Understanding the Wine Consumption Behaviour of Young Chinese Consumers

Abstract

1. Introduction

Research Question

- Q1: What motivates young Chinese consumers to buy wine? This question aims to identify the underlying drivers behind their purchase decisions.

- Q2: What are the sensory preferences of young Chinese consumers when drinking wine? This aims to understand their taste and preference patterns.

- Q3: What are the preferred wine retail channels of young Chinese consumers? This will explore their preferred platforms and methods for purchasing wine.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Key Young Chinese Consumer Segments

2.1.1. Millennials

2.1.2. Post-Millennials

2.2. Chinese Wine Market Structure

2.3. Chinese Consumers Behaviour in Wine Consumption

2.4. Global Wine Consumers and Wine Consumption

3. Method

Data Collection and Analysis

4. Findings

4.1. What Motivates Young Chinese Consumers to Buy Wine?

4.1.1. Social Settings

“Drinking feels like a tradition. In China, it has a long history. We often say dinner isn’t complete without alcohol. For example, if only a couple of people drink, the dinner feels dull. Wine helps warm the atmosphere up.”—CL

“To me, the word ‘occasion’ includes not just time and place, but also who you’re with and why. Most of my wine drinking happens at birthdays, weddings, or get-togethers with friends or family. These are joyful events, and drinking wine makes them even happier.”—ZXK

“At home, we usually have wine with dinner. For example, on Saturday nights, my mom would cook a big meal—Chinese or Western—and choose a bottle of red wine to go with it.”—LYS

“My mother drank wine every day. Just a small cup—usually white wine.”—LSH

“Wine helps me relieve stress and strengthens my friendships. It brings a spark to life. I don’t think of it as a ritual—just something I enjoy when the mood and people feel right.”—ZJY

“At parties, we just casually talk—sometimes about the wine itself. It’s really nice to chat with people who share the same interests. Our friendships grow naturally through these conversations. We don’t get drunk; we drink for the joy of it.”—ZT

“Wine helps me relax and brings me closer to others… it adds excitement to life. I don’t really treat drinking as a ritual—it’s just that the right time and the right people make me want to drink.”—ZJY

“During the party we just randomly chat or talk about our own understanding of the wine we’re having. It feels very good to talk with the people who have the same interests. Our friendships are growing automatically during the process.”—ZT

“I drink wine when I’m happy—like on my birthday or during holidays. Just seeing wine makes me feel cheerful. It’s a happy kind of drink.”—WYL

“To me, wine feels casual and romantic. I associate it with Western-style dates—like having wine when you’re out with your boyfriend.”—QYS

“Wine, especially red wine, is perfect for a date. But even at home, having some wine helps create a warm, intimate vibe.”—ZMK

4.1.2. Lifestyle

“For us, it was simple—we studied wine at university, so we had to drink it. But the more I learned, the more interested I became—not just in the wine itself, but in everything from grape growing to bottling. There’s so much richness in the history and culture—it makes me want to keep exploring.”—ZJY

“Last time we visited a winery, my friend was there working as a sales rep. She was so patient and introduced a lot of wines to us. We ended up buying a bottle of Riesling she recommended. The whole experience felt professional and atmospheric—it made me feel like the wine we bought was something high-end.”—KW

“I tend to drink more when I travel. If I’m staying somewhere for a couple of nights, I usually order a bottle of wine to enjoy during the trip.”—XQ

“I really got into Western cooking—like making cream of mushroom soup. One recipe mentioned using dry white wine, so I looked it up and bought a bottle to try. After I made the dish, I thought the wine’s acidity balanced out the creaminess perfectly—it cut through the heaviness and brought out a richer, more complex flavour. That’s what got us interested in white wine in the first place.”—QYS

“I think wine completes a Western-style dinner—it feels more formal and special. For me, it’s like a ritual. I enjoy following little rituals in life. Like, if you have a beautiful wine glass, isn’t it a shame not to use it? That’s the feeling—it’s about making moments feel meaningful.”—KW

“I like sparkling wines, especially Champagne. I enjoy the acidity—it’s kind of like coffee. The tasting process for wine and coffee is actually pretty similar, though the aging and complexity evolve in different ways.”—L

“Late at night, after the kids are asleep, I turn on a little lamp and pour myself a glass of wine. It feels a bit luxurious—but I’m not showing off on social media or anything. It’s more like I’m quietly searching for something for myself.”—L

“I usually drink alone and have a collection of glasses I use just for wine. I might light some candles or aromatherapy—it creates a nice vibe. No one’s rushing me, no pressure to drink fast like at parties. I’m not doing it for photos or anyone else. I just want to enjoy the taste, to take it slow. And sometimes, when I want to feel a little happy or tipsy, wine is what I choose.”—QSY

4.1.3. Wine Marketing

“Marketing strategies, especially for the strategies used in China. The internet influencers in social apps are doing importantly in promoting wine. They enlighten and lead people to wine.”—MJJ

”The price of the wine we should use highly relates to the reputation of the gifted person. If he or she has a higher social status or a higher salary, they might drink wine with a price 150 RMB to 200 RMB. When selecting gift for this group of people, we might need to add another $5.”—CL

“If it is for a commercial purpose like if there’s genuine market value then my priorities would be different. I’d definitely look for something that’s publicly available and whose value is already recognized by the market.”—XQ

“If I’m giving wine to a friend—like something we’d drink together—then I’d usually pick something around 200 or 300 yuan. It needs to taste good, of course. But if it’s for an elder, or a more formal occasion, then I’d probably choose something more expensive.”—WXY

“I wouldn’t give wine to my elders—I don’t earn money myself, so I don’t see the point in giving gifts like that.”—MS

4.1.4. Social Media Influence

“(Social media) posting about it, or sharing a recommendation or maybe seeing someone else recommend it that’s when I get tempted to try it.”—LYS

“(Lady Penguin) for example she’ll explain what makes a wine different from others, or why it’s special. Sometimes she recommends a full-score wine that isn’t even that expensive—maybe just over 200 yuan. That makes me feel like I might actually try it.”—L

“On Xiaohongshu, I don’t really trust the professional wine influencers they often feel like models or marketing tools. But there are some regular users who truly love wine and share their own reviews. You can ask them questions, and they’ll reply in detail. If someone like that recommends something, I find them trustworthy.”—MS

“Professional wine scores feel relatively objective—they’re usually not fake. Even if people don’t fully understand the wine’s style or quality, the score gives them a sense of security.”—ZXK

4.2. What Are the Sensory Preferences of Young Chinese Consumers When Drinking Wine?

“I’d prefer to drink this kind of wine at a formal dinner—with my boss or older relatives. It feels more proper. In China, we don’t usually have white or rosé wine at formal occasions. Older people don’t really see those as proper alcohol. Red wine is more respectable in their eyes.”—ZT

“I prefer to drink white wine with friends. It just fits my experiences better. I don’t really enjoy red wine, but I’m happy to share white wine with others. For me, white wine is something to enjoy socially.”—WYL

“If I had to choose, I’d go with a sweet Riesling. I don’t like wines that are too astringent. A nice aroma and a bit of sweetness would be much better for me.”—MJJ

“I’ve only had rosé with my girlfriends. It’s perfect for girls’ parties—rosé just makes us happy when we see it. I usually buy it when they visit my place. To me, rosé is a pretty wine that’s made for girls.”—KW

“I think this wine would be perfect to share with some young, outgoing women over dinner.”—CL

“White wine with semi-dry taste but hardly buy sweet ones. I would only buy semi-sweet white wine when I need it for a party or a gift.”—ZT

“I would share this wine with some young and outgoing ladies in dinner.”—CL

“White wine gives off a refreshing vibe—like something you’d enjoy at a picnic. It pairs well with seafood and just feels light and crisp.”—QYS

“I joined a wine club at university that was run by other students who love wine. I only went to a couple of their events, but after that I usually drank wine alone in my dorm.”—MJJ

“After going to that German wine show, I really started to like this kind of Riesling. It felt just right for my taste.”—ZMK

4.3. What Are the Preferred Wine Retail Channels of Young Chiese Consumers?

“If we order wine before noon, it usually gets shipped the same afternoon. If it’s through Shun Feng, we normally receive it the next day. Slower deliveries might take one more day.”—ZJY

“Chinese supermarkets don’t offer much choice there are usually fewer than ten kinds, even less for white wines. Maybe in cities like Beijing or Shanghai there are more options, but in smaller cities there’s almost nothing.”—ZJY

“When I visited a winery and tasted the wine, I really liked it. Later, I bought a bottle and gave it to a friend as a souvenir—it felt special.”—XQ

“For me, 100 to 200 RMB is my usual price range. Anything over 300 feels expensive. Even though I don’t earn much, I still feel that wine under 100 RMB usually doesn’t taste good.”—ZJY

“I usually buy a Riesling in the 100 RMB range at the supermarket. Sometimes I find one for just over 50. But when I’m at a winery, I prefer to buy what I’ve tasted—even if it’s more expensive, like over 200 RMB. It just feels more worth it.”—KW

“It depends on the leader’s level. A 100 RMB bottle won’t impress someone important. You’d probably need something around 500 RMB—or even 1000—depending on their status.”—CL

“I’d only gift wine to friends who don’t really understand wine but still drink it occasionally. For them, I’d choose something around 200 RMB, preferably with delicate packaging.”—ZJY

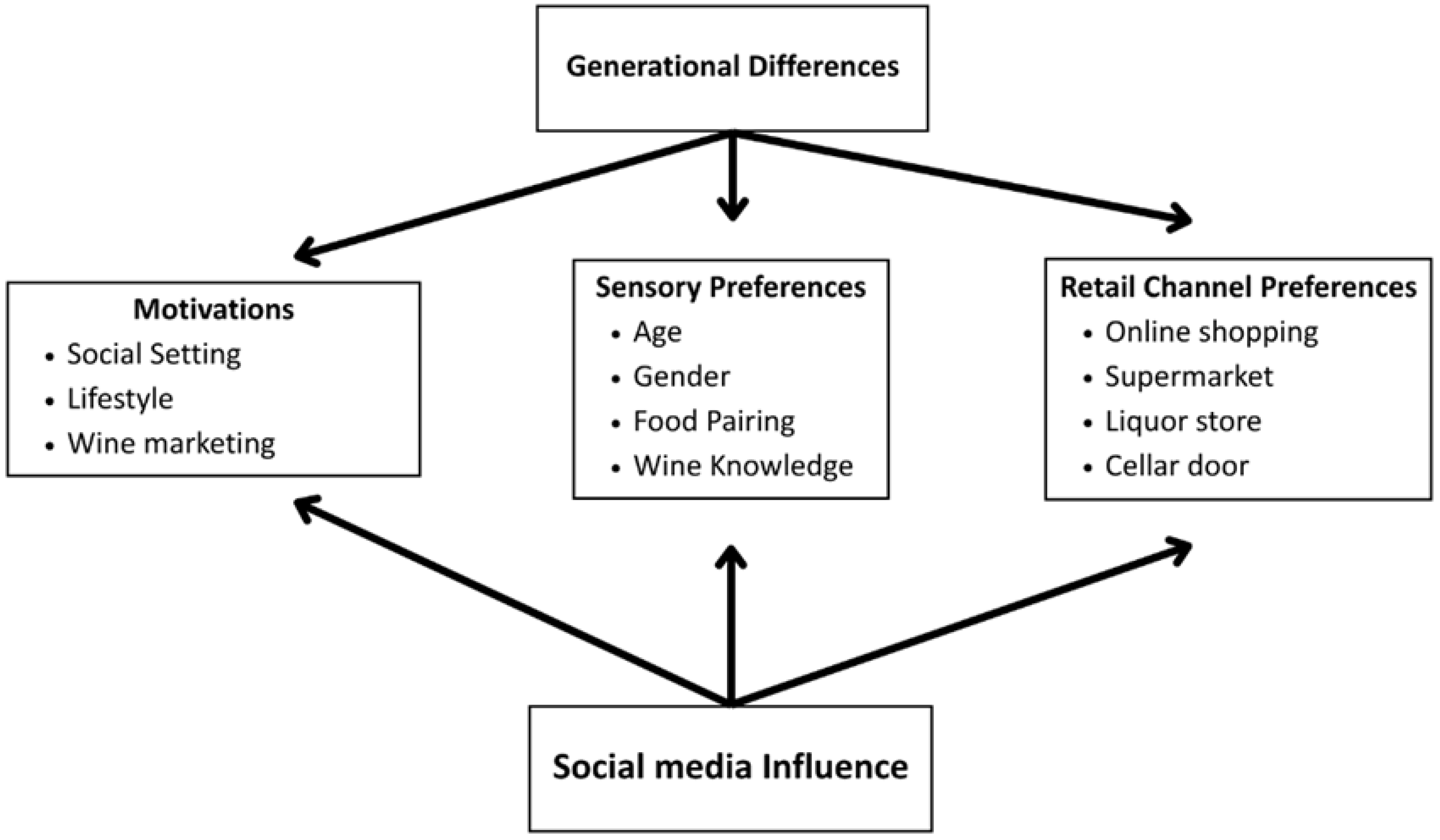

5. Conceptual Model and Discussion

5.1. Generational Motivations for Wine Consumption

5.2. Retail Channel Engagement

5.3. Experiential Consumption Patterns

6. Conclusions

7. Limitation and Further Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Participant Form

| Participant Code | Gender | Age | Occupation | Location | Group Number |

| WYL | Female | 35 | Postdoc of Agriculture | Beijing | FG1 |

| KW | Female | 28 | Food company technician | Chengdu | FG1 |

| ZJY | Female | 26 | Wine industry worker | Jinan | FG1 |

| ZZK | Male | 33 | Hospitality | Chongqing | FG1 |

| LL | Male | 34 | Hospitality | Chongqing | FG1 |

| XQ | Female | 35 | Tourism marketing | Beijing | FG1 |

| MJJ | Female | 23 | University student | Yunnan | FG2 |

| WXY | Female | 21 | University student | Beijing | FG2 |

| ZJS | Female | 21 | University student | Beijing | FG2 |

| JYS | Female | 23 | University student | Beijing | FG2 |

| LYS | Female | 22 | University student | Beijing | FG2 |

| QYS | Female | 23 | University student | Beijing | FG2 |

| YWY | Male | 28 | Building company worker | Chengdu | FG3 |

| CL | Male | 35 | Staff in state-own enterprise | Beijing | FG3 |

| ZT | Male | 27 | Wine industry worker | Jinan | FG3 |

| ZXK | Male | 36 | Doctor of Wine Science | Beijing | FG3 |

| L | Male | 34 | Barista | Beijing | FG3 |

| LSH | Male | 24 | University student | Beijing | FG4 |

| WZ | Male | 21 | University student | Beijing | FG4 |

| ZMK | Male | 25 | University student | Beijing | FG4 |

| WHT | Male | 24 | University student | Beijing | FG4 |

| BZT | Male | 26 | University student | Beijing | FG4 |

| MS | Male | 24 | University student | Beijing | FG4 |

Appendix B. Thematic Coding Structure

| Representative Quotes | First-Order Level | Second-Order Level | Key Categories |

| “To be honest, I had to drink for social activities when I worked in China. Since I quit from the job, I barely drank alcohol for my own.”—WYL | Business events | Social Setting | Motivation |

| “Our friendships are growing automatically during the process. We’ll not be drunk. We drink mainly for the happy feeling.”—ZT | Friend get-togethers | ||

| “I think wine is a casual drink, and my first reaction is Western occasions, such as dating. When you have a date with your boyfriend, you drink wine more often.”—QYS | Romantic occasions | ||

| “We learnt Wine in university, so we got to drink. …And also the history and culture, they are full or richness and make me willing to keeping drinking.”—ZJY | Overseas experience | Lifestyle | |

| “I think drinking wine can make a Western dinner complete. The dinner would become more formal because of the wine”—KW | Western-style luxury cuisine | ||

| “In the dead of night, the children are asleep, and then you turn on a small light here, and then drink wine, and this may be very luxury, but I don’t show off that I don’t have any friends to post, but it seems to be looking for it myself”—L | Self-indulgence. | ||

| “If it’s for a commercial purpose—like if there’s genuine market value—then my priorities would be different. I’d definitely look for something that’s publicly available and whose value is already recognized by the market.”—XQ | Gift-giving tradition | ||

| “But generally if you really send it to a friend, and then two people drink it together, or if you really want to give a friend a taste, it will be two or three hundred, and then it will taste good, and if there is a situation, it may be sent to an elder or something, it may be more expensive.”—WXY | Wine marketing | ||

| “For example, he will say what is the difference between this wine and others, or this is a special Internet celebrity, for example, I buy it now This is a full score wine, and then the full score wine is not very expensive, it may not be so expensive, it may be in the early 2000s, I thought I might be able to buy it.”—L | Social media Influencers | Social media influence | |

| “Marketing strategies, especially for the strategies used in China. The internet influencers in social apps are doing importantly in promoting wine. They enlighten and lead people to wine.”—MJJ | Digital wine retailers | ||

| “Sometimes you will find that some people who live in social media really like this thing to write by themselves, and then I feel that you say that he must have his own experience in it…I think he is trustworthy people will be OK with you.”—MS | Electronic word of mouth | ||

| “I would like to drink this wine in a formal dinner, with such as my boss or my older relatives because this (red) wine seems more formal than the previous two. It might relate to the environment in China. We don’t have white and rose wine very often. The old people would not take them as a kind of alcohol if I used them. Red wine would be more formal, decent to them.”—ZT | Red wine with older | Age | Sensory Preference |

| “I would like to drink with friend for the white wine. This relates my experiences. I don’t like red wine but don’t mind to share white wine with my friends so to me white wine is the one enjoying with friends.”—WYL | White wine | ||

| “If I have to pick one now…a good smell one with sweet taste would be better.”—MJJ | Sweet wine | Gender | |

| “I would choose wine with a medium or low tannin content… Normally I would buy dry red wine. I might also buy white wine with semi-dry taste but hardly buy sweet ones. I would only buy semi-sweet white wine when I need it for a party or a gift.”—ZT | Red wine | ||

| “I don’t have this kind of friend in reality but I had I would share this (Rose) wine with some young and outgoing ladies in dinner.”—CL | Rose wine | ||

| “I only had rose wine with my girlfriends. It would suit for girl’s parties because girls would become happy when seeing it… Rose wine is more like a good-looking wine for girls to me.”—KW | Rose wine | ||

| “White wine gives off a very refreshing vibe, like something you’d have at a picnic. It goes well with seafood—usually just feels light and fresh.”—QYS | White wine | Food and wine pairing | |

| “Then at the wine show, especially after we went to the last German wine show, I think this kind of Riesling is just right for me to drink.”—ZMK | White wine | Wine knowledge | |

| “For us if we ordered wine before 12pm, the wine will be shipped out that afternoon and if we’re using Shun Feng’s delivery service, we would normally receive the wine the second day. For a slower delivery, it might be the day after.”—ZJY | Buy wine from online | Online shops | Preferred Channels |

| “There is no many choices in Chinese supermarket, especially for wine.”—ZJY | Supermarket | supermarkets and liquor stores | |

| “When I was buying liquor (in a store), I saw a friend, because I went to the winery, and then I drank it. I thought it was really good, and then I gave it to that friend, which was a souvenir.”—XQ | Wine tourism | Cellar door | |

| “When I’m in winery, I would like to buy the one I tasted. The price might be higher than the usual, let’s say a bottle of wine more than 200RMB.”—KW |

Appendix C. Focus Group Questions/Guide/Protocol

- What is your preferred type of wine? (red, white, rose, others?)

- Why? (reasons)

- Where do you drink wine? (home, university, restaurant, parties, etc?)

- How frequently do you drink wine? (occasionally, everyday, weekends, special occasions, etc.)

- How much wine do you consume? (per week/month?)

- Who do you drink wine with? (alone, family, friends, strangers at a bar?)

- What was your first experience with drinking wine?

- How does drinking wine make your feel? (happy, celebrations, sad,)

- Opinion of wine drinkers (vs other drinks)

- What is special about wine?

- When do you buy wine?

- Who influences your wine purchase decisions? (friends, family, influencers)

- How do you find information when you want to buy wine?

- Where do you buy from? (channels e.g., supermarket, liquor store, wine club, online, etc.)

- Price points—how much are you willing to pay for wine?

- ○

- Personal consumption

- ○

- Special occasions (what are they?)

- ○

- Gifting

- Colour

- Taste—sweet, dry, etc.

- Terroir

- Country of origin (French, Italian, NZ, Australian, etc)

- Labels

- Luxury/premium wine

- Vintage

- Others?

- Ask if there was anything else they want to share about their wine consumption.

- Thank everyone for their time.

References

- Ministry of Commerce of The People’s Republic of China. The Final Decision of the Anti-Dumping Investigation of Imported Australian Wine. 2021. Available online: https://www.mofcom.gov.cn/article/ae/ai/202103/20210303047619.shtml (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Prakash, K.; Tiwari, P. Millennials and Post Millennials: A Systematic Literature Review. Publ. Res. Q. 2021, 37, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z. Study on the fashion consumption characteristics of millennials. Mod. Bus. 2019, 28, 21–22. [Google Scholar]

- Noormohamed, N.A. Luxurious Lifestyles: Marketing to Chinese Millennials. Compet. Forum 2019, 17, 425–430. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.-K. Impacts of Digital Technostress and Digital Technology Self-Efficacy on Fintech Usage Intention of Chinese Gen Z Consumers. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thach, E.C.; Olsen, J.E. Market Segment Analysis to Target Young Adult Wine Drinkers. Agribusiness 2006, 22, 307–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Alcohol Drink Association; JD Research. 2023 Alcohol Consumption Trend Report. 2023. Available online: https://www.linkbesttech.cn/jdr/2023_Online_Alcohol_Consumption_Trend_Report.pdf (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Hu, Y. The Market Structure of Chinese Wine Industry. Master’s Thesis, Chinese Agriculture University, Beijing, China, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Jenster, P.; Cheng, Y. Dragon Wine: Developments in the Chinese Wine Industry. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2008, 20, 244–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Wang, H.H. Market Power in the Chinese Wine Industry. Agribusiness 2017, 33, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Jian, Z. Analysis and Countermeasures to Industry Status of Chinese Wine. Liquor Mak. 2016, 48, 13–17. [Google Scholar]

- Capitello, R.; Agnoli, L.; Begalli, D. Chinese Import Demand for Wine: Evidence from Econometric Estimations. J. Wine Res. 2015, 26, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Bardají, I. A New Wine Superpower? An Analysis of the Chinese Wine Industry. Cah. Agric. 2017, 26, 65002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China General Administration of Customs. Customs Statistics. 2023. Available online: https://stats.customs.gov.cn/indexEn (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Zhao, Q.; Gan, S. Country Analysis and Development Trend of China’s Import Wine Market. China Brew. 2020, 39, 216–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, A. Social Influencers Hold the Key for Nz Wine Companies Eager to Enter the Asian Market. NZ Herald. 2019. Available online: https://www.nzherald.co.nz/business/social-influencers-hold-the-key-for-nz-wine-companies-eager-to-enter-the-asian-market/NWZSIU5LKXQI67CR5WGXWS6TOM/ (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Lu, L.; Chi, C.G.-Q.; Zou, R. Determinants of Chinese Consumers’ Organic Wine Purchase. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 3761–3778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Larimo, J.; Leonidou, L.C. Social Media in Marketing Research: Theoretical Bases, Methodological Aspects, and Thematic Focus. Psychol. Mark. 2023, 40, 124–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fountain, J.; Zhu, M. Young Chinese Consumers’ Wine Socialization, Current Wine Behavior and Perceptions of Wine. In The Wine Value Chain in China; Chandos Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 63–79. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Paladino, A. The Case of Wine: Understanding Chinese Gift-Giving Behavior. Mark. Lett. 2015, 26, 335–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidemann, V.; Atwal, G.; Heine, K. Chapter 4—Gift Culture in China: Consequences for the Fine Wine Sector. In The Wine Value Chain in China; Capitello, R., Charters, S., Menival, D., Yuan, J., Eds.; Chandos Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 47–61. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Y.; Wu, X.; Mu, W.; Fan, M.; Feng, J. Segmentation of Chinese Consumer Preference for Wine Extrinsic Attributes Based on Stratification and Weighted Clustering Algorithm. Food Res. Int. 2024, 196, 115097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, X.; Li, Y.; Xie, Y.; Tian, D.; Mu, W. Regional Difference Analyzing and Prediction Model Building for Chinese Wine Consumers’ Sensory Preference. Br. Food J. 2019, 122, 2587–2602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Murphy, J. A Qualitative Study of Chinese Wine Consumption and Purchasing: Implication for Australian Wine. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2007, 19, 98–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.-B.; McCarthy, B.; Chen, T.; Zhou, Z.-y.; Song, X.; Guo, S. Dynamics of Wine Consumption in China: An Empirical Study. In Proceedings of the 2013 27th Australian and New Zealand Academy of Management Conference: Managing on the Edge, Hobart, TAS, Australia, 1–23 December 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.; Sun, H.; Goodman, S.; Chen, S.; Ma, H. Chinese Choices: A Survey of Wine Consumers in Beijing. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2009, 21, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäufele, I.; Hamm, U. Consumers’ Perceptions, Preferences and Willingness-to-Pay for Wine with Sustainability Characteristics: A Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 147, 379–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Zeng, Y.C. Factors That Affect Willingness to Pay for Red Wines in China. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2014, 26, 426–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsi, A.M.; Modroño, J.I.; Mariel, P.; Cohen, J.; Lockshin, L. How Are Personal Values Related to Choice Drivers? An Application with Chinese Wine Consumers. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 86, 103989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockshin, L.; Corsi, A.M.; Cohen, J.; Lee, R.; Williamson, P. West Versus East: Measuring the Development of Chinese Wine Preferences. Food Qual. Prefer. 2017, 56, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnoli, L.; Capitello, R.; Begalli, D. Geographical Brand and Country-of-Origin Effects in the Chinese Wine Import Market. J. Brand Manag. 2014, 21, 541–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, A.; Leister, A.M.; McPhail, L.; Chen, W. The Evolution of Foreign Wine Demand in China. Aust. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2014, 58, 392–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmieri, N.; Maria, A.P.; Pesce, A. Young Consumers’ Preferences for Natural Wine: An Italian Exploratory Study. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2025, 37, 95–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazzani, C.; Maesano, G.; Begalli, D.; Capitello, R. Exploring the Effect of Naturalness on Consumer Wine Choices: Evidence from a Survey in Italy. Food Qual. Prefer. 2024, 113, 105062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorey, T.; Poutet, P. The Representations of Wine in France from Generation to Generation: A Dual Generation Gap. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2011, 13, 162–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorey, T.; Albouy, J. Perspective Générationnelle De La Consommation De Vin En France: Une Opportunité Pour La Segmentation. Décisions Mark. 2015, 79, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorey, T. The Success of Rosé Wine in France: The Millennial Revolution. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2021, 62, 357–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaud, D.A.; Lorey, T.; Pouzalgues, N.; Masson, G. The Effect of Rosé Wine Colors on Expected Flavor and Tastiness: A Cross-Modal Correspondence Explanation. Food Qual. Prefer. 2025, 123, 105308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellershohn, J.; Lumby, N.; Kozar, M. Label Design, Packaging, and the Canadian Millennial/Gen Z Wine Consumer. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2025, 28, 485–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiwachaleampong, R.; Maneekobkulwong, S.; Yimcharoen, P. An Empirical Study of Factors Influencing Behavioral Intention to Purchase Wine in Generation Y. In Proceedings of the 2022 7th International Conference on Business and Industrial Research (ICBIR), Bangkok, Thailand, 19–20 May 2022; pp. 573–576. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, R.; Bhanja, N. Consumer Preferences for Wine Attributes in an Emerging Market. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2018, 46, 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, A. Of Methods and Methodology. Qual. Res. Organ. Manag. Int. J. 2008, 3, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baran, S.J.; Davis, D.K. Mass Communication Theory, 7th ed.; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, J.; Plakoyiannaki, E.; Dimitratos, P.; Chen, S. The Qualitative Case Research in International Entrepreneurship: A State of the Art and Analysis. Int. Mark. Rev. 2019, 36, 164–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, D.; Shamdasani, P.; Rook, D. Focus Groups; SAGE Publications, Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, M.; Ozuem, W.; Howell, K.; Ranfagni, S. A Step-by-Step Process of Thematic Analysis to Develop a Conceptual Model in Qualitative Research. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2023, 22, 16094069231205789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Du, Y.; Morrish, S.C. Understanding the Wine Consumption Behaviour of Young Chinese Consumers. Beverages 2025, 11, 109. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages11040109

Du Y, Morrish SC. Understanding the Wine Consumption Behaviour of Young Chinese Consumers. Beverages. 2025; 11(4):109. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages11040109

Chicago/Turabian StyleDu, Yanni, and Sussie C. Morrish. 2025. "Understanding the Wine Consumption Behaviour of Young Chinese Consumers" Beverages 11, no. 4: 109. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages11040109

APA StyleDu, Y., & Morrish, S. C. (2025). Understanding the Wine Consumption Behaviour of Young Chinese Consumers. Beverages, 11(4), 109. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages11040109