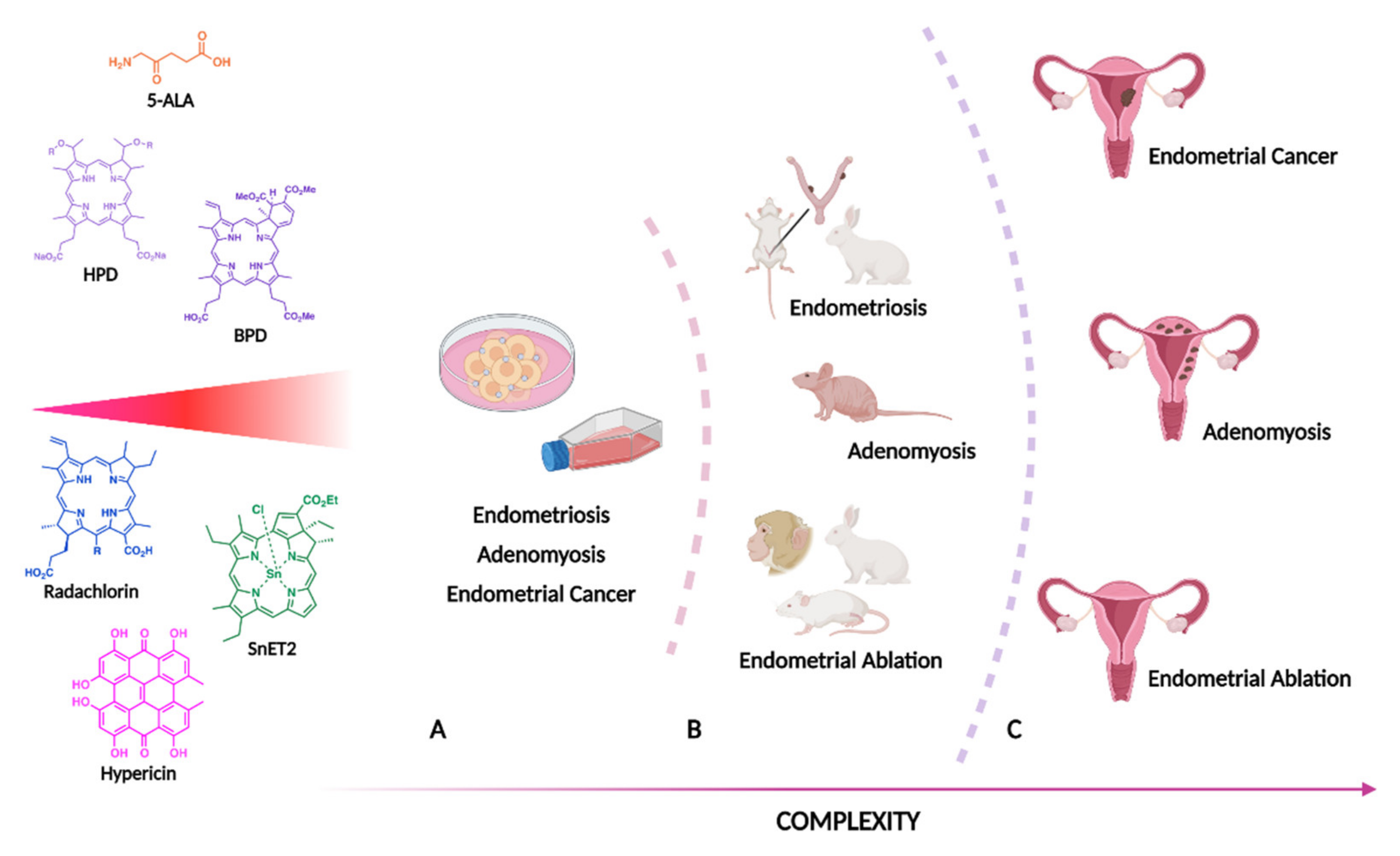

Applications of Photodynamic Therapy in Endometrial Diseases

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Endometrial Pathology

3.1. Endometrial Cancer

3.2. Endometriosis

3.3. Adenomyosis

3.4. Endometrial Ablation

4. Future Perspectives and Recommendations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Osuchowski, M.; Bartusik-Aebisher, D.; Osuchowski, F.; Aebisher, D. Photodynamic Therapy for Prostate Cancer—A Narrative Review. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2021, 33, 102158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EMA European Medicines Agency. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Roberts, J.E. Techniques to Improve Photodynamic Therapy. Photochem. Photobiol. 2020, 96, 524–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lan, M.; Zhao, S.; Liu, W.; Lee, C.S.; Zhang, W.; Wang, P. Photosensitizers for Photodynamic Therapy. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2019, 8, 1900132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwiatkowski, S.; Knap, B.; Przystupski, D.; Saczko, J.; Kędzierska, E.; Knap-Czop, K.; Kotlińska, J.; Michel, O.; Kotowski, K.; Kulbacka, J. Photodynamic Therapy—Mechanisms, Photosensitizers and Combinations. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 106, 1098–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Straten, D.; Mashayekhi, V.; de Bruijn, H.S.; Oliveira, S.; Robinson, D.J. Oncologic Photodynamic Therapy: Basic Principles, Current Clinical Status and Future Directions. Cancers 2017, 9, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostinis, P.; Berg, K.; Cengel, K.A.; Foster, T.H.; Girotti, A.W.; Gollnick, S.O.; Hahn, S.M.; Hamblin, M.R.; Juzeniene, A.; Kessel, D.; et al. Photodynamic Therapy of Cancer: An Update. CA. Cancer J. Clin. 2011, 61, 250–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calixto, G.; Bernegossi, J.; de Freitas, L.; Fontana, C.; Chorilli, M. Nanotechnology-Based Drug Delivery Systems for Photodynamic Therapy of Cancer: A Review. Molecules 2016, 21, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shishkova, N.; Kuznetsova, O.; Berezov, T. Photodynamic Therapy for Gynecological Diseases and Breast Cancer. Cancer Biol. Med. 2012, 9, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matoba, Y.; Banno, K.; Kisu, I.; Aoki, D. Clinical Application of Photodynamic Diagnosis and Photodynamic Therapy for Gynecologic Malignant Diseases: A Review. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2018, 24, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, M.J.; Laranjo, M.; Abrantes, A.M.; Torgal, I.; Botelho, M.F.; Oliveira, C.F. Clinical Translation for Endometrial Cancer Stem Cells Hypothesis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2015, 34, 401–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lõhmussaar, K.; Boretto, M.; Clevers, H. Human-Derived Model Systems in Gynecological Cancer Research. Trends Cancer 2020, 6, 1031–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Jemal, A. Cancer Statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2020, 70, 7–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Concin, N.; Creutzberg, C.L.; Vergote, I.; Cibula, D.; Mirza, M.R.; Marnitz, S.; Ledermann, J.A.; Bosse, T.; Chargari, C.; Fagotti, A.; et al. ESGO/ESTRO/ESP Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Endometrial Carcinoma. Virchows Arch. 2021, 478, 153–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obermair, A.; Baxter, E.; Brennan, D.J.; McAlpine, J.N.; Muellerer, J.J.; Amant, F.; van Gent, M.D.J.M.; Coleman, R.L.; Westin, S.N.; Yates, M.S.; et al. Fertility-Sparing Treatment in Early Endometrial Cancer: Current State and Future Strategies. Obstet. Gynecol. Sci. 2020, 63, 417–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-M.; Rhee, Y.-H.; Kim, J.-S. The Anticancer Effects of Radachlorin-Mediated Photodynamic Therapy in the Human Endometrial Adenocarcinoma Cell Line HEC-1-A. Anticancer Res. 2017, 37, 6251–6258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, J.; Carr, C.; Yao, M.; Radeva, M.; Priyadarshini, A.; Marquard, J.; Michener, C.M.; AlHilli, M. Endometrial Cancer in Young Women: Prognostic Factors and Treatment Outcomes in Women Aged ≤40 Years. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2020, 30, 631–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, N.; Creutzberg, C.; Amant, F.; Bosse, T.; González-Martín, A.; Ledermann, J.; Marth, C.; Nout, R.; Querleu, D.; Mirza, M.R.; et al. ESMO-ESGO-ESTRO Consensus Conference on Endometrial Cancer: Diagnosis, Treatment and Follow-Up. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2016, 26, 2–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzon, S.; Uccella, S.; Zorzato, P.C.; Bosco, M.; Franchi, M.P.; Student, V.; Mariani, A. Fertility-Sparing Management for Endometrial Cancer: Review of the Literature. Minerva Med. 2021, 112, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolun-Cholewa, M.; Butowska, W.; Fischer, N.; Warcho, W.; Nowak-Markwitz, E. 5-Aminolevulinic Acid–Mediated Photodynamic Therapy of Human Endometriotic Primary Epithelial Cells. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2009, 27, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raab, G.H.; Schneider, A.F.; Eiermann, W.; Gottschalk-Deponte, H.; Baumgartner, R.; Beyer, W. Response of Human Endometrium and Ovarian Carcinoma Cell-Lines to Photodynamic Therapy. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 1990, 248, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider-Yin, X.; Kurmanaviciene, A.; Roth, M.; Roos, M.; Fedier, A.; Minder, E.I.; Walt, H. Hypericin and 5-Aminolevulinic Acid-Induced Protoporphyrin IX Induce Enhanced Phototoxicity in Human Endometrial Cancer Cells with Non-Coherent White Light. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2009, 6, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.; Chang, J.-E.; Jheon, S.; Han, S.-J.; Kim, J.-K. Enhanced Production of Reactive Oxygen Species in HeLa Cells under Concurrent Low-dose Carboplatin and Photofrin Photodynamic Therapy. Oncol. Rep. 2018, 40, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varriale, L.; Coppola, E.; Quarto, M.; Maria Veneziani, B.; Palumbo, G. Molecular Aspects of Photodynamic Therapy: Low Energy Pre-Sensitization of Hypericin-Loaded Human Endometrial Carcinoma Cells Enhances Photo-Tolerance, Alters Gene Expression and Affects the Cell Cycle. FEBS Lett. 2002, 512, 287–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziółkowski, P.; Symonowicz, K.; Osiecka, B.J.; Rabczyński, J.; Gerber, J. Photodynamic Treatment of Epithelial Tissue Derived from Patients with Endometrial Cancer: A Contribution to the Role of Laminin and Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor in Photodynamic Therapy. J. Biomed. Opt. 1999, 4, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Bae, S.-M.; Kim, Y.-W.; Lee, J.-M.; Namkoong, S.-E.; Han, S.-J.; Kim, J.-K.; Lee, C.-H.; Chun, H.-J.; Jin, H.-S.; Ahn, W.-S. Photodynamic Effects of Radachlorin® on Cervical Cancer Cells. Cancer Res. Treat. 2004, 36, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dougherty, T.J.; Kaufman, J.E.; Goldfarb, A.; Weishaupt, K.R.; Boyle, D.; Mittleman, A. Photoradiation Therapy for the Treatment of Malignant Tumors. Cancer Res. 1978, 38, 2628–2635. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Corti, L.; Mazzarotto, R.; Belfontali, S.; De Luca, C.; Baiocchi, C.; Boso, C.; Calzavara, F. Gynecologic Cancer Recurrences and Photodynamic Therapy: Our Experience. J. Clin. Laser Med. Surg. 1995, 13, 325–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koren, H.; Alth, G. Photodynamic Therapy in Gynaecologic Cancer. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 1996, 36, 189–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wołuń-Cholewa, M.; Szymanowski, K.; Andrusiewicz, M.; Warchoł, W. Studies on Function of P-Glycoprotein in Photodynamic Therapy of Endometriosis. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2010, 28, 735–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wołuń-Cholewa, M.; Szymanowski, K.; Nowak-Markwitz, E.; Warchoł, W. Photodiagnosis and Photodynamic Therapy of Endometriotic Epithelial Cells Using 5-Aminolevulinic Acid and Steroids. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2011, 8, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki-Kakisaka, H.; Murakami, T.; Hirano, T.; Terada, Y.; Yaegashi, N.; Okamura, K. Selective Accumulation of PpIX and Photodynamic Effect after Aminolevulinic Acid Treatment of Human Adenomyosis Xenografts in Nude Mice. Fertil. Steril. 2008, 90, 1523–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovacevic, N. Surgical Treatment and Fertility Perservation in Endometrial Cancer. Radiol. Oncol. 2021, 55, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucchini, S.M.; Esteban, A.; Nigra, M.A.; Palacios, A.T.; Alzate-Granados, J.P.; Borla, H.F. Updates on Conservative Management of Endometrial Cancer in Patients Younger than 45 Years. Gynecol. Oncol. 2021, 161, 802–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pujade-Lauraine, E.; Hilpert, F.; Weber, B.; Reuss, A.; Poveda, A.; Kristensen, G.; Sorio, R.; Vergote, I.; Witteveen, P.; Bamias, A.; et al. Bevacizumab Combined With Chemotherapy for Platinum-Resistant Recurrent Ovarian Cancer: The AURELIA Open-Label Randomized Phase III Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 1302–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sourouni, M.; Kiesel, L. Hormone Replacement Therapy After Gynaecological Malignancies: A Review Article. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2021, 81, 549–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atallah, D.; El Kassis, N.; Safi, J.; El Hachem, H.; Chahine, G.; Moubarak, M. The Use of Hysteroscopic Endometrectomy in the Conservative Treatment of Early Endometrial Cancer and Atypical Hyperplasia in Fertile Women. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2021, 304, 1299–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixo, R.; Laranjo, M.; Abrantes, A.M.; Brites, G.; Serra, A.; Proença, R.; Botelho, M.F. Retinoblastoma: Might Photodynamic Therapy Be an Option? Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2015, 34, 563–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laranjo, M.; Aguiar, M.C.; Pereira, N.A.M.; Brites, G.; Nascimento, B.F.O.; Brito, A.F.; Casalta-Lopes, J.; Gonçalves, A.C.; Sarmento-Ribeiro, A.B.; Pineiro, M.; et al. Platinum(II) Ring-Fused Chlorins as Efficient Theranostic Agents: Dyes for Tumor-Imaging and Photodynamic Therapy of Cancer. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 200, 112468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, M.C.; Jung, S.G.; Park, H.; Cho, Y.H.; Lee, C.; Kim, S.J. Fertility Preservation via Photodynamic Therapy in Young Patients with Early-Stage Uterine Endometrial Cancer: A Long-Term Follow-up Study. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2013, 23, 698–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, M.C.; Kim, G.; Hwang, Y.Y. Fertility-Sparing Management Combined with Photodynamic Therapy for Endometrial Stromal Sarcoma: A Case Report. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2014, 11, 533–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zondervan, K.T.; Becker, C.M.; Missmer, S.A. Endometriosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1244–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 11: Medical Management of Endometriosis. Obstet. Gynecol. 1999, 94, 1–14.

- Dunselman, G.A.J.; Vermeulen, N.; Becker, C.; Calhaz-Jorge, C.; D’Hooghe, T.; De Bie, B.; Heikinheimo, O.; Horne, A.W.; Kiesel, L.; Nap, A.; et al. ESHRE Guideline: Management of Women with Endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. 2014, 29, 400–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinsdale, N.; Nepomnaschy, P.; Crespi, B. The Evolutionary Biology of Endometriosis. Evol. Med. Public Health 2021, 9, 174–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrucco, O.M.; Sathananden, M.; Petrucco, M.F.; Knowles, S.; McKenzie, L.; Forbes, I.J.; Cowled, P.A.; Keye, W.E. Ablation of Endometriotic Implants in Rabbits by Hematoporphyrin Derivative Photoradiation Therapy Using the Gold Vapor Laser. Lasers Surg. Med. 1990, 10, 344–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manyak, M.J.; Nelson, L.M.; Solomon, D.; Russo, A.; Thomas, G.F.; Stillman, R.J. Photodynamic Therapy of Rabbit Endometrial Transplants: A Model for Treatment of Endometriosis. Fertil. Steril. 1989, 52, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzemien, A.A.; Van Vugt, D.A.; Fletcher, W.A.; Reid, R.L. Effectiveness of Photodynamic Ablation for Destruction of Endometrial Explants in a Rat Endometriosis Model. Fertil. Steril. 2002, 78, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.Z.; Van Dijk-Smith, J.P.; Van Vugt, D.A.; Kennedy, J.C.; Reid, R.L. Fluorescence and Photosensitization of Experimental Endometriosis in the Rat after Systemic 5-Aminolevulinic Acid Administration: A Potential New Approach to the Diagnosis and Treatment of Endometriosis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1996, 174, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szubert, M.; Koziróg, E.; Olszak, O.; Krygier-Kurz, K.; Kazmierczak, J.; Wilczynski, J. Adenomyosis and Infertility—Review of Medical and Surgical Approaches. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uterine Artery Embolisation for Treating Adenomyosis Interventional Procedures Guidance [IPG473]. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ipg473 (accessed on 13 April 2021).

- Suzukikakisaka, H.; Murakami, T.; Hirano, T.; Terada, Y.; Yaegashi, N.; Okamura, K. Effects of Photodynamic Therapy Using 5-Aminolevulinic Acid on Cultured Human Adenomyosis-Derived Cells. Fertil. Steril. 2007, 87, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatta, N.; Anderson, R.R.; Flotte, T.; Schiff, I.; Hasan, T.; Nishioka, N.S. Endometrial Ablation by Means of Photodynamic Therapy with Photofrin II. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1992, 167, 1856–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.Z.; Van Vugt, D.A.; Kennedy, J.C.; Reid, R.L. Evidence of Lasting Functional Destruction of the Rat En Dometrium after 5-Aminolevulinic Acid—Induced Photodynamic Ablation: Prevention of Implantation. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1993, 168, 995–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyss, P.; Tadir, Y.; Tromberg, B.J.; Liaw, L.; Krasieva, T.; Berns, M.W. Benzoporphyrin Derivative: A Potent Photosensitizer for Photodynamic Destruction of Rabbit Endometrium. Obstet. Gynecol. 1994, 84, 409–414. [Google Scholar]

- Wyss, P.; Tromberg, B.J.; Wyss, M.T.; Krasieva, T.; Schell, M.; Berns, M.W.; Tadir, Y. Photodynamic Destruction of Endometrial Tissue with Topical 5-Aminolevulinic Acid in Rats and Rabbits. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1994, 171, 1176–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Steiner, R.A.; Tadir, Y.; Tromberg, B.J.; Krasieva, T.; Ghazains, A.T.; Wyss, P.; Berns, M.W. Photosensitization of the Rat Endometrium Following 5-Aminolevulinic Acid Induced Photodynamic Therapy. Lasers Surg. Med. 1996, 18, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, R.A.; Tromberg, B.J.; Wyss, P.; Krasieva, T.; Chandanani, N.; McCullough, J.; Berns, M.W.; Tadir, Y. Rat Reproductive Performance Following Photodynamic Therapy with Topically Administered Photofrin. Hum. Reprod. 1995, 10, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Fehr, M.K.; Madsen, S.J.; Svaasand, L.O.; Tromberg, B.J.; Eusebio, J.; Berns, M.W.; Tadir, Y. Intrauterine Light Delivery for Photodynamic Therapy of the Human Endometrium. Hum. Reprod. 1995, 10, 3067–3072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mhawech, P. High Efficacy of Photodynamic Therapy on Rat Endometrium after Systemic Administration of Benzoporphyrin Derivative Monoacid Ring A. Hum. Reprod. 2003, 18, 1707–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzemien, A.A.; Van Vugt, D.A.; Pottier, R.H.; Dickson, E.F.; Reid, R.L. Evaluation of Novel Nonlaser Light Source for Endometrial Ablation Using 5-Aminolevulinic Acid. Lasers Surg. Med. 1999, 25, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocklin, G.B.; Kelly, H.G.; Anderson, S.C.; Edwards, L.E.; Gimpelson, R.J.; Perez, R.E. Photodynamic Therapy of Rat Endometrium Sensitized with Tin Ethyl Etiopurpurin. J. Am. Assoc. Gynecol. Laparosc. 1996, 3, 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Vugt, D. Photodynamic Endometrial Ablation in the Nonhuman Primate. J. Soc. Gynecol. Investig. 2000, 7, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyss, P.; Steiner, R.; Liaw, L.H.; Wyss, M.T.; Ghazarians, A.; Berns, M.W.; Tromberg, B.J.; Tadir, Y. Uterus and Endometrium: Regeneration Processes in Rabbit Endometrium: A Photodynamic Therapy Model. Hum. Reprod. 1996, 11, 1992–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matoba, Y.; Banno, K.; Kobayashi, Y.; Kisu, I.; Aoki, D. Atypical Polypoid Adenomyoma Treated by Hysteroscopy with Photodynamic Diagnosis Using 5-Aminolevulinic Acid: A Case Report. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2019, 27, 295–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osada, H. Uterine Adenomyosis and Adenomyoma: The Surgical Approach. Fertil. Steril. 2018, 109, 406–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minalt, N.; Canela, C.D.; Marino, S. Endometrial Ablation; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459245/ (accessed on 26 April 2022).

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Heavy Menstrual Bleeding: Assessment and Management NICE Guideline [NG88]; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wyss, P.; Svaasand, L.O.; Tadir, Y.; Haller, U.; Berns, M.W.; Wyss, M.T.; Tromberg, B.J. Photomedicine of the Endometrium: Experimental Concepts. Hum. Reprod. 1995, 10, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wyss, P.; Fehr, M.; Van den Bergh, H.; Haller, U. Feasibility of Photodynamic Endometrial Ablation without Anesthesia. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 1998, 60, 287–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyss, P.; Caduff, R.; Tadir, Y.; Degen, A.; Wagnières, G.; Schwarz, V.; Haller, U.; Fehr, M. Photodynamic Endometrial Ablation: Morphological Study. Lasers Surg. Med. 2003, 32, 305–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degen, A.F.; Gabrecht, T.; Mosimann, L.; Fehr, M.K.; Hornung, R.; Schwarz, V.A.; Tadir, Y.; Steiner, R.A.; Wagnières, G.; Wyss, P. Photodynamic Endometrial Ablation for the Treatment of Dysfunctional Uterine Bleeding: A Preliminary Report. Lasers Surg. Med. 2004, 34, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gannon, M.J.; Brown, S.B. Photodynamic Therapy and Its Applications in Gynaecology. BJOG An Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 1999, 106, 1246–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gannon, M.J.; Johnson, N.; Roberts, D.J.H.; Holroyd, J.A.; Vernon, D.I.; Brown, S.B.; Lilford, R.J. Photosensitization of the Endometrium with Topical 5-Aminolevulinic Acid. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1995, 173, 1826–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehr, M.K.; Wyss, P.; Tromberg, B.J.; Krasieva, T.; DiSaia, P.J.; Lin, F.; Tadir, Y. Selective Photosensitizer Localization in the Human Endometrium after Intrauterine Application of 5-Aminolevulinic Acid. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1996, 175, 1253–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panngom, K.; Baik, K.Y.; Nam, M.K.; Han, J.H.; Rhim, H.; Choi, E.H. Preferential Killing of Human Lung Cancer Cell Lines with Mitochondrial Dysfunction by Nonthermal Dielectric Barrier Discharge Plasma. Cell Death Dis. 2013, 4, e642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hornung, R.; Fehr, M.K.; Tromberg, B.J.; Major, A.; Krasieva, T.B.; Berns, M.W.; Tadir, Y. Uptake of the Photosensitizer Benzoporphyrin Derivative in Human Endometrium after Topical Application in Vivo. J. Am. Assoc. Gynecol. Laparosc. 1998, 5, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadir, Y.; Hornung, R.; Pham, T.H.; Tromberg, B.J. Intrauterine light probe for photodynamic ablation therapy. Obstet. Gynecol. 1999, 93, 299–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demazeau, M.; Gibot, L.; Mingotaud, A.-F.; Vicendo, P.; Roux, C.; Lonetti, B. Rational Design of Block Copolymer Self-Assemblies in Photodynamic Therapy. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2020, 11, 180–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Jo, Y.-U.; Na, K. Photodynamic Therapy with Smart Nanomedicine. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2020, 43, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, C.-Y.; Wang, P.-T.; Su, W.-C.; Teng, H.; Huang, W.-L. Nanomedicine-Based Strategies Assisting Photodynamic Therapy for Hypoxic Tumors: State-of-the-Art Approaches and Emerging Trends. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thangudu, S.; Su, C.-H. Peroxidase Mimetic Nanozymes in Cancer Phototherapy: Progress and Perspectives. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallidi, S.; Anbil, S.; Bulin, A.-L.; Obaid, G.; Ichikawa, M.; Hasan, T. Beyond the Barriers of Light Penetration: Strategies, Perspectives and Possibilities for Photodynamic Therapy. Theranostics 2016, 6, 2458–2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, J.H.; Rodrigues, J.A.; Pimenta, S.; Dong, T.; Yang, Z. Photodynamic Therapy Review: Principles, Photosensitizers, Applications, and Future Directions. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, N.A.M.; Laranjo, M.; Nascimento, B.F.O.; Simões, J.C.S.; Pina, J.; Costa, B.D.P.; Brites, G.; Braz, J.; Seixas de Melo, J.S.; Pineiro, M.; et al. Novel Fluorinated Ring-Fused Chlorins as Promising PDT Agents against Melanoma and Esophagus Cancer. RSC Med. Chem. 2021, 12, 615–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nascimento, B.F.O.; Laranjo, M.; Pereira, N.A.M.; Dias-Ferreira, J.; Piñeiro, M.; Botelho, M.F.; Pinho e Melo, T.M.V.D. Ring-Fused Diphenylchlorins as Potent Photosensitizers for Photodynamic Therapy Applications: In Vitro Tumor Cell Biology and in Vivo Chick Embryo Chorioallantoic Membrane Studies. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 17244–17250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, N.A.M.; Laranjo, M.; Pina, J.; Oliveira, A.S.R.; Ferreira, J.D.; Sánchez-Sánchez, C.; Casalta-Lopes, J.; Gonçalves, A.C.; Sarmento-Ribeiro, A.B.; Piñeiro, M.; et al. Advances on Photodynamic Therapy of Melanoma through Novel Ring-Fused 5,15-Diphenylchlorins. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 146, 395–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, N.A.M.; Laranjo, M.; Casalta-Lopes, J.; Serra, A.C.; Piñeiro, M.; Pina, J.; Seixas de Melo, J.S.; Senge, M.O.; Botelho, M.F.; Martelo, L.; et al. Platinum(II) Ring-Fused Chlorins as Near-Infrared Emitting Oxygen Sensors and Photodynamic Agents. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2017, 8, 310–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunaydin, G.; Gedik, M.E.; Ayan, S. Photodynamic Therapy for the Treatment and Diagnosis of Cancer–A Review of the Current Clinical Status. Front. Chem. 2021, 9, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bochenek, K.; Aebisher, D.; Międzybrodzka, A.; Cieślar, G.; Kawczyk-Krupka, A. Methods for Bladder Cancer Diagnosis—The Role of Autofluorescence and Photodynamic Diagnosis. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2019, 27, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, Z. Pros, Cons and Future Prospects of ALA-Photodiagnosis, Phototherapy and Pharmacology in Cancer Therapy—A Mini Review. Photonics Lasers Med. 2015, 4, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjipanayis, C.G.; Stummer, W. 5-ALA and FDA Approval for Glioma Surgery. J. Neurooncol. 2019, 141, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadab, R.; Nerli, R.B.; Saziya, B.R.; Ghagane, S.C.; Shreya, C. 5-ALA-Induced Fluorescent Cytology in the Diagnosis of Bladder Cancer—A Preliminary Report. Indian J. Surg. Oncol. 2021, 12, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyss, P.; Degen, A.; Caduff, R.; Hornung, R.; Haller, U.; Fehr, M. Fluorescence Hysteroscopy Using 5-Aminolevulinic: A Descriptive Study. Lasers Surg. Med. 2003, 33, 209–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matoba, Y.; Banno, K.; Kisu, I.; Tsuji, K.; Aoki, D. Atypical Endometrial Hyperplasia Diagnosed by Hysteroscopic Photodynamic Diagnosis Using 5-Aminolevulinic Acid. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2019, 26, 45–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matoba, Y.; Banno, K.; Kobayashi, Y.; Yamagami, W.; Nakamura, M.; Kisu, I.; Aoki, D. Hysteroscopic Treatment Assisted by Photodynamic Diagnosis for Atypical Polypoid Adenomyoma: A Report of Two Cases. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2021, 36, 102583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, M.J.; Laranjo, M.; Abrantes, A.M.; Casalta-Lopes, J.; Sarmento-Santos, D.; Costa, T.; Serambeque, B.; Almeida, N.; Gonçalves, T.; Mamede, C.; et al. Endometrial Cancer Spheres Show Cancer Stem Cells Phenotype and Preference for Oxidative Metabolism. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2019, 25, 1163–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laranjo, M.; Carvalho, M.J.; Serambeque, B.; Alves, A.; Marto, C.M.; Silva, I.; Paiva, A.; Botelho, M.F. Obtaining Cancer Stem Cell Spheres from Gynecological and Breast Cancer Tumors. JoVE—J. Vis. Exp. 2020, 157, e60022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Md, S.; Haque, S.; Madheswaran, T.; Zeeshan, F.; Meka, V.S.; Radhakrishnan, A.K.; Kesharwani, P. Lipid Based Nanocarriers System for Topical Delivery of Photosensitizers. Drug Discov. Today 2017, 22, 1274–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, K.; Khachemoune, A. An Update on Topical Photodynamic Therapy for Clinical Dermatologists. J. Dermatolog. Treat. 2019, 30, 732–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ref. | Disease, Model | PDT | Methods | Main Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [21] | Endometrial carcinoma, HEC1-1A cell line | PS: HPD, 1.25–80 µg/mL DLI: 12–72 h Light: 630 nm 40–100 mW/cm2, up to 20 J/cm2 NT: single | Cell viability | The photosensitiser per se did not cause any changes. PDT led to the loss of viability, with complete cell death for the more potent treatments. |

| [23] | Cervical or endometrial cancer, Hela cell line | PS: HPD (Photofrin), 20 µM DLI: 3 h Light: 2.5 mW/cm2 630 nm, up to 3.3 mJ NT: single | ROS levels assessment (fluorimetry); Apoptosis/necrosis assay (confocal microscopy); MTT assay | While hydroxyl radical and superoxide anion concentrations remained stable after PDT, a slight increase in hydrogen peroxide was observed. When PDT was combined with carboplatin, ROS concentrations raised. PDT increased necrotic cells while PDT combined with carboplatin increased apoptotic and necrotic cells. The viability of cells submitted to PDT was dependent on the light energy deposited. Association with carboplatin showed better outcomes when low light energies (330–660 mJ) were used. |

| [25] | Endometrial cancer; primary cells, 10 cases | PS: HPD, 0.1 mg/L DLI: 24 h Light: 620–640 nm 18 J/cm2 75 mW NT: single | Immunohistochemistry (H&E, laminin, EGFR, nucleolar organised regions staining) | PDT induced no damage to the basal membrane (laminin) but decreased EGFR and proliferation, while enhancement of necrosis was observed. |

| [24] | Endometrial carcinoma, HEC-1B cell line | PS: Hypericin, 0.15 µM DLI: 16 h Light: 599 nm 2–10 J/cm2; 599 nm 2 + 5 J/cm2 spaced 3 or 20 h NT: Single or double irradiation spaced of 3 or 20 h | Cell photosensitisation; Cell uptake; Cell cycle (FACS); Western blot | PARP activation determined apoptotic cell death, while necrosis was observed for higher fluences. Hypericin uptake remained quite steady from 3 to 20 h. Sub-cellular fractions showed a tendency for nuclear accumulation. Photoactivation stimulated HSP70 synthesis, P21 and P53 expression. The cell cycle seemed to accumulate in the G2/M phase. |

| [20] | Endometriosis; primary epithelial cells from endometriotic foci, 15 cases | PS: 5-ALA, 1–8 mM DLI: 2 and 4 h Light: 30 mW 56 J/cm2 635 nm; electric bulb (75 W) NT: single | PpIX uptake; Cell death; Rhodamine 123 staining | Accumulation of PpIX was mostly noted after two hours of 5-ALA incubation. Laser irradiation resulted in gradually rising apoptotic cells. |

| [22] | Endometrial carcinoma, HEC1-1A cell line | PS: 5-ALA, 0.5 mM; hypericin, 60 nM; 5-ALA + hypericin DLI: 4 h Light: 2.5 J/cm2 635 nm or 400–800 nm NT: single | Clonogenic assay; HPLC PpIX quantification | 5-ALA PDT decreased cell survival. No enhancement was seen by combining 5-ALA with hypericin after 635 nM irradiation. A sight additive effect was observed if irradiation was made with white light. 5-ALA was superior to hypericin in the conditions tested. |

| [30] | Endometriosis; primary epithelial cells from eutopic (normal) and ectopic endometria, 8 and 15 cases, respectively | PS: 5-ALA, 1–8 mM DLI: 2 h Light: 56 J/cm2 635 nm NT: single | Blocking P-GP using verapamil; XTT Assay; Immunohistochemistry | Endometriotic cells were significantly more responsive to PDT than normal endometrium. PDT caused significant cell growth inhibition, which was potentiated by association with a PGP inhibitor (verapamil). |

| [31] | Endometriosis; primary epithelial cells from eutopic (normal) and ectopic endometria, 15 cases each | PS: 5-ALA (PpIX), 2.0 mM DLI: 2 h Light: 30 mW/cm2 635 nm NT: single | PpIX uptake (confocal microscopy); XTT assay | Normal and endometriotic cells accumulate PpIX, which increases after hormonal stimulation. Endometriotic cells were significantly more responsive to PDT than normal endometrium. |

| [32] | Adenomyosis; primary cells from adenomyosis and endometrium | PS: 5-ALA, 100 mg/mL DLI: 8, 24 and 48 h Light: 635 nm NT: single | Immunocytochemistry; MTT assay | Loss of cell viability, dependent on the 5-ALA incubation time and irradiation. Adenomyosis cells were more susceptible to PDT than stromal cells. |

| [16] | Endometrial carcinoma, HEC-1-A cell line | PS: Radachlorin, 2.5–200 µM DLI: 4 h Light: 50 mW 660 nm, until 25 J/cm2 NT: single | Morphology (microscopy); MTT assay; TUNEL assay, Tube formation assay; Invasion assay; Prostaglandin E2 assay; Western Blot | PDT treated cells showed condensed cytoplasm or floating growth patterns. IC50 of 55.4 µM and 20 µM were obtained 24 and 48 h after PDT, respectively. Annexin-V-positive and TUNEL-positive cells increased after PDT treatment, mostly after 48 h. PARP and caspase 9 increased when PDT was combined with VEGF treatment. PDT reduced tubular formation, and PDT + VEGF conditions led to more robust inhibition of tubular formation. PDT (and PDT combined with VEGF) suppressed the invasion. PDT (and PDT combined with VEGF) reduced prostaglandin 2 production. PDT combined with VEGF reduced EGFR, VEGFR2 and RhoA expression. |

| Ref. | Disease/Intervention | Species | PDT | Methodology | Main Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [46] | Endometriosis | Sp.: New Zealand white rabbits Md.: Peritoneal autotransplantation of endometrial tissu n.: 10 rabbits | PS: HPD, iv., 50 mg/kg DLI: 24 h Light: iu., 627.8 nM, 0.5–1.3 W/cm2, up to 100 J/cm2 | Bioavailability (fluorescence); Histopathology | Endometriotic lesions show higher HPD fluorescence. PDT lead to tissue damage, namely necrosis and hyperaemia, with preservation of the surrounding tissues. |

| [47] | Endometriosis | Sp.: New Zealand white rabbits Md.: Peritoneal autotransplantation of endometrial tissue n.: 15 rabbits (virgin) | PS: HPD, iv., 10 mg/kg DLI: 24 h Light: iu., 630 nm, 100–210 mW/cm2; up to 50 or 100 J/cm2 | Histopathology | 81% and 60% of the transplants treated with 100 J/cm2 and 50 J/cm2 presented complete or almost complete endometrial epithelial destruction, respectively. |

| [48] | Endometriosis | Sp.: Sprague-Dawley rats Md.: Peritoneal autotransplantation of endometrial tissue n.: 38 rats (mature) | PS: 5-ALA, iv., 100 and 400 mg/kg DLI: 3 h Light: ip. (surgical), 600–700 nm 340 ± 20 mW; 5–15 min | Histopathology | Endometrial ablation of all explants collected 3 to 4 days after PDT, and absence of regrowth after three weeks. Peritoneal necrosis recovered after 16 days. |

| [32] | Adenomyosis | Sp.: Immunodeficient nude mice Md.: Transplantation of human adenomyosis tissues in ovariectomised animals. (Oestradiol transdermal administration.) n.: 8 6–8 weeks mice (mature) | PS: 5-ALA, ip., 0.8 g/kg DLI: 3 h Light: ip., 630 nm, 100 mW | Bioavailability (fluorescence); Histopathology | Higher fluorescence was detected in adenomyosis tissues than in myometrium, with a maximum 3 h after administration. A decrease in the number of epithelial and particularly stromal cells was observed in adenomyosis tissues after PDT. No necrotic cells were observed. |

| [53] | Endometrial ablation | Sp.: New Zealand white rabbits Md.: n.a. n.: 58 rabbits (virgin) | PS: Photofrin II, iv., 0–10 mg/kg DLI: 4, 24 and 48 h Light: iu., 630 nm, 100–200 J/cm2 | Bioavailability (fluorescence and microscopy); Histopathology | Bioavailability in the endometrium was up to 4 times higher than in the myometrium. For endometrial ablation, PS doses of 1–2 mg/kg and 100 J/cm2 showed to be appropriate, with preservation of surrounding organs. PDT resulted in extensive haemorrhage and cell death 24 h after treatment and necrosis five days later. |

| [54] | Endometrial ablation | Sp.: Sprague-Dawley rats Md.: n.a. n.: 51 + 24 rats (mature) | PS: 5-ALA, iu., 4–16 mg DLI: 3 h Light: iu., red light, 150 J/cm2, 30 min | Short- and long-term outcomes (10 and 60 days); Implantation rate; Histopathology | PDT ablation decreased implantation rate and endometrial atrophy. |

| [55] | Endometrial ablation | Sp.: New Zealand white rabbits Md.: n.a. n.: 18 rabbits (mature) | PS: BDP, iu., 2 mg DLI: 1.5 h Light: iu., 690 nm, 195 mW, 40–80 J/cm2 | Bioavailability (fluorescence); Histopathology (optical and SEM) | Glandular fluorescence was superior to stroma and myometrium. The maximum fluorescence was noticed 1.5 h after administration. The histological study showed endometrial epithelium destruction after treatment with minimal regeneration. |

| [56] | Endometrial ablation | Sp.: Sprague-Dawley rats and New Zealand white rabbits Md.: n.a. n.: 12 rats (mature) and 42 rabbits (mature) | PS: 5-ALA, iu., up to 480 mg DLI: 3 h Light: iu., 630 nm 255 mW, 80–160 J/cm2 | Bioavailability (fluorescence); Histopathology (optical and SEM) | The maximum fluorescence of protoporphyrin IX was reached 3 h after administration, proving higher in the glands. Epithelial destruction was observed in the histological studies, revealing a low regeneration. |

| [57] | Endometrial ablation | Sp.: Sprague-Dawley rats Md.: n.a. n.: 87 rats (mature) | PS: 5-ALA, iu., 58 mg/kg DLI: 3 h Light: iu., 630 nm, 133 mW/cm2 up to 212 J/cm2 (100 J/cm2 for the photosensitivity study) | Bioavailability (fluorescence); Implantation rate; Skin photosensitivity; Thermogenic effect; Histopathology | The fluorescence study revealed a higher photosensitiser concentration in the glands 3 to 6 h after administration. Endometrial destruction with atrophy was observed 7 to 10 weeks after PDT. The number of implantations was significantly lower in treated horns. |

| [58] | Endometrial ablation | Sp.: Sprague-Dawley rats Md.: n.a. n.: 74 rats (mature) | PS: HPD (Photofrin), iu., 0.7 mg/kg DLI: 3, 24 and 72 h Light: iu., 630 nm, 100 mW/cm2 up to 80 J/cm2 (200 mW/cm2 up to 100 J/cm2 for the photosensitivity study) | Bioavailability (fluorescence); Implantation rate; Skin photosensitivity | Photofrin diffusely distributed along the endometrium and myometrium. A significant reduction in implantations was observed in PDT treated horns. No skin photosensitivity was noticed. |

| [59] | Endometrial ablation | Sp.: Sprague-Dawley rats Md.: n.a. n.: 125 rats (mature) | PS: 5-ALA, iu., 30 mg DLI: 3 h Light: iu., 630 nm, 100 mW/cm2; ranging 8–160 J/cm2 | Histopathology; Thermogenic effect; Implantation rate | Temperatures never exceeded 40 °C during PDT. Endometrial outcomes varied with light fluency. The deposition of 43 J/cm2 led to endometrial stroma and myometrium damage with regeneration within three weeks. Higher intensity of 64 J/cm2 determined irreversible endometrial destruction. A reduced number of implantations was observed after PDT. |

| [60] | Endometrial ablation | Sp.: Sprague-Dawley rats Md.: n.a. n.: 32 rats | PS: BPD, iv., 0.0625–2 mg/kg DLI: 5 min Light: iu., 630 nm 100 mW/cm, until 120 J/cm2 | Histopathology | Endometrial destruction was observed in all treatment groups. The most significant degree of destruction was obtained at the higher dose of 2 mg/kg. Gland destruction and myometrium conservation were achieved with doses of 0.5 to 0.0625 mg/kg. |

| [61] | Endometrial ablation | Sp.: Sprague-Dawley rats Md.: n.a. n.: 30 rats (mature) | PS: 5-ALA, iu., 0.1 mL of 10 mg/mL solution DLI: 3 h Light: iu., 600–700 nm, 280 ± 40 mW, 180 J/cm2 (10 min) or 630 nm, 300 mW, 1080 J/cm2 (60 min) | Histopathology; Thermogenic effect | PDT resulted in extensive histologic damage to all layers of the uterine wall. Specimens were devoid of luminal epithelium and endometrial glands, while stromal oedema was prominent. Moreover, damage to the circular myometrium and focal necrosis throughout the longitudinal outer layer of the myometrium was evident. During irradiation, a temperature rise to 46 °C was observed. |

| [62] | Endometrial ablation | Sp.: Sprague-Dawley rats Md.: n.a. n.: 45 rats (8–10 weeks) | PS: SnET2, iv. (tail vein) or iu., 2 mg/kg (iv.) or 60 µg (iu.) DLI: 3 and 24 h Light: iu., 665 nm, 100 mW/cm2, up to 200 J/cm2 | Fluorescence detection; Histopathology | The fluorescence study revealed the highest levels of photosensitiser 3 h after administration. Effective endometrial ablation was observed through intrauterine administration of SnET2 at 150 J/cm2 with a DLI of 24 h. Necrosis extent was light-dose dependent. |

| [63] | Endometrial ablation | Sp.: Rhesus monkeys (and one cynomolgus monkey) Md.: n.a. n.: 18 + 1 monkeys, 5–20 years | PS: 5-ALA, iu., 250 mg/mL DLI: 4 h Light: iu., 635 nm 300 mW; 60 min (continuous or fractionated) | Histopathology; Thermogenic effect | Endometrial ablation was observed in all animals ranging from moderate to complete. The greatest degree was seen in menopausal monkeys. The luminal temperature increased up to 50 °C, whereas no significant increases were seen in light controls. |

| [64] | Endometrial ablation | Sp.: New Zealand white rabbits Md.: n.a. n.: 15 rabbits (mature) | PS: 5-ALA and BPD, iu., ALA: 2.4 g; BPD: 24 mg DLI: ALA: 3 h; BPD: 1.5 h Light: iu., ALA: 630 nm, 40–80 J/cm2; BPD: 690 nm, 40–80 J/cm2 | Histopathology (optical and SEM) | Endometrium regeneration was activated 24 h and completed 72 h after photodynamic ablation. Proliferation initiated in deeper regions of the glands. |

| Ref. | Disease | N | Age | PDT | Follow Up | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [27] | Endometrial carcinoma, metastatic | 1 | n.d. | PS: HPD, 5 mg/kg, iv. DLI: unclear Light: 600–700 nM, 100 mW/cm2 | n.d. | Complete response in six tumour sites. |

| [28] | Endometrial adenocarcinoma, recurrent | 5 | 67.5 years (median age) | PS: HPD, 5 mg/kg, iv. DLI: 48 h Light: 630 (and 514 nm in some cases), 60–500 J/cm2 | Up to 92 months | In the cases where PDT was used as palliative, absence of symptoms for at least 60 days was observed in 66,6% of the cases. In the curative intent, PDT complete response was achieved in 70,8%. Survival ranged from three to 92 months. Obs.: Avoidance of direct sunlight for 30 days. |

| [29] | Endometrial carcinoma, stage 1a | 7 | 60–81 years | PS: HPD, 2 mg/kg DLI: 24–72 h Light: 632 nm, 200 J/cm2 | 12 months | Despite five out of seven cases of initial (1 month) complete response, after one year, four patients relapsed. Obs.: Avoidance of direct sunlight for 38 days. |

| [76] | Endometrioid adenocarcinoma, grade 1 or 2 | 16 | 24–35 years | PS: HPD, 2 mg/kg, iv. DLI: 48 h Light: 630 nm, 600 mW, 900 seg | Up to 140 months | Complete response in 12 cases (75%) and 4 cases of recurrence. Among seven women who attempted to get pregnant, four had successful pregnancies. Adverse effects: four cases of reversible mild facial angioedema |

| [41] | Endometrial sarcoma, low grade | 1 | 31 years | PS: HPD, 3 mg/kg, iv. DLI: 48 h Light: 631 nm, 600 mW, 900 seg | 99 months | No evidence of recurrence during 99 months. After 32 months, an IVF was successful with the delivery of twins. Obs.: Adjuvant treatment with an aromatase inhibitor. |

| [70] | Abnormal uterine bleeding | 3 | n.d. | PS: 5-ALA, 1.5 mL, 400 mg/mL solution, iu. DLI: 4–6 h Light: 635 nm, 160 J/cm2 | Six months | Reduction of uterine bleeding. Normal endometrium and thinned endometrial layers lacking glands, evidence of photodynamic destruction limited to endometrial layers in a case submitted to hysterectomy. |

| [71] | Abnormal uterine bleeding | 4 | >30 years | PS: 5-ALA, 1.5–2 mL, 100–400 mg/mL solution, iu. DLI: 4–6 h Light: 635 nm, 160 J/cm2 | At least 152 days | Necrosis was found three days after PDT. Foci of preserved endometrium, no fibrosis or adhesions in all patients. Obs.: Hysterectomy performed 3, 35, 92 and 152 days after PDT. |

| [72] | Abnormal uterine bleeding | 11 | 42.3 years (median age) | PS: 5-ALA, iu. DLI: 3–6 h Light: 636 nm, 160 J/cm2 | Six months | There was a significant reduction in menstrual blood loss up to three months after treatment. Later on, the PDT effect was less obvious Obs.: PDT repetition in four cases |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Correia-Barros, G.; Serambeque, B.; Carvalho, M.J.; Marto, C.M.; Pineiro, M.; Pinho e Melo, T.M.V.D.; Botelho, M.F.; Laranjo, M. Applications of Photodynamic Therapy in Endometrial Diseases. Bioengineering 2022, 9, 226. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering9050226

Correia-Barros G, Serambeque B, Carvalho MJ, Marto CM, Pineiro M, Pinho e Melo TMVD, Botelho MF, Laranjo M. Applications of Photodynamic Therapy in Endometrial Diseases. Bioengineering. 2022; 9(5):226. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering9050226

Chicago/Turabian StyleCorreia-Barros, Gabriela, Beatriz Serambeque, Maria João Carvalho, Carlos Miguel Marto, Marta Pineiro, Teresa M. V. D. Pinho e Melo, Maria Filomena Botelho, and Mafalda Laranjo. 2022. "Applications of Photodynamic Therapy in Endometrial Diseases" Bioengineering 9, no. 5: 226. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering9050226

APA StyleCorreia-Barros, G., Serambeque, B., Carvalho, M. J., Marto, C. M., Pineiro, M., Pinho e Melo, T. M. V. D., Botelho, M. F., & Laranjo, M. (2022). Applications of Photodynamic Therapy in Endometrial Diseases. Bioengineering, 9(5), 226. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering9050226