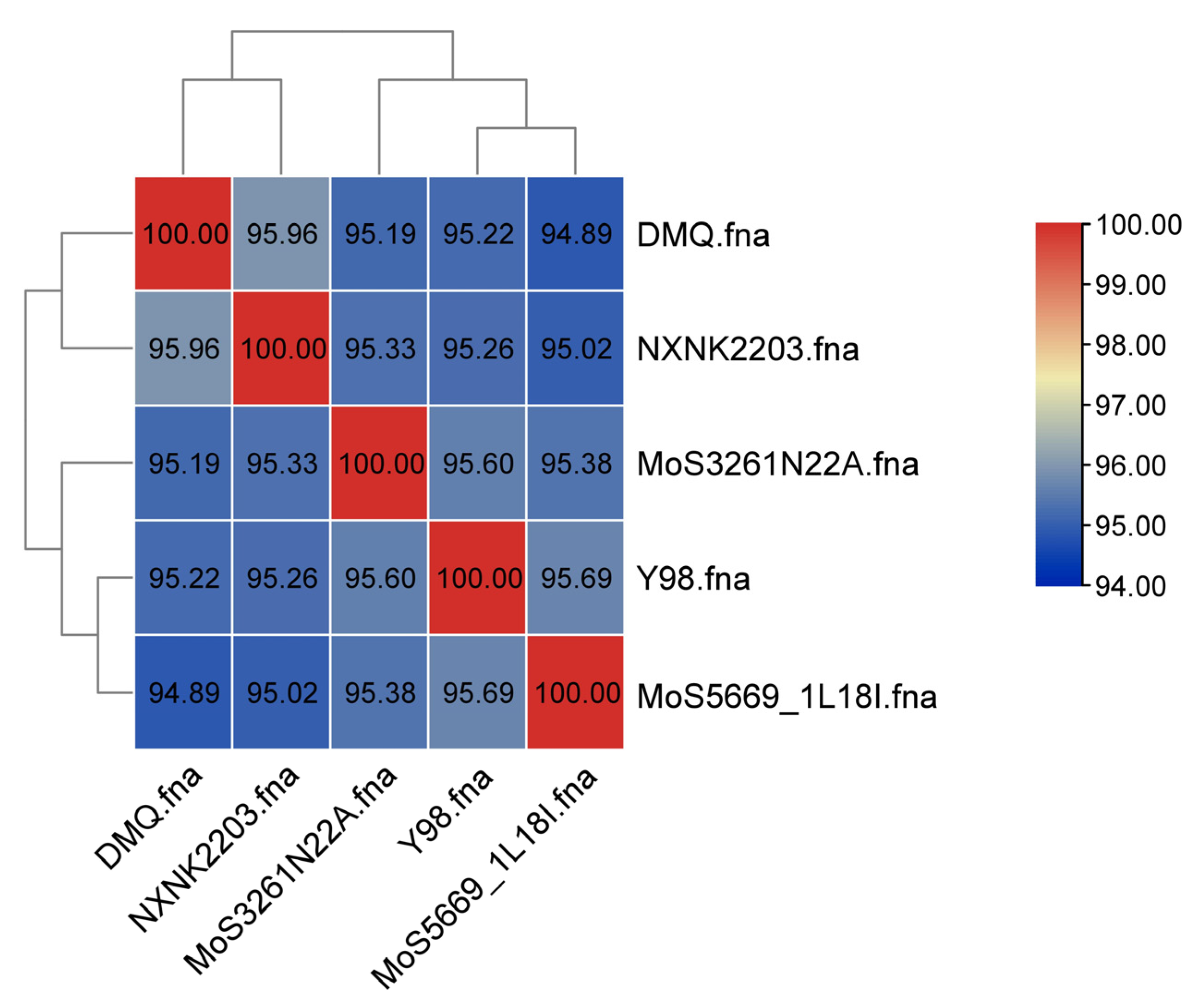

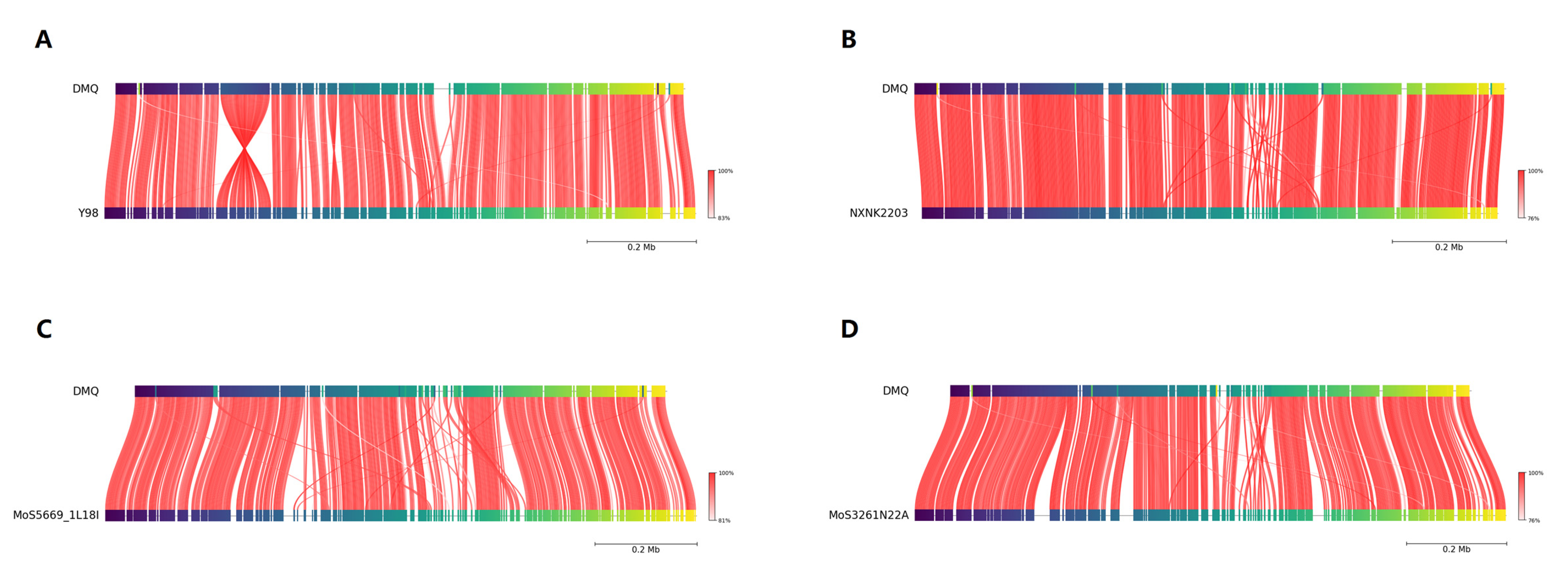

3.5. Phylogenomic and Structural Genomic Analysis

3.6. Microbial Community Analysis of the Ovine Lung Tissue Sample

4. Discussion

4.1. Potential Link Between M. ovipneumoniae Infection and Ovine Pulmonary Adenomatosis

4.2. Genomic Architecture and Functional Profile of IM-DMQ

4.3. Putative Virulence Determinants and Host–Pathogen Interplay

4.4. Genomic Comparison and Phylogenetic Context

4.5. Etiological Considerations from the Microbial Community Data

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dassanayake, R.P.; Shanthalingam, S.; Herndon, C.N.; Subramaniam, R.; Lawrence, P.K.; Bavananthasivam, J.; Cassirer, E.F.; Haldorson, G.J.; Foreyt, W.J.; Rurangirwa, F.R.; et al. Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae can predispose bighorn sheep to fatal Mannheimia haemolytica pneumonia. Vet. Microbiol. 2010, 145, 354–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rifatbegovic, M.; Maksimovic, Z.; Hulaj, B. Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae associated with severe respiratory disease in goats. Vet. Rec. 2011, 168, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lluch-Senar, M.; Delgado, J.; Chen, W.H.; Lloréns-Rico, V.; O’Reilly, F.J.; Wodke, J.A.; Unal, E.B.; Yus, E.; Martínez, S.; Nichols, R.J.; et al. Defining a minimal cell: Essentiality of small ORFs and ncRNAs in a genome-reduced bacterium. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2015, 11, 780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Citti, C.; Blanchard, A. Mycoplasmas and their host: Emerging and re-emerging minimal pathogens. Trends Microbiol. 2013, 21, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maksimović, Z.; Rifatbegović, M.; Loria, G.R.; Nicholas, R.A.J. Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae: A Most Variable Pathogen. Pathogens 2022, 11, 1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, D.; Ma, Y.; Li, M.; Li, Y.; Luo, H.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y. Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae induces inflammatory response in sheep airway epithelial cells via a MyD88-dependent TLR signaling pathway. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2015, 163, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tantengco, O.A.G.; Aquino, I.M.C.; de Castro Silva, M.; Rojo, R.D.; Abad, C.L.R. Association of mycoplasma with prostate cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol. 2021, 75, 102021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetti, F.; Silvestri, G.; Denaro, F.; Finesso, G.; Contreras-Galindo, R.; Munawwar, A.; Williams, S.; Davis, H.; Bryant, J.; Wang, Y.; et al. Mycoplasma DnaK expression increases cancer development in vivo upon DNA damage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2320859121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zella, D.; Curreli, S.; Benedetti, F.; Krishnan, S.; Cocchi, F.; Latinovic, O.S.; Denaro, F.; Romerio, F.; Djavani, M.; Charurat, M.E.; et al. Mycoplasma promotes malignant transformation in vivo, and its DnaK, a bacterial chaperone protein, has broad oncogenic properties. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E12005–E12014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logunov, D.Y.; Scheblyakov, D.V.; Zubkova, O.V.; Shmarov, M.M.; Rakovskaya, I.V.; Gurova, K.V.; Tararova, N.D.; Burdelya, L.G.; Naroditsky, B.S.; Ginzburg, A.L.; et al. Mycoplasma infection suppresses p53, activates NF-kappaB and cooperates with oncogenic Ras in rodent fibroblast transformation. Oncogene 2008, 27, 4521–4531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, S.; McPherson, J.D.; McCombie, W.R. Coming of age: Ten years of next-generation sequencing technologies. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2016, 17, 333–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Didelot, X.; Bowden, R.; Wilson, D.J.; Peto, T.E.A.; Crook, D.W. Transforming clinical microbiology with bacterial genome sequencing. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2012, 13, 601–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, K.R.; Besser, T.E.; Stalder, T.; Top, E.M.; Baker, K.N.; Fagnan, M.W.; New, D.D.; Schneider, G.M.; Gal, A.; Andrews-Dickert, R.; et al. Comparative genomic analysis identifies potential adaptive variation in Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae. Microb. Genom. 2024, 10, 001279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Einarsdottir, T.; Gunnarsson, E.; Hjartardottir, S. Icelandic ovine Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae are variable bacteria that induce limited immune responses in vitro and in vivo. J. Med. Microbiol. 2018, 67, 1480–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.Y.; Du, Y.Z.; Song, Y.P.; Zhou, P.; Chu, Y.F.; Wu, J.Y. Investigation of the Prevalence of Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae in Southern Xinjiang, China. J. Vet. Res. 2021, 65, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, G.; Zhao, J.M.; Hou, G.Y.; Zhou, H.L. Seroprevalence and molecular detection of Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae in goats in tropical China. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2014, 46, 1491–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besser, T.E.; Cassirer, E.F.; Potter, K.A.; VanderSchalie, J.; Fischer, A.; Knowles, D.P.; Herndon, D.R.; Rurangirwa, F.R.; Weiser, G.C.; Srikumaran, S. Association of Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae infection with population-limiting respiratory disease in free-ranging Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis canadensis). J. Clin. Microbiol. 2008, 46, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. fastp: An ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wick, R.R.; Judd, L.M.; Gorrie, C.L.; Holt, K.E. Unicycler: Resolving bacterial genome assemblies from short and long sequencing reads. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2017, 13, e1005595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parks, D.H.; Imelfort, M.; Skennerton, C.T.; Hugenholtz, P.; Tyson, G.W. CheckM: Assessing the quality of microbial genomes recovered from isolates, single cells, and metagenomes. Genome Res. 2015, 25, 1043–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seemann, T. Prokka: Rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2068–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syberg-Olsen, M.J.; Garber, A.I.; Keeling, P.J.; McCutcheon, J.P.; Husnik, F. Pseudofinder: Detection of Pseudogenes in Prokaryotic Genomes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2022, 39, msac153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finn, R.D.; Bateman, A.; Clements, J.; Coggill, P.; Eberhardt, R.Y.; Eddy, S.R.; Heger, A.; Hetherington, K.; Holm, L.; Mistry, J.; et al. Pfam: The protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, D222–D230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haft, D.H.; Selengut, J.D.; White, O. The TIGRFAMs database of protein families. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003, 31, 371–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finn, R.D.; Clements, J.; Eddy, S.R. HMMER web server: Interactive sequence similarity searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, W29–W37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M.; Goto, S.; Kawashima, S.; Okuno, Y.; Hattori, M. The KEGG resource for deciphering the genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, D277–D280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashburner, M.; Ball, C.A.; Blake, J.A.; Botstein, D.; Butler, H.; Cherry, J.M.; Davis, A.P.; Dolinski, K.; Dwight, S.S.; Eppig, J.T.; et al. Gene ontology: Tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat. Genet. 2000, 25, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apweiler, R.; Bairoch, A.; Wu, C.H.; Barker, W.C.; Boeckmann, B.; Ferro, S.; Gasteiger, E.; Huang, H.; Lopez, R.; Magrane, M.; et al. UniProt: The Universal Protein knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, D115–D119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatusov, R.L.; Galperin, M.Y.; Natale, D.A.; Koonin, E.V. The COG database: A tool for genome-scale analysis of protein functions and evolution. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Zeng, Z.; Xu, J.; Liu, Y.; Feng, J.; Chen, H.; He, Y.; et al. TBtools-II: A “one for all, all for one” bioinformatics platform for biological big-data mining. Mol. Plant 2023, 16, 1733–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolyen, E.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.R.; Bokulich, N.A.; Abnet, C.C.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Alexander, H.; Alm, E.J.; Arumugam, M.; Asnicar, F.; et al. Author Correction: Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baranowski, E.; Bergonier, D.; Sagné, E.; Hygonenq, M.C.; Ronsin, P.; Berthelot, X.; Citti, C. Experimental infections with Mycoplasma agalactiae identify key factors involved in host-colonization. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e93970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Tseng, C.W.; Kanci, A.; Citti, C.; Rosengarten, R.; Chiu, C.J.; Chen, Z.H.; Geary, S.J.; Browning, G.F.; Markham, P.F. MalF is essential for persistence of Mycoplasma gallisepticum in vivo. Microbiology 2013, 159, 1459–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdizadeh, S.; Masukagami, Y.; Tseng, C.W.; Markham, P.F.; De Souza, D.P.; Nijagal, B.; Tull, D.; Tatarczuch, L.; Browning, G.F.; Sansom, F.M. A Mycoplasma gallisepticum Glycerol ABC Transporter Involved in Pathogenicity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 87, e03112–e03120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, C.; Samwel, K.; Kahesa, C.; Mwaiselage, J.; West, J.T.; Wood, C.; Angeletti, P.C. Mycoplasma Co-Infection Is Associated with Cervical Cancer Risk. Cancers 2020, 12, 1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Li, J.Y.; Wu, J.; Meng, L.; Shou, C.C. Mycoplasma infections and different human carcinomas. World J. Gastroenterol. 2001, 7, 266–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yacoub, E.; Saed Abdul-Wahab, O.M.; Al-Shyarba, M.H.; Ben Abdelmoumen Mardassi, B. The Relationship between Mycoplasmas and Cancer: Is It Fact or Fiction ? Narrative Review and Update on the Situation. J. Oncol. 2021, 2021, 9986550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Luo, H.; Su, X.; Gan, T.; Wang, J.; Ye, Z.; Deng, Z.; He, J. Mycoplasma genitalium infection in the female reproductive system: Diseases and treatment. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1098276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetti, F.; Cocchi, F.; Latinovic, O.S.; Curreli, S.; Krishnan, S.; Munawwar, A.; Gallo, R.C.; Zella, D. Role of Mycoplasma Chaperone DnaK in Cellular Transformation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetti, F.; Silvestri, G.; Saadat, S.; Denaro, F.; Latinovic, O.S.; Davis, H.; Williams, S.; Bryant, J.; Ippodrino, R.; Rathinam, C.V.; et al. Mycoplasma DnaK increases DNA copy number variants in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2219897120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barykova, Y.A.; Logunov, D.Y.; Shmarov, M.M.; Vinarov, A.Z.; Fiev, D.N.; Vinarova, N.A.; Rakovskaya, I.V.; Baker, P.S.; Shyshynova, I.; Stephenson, A.J.; et al. Association of Mycoplasma hominis infection with prostate cancer. Oncotarget 2011, 2, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borchsenius, S.N.; Vishnyakov, I.E.; Chernova, O.A.; Chernov, V.M.; Barlev, N.A. Effects of Mycoplasmas on the Host Cell Signaling Pathways. Pathogens 2020, 9, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Tsai, S.; Lo, S.C. Alteration of gene expression profiles during mycoplasma-induced malignant cell transformation. BMC Cancer 2006, 6, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yus, E.; Maier, T.; Michalodimitrakis, K.; van Noort, V.; Yamada, T.; Chen, W.H.; Wodke, J.A.; Güell, M.; Martínez, S.; Bourgeois, R.; et al. Impact of genome reduction on bacterial metabolism and its regulation. Science 2009, 326, 1263–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juhas, M.; van der Meer, J.R.; Gaillard, M.; Harding, R.M.; Hood, D.W.; Crook, D.W. Genomic islands: Tools of bacterial horizontal gene transfer and evolution. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2009, 33, 376–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treangen, T.J.; Abraham, A.L.; Touchon, M.; Rocha, E.P. Genesis, effects and fates of repeats in prokaryotic genomes. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2009, 33, 539–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S.A.; McKenzie, R.E.; Fagerlund, R.D.; Kieper, S.N.; Fineran, P.C.; Brouns, S.J. CRISPR-Cas: Adapting to change. Science 2017, 356, eaal5056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbanus, M.L.; Quaile, A.T.; Stogios, P.J.; Morar, M.; Rao, C.; Di Leo, R.; Evdokimova, E.; Lam, M.; Oatway, C.; Cuff, M.E.; et al. Diverse mechanisms of metaeffector activity in an intracellular bacterial pathogen, Legionella pneumophila. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2016, 12, 893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Wang, J.; Han, R.; Wang, L.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, A.Y.; Xin, J.; Li, S.; Zeng, Y.; Shao, G.; et al. Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae evades complement activation by binding to factor H via elongation factor thermo unstable (EF-Tu). Virulence 2020, 11, 1059–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegde, S.; Rosengarten, R.; Chopra-Dewasthaly, R. Disruption of the pdhB pyruvate dehydrogenase [corrected] gene affects colony morphology, in vitro growth and cell invasiveness of Mycoplasma agalactiae. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0119706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutscher, A.T.; Jenkins, C.; Minion, F.C.; Seymour, L.M.; Padula, M.P.; Dixon, N.E.; Walker, M.J.; Djordjevic, S.P. Repeat regions R1 and R2 in the P97 paralogue Mhp271 of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae bind heparin, fibronectin and porcine cilia. Mol. Microbiol. 2010, 78, 444–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, T.; Artiushin, S.; Minion, F.C. Cloning and functional analysis of the P97 swine cilium adhesin gene of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae. J. Bacteriol. 1997, 179, 1317–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, C.; Pitzer, J.; Minion, F.C. In vivo expression analysis of the P97 and P102 paralog families of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae. Infect. Immun. 2005, 73, 7784–7787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talenton, V.; Baby, V.; Gourgues, G.; Mouden, C.; Claverol, S.; Vashee, S.; Blanchard, A.; Labroussaa, F.; Jores, J.; Arfi, Y.; et al. Genome Engineering of the Fast-Growing Mycoplasma feriruminatoris toward a Live Vaccine Chassis. ACS Synth. Biol. 2022, 11, 1919–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evsyutina, D.V.; Fisunov, G.Y.; Pobeguts, O.V.; Kovalchuk, S.I.; Govorun, V.M. Gene Silencing through CRISPR Interference in Mycoplasmas. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trueeb, B.S.; Gerber, S.; Maes, D.; Gharib, W.H.; Kuhnert, P. Tn-sequencing of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae and Mycoplasma hyorhinis mutant libraries reveals non-essential genes of porcine mycoplasmas differing in pathogenicity. Vet. Res. 2019, 50, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, H.; Raheem, A.; Ma, Q.; Liang, X.; Guo, Y.; Lu, D. Exploring Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae NXNK2203 infection in sheep: Insights from histopathology and whole genome sequencing. BMC Vet. Res. 2024, 20, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamath, P.L.; Manlove, K.; Cassirer, E.F.; Cross, P.C.; Besser, T.E. Genetic structure of Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae informs pathogen spillover dynamics between domestic and wild Caprinae in the western United States. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 15318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Ptacek, T.; Osborne, J.D.; Crabb, D.M.; Simmons, W.L.; Lefkowitz, E.J.; Waites, K.B.; Atkinson, T.P.; Dybvig, K. Comparative genome analysis of Mycoplasma pneumoniae. BMC Genom. 2015, 16, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besser, T.E.; Highland, M.A.; Baker, K.; Cassirer, E.F.; Anderson, N.J.; Ramsey, J.M.; Mansfield, K.; Bruning, D.L.; Wolff, P.; Smith, J.B.; et al. Causes of pneumonia epizootics among bighorn sheep, Western United States, 2008–2010. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2012, 18, 406–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, J.B. Survey of Mycoplasma (Mesomycoplasma) ovipneumoniae, Mannheimia haemolytica, and Pasteurella multocida in pneumonic lungs from sheep slaughtered at 3 abattoirs in New South Wales, Australia. Can. J. Vet. Res. 2025, 89, 83–87. [Google Scholar]

- Cid, D.; Pinto, C.; Domínguez, L.; Vela, A.I.; Fernández-Garayzábal, J.F. Strength of association between isolation of Pasteurella multocida and consolidation lesions in ovine pneumonic pasteurellosis. Vet. Microbiol. 2020, 248, 108823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type | Number | Total_len | Average_len | Percentage of Genome (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | 1529 | 682,833 | 447 | 65.58 |

| CDS | 1493 | 675,450 | 452 | 64.87 |

| tRNA | 30 | 2367 | 79 | 0.23 |

| 23S rRNA | 1 | 2882 | 2882 | 0.28 |

| 16S rRNA | 1 | 1527 | 1527 | 0.15 |

| 5S rRNA | 1 | 69 | 69 | 0.01 |

| tmRNA | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 |

| misc_RNA | 3 | 538 | 179 | 0.05 |

| Strain | Accession Number | Years of Isolation | Location of Isolation | Size (bp) | G + C % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y98 | CP118522.1 | 1971 | Australia | 1,081,520 | 29 |

| MoS5669_1L18I | CP134945.1 | 2018 | Iceland | 1,158,390 | 29 |

| IM-DMQ | Not yet uploaded | 2019 | Inner Mongolia of China | 1,039,804 | 29.15 |

| NXNK2203 | CP124621.1 | 2022 | NingXia of China | 1,014,835 | 29 |

| MoS3261N22A | CP134944.1 | 2022 | Austria | 1,182,340 | 29 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Dai, L.; Wang, N.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, Y.; Song, Y.; Liu, W.; Cao, X.; Shi, J.; Zhao, S.; Bai, F. Genomic Characterization of a Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae Strain from Hu Sheep in Inner Mongolia, China. Vet. Sci. 2026, 13, 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci13010079

Dai L, Wang N, Zhang F, Zhang Y, Song Y, Liu W, Cao X, Shi J, Zhao S, Bai F. Genomic Characterization of a Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae Strain from Hu Sheep in Inner Mongolia, China. Veterinary Sciences. 2026; 13(1):79. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci13010079

Chicago/Turabian StyleDai, Lingli, Na Wang, Fan Zhang, Yuemei Zhang, Yue Song, Wei Liu, Xiaodong Cao, Jingyu Shi, Shihua Zhao, and Fan Bai. 2026. "Genomic Characterization of a Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae Strain from Hu Sheep in Inner Mongolia, China" Veterinary Sciences 13, no. 1: 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci13010079

APA StyleDai, L., Wang, N., Zhang, F., Zhang, Y., Song, Y., Liu, W., Cao, X., Shi, J., Zhao, S., & Bai, F. (2026). Genomic Characterization of a Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae Strain from Hu Sheep in Inner Mongolia, China. Veterinary Sciences, 13(1), 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci13010079