Effects of Dandelion Extracts on the Ruminal Microbiota, Metabolome, and Systemic Inflammation in Dairy Goats Fed a High-Concentrate Diet

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

2.2. Animal and Design of Experiments

2.3. Sample Collection and Assessment

2.4. Assessment of Flavonoid Contents from Dandelion Extracts

2.5. Assessment of Ruminal Fluid VFA and LPS

2.6. Assessments of Serum Immune Indicators and Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines

2.7. RNA Extraction and Assessment of Gene Expression for Inflammatory Indicators

2.8. S Ribosomal RNA Gene Sequencing

2.9. Assessment of Metabolome

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

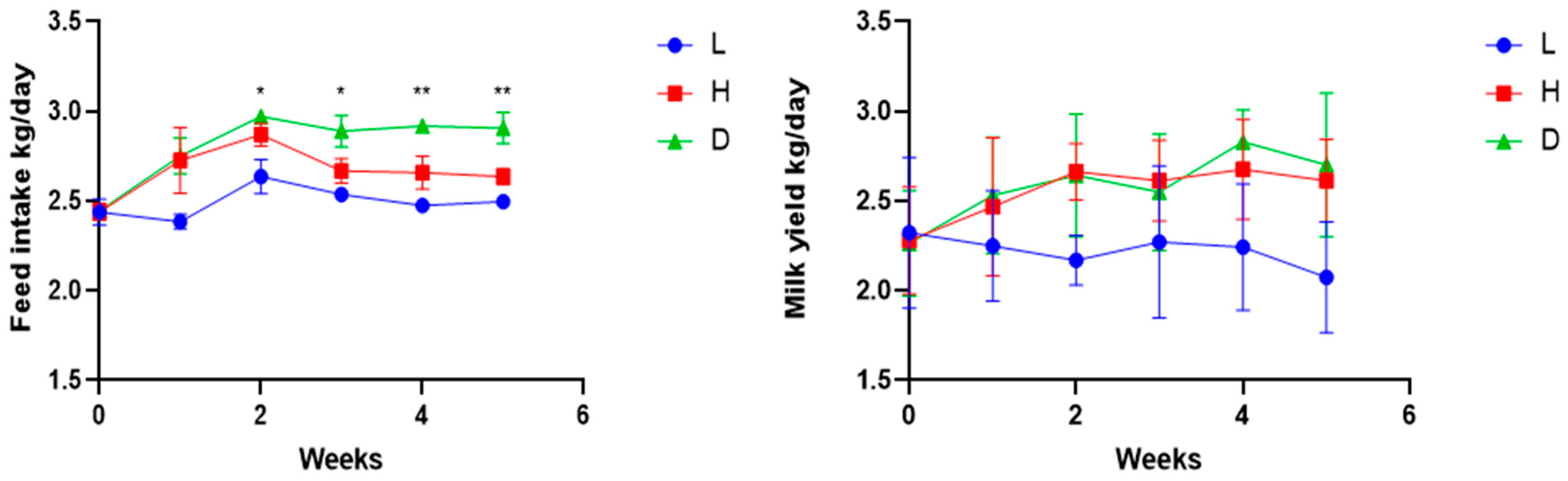

3.1. Influence of Various Feeds on Feed Intake, Milk Yield, and Milk Quality in Dairy Goats

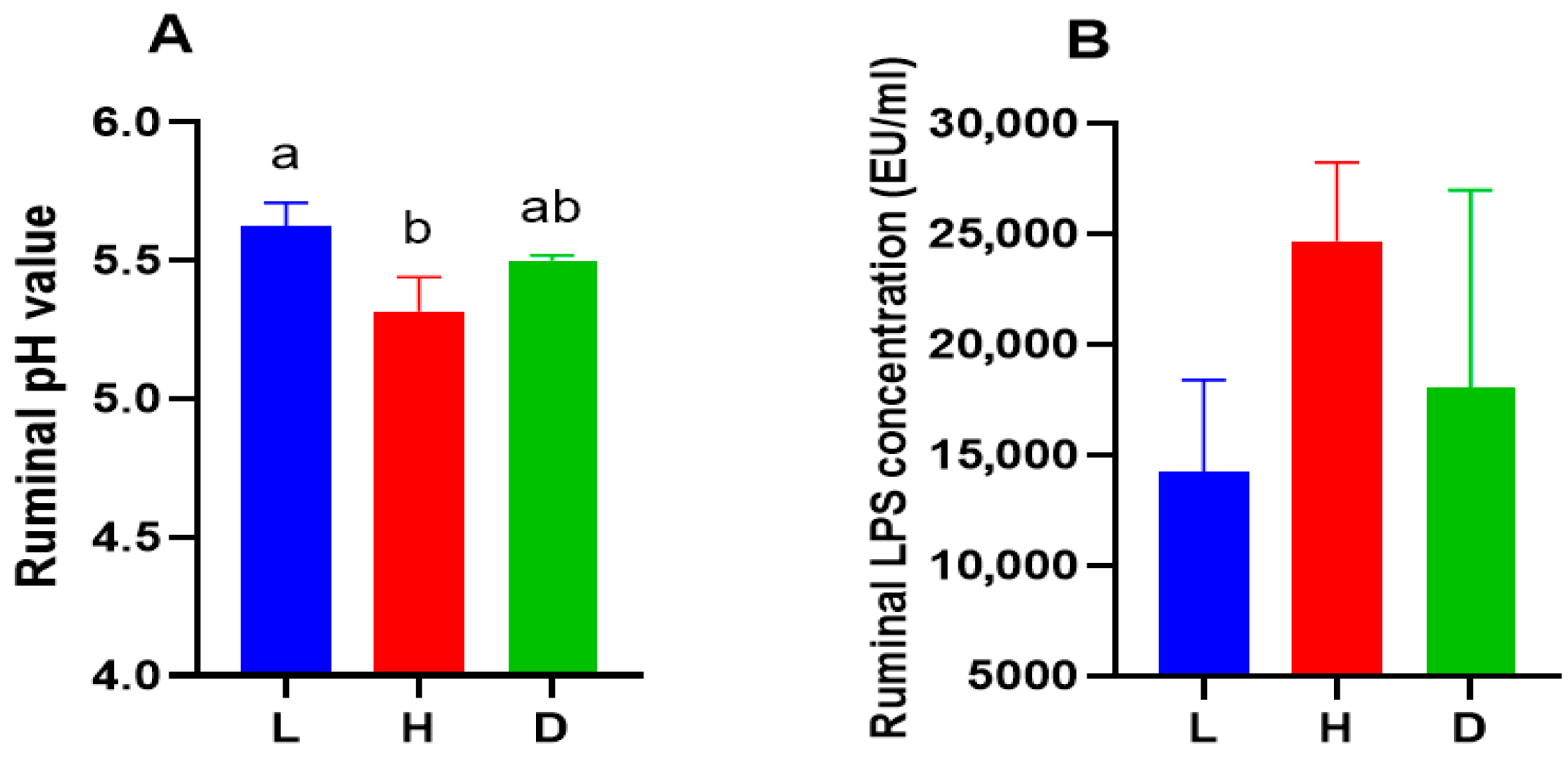

3.2. Influence of Various Feeds on Ruminal pH, Ruminal LPS Concentrations, and Ruminal Fermentation Parameters in Dairy Goats

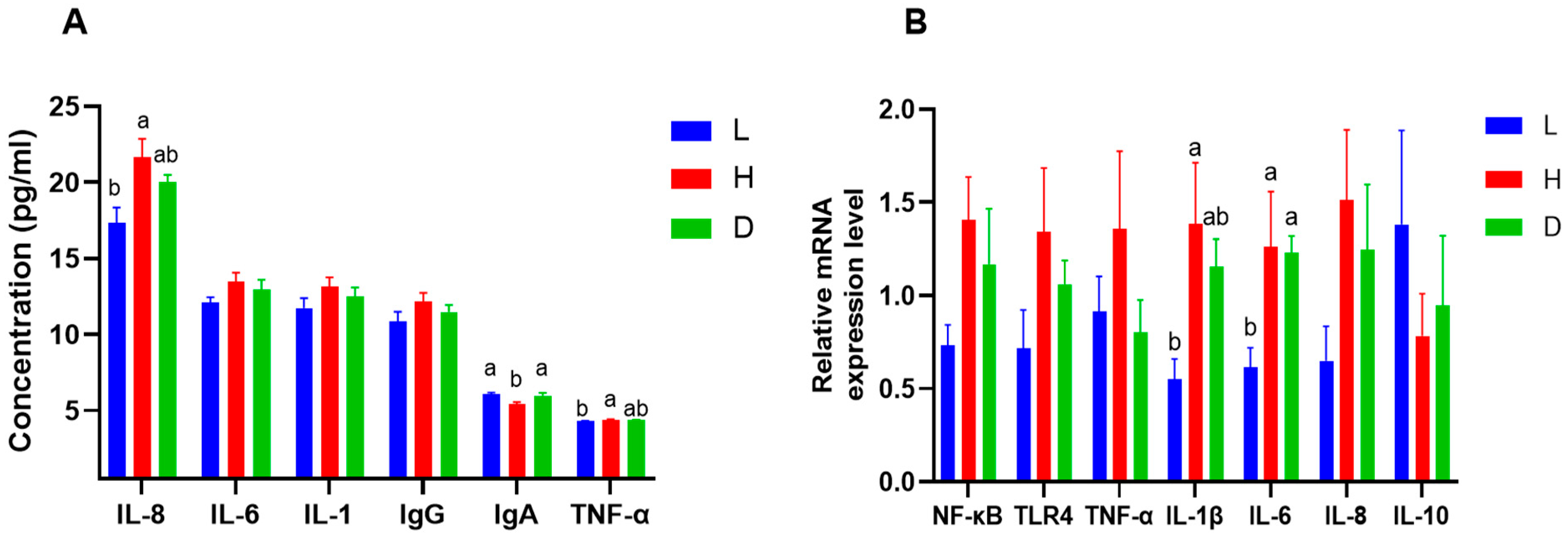

3.3. Influence of Various Feeds on Serum Immunoglobulin, Serum Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines, and the Expression of a Gene Linked to Inflammation in Dairy Goats

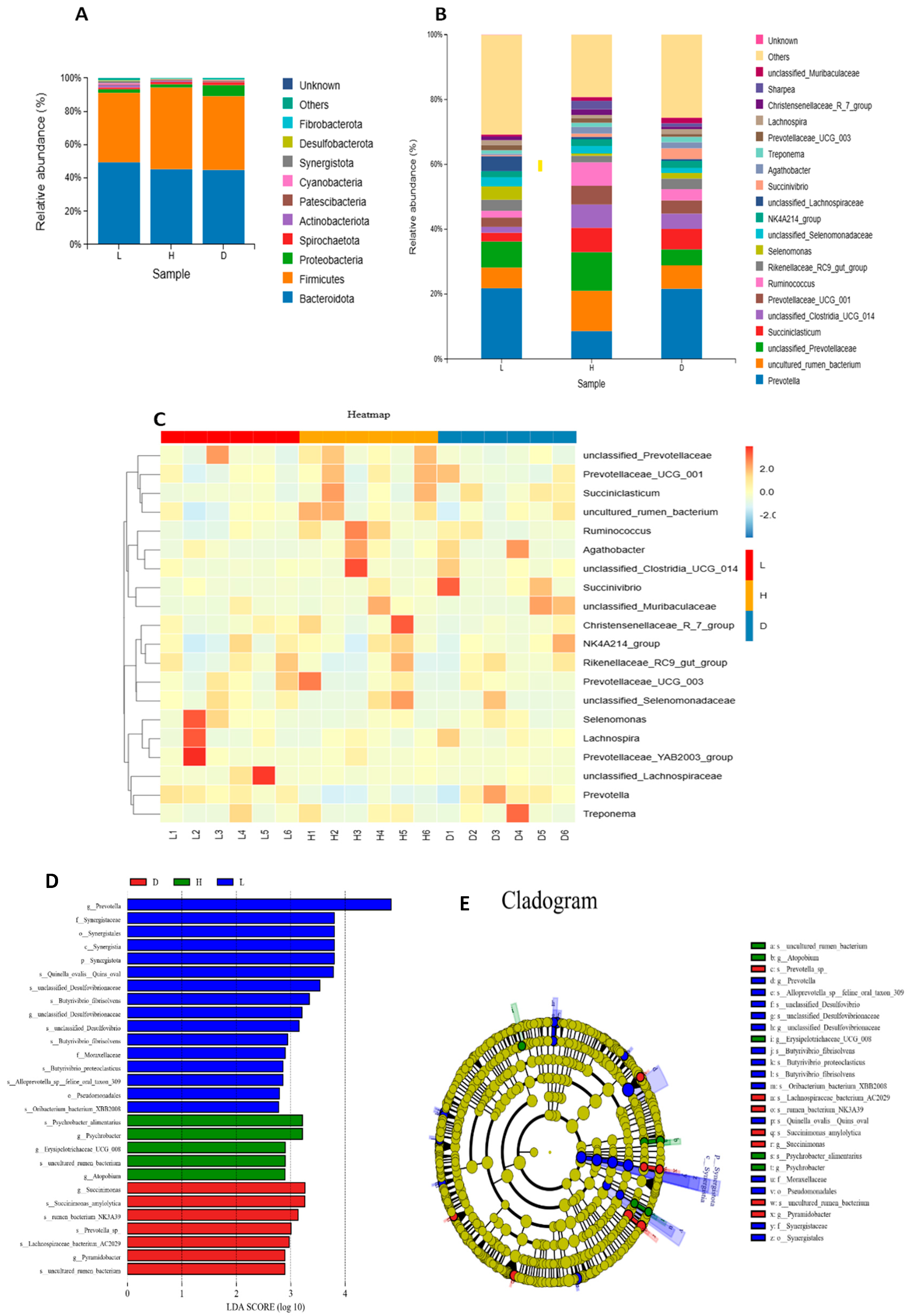

3.4. Effect of Diets on Ruminal Microbial Composition in Dairy Goat

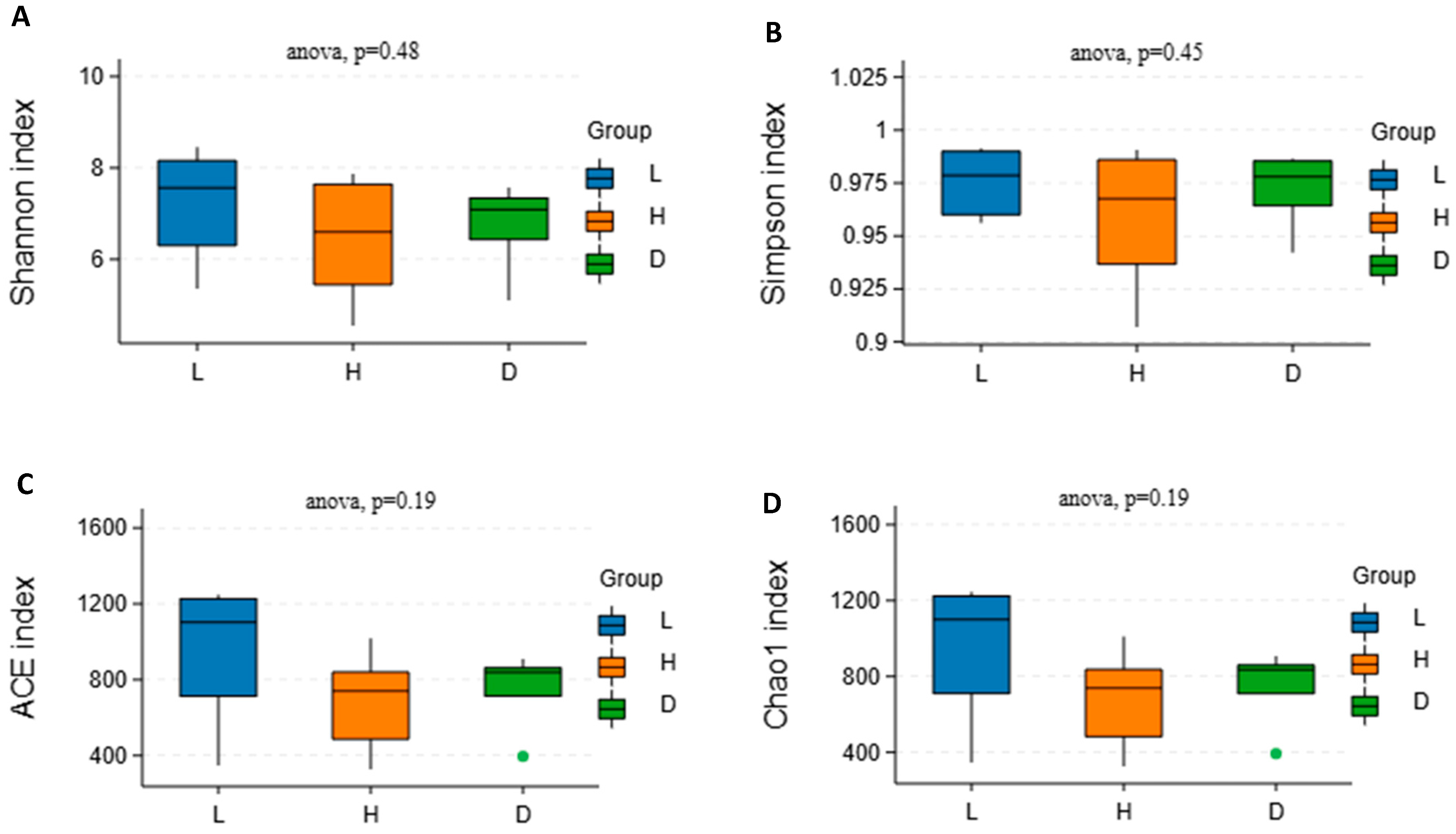

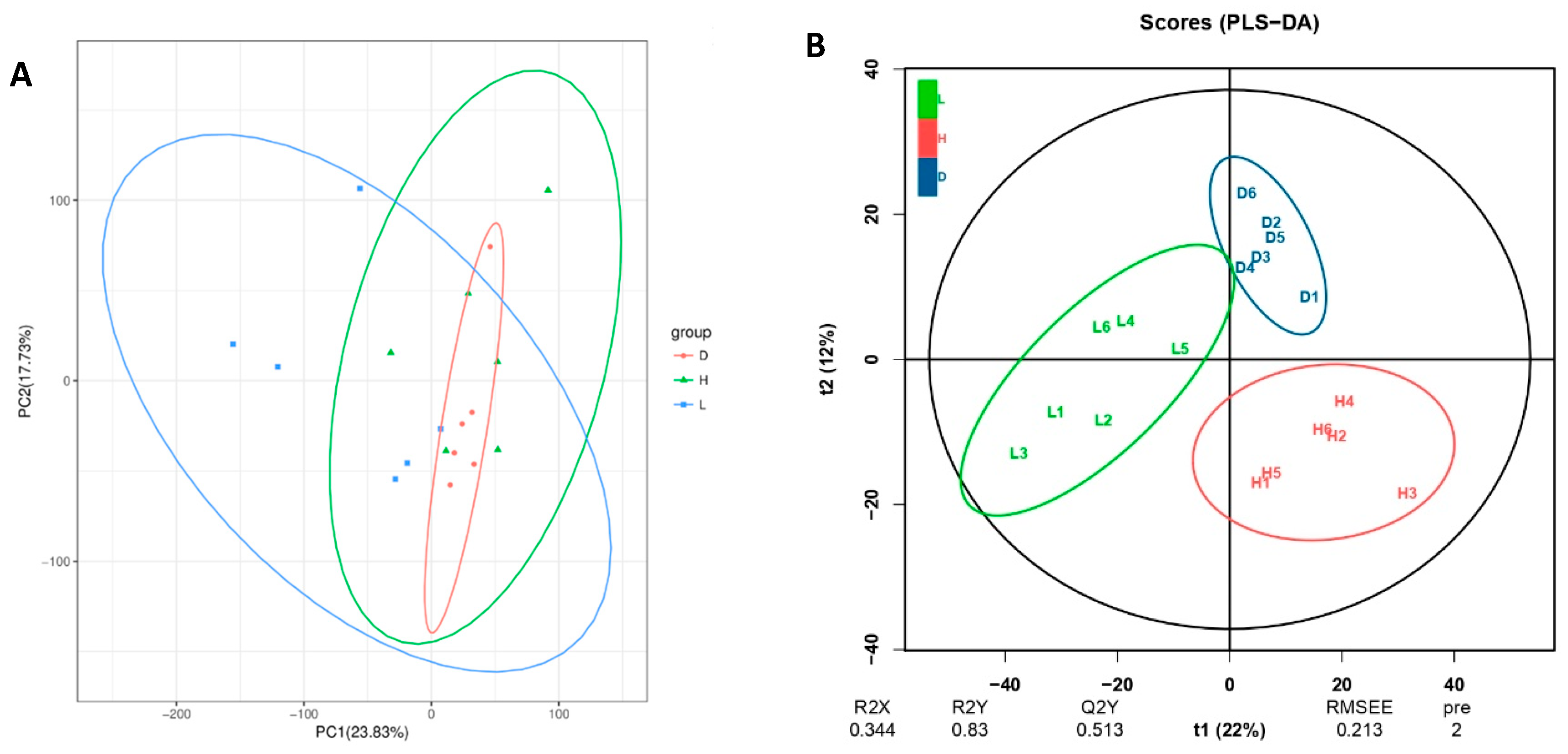

3.5. Influence of Various Feeds on Alpha Diversity and Beta Diversity of the Microbial Community in Dairy Goats

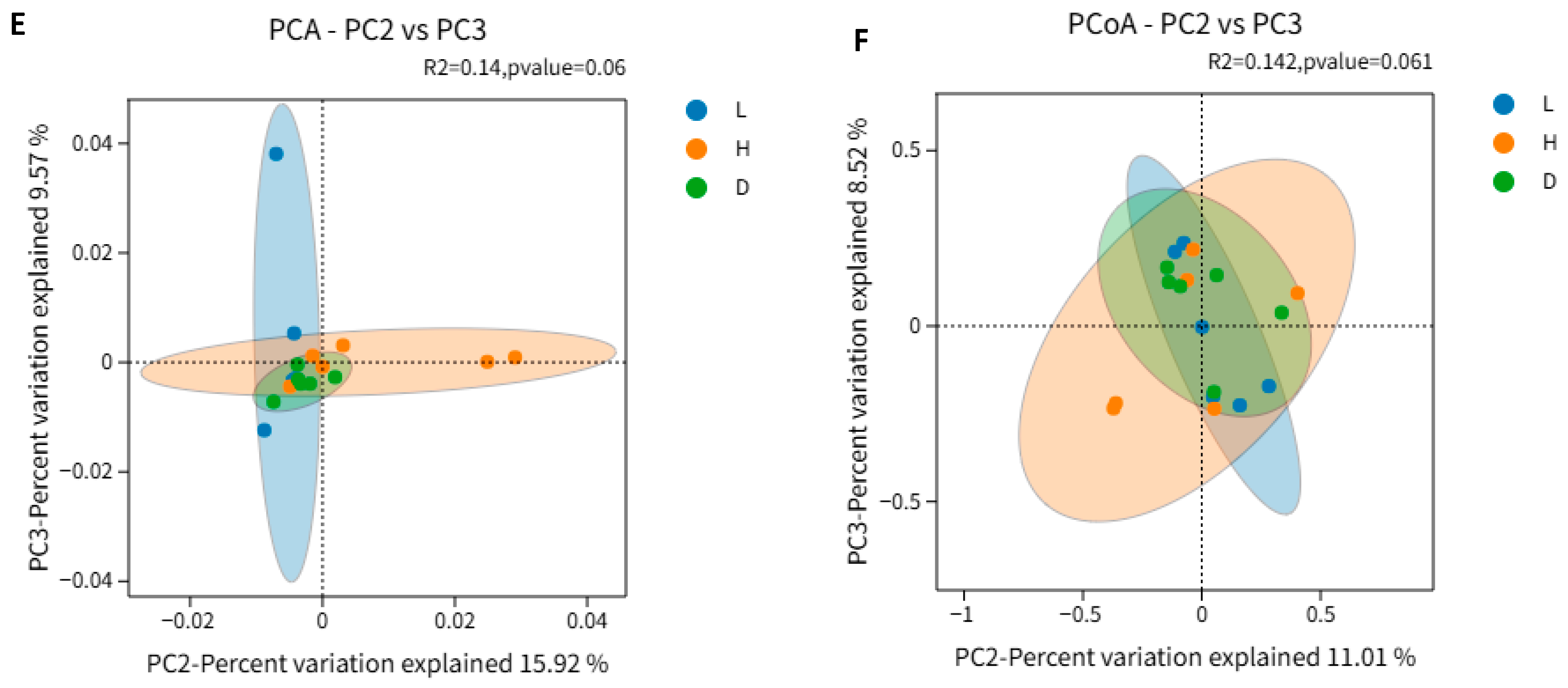

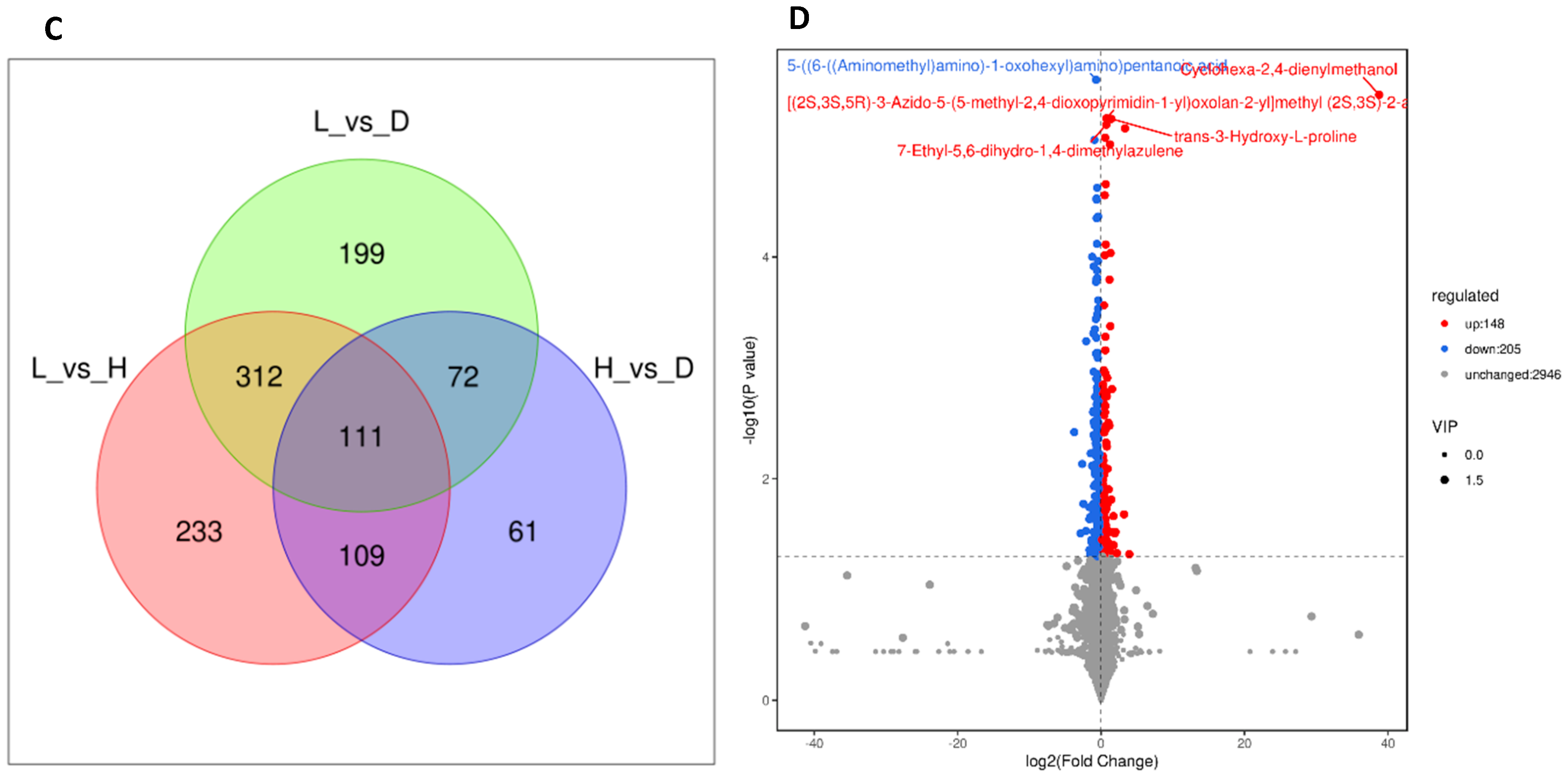

3.6. Influence of Various Feeds on Dairy Goat Rumen Fluid Metabolites

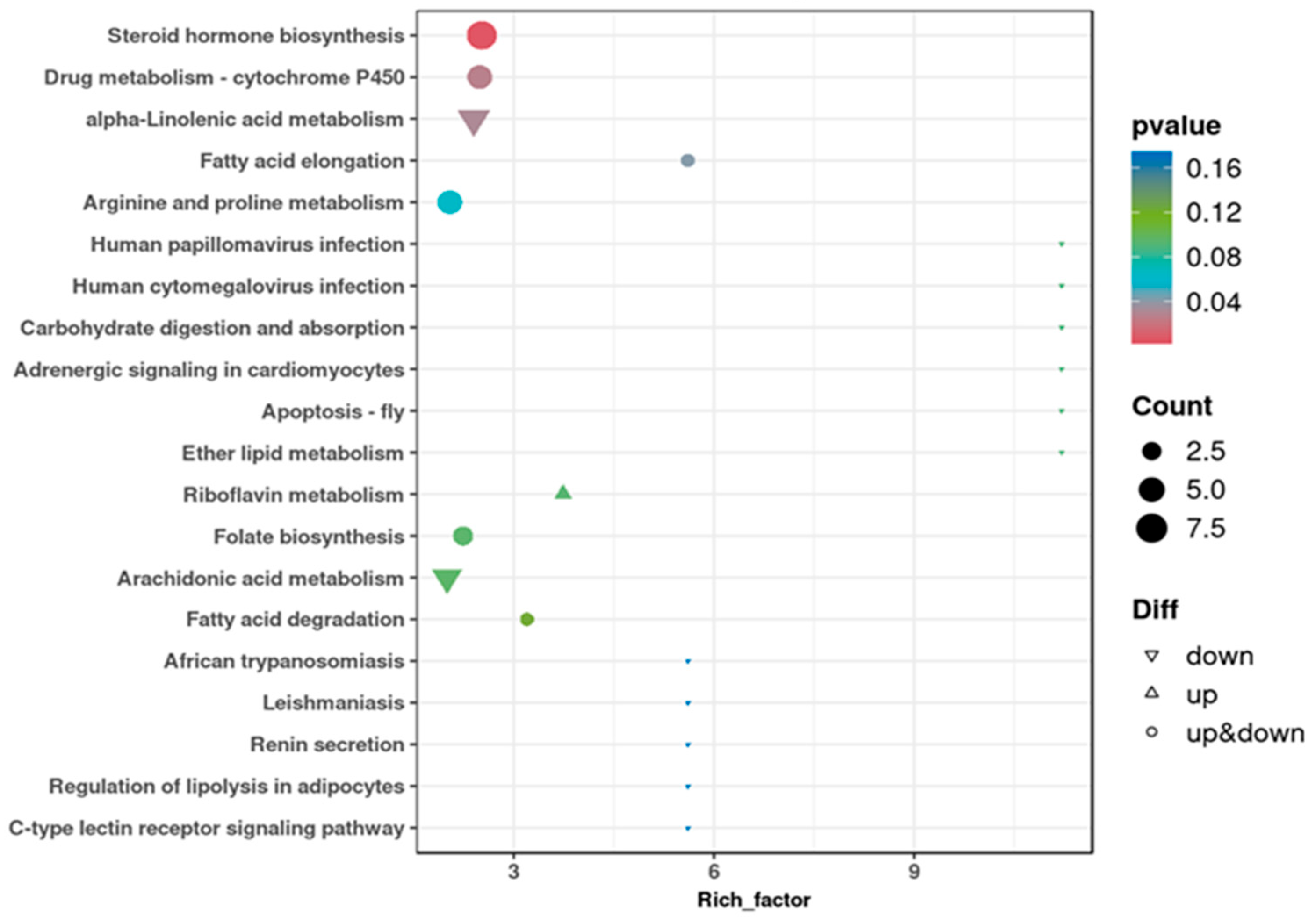

3.7. Differential Metabolite Enrichment Analysis in KEGG Pathways

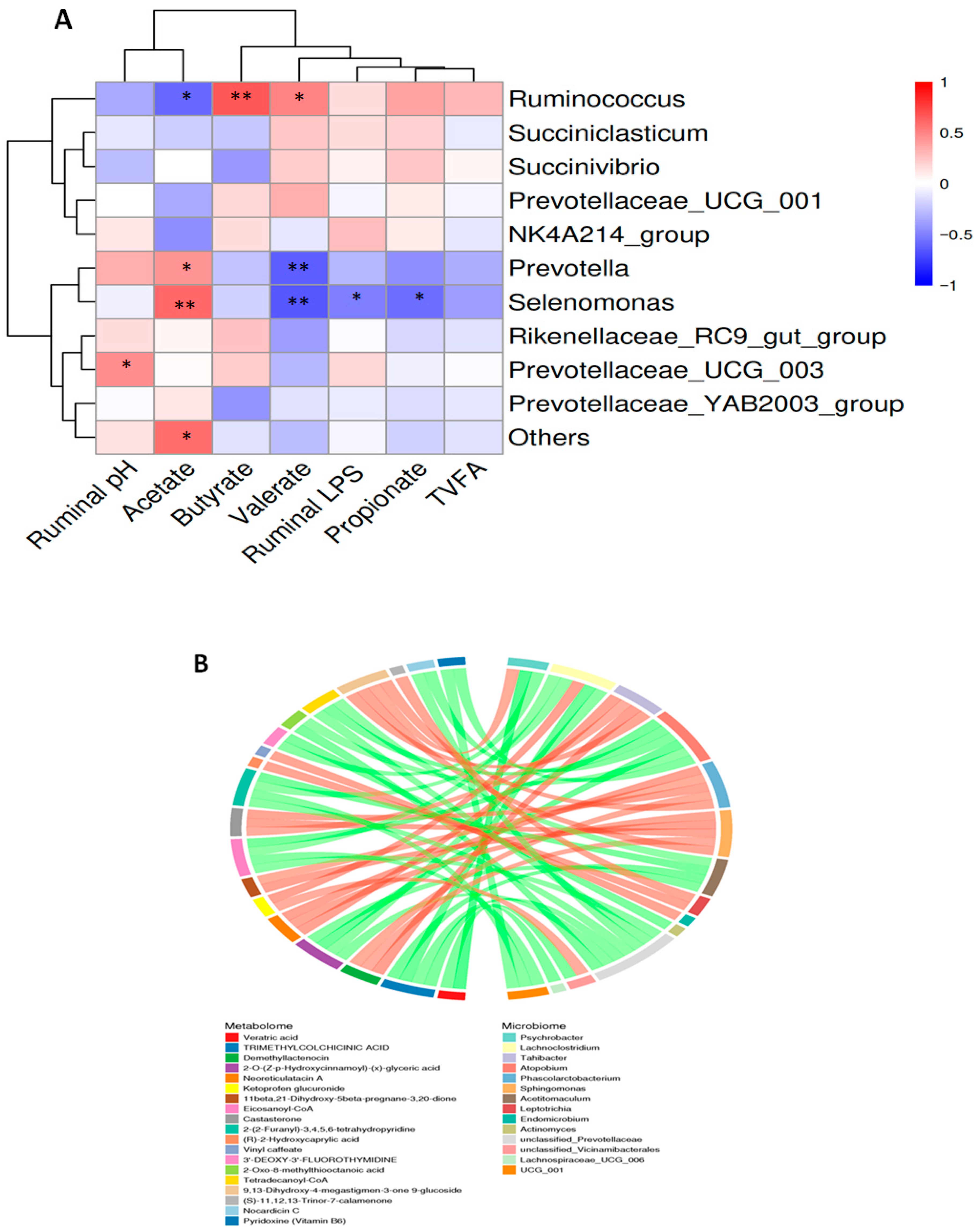

3.8. Correlation Analysis Between the Ruminal Fluid Parameters, Microbiome, and Metabolome in Dairy Goats

4. Discussion

4.1. Influence of Various Feeds on Feed Intake, Milk Yield, and Milk Quality in Dairy Goats

4.2. Influence of Various Feeds on Ruminal pH, Ruminal LPS Concentrations, and Ruminal Fermentation Parameters in Dairy Goats

4.3. Influence of Various Feeds on Serum Immunoglobulin, Serum Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines, and the Expression of a Gene Linked to Inflammation in Dairy Goats

4.4. Influence of Various Feeds on Ruminal Microbial Composition in Dairy Goat

4.5. Influence of Various Feeds on Alpha Diversity and Beta Diversity of the Microbial Community in Dairy Goats

4.6. Influence of Various Feeds on Dairy Goat Rumen Fluid Metabolites

4.7. Differential Metabolite Enrichment Analysis in KEGG Pathways

4.8. Correlation Analysis Between the Ruminal Fluid Parameters, Microbiome, and Metabolome in Dairy Goats

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Șonea, C.; Gheorghe-Irimia, R.A.; Dulaimi, M.K.H.A.; Udrea, L.; Tăpăloagă, D.; Tăpăloagă, P.-R. Optimizing Feed Formulation Strategies for Attaining Optimal Nutritional Balance in High-Performing Dairy Goats in Intensive Farming Production Systems. Ann. Valahia Univ. Târgovişte Agric. 2024, 16, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giger-Reverdin, S. Recent Advances in the Understanding of Subacute Ruminal Acidosis (SARA) in Goats, with Focus on the Link to Feeding Behaviour. Small Rumin. Res. 2018, 163, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, H.F.; Faciola, A.P. Ruminal Acidosis, Bacterial Changes, and Lipopolysaccharides. J. Anim. Sci. 2020, 98, skaa248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, D.; Chang, G.; Zhang, K.; Guo, J.; Xu, T.; Shen, X. Rumen-Derived Lipopolysaccharide Enhances the Expression of Lingual Antimicrobial Peptide in Mammary Glands of Dairy Cows Fed a High-Concentrate Diet. BMC Vet. Res. 2016, 12, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cochet, F.; Peri, F. The Role of Carbohydrates in the Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)/Toll-Like Receptor 4 (TLR4) Signalling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuñez, A.J.C.; Caetano, M.; Berndt, A.; Demarchi, J.J.A.D.A.; Leme, P.R.; Lanna, D.P.D. Combined Use of Ionophore and Virginiamycin for Finishing Nellore Steers Fed High Concentrate Diets. Sci. Agric. 2013, 70, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Xie, Y. A Systematic Review on Antibiotics Misuse in Livestock and Aquaculture and Regulation Implications in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 798, 149205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michalak, M.; Wojnarowski, K.; Cholewińska, P.; Szeligowska, N.; Bawej, M.; Pacoń, J. Selected Alternative Feed Additives Used to Manipulate the Rumen Microbiome. Animals 2021, 11, 1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chagas, M.D.S.S.; Behrens, M.D.; Moragas-Tellis, C.J.; Penedo, G.X.M.; Silva, A.R.; Gonçalves-de-Albuquerque, C.F. Flavonols and Flavones as Potential Anti-Inflammatory, Antioxidant, and Antibacterial Compounds. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 9966750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paniagua, M.; Crespo, J.; Arís, A.; Devant, M. Citrus Aurantium Flavonoid Extract Improves Concentrate Efficiency, Animal Behavior, and Reduces Rumen Inflammation of Holstein Bulls Fed High-Concentrate Diets. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2019, 258, 114304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q.; Xing, Q.; Liu, Z.; Zou, Y.; Liu, X.; Xia, H. The Phytochemical and Pharmacological Profile of Dandelion. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 179, 117334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Mgeni, M.; Xiu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Chen, J.; Sun, Y. Effects of Dandelion Extract on Promoting Production Performance and Reducing Mammary Oxidative Stress in Dairy Cows Fed High-Concentrate Diet. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Jo, Y.; Jeong, S.; Kim, Y.; Han, J. An Investigation of Antioxidative and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Taraxacum Coreanum (White Dandelion) in Lactating Holstein Dairy Cows. J. Adv. Vet. Anim. Res. 2024, 11, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lv, M.; Wang, J.; Tian, Z.; Yu, B.; Wang, B.; Liu, J.; Liu, H. Dandelion (Taraxacum Mongolicum Hand.-Mazz.) Supplementation-Enhanced Rumen Fermentation through the Interaction between Ruminal Microbiome and Metabolome. Microorganisms 2020, 9, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Research Council. Nutrient Requirements of Small Ruminants: Sheep, Goats, Cervids, and New World Camelids; Animal Nutrition Series; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-0-309-10213-1. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Dong, G.; Ao, C.; Zhang, S.; Qiu, M.; Wang, X.; Wu, Y.; Erdene, K.; Jin, L.; Lei, C.; et al. Feeding a High-Concentrate Corn Straw Diet Increased the Release of Endotoxin in the Rumen and pro-Inflammatory Cytokines in the Mammary Gland of Dairy Cows. BMC Vet. Res. 2014, 10, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abaker, J.A.; Xu, T.L.; Jin, D.; Chang, G.J.; Zhang, K.; Shen, X.Z. Lipopolysaccharide Derived from the Digestive Tract Provokes Oxidative Stress in the Liver of Dairy Cows Fed a High-Grain Diet. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 666–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zain, M.; Tanuwiria, U.H.; Syamsu, J.A.; Yunilas, Y.; Pazla, R.; Putri, E.M.; Makmur, M.; Amanah, U.; Shafura, P.O.; Bagaskara, B. Nutrient Digestibility, Characteristics of Rumen Fermentation, and Microbial Protein Synthesis from Pesisir Cattle Diet Containing Non-Fiber Carbohydrate to Rumen Degradable Protein Ratio and Sulfur Supplement. Vet. World 2024, 17, 672–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sammad, A.; Wang, Y.J.; Umer, S.; Lirong, H.; Khan, I.; Khan, A.; Ahmad, B.; Wang, Y. Nutritional Physiology and Biochemistry of Dairy Cattle under the Influence of Heat Stress: Consequences and Opportunities. Animals 2020, 10, 793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, F.N.; Basalan, M. Ruminal Fermentation. In Rumenology; Millen, D.D., De Beni Arrigoni, M., Lauritano Pacheco, R.D., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 63–102. ISBN 978-3-319-30531-8. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, E.T.; Guan, L.L.; Lee, S.J.; Lee, S.M.; Lee, S.S.; Lee, I.D.; Lee, S.K.; Lee, S.S. Effects of Flavonoid-Rich Plant Extracts on In Vitro Ruminal Methanogenesis, Microbial Populations and Fermentation Characteristics. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2015, 28, 530–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onu, E.; Ugwoke, J.; Edeh, H.; Onu, M.; Onyimonyi, A. A Review: Flavonoid; A Phyto-Nutrient and Its Impact in Livestock Animal Nutrition. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2024, 21, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Shi, H.T.; Wang, Y.C.; Li, S.L.; Cao, Z.J.; Yang, H.J.; Wang, Y.J. Carbohydrate and Amino Acid Metabolism and Oxidative Status in Holstein Heifers Precision-Fed Diets with Different Forage to Concentrate Ratios. Animal 2020, 14, 2315–2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Jin, L.; Chen, T. The Effects of Secretory IgA in the Mucosal Immune System. BioMed. Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 2032057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhtar, M.; Guo, S.; Guo, Y.; Zahoor, A.; Shaukat, A.; Chen, Y.; Umar, T.; Deng, P.G.; Guo, M. Upregulated-Gene Expression of pro-Inflammatory Cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6) via TLRs Following NF-κB and MAPKs in Bovine Mastitis. Acta Trop. 2020, 207, 105458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, M.; Lv, Z.; Huang, Y.; Cheng, Z.; Meng, Z.; Yang, T.; Yan, Q.; Lin, M.; Zhan, K.; Zhao, G. Quercetin Alleviates Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Inflammatory Response in Bovine Mammary Epithelial Cells by Suppressing TLR4/NF-κB Signaling Pathway. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 915726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.K.; Zhang, X.X.; Li, F.D.; Li, C.; Li, G.Z.; Zhang, D.Y.; Song, Q.Z.; Li, X.L.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, W.M. Characterization of the Rumen Microbiota and Its Relationship with Residual Feed Intake in Sheep. Animal 2021, 15, 100161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foksowicz-Flaczyk, J.; Wójtowski, J.A.; Danków, R.; Mikołajczak, P.; Pikul, J.; Gryszczyńska, A.; Łowicki, Z.; Zajączek, K.; Stanisławski, D. The Effect of Herbal Feed Additives in the Diet of Dairy Goats on Intestinal Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB) Count. Animals 2022, 12, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betancur-Murillo, C.L.; Aguilar-Marín, S.B.; Jovel, J. Prevotella: A Key Player in Ruminal Metabolism. Microorganisms 2022, 11, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Su, X.; Li, J.; Yang, Y.; Wang, P.; Yan, F.; Yao, J.; Wu, S. Real-Time Monitoring of Ruminal Microbiota Reveals Their Roles in Dairy Goats during Subacute Ruminal Acidosis. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2021, 7, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, J.; Liu, M.; Su, X.; Zhan, K.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, G. Effects of Alfalfa Flavonoids on the Production Performance, Immune System, and Ruminal Fermentation of Dairy Cows. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2017, 30, 1416–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grilli, D.J.; Fliegerová, K.; Kopečný, J.; Lama, S.P.; Egea, V.; Sohaefer, N.; Pereyra, C.; Ruiz, M.S.; Sosa, M.A.; Arenas, G.N.; et al. Analysis of the Rumen Bacterial Diversity of Goats during Shift from Forage to Concentrate Diet. Anaerobe 2016, 42, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kibegwa, F.M.; Bett, R.C.; Gachuiri, C.K.; Machuka, E.; Stomeo, F.; Mujibi, F.D. Diversity and Functional Analysis of Rumen and Fecal Microbial Communities Associated with Dietary Changes in Crossbreed Dairy Cattle. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0274371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yang, E.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, J.; Yuan, L.; Liu, R.; Ullah, S.; Wang, Q.; Mushtaq, N.; Shi, Y.; et al. Molecular Characterization of Gut Microbial Shift in SD Rats after Death for 30 Days. Arch. Microbiol. 2020, 202, 1763–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, G.; Cox, F.; Ganesh, S.; Jonker, A.; Young, W.; Janssen, P.H. Rumen Microbial Community Composition Varies with Diet and Host, but a Core Microbiome Is Found across a Wide Geographical Range. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 14567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Tong, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xiong, B.; Jiang, L. Metabolomics Reveals Potential Biomarkers in the Rumen Fluid of Dairy Cows with Different Levels of Milk Production. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2020, 33, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Sun, D.; Wang, X.; Mao, S. A Combined Metabolomic and Proteomic Study Revealed the Difference in Metabolite and Protein Expression Profiles in Ruminal Tissue From Goats Fed Hay or High-Grain Diets. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akram, W.; Tagde, P.; Ahmed, S.; Arora, S.; Emran, T.B.; Babalghith, A.O.; Sweilam, S.H.; Simal-Gandara, J. Guaiazulene and Related Compounds: A Review of Current Perspective on Biomedical Applications. Life Sci. 2023, 316, 121389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, S.; He, W.; Wu, G. Hydroxyproline in Animal Metabolism, Nutrition, and Cell Signaling. Amino Acids 2022, 54, 513–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orzuna-Orzuna, J.F.; Dorantes-Iturbide, G.; Lara-Bueno, A.; Chay-Canul, A.J.; Miranda-Romero, L.A.; Mendoza-Martínez, G.D. Meta-Analysis of Flavonoids Use into Beef and Dairy Cattle Diet: Performance, Antioxidant Status, Ruminal Fermentation, Meat Quality, and Milk Composition. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1134925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frutos, P.; Hervás, G.; Natalello, A.; Luciano, G.; Fondevila, M.; Priolo, A.; Toral, P.G. Ability of Tannins to Modulate Ruminal Lipid Metabolism and Milk and Meat Fatty Acid Profiles. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2020, 269, 114623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Sun, Z.; Tu, Y.; Si, B.; Liu, Y.; Yang, L.; Luo, H.; Yu, Z. Untargeted Metabolomic Investigate Milk and Ruminal Fluid of Holstein Cows Supplemented with Perilla Frutescens Leaf. Food Res. Int. 2021, 140, 110017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biernat, K.A.; Li, B.; Redinbo, M.R. Microbial Unmasking of Plant Glycosides. mBio 2018, 9, e02433-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Items | Treatment | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| L | H | D | |

| Diet composition (% DM) | |||

| Alfalfa hay | 24 | 16 | 15.84 |

| Corn silage | 24 | 11 | 10.89 |

| Ryegrass | 12 | 8 | 7.92 |

| Corn | 28 | 29.12 | 28.82 |

| Wheat bran | 0 | 17.87 | 17.69 |

| Calcium bicarbonate | 2.13 | 1.13 | 1.12 |

| Soybean meal | 5.73 | 7.88 | 7.81 |

| DDGS | 2.14 | 7 | 6.93 |

| Premix | 1 | 1 | 0.99 |

| Salt | 1 | 1 | 0.99 |

| Dandelion extract | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Forage to concentrate ratio | 60:40 | 35:65 | 35:65 |

| Nutrient profile | |||

| Crude ash (% of DM) | 11.23 | 12.01 | 11.42 |

| Crude protein (% of DM) | 15.06 | 16.41 | 16.22 |

| Crude fat (% of DM) | 1.40 | 2.20 | 1.82 |

| Neutral detergent fiber (% of DM) | 39.32 | 37.61 | 37.73 |

| Acid detergent fiber (% of DM) | 22.55 | 18.52 | 18.56 |

| Metabolizable Energy (MJ/Kg) | 14.84 | 15.21 | 15.05 |

| Calcium (% of DM) | 1.04 | 1.02 | 1.02 |

| Phosphorous (% of DM) | 0.33 | 0.39 | 0.37 |

| Flavonoid Target Metabolites | Concentrations (μg/g) |

|---|---|

| Isorhamnetin | 2021.81 |

| Luteolin | 1711.59 |

| Puerarin | 1112.88 |

| Cynaroside | 508.10 |

| Genkwanin | 352.48 |

| Quercimeritrin | 255.89 |

| Hyperoside | 232.40 |

| Chrysin | 206.49 |

| Daidzin | 177.18 |

| 3′-Methoxypuerarin | 163.30 |

| Scutellarein | 83.63 |

| Scutellarin | 81.63 |

| Apigenin | 70.63 |

| Linarin | 66.79 |

| Daidzein | 61.21 |

| Phlorizin | 58.43 |

| Rutin | 42.53 |

| Glycitin | 39.58 |

| Genistin | 33.43 |

| Quercitrin | 33.12 |

| Target Gene | Primer Sequence (5′–3′) | Product Length (bp) | Reference/Gene Bank Accession No. |

|---|---|---|---|

| NF-κB | F: CTCACCAATGGCCTCCTCTC | 179 | XM_018043384.1 |

| R: ACACCCTCCCAGAATCCGTA | |||

| TLR4 | F: TTCGCATCTGGATAAATCCAGC | 207 | NM_001285574.1 |

| R: CTGAGAACCGAGAGCTGGGAC | |||

| TNF-α | F: CAAGTAACAAGCCGGTAGCC | 153 | XM_005696606.3 |

| R: AGATGAGGTAAAGCCCGTCA | |||

| IL-1β | F: CATGTGTGCTGAAGGCTCTC | 172 | XM_013967700.2 |

| R: AGTGTCGGCGTATCACCTTT | |||

| IL-6 | F: CCAATCTGGGTTCAATCAGG | 240 | NM_001285640.1 |

| R: ACCCACTCGTTTGAGGACTG | |||

| IL-8 | F: ATGGAACAATGTACATGTGACAC | 367 | XM_005681749.3 |

| R: CTGAGAGTTATTGAGAGTGGGC | |||

| IL-10 | F: TTAAGGGTTACCTGGGTTGC | 237 | XM_005690416.3 |

| R: CCCTCTCTTGGAGCATATTGA | |||

| GAPDH | F: CGGCACAGTCAAGGCAGAGAAC | 115 | XM_005680968.3 |

| R: CACGTACTCAGCACCAGCATCAC |

| Items | Treatment | SEM | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L | H | D | |||

| Milk fat (%) W1 | 2.58 | 2.22 | 2.44 | 0.285 | 0.706 |

| Milk fat (%) W2 | 2.42 | 2.29 | 2.36 | 0.226 | 0.930 |

| Milk fat (%) W3 | 2.31 | 2.07 | 2.35 | 0.142 | 0.391 |

| Milk fat (%) W4 | 2.34 | 2.18 | 2.41 | 0.149 | 0.594 |

| Milk fat (%) W5 | 2.73 | 2.04 | 2.36 | 0.205 | 0.115 |

| Non-Fat Solid (%) W1 | 7.78 | 8.21 | 8.10 | 0.200 | 0.337 |

| Non-Fat Solid (%) W2 | 7.83 | 7.94 | 7.92 | 0.106 | 0.767 |

| Non-Fat Solid (%) W3 | 7.63 | 7.88 | 7.80 | 0.184 | 0.625 |

| Non-Fat Solid (%) W4 | 7.60 | 7.88 | 7.84 | 0.163 | 0.442 |

| Non-Fat Solid (%) W5 | 7.64 | 7.82 | 7.74 | 0.147 | 0.719 |

| Lactose (%) W1 | 3.49 | 3.68 | 3.63 | 0.090 | 0.349 |

| Lactose (%) W2 | 3.51 | 3.55 | 3.56 | 0.049 | 0.742 |

| Lactose (%) W3 | 3.42 | 3.53 | 3.50 | 0.082 | 0.647 |

| Lactose (%) W4 | 3.41 | 3.52 | 3.53 | 0.073 | 0.460 |

| Lactose (%) W5 | 3.43 | 3.47 | 3.51 | 0.066 | 0.748 |

| Protein (%) W1 | 3.68 | 3.85 | 3.84 | 0.087 | 0.356 |

| Protein (%) W2 | 3.76 | 3.75 | 3.71 | 0.051 | 0.751 |

| Protein (%) W3 | 3.61 | 3.68 | 3.73 | 0.074 | 0.574 |

| Protein (%) W4 | 3.60 | 3.71 | 3.73 | 0.077 | 0.447 |

| Protein (%) W5 | 3.60 | 3.71 | 3.73 | 0.069 | 0.703 |

| Items | Treatment | SEM | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L | H | D | |||

| Acetate (mmol/L) | 72.35 a | 32.76 b | 58.87 a | 7.12 | 0.013 |

| Propionate (mmol/L) | 31.51 B | 115.54 A | 82.25 A | 11.63 | 0.001 |

| Butyrate (mmol/L) | 28.32 | 51.36 | 34.34 | 7.96 | 0.142 |

| Valerate (mmol/L) | 0.44 b | 3.97 a | 1.74 ab | 0.87 | 0.044 |

| Total VFA (mmol/L) | 131.85 b | 204.64 a | 188.28 a | 15.89 | 0.014 |

| Items | Treatment | SEM | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L | H | D | |||

| Phyla (%) | |||||

| Bacteroidota | 49.483 | 45.422 | 44.561 | 4.861 | 0.761 |

| Firmicutes | 41.629 | 48.831 | 44.288 | 5.202 | 0.627 |

| Proteobacteria | 2.108 b | 1.890 b | 6.875 a | 1.259 | 0.032 |

| Spirochaetota | 1.016 | 1.398 | 1.793 | 0.848 | 0.829 |

| Actinobacteriota | 1.530 | 0.661 | 0.207 | 0.496 | 0.415 |

| Patescibacteria | 0.381 | 0.771 | 0.736 | 0.226 | 0.474 |

| Synergistota | 1.371 | 0.004 | 0.105 | 3.080 | 0.381 |

| Cyanobacteria | 0.795 | 0.267 | 0.341 | 0.347 | 0.657 |

| Desulfobacterota | 0.546 | 0.304 | 0.311 | 0.120 | 0.423 |

| Fibrobacterota | 0.185 | 0.140 | 0.297 | 0.093 | 0.495 |

| Genera (%) | |||||

| Prevotella | 22.077 a | 8.508 b | 21.535 a | 2.658 | 0.010 |

| uncultured_rumen_bacterium | 6.180 | 12.487 | 7.080 | 2.141 | 0.127 |

| unclassified_Prevotellaceae | 7.709 | 11.682 | 5.013 | 2.192 | 0.181 |

| Prevotellaceae_UCG_001 | 2.766 | 5.693 | 4.040 | 1.291 | 0.328 |

| Rikenellaceae_RC9_gut_group | 3.394 | 2.293 | 3.184 | 1.011 | 0.481 |

| Prevotellaceae_UCG_003 | 1.604 | 1.588 | 0.870 | 0.606 | 0.677 |

| Prevotellaceae_YAB2003_group | 2.715 | 0.782 | 0.179 | 1.009 | 0.450 |

| unclassified_Muribaculaceae | 0.535 | 1.185 | 1.655 | 0.697 | 0.580 |

| Succiniclasticum | 2.646 | 7.355 | 6.319 | 1.874 | 0.304 |

| unclassified_Clostridia_UCG_014 | 1.838 | 6.396 | 4.770 | 2.857 | 0.629 |

| Ruminococcus | 1.959 b | 6.927 a | 3.500 ab | 1.352 | 0.085 |

| Selenomonas | 4.443 | 0.838 | 1.760 | 1.111 | 0.171 |

| unclassified_Selenomonadaceae | 2.670 | 2.633 | 1.397 | 1.316 | 0.756 |

| NK4A214_group | 1.823 | 2.247 | 2.122 | 0.623 | 0.886 |

| unclassified_Lachnospiraceae | 4.255 | 0.736 | 0.611 | 1.073 | 0.233 |

| Agathobacter | 0.513 | 1.876 | 1.981 | 0.875 | 0.492 |

| Lachnospira | 1.681 | 0.865 | 1.528 | 0.719 | 0.760 |

| Christensenellaceae_R_7_group | 1.127 | 1.996 | 0.747 | 0.510 | 0.350 |

| Succinivibrio | 0.365 | 0.932 | 3.399 | 0.903 | 0.176 |

| Treponema | 1.000 | 1.387 | 1.773 | 0.848 | 0.830 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mgeni, M.S.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Y.; Dong, X.; Xiu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Chen, J.; Sun, Y. Effects of Dandelion Extracts on the Ruminal Microbiota, Metabolome, and Systemic Inflammation in Dairy Goats Fed a High-Concentrate Diet. Vet. Sci. 2026, 13, 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci13010028

Mgeni MS, Zhang L, Chen Y, Dong X, Xiu Z, Zhang J, Chen J, Sun Y. Effects of Dandelion Extracts on the Ruminal Microbiota, Metabolome, and Systemic Inflammation in Dairy Goats Fed a High-Concentrate Diet. Veterinary Sciences. 2026; 13(1):28. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci13010028

Chicago/Turabian StyleMgeni, Mussa Suleiman, Li Zhang, Yu Chen, Xianwen Dong, Ziqing Xiu, Junqiu Zhang, Juncai Chen, and Yawang Sun. 2026. "Effects of Dandelion Extracts on the Ruminal Microbiota, Metabolome, and Systemic Inflammation in Dairy Goats Fed a High-Concentrate Diet" Veterinary Sciences 13, no. 1: 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci13010028

APA StyleMgeni, M. S., Zhang, L., Chen, Y., Dong, X., Xiu, Z., Zhang, J., Chen, J., & Sun, Y. (2026). Effects of Dandelion Extracts on the Ruminal Microbiota, Metabolome, and Systemic Inflammation in Dairy Goats Fed a High-Concentrate Diet. Veterinary Sciences, 13(1), 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci13010028