Morbidity and Mortality of Eastern Barn Owls (Tyto javanica) Admitted to a Southeast Queensland Wildlife Hospital

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Aims

2.2. Methods

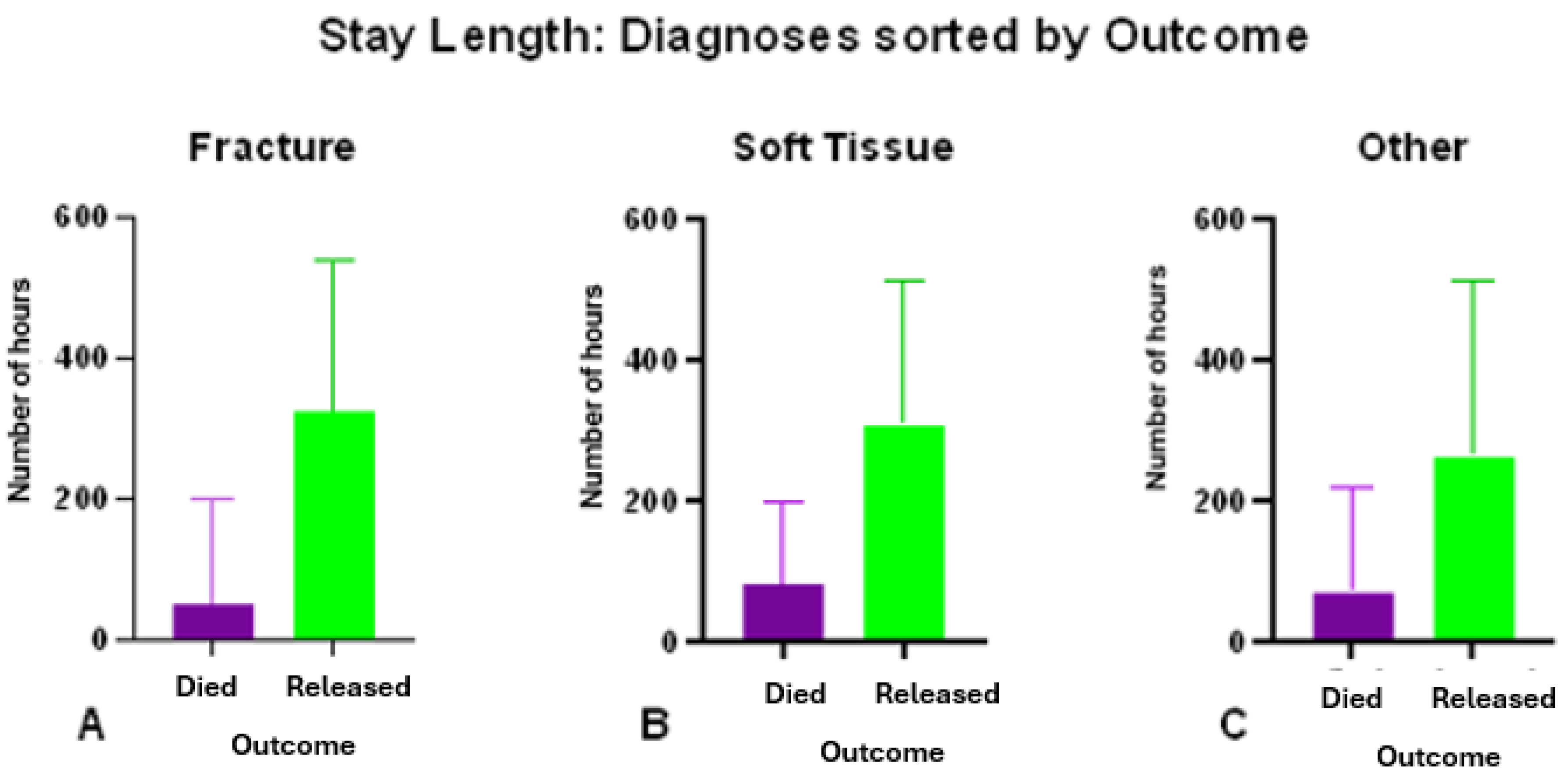

- The extracted patient information included (where known) sex; age; date of admission; reason for admission; diagnosis; hospital stay length; and outcome (died [euthanized, spontaneous death, unexpected death], discharged [discharged to wildlife carers, discharged into wild from the hospital], or in hospital [receiving treatment or in rehabilitation at the time data were collected]).

- The reason for admission was categorized to allow comparisons between admission variables: ground find; animal attack; motor vehicle; environmental; referral by a wildlife carer or other veterinarian; and unknown.

- The breeding season was defined as winter (July to September) and spring (October to December). The non-breeding season was defined as summer (January to March) and autumn (April to June).

- Age was classified as either adult or subadult.

Study Limitations

- The data may have been incomplete due to a lack of standardized recording by different hospital staff.

- The small sample sizes of some categories required further collapse of categories to obtain meaningful interpretations.

- The data had low specificity for the cause of injuries and separated diagnoses in a way that may have attributed injuries from the same source into several categories. For example, motor vehicle injuries can result in soft tissue trauma; some environmental interactions such as window impact can result in bone fractures.

- The difficulties of identifying age and sex in this species, especially in a hospital setting, meant that the ages and sexes of many of the owls were not accurately determined at the time of examination. Records of sex identification were incomplete to the extent that we excluded them from the study.

- As the data were derived from a single wildlife hospital, they may not be a true measure of population dynamics.

3. Results

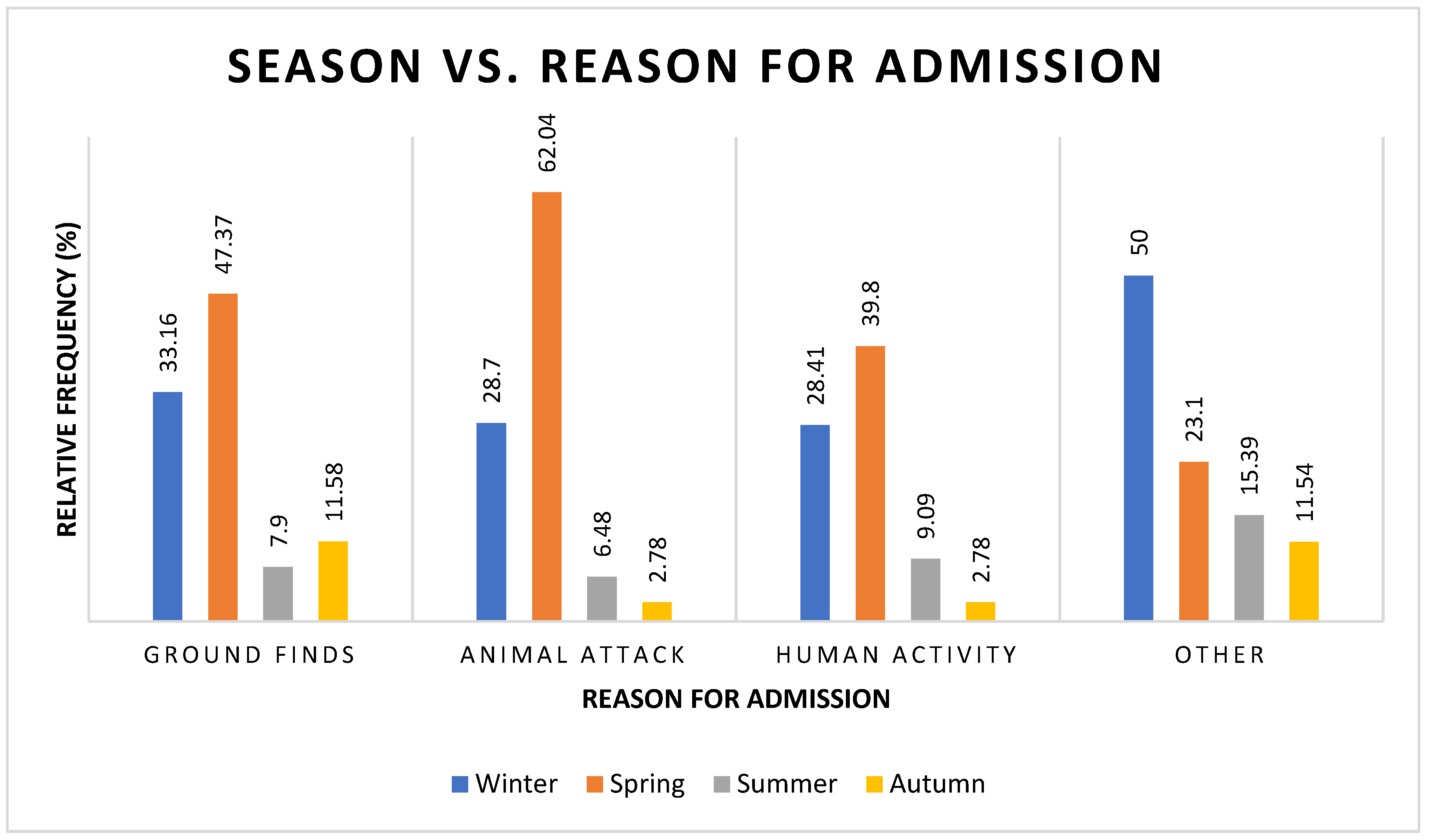

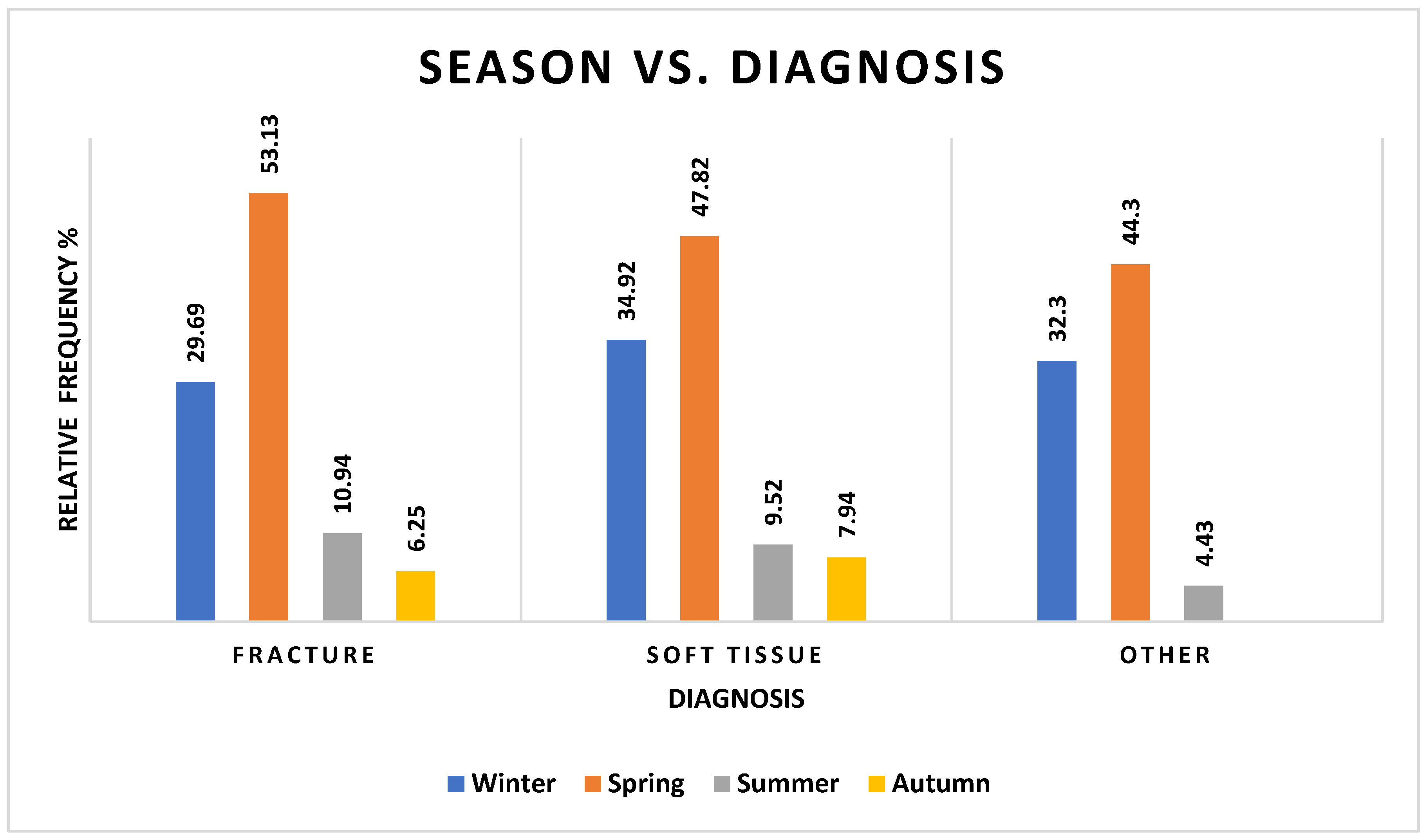

3.1. Seasonality

3.2. Age

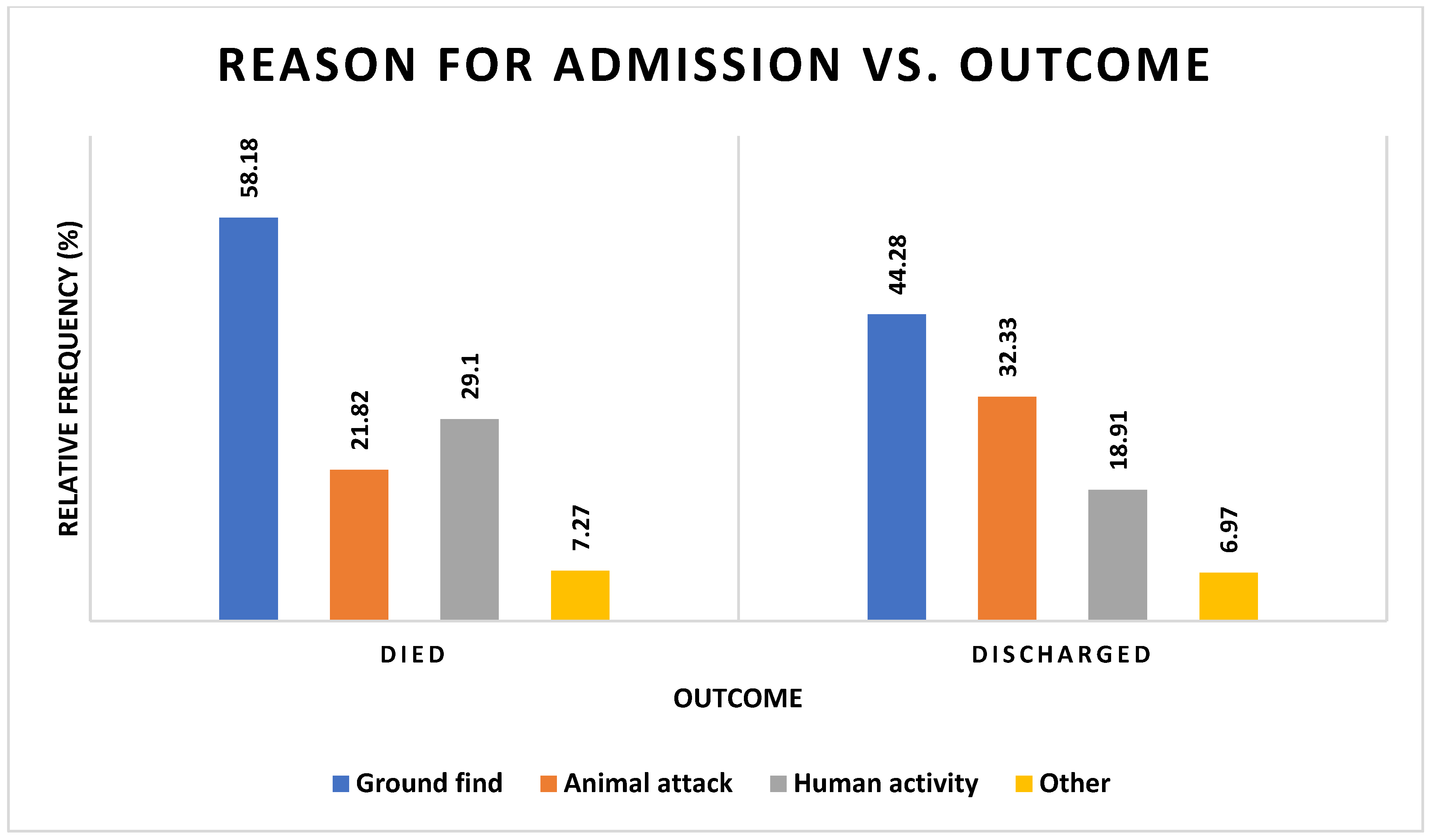

3.3. Reason for Admission

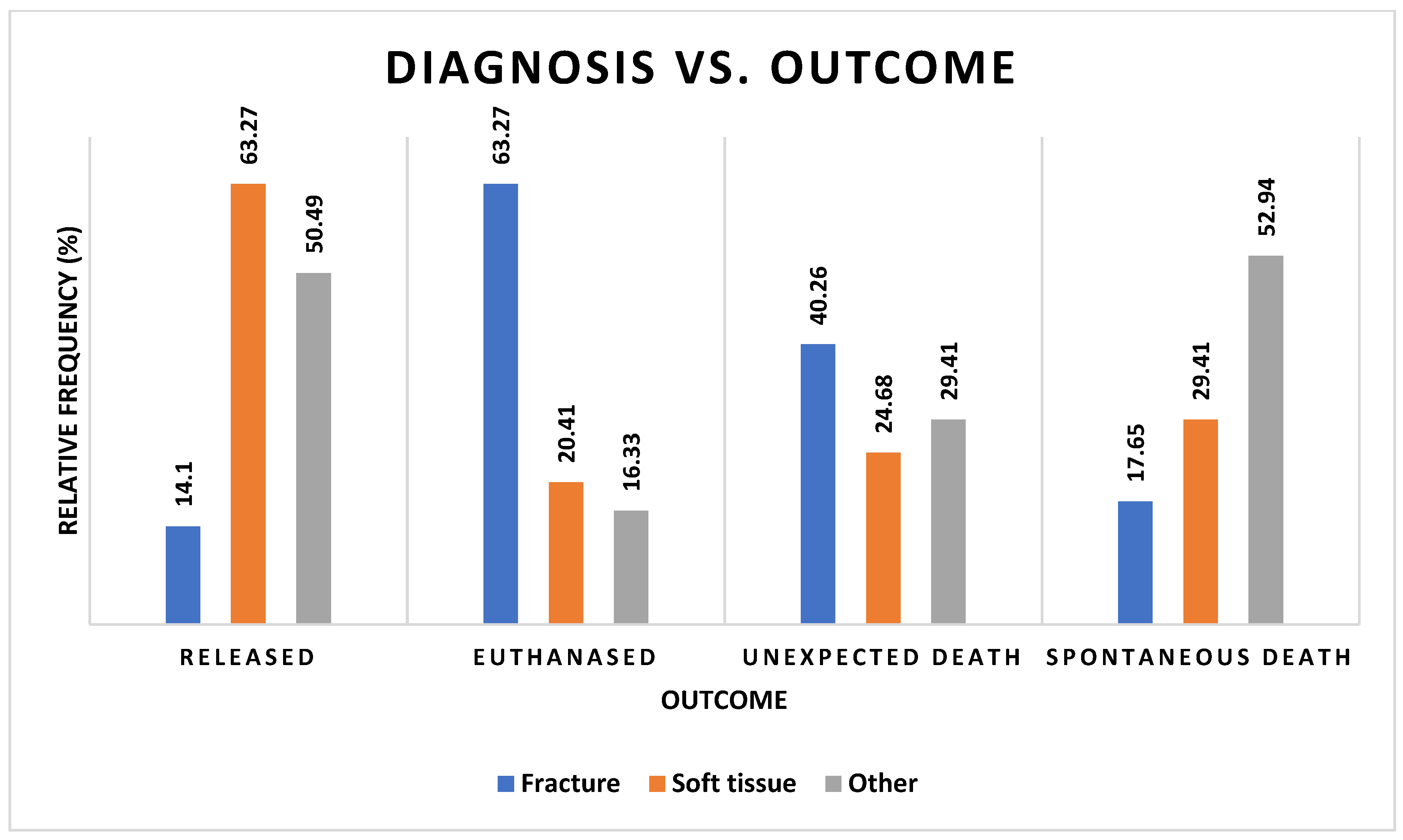

3.4. Diagnosis

3.5. Outcome

4. Discussion

Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shawyer, C. The Barn Owl (Hamlyn Species Guides); Hamlyn: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, I. Predator-Prey Relationships and Conservation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bunn, D.; Warburton, A.B.; Wilson, R.D.S. The Barn Owl. Ornithol. Adv. 1982, 100, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Fulton, G.; Fulton, G.; Cheung, Y.W. A comparison of urban and peri-urban/hinterland nocturnal birds at Brisbane, Australia. Pac. Conserv. Biol. 2020, 26, 238–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, I. Barn Owls: Predator-Prey Relationships and Conservation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kadlecova, G.; Voslarova, E.; Vecerek, V. Diurnal raptors at rescue centres in the Czech Republic: Reasons for admission, outcomes, and length of stay. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0279501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyle, M. Contrasting effects of climate on grey heron, mallee fowl and barn owl populations. Wildl. Res. 2011, 39, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.; Wilson, M.P.; Durkin, J.W. Breeding biology of the Barn Owl Tyto alba in central Mali. Int. J. Avian Sci. 1986, 128, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hindmarch, S.; Elliott, J.; McCann, S.; Levesque, P. Habitat use by barn owls across a rural to urban gradient and an assessment of stressors including, habitat loss, rodenticide exposure and road mortality. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 164, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McOrist, S. Deaths in free-living Barn owls (Tyto alba). Avian Pathol. 1989, 18, 745–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, A.; Wyllie, I.; Asher, A. Mortality causes in British Barn Owls Tyto alba, with a discussion of aldrin-dieldrin poisoning. Ibis 1991, 133, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, A.; Wyllie, N.; Dale, L. Biology and Conservation of Owls of the Northern Hemisphere: 2nd International Symposium; Duncan, J.R., Johnson, D.H., Nicholls, T.H., Eds.; General Technical Report NC-190. St. Paul, MN, USA; U.S. Departmant of Agriculture, Forest Service, North Central Forest Experiment Station: Madison, WI, USA, 1997; pp. 299–307.

- Westaway, D.; Burnett, S.; Shimizu-Kimura, Y.; Srivastava, S. The distribution of forest dwelling Tyto owls in south-east Queensland: Environmental drivers and conservation status. Austral Ornithol. 2024, 19, 56. [Google Scholar]

- Couper, D.; Bexton, S. Veterinary care of wild owl casualties. In Pract. 2012, 34, 270–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtney, J.; Deebus, S.J.S. Observations on the Post-fledging Period of the Barn Owl Tyto alba. Aust. Field Ornithol. 2006, 23, 159–162. [Google Scholar]

- Roulin, A.; Ducrest, A.; Dijkstra, C. Effect of brood size manipulations on parents and offspring in the Barn Owl Tyro alba. Ardea 1999, 87, 91–100. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke, R.; Grant, H.; Ebsworth, I.; Rendall, A.R.; Isaac, B.; White, J.G. Can owls be used to monitor the impacts of urbanisation? A cautionary tale of variable detection. Wildl. Res. 2017, 44, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, M. Occurrence of the Eastern Barn Owl ’Tyto alba delicatula’ in the Centennial Parklands, Sydney. Aust. Field Ornithol. 2019, 36, 56–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, J.R.; Rees, G.L.; Kingsford, R.T.; Letnic, M. Indirect commensalism between an introduced apex predator and a native avian predator. Biodivers. Conserv. 2019, 28, 2687–2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.L.; Gonzalez Villavincencio, C.M.; Wilson, S. Chronic ocular lesions in tawny owls (Strix aluco) injured by road traffic. Vet. Rec. 2006, 159, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Doneley, R.; Hicks, A.; Hill, A. Morbidity and Mortality of Eastern Barn Owls (Tyto javanica) Admitted to a Southeast Queensland Wildlife Hospital. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 284. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci12030284

Doneley R, Hicks A, Hill A. Morbidity and Mortality of Eastern Barn Owls (Tyto javanica) Admitted to a Southeast Queensland Wildlife Hospital. Veterinary Sciences. 2025; 12(3):284. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci12030284

Chicago/Turabian StyleDoneley, Robert, Ashleigh Hicks, and Andrew Hill. 2025. "Morbidity and Mortality of Eastern Barn Owls (Tyto javanica) Admitted to a Southeast Queensland Wildlife Hospital" Veterinary Sciences 12, no. 3: 284. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci12030284

APA StyleDoneley, R., Hicks, A., & Hill, A. (2025). Morbidity and Mortality of Eastern Barn Owls (Tyto javanica) Admitted to a Southeast Queensland Wildlife Hospital. Veterinary Sciences, 12(3), 284. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci12030284