Serum Paraoxonase-1 (PON-1) in Dogs: Frequency of Decreased Values in Clinical Practice and Prognostic Significance

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Sample Collection

- (1)

- Immediate follow-up information, used to stratify dogs into two groups—hospitalized vs. non-hospitalized.

- (2)

- Outcome data, used to classify cases as survivors or non-survivors.

2.2. Measurement of PON-1 Activity

2.3. Statistical Analysis

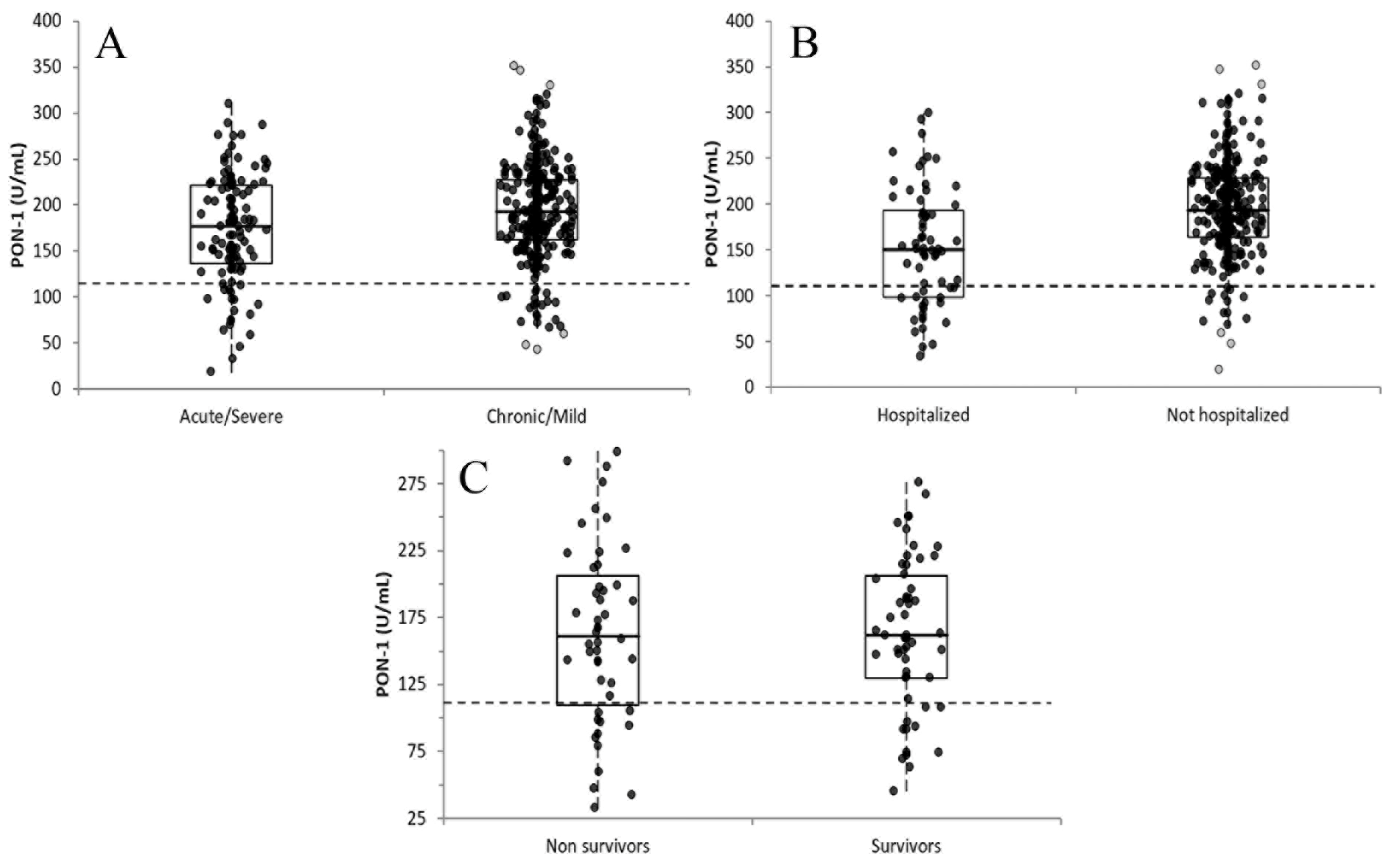

- Disease severity: dogs with acute or severe disease (e.g., life-threatening or septic conditions, acute infections, pulmonary edema, or end-stage neoplasia with systemic involvement) versus those with chronic or mild disease (e.g., non-traumatic orthopedic disorders, neoplasia without systemic complications), or dogs included in the absence of clinical signs (e.g., health checks, screening visits);

- Hospitalization status: hospitalized versus non-hospitalized dogs following initial evaluation;

- Outcome: survivors (improved clinical condition and/or discharge) versus non-survivors (spontaneous death or euthanasia related to the clinical episode), irrespective of hospitalization status.

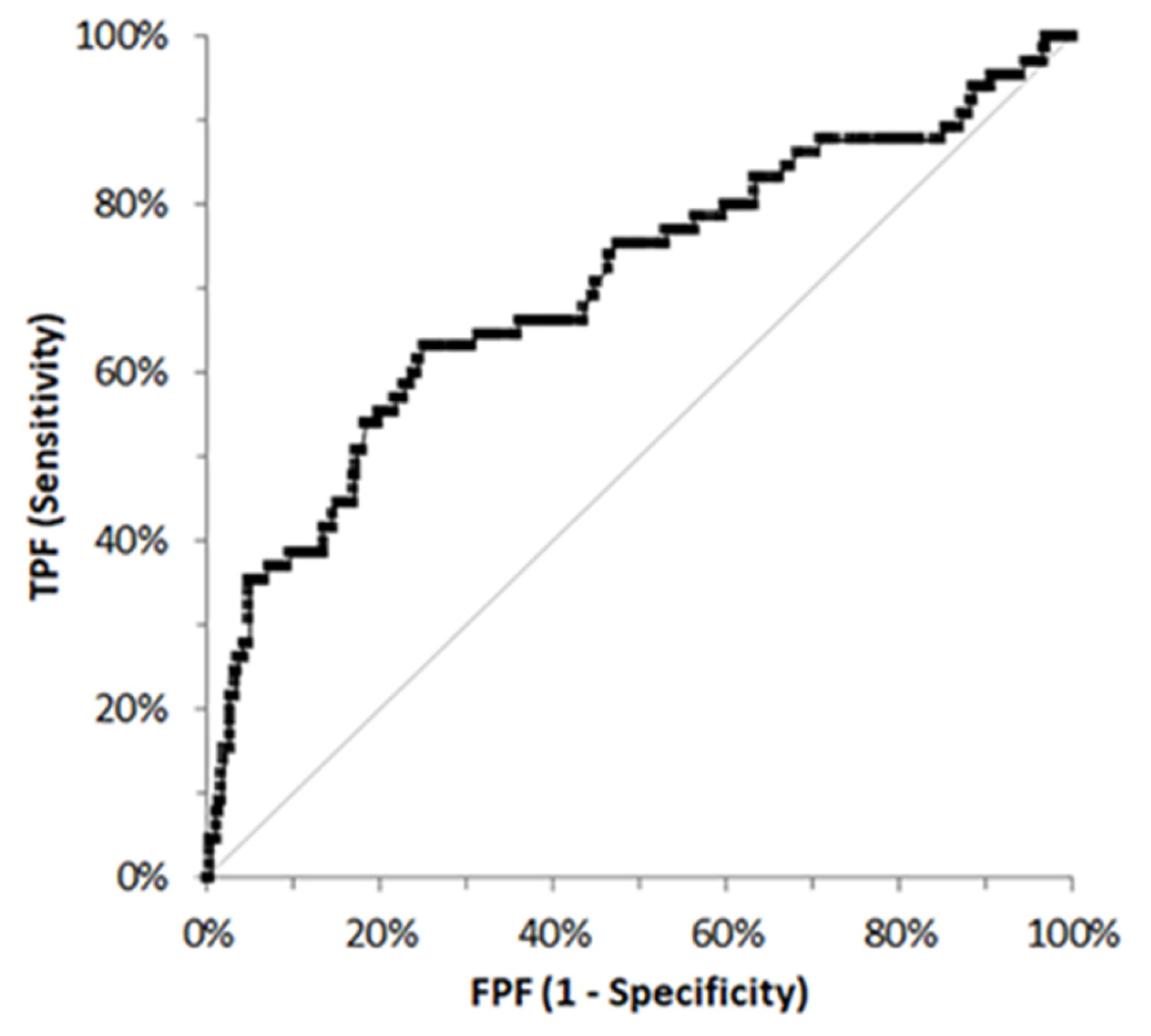

- True positives: hospitalized dogs with PON-1 values below the operating point;

- False positives: non-hospitalized dogs with PON-1 values below the operating point;

- False negatives: hospitalized dogs with PON-1 values above the operating point;

- True negatives: non-hospitalized dogs with PON-1 values above the operating point.

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

3.2. PON-1 Activity in the Different Groups

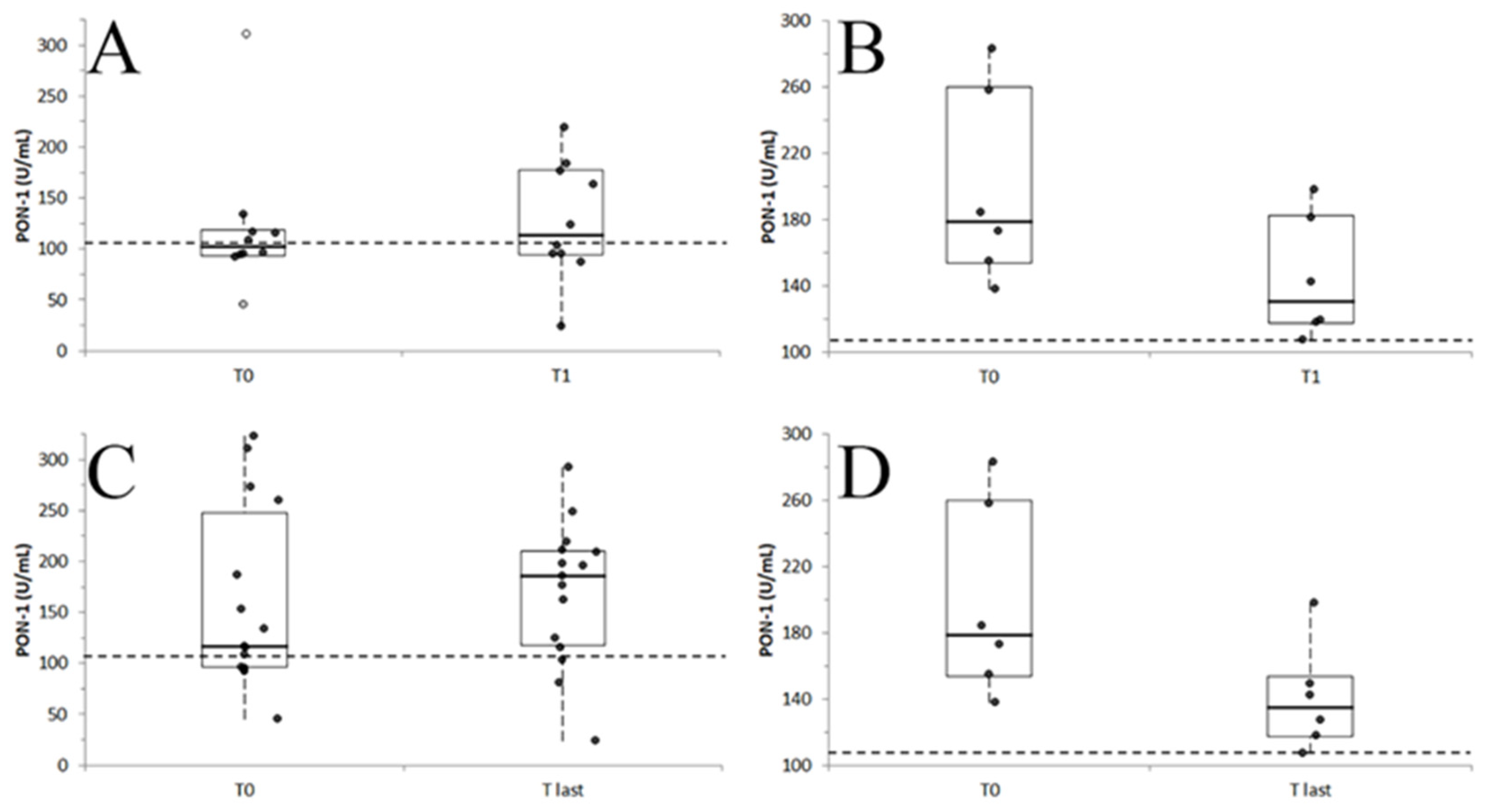

3.3. PON-1 Activity During the Follow Up

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AKI | Acute kidney injury |

| BOAS | Brachycephalic Obstructive Airway Syndrome |

| CKD | Chronic kidney disease |

| CKCS | Cavalier King Charles Spaniel |

| CMO | Cranio-mandibular osteopathy |

| HDL | High density lipoprotein |

| LDL | Low density lipoprotein |

| MVD | Mitral valve disease |

| PDA | Patent ductus arteriosus |

| PON | Paraoxonase |

| PON-1 | Paraoxonase-1 |

| SAA | Serum amyloid A |

| VTH | Veterinary teaching hospital |

| WHWT | West Highland White Terrier |

References

- Rossi, G.; Richardson, A.; Jamaludin, H.; Secombe, C. Preanalytical variables affecting the measurement of serum paraoxonase-1 activity in horses. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 2021, 33, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, C.L.; La Du, B.N. Calcium binding by human and rabbit serum paraoxonases. Structural stability and enzymatic activity. Drug Metab. Dispos. 1998, 26, 653–660. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Josse, D.; Masson, P.; Bartels, C.; Lockridge, O. PON1 Structure. In Paraoxonase (PON1) in Health and Disease: Basic and Clinical Aspects, 1st ed.; Costa, L.G., Furlong, C.E., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 27–52. [Google Scholar]

- Harel, M.; Aharoni, A.; Gaidukov, L.; Brumshtein, B.; Khersonsky, O.; Meged, R.; Dvir, H.; Ravelli, R.B.; McCarthy, A.; Toker, L.; et al. Structure and evolution of the serum paraoxonase family of detoxifying and anti-atherosclerotic enzymes. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2004, 1, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, A.D.; Berliner, J.A.; Hama, S.Y.; La Du, B.N.; Faull, K.F.; Fogelman, A.M.; Navab, M. Protective effect of high density lipoprotein associated paraoxonase. Inhibition of the biological activity of minimally oxidized low density lipoprotein. J. Clin. Investig. 1995, 96, 2882–2891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, G.; Giordano, A.; Pezzia, F.; Kjelgaard-Hansen, M.; Paltrinieri, S. Serum paraoxonase 1 activity in dogs: Preanalytical and analytical factors and correlation with C-reactive protein and alpha-2-globulin. Vet. Clin. Pathol. 2013, 42, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Lenten, B.J.; Hama, S.Y.; de Beer, F.C.; Stafforini, D.M.; McIntyre, T.M.; Prescott, S.M.; La Du, B.N.; Fogelman, A.M.; Navab, M. Antiinflammatory HDL becomes pro-inflammatory during the acute phase response. Loss of protective effect of HDL against LDL oxidation in aortic wall cell cocultures. J. Clin. Investig. 1995, 96, 2758–2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kedage, V.; Muttigi, M.S.; Shetty, M.S.; Suvarna, R.; Rao, S.S.; Joshi, C.; Prakash, M. Serum paraoxonase 1 activity status in patients with liver disorders. Saudi J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 16, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adiga, U.; Banawalikar, N.; Menambath, D.T. Association of paraoxonase 1 activity and insulin resistance models in type 2 diabetes mellitus: Cross-sectional study. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. 2022, 85, 77–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, R.; Uyanikoglu, A.; Cindoglu, C.; Eren, M.A.; Koyuncu, I. Evaluation of the paraoxonase-1 level in patients with acute pancreatitis. Curr. Health Sci. J. 2023, 49, 28–32. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, B.F.; Narciso, L.G.; Melo, L.M.; Preve, P.P.; Bosco, A.M.; Lima, V.M.; Ciarlini, P.C. Leishmaniasis causes oxidative stress and alteration of oxidative metabolism and viability of neutrophils in dogs. Vet. J. 2013, 198, 599–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, A.J.; Krueger, M.; Krueger, M. Decreased level of serum paraoxonase (PON) activity in dogs with dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM). J. Vet. Med. Anim. Health 2014, 6, 245–250. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, G.; Kuleš, J.; Rafaj, R.B.; Mrljak, V.; Lauzi, S.; Giordano, A.; Paltrinieri, S. Relationship between paraoxonase 1 activity and high density lipoprotein concentration during naturally occurring babesiosis in dogs. Res. Vet. Sci. 2014, 97, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocaturk, M.; Tvarijonaviciute, A.; Martinez-Subiela, S.; Tecles, F.; Eralp, O.; Yilmaz, Z.; Ceron, J.J. Inflammatory and oxidative biomarkers of disease severity in dogs with parvoviral enteritis. J. Small Anim. Pract. 2015, 56, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tvarijonaviciute, A.; Garcia-Martinez, J.D.; Caldin, M.; Martinez-Subiela, S.; Tecles, F.; Pastor, J.; Ceron, J.J. Serum paraoxonase 1 (PON1) activity in acute pancreatitis of dogs. J. Small Anim. Pract. 2015, 56, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karnezi, D.; Ceron, J.J.; Theodorou, K.; Leontides, L.; Siarkou, V.I.; Martinez, S.; Tvarijonaviciute, A.; Harrus, S.; Koutinas, C.K.; Pardali, D.; et al. Acute phase protein and antioxidant responses in dogs with experimental acute monocytic ehrlichiosis treated with rifampicin. Vet. Microbiol. 2016, 184, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuleš, J.; de Torre-Minguela, C.; Barić Rafaj, R.; Gotić, J.; Nižić, P.; Ceron, J.J.; Mrljak, V. Plasma biomarkers of SIRS and MODS associated with canine babesiosis. Res. Vet. Sci. 2016, 105, 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almela, R.M.; Rubio, C.P.; Cerón, J.J.; Ansón, A.; Tichy, A.; Mayer, U. Selected serum oxidative stress biomarkers in dogs with non-food-induced and food-induced atopic dermatitis. Vet. Dermatol. 2018, 29, 229–e82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulka, M.; Garncarz, M.; Parzeniecka-Jaworska, M.; Kluciński, W. Serum paraoxonase 1 activity and lipid metabolism parameter changes in Dachshunds with chronic mitral valve disease. Assessment of its diagnostic usefulness. Pol. J. Vet. Sci. 2017, 20, 723–729. [Google Scholar]

- Rubio, C.P.; Martínez-Subiela, S.; Hernández-Ruiz, J.; Tvarijonaviciute, A.; Cerón, J.J.; Allenspach, K. Serum biomarkers of oxidative stress in dogs with idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease. Vet. J. 2017, 221, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggerone, B.; Scavone, D.; Troìa, R.; Giunti, M.; Dondi, F.; Paltrinieri, S. Comparison of protein carbonyl (PCO), paraoxonase-1 (PON1) and C-reactive protein (CRP) as diagnostic and prognostic markers of septic inflammation in dogs. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrente, C.; Manzanilla, E.G.; Bosch, L.; Villaverde, C.; Pastor, J.; de Gopegui, R.R.; Tvarijonaviciute, A. The diagnostic and prognostic value of paraoxonase-1 and butyrylcholinesterase activities compared with acute-phase proteins in septic dogs and stratified by the acute patient physiologic and laboratory evaluation score. Vet. Clin. Pathol. 2019, 48, 740–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo-Marin, L.; Ceron, J.J.; Tecles, F.; Baneth, G.; Martínez-Subiela, S. Comparison of acute phase proteins in different clinical classification systems for canine leishmaniosis. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2020, 219, 109958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, A.; Veronesi, M.C.; Rossi, G.; Pezzia, F.; Probo, M.; Giori, L.; Paltrinieri, S. Serum paraoxonase-1 activity in neonatal calves: Age related variations and comparison between healthy and sick animals. Vet. J. 2013, 197, 499–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, G.; Ibba, F.; Meazzi, S.; Giordano, A.; Paltrinieri, S. Paraoxonase activity as a tool for clinical monitoring of dogs treated for canine leishmaniasis. Vet. J. 2014, 199, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruggerone, B.; Bonelli, F.; Nocera, I.; Paltrinieri, S.; Giordano, A.; Sgorbini, M. Validation of a paraoxon-based method for measurement of paraoxonase (PON-1) activity and establishment of RIs in horses. Vet. Clin. Pathol. 2018, 47, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardner, I.A.; Greiner, M. Receiver-operating characteristic curves and likelihood ratios: Improvements over traditional methods for the evaluation and application of veterinary clinical pathology tests. Vet. Clin. Pathol. 2006, 35, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, R.W.; Leviev, I.; Ruiz, J.; Passa, P.; Froguel, P.; Garin, M.C. Promoter polymorphism T(-107)C of the paraoxonase PON1 gene is a risk factor for coronary heart disease in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes 2000, 49, 1390–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Motta, S.; Letellier, C.; Ropert, M.; Motta, C.; Thiébault, J.J. Protecting effect of vitamin E supplementation on submaximal exercise-induced oxidative stress in sedentary dogs as assessed by erythrocyte membrane fluidity and paraoxonase-1 activity. Vet. J. 2009, 181, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojic, S.; Kotur-Stevuljevic, J.; Kalezic, N.; Jelic-Ivanovic, Z.; Stefanovic, A.; Palibrk, I.; Memon, L.; Kalaba, Z.; Stojanovic, M.; Simic-Ogrizovic, S. Low paraoxonase 1 activity predicts mortality in surgical patients with sepsis. Dis. Markers 2014, 2014, 427378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulka, M. A review of paraoxonase 1 properties and diagnostic applications. Pol. J. Vet. Sci. 2016, 19, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feingold, K.R.; Memon, R.A.; Moser, A.H.; Grunfeld, C. Paraoxonase activity in the serum and hepatic mRNA levels decrease during the acute phase response. Atherosclerosis 1998, 139, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsillach, J.; Aragonès, G.; Mackness, B.; Mackness, M.; Rull, A.; Beltrán-Debón, R.; Pedro-Botet, J.; Alonso-Villaverde, C.; Joven, J.; Camps, J. Decreased paraoxonase-1 activity is associated with alterations of high-density lipoprotein particles in chronic liver impairment. Lipids Health Dis. 2010, 9, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsillach, J.; Camps, J.; Ferré, N.; Beltran, R.; Rull, A.; Mackness, B.; Mackness, M.; Joven, J. Paraoxonase-1 is related to inflammation, fibrosis and PPAR delta in experimental liver disease. BMC Gastroenterol. 2009, 9, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karsen, H.; Binici, I.; Sunnetcioglu, M.; Baran, A.I.; Ceylan, M.R.; Selek, S.; Celik, H. Association of paraoxonase activity and atherosclerosis in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Afr. Health Sci. 2012, 12, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meazzi, S.; Bristi, S.Z.T.; Bianchini, V.; Scarpa, P.; Giordano, A. Exploring the relationship between canine paraoxonase-1 (PON-1) serum activity and liver disease classified by clinico-pathological evaluation. Animals 2024, 14, 2886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Zhai, R.; Li, H.; Mei, X.; Qiu, G. Prognostic value of serum paraoxonase and arylesterase activity in patients with sepsis. J. Int. Med. Res. 2013, 41, 681–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atay, A.E.; Kaplan, M.A.; Evliyaoglu, O.; Ekin, N.; Isıkdogan, A. The predictive role of Paraoxonase 1 (PON1) activity on survival in patients with metastatic and nonmetastatic gastric cancer. Clin. Ter. 2014, 165, e1–e5. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, K.; Wang, Q.; Ma, Y.; Liu, X. The Antioxidant Enzyme PON1: A Potential Prognostic Predictor of Acute Ischemic Stroke. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 6677111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggerone, B.; Paltrinieri, S.; Giordano, A.; Scavone, D.; Nocera, I.; Rinnovati, R.; Spadari, A.; Scacco, L.; Pratelli, P.; Sgorbini, M. Paraoxonase-1 activity evaluation as a diagnostic and prognostic marker in horses and foals. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2020, 34, 949–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldonza, M.B.D.; Son, Y.S.; Sung, H.J.; Ahn, J.M.; Choi, Y.J.; Kim, Y.I.; Cho, S.; Cho, J.Y. Paraoxonase-1 (PON1) induces metastatic potential and apoptosis escape via its antioxidative function in lung cancer cells. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 42817–42835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginoudis, A.; Pardali, D.; Mylonakis, M.E.; Tamvakis, A.; Tvarijonaviciute, A.; Lymperaki, E.; Ceron, J.J.; Polizopoulou, Z. Oxidative status and lipid metabolism analytes in dogs with mast cell tumors: A preliminary study. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecobichon, D.J.; Stephens, D.S. Perinatal development of human blood esterases. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 1973, 14, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, R.F.; Hornung, S.; Furlong, C.E.; Anderson, J.; Giblett, E.R.; Motulsky, A.G. Plasma paraoxonase polymorphism: A new enzyme assay, population, family, biochemical, and linkage studies. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1983, 35, 393–408. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, T.B.; Jampsa, R.L.; Walter, B.J.; Arndt, T.L.; Richter, R.J.; Shih, D.M.; Tward, A.; Lusis, A.J.; Jack, R.M.; Costa, L.G.; et al. Expression of human paraoxonase (PON1) during development. Pharmacogenetics 2003, 13, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Breed | n |

|---|---|

| Mixed breed | 109 |

| Labrador Retriever | 20 |

| French Bouledogue | 18 |

| Poodle | 16 |

| Golden Retriever | 15 |

| German Shepherd, Jack Russell Terrier | 13 |

| Bernese Mountain Dog | 11 |

| Boxer, NR | 10 |

| Cocker Spaniel, Dachshund | 9 |

| Rottweiler | 8 |

| Dobermann, Maltese, Weimaraner | 7 |

| Chihuahua, CKCS | 6 |

| Maremmano-abruzzese Sheepdog, Staffordshire American Terrier | 5 |

| Border Collie, Dogo Argentino, Epagneul Breton, Fox terrier, German Shorthaired Pointer, Pit bull, Shih Tzu, WHWT | 4 |

| Akita Inu, Beagle, Bracco Italiano, English Setter, Pug, Siberian Husky, Yorkshire Terrier | 3 |

| Australian Shepherd, Belgian Shepherd, Bolognese, Boston Terrier, Bull Terrier, Dalmatian, English Bulldog, Greyhound, Miniature Poodle, Rhodesian Ridgeback, Whippet | 2 |

| Afghan Hound, American Bulldog, Bobtail, Caucasian Shepherd, Cane Corso, Czechoslovakian Wolfdog, Dogue de Bordeaux, Entlebucher Mountain Dog, Flat Coated Retriever, Foxhound, German Wirehaired Pointer, Italian Greyhound, Italian Hound, Leonberger, Newfoundland, Pinscher, Pointer, Samoyed, Shar Pei, Shetland Sheepdog, Schnauzer, Spitz, Springer Spaniel | 1 |

| Ward | Type of Disease/Procedure |

|---|---|

| Cardiology (n = 55) | MVD [n = 28: mild (ACVIM B1) (n = 11), moderate (ACVIM B2) (n = 2), severe (ACVIM C) (n = 11), or associated with other valvular dysfunctions or conditions such as neoplasia (n = 1), CKD (n = 1) edema (n = 3)]; control [n = 15: breed screening (n = 8), wellness visits (n = 7)]; miscellaneous [n = 9: pulmonary hypertension, PDA, atrial rupture, cardiac murmur, pulmonary stenosis, cardiac tumor, ventricular tachycardia, cardiac tamponade, pulmonary thromboembolism (n = 1 each)]; Addison disease [n = 2] |

| Diagnostic imaging (n = 39) | Neoplastic masses [n = 15: carcinoma (n = 4), mast cell tumor (n = 3), splenic masses (n = 2), osteosarcoma (n = 2), meningioma, abdominal mass not further investigated, adrenal mass, sarcoma (n = 1 each)]; osteo-muscular symptoms [n = 11: Back pain (n = 6), lameness (n = 4), CMO (n = 1)]; neurological symptoms [n = 5: Chiari-like syndrome (n = 2), discal hernia (n = 2), intracranic mass (n = 1)]; abdominal abnormalities [n = 4: splenomegaly, likely inflammatory origin (2), focal enteropathy (n = 1), ureteral dysplasia (n = 1)]; controls [n = 4: Screening for breed diseases (n = 4)] |

| Emergency/first opinion (n = 93) | Inflammation [n = 29: respiratory symptoms (coughing, discharge, rhinitis, n = 9), cystitis (n = 4), fever responsive to anti-inflammatory treatments (n = 3) pyometra (n = 3), bacteriemia (n = 3), otitis (n = 3), ab ingestis pneumonia (n = 1) cutaneous abscess (n = 1), parvovirus (n = 1), peritonitis (n = 1)]; gastrointestinal signs [n = 20: Vomiting and/or diarrhea with acute clinical presentation]; foreign bodies [n = 11: cutaneous (n = 5), gastrointestinal (n = 4), nasal (n = 2)]; chronic or acute bleeding [n = 5: ulcerated tumors (n = 2), splenic hematoma (n = 1), hemoperitoneum (n = 1), ear wound (n = 1)]; polytrauma [n = 5: car accident (n = 5)]: acute urinary disorders [n = 4: urinary obstruction (n = 3), AKI (n = 1)]; checkup visit [n = 4]; dilatation/volvulus [n = 4: gastric volvulus dilatation (n = 3), intestinal intussusception (n = 1)]; cachexia in neoplastic patients [n = 4: unclassified abdominal tumor (n = 1), lymphoma (n = 1) mast cell tumor (n = 1), carcinoma (n = 1)]; neurological symptoms [n = 3: acute paraplegia (n = 2), convulsions (n = 1)]; rodenticide poisoning [n = 2]; portosystemic shunt [n = 2] |

| Internal medicine (n = 80) | CKD [n = 24]; dermatological signs [n = 10: pruritus and generalized dermatitis (n = 5), interdigital dermatitis (n = 3), nodular pyogranulomatous panniculitis (n = 1) sarcoptic and otodectic mange (n = 1)]; gastrointestinal diseases [n = 8: lymphoplasmocytic gastritis or enteritis (n = 3), hemorrhagic enteritis (n = 2), giardiasis (n = 2), malabsorption (n = 1)]; leishmaniasis [n = 8]; endocrine diseases [n = 6: diabetes mellitus (n = 3), hypothyroidism (n = 2), hyperadrenocorticism (n = 1)]; wellness visit [n = 6]; chronic hepatopathy [n = 4]; immune-mediated polyarthritis [n = 4]; urinary disorders [n = 4: urolithiasis (n = 3) recurrent cystitis (n = 1)]; hematological disorders [n = 3: immune-mediated thrombocytopenia (n = 2), immune-mediated hemolytic anemia (n = 1)]; miscellaneous [n = 3: cataract (n = 1), dirofiraliasis (n = 1), splenic sarcoma (n = 1)] |

| Neurology (n = 17) | idiopathic epilepsy [n = 5]; peripheral neuritis [n = 5]; ataxia [n = 2]; vestibular syndrome [n = 2]; prosencephalic syndrome [n = 1]; discal hernia [n = 1]; paraplegia [n = 1] |

| Obstetric/ reproduction (n = 25) | castration [n = 7]; gynecological checkup [n = 5]; pregnancy monitoring [n = 4]; mammary neoplasm [n = 3]; cystic endometrial hyperplasia [n = 2]; ovariectomy [n = 2]; congenital abnormality [n = 1]; dystocia [n = 1] |

| Oncology (n = 84) | mast cell tumor [n = 22]; carcinoma [n = 20]; lymphoma [n = 17]; sarcoma [n = 11: soft tissue sarcoma (n = 6); perivascular wall tumor (n = 3); hemangiosarcoma (n = 1), histiocytic sarcoma (n = 1)]; miscellaneous [n = 6: thymoma, tricoblastoma, intraarticular tumor, leiomyosarcoma, sertolioma, retromandibular tumor (n = 1 each)]; hepatic tumor [n = 3]; melanoma [n = 3]; plasma cell tumor [n = 2] |

| Surgery (n = 42) | orthopedic [n = 12]; neoplasia [n = 11]; BOAS [n = 4]; dental surgery [n = 3]; chronic otitis [n = 3]; miscellaneous [n = 3: bronchocscopy (n = 1), syalocele (n = 1), urethral surgery (n = 1)] perineal hernia [n = 2]; laryngeal surgery [n = 2]; nasal surgery [n = 2]; |

| Ward | n | PON-1 (U/mL) | Low PON-1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiology (CA) | 55 | 199.9 ± 56.8 (202.4) **EF 165.2–237.0 (74.3–346.0) | 4 (7.3%) |

| Diagnostic Imaging (DI) | 39 | 192.4 ± 51.4 (189.3) *EF 155.6–232.7 (47.2–292.0) | 2 (5.1%) |

| Emergency/first opinion (EF) | 93 | 166.3 ± 58.3 (170.3) ***OR,SU; **CA,NE,ON; *DI,IM 131.1–205.3 (32.8–315.0) | 17 (18.3%) |

| Internal medicine (IM) | 80 | 185.5 ± 61.3 (184.0) *SU,EF 144.8–225.3 (18.5–351.0) | 7 (8.8%) |

| Neurology (NE) | 17 | 211.1 ± 52.7 (228.3) **EF 152.8–247.0 (130.0–287.4) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Obstetric/reproduction (OR) | 25 | 205.0 ± 32.8 (202.0) ***EF 179.3–229.9 (136.0–262.0) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Oncology (ON) | 84 | 191.5 ± 52.4 (189.6) **EF 156.5–223.6 (66.2–314.0) | 5 (6.0%) |

| Surgery (SU) | 42 | 203.4 ± 39.6 (203.0) ***EF; *IM 183.6–234.2 (80.7–290.0) | 2 (4.8%) |

| p = 0.002 | p = 0.015 |

| Outcome | T0 | T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | T5 | T6 | T7 | T8 | T9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discharge | 311.0 | 219.0 | ||||||||

| Discharge | 323.0 | 249.0 | ||||||||

| Discharge | 273.0 | 293.0 | ||||||||

| Death | 258.0 | 181.0 | 225.0 | 237.0 | 149.2 | |||||

| Discharge | 117.0 | 124.0 | 180.0 | 199.0 | 186.0 | |||||

| Discharge | 187.0 | 125.0 | ||||||||

| Death | 184.0 | 107.0 | ||||||||

| Discharge | 108.0 | 184.0 | 120.0 | 198.0 | ||||||

| Death | 155.0 | 142.0 | ||||||||

| Discharge | 134.0 | 95.3 | 81.6 | 88.6 | 103.0 | 101.0 | 166.0 | 124.0 | 197.0 | 196.0 |

| Discharge | 91.8 | 94.9 | 106.0 | 110.0 | 183.0 | 228.0 | 211.0 | |||

| Euthanasia | 283.0 | 198.0 | 220.0 | |||||||

| Euthanasia | 173.0 | 119.0 | 149.0 | 127.0 | ||||||

| Discharge | 45.7 | 23.8 | ||||||||

| Discharge | 96.7 | 87.2 | 80.7 | |||||||

| Discharge | 153.0 | 116.0 | ||||||||

| Discharge | 95.7 | 177 | ||||||||

| Discharge | 115.9 | 163.1 | 162 | |||||||

| Euthanasia | 138 | 118.1 | ||||||||

| Discharge | 93.8 | 103.5 | ||||||||

| Discharge | 260 | 209 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bettoni, V.; Tagliasacchi, F.; Scavone, D.; Galizzi, A.; Locatelli, C.; Amati, M.; Ferrari, R.; Scarpa, P.; Paltrinieri, S. Serum Paraoxonase-1 (PON-1) in Dogs: Frequency of Decreased Values in Clinical Practice and Prognostic Significance. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 1066. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci12111066

Bettoni V, Tagliasacchi F, Scavone D, Galizzi A, Locatelli C, Amati M, Ferrari R, Scarpa P, Paltrinieri S. Serum Paraoxonase-1 (PON-1) in Dogs: Frequency of Decreased Values in Clinical Practice and Prognostic Significance. Veterinary Sciences. 2025; 12(11):1066. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci12111066

Chicago/Turabian StyleBettoni, Virginia, Filippo Tagliasacchi, Donatella Scavone, Alberto Galizzi, Chiara Locatelli, Maria Amati, Roberta Ferrari, Paola Scarpa, and Saverio Paltrinieri. 2025. "Serum Paraoxonase-1 (PON-1) in Dogs: Frequency of Decreased Values in Clinical Practice and Prognostic Significance" Veterinary Sciences 12, no. 11: 1066. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci12111066

APA StyleBettoni, V., Tagliasacchi, F., Scavone, D., Galizzi, A., Locatelli, C., Amati, M., Ferrari, R., Scarpa, P., & Paltrinieri, S. (2025). Serum Paraoxonase-1 (PON-1) in Dogs: Frequency of Decreased Values in Clinical Practice and Prognostic Significance. Veterinary Sciences, 12(11), 1066. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci12111066