Agreeing Language in Veterinary Endocrinology (ALIVE): Hypothyroidism, Hyperthyroidism, (Euglycaemic) Diabetic Ketosis/Ketoacidosis, and Diabetic Remission—A Modified Delphi-Method-Based System to Create Consensus Definitions

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Panel Recruitment

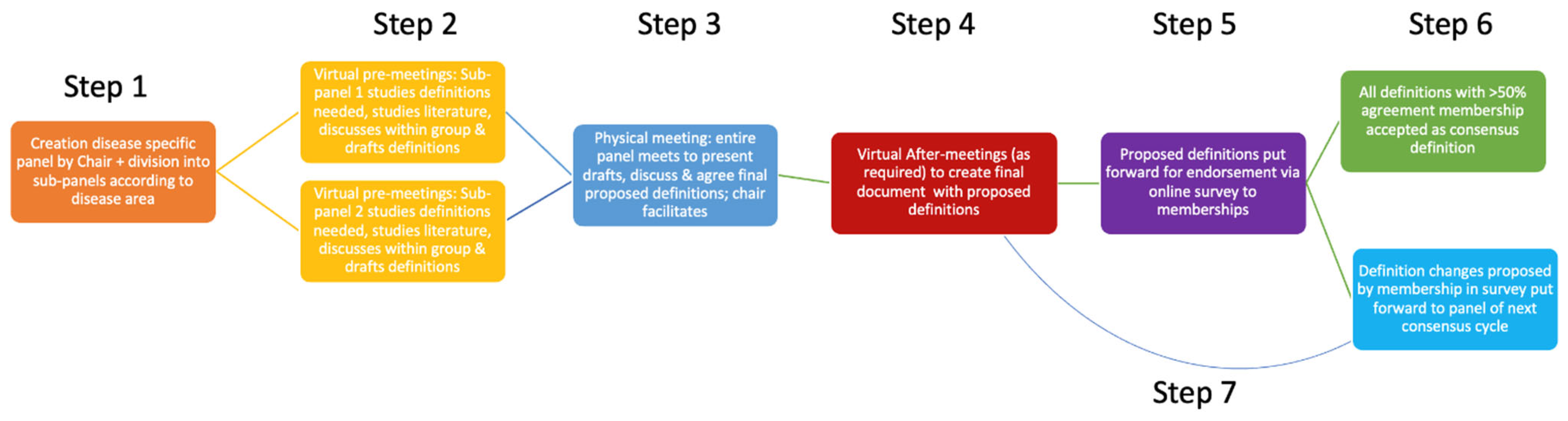

2.2. Delphi Process

2.3. Subdivision and Pre-Meetings

2.4. In-Person Consensus Meeting

2.5. Panel Consensus Criteria

2.6. Membership Endorsement

2.7. Funding and Independence

3. Results

3.1. Hyperthyroidism

3.1.1. Euthyroidism (Endorsement 101/105)

3.1.2. Hyperthyroidism (Endorsement 100/105)

3.1.3. Overt Hyperthyroidism (Endorsement 97/105)

3.1.4. Thyrotoxicosis (Endorsement 105/105)

3.1.5. Thyroid Storm (Endorsement 99/105)

3.1.6. Subclinical Hyperthyroidism (Endorsement 97/105)

3.1.7. Primary Hyperthyroidism (Endorsement 103/105)

3.1.8. Central Hyperthyroidism (Endorsement 104/105)

3.1.9. Secondary and Tertiary Hyperthyroidism (Endorsement 104/105)

3.1.10. Iatrogenic Hypothyroidism (Endorsement 104/105)

3.1.11. Exogenous Causes of Thyrotoxicosis (Endorsement 103/105)

3.1.12. Iatrogenic Thyrotoxicosis (Endorsement 99/105)

3.1.13. Dietary Thyrotoxicosis (Endorsement 105/105)

3.1.14. Goitre (Endorsement 97/105)

3.1.15. Thyroid Palpation Technique (Endorsement 96/105)

3.1.16. Ectopic Overactive Thyroid Disease (Endorsement 103/105)

3.1.17. Follicular Nodular Goitre (Endorsement 101/105)

3.1.18. Graves’ Disease (Endorsement 102/105)

3.1.19. Adenomatous Hyperplasia or Adenoma of the Thyroid Gland (Endorsement 101/105)

3.1.20. Thyroid Carcinoma (Endorsement 100/105)

- -

- Specific criteria for histopathological characterisation of thyroid carcinoma have been described [23].

3.1.21. SHIM-RAD (Endorsement 103/105)

3.1.22. Risk Factors for Development of Hyperthyroidism (Endorsement 103/105)

3.1.23. Intrinsic and Extrinsic Risk Factors for Development of Hyperthyroidism (Endorsement 103/105)

3.1.24. Thyroid Scintigraphy (Endorsement 105/105)

- -

- Other imaging modalities, such as ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), do not provide any functional information but can depict the size and internal structure (gross pathology) of the thyroid gland.

3.1.25. ALIVE Criteria for Diagnosis of Hyperthyroidism—Primary Disease (Endorsement 97/105)

- If total T4 is increased in the absence of supportive signalment and clinical signs, reassessment of clinical status (especially if total T4 is clearly increased) or repeat T4 measurement (if total T4 is marginally increased) is recommended.

- If there are supportive clinical signs, but total T4 is not increased and is in the upper end of the reference interval, hyperthyroidism is possible. In these cases, concurrent non-thyroidal disease can be associated with suppression of total T4 to within reference interval. Subclinical hyperthyroidism is associated with within the reference interval total T4 concentrations. Further diagnostic tests for hyperthyroidism could be considered (demonstration of concurrent suppression of TSH, concurrent increased free T4, increased technetium uptake on thyroid scintigraphy or increased total T4 on repeated testing).

- Initial measurement of concurrent total T4 and TSH concentrations may provide more information than total T4 alone.

- Lack of suppression of TSH makes hyperthyroidism unlikely.

3.1.26. ALIVE Criteria for Diagnosis Hyperthyroidism—Central Disease (Endorsement 102/105)

- -

- There are currently no reports of central hyperthyroidism in cats or dogs.

3.1.27. ALIVE Criteria for Diagnosis Hyperthyroidism—Exogenous Disease (Endorsement 102/105)

3.1.28. ALIVE Criteria for Diagnosis of Iatrogenic Hypothyroidism (Endorsement 102/105)

- Currently, it is challenging to predict whether a cat will be permanently or transiently affected by iatrogenic hypothyroidism after thyroidectomy or radioactive iodine therapy. Nevertheless, a return to euthyroidism is thought likely in most cats and is often seen within one to two years of documenting iatrogenic hypothyroidism. However, a return to euthyroidism has taken more than seven years in some cats.

- Cats with overt hypothyroidism are more likely to have more prolonged or permanent hypothyroidism than cats with subclinical disease. For this reason, clinicians should consider monitoring circulating total T4, TSH, and creatinine concentrations at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months after surgical thyroidectomy or radioactive iodine therapy and then every 6–12 months thereafter. Even if most cats return to euthyroidism in the long-term, thyroid hormone supplementation might help prevent adverse effects of insufficient thyroid hormone concentrations (e.g., worsening azotaemia).

- Specifically, thyroid hormone supplementation should be considered in cats with persistent overt biochemical hypothyroidism (verified by demonstrating low circulating T4 and increased TSH concentrations) on at least two occasions 1–3 months apart, especially with worsening azotaemia (which will develop in over half of cats with overt biochemical hypothyroidism) or in the presence of any supportive clinical signs of hypothyroidism.

- In addition, thyroid hormone supplementation should be considered in cats with persistent subclinical hypothyroidism (verified by demonstrating low reference interval circulating T4 and increased TSH concentrations) on at least two occasions 3–6 months apart. Given the lack of clinical signs in these cats, the decision to start supplementation is primarily based on the development of progressive azotaemia (which can develop in up to a third of these cats).

3.1.29. Iatrogenic Hypoparathyroidism (Endorsement 99/105)

- A history of potential for iatrogenic damage to the parathyroid glands;

- An ionised blood calcium below the reference interval of the methodology used;

- A documented inappropriately low blood PTH.

- Comments:

- The lack of elevation of PTH above the reference interval, despite a below reference interval blood calcium, is considered inappropriate and thus consistent with hypoparathyroidism.

- Given the labile nature of PTH, ALIVE recommends the use of an appropriately validated assay to measure PTH, using recommended sampling, storage, and transportation methods; a laboratory participating in an external quality assurance programme is also recommended.

- A diagnosis of “suspected” iatrogenic hypoparathyroidism could be made without measurement of PTH.

- A diagnosis of “suspected” iatrogenic hypoparathyroidism could be made with documentation of a low total calcium when ionised calcium is not available.

3.1.30. TSH Stimulation Test (Cats) (Endorsement 105/105)

3.1.31. TRH Stimulation Test (Cats) (Endorsement 99/105)

- The panel does not use this test but recognises that it can be used in certain situations.

- Administration of TRH often causes severe cholinergic and central nervous system-mediated reactions. Within seconds of being given TRH, cats often exhibit transient but severe salivation, tachypnoea, micturition, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhoea.

- The TRH stimulation test would likely be a good diagnostic test if TSH secretion is evaluated directly. One study shows that TRH will stimulate feline secretion using low doses of TRH in healthy cats [24]. By using these low doses, less side effects are being observed.

- The TRH stimulation as a diagnostic test, giving lower doses and measuring TSH directly should be investigated in hyperthyroid cats, cats with nonthyroidal illness, and clinically normal cats to establish testing protocols and diagnostic guidelines for interpretation.

3.1.32. Triiodothyronine (T3) Suppression Test (Endorsement 103/105)

3.1.33. TSH Suppression (Endorsement 102/105)

3.1.34. Unmasking CKD (Endorsement 102/105)

3.1.35. Treatment Success in Hyperthyroidism (Endorsement 95/105)

3.1.36. Medical Treatment Hyperthyroidism (Palliative) (Endorsement 104/105)

3.1.37. Surgical Treatment Hyperthyroidism (Curative) (Endorsement 99/105)

3.1.38. Radioactive Treatment Hyperthyroidism (Curative) (Endorsement 105/105)

3.1.39. Diet Management Hyperthyroidism (Palliative) (Endorsement 103/105)

3.1.40. Heat Ablation, Ethanol Injection Treatment Hyperthyroidism (Endorsement 102/105)

3.1.41. Chemotherapy and External Beam Radiation Treatment for Hyperthyroidism (Endorsement 105/105)

3.1.42. TSH Suppression After Removal of Thyroid Carcinoma (Endorsement 100/105)

3.2. Hypothyroidism

3.2.1. Hypothyroidism (Endorsement 105/105)

3.2.2. Primary Hypothyroidism (Endorsement 105/105)

- Primary hypothyroidism can be due to several processes including immune-mediated destruction, thyroid atrophy, neoplasia, congenital disease, or iatrogenic causes including surgery, drugs, and radiation.

3.2.3. Secondary Hypothyroidism (Endorsement 105/105)

- This can be due to several processes including neoplasia, hypophysitis, or congenital diseases, as well as iatrogenic causes including surgery or radiation.

3.2.4. Tertiary Hypothyroidism (Endorsement 105/105)

- This is poorly described in dogs and not yet reported in cats.

3.2.5. Central Hypothyroidism (Endorsement 104/105)

3.2.6. Congenital Hypothyroidism (Endorsement 105/105)

3.2.7. Genetic Hypothyroidism (Endorsement 102/105)

3.2.8. Thyroid Dysgenesis (Endorsement 105/105)

3.2.9. Thyroid Dyshormonogenesis (Endorsement 104/105)

3.2.10. Thyroid Atrophy (Endorsement 102/105)

3.2.11. Lymphocytic Thyroiditis (Endorsement 103/105)

3.2.12. Neoplasia-Induced Primary Hypothyroidism (Endorsement 105/105)

3.2.13. Trauma-Induced Hypothyroidism (Endorsement 104/105)

3.2.14. Silent/Subclinical Thyroiditis (Endorsement 102/105)

3.2.15. Subclinical Hypothyroidism (Endorsement 102/105)

- Increased TSH concentration with reference interval total T4 concentration can also be seen during recovery from illness, following removal of thyroid suppressive medications and in certain illnesses such as primary hypoadrenocorticism.

- T4 autoantibodies may also result in an artefactual increase in T4 concentration to within reference interval (or above).

3.2.16. Myxoedema (Endorsement 105/105)

3.2.17. Hypothyroid Crisis (Formerly Known as Myxoedema Coma) (Endorsement 105/105)

- In human medicine, myxoedema is frequently but not consistently observed. Coma is also uncommon. The underlying pathogenesis is related to decompensated hypothyroidism not myxoedema. As a result, the term hypothyroid crisis is preferred.

- The condition is rare, not well characterised in dogs, and has not been reported in cats.

3.2.18. ALIVE Criteria for Diagnosis of Canine Primary Hypothyroidism (Endorsement 102/105)

- Decreased total T4 with increased cTSH concentrations are consistent with a diagnosis of primary hypothyroidism (observed in approximately 70% of cases).

- Decreased total T4 with reference interval cTSH concentrations are observed in approximately 30% of dogs with primary hypothyroidism. However, this combination of results can also be observed with non-thyroidal illness, in dogs receiving thyroid suppressive medications, and in some healthy dogs, particularly within certain breeds.

- The most definitive methods for diagnosis of primary hypothyroidism are the rhTSH stimulation test and thyroid scintigraphy.

- Free T4 (by equilibrium dialysis) is less affected by nonthyroidal illness.

- Thyroglobulin or thyroid hormone autoantibody positivity provides evidence of lymphocytic thyroiditis but not thyroid hypofunction.

- Treatment trials with levothyroxine are not recommended unless clinical suspicion is high despite a lack of supportive diagnostic testing.

- Reference interval or increased total T4 concentrations are seen in a small proportion of dogs with primary hypothyroidism. This is most commonly due to assay interference by T4 autoantibodies. Free T4 measurement by equilibrium dialysis is less affected by these antibodies and may be used to support a diagnosis.

- When possible, thyroid function testing is not recommended in animals with severe non-thyroidal illness or while receiving thyroid suppressive medications. If testing is necessary in such cases, results should be interpreted with extreme caution.

3.2.19. ALIVE Criteria for Diagnosis of Central Hypothyroidism (Endorsement 101/105)

3.2.20. ALIVE Criteria for the Diagnosis of Subclinical Hypothyroidism (Endorsement 104/105)

3.2.21. Non-Thyroidal Illness Syndrome (NTIS) (Endorsement 103/105)

- Use of the term euthyroid sick syndrome is discouraged because thyroid function may be suppressed.

- The syndrome is typically characterised by decreased circulating total T4 concentrations. Total T3 concentrations are also commonly decreased. Free T4 concentrations (by equilibrium dialysis) are typically less affected than total T4 but can be decreased in severe disease or, rarely, increased. TSH concentrations may decrease below the lower limit of quantification of the current assay.

- This is a transient state, provided the underlying cause is removed. The degree of thyroid hormone suppression is proportional to the severity of non-thyroidal illness and may have prognostic significance.

- There is no evidence that thyroid hormone supplementation is beneficial in dogs or cats.

- During recovery from non-thyroidal illness, TSH concentrations may be transiently increased as thyroid hormone concentrations normalise.

- In animals with NTIS, thyroid hormone concentrations are inversely correlated with illness severity. In other words, the lower the TT4, fT4, and T3 concentrations, the more severe the animal’s disease and the higher the risk of death. NTIS is associated with high cytokine and serum cortisol concentrations, both of which have a suppressive effect at various levels within the hypothalamic–pituitary–thyroid (HPT) axis depending on the nature of the illness, acuteness of onset, and the severity of inflammation.

3.2.22. Thyroid Hormone Altering Medication (Endorsement 103/105)

- Most of these medications have a suppressive effect on total T4 concentration.

- These drugs include glucocorticoids, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, barbiturates, and clomipramine.

- Measurement of free T4 concentration often has limited benefit due to variable effects on T4 binding.

3.2.23. Hypothyroidism-Inducing Medication (Endorsement 105/105)

3.2.24. Threshold for Waiting After Illness, After Stopping Thyroid-Suppressive Medications Before Testing Thyroid Function (Endorsement 103/105)

- It is generally recommended to wait at least four to six weeks following discontinuation of suppressive drug therapy before performing thyroid function testing. However, this recommendation has limited supporting evidence and likely varies depending on the drug, dose, and duration of therapy.

3.2.25. Successful Treatment of Canine Hypothyroidism (Endorsement 101/105)

3.2.26. Transient Hypothyroidism (Endorsement 103/105)

3.3. Definitions for Thyroid Assessment Tests

3.3.1. Total Thyroxine (Total T4 or TT4) (Endorsement 103/105)

3.3.2. Free Thyroxine (Free T4 or fT4) (Endorsement 105/105)

- -

- Immunoassays for free T4 do not include 8-anilino-1-naphthalene-sulphonic acid (ANS), and theoretically only unbound T4 is able to interact with detection antibodies.There are two distinct methods commonly used for free T4 measurement.One method involves equilibrium dialysis to separate the protein-bound from the free T4, followed by an ultrasensitive radioimmunoassay for measurement of T4 in the dialysate. This method is not widely available, subject to stringent sample handling requirements, and is more difficult for routine quality control. Nevertheless, it is the only method currently commercially available that measures true free T4 concentrations capable of providing more diagnostic information than total T4 alone.The second method does not include a separation step and is made possible through the use of a labelled T4 analogue that theoretically does not react with thyroid hormone binding proteins and is thus available to compete with free T4 for antibody binding sites.Because the protein binding kinetic assumptions underlying analogue assays can be violated in certain physiological and pathological states, analogue free T4 methods may be subject to interference that generates results that do not provide more information than obtained by total T4 measurement. Circumstances that promote the release of T4 from binding proteins such as increased free fatty acid concentrations and furosemide therapy will cause increases in the measured free T4.In dogs, subsets of thyroid hormone antibodies (T3AA and T4AA) or anti-thyroid antibodies can interfere with the immunoassay measurement of their respective hormones. Interference is more likely with analogue methods compared with those that utilise equilibrium dialysis for separation of free from bound thyroid hormones. For the analogue methodologies commonly used for free T4 measurement, T4 AAs can cause falsely higher (results that can potentially increase into or above the reference interval) free T4 results. Free T4 results may be affected, with or without a similar effect on total T4 results.

3.3.3. Thyrotropin (TSH) (Endorsement 96/105)

3.3.4. Minimum Canine Hypothyroidism Panel (Endorsement 105/105)

- -

- The additional inclusion of TgAA or T4AA in a profile, if negative, reassures that there is no potential antibody interference in thyroid hormone results.The inclusion of free T4 by equilibrium dialysis may assist in correctly identifying the effects of non-thyroidal illness or medications.

3.3.5. Minimum Feline Hyperthyroidism Panel (Endorsement 102/105)

- -

- Emerging, more sensitive TSH tests might help in the future. A low TSH concentration (<0.01 ng/mL) detected by such sensitive tests supports the diagnosis of hyperthyroidism (example test: pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38382201 [accessed on 4 April 2024]).

3.3.6. T3 and T4 Autoantibodies (T3AA and T4AA) (Endorsement 104/105)

3.3.7. Thyroglobulin Autoantibodies (TgAA) (Endorsement 104/105)

- -

- In human thyroiditis, the more commonly detected antibodies are anti-thyroperoxidase, but these are inconsistently found in the canine disease.A commercial canine TgAA ELISA is available and widely used.In-house-derived methods are also in use.Whichever method is used, it is important that steps are taken in the method to mitigate the possibility of misleading results from non-specific binding of non-TgAA antibodies.Autoantibodies do not provide an indication of thyroid function, and their sole presence do not provide an indication for treatment.

3.3.8. Total Triiodothyronine (Total T3 or TT3) (Endorsement 103/105)

3.3.9. Free Triiodothyronine (Free T3 or fT3) (Endorsement 105/105)

3.4. Updates Definitions Previous ALIVE Cycles

3.4.1. Diabetic Remission (Endorsement 105/105)

- -

- The patient would still be considered to be in a state of diabetic remission if the patient continues to receive a specific dietary treatment.

3.4.2. Diabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA) (Endorsement 104/105)

- Diagnosis of DM according to ALIVE criteria;

- Demonstration of ketonaemia defined as increased beta-hydroxybutyrate concentration, AND/OR ketonuria or ketonaemia, defined as detectable ketones using nitroprusside test strips for ketonuria or ketonaemia;

- Demonstration of metabolic acidosis defined as a venous/arterial blood pH < 7.35 and decreased bicarbonate.

- -

- When blood gas analysis is unavailable, a patient that is unwell and meeting the above remaining criteria should be suspected of suffering from DKA.Demonstration of ketonuria or elevated blood ketones in an animal that is clinically well means the animal will not be suffering from DKA. Instead, this constitutes “Diabetic Ketosis”.

3.4.3. Diabetic Ketosis (DK) (Endorsement 102/105)

- Diagnosis of DM according to ALIVE criteria

- Demonstration of ketonaemia defined as increased beta-hydroxybutyrate concentration, AND/OR ketonuria or ketonaemia, defined as detectable ketones using nitroprusside test strips for ketonuria or ketonaemia;

- Demonstration of absence of metabolic acidosis.

- -

- When blood gas analysis is unavailable, a patient which is well and meets the above remaining criteria should be suspected of DK.Demonstration of ketonuria or elevated blood ketones in an animal that is clinically well means the animal will not be suffering from DKA.There is currently no evidence that diabetic ketosis constitutes a greater risk of future DKA.

3.4.4. Euglycaemic Diabetic Ketoacidosis (eDKA) (Endorsement 103/105)

- -

- This condition can be encountered when patients have been receiving sodium glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitor and/or insulin treatment.When blood gas analysis is unavailable, a patient which is unwell and meets the eDKA remaining criteria should be suspected of suffering from eDKA.Demonstration of ketonuria or elevated blood ketones in an animal that is clinically well means the animal will not be suffering from eDKA. Instead, this constitutes “Euglycaemic Diabetic Ketosis” (eDK).

3.4.5. Euglycaemic Diabetic Ketosis (eDK) (Endorsement 101/105)

- -

- Demonstration of ketonuria or elevated blood ketones in an animal that is clinically well means the animal will not be suffering from eDKA.There is currently no evidence that eDK constitutes a greater risk of future (e)DKA.

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ALIVE | Agreeing Language in Veterinary Endocrinology |

| ESVE | European Society of Veterinary Endocrinology |

| SCE | Society of Comparative Endocrinology |

References

- Niessen, S.J.; Bjornvad, C.; Church, D.B.; Davison, L.; Esteban-Saltiveri, D.; Fleeman, L.M.; Forcada, Y.; Fracassi, F.; Gilor, C.; Hanson, J.; et al. Agreeing Language in Veterinary Endocrinology (ALIVE): Diabetes mellitus-a modified Delphi-method-based system to create consensus disease definitions. Vet. J. 2022, 289, 105910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niessen, S.J.; Behrend, E.N.; Fracassi, F.; Church, D.B.; Foster, S.F.; Galac, S.; Melian, C.; Pöppl, Á.G.; Ramsey, I.K.; Sieber-Ruckstuhl, N.S.; et al. Agreeing Language in Veterinary Endocrinology (ALIVE): Cushing’s Syndrome and Hypoadrenocorticism-A Modified Delphi-Method-Based System to Create Consensus Definitions. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hsu, C.C.; Sandford, B.A. The Delphi technique: Making sense of consensus. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 2007, 12, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Boulkedid, R.; Abdoul, H.; Loustau, M.; Sibony, O.; Alberti, C. Using and reporting the Delphi method for selecting healthcare quality indicators: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e20476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darling, G.; Malthaner, R.; Dickie, J.; McKnight, L.; Nhan, C.; Hunter, A.; McLeod, R.S.; Lung Cancer Surgery Expert Panel. Quality indicators for non-small cell lung cancer operations with use of a modified Delphi consensus process. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2014, 98, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bleijlevens, M.H.; Wagner, L.M.; Capezuti, E.; Hamers, J.P.; International Physical Restraint Workgroup. International Physical Restraint Workgroup. Physical restraints: Consensus of a research definition using a modified Delphi technique. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2016, 64, 2307–2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rioja-Lang, F.; Bacon, H.; Connor, M.; Dwyer, C.M. Rabbit welfare: Determining priority welfare issues for pet rabbits using a modified Delphi method. Vet. Rec. Open 2019, 6, e000363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rioja-Lang, F.C.; Connor, M.; Bacon, H.; Dwyer, C.M. Determining a welfare prioritization for horses using a delphi method. Animals 2020, 10, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, D.; Heale, R. What are Delphi studies? Evid. Based Nurs. 2020, 23, 68–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Kell, A.L.; Davison, L.J. Etiology and Pathophysiology of Diabetes Mellitus in Dogs. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Small Anim. Pract. 2023, 53, 493–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nivy, R.; Bar-Am, Y.; Retzkin, H.; Bruchim, Y.; Mazaki-Tovi, M. Preliminary evaluation of the impact of periodontal treatment on markers of glycaemic control in dogs with diabetes mellitus: A prospective, clinical case series. Vet. Rec. 2024, 194, e3310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothlin-Zachrisson, N.; Öhlund, M.; Röcklinsberg, H.; Holst, B.S. Survival, remission, and quality of life in diabetic cats. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2023, 37, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kwon, S.-C.; An, J.-H.; Kim, D.-H.; Youn, H.-Y. Glycated Albumin and Continuous Glucose Monitoring Metrics in Dogs with Diabetes Mellitus: A Pilot Study. Animals 2025, 15, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Paulin, M.V.; Snead, E.C.R. Serum cholesterol disturbances in dogs with common endocrinopathies at the time of diagnosis: A retrospective study. BMC Vet. Res. 2025, 21, 138. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, A.K.; Behrend, E.B. SGLT2 inhibitor use in the management of feline diabetes mellitus. J. Vet. Pharmacol. Ther. 2025, 48, 19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Patra, S.; McMillan, C.J.; Snead, E.R.; Warren, A.L.; Cosford, K.; Chelikani, P.K. Feline Diabetes Is Associated with Deficits in Markers of Insulin Signaling in Peripheral Tissues. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, S.; Neumann, U.H.; McMillan, C.J.; Snead, E.R.; Shannon, C.P.; Lam, K.K.; Chelikani, P.K. Diabetic and Overweight Cats Have Altered Gut Microbial Diversity and Composition. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5069681 (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Gilor, C.; Fleeman, L. Chapter 292: Diabetes Mellitus in cats. In Ettinger’s Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 9th ed.; Côté, E., Ettinger, S., Eds.; Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2024; Volume 2, pp. 1990–2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ruijter, B.E.W.; Bik, C.A.; Schofield, I.; Niessen, S.J.M. External validation of a United Kingdom primary-care Cushing’s prediction tool in a population of referred Dutch dogs. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2023, 37, 2052–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celliers, A.; Pazzi, P.; Mitchell, E.; Lensink, A.; Raseasala, N. Subdiagnostic Cushing’s syndrome in a Labrador retriever diagnosed with progesterone-secreting adrenocortical neoplasia and late liver metastasis. Vet. Rec. Case Rep. 2024, 12, e976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleeman, L.; Barrett, R. Cushing’s Syndrome and Other Causes of Insulin Resistance in Dogs, Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice; Elsevier: Amsterdam, the Netherlands, 2023; Volume 53, pp. 711–730. ISSN 0195-5616. ISBN 9780323940238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.; Cannon, M.; Church, D.; Fleeman, L.; Fracassi, F.; Gilor, C.; Mott, J.; Niessen, S. iCatCare 2025 consensus guidelines on the diagnosis and management of diabetes mellitus in cats. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2025, 27, 1098612X251399103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kiupel, M.; Capen, C.; Miller, M.; Smedley, R. Histological classification of tumours of the endocrine system of domestic animals. In WHO International Histological Classification of Tumours of Domestic Animals; Schulman, F.Y., Ed.; Armed Forces Institute of Pathology: Washington, DC, USA, 2008; pp. 25–39. [Google Scholar]

- Černá, P.; Antonakakis, M.; Peralta, J.; Kofron, K.; Hawley, J.; Morris, A.; Lappin, M.R. Total thyroxine and thyroid-stimulating hormone responses of healthy cats to different doses of thyrotropin-releasing hormone. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 2024, 36, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, M.E.; Dougherty, E.; Rishniw, M. Evaluation of a novel, sensitive thyroid-stimulating hormone assay as a diagnostic test for thyroid disease in cats. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2024, 85, ajvr.23.12.0278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Niessen, S.J.M.; Shiel, R.; Wehner, A.; Campos, M.; Daminet, S.; Fracassi, F.; Graham, P.; Korchia, J.; Lathan, P.; Leal, R.; et al. Agreeing Language in Veterinary Endocrinology (ALIVE): Hypothyroidism, Hyperthyroidism, (Euglycaemic) Diabetic Ketosis/Ketoacidosis, and Diabetic Remission—A Modified Delphi-Method-Based System to Create Consensus Definitions. Vet. Sci. 2026, 13, 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci13010035

Niessen SJM, Shiel R, Wehner A, Campos M, Daminet S, Fracassi F, Graham P, Korchia J, Lathan P, Leal R, et al. Agreeing Language in Veterinary Endocrinology (ALIVE): Hypothyroidism, Hyperthyroidism, (Euglycaemic) Diabetic Ketosis/Ketoacidosis, and Diabetic Remission—A Modified Delphi-Method-Based System to Create Consensus Definitions. Veterinary Sciences. 2026; 13(1):35. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci13010035

Chicago/Turabian StyleNiessen, Stijn J. M., Robert Shiel, Astrid Wehner, Miguel Campos, Sylvie Daminet, Federico Fracassi, Peter Graham, Jérémie Korchia, Patty Lathan, Rodolfo Leal, and et al. 2026. "Agreeing Language in Veterinary Endocrinology (ALIVE): Hypothyroidism, Hyperthyroidism, (Euglycaemic) Diabetic Ketosis/Ketoacidosis, and Diabetic Remission—A Modified Delphi-Method-Based System to Create Consensus Definitions" Veterinary Sciences 13, no. 1: 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci13010035

APA StyleNiessen, S. J. M., Shiel, R., Wehner, A., Campos, M., Daminet, S., Fracassi, F., Graham, P., Korchia, J., Lathan, P., Leal, R., Miceli, D. D., Mooney, C. T., Perez Alenza, M. d. l. D., Peterson, M. E., Schoeman, J. P., & on behalf of the ESVE/SCE membership. (2026). Agreeing Language in Veterinary Endocrinology (ALIVE): Hypothyroidism, Hyperthyroidism, (Euglycaemic) Diabetic Ketosis/Ketoacidosis, and Diabetic Remission—A Modified Delphi-Method-Based System to Create Consensus Definitions. Veterinary Sciences, 13(1), 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci13010035