Molecular Characterization of an H3N2 Canine Influenza Virus Isolated from a Dog in Jiangsu, China, in 2025

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

2.2. Virus Isolation, Identification, and Genomic Sequences

2.3. Phylogenetic Analysis

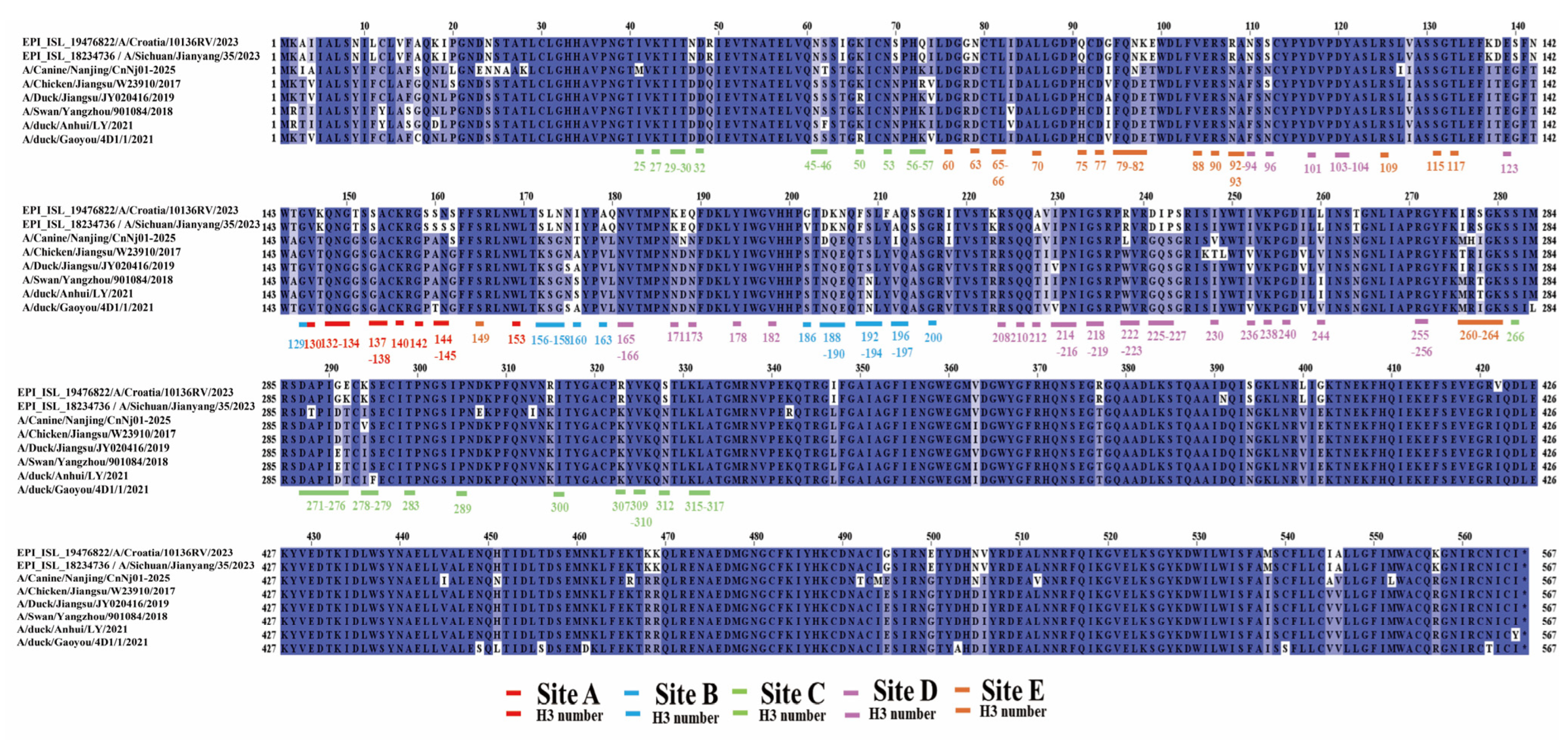

2.4. Antigen Site Analysis

2.5. Glycosylation Site Prediction and Structure Analysis

2.6. Functional Analysis of Key Residues in Genomic Segments

2.7. Hemagglutination Inhibition Assay

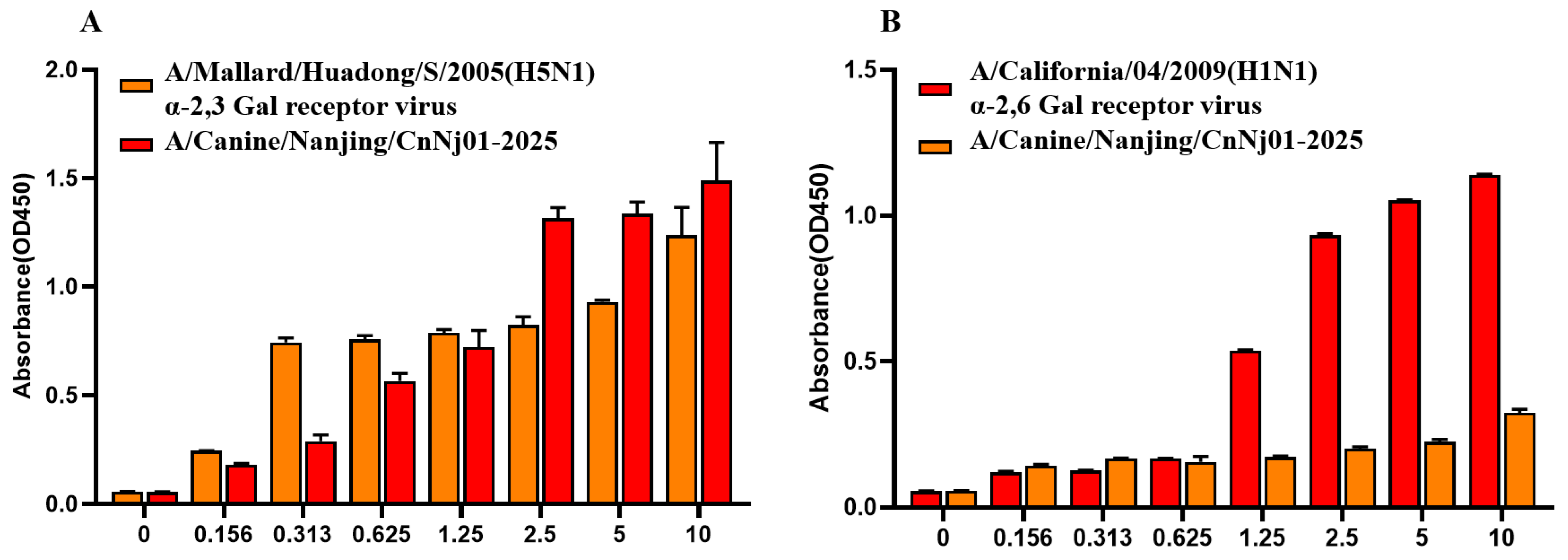

2.8. Receptor Binding Assay

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Isolation and Molecular Characterization of Canine H3N2 Influenza Virus

3.2. Phylogenetic Analysis of H3N2 Influenza Viruses Based on HA Gene Sequences

3.3. Amino Acid Comparison of Major Antigenic Sites on the HA Protein of H3N2 Viruses

3.4. Analysis of N-Linked Glycosylation Sites on the HA Protein of H3N2 Viruses

3.5. Structural Analysis of Glycosylation Patterns and Key Antigen Residues on the HA Trimer

3.6. Genome-Wide Analysis of Functional Sites in the Canine H3N2 Isolate

3.7. HI Assay Results

3.8. Receptor-Binding Properties of the Canine H3N2 Isolate

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wasik, B.R.; Damodaran, L.; Maltepes, M.A.; Voorhees, I.E.H.; Leutenegger, C.M.; Newbury, S.; Moncla, L.H.; Dalziel, B.D.; Goodman, L.B.; Parrish, C.R. The evolution and epidemiology of H3N2 canine influenza virus after 20 years in dogs. Epidemiol. Infect. 2025, 153, e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Shi, Z.; Jiao, P.; Zhang, G.; Zhong, Z.; Tian, W.; Long, L.P.; Cai, Z.; Zhu, X.; Liao, M.; et al. Avian-origin H3N2 canine influenza A viruses in Southern China. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2010, 10, 1286–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.; Kang, B.; Lee, C.; Jung, K.; Ha, G.; Kang, D.; Park, S.; Park, B.; Oh, J. Transmission of avian influenza virus (H3N2) to dogs. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2008, 14, 741–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Roy, A.; Wang, R.; Yang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Luo, W.; Shen, X.; Chen, R.A.; Irwin, D.M.; Shen, Y. Host Adaptive Evolution of Avian-Origin H3N2 Canine Influenza Virus. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 655228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, H.; Hughes, J.; Murcia, P.R. Origins and Evolutionary Dynamics of H3N2 Canine Influenza Virus. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 5406–5418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voorhees, I.E.H.; Glaser, A.L.; Toohey-Kurth, K.; Newbury, S.; Dalziel, B.D.; Dubovi, E.J.; Poulsen, K.; Leutenegger, C.; Willgert, K.J.E.; Brisbane-Cohen, L.; et al. Spread of Canine Influenza A(H3N2) Virus, United States. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2017, 23, 1950–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voorhees, I.E.H.; Dalziel, B.D.; Glaser, A.; Dubovi, E.J.; Murcia, P.R.; Newbury, S.; Toohey-Kurth, K.; Su, S.; Kriti, D.; Van Bakel, H.; et al. Multiple Incursions and Recurrent Epidemic Fade-Out of H3N2 Canine Influenza A Virus in the United States. J. Virol. 2018, 92, e00323-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Wang, R.; Zhang, C.; Wang, S.; He, W.; Zhang, J.; Liu, J.; Cai, Y.; Zhou, J.; Su, S. Genetic and evolutionary analysis of emerging H3N2 canine influenza virus. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2018, 7, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Lyu, Y.; Wu, F.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, R.; Liu, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, M.; et al. Increased public health threat of avian-origin H3N2 influenza virus caused by its evolution in dogs. Elife 2023, 12, e83470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Li, G.; Zhu, H.; Shi, W.; Wang, R.; Zhang, C.; Bi, Y.; Lai, A.; Gao, G.F.; Su, S. Emergence and adaptation of H3N2 canine influenza virus from avian influenza virus: An overlooked role of dogs in interspecies transmission. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2019, 66, 842–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Kim, E.J.; Kim, B.H.; Song, J.Y.; Cho, I.S.; Shin, Y.K. Molecular analyses of H3N2 canine influenza viruses isolated from Korea during 2013–2014. Virus Genes 2016, 52, 204–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeoung, H.-Y.; Lim, S.-I.; Shin, B.-H.; Lim, J.-A.; Song, J.-Y.; Song, D.-S.; Kang, B.-K.; Moon, H.-J.; An, D.-J. A novel canine influenza H3N2 virus isolated from cats in an animal shelter. Vet. Microbiol. 2013, 165, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; He, W.; Lu, M.; He, H.; Lai, A. Emergence and characterization of a novel reassortant canine influenza virus isolated from cats. Pathogens 2021, 10, 1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, P.; Luo, A.; Xiao, X.; Hu, X.; Shen, D.; Li, J.; Wu, X.; Xian, X.; Wei, C.; Fu, C.; et al. Serological evidence of H3N2 canine influenza virus infection among horses with dog exposure. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2019, 66, 915–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, X.; Chen, R.; Lv, Y.; Geng, J.; Guo, J.; Sun, Y.; Yang, A.; Dong, Y.; Li, M.; Deng, C.; et al. Fatal infection of a novel canine/human reassortant H3N2 influenza A virus in the zoo-housed golden monkeys. Vet. Microbiol. 2025, 2025, 110792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Song, D.; Lyoo, K.-S. Mammalian adaptation and zoonotic risk of influenza A viruses in companion animals. J. Vet. Sci. 2025, 26, e80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Sobrido, L.; Blanco-Lobo, P.; Rodriguez, L.; Fitzgerald, T.; Zhang, H.; Nguyen, P.; Anderson, C.S.; Holden-Wiltse, J.; Bandyopadhyay, S.; Nogales, A.; et al. Characterizing Emerging Canine H3 Influenza Viruses. PLoS Pathog. 2020, 16, e1008409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.-H.; Huang, I.-T.; Wu, R.-C.; Chen, L.-K. A highly efficient and accurate method of detecting and subtyping Influenza A pdm H1N1 and H3N2 viruses with newly emerging mutations in the matrix gene in Eastern Taiwan. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0283074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, E.; Neumann, G.; Kawaoka, Y.; Hobom, G.; Webster, R.G. A DNA transfection system for generation of influenza A virus from eight plasmids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 6108–6113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auewarakul, P.; Suptawiwat, O.; Kongchanagul, A.; Sangma, C.; Suzuki, Y.; Ungchusak, K.; Louisirirotchanakul, S.; Lerdsamran, H.; Pooruk, P.; Thitithanyanont, A.; et al. An avian influenza H5N1 virus that binds to a human-type receptor. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 9950–9955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, S.; Jiang, Y.; Huang, K.; Huang, J.; Yang, D.; Zhu, J.; Zhu, Y.; Shi, S.; Peng, D.; et al. Hemagglutinin glycosylation modulates the pathogenicity and antigenicity of the H5N1 avian influenza virus. Vet. Microbiol. 2015, 175, 244–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cueno, M.E.; Shiotsu, H.; Nakano, K.; Sugiyama, E.; Kikuta, M.; Usui, R.; Oya, R.; Imai, K. Structural significance of residues 158-160 in the H3N2 hemagglutnin globular head: A computational study with implications in viral evolution and infection. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2019, 89, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popova, L.; Smith, K.; West, A.H.; Wilson, P.C.; James, J.A.; Thompson, L.F.; Air, G.M. Immunodominance of antigenic site B over site A of hemagglutinin of recent H3N2 influenza viruses. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e41895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beer, K.; Dai, M.; Howell, S.; Rijal, P.; Townsend, A.R.; Lin, Y.; Wharton, S.A.; Daniels, R.S.; McCauley, J.W. Characterization of neutralizing epitopes in antigenic site B of recently circulating influenza A(H3N2) viruses. J. Gen. Virol. 2018, 99, 1001–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koel, B.F.; Burke, D.F.; Bestebroer, T.M.; van der Vliet, S.; Zondag, G.C.; Vervaet, G.; Skepner, E.; Lewis, N.S.; Spronken, M.I.; Russell, C.A.; et al. Substitutions near the receptor binding site determine major antigenic change during influenza virus evolution. Science 2013, 342, 976–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luczo, J.M.; Spackman, E. Epitopes in the HA and NA of H5 and H7 avian influenza viruses that are important for antigenic drift. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2024, 48, fuae014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, E.; Long, L.P.; Zhao, N.; Hall, J.S.; Baroch, J.A.; Nolting, J.; Senter, L.; Cunningham, F.L.; Pharr, G.T.; Hanson, L.; et al. Antigenic Characterization of H3 Subtypes of Avian Influenza A Viruses from North America. Avian Dis. 2016, 60, 346–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.P.; Xiong, X.; Wharton, S.A.; Martin, S.R.; Coombs, P.J.; Vachieri, S.G.; Christodoulou, E.; Walker, P.A.; Liu, J.; Skehel, J.J.; et al. Evolution of the receptor binding properties of the influenza A(H3N2) hemagglutinin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 21474–21479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaji, R.; Yamada, S.; Le, M.Q.; Li, C.; Chen, H.; Qurnianingsih, E.; Nidom, C.A.; Ito, M.; Sakai-Tagawa, Y.; Kawaoka, Y. Identification of PB2 mutations responsible for the efficient replication of H5N1 influenza viruses in human lung epithelial cells. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 3947–3956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Sun, Y.; Xu, Q.; Tan, Y.; Pu, J.; Yang, H.; Brown, E.G.; Liu, J. Mouse-adapted H9N2 influenza A virus PB2 protein M147L and E627K mutations are critical for high virulence. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e40752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Zu, Z.; Liu, J.; Song, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, C.; Liu, L.; Tong, Q.; Wang, M.; Sun, H.; et al. Prevailing I292V PB2 mutation in avian influenza H9N2 virus increases viral polymerase function and attenuates IFN-beta induction in human cells. J. Gen. Virol. 2019, 100, 1273–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehle, A.; Doudna, J.A. Adaptive strategies of the influenza virus polymerase for replication in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 21312–21316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subbarao, E.K.; London, W.; Murphy, B.R. A single amino acid in the PB2 gene of influenza A virus is a determinant of host range. J. Virol. 1993, 67, 1761–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, R.W.; Chen, G.W.; Sung, H.H.; Lin, R.J.; Yen, L.C.; Tseng, Y.L.; Chang, Y.K.; Lien, S.P.; Shih, S.R.; Liao, C.L. Naturally occurring mutations in PB1 affect influenza A virus replication fidelity, virulence, and adaptability. J. Biomed. Sci. 2019, 26, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamaji, R.; Yamada, S.; Le, M.Q.; Ito, M.; Sakai-Tagawa, Y.; Kawaoka, Y. Mammalian adaptive mutations of the PA protein of highly pathogenic avian H5N1 influenza virus. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 4117–4125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Xu, J.; Shi, J.; Li, Y.; Chen, H. Synergistic Effect of S224P and N383D Substitutions in the PA of H5N1 Avian Influenza Virus Contributes to Mammalian Adaptation. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 10510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Feng, Z.; Chen, Y.; Yang, L.; Liu, J.; Li, X.; Liu, S.; Zhou, L.; Wei, H.; Gao, R.; et al. Mammalian-adaptive mutation NP-Q357K in Eurasian H1N1 Swine Influenza viruses determines the virulence phenotype in mice. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2019, 8, 989–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, D.; Xue, R.; Zhang, M.; Lu, C.; Ma, T.; Ren, C.; Zhang, T.; Yang, J.; Teng, Q.; Li, X.; et al. N-Linked Glycosylation Plays an Important Role in Budding of Neuraminidase Protein and Virulence of Influenza Viruses. J. Virol. 2021, 95, e02042-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naguib, M.M.; Hagag, N.; El-Sanousi, A.A.; Hussein, H.A.; Arafa, A.S. The matrix gene of influenza A H5N1 in Egypt, 2006-2016: Molecular insights and distribution of amantadine-resistant variants. Virus Genes 2016, 52, 872–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kainov, D.E.; Muller, K.H.; Theisen, L.L.; Anastasina, M.; Kaloinen, M.; Muller, C.P. Differential effects of NS1 proteins of human pandemic H1N1/2009, avian highly pathogenic H5N1, and low pathogenic H5N2 influenza A viruses on cellular pre-mRNA polyadenylation and mRNA translation. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 7239–7247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo, B.; Choi, J.M.; Bornholdt, Z.A.; Sankaran, B.; Rice, A.P.; Prasad, B.V. The influenza A virus protein NS1 displays structural polymorphism. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 4113–4122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, N.S.; Anderson, T.K.; Kitikoon, P.; Skepner, E.; Burke, D.F.; Vincent, A.L. Substitutions near the hemagglutinin receptor-binding site determine the antigenic evolution of influenza A H3N2 viruses in U.S. swine. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 4752–4763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.R.; Liu, Y.M.; Tseng, Y.C.; Ma, C. Better influenza vaccines: An industry perspective. J. Biomed. Sci. 2020, 27, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, Y.; Suzuki, Y. Evidence for N-glycan shielding of antigenic sites during evolution of human influenza A virus hemagglutinin. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 3446–3451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, K.C.; Galloway, S.E.; Lasanajak, Y.; Song, X.; Heimburg-Molinaro, J.; Yu, H.; Chen, X.; Talekar, G.R.; Smith, D.F.; Cummings, R.D.; et al. Analysis of influenza virus hemagglutinin receptor binding mutants with limited receptor recognition properties and conditional replication characteristics. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 12387–12398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.R.; Hensley, S.E.; David, A.; Schmidt, L.; Gibbs, J.S.; Puigbo, P.; Ince, W.L.; Bennink, J.R.; Yewdell, J.W. Fitness costs limit influenza A virus hemagglutinin glycosylation as an immune evasion strategy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, E1417–E1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ushirogawa, H.; Naito, T.; Tokunaga, H.; Tanaka, T.; Nakano, T.; Terada, K.; Ohuchi, M.; Saito, M. Re-emergence of H3N2 strains carrying potential neutralizing mutations at the N-linked glycosylation site at the hemagglutinin head, post the 2009 H1N1 pandemic. BMC Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.C.; Wilson, I.A. Influenza Hemagglutinin Structures and Antibody Recognition. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2020, 10, a038778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigeveno, R.M.; Han, A.X.; de Vries, R.P.; Parker, E.; de Haan, K.; van Leeuwen, S.; Hulme, K.D.; Lauring, A.S.; Velthuis, A.J.W.T.; Boons, G.-J.; et al. Long-term evolution of human seasonal influenza virus A(H3N2) is associated with an increase in polymerase complex activity. Virus Evol. 2024, 10, veae030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.M.; Huddleston, J.; Doud, M.B.; Hooper, K.A.; Wu, N.C.; Bedford, T.; Bloom, J.D. Deep mutational scanning of hemagglutinin helps predict evolutionary fates of human H3N2 influenza variants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E8276–E8285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, H.; Xiao, B.; Lin, X.; Liang, Z.; Ling, S.; Bai, Y.; Dhanasekaran, V.; Song, W.; Wong, S.-S.; Zanin, M. Chronology of H3N2 human influenza virus surface glycoprotein adaptation from 1968 to 2019 reveals a surge of adaptation between 1997 and 2002. J. Virol. 2025, 99, e0132925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.C.; Thompson, A.J.; Xie, J.; Lin, C.-W.; Nycholat, C.M.; Zhu, X.; Lerner, R.A.; Paulson, J.C.; Wilson, I.A. A complex epistatic network limits the mutational reversibility in the influenza hemagglutinin receptor-binding site. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Carney, P.J.; Chang, J.C.; Guo, Z.; Villanueva, J.M.; Stevens, J. Structure and receptor binding preferences of recombinant human A(H3N2) virus hemagglutinins. Virology 2015, 477, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, R.; Liang, W.; Ouyang, W.O.; Garcia, A.H.; Kikuchi, C.; Wang, S.; McBride, R.; Tan, T.J.C.; Sun, Y.; Chen, C.; et al. Epistasis mediates the evolution of the receptor binding mode in recent human H3N2 hemagglutinin. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 5175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soh, Y.S.; Moncla, L.H.; Eguia, R.; Bedford, T.; Bloom, J.D. Comprehensive mapping of adaptation of the avian influenza polymerase protein PB2 to humans. Elife 2019, 8, e45079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Strain Name | Abbreviation | Host | Collection Date | Geographic Origin | GenBank/GISAID Accession No. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A/Croatia/l0136RV/2023 | H1 | Human | 2023 | Croatia | EPI_ISL_19476822 |

| A/Sichuan/Jianyang/35/2023 | H2 | Human | 2023 | Sichuan, China | EPI2735848-EPI2735855 |

| A/Canine/Nanjing/CnNj01-2025 | C1 | Canine | March 2025 | Nanjing, Jiangsu, China | PX474832-PX474839 |

| A/Chicken/Jiangsu/W23910/2017 | A1 | Avian (Chicken) | 2017 | Jiangsu, China | PV124747-PV124754 |

| A/Duck/Jiangsu/JY020416/2019 | A2 | Avian (Duck) | 2019 | Jiangsu, China | PV124763-PV124770 |

| A/Swan/Yangzhou/901084/2018 | A3 | Avian (Swan) | 2018 | Yangzhou, Jiangsu, China | PV124739-PV124746 |

| A/Duck/Anhui/LY/2021 | A4 | Avian (Duck) | 2021 | Anhui, China | PV124795-PV124802 |

| A/Duck/Gaoyou/4D1/1/2021 | A5 | Avian (Duck) | 2021 | Gaoyou, Jiangsu, China | PV124803-PV124810 |

| HA/H3 Number | H1 | H2 | C1 | A1 | A2 | A3 | A4 | A5 | Phenotype | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site B | 176/160 | I | I | T | A | A | S | S | A | Affected the amino acid orientation at residue 158 [22,23] |

| 204/188 | D | D | D | N | N | N | N | N | Close to key antigenic site and receptor binding site 205/189 [24,25] | |

| 212/196 | A | A | I | V | V | V | V | V | Important for antigenic drift [26] | |

| Site C | 61/45 | N | N | N | S | S | N | S | S | Site C [27] |

| Site D | 237/222 | R | R | L | W | W | W | W | W | The mutation at site 222 directly impacts viral fitness and antigenicity [28] |

| Site E | 97/81 | N | N | N | D | D | D | D | D | D81N influences antigenic drift and generates glycosylation only in CIV [28] |

| HA/H3 Number | 18/ 2 | 22/ 6 | 24/ 8 | 38/ 22 | 54/ 38 | 61/ 45 | 79/ 63 | 97/ 81 | 110 /94 | 142 /126 | 149 /129 | 181 /165 | 262 /246 | 301 /285 | 499 /483 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| H2 | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| C1 | − | − | − | + | + | + | − | + | − | − | − | + | − | + | + |

| A1 | − | + | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | + |

| A2 | + | + | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | + |

| A3 | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | + |

| A4 | − | + | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | + |

| A5 | − | + | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | + |

| Residues | H2 | C1 | A1 | A2 | A3 | A4 | A5 | Phenotype | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PB2 | 147 | I | T | I | I | I | I | I | I147T is critical for high virulence in mammals [29,30] |

| 292 | T | T | I | I | I | I | I | I292T increases viral polymerase in H9N2 [31] | |

| 590 | S | S | G | G | G | G | G | G590S is adaptation marker in H1N1 [32] | |

| 627 | K | E | E | E | E | E | E | E627K is determinant of host range [33] | |

| PB1 | 216 | G | N | S | S | S | S | N | G216S shows higher virulence in mammal [34] |

| PA | 241 | C | Y | C | C | C | C | C | C241Y and other sites markedly enhanced virus growth in the lung tissue of mice [35] |

| 383 | N | D | D | D | D | D | D | N383D substitutions contribute to mammalian adaptation [36] | |

| 573 | V | I | I | I | I | I | I | I573V and other sites markedly enhanced virus growth in the lung tissue of mice [35] | |

| NP | 313 | Y | F | F | F | F | F | F | |

| 357 | K | Q | Q | Q | Q | Q | Q | Q357K determines the virulence phenotype in mice [37] | |

| NA | 367–369 | NET | SKD | SKD | SKD | SKD | SKD | SKD | N367 is an N-linked glycosylation site [38] |

| 402–403 | DR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | N402 is an N-linked glycosylation site [38] | |

| M1 | 15 | V | I | V | I | V | V | V | The V15I mutation in H5N1 virus is associated with enhanced virulence [39] |

| NS1 | 67 | K | W | R | R | R | R | R | R67W is related to viral host adaptability and virulence [40] |

| 75 | E | K | E | E | E | E | E | Participates in the formation of type I β-turn [41] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Peng, J.; Miao, X.; Zhang, X.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Liu, G.; Na, L.; Xu, N.; Peng, D. Molecular Characterization of an H3N2 Canine Influenza Virus Isolated from a Dog in Jiangsu, China, in 2025. Vet. Sci. 2026, 13, 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci13010032

Peng J, Miao X, Zhang X, Li Z, Wang Y, Liu G, Na L, Xu N, Peng D. Molecular Characterization of an H3N2 Canine Influenza Virus Isolated from a Dog in Jiangsu, China, in 2025. Veterinary Sciences. 2026; 13(1):32. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci13010032

Chicago/Turabian StylePeng, Jingwen, Xinyu Miao, Xinyi Zhang, Zhifan Li, Yiling Wang, Guofang Liu, Lei Na, Nuo Xu, and Daxin Peng. 2026. "Molecular Characterization of an H3N2 Canine Influenza Virus Isolated from a Dog in Jiangsu, China, in 2025" Veterinary Sciences 13, no. 1: 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci13010032

APA StylePeng, J., Miao, X., Zhang, X., Li, Z., Wang, Y., Liu, G., Na, L., Xu, N., & Peng, D. (2026). Molecular Characterization of an H3N2 Canine Influenza Virus Isolated from a Dog in Jiangsu, China, in 2025. Veterinary Sciences, 13(1), 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci13010032