Clinical Reasoning About Timely Euthanasia of Compromised Pigs

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. General Introduction

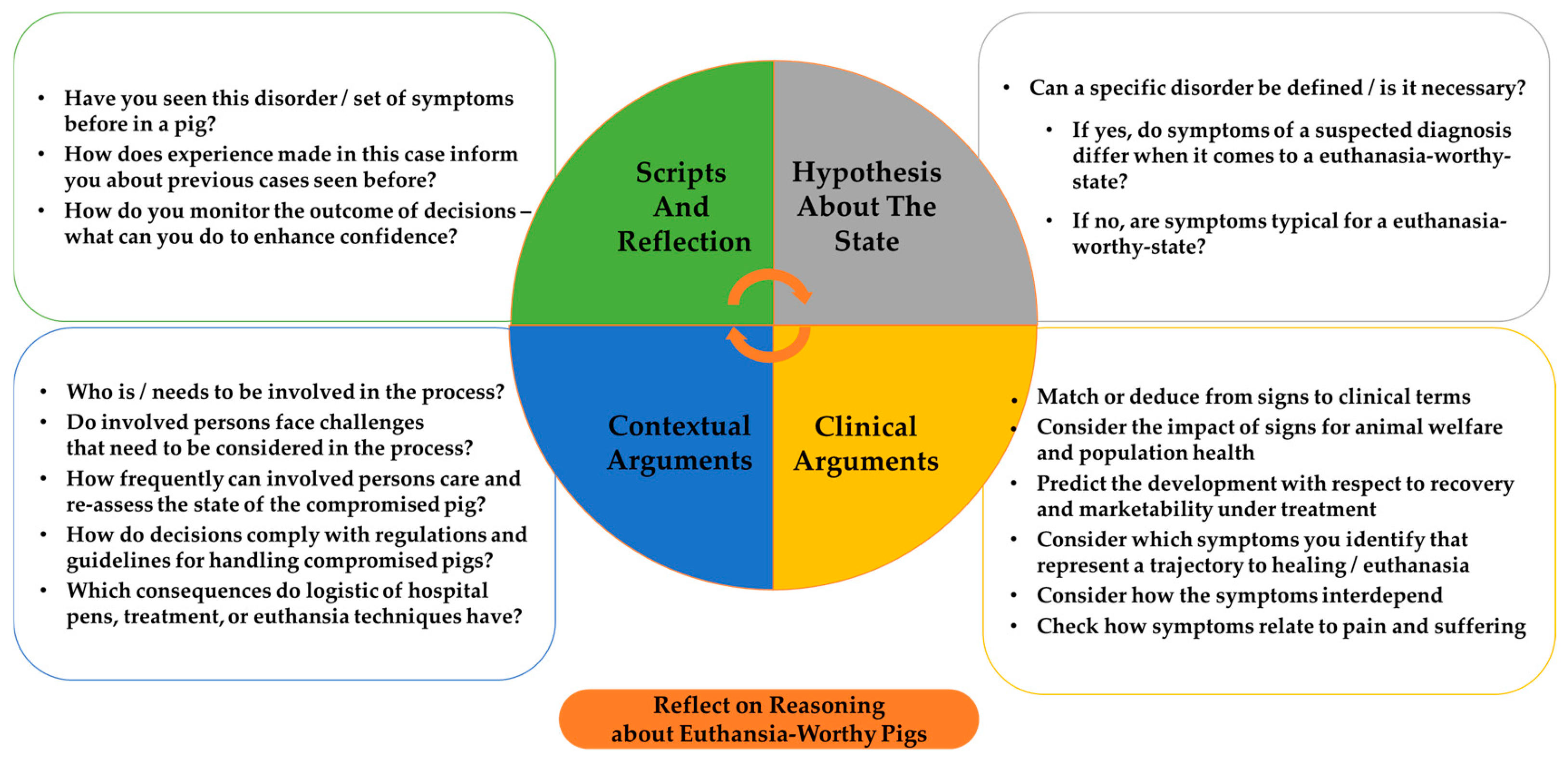

2. Conceptual Background

2.1. Euthanasia of Compromised Pigs

2.2. Clinical Reasoning

2.2.1. Assessing Clinical Reasoning

2.2.2. Logics of Thought in Clinical Reasoning

2.2.3. Scripts in Clinical Reasoning

2.2.4. Euthanasia in Clinical Reasoning

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

4.1. Steps in the Process

4.1.1. Step 1: Identification of Animals

4.1.2. Step 2: Gathering Information/Data Collection

4.1.3. Step 3: Analyzing and Interpreting Data

4.1.4. Step 4: Mutual Goals

4.1.5. Step 5: Taking Decisions

4.1.6. Step 6: Evaluate the Outcome

4.1.7. Step 7: Reflect on the Process

4.2. Reasoning and Learning During the Process

4.2.1. Intuitive Reasoning

4.2.2. Analytical Reasoning

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- How long have you been working with pigs?

- When did you complete an agricultural vocational qualification (farmer)/since when do you hold a veterinary license (veterinarians)?

- Have you completed any further education?

- What is your position on farm (farmer)/in practice (veterinarians)

- What is the average size of the herds on the farm that you care for?

- Is “euthanasia of compromised pigs” a topic that is of general concern for you?

- Is there anything about euthanasia of compromised pigs that has attracted particular attention among your colleagues?

- For farmers only:

- ◦

- Is it one of your tasks to decide about euthanasia of a pig?

- ◦

- Which technique do you use for euthanasia?

- When was the last time you euthanized a compromised pig?

- For veterinarians only

- ◦

- Who is rather conducting euthanasia—farmers or veterinarians?

- In which cases of diseases or injuries do you often find yourself in a situation where you have to consider euthanasia?

- ◦

- If it is a long list: In which of the mentioned cases do you find it particularly difficult to determine the right time-point for euthanasia?

- ◦

- In addition for veterinarians: Are these cases particularly difficult for farmers, too?

- For each disorder/injury X asked repeatedly:

- ◦

- What of this pig attracts your attention on day one? Or: in which state is a pig presented to you the first time?

- ◦

- How do you determine for a pig with X whether the state of a pig is improving/develops to recovery?

- ◦

- How do you elaborate for a pig with X whether the state of a pig is worsening/develops to euthanasia?

- ▪

- Answer to requests about the meaning of “elaborating”: what comes into mind as considerations and observations

- How do you identify that a pig feels pain?

- How do you identify that a pig is suffering?

- What kind of information or topics would have to be addressed in a guideline to improve the situation

- Is there anything left that you want to talk about, any question or issue left open?

References

- Campler, M.R.; Pairis-Garcia, M.D.; Rault, J.-L.; Coleman, G.; Arruda, A.G. Caretaker attitudes toward swine euthanasia. Transl. Anim. Sci. 2018, 2, 254–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoffregen, J.; Winkelmann, T.; Schneider, B.; Gerdes, K.; Miller, M.; Reinmold, J.; Kleinsorgen, C.; Toelle, K.H.; Kreienbrock, L.; grosse Beilage, E. Landscape review about the decision to euthanize a compromised pig. Porc. Health Manag. 2024, 10, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxmose Nielsen, S.; Alvarez, J.; Bicout, D.J.; Calistri, P.; Depner, K.; Drewe, J.A.; Garin-Bastuji, B.; Gonzales Rojas, J.L.; Gortázar Schmidt, C.; Michel, V. Welfare of pigs during killing for purposes other than slaughter. EFSA J. Eur. Food Saf. Auth. 2020, 18, e06195. [Google Scholar]

- grosse Beilage, E.; Hennig-Pauka, I.; Kemper, N.; Kreienbrock, L.; Kunzmann, P.; Tölle, K.-H.; Waldmann, K.-H.; Wendt, M. Abschlussbericht: Sofortmaßnahmen zur Vermeidung Länger Anhaltender Erheblicher Schmerzen und Leiden bei Schwer Erkrankten/Verletzten Schweinen durch Rechtzeitige Tötung; DVG Service: Gießen, Germany, 2021; ISBN 978-3-86345-609-2. [Google Scholar]

- Stoffregen, J.; Winkelmann, T.; Schneider, B.; Fehrmann, M.; Gerdes, K.; Miller, M.; Reinmold, J.; Hennig-Pauka, I.; Kemper, N.; Kleinsorgen, C.; et al. Influences on the decision to euthanize a compromised pig. Animals 2024, 14, 2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rault, J.-L.; Holyoake, T.; Coleman, G. Stockperson attitudes toward pig euthanasia. J. Anim. Sci. 2017, 95, 949–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullins, C.R.; Pairis-Garcia, M.D.; George, K.A.; Anthony, R.; Johnson, A.K.; Coleman, G.J.; Rault, J.L.; Millman, S.T. Determination of swine euthanasia criteria and analysis of barriers to euthanasia in the United States using expert opinion. Anim. Welf. 2017, 26, 449–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullins, C.R.; Pairis-Garcia, M.D.; Campler, M.R.; Anthony, R.; Johnson, A.K.; Coleman, G.J.; Rault, J.L. Teaching tip: The development of an interactive computer-based training program for timely and humane on-farm pig euthanasia. J. Vet. Med. Educ. 2018, 45, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campler, M.R.; Pairis-Garcia, M.D.; Rault, J.-L.; Coleman, G.; Arruda, A.G. Interactive euthanasia training program for swine caretakers; a study on program implementation and perceived caretaker knowledge. J. Swine Health Prod. 2020, 28, 258–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agne, G.F.; Carr, A.M.N.; Kirkwood, R.N.; Petrovski, K.R. Assisting the Learning of Clinical Reasoning by Veterinary Medical Learners with a Case Example. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 433. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, A.N.; Ferlini Agne, G.; Kirkwood, R.N.; Petrovski, K.R. Teaching clinical reasoning to veterinary medical learners with a case example. Encyclopedia 2024, 4, 753–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, B. Clinical reasoning: Concept analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2010, 66, 1151–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, H.G.; Norman, G.R.; Boshuizen, H.P. A cognitive perspective on medical expertise: Theory and implication [published erratum appears in Acad Med 1992 Apr; 67 (4): 287]. Acad. Med. 1990, 65, 611–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charlin, B.; Boshuizen, H.P.A.; Custers, E.J.; Feltovich, P.J. Scripts and clinical reasoning. Med. Educ. 2007, 41, 1178–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elstein, A.S. Thinking about diagnostic thinking: A 30-year perspective. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. 2009, 14, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levett-Jones, T.; Hoffman, K.; Dempsey, J.; Jeong, S.Y.-S.; Noble, D.; Norton, C.A.; Roche, J.; Hickey, N. The ‘five rights’ of clinical reasoning: An educational model to enhance nursing students’ ability to identify and manage clinically ‘at risk’ patients. Nurse Educ. Today 2010, 30, 515–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Council, (EC). CR. No 1099/2009, of 24 September 2009, on the Protection of Animals at the Time of Killing, (14 December 2015); European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Custers, E.J.F.M. Thirty years of illness scripts: Theoretical origins and practical applications. Med. Teach. 2015, 37, 457–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, A.; Elstein, A.S. Clinical reasoning in medicine. In Clinical Reasoning in the Health Professions; Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2008; pp. 223–234. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, K. A Comparison of Decision-Making by “Expert” and “Novice” Nurses in the Clinical Setting, Monitoring Patient Haemodynamic Status Post Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Surgery. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Technology Sydney, Sydney, Australia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez, A. Differential Diagnosis of Diseases. In Diseases of Swine; Zimmerman, J., Karriker, L., Ramirez, A., Schwartz, K., Stevenson, G., Zhang, J., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 59–74. [Google Scholar]

- Feltovich, P.J.; Barrows, H.S. Issues of generality in medical problem solving. In Tutorials in Problem-Based Learning; Van Gorcum: Assen, The Netherlands, 1984; pp. 128–142. [Google Scholar]

- Mayring, P. Qualitative Content Analysis: Theoretical Foundation, Basic Procedures and Software Solution; SSOAR: Klagenfurt, Austria, 2014; Available online: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-395173 (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Arocha, J.F.; Patel, V.L. Methods in the Study of Clinical Reasoning. In Clinical Reasoning in the Health Professions; Higgs, J., Jones, M., Loftus, S., Christensen, N., Eds.; Elsevier Health Sciences: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2008; pp. 193–204. Available online: https://i.clinref.com/data/uploads/books/Clinical-reasoning-in-the-health-professions.pdf#page=208 (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Plano Clark, V.L. Meaningful integration within mixed methods studies: Identifying why, what, when, and how. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2019, 57, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younas, A.; Fàbregues, S.; Creswell, J.W. Generating metainferences in mixed methods research: A worked example in convergent mixed methods designs. Methodol. Innov. 2023, 16, 276–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gephi.org. Gephi Features 2025. Available online: https://gephi.org/features/ (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Jacomy, M.; Jokubauskaitė, E. Unblackboxing Gephi: How a User Culture Shapes Its Scientific Instrument. Ouvrir la Boîte Noire de Gephi: Comment un Instrument Scientifique est Façonné par la Culture de ses Utilisateurs; HAL Id:hal-03729114; HAL: Lyon, France, 2022; Available online: https://hal.science/hal-03729114v1 (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Jacomy, M.; Venturini, T.; Heymann, S.; Bastian, M. ForceAtlas2, a continuous graph layout algorithm for handy network visualization designed for the Gephi software. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e98679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Activity | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Problem representation | Summarize gathered facts into a concise problem representation as a basis for differential hypotheses/diagnoses, use medical terms |

| Review context | Consider gathered facts regarding the examination of the environment |

| Problem identification | Synthesize facts and inferences to make a definitive diagnosis of the patient’s problem |

| Recall knowledge | Be aware of/recall previous exemplars, illness scripts, prototypes and used semantic qualifiers |

| Interpretation | Understand symptoms and cues of the case |

| Discrimination | Distinguish relevant from irrelevant information, define missing cues |

| Relating | Define patterns and clusters |

| Inferring | Make deductions or logical flows from considerations |

| Matching | Match findings with previous situations |

| Predicting | Predict an outcome |

| Activity | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Self-analysis | A person reflects on whether the performance led to reach goals for the encounter |

| Self-awareness | Handling criticism and/or recognizing own limits |

| Self-confidence | Speak in awkward situations |

| Self-efficacy | Dedicate extra time to self-reflect and enhance ongoing and future encounters |

| Self-evaluation | Check if a decision needs to be adjusted |

| Self-regulation | Control the behavior/expressions of the affective state |

| No. | Step | Activities (Subordinate Steps of Consideration) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Identify the patient | A Early Identification |

| 2 | Gathering data | A Specific actions |

| B Relevant outcomes B1: Patient data B2: General examination goals B3: Abnormal symptoms | ||

| C Patient circumstances | ||

| 3 | Analyzing data and interpreting steps | A Suspected hypotheses (diagnoses or hypothesis about the state of health) A1: Disorder/diagnosis vs. euthanasia-worthy states A2: Specificity of hypotheses |

| B Clinical arguments for a hypothesis B1: Matching B2: Inferring B3: Relating B4: Predicting B5: Discriminating | ||

| C Contextual arguments for a hypothesis C1: Characteristics of involved persons C2: Institutional structures C3: Farm and local equipment C4: “Individual case” theme | ||

| D Recalled scripts D1: Specific illness scripts D2: Semantic qualifiers | ||

| 4 | Establish mutual goals | A Population health consequence |

| B Farmer–veterinarian consultation and communication | ||

| 5 | Taking actions | A Other actions than euthanasia |

| B Role of caring for pigs | ||

| 6 | Evaluate the outcome | A Development of clinical signs |

| B Role of uncertainty | ||

| 7 | Reflect on the process | A Self-regulation |

| B Self-evaluation/monitoring | ||

| C Self-awareness | ||

| D Self-confidence | ||

| E Self-esteem | ||

| F Self-efficacy | ||

| G Self-analysis |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kschonek, J.; Winkelmann, T.; Kreienbrock, L.; grosse Beilage, E. Clinical Reasoning About Timely Euthanasia of Compromised Pigs. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 943. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci12100943

Kschonek J, Winkelmann T, Kreienbrock L, grosse Beilage E. Clinical Reasoning About Timely Euthanasia of Compromised Pigs. Veterinary Sciences. 2025; 12(10):943. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci12100943

Chicago/Turabian StyleKschonek, Julia, Tristan Winkelmann, Lothar Kreienbrock, and Elisabeth grosse Beilage. 2025. "Clinical Reasoning About Timely Euthanasia of Compromised Pigs" Veterinary Sciences 12, no. 10: 943. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci12100943

APA StyleKschonek, J., Winkelmann, T., Kreienbrock, L., & grosse Beilage, E. (2025). Clinical Reasoning About Timely Euthanasia of Compromised Pigs. Veterinary Sciences, 12(10), 943. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci12100943