Simple Summary

Bovine Respiratory Disease (BRD) remains a major cattle health challenge, driven by viral, bacterial, and environmental factors. Integrated approaches using RNA-Seq and non-coding RNA profiling have revealed key host immune responses, while bacterial and viral metagenomics enable unbiased detection of known and emerging pathogens. Complementary respiratory microbiome studies highlight microbial dynamics influencing disease susceptibility and progression. Emerging technologies, including Oxford Nanopore sequencing, allow rapid species-level identification and real-time diagnostics. Combining host transcriptomics, viral metagenomics, and microbiome analyses provides a comprehensive understanding of BRD pathogenesis, supporting improved interventions, vaccines, and evidence-based disease management strategies in cattle.

Abstract

Bovine respiratory disease (BRD) is a multifactorial syndrome and a leading cause of morbidity and economic loss in global cattle production. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) platforms, including Illumina and Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT), have enabled high-resolution profiling of the bovine respiratory microbiome and virome, revealing novel viral contributors such as bovine rhinitis A virus (BRAV) and influenza D virus (IDV). Transcriptomic approaches, including RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) and microRNA (miRNA) profiling, provide insights into host immune responses and identify potential biomarkers for disease prediction. Traditional diagnostic methods—culture, ELISA, and immunohistochemistry—are increasingly complemented by PCR-based and metagenomic techniques, improving sensitivity and specificity. Despite technological progress, gaps remain in virome characterization, miRNA function, and the integration of multi-omics data. Standardized protocols and longitudinal studies are needed to validate microbial signatures and support field-deployable diagnostics. Advances in bioinformatics, particularly network-based integrative pipelines, are becoming essential for harmonizing multi-omics datasets and revealing complex host–pathogen interactions. The objective of this comprehensive review was to synthesize current understanding of the bovine transcriptomic response to BRD as well as the respiratory microbiome and virome, emphasizing how advanced sequencing technologies have transformed microbial profiling and molecular diagnostics in BRD.

1. Introduction

Bovine respiratory disease (BRD) is a complex, multifactorial syndrome and remains the leading cause of respiratory illness and mortality in cattle worldwide. It imposes significant economic burdens due to reduced productivity, increased veterinary costs, and animal losses [1,2,3]. The complex nature of BRD and the involvement of multiple pathogens and disease-causing factors can often complicate disease diagnosis. Traditionally, BRD diagnosis has been and remains centered on the observation of clinical signs of infection, as well as imaging techniques for the detection of lung lesions and certain behavioral parameters relating to infection [3]. Although a central part of BRD diagnostics, these methods can lack sensitivity in the case of subclinical disease and specificity regarding the pathogen causing the initial infection. In addition to these clinical-based approaches, lab-based approaches, such as pathogen culture, immunohistochemistry and enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) have been widely adopted and have shown success in the diagnosis of BRD. However, these approaches are limited in their capabilities to identify novel pathogens and sensitivity. Furthermore, some BRD pathogens can be difficult to culture which can also lead to bias in results. The advancement in molecular methods such as PCR allowed for more advanced BRD diagnostics, with many studies employing this approach for the detection of BRD-associated pathogens [4,5]. However, PCR-based techniques often fall short in detecting unknown species.

Advances in molecular diagnostics have begun to address these limitations. Next-generation sequencing approaches have been widely used to study BRD pathogenesis and the immune response of cattle to both naturally acquired [6,7,8] and experimentally induced BRD [9,10,11]. These studies were able to identify genes differentially expressed across a range of different tissue types in response to BRD infection, as well as their associated biological pathways. These differentially expressed genes (DEGs) with could offer potential as biomarkers in future BRD screening approaches. In addition to host immunity, NGS approaches have also been used to investigate the respiratory microbiome during BRD infection. Central to BRD pathogenesis is the bovine respiratory microbiome—a diverse community of bacteria that supports mucosal homeostasis and modulates immune responses, is central to BRD pathogenesis. When this microbial balance is disrupted, a condition known as dysbiosis, cattle become more susceptible to colonization by pathogenic organisms and subsequent disease progression. The interplay between microbial communities, host immunity, and environmental stressors underpins the complexity of BRD [12,13]. For example, a study utilized NGS technologies to analyze lung and mediastinal lymph node microbiomes in both healthy and BRD-affected cattle, revealing significantly higher bacterial loads in diseased lungs [14] (Johnston et al. (2017)). Notably, they identified Sneathia amnii strain SN35—a previously unassociated member of the Leptotrichiaceae family—highlighting the potential of sequencing to uncover novel etiological agents [14].

In addition to bacterial communities, the bovine respiratory virome plays a critical yet underexplored role in BRD. This virome includes both pathogenic and commensal viruses that influence host–pathogen interactions and immune modulation. Virome composition is dynamic and influenced by factors such as stress, immune status, co-infections, and geographic location [13,15,16,17]. Metagenomic studies have expanded the known viral repertoire associated with BRD, showing that affected cattle often harbor viruses beyond classical pathogens such as BoHV-1, BPI-3, and BRSV. Emerging viruses like bovine rhinitis A virus (BRAV) and influenza D virus (IDV) have also been implicated [18]. Recent advances in high-throughput sequencing, particularly portable platforms like ONT MinION, have enabled rapid detection and genomic characterization of both established and emerging viruses, including BoCV, BRBV, BoNV, and UTPV1 [19,20,21].

Integrating metagenomic and viromic data through second- and third-generation sequencing technologies offers high-resolution insights into microbial interactions and their contributions to BRD pathophysiology. These approaches facilitate the detection of novel pathogens, quantification of microbial load, and identification of microbial signatures predictive of disease states. Moreover, portable sequencing devices like the MinION support point-of-care diagnostics and real-time surveillance, enhancing both research and field-based disease management. This comprehensive review synthesizes current understanding of the bovine transcriptomic response to BRD as well as the respiratory microbiome and virome, emphasizing how advanced sequencing technologies have transformed microbial profiling and molecular diagnostics in BRD. These innovations hold promise for improving disease detection, guiding vaccine development, and refining therapeutic strategies.

2. Materials and Methods

To provide a comprehensive overview of research progression in BRD, a structured literature search was conducted across PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and ScienceDirect, with supplementary searches in Google Scholar. No restrictions were placed on publication date; all relevant studies available up to October 2025 were considered to ensure comprehensive coverage of the topic. The search strategy employed Boolean operators (AND, OR) and was adapted to each database’s syntax. Keywords were grouped into six thematic domains to ensure broad coverage: BRD pathogenesis and host–pathogen interactions; Respiratory microbiome and virome; Diagnostic methodologies (including traditional and molecular approaches); Sequencing technologies (e.g., Illumina, Oxford Nanopore, NGS, metagenomics); Host defense mechanisms (URT/LRT, mucociliary clearance, innate immunity); Microbiome development and influencing factors (e.g., diet, stress, antimicrobials, vaccination).

Diagnostics were included as a core theme to reflect their central role in shaping BRD research—from early pathogen identification to the emergence of multi-omics approaches. The inclusion of both traditional and molecular diagnostics was intentional, as it illustrates the evolution of tools that underpin current understanding and surveillance strategies. Extracted studies were synthesized narratively and organized thematically. This approach enabled the identification of cross-cutting trends, methodological variability, and emerging knowledge gaps across BRD research domains. A total of 90 studies were included following the application of relevant filters.

3. Laboratory and Molecular Diagnostics for BRD

Diagnostic innovation is a central theme in the progression of BRD research, reflecting a shift from traditional pathogen detection methods to high-resolution, multi-omics approaches. Traditional diagnostics such as culture, ELISA, and immunohistochemistry (IHC) remain foundational in the diagnosis of BRD [22,23,24,25]. However, these approaches can be limited by factors such as low sensitivity, an inability to detect novel or unculturable pathogens, and a reliance on postmortem sampling [24,25,26].

3.1. Application of PCR Methodologies in the Diagnosis of BRD

Advances in molecular and proteomic technologies, such as multiplex real-time PCR and mass spectrometry, have enabled rapid, sensitive, and high-throughput detection and identification of BRD pathogens, surpassing traditional culture methods [27]. These innovations also allow for detailed sub-species typing, improving differentiation between pathogenic and commensal bacterial genotypes. PCR-based testing is used widely in veterinary diagnostics, and multiplex PCR assays now enable simultaneous detection of multiple pathogens, including mixed infections, with improved speed and specificity [4,5,28]. As multiple pathogens are often responsible for BRD onset this approach could be preferred over the more conventional PCR methodologies. Furthermore, the multiplexing of multiple targets saves on time and cost associated with the reaction. Multiplex qPCR approaches have been used to detect both bacterial and viral pathogens commonly associated with BRD [4,5,28,29,30,31]. This approach offers a useful tool for the rapid simultaneous detection of BRD pathogens.

Another PCR-based approach involves the use of loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) assays, which allow for the rapid amplification of pathogen-specific DNA under constant temperature conditions. LAMP assays offer rapid, field-deployable solutions for detecting key bacterial agents without the need for thermal cycling equipment [32,33,34]. These assays have been adapted for the detection of key BRD-associated bacteria, including Mannheimia haemolytica, Pasteurella multocida, and Histophilus somni, directly from nasal swab samples [32]. Although PCR-based methodologies have aided BRD diagnostics, a main disadvantage of PCR methodologies is the need for prior knowledge of the viral and bacterial genome sequences, which can lead to PCR bias in the results [35,36,37]. Furthermore, this targeted approach also means that unknown pathogens cannot be identified [38]. Other approaches, such as next generation sequencing (NGS) technologies do not require predesigned probes and so offer increased discovery power for unknown or novel genes/transcripts [34,35,36,37].

3.2. NGS Technologies for BRD Diagnosis

NGS refers to the extensive list of DNA sequencing technologies and applications that have revolutionized genomic-based research [39]. These platforms allow for unbiased profiling of host transcriptomes, bacterial microbiomes, and viral communities, enabling the discovery of novel pathogens and biomarkers [6,10,14,18]. A comparison of the laboratory and molecular tools available to support BRD diagnosis along with their strengths and limitations is detailed Table 1. Collectively, these innovations not only enhance diagnostic sensitivity and specificity but also support systems-level understanding of BRD pathogenesis. They enable the integration of host–pathogen–microbiome data, facilitate biomarker discovery, and inform targeted interventions and vaccine development.

Table 1.

BRD Diagnostics: A comparative overview.

4. Host Transcriptomics in BRD

RNA-Seq has become a popular choice in research and has the potential to identify biomarkers associated with human diseases, with the aim to improve disease diagnosis [40,41,42]. The same can be seen in the context of animal health with this approach used to examine the difference in gene expression in BRD versus healthy animals, in both naturally acquired disease as well as in response to experimental challenges with BRD-associated pathogens. An overview of studies that utilised this approach in the study of BRD are given in Table 2.

Table 2.

RNA-Seq-based studies examining the molecular immune response to BRD.

In addition to the study of mRNA, RNA-Seq can be used to examine non-coding RNAs. miRNAs are small (21–23 nucleotide) non-coding RNAs, that play a crucial role in the regulation of gene expression in plants and animals [49]. The comparison of miRNA profiles between different states (e.g., diseased versus healthy), allows expression patterns or specific miRNAs implicated in various biological processes or disease pathogenesis to be identified [50]. In humans, miRNAs have shown to have an association with a range of diseases [51], with studies suggesting miRNA-expression profiles have potential as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers [52]. Similar has been shown in livestock [53], and it has been proposed that miRNAs play vital roles in the regulation of bovine immunity [54]. The association between miRNAs and antibody response of beef cattle to Mycoplasma bovis (M. bovis) was examined and four miRNAs showed a significant association to ELISA status, with these mainly involved in the host defence response to bacteria [55]. The miRNA expression profiles of bronchial lymph node tissue of dairy cattle following an experimental challenge with BRSV were examined, with 119 DE miRNAs identified in response to the viral challenge and genes targeted by these miRNAs were associated with pathogen recognition and interferon signalling [56]. Similar was conducted in beef cattle following experimental challenge with M. bovis or M. bovis and BVDV, whereby miRNA expression profiles of serum, white blood cells, liver, lymph nodes (mesenteric and trans-bronchial), spleen and thymus were examined [55]. Findings showed that certain miRNAs were higher in specific tissues compared to others and that differences in miRNA profiles were evident based on pathogen challenge [55]. Other studies conducted in vitro have examined the effect of BoHV-1 infection on miRNA expression with findings showing specific miRNAs to be involved in the suppression of BoHV-1 infection in MDBK cells [57].

Transcriptomic studies have significantly advanced our understanding of the bovine immune response to BRD, revealing consistent upregulation of genes involved in interferon signaling, pathogen recognition, and innate immunity across both natural and experimental infections. While whole blood transcriptomics offers a minimally invasive route for biomarker discovery, tissue-specific analyses, particularly of lymph nodes and lung, have uncovered localized gene expression patterns that may be critical for understanding pathogen tropism and disease progression. Notably, studies using experimental challenges with BoHV-1 and BRSV have provided clearer insights into host–pathogen interactions than those relying on naturally acquired BRD, where the initiating pathogen is often unknown. However, conflicting results in DEG profiles across studies suggest variability due to breed, sampling timepoints, and pathogen combinations. A major gap remains in the integration of transcriptomic data with other omics layers, such as miRNA and microbiome profiles, which could provide a more holistic view of BRD pathogenesis. Future research should prioritize longitudinal designs and multi-omics integration to identify robust biomarkers and therapeutic targets.

5. Characterization of the Bovine Respiratory Microbiome in BRD Infections

The term microbiome refers to the community of commensal, symbiotic and pathogenic microorganisms living within a particular environment [58]. In addition to the host’s structural and molecular defences, the microbiome of the bovine respiratory tract plays a key role in bovine health and disease [59]. The microbiome influences mucosal immunity, pathogen colonization resistance, and inflammatory responses. Disruptions in microbial balance—known as dysbiosis—can predispose cattle to infection by opportunistic pathogens and exacerbate disease progression. By characterizing microbial communities and their dynamics, researchers can identify microbial signatures associated with disease susceptibility, resilience, and progression. This knowledge supports the development of more integrated and predictive diagnostic tools, enabling earlier detection and targeted interventions for BRD.

5.1. Advances in BRD Diagnostics: Insights from 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing

NGS technologies have enabled the investigation of microbiomes in both humans and animals, with many studies utilising 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene sequencing to characterise bacterial microbiota [60]. Amplicon sequencing can be applied to almost all sample types [61], and to date has been used to study the microbiomes across a range of complex environments, with this approach able to identify both known and novel species. 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing uses a set of primers which, through PCR, bind to the conserved regions of the 16S rRNA gene [62]. A key benefit of this methodology is that it can be applied to samples of low biomass or those contaminated with host DNA [61].

In cattle, this approach has been used to identify BRD associated pathogens across the upper (URT) and lower (LRT) bovine respiratory tracts. An overview of the studies employing 16s rRNA sequencing in the study of BRD is provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

An overview of studies investigating the bovine respiratory microbiome during BRD infection using a 16S rRNA sequencing approach is presented. For each study, the anatomical sampling site, study population, geographical location, and a summary of the key findings are provided. The table is organized into three sections: URT, LRT, and combined URT–LRT studies.

5.2. Third-Generation Sequencing Techniques in BRD Microbiome Characterisation

Genomes are complex and can have many long repeating elements and structural variations that are so long, short-read paired-end applications are sometimes unable to resolve [75,76]. To overcome this, long-read sequencing offering reads more than several kilobases, can span these complex regions with a single continuous read, eliminating ambiguity in the position or size of genomic elements [75]. Furthermore, third generation approaches offer simplified library preparation as well as the generation of real-time results [75]. Long-read sequencing (often dubbed third-generation sequencing) is available across a range of sequencing platforms. Today, one of the most widely adopted tools of the third-generation technologies is the MinION from ONT. As Nanopore sequencing does not require imaging equipment to detect nucleotides, it has allowed the system to be scaled down in size to a smaller, portable device, with the cost of these devices often far less compared to other sequencers [77]. Furthermore, the MinION device has potential for use in rapid field-based diagnostic laboratories [78]. The main drawback of long-read sequencing is the higher error rate compared to short read approaches [77].

Third-generation sequencing (MinION) was recently employed to identify BRD pathogens during natural BRD infection with findings showing an 89% concordance between this methodology and the traditional culture method [79]. More recently, a study characterized the bacterial microbiota of the upper and lower respiratory tracts in dairy calves following experimental infection with BoHV-1 [80]. In their study, calves were either inoculated with BoHV-1 or mock-challenged, and nasal swabs, pharyngeal tonsils, and lung tissues were collected for microbial analysis using ONT MinION sequencing. BoHV-1 successfully induced clinical BRD in challenged calves, validating the experimental model. At six days post-challenge, Pasteurella, Streptococcus, and Ruminococcus were the dominant genera identified across nasal, pharyngeal tonsil, and lung samples in infected calves. No significant differences in genus-level bacterial abundance were observed between challenged and control calves, although there was a trend toward altered Shannon diversity in pharyngeal tonsils, suggesting subtle shifts in microbial community structure. These findings indicate that BoHV-1 infection induces BRD without major alterations to the respiratory microbiota at the genus level within six days, while minor diversity changes may reflect early microbial responses to viral infection. The study also highlights the potential of MinION sequencing for rapid characterization of the bovine respiratory microbiome and its application in diagnostic settings.

Studies investigating the bovine respiratory microbiome have consistently shown that microbial diversity and composition are influenced by age, diet, stress, and disease status. BRD-affected cattle often exhibit reduced microbial richness and increased abundance of opportunistic pathogens such as Mycoplasma, Pasteurella, and Histophilus spp., particularly in the upper respiratory tract. However, findings vary across anatomical sites and study designs, with some studies reporting minimal changes in microbial composition following vaccination or antibiotic treatment. Notably, longitudinal studies have highlighted the dynamic nature of microbiomes in response to transportation and weaning stress, suggesting a window of vulnerability for BRD onset. Despite the widespread use of 16S rRNA gene sequencing, limitations in species-level resolution and the inability to detect functional interactions between microbial taxa persist. Emerging third-generation sequencing platforms, such as ONT MinION, offer improved resolution and field applicability, but require further validation. Overall, while the microbiome is clearly implicated in BRD susceptibility and progression, conflicting results and methodological variability highlight the need for standardized protocols and integrative multi-omics approaches to fully elucidate host–microbe–pathogen interactions.

6. Metagenomic Approaches to BRD Virome Characterization

In addition to the bacterial microbiota, the virome of the respiratory tract is also an area of interest. The application of viral metagenomics allows for the detection and characterization of known and novel viruses, offering a more complete understanding of the viral contributors to BRD.

The advent of metagenomic approaches has facilitated the characterization of the respiratory tract virome in bovines affected by BRD, revealing previously unrecognized viral agents [13,15,16,17,18,19,58,81]. In one of the earliest viral metagenomic studies, it was observed that cattle exhibiting clinical signs of BRD did not harbour the viruses traditionally associated with the disease, such as BoHV-1, BPI-3, and BRSV; instead, nucleic acid sequencing from nasopharyngeal swabs identified bovine rhinitis A virus (BRAV) and influenza D virus (IDV), suggesting the involvement of previously unrecognized viral agents [18].

Longitudinal sampling of nasopharyngeal swabs before transportation, on arrival at feedlots, and 40 days post-arrival demonstrated dynamic changes in the respiratory microbiome at all time points, which were attributed to stress and viral infection affecting both host immunity and microbiome composition [15]. Examination of the upper respiratory virome in nasal swabs from cattle in the USA and Mexico revealed geographical differences in viral composition, detecting BoHV-1, BVDV, BRSV, BCoV, IDV, BRV, REO, and BEV, highlighting a broader viral diversity than is currently addressed by vaccination [16].

Analysis of the respiratory virome in 130 post-slaughter beef cattle detected only a limited number of viruses, likely due to prior viral clearance by the host immune system and the preferential colonization of the upper respiratory tract, which reduces viral presence in the lungs. High amounts of non-viral nucleic acids, including host DNA contamination, were also found to reduce sequencing sensitivity [81]. Further studies analyzing deep nasal swabs and tracheal washes from both BRD-affected and clinically healthy cattle, all vaccinated against IBR, BVDV types I and II, BPIV-3, and BRSV, reported that these viruses were not detected; however, BoCV, BRBV, BRAV, and IDV were identified in diseased animals but not in healthy ones [82]. Nasal viromes of cattle on arrival at feedlots showed consistent patterns and further highlighted the role of BCoV, BRBV, BRAV, and IDV in BRD pathogenesis [17].

The use of high-throughput sequencing to characterize the bovine respiratory virome and its potential as a diagnostic tool was demonstrated using the ONT MinION device. When tested on in vitro viral cell cultures and nasal swabs from calves experimentally infected with a single BRD-associated DNA virus, BoHV-1, extensive optimization of Nanopore library preparation protocols, particularly to minimize PCR amplification bias, was required before BoHV-1 could be reliably detected as the dominant virus within approximately 7 h from sample to result [19].

Characterization of the upper respiratory tract virome of feedlot cattle in Australia confirmed associations between certain viral populations and BRD, highlighting the continued complexity and regional variation in viral contributors to the disease [13] Bovine coronavirus (BCoV) variants from nasal swabs of Irish calves with BRD, revealed genomic variation compared with previously reported strains [20]. In a subsequent study, they reported the genome of Ungulate tetraparvovirus 1 (UTPV1) from a nasal swab of a beef-suckler calf, representing one of the first characterizations of this virus in Ireland and contributing to knowledge of cattle virome diversity. Viruses including BRSV, BoHV-1, BVDV and PIV-3 are well documented as BRD opportunistic pathogens [3]. Previously, IDV had been isolated from nasal swabs of symptomatic BRD calves, which exhibited significantly higher levels of IDV RNA than those from healthy animals [16], and it was also shown to be significantly associated with BRD outcomes in Canada [81]. A diverse range of viruses were detected in the upper respiratory tract of Australian feedlot cattle. While some of these viruses are established causes of respiratory disease, the study highlights that numerous other viruses may also influence the development of BRD. Notably, there was a high abundance of bovine nidovirus (BoNV), IDV, BRAV, and BCoV across the samples, with BoNV being the most abundant RNA virus. Additionally, complete or near-complete genomes of BRBV, enterovirus E1, BVDV (sub-genotypes 1a and 1c), and BRSV were obtained, along with partial sequences of other viruses [21].

Like the bacterial microbiota, the bovine respiratory virome also appears to be a complex topic in BRD infection. Although some viruses appear to have an association with BRD, for others their role is not as clear. Furthermore, these identification of relatively newly associated BRD viruses, further highlights the importance of continued BRD diagnostic development that will aid in pathogen surveillance and identification in the future.

Metagenomic studies have expanded the understanding of the bovine respiratory virome, revealing a diverse array of viruses beyond classical BRD pathogens such as BoHV-1, BRSV, and BVDV. Emerging viruses—including bovine rhinitis A and B viruses (BRAV, BRBV), influenza D virus (IDV), and bovine nidovirus (BoNV)—have been increasingly detected in BRD-affected cattle, though their precise roles in disease pathogenesis remain unclear. Geographic variation and temporal dynamics further complicate interpretation, with some viruses appearing more prevalent in specific regions or at different stages of disease development. While high-throughput sequencing technologies, including ONT MinION, have enabled rapid and field-deployable viral detection, challenges persist in distinguishing pathogenic from commensal or opportunistic viruses. Conflicting findings, such as the presence of IDV in both healthy and diseased animals, underscore the need for longitudinal studies and functional validation. Overall, the virome represents a critical but underexplored component of BRD, and its integration with host transcriptomic and microbiome data will be essential to unravel complex host–virus–microbe interactions and improve diagnostic and preventive strategies.

7. Insights into BRD Pathogenesis

BRD pathogenesis typically begins with stress-induced immunosuppression, which compromises mucosal defences and facilitates colonization of the respiratory tract by viral and bacterial pathogens [1,3,12]. Primary viral infections—such as bovine herpesvirus 1 (BoHV-1), bovine respiratory syncytial virus (BRSV), and bovine viral diarrhoea virus (BVDV)—disrupt epithelial integrity and impair innate immune responses, creating a permissive environment for secondary bacterial invasion [3,10,11]. Bacterial pathogens including Mannheimia haemolytica, Pasteurella multocida, Histophilus somni, and Mycoplasma bovis contribute to disease progression through the production of virulence factors such as leukotoxins, adhesins, and endotoxins, which elicit inflammatory responses and tissue damage [28,30]. The resulting pulmonary lesions, characterized by fibrinous pneumonia and necrosis, are hallmarks of advanced BRD [3,14]. Recent advances in molecular diagnostics—such as metagenomics, RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq), and microRNA (miRNA) profiling—have enhanced our understanding of BRD pathogenesis [6,9,10,11,19,30]. These technologies enable the identification of novel pathogens, characterization of host transcriptomic responses, and elucidation of regulatory networks involved in immune modulation. Differential gene expression analyses have revealed activation of interferon signalling, complement pathways, and antimicrobial responses in infected tissues [6,7,8,10]. Additionally, miRNAs have been implicated in post-transcriptional regulation of immune genes, further refining the host response to infection [55,56]. Together, these insights support a systems-level understanding of BRD pathogenesis and inform the development of predictive biomarkers and targeted therapeutic strategies.

Integrating Multi-Omics Approaches to Elucidate BRD Pathogenesis

Understanding BRD requires a systems-level perspective that captures the interplay between host immunity, pathogens, and the respiratory microbiome. Recent advances in transcriptomics, miRNA profiling, metagenomics, and microbiome characterization offer complementary insights, yet these datasets are often analyzed in isolation. Integrating these approaches can reveal mechanistic links between viral and bacterial colonization, host immune modulation, and microbial dysbiosis. Transcriptomic analyses have identified differentially expressed genes (DEGs) associated with innate immunity and interferon signalling in both whole blood and lymphoid tissues during BRD infection [10,11].

Similarly, miRNA studies highlight post-transcriptional regulation of antiviral pathways, with tissue-specific miRNA signatures linked to interferon signalling and pathogen recognition [56]. These host-level datasets provide a foundation for identifying biomarkers and immune pathways responsive to infection.

On the microbial side, 16S rRNA sequencing has demonstrated reduced species richness and increased abundance of opportunistic pathogens such as Mycoplasma and Pasteurella spp. in BRD-affected cattle [14,66]. Meanwhile, viral metagenomics has expanded the known virome, uncovering emerging viruses such as bovine rhinitis A virus (BRAV) and influenza D virus (IDV), which may act as primary or co-infecting agents [16,17,18].

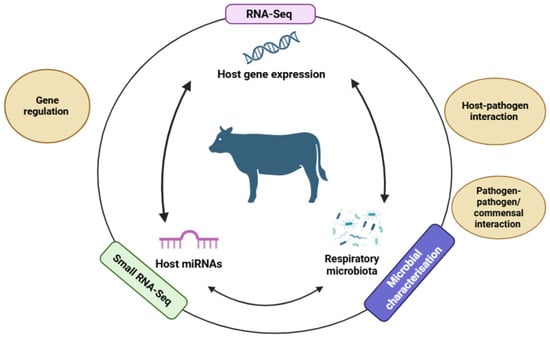

An integrative framework combining these layers—host transcriptome and miRNA profiles, pathogen detection via metagenomics, and microbiome composition—can elucidate host–pathogen–microbiome interactions driving BRD onset and progression. Figure 1 illustrates a conceptual model for multi-omics integration, highlighting key discovery targets and insights to be gained through the integration of these datasets.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model showing how multi-omics datasets could be combined to elucidate host–pathogen–microbiome interactions. Available online: https://app.biorender.com/illustrations/690892e8d877fbf4a3fc7066?slideId=6568a177-bdb9-4864-9990-40c4765f9c74 accessed on: 14 November 2025.

8. Limitations in Current Omics Approaches for BRD Research

Despite significant advances in multi-omics technologies, several limitations constrain the interpretation and reproducibility of findings in BRD research.

Study Design and Sample Size: Many transcriptomic and microbiome studies employ small cohorts or convenience sampling, which restricts statistical power and limits generalizability of results. For example, RNA-Seq investigations of bronchial lymph nodes following experimental BRSV challenge included only 12 infected and 6 control calves [10], while microbiome studies comparing healthy and BRD-affected cattle often rely on single-site sampling [66]. These constraints underscore the need for longitudinal, multi-site designs to capture temporal dynamics and environmental variability.

Bioinformatics Variability: Differences in computational pipelines, normalization strategies, and reference databases can lead to inconsistent outcomes across studies. RNA-Seq workflows vary widely in alignment and differential expression analysis, influencing gene-level interpretations [83,84]. Similarly, microbiome profiling using 16S rRNA sequencing is sensitive to primer choice and taxonomic classifiers, which may bias community composition estimates.

Sequencing Depth and Contamination: Low sequencing depth can obscure rare taxa or low-abundance transcripts, reducing the resolution of microbial and virome analyses. Metagenomic studies of the bovine respiratory virome have reported challenges in detecting low-prevalence viruses and highlighted contamination risks from host DNA and environmental sources [81,85]. These technical limitations emphasize the importance of rigorous quality control, standardized protocols, and transparent reporting to ensure reproducibility and comparability of multi-omics datasets.

9. Conclusions

NGS technologies have allowed for the investigation into the impact of BRD on host animals at the molecular level. Approaches such as RNA-Seq have allowed for the examination of host gene expression in response to BRD infection [6,8,80,81], with genes and biological pathways involved in the host immune response to BRD identified. However, these studies analysed cattle with naturally acquired BRD, where the initial pathogen causing the infection is often unknown. The use of experimental challenge models utilising one or more specific BRD pathogens, coupled with these NGS approaches, offer deeper insight into the host immune response, allowing for the identification of DEGs in response to specific pathogens. Beyond mRNA, non-coding RNAs such as microRNAs (miRNAs), shown to play a role in immune function regulation [86], have also been analysed in cattle with experimentally induced BRD and have shown involvement in processes such as interferon signalling, pathogen recognition, and T-cell responses [56]. The examination of host responses using this approach enables the discovery of biomarkers of BRD infection, which may have potential for use in diagnostic development.

In addition to biomarker discovery, NGS technologies have been used to examine the significance of the URT [87,88] and LRT [89] respiratory tract microbiomes in respiratory tract health and disease susceptibility. Studies have analysed the respiratory microbiota of cattle with naturally occurring BRD [14,66,72], with findings showing certain species to play a role in respiratory health. However, the relative significance of different BRD pathogens remains unclear.

The application of NGS technologies in BRD research has allowed for the generation of many diverse datasets, facilitating the examination of the response to BRD at a deeper level. The integration of both gene expression, as well as microbial datasets provides the potential to further understand the cross-system response of BRD, not only at the host level, but also at a microbial level, through the characterisation of the microbiota residing within the hosts respiratory tract. The integration of these data will provide a deeper understanding of the impact of BRD on hosts themselves, as well as their respiratory microbiomes, which consequently may offer new insights into potential therapeutic targets.

The topics reviewed in this manuscript, including transcriptomics, metagenomics, microbiome dynamics, and molecular diagnostics, collectively support the stated objective by providing a comprehensive overview of the host–pathogen interactions and technological advances that have enhanced the understanding of BRD pathogenesis and diagnostic capabilities.

10. Future Directions and Research Priorities

BRD remains a multifactorial challenge requiring integrated diagnostic and management strategies. While significant progress has been made in applying transcriptomics, miRNA profiling, metagenomics, and microbiome characterization, these approaches are often siloed, limiting their translational impact. To enhance the impact of these approaches, future research should focus on the following priorities:

- Standardization of Protocols:

There is a critical need to harmonize sampling methodologies, sequencing depth parameters, and bioinformatics pipelines. Standardization will reduce inter-study variability and improve reproducibility, thereby facilitating cross-comparative analyses and meta-analytical evaluations [83,84].

- 2.

- Multi-Omics Data Integration:

Developing robust frameworks for the integration of host transcriptomic and miRNA datasets with microbial and virome profiles is essential. Such integrative models should employ network-based analytics and machine learning techniques to elucidate host–pathogen–microbiome interactions, identify diagnostic biomarkers, and enable predictive modeling of disease outcomes [13,90].

- 3.

- Translational Applications:

To bridge the gap between research and field implementation, omics-derived insights must be translated into practical tools for BRD control. This includes the development of point-of-care diagnostic platforms utilizing portable sequencing technologies [10,11,19], as well as microbiome-informed interventions such as probiotics or targeted therapeutics [66].

By advancing these strategic priorities, the field will advance toward a systems-level understanding of BRD pathogenesis and enable evidence-based solutions for disease prevention and control.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.O., B.E., S.M.W., and D.W.M.; methodology, S.O. and B.E.; writing—original draft preparation, S.O., B.E., S.M.W., and D.W.M.; writing—review and editing, S.O., B.E., S.M.W., and D.W.M.; visualization, S.O., B.E., S.M.W., and D.W.M.; supervision, S.M.W., B.E., and D.W.M.; funding acquisition, S.M.W. and B.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors gratefully acknowledge funding from; Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine (DAFM) US–Ireland R&D partnership call (Project 16/RD/US-ROI/11), the US–Ireland Tri Partite Grant (2018US-IRL200), and the European Union Horizons 2020, HoloRuminant project (Grant agreement No. 101000213).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this paper:

| BCoV | Bovine coronavirus |

| BoHV-1 | Bovine herpesvirus 1 |

| BPI3V | Bovine parainfluenza 3 |

| BRAV1 | Bovine rhinitis A virus 1 |

| BRAV2 | Bovine rhinitis A virus 2 |

| BRD | Bovine respiratory disease |

| BRSV | Bovine respiratory syncytial virus |

| BVDV | Bovine viral diarrhoea virus |

| cDNA | Complementary DNA) |

| LAMP | Loop-mediated isothermal amplification |

| LASL | Linker Amplified Shotgun Library |

| LRT | Lower respiratory tract |

| MDA | Multiple Displacement Amplification |

| MLN | Mediastinal lymph node |

| MiRNA | MicroRNA |

| MLV | Modified live vaccine |

| mRNA | Messenger RNA |

| NCBI | National Center for Biotechnology Information |

| OTUs | Operational Taxonomic Units |

| RNA | Ribonucleic acid |

| RNA-Seq | RNA-Sequencing |

| SISPA | Sequence-Independent Single-Primer Amplification |

| URT | Upper respiratory tract |

| US | United States |

References

- Pardon, B.; Buczinski, S. Bovine respiratory disease diagnosis: What progress has been made in infectious diagnosis? Vet. Clin. North Am. Food Anim. Pract. 2020, 36, 425–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamel, M.S.; Davidson, J.L.; Verma, M.S. Strategies for bovine respiratory disease (BRD) diagnosis and prognosis: A comprehensive overview. Animals 2024, 14, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Donoghue, S.; Waters, S.M.; Morris, D.W.; Earley, B. A comprehensive review: Bovine respiratory disease, current insights into epidemiology, diagnostic challenges, and vaccination. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thonur, L.; Maley, M.; Gilray, J.; Crook, T.; Laming, E.; Turnbull, D.; Nath, M.; Willoughby, K. One-step multiplex real-time RT-PCR for the detection of bovine respiratory syncytial virus, bovine herpesvirus 1, and bovine parainfluenza virus 3. BMC Vet. Res. 2012, 8, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, F.; Tao, C.; Xiao, R.; Huang, Y.; Yuan, W.; Wang, Z.; Jia, H. Development of a Multiplex Real-Time PCR Assay for the detection of eight pathogens associated with bovine respiratory disease complex from clinical samples. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.Z.; Srithayakumar, V.; Jiminez, J.; Jin, W.; Hosseini, A.; Raszek, M.; Orsel, K.; Guan, L.L.; Plastow, G. Longitudinal blood transcriptomic analysis to identify molecular regulatory patterns of bovine respiratory disease in beef cattle. Genomics 2020, 112, 3968–3977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, M.A.; Woolums, A.R.; Swiderski, C.E.; Finley, A.; Perkins, A.D.; Nanduri, B.; Karisch, B.B. Hematological and gene co-expression network analyses of high-risk beef cattle defines immunological mechanisms and biological complexes involved in bovine respiratory disease and weight gain. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0277033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiminez, J.; Timsit, E.; Orsel, K.; van der Meer, F.; Guan, L.L.; Plastow, G. Whole-blood transcriptome analysis of feedlot cattle with and without bovine respiratory disease. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tizioto, P.C.; Kim, J.; Seabury, C.M.; Schnabel, R.D.; Gershwin, L.J.; Van Eenennaam, A.L.; Toaff-Rosenstein, R.; Neibergs, H.L.; Team, B.R.D.C.C.A.P.R.; Taylor, J.F. Immunological response to single pathogen challenge with agents of the bovine respiratory disease complex: An RNA-sequence analysis of the bronchial lymph node transcriptome. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0131459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, D.; Earley, B.; McCabe, M.S.; Lemon, K.; Duffy, C.; McMenamy, M.; Cosby, S.L.; Kim, J.; Blackshields, G.; Taylor, J.F. Experimental challenge with bovine respiratory syncytial virus in dairy calves: Bronchial lymph node transcriptome response. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 14736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donoghue, S.; Earley, B.; Johnston, D.; McCabe, M.S.; Kim, J.W.; Taylor, J.F.; Duffy, C.; Lemon, K.; McMenamy, M.; Cosby, S.L.; et al. Whole blood transcriptome analysis in dairy calves experimentally challenged with bovine herpesvirus 1 (BoHV-1) and comparison to a bovine respiratory syncytial virus (BRSV) Challenge. Front. Genet. 2023, 14, 1092877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, G.M.; O’Neill, R.G.; More, S.J.; McElroy, M.C.; Earley, B.; Cassidy, J.P. Evolving views on bovine respiratory disease: An appraisal of selected key pathogens–Part 1. Vet. J. 2016, 217, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrose, R.K.; Blakebrough-Hall, C.; Gravel, J.L.; Gonzalez, L.A.; Mahony, T.J. Characterisation of the upper respiratory tract virome of feedlot cattle and its association with bovine respiratory disease. Viruses 2023, 15, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, D.; Earley, B.; Cormican, P.; Murray, G.; Kenny, D.A.; Waters, S.M.; McGee, M.; Kelly, A.K.; McCabe, M.S. Illumina MiSeq 16S Amplicon sequence analysis of bovine respiratory disease associated bacteria in lung and mediastinal lymph node tissue. BMC Vet. Res. 2017, 13, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timsit, E.; Workentine, M.; Schryvers, A.B.; Holman, D.B.; van der Meer, F.; Alexander, T.W. Evolution of the nasopharyngeal microbiota of beef cattle from weaning to 40 days after arrival at a feedlot. Vet. Microbiol. 2016, 187, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, N.; Cernicchiaro, N.; Torres, S.; Li, F.; Hause, B.M. Metagenomic Characterization of the virome associated with bovine respiratory disease in feedlot cattle identified novel viruses and suggests an etiologic role for influenza D virus. J. Gen. Virol. 2016, 97, 1771–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Hill, J.E.; Alexander, T.W.; Huang, Y. The nasal viromes of cattle on arrival at western Canadian feedlots and their relationship to development of bovine respiratory disease. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2021, 68, 2209–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, T.F.F.; Kondov, N.O.; Deng, X.; Van Eenennaam, A.; Neibergs, H.L.; Delwart, E. A Metagenomics and case-control study to identify viruses associated with bovine respiratory disease. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 5340–5349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esnault, G.; Earley, B.; Cormican, P.; Waters, S.M.; Lemon, K.; Cosby, S.L.; Lagan, P.; Barry, T.; Reddington, K.; McCabe, M.S. Assessment of Rapid MinION nanopore DNA virus metagenomics using calves experimentally infected with bovine herpes virus-1. Viruses 2022, 14, 1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ní Dhufaigh, K.; McCabe, M.; Cormican, P.; Cuevas-Gomez, I.; McGee, M.; McDaneld, T.; Earley, B. Genome sequence of bovine coronavirus variants from the nasal virome of Irish beef suckler and pre-weaned dairy calves clinically diagnosed with bovine respiratory disease. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 2022, 11, e00821-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, B.P.; Frost, M.J.; Anantanawat, K.; Jaya, F.; Batterham, T.; Djordjevic, S.P.; Chang, W.S.; Holmes, E.C.; Darling, A.E.; Kirkland, P.D. Expanding the range of the respiratory infectome in australian feedlot cattle with and without respiratory disease using metatranscriptomics. Microbiome 2023, 11, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gershwin, L.J.; Van Eenennaam, A.L.; Anderson, M.L.; McEligot, H.A.; Shao, M.X.; Toaff-Rosenstein, R.; Taylor, J.F.; Neibergs, H.L.; Womack, J.; Bovine Respiratory Disease Complex Coordinated Agricultural Project Research Team. Single pathogen challenge with agents of the bovine respiratory disease complex. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0142479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poonsuk, K.; Kordik, C.; Hille, M.; Cheng, T.-Y.; Crosby, W.B.; Woolums, A.R.; Clawson, M.L.; Chitko-McKown, C.; Brodersen, B.; Loy, J.D. Detection of Mannheimia haemolytica-specific IgG, IgM and IgA in sera and their relationship to respiratory disease in cattle. Animals 2023, 13, 1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werid, G.M.; Miller, D.; Hemmatzadeh, F.; Messele, Y.E.; Petrovski, K. An overview of the detection of bovine respiratory disease complex pathogens using immunohistochemistry: Emerging trends and opportunities. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 2023, 36, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Singh, R.; Singh, K.P.; Singh, V.; Malik, Y.P.S.; Kamdi, B.; Singh, R.; Kashyap, G. Immunohistochemical and molecular detection of natural cases of bovine rotavirus and coronavirus infection causing enteritis in dairy calves. Microb. Pathog. 2020, 138, 103814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fulton, R.W.; Confer, A.W. Laboratory test descriptions for bovine respiratory disease diagnosis and their strengths and weaknesses: Gold standards for diagnosis, do they exist? Can. Vet. J. 2012, 53, 754–761. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Loy, J.D. Development and application of molecular diagnostics and proteomics to bovine respiratory disease (BRD). Anim. Health Res. Rev. 2020, 21, 164–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishimoto, M.; Tsuchiaka, S.; Rahpaya, S.S.; Hasebe, A.; Otsu, K.; Sugimura, S.; Kobayashi, S.; Komatsu, N.; Nagai, M.; Omatsu, T.; et al. Development of a One-Run Real-Time PCR detection system for pathogens associated with bovine respiratory disease complex. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2017, 79, 517–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisselink, H.J.; Cornelissen, J.B.; van der Wal, F.J.; Kooi, E.A.; Koene, M.G.; Bossers, A.; Smid, B.; de Bree, F.M.; Antonis, A.F. Evaluation of a Multiplex Real-Time PCR for detection of four bacterial agents commonly associated with bovine respiratory disease in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. BMC Vet. Res. 2017, 13, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goto, Y.; Yaegashi, G.; Fukunari, K.; Suzuki, T. Design of a Multiplex Quantitative Reverse Transcription-PCR system to simultaneously detect 16 pathogens associated with bovine respiratory and enteric diseases. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2020, 129, 832–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, W.; Yang, M.; Lin, J.; Xue, F.; Zhu, Y.; Yin, X. Development of a one-step multiplex real-time PCR assay for the detection of viral pathogens associated with the bovine respiratory disease complex. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 825257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual-Garrigos, A.; Maruthamuthu, M.K.; Ault, A.; Davidson, J.L.; Rudakov, G.; Pillai, D.; Koziol, J.; Schoonmaker, J.P.; Johnson, T.; Verma, M.S. On-farm colorimetric detection of Pasteurella multocida, Mannheimia haemolytica, and Histophilus somni in Crude Bovine Nasal Samples. Vet. Res. 2021, 52, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, S.; Pascual-Garrigos, A.; Brouwer, H.; Pillai, D.; Koziol, J.; Ault, A.; Schoonmaker, J.; Johnson, T.; Verma, M.S. Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification for the detection of Pasteurella multocida, Mannheimia haemolytica, and Histophilus somni in Bovine Nasal Samples. ACS Agric. Sci. Technol. 2021, 1, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrini, S.; Iscaro, C.; Righi, C. Antibody responses to bovine alphaherpesvirus 1 (BoHV-1) in passively immunized calves. Viruses 2019, 11, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Huang, Y.; Godson, D.L.; Fernando, C.; Alexander, T.W.; Hill, J.E. Assessment of metagenomic sequencing and qPCR for detection of influenza D virus in bovine respiratory tract samples. Viruses 2020, 12, 814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, A.J.; Raskin, L. PCR biases distort bacterial and archaeal community structure in pyrosequencing datasets. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e43093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, J.D.; Bloom, R.J.; Jiang, S.; Durand, H.K.; Dallow, E.; Mukherjee, S.; David, L.A. Measuring and mitigating PCR bias in microbiota datasets. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2021, 17, e1009113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kralik, P.; Ricchi, M. A Basic Guide to Real-Time PCR in Microbial Diagnostics: Definitions, parameters, and everything. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behjati, S.; Tarpey, P.S. What is next generation sequencing? Arch. Dis. Child. Educ. Pract. Ed. 2013, 98, 236–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, N.; Kumar, P. Integrated COVID-19 Predictor: Differential expression analysis to reveal potential biomarkers and prediction of Coronavirus Using RNA-Seq Profile Data. Comput. Biol. Med. 2022, 147, 105684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, I.H.; Shi, Y.; Jiang, H.; Kumar-Sinha, C.; Chinnaiyan, A.M. RNA-Seq accurately identifies cancer biomarker signatures to distinguish tissue of origin. Neoplasia 2014, 16, 918–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Wang, H.; Mao, L.; Yu, H.; Yu, X.; Sun, Z.; Qian, X.; Cheng, S.; Chen, S.; Chen, J.; et al. Rapid genomic characterization of SARS-CoV-2 viruses from clinical specimens using nanopore sequencing. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 17492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behura, S.K.; Tizioto, P.C.; Kim, J.; Grupioni, N.V.; Seabury, C.M.; Schnabel, R.D.; Gershwin, L.J.; Van Eenennaam, A.L.; Toaff-Rosenstein, R.; Neibergs, H.L.; et al. Tissue tropism in host transcriptional response to members of the bovine respiratory disease complex. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 17938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, M.A.; Woolums, A.R.; Swiderski, C.E.; Perkins, A.D.; Nanduri, B.; Smith, D.R.; Karisch, B.B.; Epperson, W.B.; Blanton, J.R., Jr. Whole blood transcriptomic analysis of beef cattle at arrival identifies potential predictive molecules and mechanisms that indicate animals that naturally resist bovine respiratory disease. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0227507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, M.A.; Woolums, A.R.; Swiderski, C.E.; Perkins, A.D.; Nanduri, B.; Smith, D.R.; Karisch, B.B.; Epperson, W.B.; Blanton, J.R. Comprehensive at-arrival transcriptomic analysis of post-weaned beef cattle uncovers type I interferon and antiviral mechanisms associated with bovine respiratory disease mortality. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0250758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, D.; Earley, B.; McCabe, M.S.; Kim, J.; Taylor, J.F.; Lemon, K.; Duffy, C.; McMenamy, M.; Cosby, S.L.; Waters, S.M. Messenger RNA biomarkers of bovine respiratory syncytial virus infection in the whole blood of dairy calves. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 9392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Li, X.; Jin, M.; Liu, Y.; He, Y.; Jia, N.; Cui, X.; Liu, Y.; Hu, G.; Yu, Q. Identification of potential biomarkers for early diagnosis of schizophrenia through RNA sequencing analysis. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2022, 147, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M.M.; Woolums, A.R.; Karisch, B.B.; Harvey, K.M.; Capik, S.F.; Scott, M.A. Influence of the at-arrival host transcriptome on bovine respiratory disease incidence during backgrounding. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glazov, E.A.; Kongsuwan, K.; Assavalapsakul, W.; Horwood, P.F.; Mitter, N.; Mahony, T.J. Repertoire of bovine mirna and mirna-like small regulatory rnas expressed upon viral infection. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e6349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, S.; Tsao, M.-S.; McPherson, J.D. Optimization of miRNA-seq data preprocessing. Brief. Bioinform. 2015, 16, 950–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chen, J.; Sen, S. MicroRNA as biomarkers and diagnostics. J. Cell. Physiol. 2016, 231, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W. MicroRNAs: Biomarkers, Diagnostics, and Therapeutics. In Bioinformatics in MicroRNA Research; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 57–67. [Google Scholar]

- Miretti, S.; Lecchi, C.; Ceciliani, F.; Baratta, M. MicroRNAs as Biomarkers for animal health and welfare in livestock. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 578193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, H.; Gao, Q.; Peng, X.; Sun, Y.; Han, T.; Zhao, B.; Liu, Y.; Wang, C.; Song, X.; Wu, J. Circulating MicroRNAs as potential biomarkers for veterinary infectious diseases. Front. Vet. Sci. 2017, 4, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casas, E.; Cai, G.; Kuehn, L.A.; Register, K.B.; McDaneld, T.G.; Neill, J.D. Association of MicroRNAs with antibody response to Mycoplasma bovis in beef cattle. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0161651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, D.; Earley, B.; McCabe, M.S.; Kim, J.; Taylor, J.F.; Lemon, K.; McMenamy, M.; Duffy, C.; Cosby, S.L.; Waters, S.M. Elucidation of the host bronchial lymph node miRNA transcriptome response to bovine respiratory syncytial virus. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, P.; Zhao, M.; He, W.; He, H.; Wang, H. Cellular MicroRNA bta-miR-2361 Inhibits Bovine Herpesvirus 1 replication by directly targeting EGR1 Gene. Vet. Microbiol. 2019, 233, 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lederberg, J.; McCray, A.T. Ome Sweet Omics—A genealogical treasury of words. Scientist 2001, 15, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Zeineldin, M.; Lowe, J.; Aldridge, B. Contribution of the mucosal microbiota to bovine respiratory health. Trends Microbiol. 2019, 27, 753–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouhy, F.; Clooney, A.G.; Stanton, C.; Claesson, M.J.; Cotter, P.D. 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing of mock microbial populations—Impact of DNA extraction method, primer choice and sequencing platform. BMC Microbiol. 2016, 16, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Li, Y.; Li, S.; Hu, N.; He, Y.; Pong, R.; Lin, D.; Lu, L.; Law, M. Comparison of next-generation sequencing systems. Biomed. Res. Int. 2012, 2012, 251364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klindworth, A.; Pruesse, E.; Schweer, T.; Peplies, J.; Quast, C.; Horn, M.; Glöckner, F.O. Evaluation of general 16S ribosomal RNA Gene PCR primers for classical and next-generation sequencing-based diversity studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, S.F.; Teixeira, A.G.; Higgins, C.H.; Lima, F.S.; Bicalho, R.C. The Upper Respiratory tract microbiome and its potential role in bovine respiratory disease and otitis media. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 29050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeineldin, M.; Lowe, J.; de Godoy, M.; Maradiaga, N.; Ramirez, C.; Ghanem, M.; Abd El-Raof, Y.; Aldridge, B. Disparity in the nasopharyngeal microbiota between healthy cattle on feed, at entry processing, and with respiratory disease. Vet. Microbiol. 2017, 208, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMullen, C.; Orsel, K.; Alexander, T.W.; van der Meer, F.; Plastow, G.; Timsit, E. Evolution of the nasopharyngeal bacterial microbiota of beef calves from spring processing to 40 days after feedlot arrival. Vet. Microbiol. 2018, 225, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMullen, C.; Orsel, K.; Alexander, T.W.; van der Meer, F.; Plastow, G.; Timsit, E. Comparison of the nasopharyngeal bacterial microbiota of beef calves raised without the use of antimicrobials between healthy calves and those diagnosed with bovine respiratory disease. Vet. Microbiol. 2019, 231, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centeno-Delphia, R.E.; Glidden, N.; Long, E.; Ellis, A.; Hoffman, S.; Mosier, K.; Ulloa, N.; Cheng, J.J.; Davidson, J.L.; Mohan, S. Nasal pathobiont abundance is a moderate feedlot-dependent indicator of bovine respiratory disease in beef cattle. Anim. Microbiome 2025, 7, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- McDaneld, T.G.; Workman, A.M.; Chitko-McKown, C.G.; Kuehn, L.A.; Dickey, A.; Bennett, G.L. Detection of Mycoplasma bovirhinis and Bovine Coronavirus in an outbreak of bovine respiratory disease in nursing beef calves. Front. Microbiomes 2022, 1, 1051241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAtee, T.B.; Pinnell, L.J.; Powledge, S.A.; Wolfe, C.A.; Morley, P.S.; Richeson, J.T. Effects of respiratory virus vaccination and bovine respiratory disease on the respiratory microbiome of feedlot cattle. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1203498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabry, I.; Zeineldin, M.; Kamal, M.; Hefnawy, A.; El-Attar, H.; Abdelraof, Y.; Ghanem, M. Comparative evaluation of lower respiratory tract microbiota in healthy and BRD-affected calves in Egypt. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2025, 57, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicola, I.; Cerutti, F.; Grego, E.; Bertone, I.; Gianella, P.; D’Angelo, A.; Peletto, S. Characterization of the upper and lower respiratory tract microbiota in piedmontese Calves. Microbiome 2017, 5, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMullen, C.; Alexander, T.W.; Léguillette, R.; Workentine, M.; Timsit, E. Topography of the Respiratory Tract Bacterial Microbiota in Cattle. Microbiome 2020, 8, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMullen, C.; Alexander, T.W.; Orsel, K.; Timsit, E. Progression of Nasopharyngeal and tracheal bacterial microbiotas of feedlot cattle during development of bovine respiratory disease. Vet. Microbiol. 2020, 248, 108826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Zaheer, R.; Kinnear, A.; Jelinski, M.; McAllister, T.A. Comparative microbiomes of the respiratory tract and joints of feedlot cattle mortalities. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodwin, S.; McPherson, J.D.; McCombie, W.R. Coming of Age: Ten Years of Next-Generation Sequencing Technologies. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2016, 17, 333–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, T.; Zhou, W. The third generation sequencing: The advanced approach to genetic diseases. Transl. Pediatr. 2020, 9, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kono, N.; Arakawa, K. Nanopore Sequencing: Review of potential applications in functional genomics. Dev. Growth Differ. 2019, 61, 316–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, M.C.; Zwirglmaier, K.; Vette, P.; Holowachuk, S.A.; Stoecker, K.; Genzel, G.H.; Antwerpen, M.H. MinION as part of a biomedical rapidly deployable laboratory. J. Biotechnol. 2017, 250, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamura, S.; Fukuda, A.; Usui, M. Rapid detection of causative bacteria including multiple infections of bovine respiratory disease using 16S rRNA amplicon-based nanopore sequencing. Vet. Res. Commun. 2024, 48, 3873–3881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donoghue, S.; Earley, B.; McCabe, M.S.; Johnston, D.; Cosby, S.L.; Lemon, K.; Kim, J.; Taylor, J.F.; Morris, D.; Waters, S. Characterisation of the bacterial microbiota of nasal swab and pharyngeal tonsil samples from dairy calves following experimental challenge with bovine herpesvirus 1 (BoHV-1). Anim.–Sci. Proc. 2025, 16, 64–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Hill, J.E.; Fernando, C.; Alexander, T.W.; Timsit, E.; van der Meer, F.; Huang, Y. Respiratory viruses identified in western Canadian beef cattle by metagenomic sequencing and their association with bovine respiratory disease. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2019, 66, 1379–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Hill, J.E.; Godson, D.L.; Ngeleka, M.; Fernando, C.; Huang, Y. The pulmonary virome, bacteriological and histopathological findings in bovine respiratory disease from western Canada. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2020, 67, 924–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa-Silva, J.; Domingues, D.; Lopes, F.M. RNA-Seq Differential Expression Analysis: An Extended Review and a Software Tool. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0190152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, D.; Chhugani, K.; Chang, Y.; Karlsberg, A.; Loeffler, C.; Zhang, J.; Muszyńska, A.; Munteanu, V.; Yang, H.; Rotman, J.; et al. RNA-seq Data science: From raw data to effective interpretation. Front. Genet. 2023, 14, 997383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, J.E.; Castañeda, S.; Camargo, M.; García-Corredor, D.J.; Muñoz, M.; Ramírez, J.D. Exploring viral diversity and metagenomics in livestock: Insights into disease emergence and spillover risks in cattle. Vet. Res. Commun. 2024, 48, 2029–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonkoly, E.; Ståhle, M.; Pivarcsi, A. MicroRNAs and immunity: Novel players in the regulation of normal immune function and inflammation. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2008, 18, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holman, D.B.; McAllister, T.A.; Topp, E.; Wright, A.-D.G.; Alexander, T.W. The Nasopharyngeal microbiota of feedlot cattle that develop bovine respiratory disease. Vet. Microbiol. 2015, 180, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDaneld, T.G.; Kuehn, L.A.; Keele, J.W. Evaluating the Microbiome of Two Sampling Locations in the Nasal Cavity of Cattle with Bovine Respiratory Disease Complex (BRDC)1. J. Anim. Sci. 2018, 96, 1281–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klima, C.L.; Holman, D.B.; Ralston, B.J.; Stanford, K.; Zaheer, R.; Alexander, T.W.; McAllister, T.A. Lower respiratory tract microbiome and resistome of bovine respiratory disease mortalities. Microb. Ecol. 2019, 78, 446–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Huang, F.; Gan, L.; Zhou, X.; Gou, L.; Xie, Y.; Guo, H.; Fang, J.; Zuo, Z. Multi-omics investigation into long-distance road transportation effects on respiratory health and immunometabolic responses in calves. Microbiome 2024, 12, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).