Abstract

Plant-based beverages are a viable alternative for elderly consumers because of their practicality and sustainable appeal. The use of Brazil nuts for these beverages is relevant because of the added value given to the country’s agrobiodiversity and the nuts’ nutritional quality, including their high selenium content. This study aimed for the understanding and acceptance by elderly people of a vegetable beverage made from Brazil nuts and fruit. The investigation was divided into two parts: (1) development and sensory analysis of Brazil nut beverages, and (2) consumers’ perception, choice, and influencing factors for these beverages. In the first stage, four beverages were formulated with different fruit pulps. A total of 100 elderly individuals (>60 years; 69% female) evaluated the sensory acceptance and purchase intention of the beverages. In the second stage, an online questionnaire was applied to 220 elderly individuals (>60 years-old; 52.7% female), which consisted of a choice test of nut beverage packages, a food neophobia scale, and questions about vegetable beverage consumption. The study showed that the selenium claim was one of the most relevant factors in the choice, demonstrating that using Brazil nuts can boost beverage purchases. Further tests are still needed to improve the attributes, such as sweet taste and appearance. Despite this, the blend of Brazil nuts with fruits positively influenced the choice and acceptance of these products by elderly individuals.

1. Introduction

Aging is a natural biological process that leads to the alteration and decline of some physiological functions of the human body [1]. Older adults develop special nutritional needs as the years go by because the senescence process can generate specific demands due to the natural impairment of nutrient absorption, use, and excretion [2]. In addition to physiological impairment, the low intake of these nutrients can also affect the metabolism and health of these individuals because the elderly population, in general, tends to have lower consumption of healthy calories and less food variability [3].

According to the World Health Organization, people aged 60 and over are considered elderly [4]. In Brazil, the elderly population is constantly growing. In the last ten years, this group has risen from 11.3% to 14.7% of the total population, while the younger population (0–29 years) has shrunk from 49.9% to 43.9% [5], making the elderly an increasingly relevant group that deserves the attention of the food industry to develop suitable products for this niche to guarantee a better quality of nutrition and life.

In the context of an aging population, developing products that meet the specific needs of the elderly while at the same time satisfying their sensory and hedonic expectations is a great challenge for the food industry and also for society [6]. In this sense, food fortification is a common management approach for older people with reduced appetite who need to take in adequate nutrients. In this regard, food producers have been making efforts in recent years to improve food offerings targeted at the elderly, particularly texture-modified and fortified foods [7,8,9].

Several studies have described the development of fortified products for the elderly as a tool for preventing disease and maintaining health. Fortified products such as yogurts [10,11], and beverages [12,13] are commonly mentioned in the literature. In general, the enrichment of foods for the elderly aims to increase the levels of proteins, probiotics, and micronutrients [14,15,16].

Plant-based beverages can therefore be an alternative for these consumers, since they are nutritious, practical, and often have sustainable appeal [17,18,19]. Functional beverages, especially those made from plants, have gained traction as consumers seek foods that improve their health [20]. A recent review [21] also highlighted that plant-based beverages can have health-promoting properties (mainly due to the bioactive compounds that come from plant extracts and fruit juices, for example) and that in vivo studies and clinical trials with these beverages indicate antidiabetic and hypolipidemic effects. These findings are important to consider when developing these beverages for the elderly, since diseases such as diabetes and hypertension are common at this stage of life. Data from the Brazilian Ministry of Health based on its Health Surveillance Survey [22] show that in 2023, more than 50% of individuals between 55 and 64 years of age and 65% of individuals aged 65 or over were hypertensive; while for diabetes, these percentages were 22.4% and 30.3%, respectively.

However, developing functional beverages for the elderly can pose some challenges, which according to [23] include the following: meeting specific dietary needs to counteract problems such as chronic non-communicable diseases; developing products with health benefits, to supplement diets or prevent diseases and to reduce healthcare costs; formulating foods with appropriate texture and consistency; creating packaging that facilitates the visualization of the product and the reading of information; providing clear and truthful information to minimize difficulties of understanding such products to inhibit the use of false health claims; and offering an affordable price.

In this sense, Brazil nuts are attractive because besides coming from Brazilian agrobiodiversity, and have high nutritional value, especially high selenium content [24], a mineral of fundamental importance for the proper functioning of cells, in addition to having antioxidant action, playing a role in the conversion of thyroid hormones, and strengthening of immunity [25].

An important strategy to help the elderly choose products is providing easily accessible information on the label. This can be a strategy for new product development, which faces the obstacle of consumers’ reluctance to try new products, a concept called food neophobia. This is a major challenge to reaching resistant audiences, especially the elderly and children [26,27,28,29]. The study by [30] evaluated 141 elderly Brazilians and reported that 72.3% had the habit of reading food labels and observing the product’s expiration date as well as the fat and sodium content. The review by [31] highlighted that factors such as price and health claims were important in the choice of products by elderly people.

In this sense, it is necessary to improve and develop products that meet the needs of this population while mitigating their limitations. Therefore, the objective of this study was to develop Brazil nut beverages, with or without the addition of fruits, to evaluate the nutritional, microbiological, and sensory quality of these products by elderly consumers, in addition to understanding the perception and effect of packaging factors (flavor, claims and price) on the choice of nut beverages by the elderly population.

2. Materials and Methods

This study was divided into two parts. The first part consisted of the development of Brazil nut vegetable beverage formulations, with and without the addition of fruit pulp. In addition, the formulations were analyzed for their nutritional composition and microbiological profiles. A sensory analysis of the global acceptance and purchase intention of elderly people regarding these beverages concluded the first part of the study. The second part consisted of an online questionnaire that evaluated the perception and purchase of nut beverages by elderly consumers, considering factors such as taste, claims, and price.

2.1. Part 1: Brazil Nut Vegetable Beverage Development, Nutritional Composition, Microbiological and Sensory Analysis

2.1.1. Acquisition of Food Supplies

The Brazil nut kernels were obtained from a sustainable extraction cooperative in Brazil’s Amazon region. They were stored and transported in sanitized containers at refrigeration temperature (8 °C ± 1 °C). Before preparing the beverages, these nuts were cleaned and sanitized with a 0.7 ppm sodium hypochlorite solution.

The pasteurized and frozen fruit pulps were obtained from local markets made from the same batch and date of manufacture. The fruits consisted of cashew apples (Anacardium occidentale), açaí berries (Euterpe oleracea), and strawberries (Fragaria ananassa).

2.1.2. Elaboration of Beverages

The beverages were formulated with 10 g of Brazil nuts blended in 200 mL of mineral water (Minalba®, Campos do Jordão, Brazil), 0.3 mL of sucralose, and 20 g of fruit pulp (except for the CA formulation, which was composed only of water and Brazil nuts). These ingredients were mixed in a household blender. The respective quantities were determined in a pre-test and the flavors were chosen based on a previous study involving consumer preferences for blends [32]. Four samples of beverages were produced: strawberry (MR), açaí (AI), cashew apple (JU), and only Brazilian nut (CA). Tests were also carried out on the addition of liquid lecithin to improve the emulsification of the beverages, using concentrations of 0.2%, 0.5%, and 1%, but these were not considered as they demonstrated insignificant results.

After previous tests, the beverages were pasteurized at 95 °C for 5 min and then refrigerated and stored at a temperature of 5 °C ± 1 °C.

2.1.3. Centesimal Composition and Microbiological Evaluation

Centesimal composition analyses were carried out in triplicate according to the method of the Association of Official Analytical Chemists [33]. The carbohydrate content was calculated as the difference between 100% and the sum of the percentages of moisture, protein, total lipids, and ash. The energy value was determined from the protein, lipid, and carbohydrate contents multiplied by the Atwater factors, which were 4 kcal/g, 9 kcal/g, and 4 kcal/g, respectively.

Microbiological analyses were performed for the total count of aerobic mesophilic bacteria, for the mold and yeast count, and for Salmonella sp., Bacillus cereus, and Enterobacteriaceae, according to the Compendium of Methods for the Microbiological Examination of Foods [34]. Aflatoxin analyses were carried out on Brazil nut kernels, and AFB1, AFB2, AFG1, and AFG2 were determined by HPLC-FD/KobraCell® [35,36].

The quantification of minerals was determined by inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) (Optima 2100DV, PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) after complete digestion of the sample in nitric and perchloric acids, following the AOAC Methods 975.03 and 990.08, with measurements collected in triplicate.

2.1.4. Consumer Perception of Brazil Nut Beverages (Sensory Analysis)

Participants of the Sensory Analysis

A total of 100 participants of both genders were recruited to take part voluntarily in this stage of the study. All partcipants were residents of the city of Rio de Janeiro/RJ, Brazil. The criteria for participation were a minimum age of 60 years old, good general health, being free from illness, being non-smokers, and not having contracted the COVID-19 virus in the past three months or having symptoms that affect smell and taste. Participants were also informed about the ingredients used in the formulations before the tests and could refuse to participate if they had an allergy, intolerance, or any other factor that limited their consumption of the ingredients presented.

Recruitment and testing were conducted at a social institution for the elderly in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. All participants were residents of Rio de Janeiro and had roughly the same monthly income. On the day of the tests, the individuals were invited through verbal interactions and posters. Those who agreed to participate were taken to a private room where the test was explained and they signed the informed consent form.

Global Acceptance and Purchase Intention

The tests took place in a private room, at individual tables, with a maximum of two participants at a time, to ensure the full assistance and instruction of the participants. Participants tried the four samples monadically (MR, AI, JU, CA). Samples were served in 50 mL white disposable cups containing approximately 30 mL of each sample, refrigerated (8 °C ± 2 °C) and coded with random and balanced three-digit codes. The sample presentation order was balanced according to Williams’ Latin square [37]. Mineral water and a salt cracker were offered to cleanse the palate.

For each sample, participants answered an acceptance test with a 7-point hedonic scale (where 1 = I disliked it very much, and 7 = I liked it very much) [38] and a purchase intention test with a 5-point scale (where 1 = I would certainly not buy it, and 5 = I would certainly buy it). Participants could provide comments if they wished.

2.2. Part 2: Consumer Perception of Brazil Nut Beverages (Online Study)

2.2.1. Participants of Online Study

A nationwide online study was conducted with 220 participants of both genders, with a minimum participation age of 60 years old. The questionnaire was implemented online on the appropriate platform, and recruitment and collection occurred between June 2023 and July 2023. All participants agreed to the consent form.

2.2.2. Experimental Design

For the development of the packaging used in the questionnaire, a fractional factorial design for Choice-Based Conjoint Analysis (CBC) was provided by the XLSTAT software (Addinsoft, New York, NY, USA, v. 2023.1.6) consisting of eight packages and their pairs. For this design, six factors were manipulated: “Price”, “Selenium claim”, “Functional claim”, “Agrobiodiversity claim”, “60+ claim”, and “Flavor” with 2 × 2 × 2 × 2 × 2 levels, respectively (Table 1). Figure 1 depicts the packaging models used in this study.

Table 1.

Factors and levels used in the CBC experimental design.

Figure 1.

Beverage packages designed with the claims for the online questionnaire. The prices were presented to consumers in real (BRL), the official Brazilian currency, and the equivalent in dollars at the exchange rate in effect at the time of the study (high price USD 1.44 and low price USD 0.97).

The “Price” was defined through research before the study, estimating the market values of products in this category. The “Selenium claim” factor was determined based on the estimated selenium content in the nuts in previous analyses according to Brazilian legislation [39]. The “Functional claim” was also used based on studies demonstrating the antioxidant activity of compounds present in Brazil nuts [17,24].

Regarding agrobiodiversity, this claim was made because the Brazil nuts came from a sustainable extraction cooperative. The “60+ claim” factor was used because this product is aimed at the older population. Finally, the “Flavor” factor was defined based on a previous study [32]. A professional graphic designer with experience in food packaging developed the packaging.

2.2.3. Online Questionnaire: Experimental Procedure

The questionnaire was structured in four sections. Section 1 included a food neophobia scale (FNS). In Section 2, a CBC test with eight pairs of packages developed for this study and described in the experimental design was carried out with forced choices among the packages, where participants were asked which beverage they would buy. Section 3 asked participants about their consumption of nut beverages, with the following question: “Do you consume vegetable beverages (non-alcoholic) based on nuts or peanuts?” followed by the alternative answers: “Yes, often”; “Yes, occasionally”; “Yes, rarely”; “I don’t know what nut beverage are”; “I don’t consume them, but I’m interested in trying them”; and “I don’t consume them, and I’m not interested in trying them.” Section 4 collected participants’ socioeconomic data, such as gender, age, geographical region of residence, and economic class.

Food Neophobia Scale (FNS)

The FNS was included in the questionnaire applied, based on the study of [40], translated and validated into Portuguese by [41]. Ten questions (Table 2) about the expectation of new foods were asked, ranked on a Likert scale of 1–7 points (1 = strongly disagree; 4 = neither agree nor disagree; 7 = strongly agree).

Table 2.

Questions asked in the online questionnaire based on the FNS.

2.3. Ethical Considerations

Before being released to the public, the questionnaire was submitted to the Ethics and Research Committee of Federal University of the State of Rio de Janeiro and was approved under CAAE protocol number 57364922.4.0000.5285.

An informed consent form was made available to the participants, and signatures were collected for permission to continue the study. All sensitive data were protected, and respondents were told that only general data would be used for academic purposes.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.4.1. Physicochemical, Microbiological, and Sensory Analysis

Descriptive statistics were performed and the results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for each variable. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post-test was conducted to compare the variables of nutritional composition, microbiological evaluation, global acceptance, and purchase intention among the beverages. Significant values of p < 0.05 were considered in all analyses.

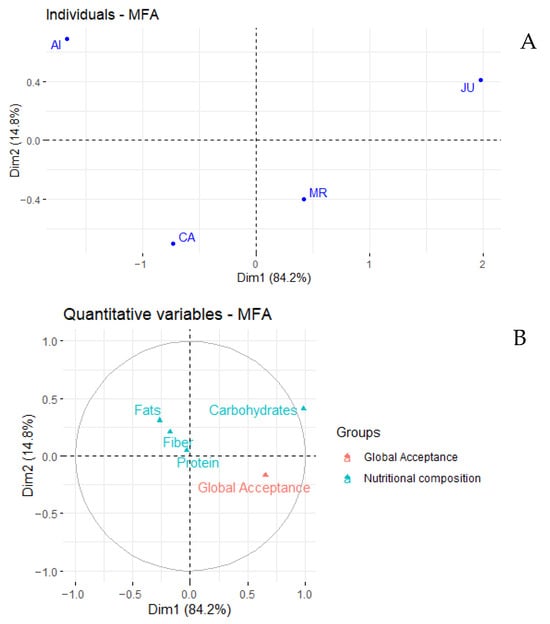

Multiple factor analysis (MFA) was performed using R software version 4.4.3, through the “FactoMineR” and “Factoextra” packages [42,43], to explore the possible relationships between the nutritional composition in macronutrients and fibers and the global acceptance of the Brazil nut beverages.

2.4.2. Online Questionnaire

The data from the neophobia scale were converted into scores based on the studies of [40,41], and participants were classified as neophilic, neutral, or neophobic based on their response scores. The choice-based conjoint data were analyzed with a multinomial logit model with random parameters using XLSTAT, and the aggregated utility and relative importance were estimated. The model considered the main effect of the six factors of the experimental design (price, selenium claim, functional claim, agrobiodiversity claim, 60+ claim, and taste), seeking to understand the effect of these factors and their levels on the participants’ choices. The willingness to pay (WTP) was calculated based on the coefficient of aggregate utility of the high price, together with that of each attribute. To accomplish this, the attribute coefficient was divided by the price coefficient, using a negative sign, since the price has a negative coefficient [44,45]. Socioeconomic and consumption data were expressed as percentages and compared using the Chi-square test.

All analyses were performed using the XLSTAT Statistical and Data Analysis solution. Significant values of p < 0.05 were considered in all analyses.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Part 1: Brazil Nut Beverage Development, Nutritional Composition, Microbiological and Sensory Analyses

3.1.1. Physicochemical and Microbiological Analyses

The beverages’ physicochemical results are shown in Table 3. As previously stated, the results of the lecithin concentrations were insignificant, so we decided not to use the emulsifier for the beverages’ final formulations.

Table 3.

Results of the nutritional composition for 200 mL of the beverages developed.

The beverages in general had a nutritional composition with good variety; moderate to adequate amounts of fiber, proteins, and lipids; low carbohydrate content; and varied concentrations of micronutrients (zinc, selenium, potassium, magnesium, and phosphorus) when compared to fruit beverages of the same flavor without added nuts. All beverages were superior to the CA beverage for at least one nutrient. This demonstrates that adding fruit can nutritionally enhance the formulations.

Regarding macronutrient content, there was a significant difference between the beverages, demonstrating an increase in proteins, fats, and fibers for the AI beverage, and an increase in carbohydrates for the JU beverage. Both these beverages also contributed to a higher caloric value among the beverages. This increase was expected due to the composition of these fruit pulps.

However, the same cannot be said for all the micronutrients. The AI beverage was superior to the others according to its content of sodium, potassium, magnesium, and calcium. The JU beverage had the second-highest content of sodium, potassium, magnesium, and calcium (not different from the MR beverage). For iron, the MR beverage was superior to the others. The selenium content did not differ among the beverages, indicating that the Brazil nuts were what contributed most to selenium’s high content in the samples.

According to Brazilian legislation [39], all beverages could be labeled “no added sugars”, “no dyes, preservatives and chemical additives”, and “rich in selenium”. The MR and CA beverages could also use the claim “Does not contain sodium”, since they both had less than 5 mg in the 200 mL serving; while AI and JU could be advertised as “Very low in sodium”. From the nutritional standpoint of the elderly, these beverages would be very adequate due to the increased contents of micronutrients such as selenium, magnesium, and zinc, all of which are considered essential nutrients for this stage of life [2].

Selenium is an essential nutrient that acts to promote antioxidant activity and to delay cellular aging in the elderly. The production of free radicals can be increased by the natural and physiological process of aging [25]. The beverages’ high selenium content is directly associated with adding Brazil nuts as an ingredient. The amount of selenium in fruit is often linked to the amount of this mineral in the soil. Nutrient-poor soils can produce plants with low amounts of minerals. The addition of Brazil nuts can counteract this shortage, enriching the beverages [24,46,47,48].

Zinc acts on cell replication and death, and gene expression and transcription, stabilizing membrane structures and cellular components, besides participating in immune function and cognitive development, factors that are particularly important for the elderly [49,50,51]. Magnesium has antiarrhythmic, cofactor, and adjuvant effects on glucose metabolism and insulin homeostasis. It acts on muscle tone and contractility, an attribute of paramount importance given that diseases such as sarcopenia often recur during the aging process [50,51,52].

In addition, it is important to note that the synergy of these micronutrients (selenium, magnesium, and zinc) has been extensively studied and found to be associated with preventing or at least slowing the progress of neurological diseases such as Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, and dementia [4,53,54,55,56].

Iron was also present in these beverages, which is valuable since it is a mineral that prevents and controls some types of anemia (iron deficiency) [57]. It is important to mention that non-heme iron (from these vegetables) has a lower absorption and metabolizable capacity than heme iron (mainly from meat sources). However, when combined with vitamin C, iron has a better absorption capacity and is more bioavailable [58,59,60]. This can be inferred from these beverages, since cashew fruits, like citrus fruits, contain significant amounts of vitamin C. Iron deficiency anemia can be associated with a low consumption of iron-source foods, especially meats, and a low intake of iron-source foods in the elderly is a recurring problem [50,61,62,63]. Therefore, this also is a disease of concern for this group.

Although the beverages are not considered to be high-calorie foods or food supplements, and therefore cannot receive this claim [25], the results obtained show that these beverages have the potential to supplement the calories and fats in the diet of the elderly, not as a substitute for a meal, but rather as a daily supplement. In general, people over the age of 60 years can find it challenging to reach their daily calorie target due to low food intake [3,50]. Hence, drinking a beverage able to supply nutrients and calories can be considered a practical way to improve health and wellbeing. Another relevant point is that the beverages have a low carbohydrate content and are sweetened with sucralose, making them beverages that can be indicated for diabetics, which is relevant since diabetes is a prevalent disease among the elderly [64,65].

Trends for Food and Beverages in 2024 [66] highlighted that one of the trends would be “age reframed”, where consumers, especially those approaching old age, are more concerned about their health, and thus seek a healthy diet that promotes the prevention or progression of ailments, such as diabetes and cardiovascular diseases. Thus, the beverages developed demonstrated innovative nutritional potential for the elderly, enabling them to meet their nutritional needs.

All the nut kernels analyzed for aflatoxins in our research were within the limits allowed by Brazilian legislation [67]. Contamination by aflatoxins produced by microorganisms of the Aspergillus genus is a recurring concern for these fruits, mainly due to their toxic effects [68,69].

A previous study found that this concern, as well as the allergenic factor, could prevent the general public from consuming these beverages, especially those who had never tried them before [32].

The results pointed out by the microbiological analysis of the beverages were also in line with the standards recommended by current legislation [70], as shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Results of the microbiological analysis of the prepared beverages.

The pasteurization process was efficient in guaranteeing microbiological safety, consequently allowing the beverages to be consumed. The choice of a preservation method for these products is of fundamental importance, since they are foods with the highest nutrient content and water activity (Aw), thus being a favorable environment for microorganisms to multiply. Although there are other more efficient and faster conservation mechanisms (microwave, electric pulse, and ultrasound) [17], pasteurization was a practical and affordable method to guarantee the microbiological safety of the beverages for consumption.

3.1.2. Sensory Acceptance and Purchase Intention of Brazil Nut Beverages

Most of the participants (n = 100) in this study were female (69%), with an average age of 64 years old. The results of the global acceptance and purchase intention are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Elderly people’s global acceptance and purchase intention of the beverages.

Among the beverages, the highest average global acceptance and purchase intention were JU and MR (not significantly different). The CA beverage had the second highest acceptance and purchase intention, while AI had the worst evaluation. In this regard, the flavored beverages performed better in both questions (except for AI), which suggests that the addition of flavoring, depending on the fruit, can improve adherence to nut beverages [17,71].

The AI beverage received the lowest score in both aspects evaluated. In the first case, consumers’ taste for the açaí fruit varies widely on a regional basis, so it is consumed in many ways in different places [72]. We believe this may have led many respondents to dislike the product. In this sense, our result corroborates a study by [73] that showed that consumers with high food neophobia reported less liking for fruit juices prepared with açaí.

Another hypothesis is that appearance (phase formation) led to the low acceptance of the açaí beverage. Due to the inefficiency of applying soy lecithin and our decision to remove it from the product, the beverages formed decanting phases when they were left to stand. This is explained by the immiscible nature of the product’s ingredients (water and fat from the nut), indicating the need for an alternative to emulsify this food matrix, such as enzymatic hydrolysis, or homogenization by ultrasound or high pressure, rather than the use of lecithin [74]. Texture is an essential factor and can impact the intention to buy or try the food by the elderly, mainly due to the issue of oral comfort and dysphagia. Hence, food products for this group need to be easy to swallow and digest, and pleasant in the mouth [75,76,77].

These beverages’ appearance and texture are a real challenge, so strategies are needed to overcome these limitations. In this sense, [78] stated that the texture of plant-based products can pose a barrier to consumption since they differ from products of animal origin. In this respect, if the goal is to mimic an animal product, they should be improved. Both their intrinsic and extrinsic influence factors should be studied. Therefore, our results agree with those authors’ findings that if the aim is to imitate a product based on cow’s milk, our expectations would have been frustrated given the product’s unpleasant appearance. However, our intention was not to develop a milk substitute but rather a plant-based beverage with an excellent nutritional profile for inclusion in the routine diets of the elderly.

The results of multiple factor analysis (Figure 2) showed that two selected components explained 99% of the total variation of the dataset. Dimension 1 explained 84.2% of the variation, while dimension 2 explained 14.8% and dimension 3 explained 1%. Dimension 1, which explained most of the variation, is related to nutritional composition (49.6%, r = 0.92) and global acceptance (50.4%, r = 0.93). The variables that contributed most to this dimension included carbohydrates (r = 0.98) and acceptance (r = 0.65). Proteins (r = −0.03), fats (r = −0.26), and fibers (r = −0.17) were negatively related to this dimension, which explained the relationship between nutritional composition and sensory acceptance. This result suggests that carbohydrates can contribute to consumers’ acceptance.

Figure 2.

Multiple factorial analysis for Brazil nut beverage samples (AI (açaí berry), JU (cashew apple), MR (strawberry) and CA (Brazil nut)). (A) Individuals. (B) Correlation circle of nutritional composition variables and global acceptance.

These data may also explain the participants’ comments about the lack of sweetness during the test. The fruits chosen for the formulation of the beverages contributed to the low content of carbohydrates (Table 3). JU and MR beverages had the highest carbohydrate content and the greatest global acceptance, reinforcing the relationship between this nutrient and the sensory evaluation. It is also interesting to observe that even though the beverages contained sucralose, the presence of fruits with a high carbohydrate content can intensify the perception of sweet taste. Undoubtedly, further tests with new proportions, organic acids analyses, or the choice of other sweeteners can be carried out, but it is interesting to note that among the elderly, mainly due to their greater use of various medications and the lesser production of saliva, their taste buds can be altered, therefore causing greater resistance to some flavors that are not very sweet [79,80]. For this reason, developing beverages with adequate amounts of sugar to please the palate can be a significant obstacle for the health food industry.

3.2. Consumer Perception of Brazil Nut Beverage (Online Study)

The sociodemographic and consumption characteristics of the participants (n = 220) of this study are shown in Table 6. The majority were female (52.7%), aged 60 to 69 (82.3%), from socioeconomic classes C and D (40.9% and 35.4%, respectively), residing in southeastern Brazil (50.9%), who reported rarely consuming nut beverages. Additionally, the participants were classified by the neophobia score, based on FNS. The majority of the respondents were “neutral”, followed by “neophobic”, with the smallest fraction being “neophilic”. Ref. [81] reported a relevant correlation between the neophobia of the elderly and the acceptance of functional foods due to fear of interaction with medications taken continuously by this group.

Table 6.

Sociodemographic variables and consumption of nut beverages by participants.

For the choice-based conjoint test, the results of aggregate utilities (Table 7) showed a significant effect of the price, with a low price having a positive influence and a high price having a negative impact. Plant-based product prices are still a great impediment to access and inclusion in the daily diet of these products, especially for the elderly in Brazil, who can be considered economically inactive [82,83].

Table 7.

Aggregate utilities of the main effects of participants from the CBC.

A curious result was that the “60+” claim showed no influence and was not significant for purchase intention. Our expectations were precisely the opposite, since we anticipated the participants to be more enthusiastic when they realized it was an age-specific product. One of the hypotheses for this result is that people consume products regardless of their age group, identification with a category, or belief in a need for special products for seniors [84].

The strawberry flavor had a negative influence, while the natural flavor had a positive effect, but this was not statistically significant, differing from what was observed after the experiment (Table 5). This can be explained by the fact that initially this flavor would not appeal to the consumers, at least not before tasting the product, so in this case, the presentation of another flavor that appealed to them or a more attractive appearance of the label could positively influence consumption [85]. Another point to note is the emotional arousal of tasters, which can indirectly impact both neophobia and the hedonic evaluation of products [86].

There was no significant interaction between the claim factors, leading us to believe that either on their own or together, these factors would have the same degree of relevance for the intention to buy the product. This could be positive, since there are specific market niches that encourage the production of clean label packaging for better identification and consumer information. Thus, the choice of information to place on labels so as not to compromise the layout must be made meticulously, considering each audience for which a product is intended [87,88,89].

The relative importance metric (Table 8) showed that the selenium claim was most important in the choice, followed by price and agrobiodiversity. The selenium claim stood out for having the highest relative importance of all the stratified groups, which was also observed for the public (33% relative importance). In the case of the beverages in this study, this claim was closely associated with Brazil nuts, which are a nutritional source of this mineral, indicating it would be a good idea to include this ingredient in beverages because this would encourage consumers to buy this type of product.

Table 8.

Relative importance of factors in the test of CBC.

Similar results to this study were found by [90], who observed that the main motivating factor for fruit juice consumption is flavor rather than health benefits and concluded that information about benefits is relevant only as long as there is sensory pleasure. It is interesting to note that this trend has been changing and that consumers’ perceptions of the types of product claims and flavors need to be verified on a case-by-case basis, i.e., the importance of a claim can vary for each group [89,91].

The willingness to pay (WTP) was estimated based on an upper price factor. The presence of the selenium claim was associated with a willingness to pay BRL 1.22 more than the high value of BRL 6.80 (in dollars, USD 0.26 more than USD 1.44), as did the functional claim (WTP of BRL 0.51 or USD 0.11 more than BRL 6.80 or USD 1.44), and the agrobiodiversity claim (WTP of BRL 0.99 or USD 0.21 more than BRL 6.80 or USD 1.44). The 60+ claim had a WTP of 0, demonstrating that consumers would not be willing to pay anything more than BRL 6.8 or USD 1.44. Compared to the flavors, participants’ WTP showed that they would be willing to pay more for the strawberry-flavored beverage (WTP of BRL 0.21 or USD 0.04 more than BRL 6.80 or USD 1.44) than for the natural flavor.

In the stratified CBC analysis for each group, neophiliacs tended to be more influenced by the agrobiodiversity claim (40.0%), followed by the selenium claim (20.9%) (Table 8). The aggregate utilities, although not significant, were positive for high price; the presence of claims such as selenium, functional, agrobiodiversity, and 60+; and natural flavor. The WTP showed the neophiliacs were not willing to pay more than the high price when there was the presence of any claim or natural flavor. Another highlight is that this group was made up entirely of occasional consumers of nut beverages. This is interesting because the population theoretically already familiar with this beverage is more concerned with other claims, such as sustainability and the extraction method by which these fruits are obtained than with taste and price, for example [92]. Ref. [93] observed a proportional relationship between sustainability-oriented motivations and reduced neophobia among consumers. In terms of income, consumers in the upper classes were less neophobic (0%), which may be explained by the issue of economic access to new products, and this population may be more accustomed to trying something new and more concerned about the issue of sustainability [94].

The group of neophilic consumers was entirely made up of woman, but this is a very low figure and not very representative of the sample, which is a limiting factor when comparing data. Despite this limitation, these results corroborate our previous studies [32], where the women were more willing to try nut-based beverages than men. The same finding was reported by Ref. [73] in their study of exotic tropical juices, and women and the elderly were more willing to try them.

Meanwhile, for neophobic consumers, the selenium claim was the standout (26.6%), followed by flavor (18.3%) and price (17.9%) (Table 8). In this case, with regard to the added value for neophobic consumers, the selenium claim (p = 0.023) and “natural” flavor claim (p = 0.023) positively influenced their choice. The WTP findings demonstrated that consumers were willing to pay more than the upper price (BRL 6.80 or USD 1.44) for natural flavor (WTP of BRL 1.02 or USD 0.22 more than high price), and in case of the presence of claims, namely selenium (WTP of BRL 1.48 or USD 0.33 more than the high price), functional (WTP of BRL 0.86 or USD 0.18 more than the high price), and agrobiodiversity (WTP of BRL 0.72 or USD 0.15 more than the high price). These consumers tended to show greater rejection of new foods, and in this study, the participants only partially consisted of regular consumers of nut beverages, making it interesting to highlight flavor as a factor that mattered in the choice. A possible explanation is that since these people are resistant to new flavors or new mixtures, choosing something more usual and close to normal, in this case, a traditional flavor, is an alternative to encourage experimentation with this product [95]. In this regard, [96] observed that food neophobia can negatively influence perceptions of less familiar products, such as plant-based beverages.

Another point observed, still in the group of neophobic consumers, is that the smallest fraction of this population stated “I don’t know what nut beverages are” and “I don’t consume and I’m not interested in trying them”, while the majority stated “I don’t consume nut beverages, but I’m interested in trying them” (Table 6). This result is important because it shows that the elderly, even if they are afraid to try new products, would be willing to try the beverages. Our results corroborate, to a certain extent, those of [97], who reported that if “new foods” had proven nutritional value and food safety, individuals with high neophobia would be willing to try them.

Neutral consumers divided the relative importance into the selenium claim (34.1%), price (27.5%), and agrobiodiversity claim (26.8%), with the aggregate utilities revealing that having the lowest price (p = 0.001) and the presence of claims such as selenium (p = 0.004) and the agrobiodiversity (p = 0.004) were significantly influential in their choice. A possible reason for this result is that a lower price could positively impact this population’s adherence to beverages regardless of their taste, i.e., a lower price would encourage greater consumption of these beverages. The WTP parameter demonstrated that consumers were willing to pay more than the high price (BRL 6.80 or USD 1.44) for strawberry flavor (WTP of BRL 0.15 or USD 0.03 more than the high price) and in case of the presence of claims such as selenium (WTP of BRL 1.24 or USD 0.26 more than the high price), functional (WTP of BRL 0.27 or USD 0.06 more than the high price), and agrobiodiversity (WTP of BRL 0.97 or USD 0.21 more than the high price).

4. Conclusions

Nut beverages could be an alternative for inclusion in the dietary routine of the elderly, as a calorie supplement and supplement to some nutrients (selenium, iron, magnesium, and zinc) in the diet of older people. The development of Brazil nut beverages has proven to be viable, especially with the mixture of fruit pulps. Our beverages presented good nutritional quality, with the presence of several minerals and macronutrients. Of the three fruits, the addition of açaí affected the fat, protein, and fiber more than the other two fruits. The addition of cashew apple pulp increased the carbohydrate content. In all cases, the microbiological quality was satisfactory, and the treatment applied to the Brazil nuts allowed for safe consumption. Soy lecithin did not have the expected technological effect and therefore was not used in formulating the beverages. Sensory analysis showed that cashew and strawberry beverages were the most accepted and had the highest purchase intention scores. These findings demonstrate that adding fruits can enhance acceptance and that the beverages developed seemed promising, but we noted some difficulties, such as the participants’ lack of knowledge about these beverages, in particular their appearance and sweetness.

In this sense, more studies and tools to improve these attributes need to be developed, as well as more widespread dissemination and awareness of the benefits and composition of these beverages. Evaluating the impact of the visual attributes on the consumption and purchase intention of the target audience and inexpensive and effective preservation methods are also topics to be addressed in future research, as is the choice of efficient, suitable, and affordable emulsifiers. The beverages tested have great innovative and nutritional potential for the supplementation of elderly consumers’ diets. Despite offering low caloric value, the beverages can supplement minerals such as selenium, which is a highlight for the beverages in this study, due to the presence of Brazil nuts.

Another important point was a better understanding of the effects of packaging factors on the purchase of products by the elderly. In this case, the low price, the presence of the selenium claim, functional claim, and agrobiodiversity claim, in addition to the natural flavor, had a positive impact on the potential purchase of the products. The age claim (60+) had no effect on the purchase, which may demonstrate that this cohort does not consume products due to advanced age considerations. In any case, more research is needed to better understand the effect of these factors on the choice of products for the elderly. It is also noteworthy that neophobic individuals showed a positive effect of the selenium claim and natural flavor claim on the intention to purchase the beverages. Despite the barrier of neophobia, the elderly can be considered as having a high expectation of consuming this class of beverages, thus forming a niche market that deserves attention due to their growing population in the country and their specific nutritional requirements.

Consumer perception of these factors, together with the sensory response to the beverages and their nutritional composition, can support the development of nut beverages that meet the needs of the elderly. Nevertheless, we acknowledge that one of its limitations was the absence of descriptive sensory tests. We thus recommend that future studies include in their sensory analyses the description of samples such as Brazil nut beverages, to better understand the impact of the presence of these attributes on acceptance. Another limitation was the online format, which limited the participation of elderly individuals, who tend not to have access to or familiarity with the use of computers and the internet.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.J.d.R.E. and O.F.-S.; methodology, V.J.d.R.E., I.P.L.d.C. and J.P.L.; software, A.V.d.M.M. and C.d.C.C.; formal analysis, D.d.G.C.F.d.S. and V.J.d.R.E.; investigation, V.J.d.R.E. and J.P.L.; resources, V.J.d.R.E.; data curation, D.d.G.C.F.d.S., A.V.d.M.M. and C.d.C.C.; writing—original draft preparation, V.J.d.R.E.; writing—review and editing, V.J.d.R.E., I.P.L.d.C. and O.F.-S.; visualization, O.F.-S., J.P.L. and D.d.G.C.F.d.S.; supervision, O.F.-S.; project administration, O.F.-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors are grateful for financial support provided by the Rio de Janeiro State Research Foundation (FAPERJ—grants E-26.202.749/2018, E-26/202.187/2020, E-26.201.302/2022, and E-26.210.290/2023); and by the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq—grant 311108/2021-0), EMBRAPA, and UNIRIO.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Research Committee of Federal University of the State of Rio de Janeiro (protocol code 57364922.4.0000.5285 and date of approval 30 June 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Chockalingam, A.; Singh, A.; Kathirvel, S. Chapter 12—Healthy aging and quality of life of the elderly. In Principles and Application of Evidence-Based Public Health Practice; Kathirvel, S., Singh, A., Chockalingam, A., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2024; pp. 187–211. ISBN 978-0-323-95356-6. [Google Scholar]

- Odoh, U.E.; Onyegbulam, C.M.; Onugwu, O.S.; Chikeokwu, I.; Odoh, L.C. Chapter 3—Nutrigenomics, plant bioactives, and healthy aging. In Plant Bioactives as Natural Panacea Against Age-Induced Diseases; Pandey, K.B., Suttajit, M., Eds.; Drug Discovery Update; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 49–61. ISBN 978-0-323-90581-7. [Google Scholar]

- Donini, L.M. Chapter 2—Control of food intake in aging. In Food for the Aging Population, 2nd ed.; Raats, M.M., de Groot, L.C.P.G.M., van Asselt, D., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing Series in Food Science, Technology and Nutrition; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2017; pp. 25–55. ISBN 978-0-08-100348-0. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmi, Y.; Shokati, A.; Hassan, A.; Aziz, S.G.-G.; Bastani, S.; Jalali, L.; Moradi, F.; Alipour, S. The Role of DNA Methylation in Progression of Neurological Disorders and Neurodegenerative Diseases as Well as the Prospect of Using DNA Methylation Inhibitors as Therapeutic Agents for Such Disorders. IBRO Neurosci. Rep. 2023, 14, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBGE—Censo 2021. Available online: https://censo2021.ibge.gov.br/2012-agencia-de-noticias/noticias/29505-expectativa-de-vida-dos-brasileiros-aumenta-3-meses-e-chega-a-76-6-anos-em-2019.html (accessed on 4 May 2021).

- Sulmont-Rossé, C.; Symoneaux, R.; Feyen, V.; Maître, I. Chapter 14—Improving food sensory quality with and for elderly consumers. In Methods in Consumer Research; Ares, G., Varela, P., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing Series in Food Science, Technology and Nutrition; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2018; Volume 2, pp. 355–372. ISBN 978-0-08-101743-2. [Google Scholar]

- Methven, L.; Jiménez-Pranteda, M.L.; Lawlor, J.B. Sensory and Consumer Science Methods Used with Older Adults: A Review of Current Methods and Recommendations for the Future. Food Qual. Prefer. 2016, 48, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Methven, L.; Rahelu, K.; Economou, N.; Kinneavy, L.; Ladbrooke-Davis, L.; Kennedy, O.B.; Mottram, D.S.; Gosney, M.A. The Effect of Consumption Volume on Profile and Liking of Oral Nutritional Supplements of Varied Sweetness: Sequential Profiling and Boredom Tests. Food Qual. Prefer. 2010, 21, 948–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarim, N.A.; Zainul Abidin, S.; Ariffin, F. Shelf Life Stability and Quality Study of Texture-Modified Chicken Rendang Using Xanthan Gum as Thickener for the Consumption of the Elderly with Dysphagia. Food Biosci. 2021, 42, 101054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keršienė, M.; Jasutienė, I.; Eisinaitė, V.; Pukalskienė, M.; Venskutonis, P.R.; Damulevičienė, G.; Knašienė, J.; Lesauskaitė, V.; Leskauskaitė, D. Development of a High-Protein Yoghurt-Type Product Enriched with Bioactive Compounds for the Elderly. LWT 2020, 131, 109820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivieri, K.; Freire, F.C.; Lopes, N.P.; Shiraishi, C.T.D.; Pires, A.C.M.S.; Lima, A.C.D.; Zavarizi, A.C.M.; Sgarbosa, L.; Bianchi, F. Chapter 14—Synbiotic yogurts and the elderly. In Yogurt in Health and Disease Prevention; Shah, N.P., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 259–271. ISBN 978-0-12-805134-4. [Google Scholar]

- Baugreet, S.; Kerry, J.P.; Botineştean, C.; Allen, P.; Hamill, R.M. Development of Novel Fortified Beef Patties with Added Functional Protein Ingredients for the Elderly. Meat Sci. 2016, 122, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farouk, M.M.; Yoo, M.J.Y.; Hamid, N.S.A.; Staincliffe, M.; Davies, B.; Knowles, S.O. Novel Meat-Enriched Foods for Older Consumers. Food Res. Int. 2018, 104, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, J.; Méndez, D.; Álvarez, M.; Sanmartin, B.; Vázquez, R.; Regueiro, L.; Atanassova, M. Design of Novel Functional Food Products Enriched with Bioactive Extracts from Holothurians for Meeting the Nutritional Needs of the Elderly. LWT 2019, 109, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, T.D.; de Freitas, B.C.B.; Moreira, J.B.; Zanfonato, K.; Costa, J.A.V. Development of Powdered Food with the Addition of Spirulina for Food Supplementation of the Elderly Population. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2016, 37, 216–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Pérez-Cueto, F.J.A.; Bølling Laugesen, S.M.; van der Zanden, L.D.T.; Giacalone, D. Older Consumers’ Attitudes towards Food Carriers for Protein-Enrichment. Appetite 2019, 135, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonas da Rocha Esperança, V.; Corrêa de Souza Coelho, C.; Tonon, R.; Torrezan, R.; Freitas-Silva, O. A Review on Plant-Based Tree Nuts Beverages: Technological, Sensory, Nutritional, Health and Microbiological Aspects. Int. J. Food Prop. 2022, 25, 2396–2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, B.Q.; Smetana, S. Review on Milk Substitutes from an Environmental and Nutritional Point of View. Appl. Food Res. 2022, 2, 100105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Ortega, D.L.; Lin, W. Food Values Drive Chinese Consumers’ Demand for Meat and Milk Substitutes. Appetite 2023, 181, 106392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, R.; Shekhar, S.; Prasad, K.; Kaur, R.; Shekhar, S.; Prasad, K. Functional Beverages: Recent Trends and Prospects as Potential Meal Replacers. Food Mater. Res. 2024, 4, e006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarcelli, E.; Iacopetta, D.; Ceramella, J.; Bonofiglio, D.; Conforti, F.L.; Aiello, F.; Sinicropi, M.S. The Role of Functional Beverages in Mitigating Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors: A Focus on Their Antidiabetic and Hypolipidemic Properties. Beverages 2025, 11, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasil, Ministério da Saúde. Vigitel Brasil 2023: Vigilância de Fatores de Risco e Proteção para Doenças Crônicas por Inquérito Telefônico; Ministério da Saúde: Brasília, Brazil, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Grochowicz, J.; Fabisiak, A.; Ekielski, A. Importance of Physical and Functional Properties of Foods Targeted to Seniors. J. Future Foods 2021, 1, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisht, A.; Singh, S.K.; Kaldate, R. Chapter 3.2.16—Bertholletia excelsa. In Naturally Occurring Chemicals Against Alzheimer’s Disease; Belwal, T., Nabavi, S.M., Nabavi, S.F., Dehpour, A.R., Shirooie, S., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 379–387. ISBN 978-0-12-819212-2. [Google Scholar]

- Avery, J.C.; Hoffmann, P.R. Selenium, Selenoproteins, and Immunity. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çetin, C.; Inan-Eroglu, E.; Akyol Mutlu, A.; Samur, G.; Ayaz, A. Relationship between Food Neophobia and Consumption of Functional Foods. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 37, S129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnopp, E.V.N.; dos Santos Vaz, J.; Schafer, A.A.; Muniz, L.C.; de Souza, R.D.L.V.; dos Santos, I.; Gigante, D.P.; Assunção, M.C.F. Food consumption of children younger than 6 years according to the degree of food processing. J. Pediatr. (Versão Port.) 2017, 93, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, V.H.; Moreira, P. Maternal food intake and socioeconomic status to tackle childhood malnutrition. J. Pediatr. (Versão Port.) 2016, 92, 546–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Vidigal, M.C.T.R.; Minim, V.P.R.; Simiqueli, A.A.; Souza, P.H.P.; Balbino, D.F.; Minim, L.A. Food Technology Neophobia and Consumer Attitudes toward Foods Produced by New and Conventional Technologies: A Case Study in Brazil. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 60, 832–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veríssimo, A.C.; Barbosa, M.C.D.A.; Almeida, N.A.V.; Queiroz, A.C.C.; Kelmann, R.G.; Silva, C.L.A.D. Association between the Habit of Reading Food Labels and Health-Related Factors in Elderly Individuals of the Community. Rev. Nutr. 2019, 32, e180207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caso, G.; Vecchio, R. Factors Influencing Independent Older Adults (Un)Healthy Food Choices: A Systematic Review and Research Agenda. Food Res. Int. 2022, 158, 111476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Rocha Esperança, V.J.; Paes Leme de Castro, I.; Santos Marques, T.; Freitas-Silva, O. Perception, Knowledge, and Insights on the Brazilian Consumers about Nut Beverages. Int. J. Food Prop. 2023, 26, 2576–2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association of Official Analytical Chemists. Official Methods of Analysis Chemists, 17th ed.; AOAC: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- APHA. Compendium of Methods for the Examination of Foods, 3rd ed.; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2001; 121p. [Google Scholar]

- Castro, I.M.; Anjos, M.R.; Teixeira, A.S. Análise de Aflatoxinas B1, G1, B2 e G2 em Castanha-do-Brasil, Milho e Amendoim Utilizando Derivatização Pós-Coluna no Sistema Cromatográfico CLAE/Kobra-Cell®/DFL.; Embrapa Agroindústria de Alimentos: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2013; Available online: https://www.infoteca.cnptia.embrapa.br/bitstream/doc/977550/1/2013CTE0198.pdf (accessed on 22 May 2025).

- Ribeiro, M.S.S.; Freitas-Silva, O.; Castro, I.M.; Teixeira, A.; Marques-da-Silva, S.H.; Sales-Moraes, A.C.S.; Abreu, L.F.; Sousa, C.L. Efficacy of Sodium Hypochlorite and Peracetic Acid against Aspergillus nomius in Brazil Nuts. Food Microbiol. 2020, 90, 103449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macfie, H.J.; Bratchell, N.; Greenhoff, K.; Vallis, L.V. Designs to Balance the Effect of Order of Presentation and First-Order Carry-Over Effects in Hall Tests. J. Sens. Stud. 1989, 4, 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawless, H.T.; Heymann, H. Sensory Evaluation of Food: Principles and Practices; Springer Science & Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-1-4419-6488-5. [Google Scholar]

- Brasil, Ministério da Saúde. Instrução Normativa—In N° 75, de 8 de Outubro de 2020 da Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária/Ministério da Saúde. Estabelece os Requisitos Técnicos para Declaração da Rotulagem Nutricional nos Alimentos Embalados; Ministério da Saúde: Brasília, Brazil, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pliner, P.; Hobden, K. Development of a Scale to Measure the Trait of Food Neophobia in Humans. Appetite 1992, 19, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro de Andrade Previato, H.D. Traducción y Validación de la Escala de Neofobia Alimentaria (ENA) Para. Nutr. Hosp. 2015, 32, 925–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassambara, A.; Mundt, F. factoextra: Extract and Visualize the Results of Multivariate Data Analyses; CRAN. 2021. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/factoextra/index.html (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Husson, F.; Josse, J.; Le, S.; Mazet, J. FactoMineR: Multivariate Exploratory Data Analysis and Data Mining; CRAN. 2024. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/FactoMineR/index.html (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Train, K.E. Discrete Choice Methods with Simulation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009; ISBN 978-1-139-48037-6. [Google Scholar]

- Louviere, J.J.; Hensher, D.A.; Swait, J.D. Stated Choice Methods: Analysis and Applications; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000; ISBN 978-1-107-71751-0. [Google Scholar]

- Gad, S.C. Selenium. In Reference Module in Biomedical Sciences; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; ISBN 978-0-12-801238-3. [Google Scholar]

- Kieliszek, M.; Serrano Sandoval, S.N. The Importance of Selenium in Food Enrichment Processes. A Comprehensive Review. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2023, 79, 127260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, M.A.; Brevik, E.C. Soil and human health. In Encyclopedia of Soils in the Environment, 2nd ed.; Goss, M.J., Oliver, M., Eds.; Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 2023; pp. 555–571. ISBN 978-0-323-95133-3. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, W.B. Vitamins and minerals. In Reference Module in Life Sciences; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; ISBN 978-0-12-809633-8. [Google Scholar]

- Moini, J.; Akinso, O.; Ferdowsi, K.; Moini, M. Chapter 8—Elderly health. In Health Care Today in the United States; Moini, J., Akinso, O., Ferdowsi, K., Moini, M., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023; pp. 171–191. ISBN 978-0-323-99038-7. [Google Scholar]

- Nohr, D. Micronutrients. In Reference Module in Food Science; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; ISBN 978-0-08-100596-5. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco, A.; Blanco, G. Chapter 29—Essential minerals. In Medical Biochemistry, 2nd ed.; Blanco, A., Blanco, G., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; pp. 779–810. ISBN 978-0-323-91599-1. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, W.; Wang, S.; Gu, J.; Yu, L. Selenium and Human Nervous System. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2023, 34, 108043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lin, S.; Gu, Z.; Chen, L.; He, B. Zinc-Dependent Deacetylases (HDACs) as Potential Targets for Treating Alzheimer’s Disease. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2022, 76, 129015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, H.S. Chapter 15—Selenium use in epilepsy. In Vitamins and Minerals in Neurological Disorders; Martin, C.R., Patel, V.B., Preedy, V.R., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023; pp. 245–261. ISBN 978-0-323-89835-5. [Google Scholar]

- Toffa, D.H.; Li, J. Chapter 4—Magnesium and Alzheimer’s disease. In Vitamins and Minerals in Neurological Disorders; Martin, C.R., Patel, V.B., Preedy, V.R., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023; pp. 47–63. ISBN 978-0-323-89835-5. [Google Scholar]

- Pietrangelo, A.; Torbenson, M. Chapter 4—Disorders of iron overload. In MacSween’s Pathology of the Liver, 8th ed.; Burt, A., Ed.; Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2024; pp. 295–329. ISBN 978-0-7020-8228-3. [Google Scholar]

- Celis, A.I.; Relman, D.A.; Huang, K.C. The Impact of Iron and Heme Availability on the Healthy Human Gut Microbiome In Vivo and In Vitro. Cell Chem. Biol. 2023, 30, 110–126.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, C.E.; Bhagavan, N.V. Chapter 25—Hemoglobin and metabolism of iron and heme. In Essentials of Medical Biochemistry, 3rd ed.; Ha, C.E., Bhagavan, N.V., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2023; pp. 573–611. ISBN 978-0-323-88541-6. [Google Scholar]

- Wessling-Resnick, M. Chapter 14—Iron: Basic nutritional aspects. In Molecular, Genetic, and Nutritional Aspects of Major and Trace Minerals; Collins, J.F., Ed.; Academic Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 161–173. ISBN 978-0-12-802168-2. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, P.C.; Vicente, F. Chapter 20—Meat nutritive value and human health. In New Aspects of Meat Quality, 2nd ed.; Purslow, P., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing Series in Food Science, Technology and Nutrition; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2022; pp. 561–577. ISBN 978-0-323-85879-3. [Google Scholar]

- Rémond, D. The Contribution of meat in the diet of senior citizens. In Reference Module in Food Science; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; ISBN 978-0-08-100596-5. [Google Scholar]

- Talukder, J. Chapter 60—Role of transferrin: An iron-binding protein in health and diseases. In Nutraceuticals, 2nd ed.; Gupta, R.C., Lall, R., Srivastava, A., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 1011–1025. ISBN 978-0-12-821038-3. [Google Scholar]

- Kolcu, M.; Bulbul, E.; Celik, S.; Anataca, G. The Relationship between Health Literacy and Successful Aging in Elderly Individuals with Type 2 Diabetes. Prim. Care Diabetes 2023, 17, 473–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludwig, S. Diabetes in the elderly. In Practical Diabetes Care for Healthcare Professionals, 2nd ed.; Ludwig, S., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 107–126. ISBN 978-0-12-820082-7. [Google Scholar]

- Mintel. 2024 Global Food and Drink Trends; Mintel: Chicago, IL, USA, 2024; Available online: https://insights.mintel.com/rs/193-JGD-439/images/Mintel_2024_Global_Food_and_Drink_Trends_English.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Brasil, Ministério da Saúde. Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária (ANVISA). Instrução Normativa nº 160, de 1° de julho de 2022: Estabelece os Limites Máximos Tolerados (LMT) de Contaminantes em Alimentos; Ministério da Saúde: Brasília, Brazil, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Freitas-Silva, O.; Venâncio, A. Brazil Nuts: Benefits and Risks Associated with Contamination by Fungi and Mycotoxins. Food Res. Int. 2011, 44, 1434–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas-Silva, O.; de Souza Coelho, C.C.; Trombete, F.M.; da Conceição, R.R.P.; Ribeiro-Santos, R. Chemical degradation of aflatoxins. In Aflatoxins in Food: A Recent Perspective; Hakeem, K.R., Oliveira, C.A.F., Ismail, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 233–258. ISBN 978-3-030-85762-2. [Google Scholar]

- Brasil, Ministério da Saúde. Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária (ANVISA). Instrução Normativa nº 60/2019: Estabelece as Listas de Padrões Microbiológicos de Alimentos; Ministério da Saúde: Brasília, Brazil, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, D.d.S.; Silva, S.d.S.; de Figueiredo, R.W.; de Menezes, F.L.; de Castro, J.S.; Pimenta, A.T.Á.; dos Santos, J.E.d.Á.; do Nascimento, R.F.; Gaban, S.V.F. Production of Healthy Mixed Vegetable Beverage: Antioxidant Capacity, Physicochemical and Sensorial Properties. Food Sci. Technol 2021, 42, e28121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silveira, J.T.; da Rosa, A.P.C.; de Morais, M.G.; Victoria, F.N.; Costa, J.A.V. An Integrative Review of Açaí (Euterpe oleracea and Euterpe precatoria): Traditional Uses, Phytochemical Composition, Market Trends, and Emerging Applications. Food Res. Int. 2023, 173, 113304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbe, S.; Verbeke, W.; Deliza, R.; Matta, V.; Van Damme, P. Effect of a Health Claim and Personal Characteristics on Consumer Acceptance of Fruit Juices with Different Concentrations of Açaí (Euterpe oleracea Mart.). Appetite 2009, 53, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, R.R.; Stephani, R.; Perrone, Í.T.; de Carvalho, A.F. Plant-Based Proteins: A Review of Factors Modifying the Protein Structure and Affecting Emulsifying Properties. Food Chem. Adv. 2023, 3, 100397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, J.M.; Covacevich, L. Designing Foods for an Increasingly Elderly Population: A Challenge of the XXI Century. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2023, 51, 101037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego, M.; Barat, J.M.; Grau, R.; Talens, P. Compositional, Structural Design and Nutritional Aspects of Texture-Modified Foods for the Elderly. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 119, 152–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorieau, L.; Septier, C.; Laguerre, A.; Le Roux, L.; Hazart, E.; Ligneul, A.; Famelart, M.-H.; Dupont, D.; Floury, J.; Feron, G.; et al. Bolus Quality and Food Comfortability of Model Cheeses for the Elderly as Influenced by Their Texture. Food Res. Int. 2018, 111, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, R.; LeBlanc, J.; Gorman, M.; Ritchie, C.; Duizer, L.; McSweeney, M.B. A Prospective Review of the Sensory Properties of Plant-Based Dairy and Meat Alternatives with a Focus on Texture. Foods 2023, 12, 1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Li, X.; Wu, C.; Zhang, R.; Durrani, D.K. The Impact of Expectation Discrepancy on Food Consumers’ Quality Perception and Purchase Intentions: Exploring Mediating and Moderating Influences in China. Food Control 2022, 133, 108668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordin, S. Chapter 3—Sensory perception of food and aging. In Food for the Aging Population, 2nd ed.; Raats, M.M., de Groot, L.C.P.G.M., van Asselt, D., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing Series in Food Science, Technology and Nutrition; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2017; pp. 57–82. ISBN 978-0-08-100348-0. [Google Scholar]

- Stratton, L.M.; Vella, M.N.; Sheeshka, J.; Duncan, A.M. Food Neophobia Is Related to Factors Associated with Functional Food Consumption in Older Adults. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 41, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malek, L.; Umberger, W.J. Protein Source Matters: Understanding Consumer Segments with Distinct Preferences for Alternative Proteins. Future Foods 2023, 7, 100220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szakos, D.; Ózsvári, L.; Kasza, G. Health-Related Nutritional Preferences of Older Adults: A Segmentation Study for Functional Food Development. J. Funct. Foods 2022, 92, 105065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Chan, S.H.W.; Xu, Y.; Yeung, K.C. Determinants of Life Satisfaction and Self-Perception of Ageing among Elderly People in China: An Exploratory Study in Comparison between Physical and Social Functioning. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2019, 84, 103910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallas, Z.; Vitale, M.; Gil, J.M. Health Innovation in Patty Products. The Role of Food Neophobia in Consumers’ Non-Hypothetical Willingness to Pay, Purchase Intention and Hedonic Evaluation. Nutrients 2019, 11, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, E.; Niimi, J.; Collier, E.S. The Relationship between Food Neophobia and Hedonic Ratings of Novel Foods May Be Mediated by Emotional Arousal. Food Qual. Prefer. 2023, 109, 104931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noguerol, A.T.; Pagán, M.J.; García-Segovia, P.; Varela, P. Green or Clean? Perception of Clean Label Plant-Based Products by Omnivorous, Vegan, Vegetarian and Flexitarian Consumers. Food Res. Int. 2021, 149, 110652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybak, G.; Burton, S.; Johnson, A.M.; Berry, C. Promoted Claims on Food Product Packaging: Comparing Direct and Indirect Effects of Processing and Nutrient Content Claims. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 135, 464–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tønnesen, M.T.; Hansen, S.; Laasholdt, A.V.; Lähteenmäki, L. The Impact of Positive and Reduction Health Claims on Consumers’ Food Choices. Food Qual. Prefer. 2022, 98, 104526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidigal, M.C.T.R.; Minim, V.P.R.; Carvalho, N.B.; Milagres, M.P.; Gonçalves, A.C.A. Effect of a Health Claim on Consumer Acceptance of Exotic Brazilian Fruit Juices: Açaí (Euterpe oleracea Mart.), Camu-Camu (Myrciaria dubia), Cajá (Spondias lutea L.) and Umbu (Spondias tuberosa Arruda). Food Res. Int. 2011, 44, 1988–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicklaus, S.; Tournier, C. 11—Relationships between early flavor/texture exposure, and food acceptability and neophobia. In Flavor, 2nd ed.; Guichard, E., Salles, C., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2023; pp. 301–327. ISBN 978-0-323-89903-1. [Google Scholar]

- Piracci, G.; Casini, L.; Contini, C.; Stancu, C.M.; Lähteenmäki, L. Identifying Key Attributes in Sustainable Food Choices: An Analysis Using the Food Values Framework. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 416, 137924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, A.A.; Kang, J. It’s Not Just about the Food: Motivators of Food Patterns and Their Link with Sustainable Food Neophobia. Appetite 2022, 174, 106008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, X.-J.; Cheah, J.-H.; Ngo, L.V.; Chan, K.; Ting, H. How Do Crazy Rich Asians Perceive Sustainable Luxury? Investigating the Determinants of Consumers’ Willingness to Pay a Premium Price. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 75, 103502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Chung, S.-J. Flavor Principle as an Implicit Frame: Its Effect on the Acceptance of Instant Noodles in a Cross-Cultural Context. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 93, 104293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, S.R.; Giacalone, D. Barriers to Consumption of Plant-Based Beverages: A Comparison of Product Users and Non-Users on Emotional, Conceptual, Situational, Conative and Psychographic Variables. Food Res. Int. 2021, 144, 110363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes de Souza, P.; Rosane, P.; Azeredo, D.; da Silva, T.T.C.; Carneiro, C.d.S.; Junger Teodoro, A.; Menezes Ayres, E.M. Food Neophobia, Risk Perception and Attitudes Associations of Brazilian Consumers towards Non-Conventional Edible Plants and Research on Sale Promotional Strategies. Food Res. Int. 2023, 167, 112628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).