Towards Wideband Characterization and Modeling of In-Body to On-Body Intrabody Communication Channels

Abstract

1. Introduction

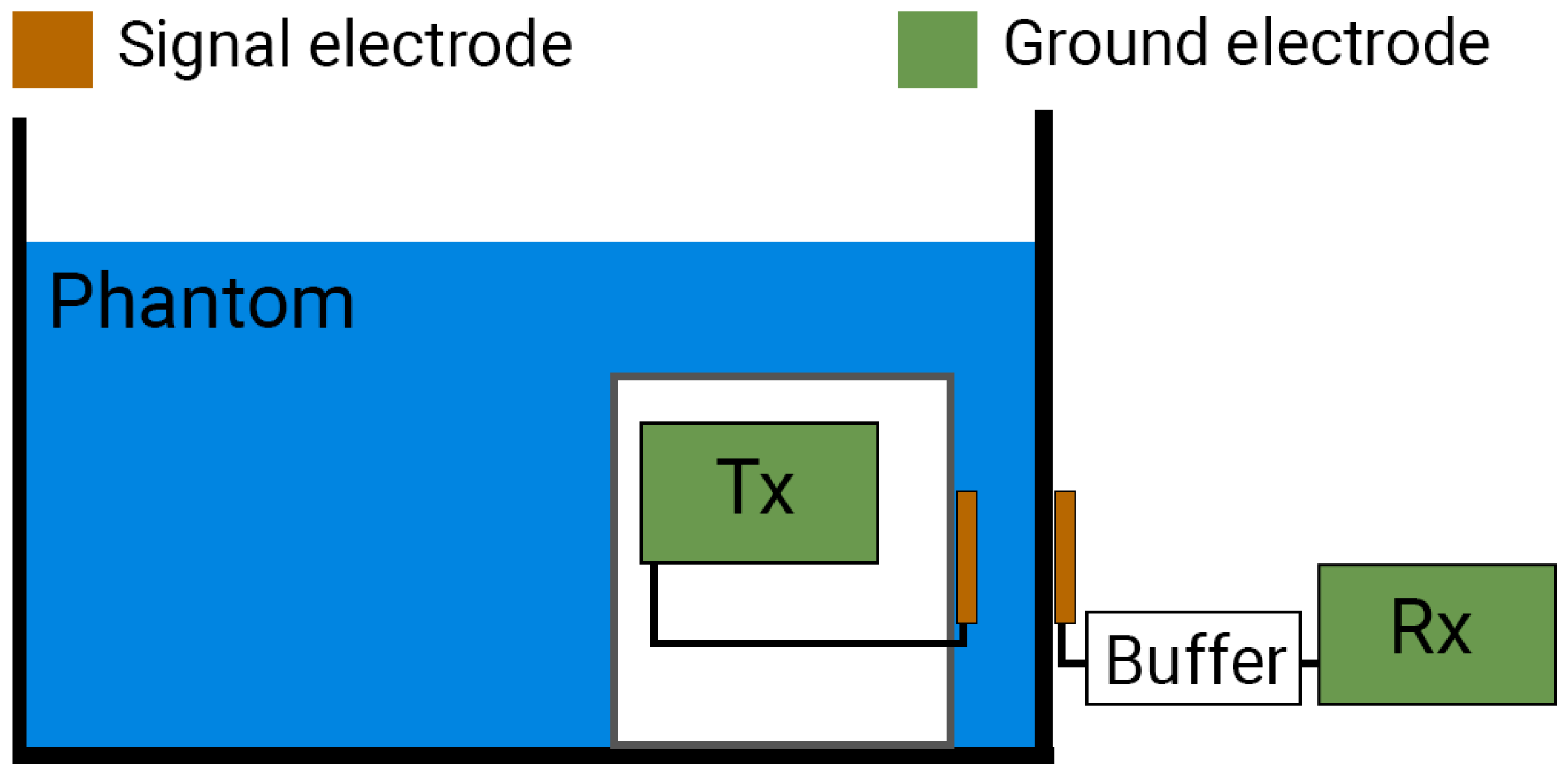

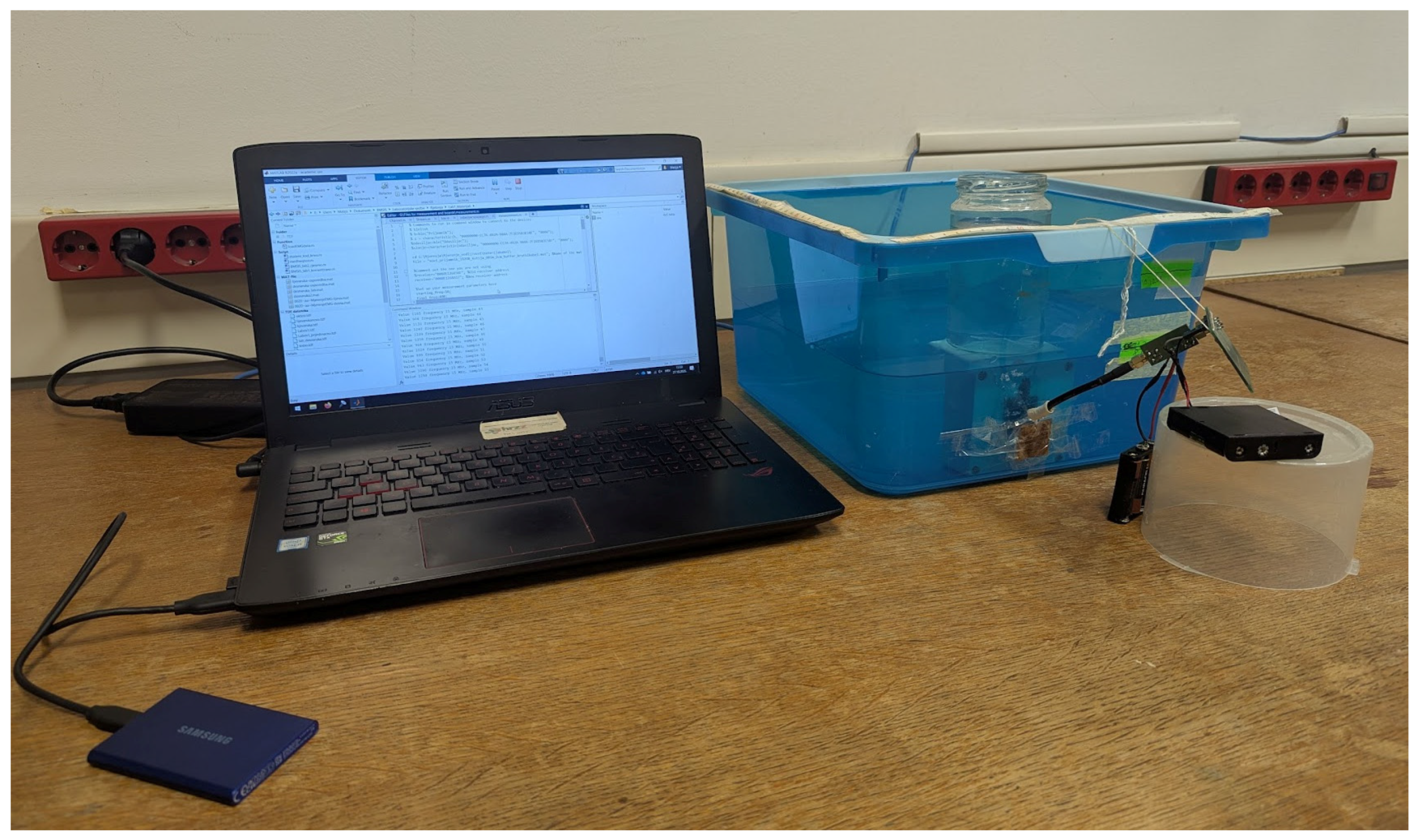

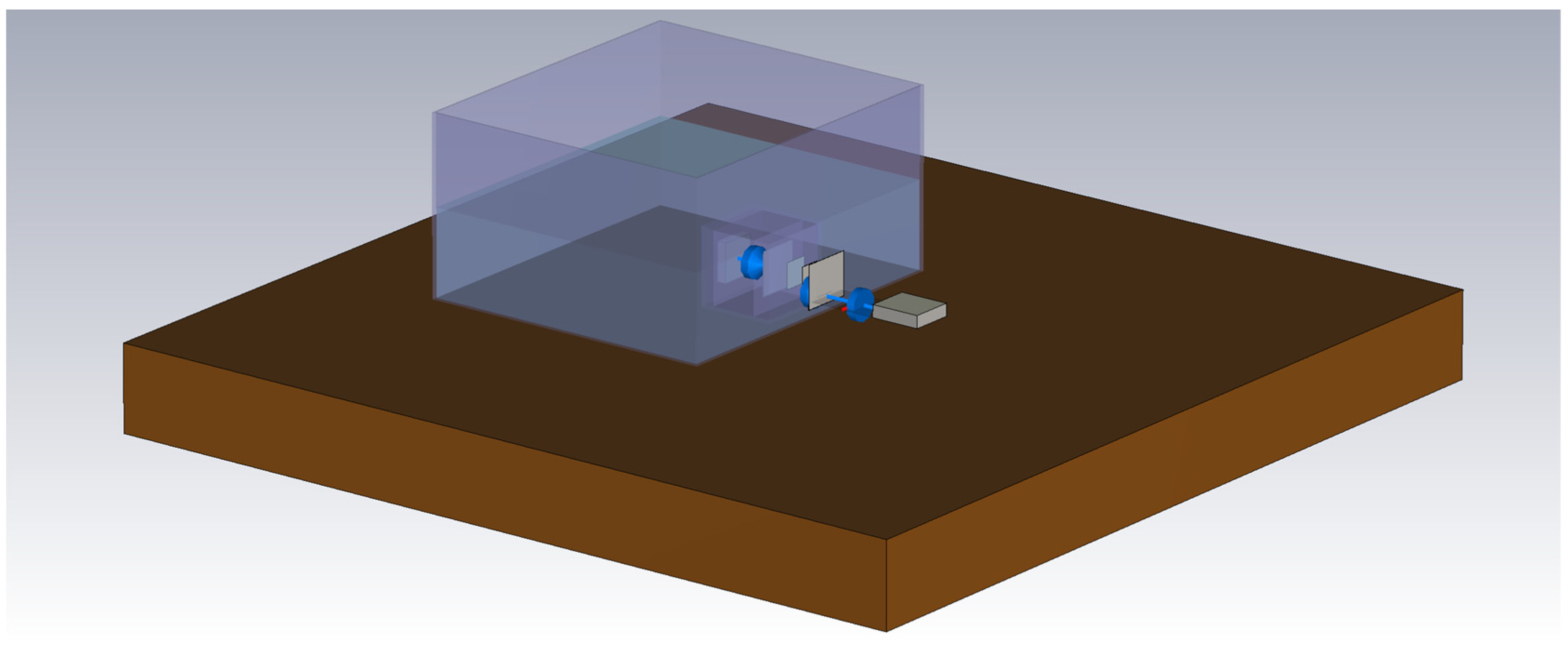

2. Measurement Setup

2.1. Components of the Measurement Setup

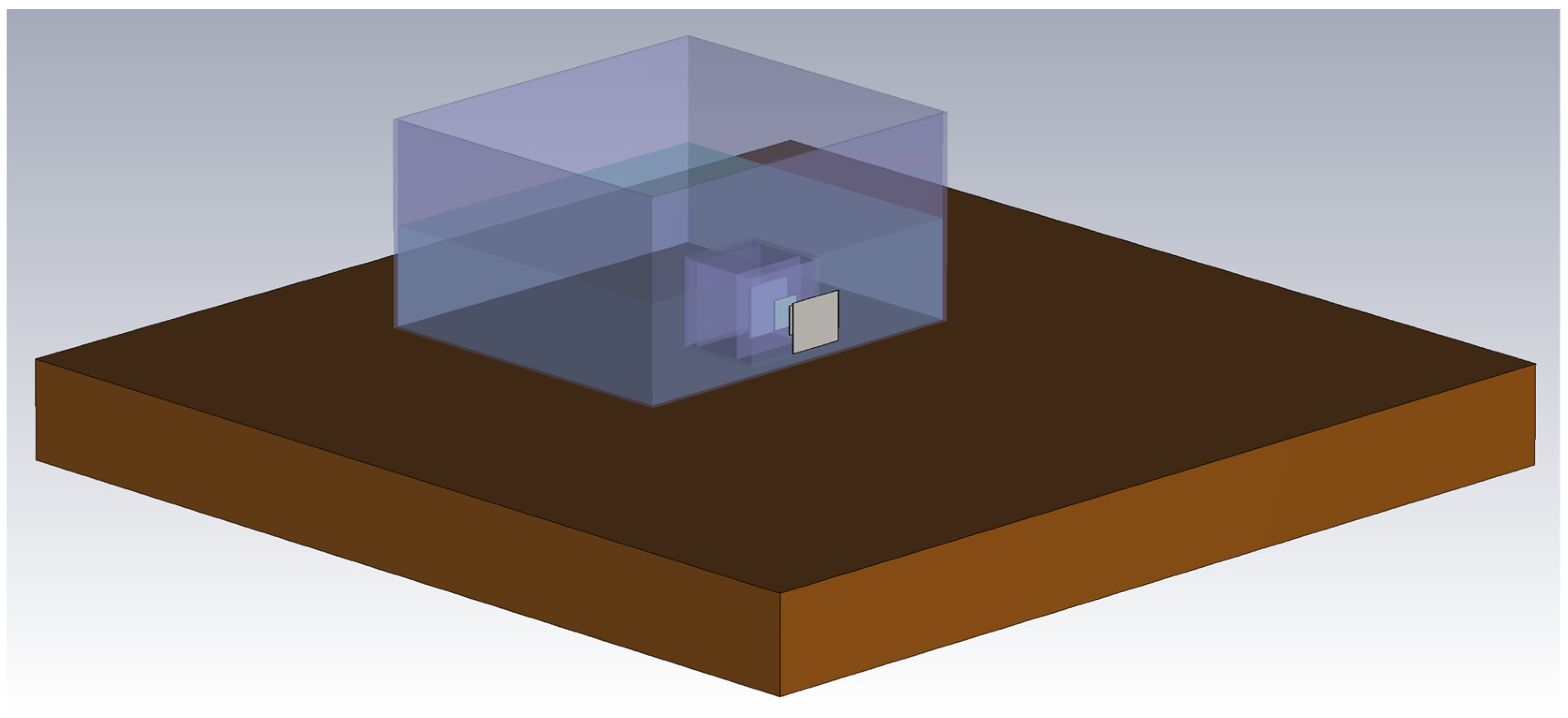

2.1.1. The Liquid Phantom

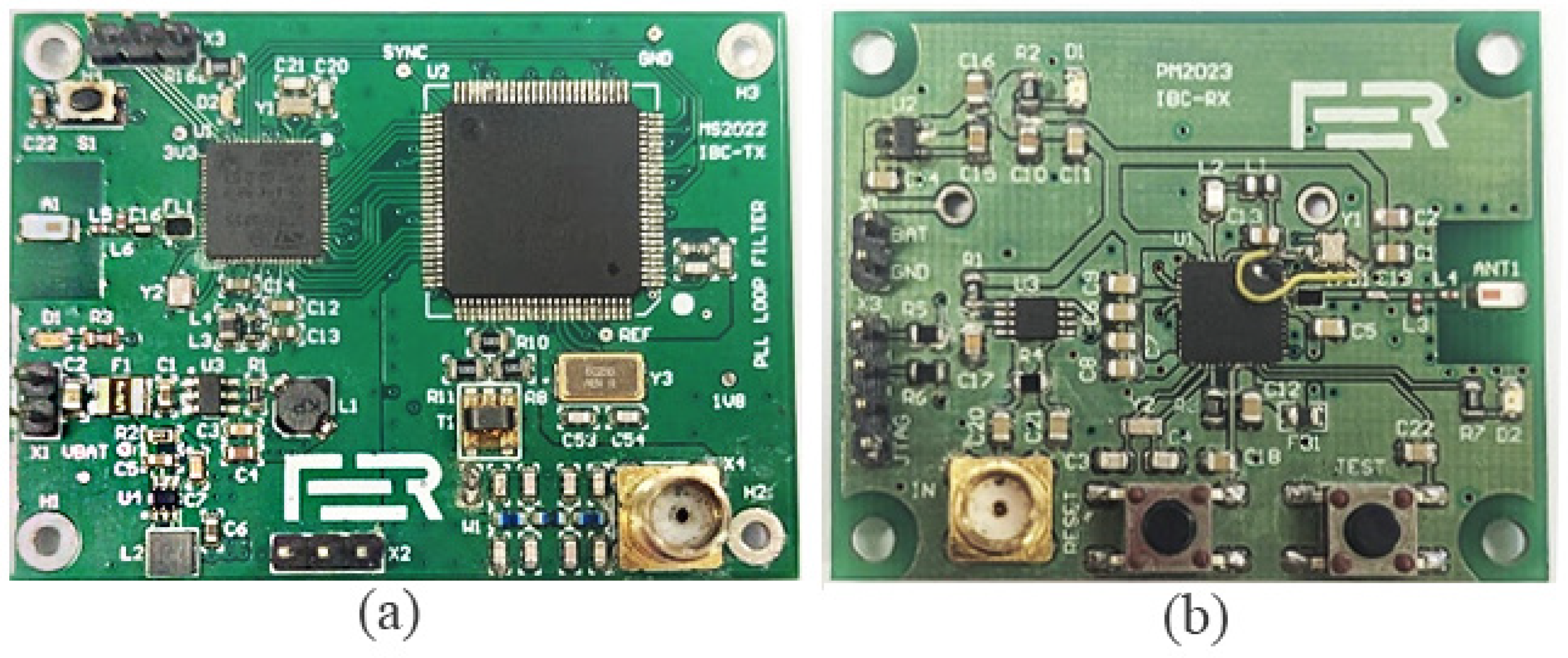

2.1.2. Battery-Powered Transmitter and Receiver

2.1.3. Buffer

2.2. Measurement Procedure

3. IB2OB CC IBC Models

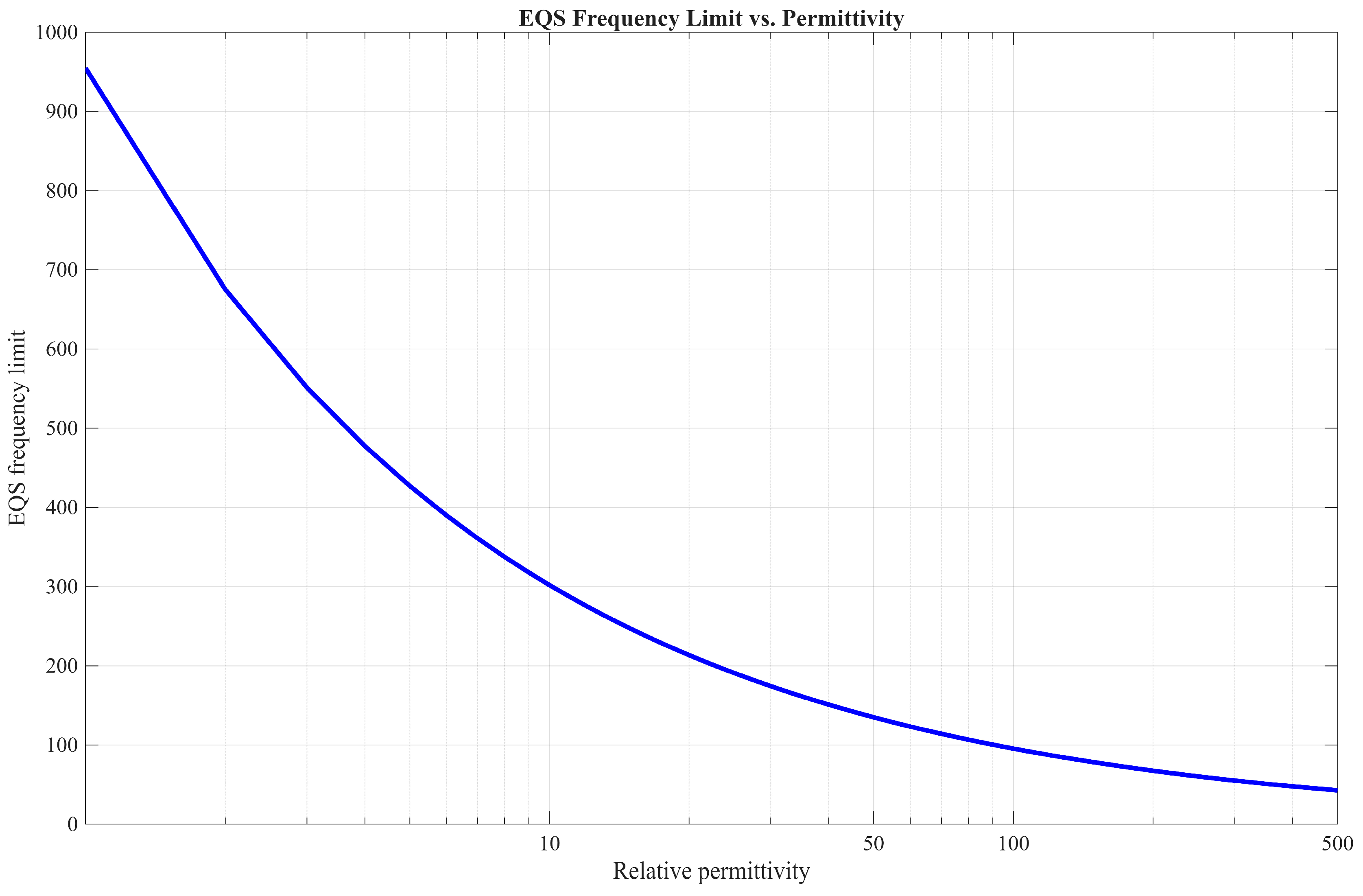

3.1. EQS Circuit Model

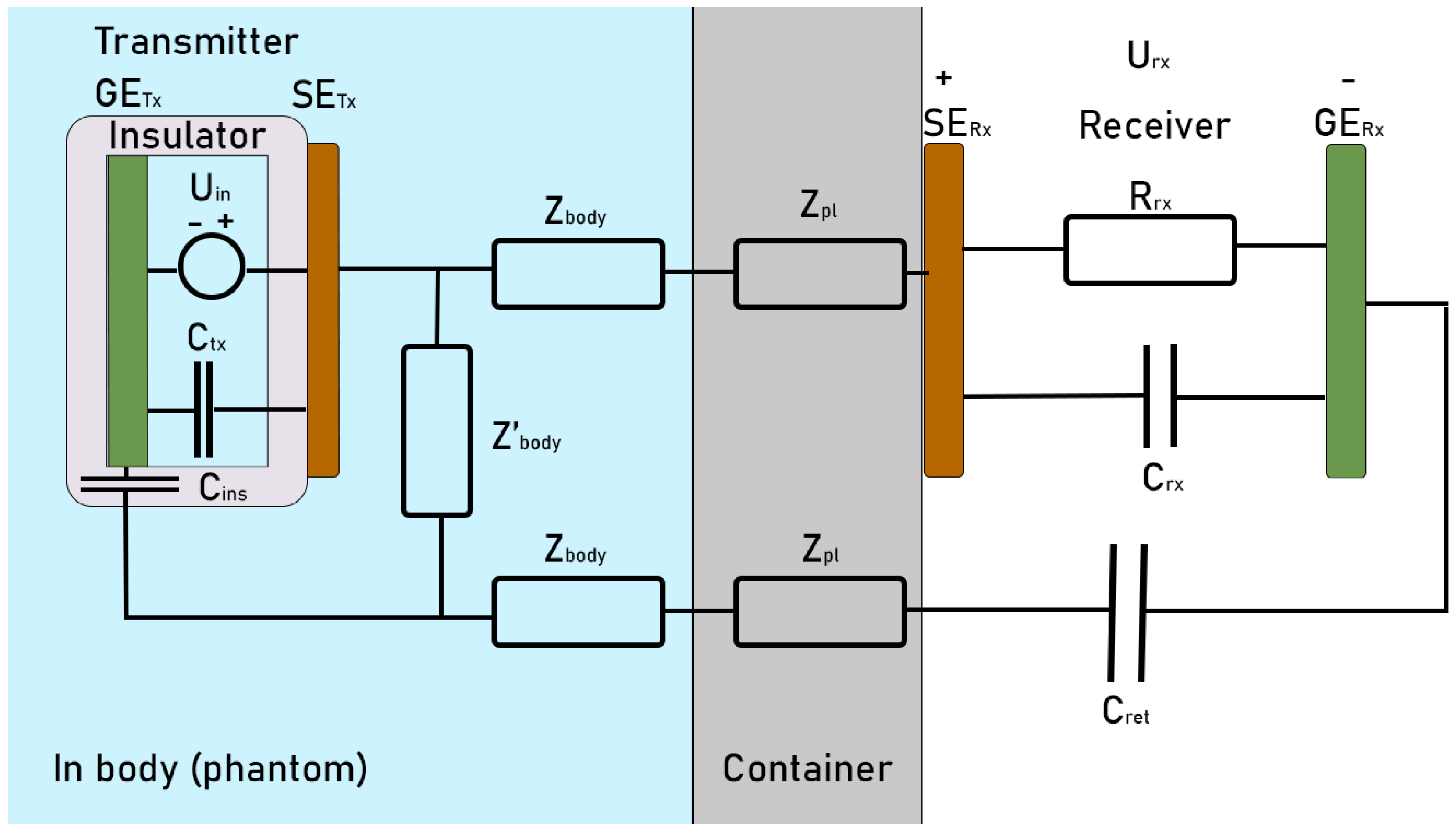

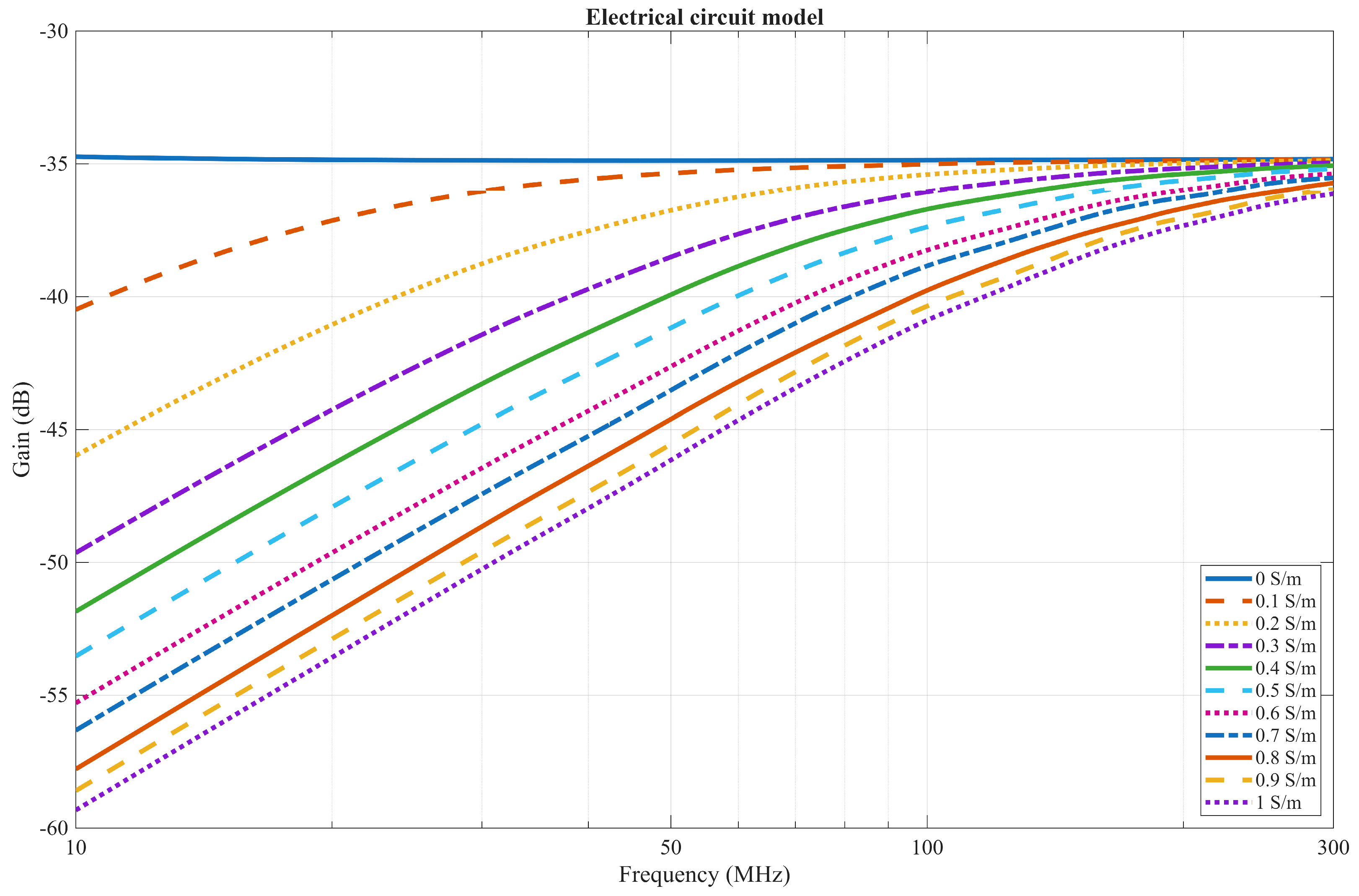

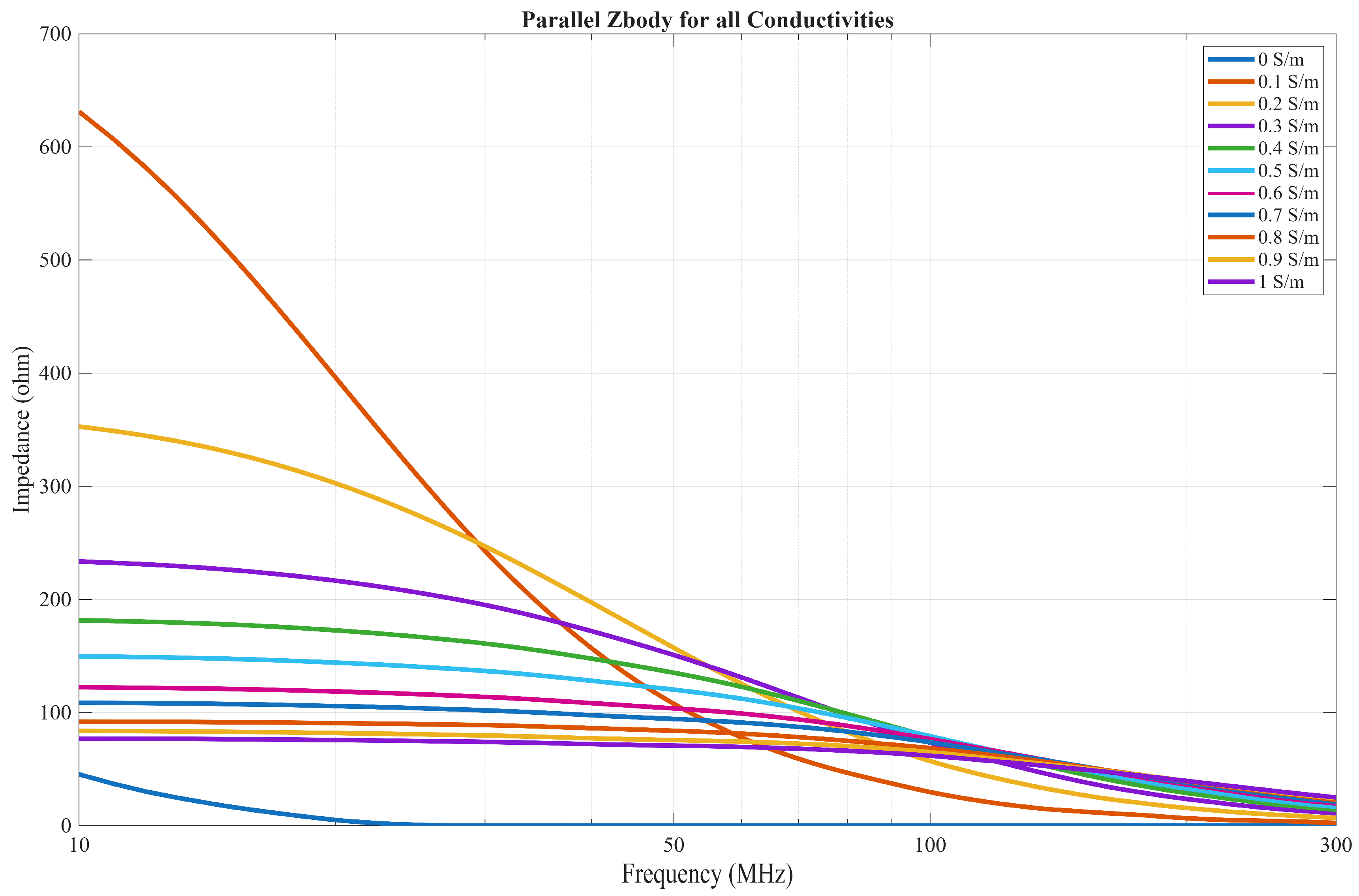

3.2. Electrical Circuit Model

3.3. Electromagnetic FEM Solver

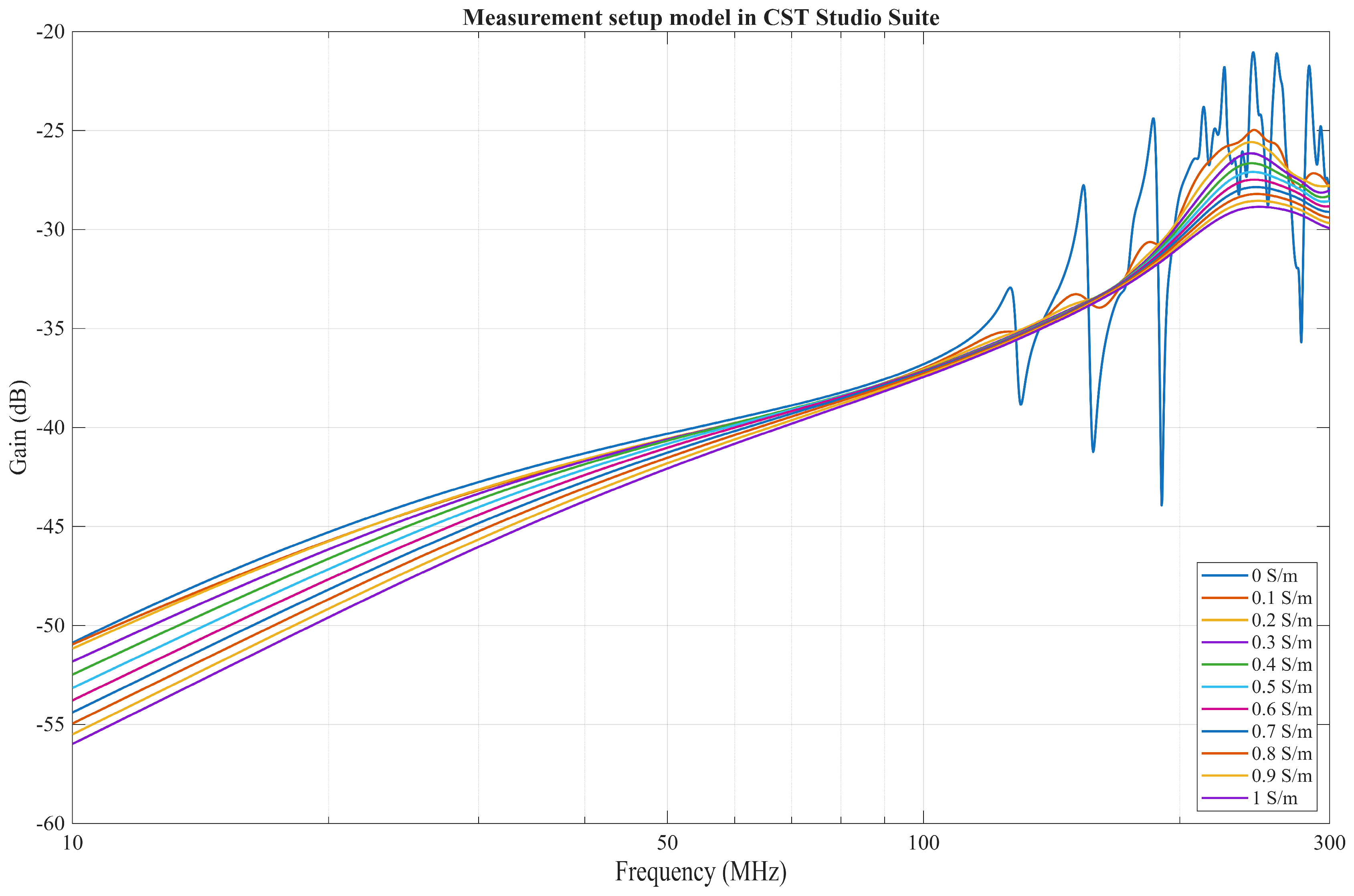

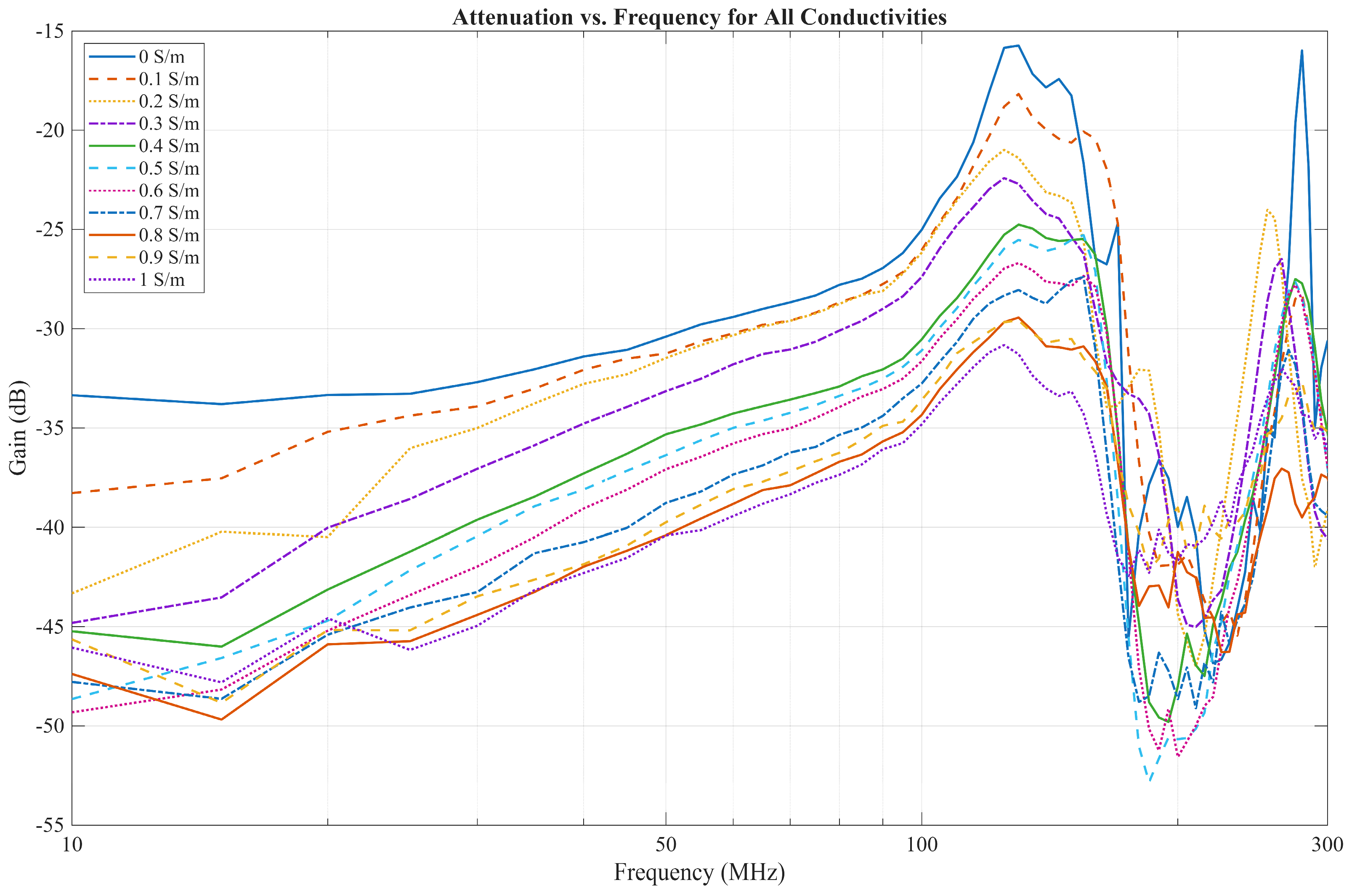

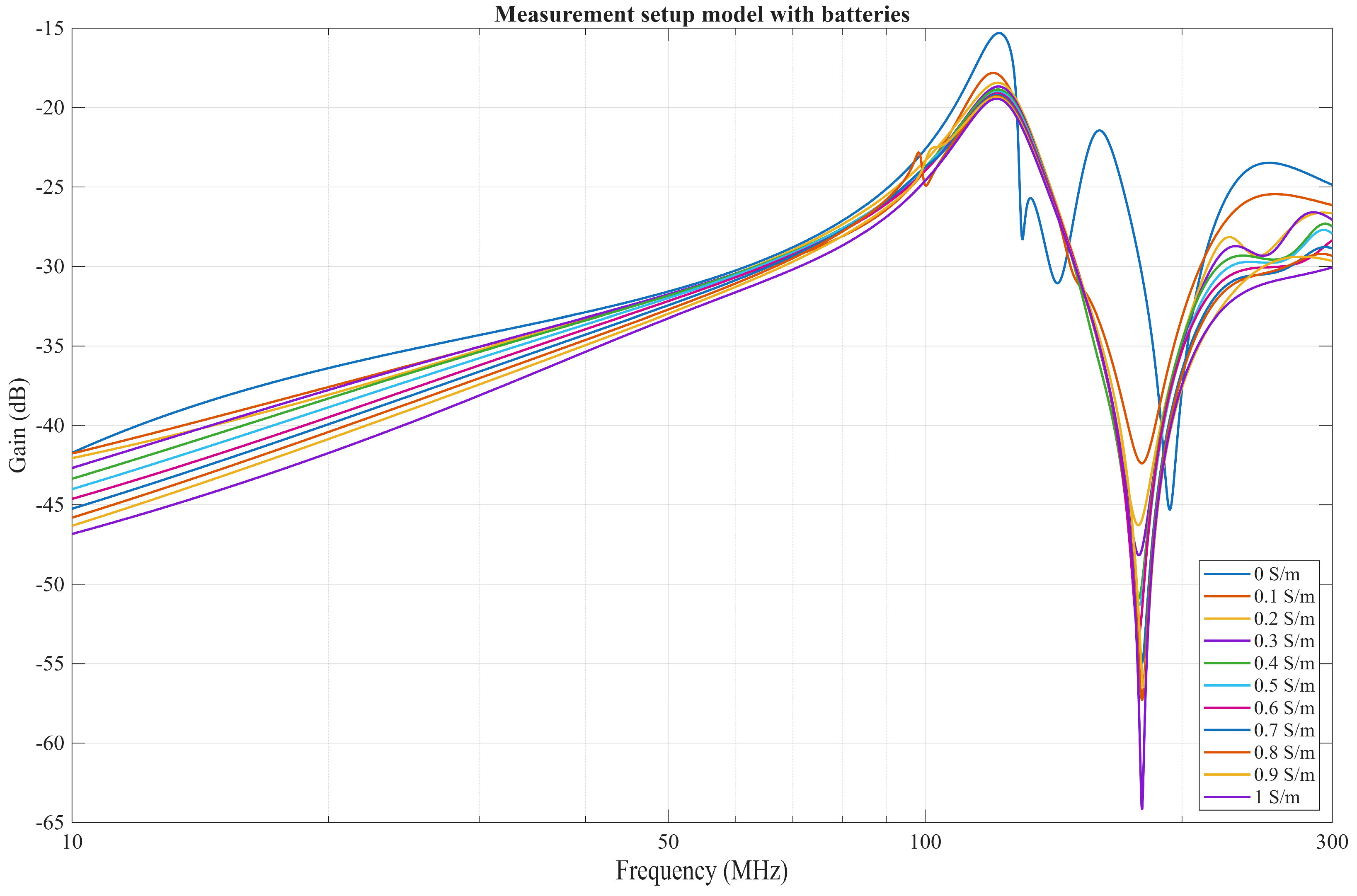

4. Results and Discussion

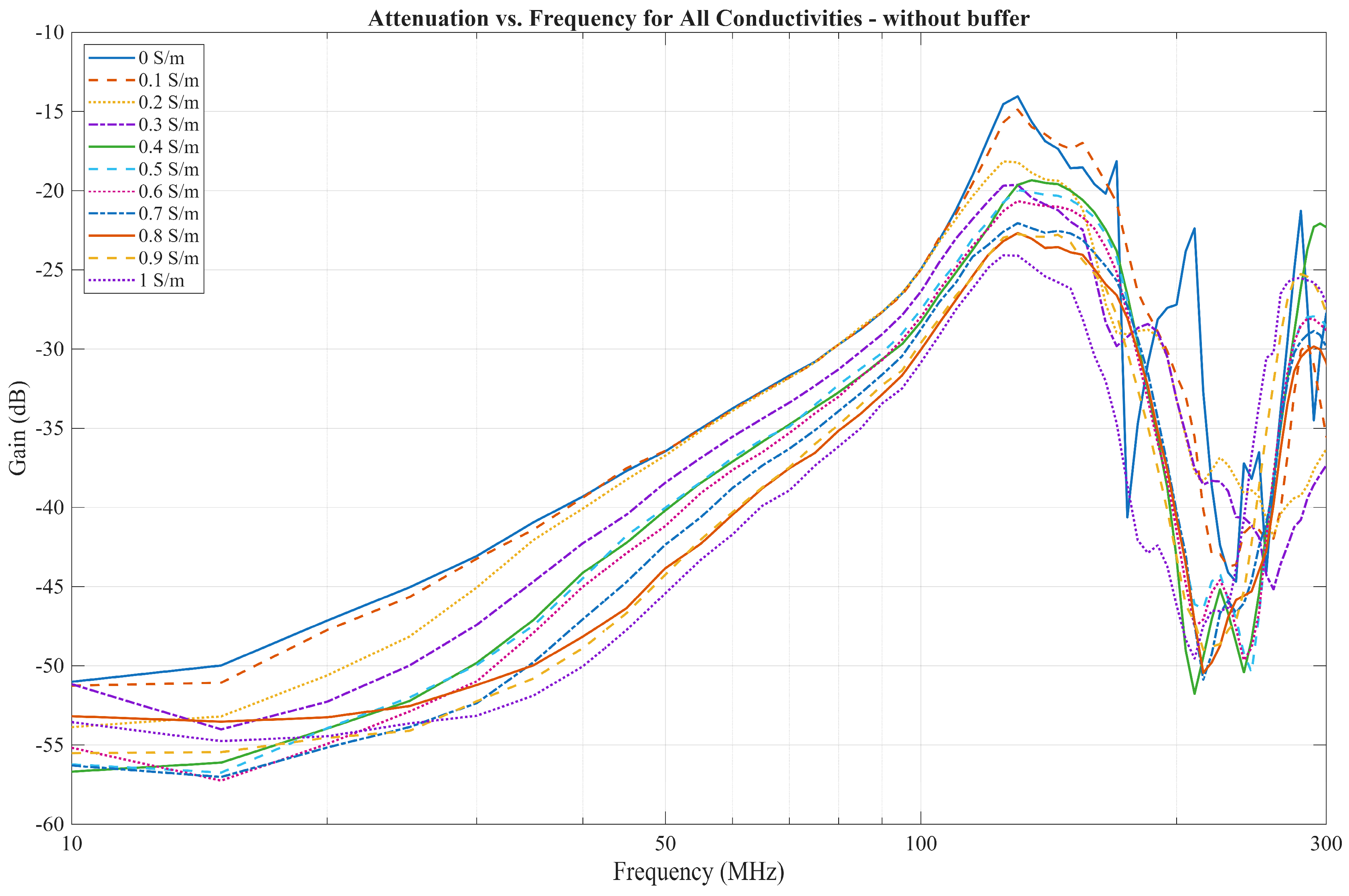

4.1. EQS Characterization of an IB2OB Communication Channel

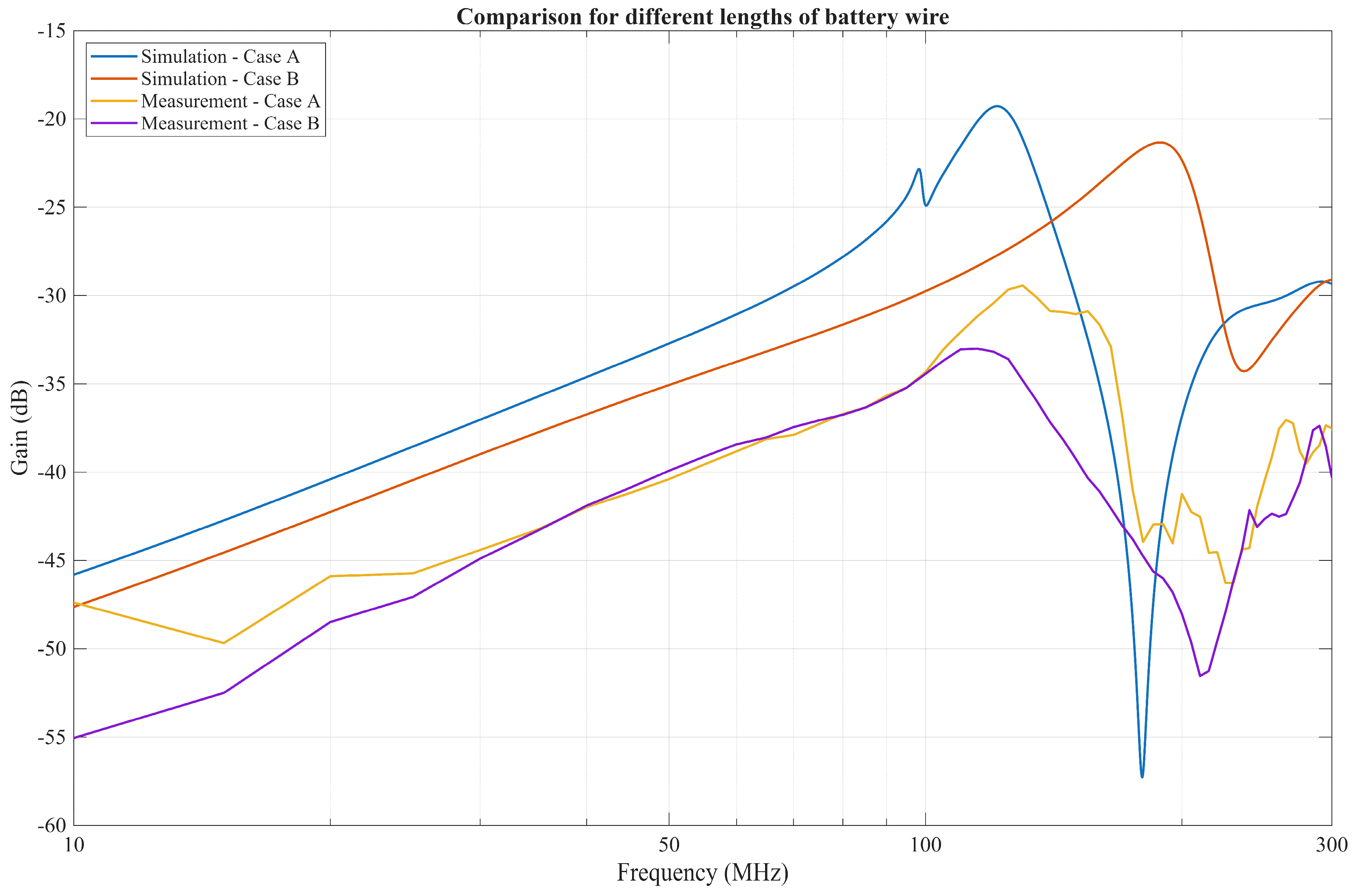

4.2. Comparison of a FEM Solver Model with Measurement Results

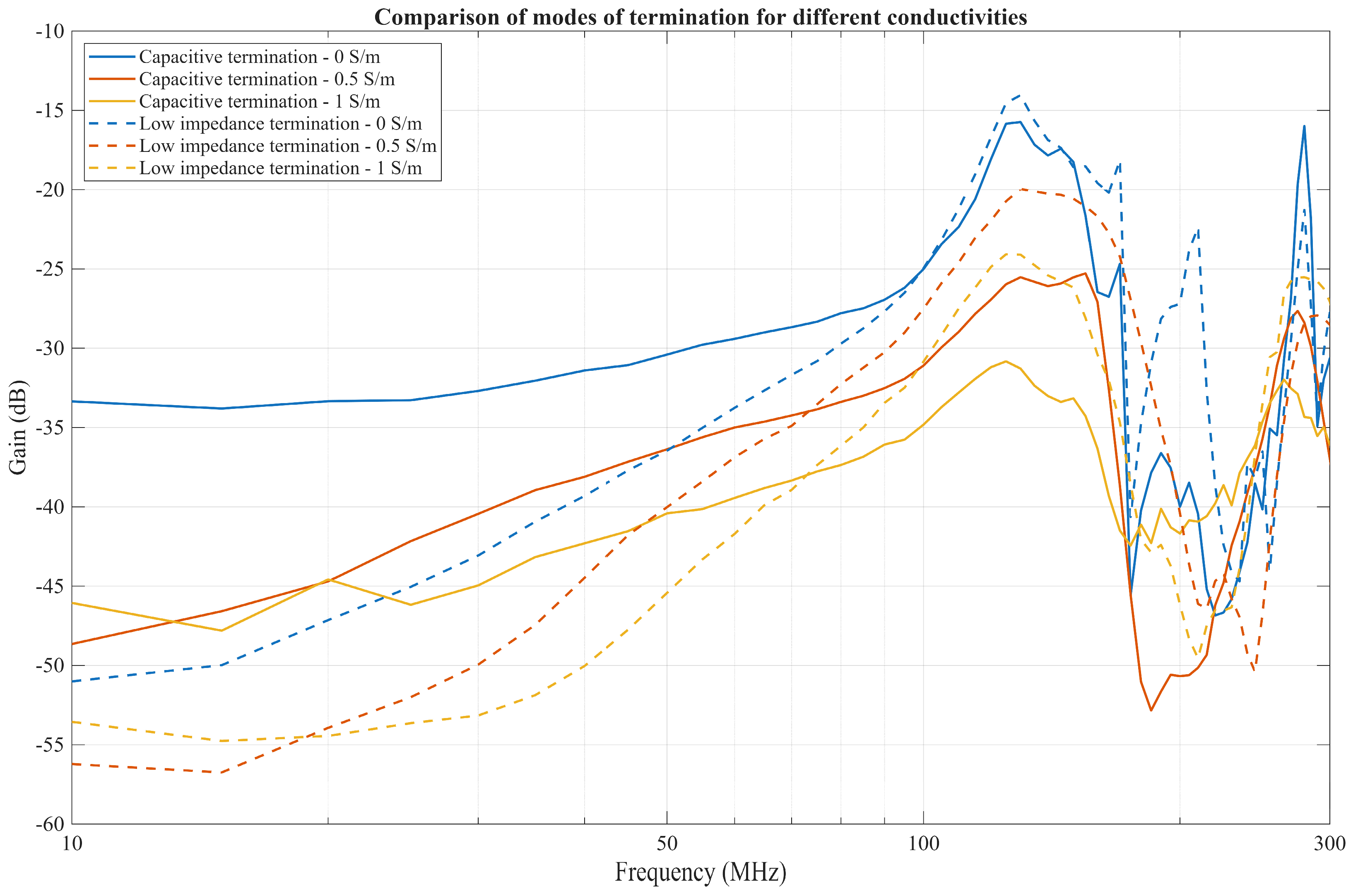

4.3. Comparison of Low Resistance Termination and Capacitive Termination

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IBC | Intrabody communication |

| WBAN | Wireless body area network |

| CC | Capacitive coupling |

| GC | Galvanic coupling |

| SE | Signal electrode |

| GE | Ground electrode |

| Tx | Transmitter |

| Rx | Receiver |

| IB2IB | In-body to in-body |

| IB2OB | In-body to on-body |

| EQS | Electro-quasistatic |

| FEM | Finite element method |

| PCB | Printed circuit board |

References

- Celik, A.; Salama, K.N.; Eltawil, A.M. The Internet of Bodies: A Systematic Survey on Propagation Characterization and Channel Modeling. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 321–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čuljak, I.; Lučev Vasić, Ž.; Mihaldinec, H.; Džapo, H. Wireless Body Sensor Communication Systems Based on UWB and IBC Technologies: State-of-the-Art and Open Challenges. Sensors 2020, 20, 3587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fares, N.; Sherratt, R.S.; Elhajj, I.H. Directing and Orienting ICT Healthcare Solutions to Address the Needs of the Aging Population. Healthcare 2021, 9, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanzo, I.; Sen, D.; Rhein, L.; Guler, U. Respiratory Monitoring: Current State of the Art and Future Roads. IEEE Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2022, 15, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.J.; Yang, W.; Dermody, G.; Ghasemian, M.; Adibi, S.; Haskell-Dowland, P. No Soldiers Left Behind: An IoT-Based Low-Power Military Mobile Health System Design. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 201498–201515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aledhari, M.; Razzak, R.; Qolomany, B.; Al-Fuqaha, A.; Saeed, F. Biomedical IoT: Enabling Technologies, Architectural Elements, Challenges, and Future Directions. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 31306–31339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D.; Maity, S.; Chatterjee, B.; Sen, S. Enabling Covert Body Area Network using Electro-Quasistatic Human Body Communication. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 4160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roglić, M.; Klaić, L.; Wei, Z.; Gao, Y.; Lučev Vasić, Ž. Comparison of Different Configurations for the Implantable Capacitive Intrabody Communication on a Two-Layer Phantom. In IFMBE Proceedings, Proceedings of the 9th European Medical and Biological Engineering Conference, Portoroz, Slovenia, 9–13 June 2024; Jarm, T., Šmerc, R., Mahnič-Kalamiza, S., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 112, pp. 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office of the Commissioner, FDA. Informs Patients, Providers and Manufacturers About Potential Cybersecurity Vulnerabilities in Certain Medical Devices with Bluetooth Low Energy; FDA: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2020. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-informs-patients-providers-and-manufacturers-about-potential-cybersecurity-vulnerabilities-0 (accessed on 2 January 2024).

- Zimmerman, T.G. Personal Area Networks: Near-field intrabody communication. IBM Syst. J. 1996, 35, 609–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegmüller, M.S. Intra-Body Communication for Biomedical Sensor Networks. Ph.D. Thesis, ETH Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.D.; Alvarez-Botero, G.A.; De Sousa, F.R. Characterization and Modeling of the Capacitive HBC Channel. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2015, 64, 2626–2635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltsavias, S.; Van Treuren, W.; Sawaby, A.; Baker, S.W.; Sonnenburg, J.L.; Arbabian, A. Gut Microbiome Redox Sensors with Ultrasonic Wake-Up and Galvanic Coupling Wireless Links. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2023, 70, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alquaydheb, I.N.; Khorshid, A.E.; Eltawil, A.M. Analysis and estimation of intra-body communications path loss for galvanic coupling. In Advances in Body Area Networks I; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcala-Medel, J.; Lim, J.; Li, Y. Investigation of Galvanic and Capacitively Coupled Intrabody Transmission Around the Human Head. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Texas Symposium on Wireless and Microwave Circuits and Systems (WMCS), Waco, TX, USA, 26–28 May 2020; IEEE: Solaris, Singapore, 2020; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Hao, Q.; Song, Y.; Wang, J.; Huang, R.; Liu, Y. Modeling and Characterization of the Implant Intra-Body Communication Based on Capacitive Coupling Using a Transfer Function Method. Sensors 2014, 14, 1740–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Nie, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wang, L.; Hao, Y. Characterization of In-Body Radio Channels for Wireless Implants. IEEE Sens. J. 2017, 17, 1528–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Song, Y.; Hou, Y.; Li, N.; Jiang, Y.; Sulaman, M.; Hao, Q. Comparable Investigation of Characteristics for Implant Intra-Body Communication Based on Galvanic and Capacitive Coupling. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuits Syst. 2019, 13, 1747–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roglić, M.; Gao, Y.; Artić, I.; Lučev Vasić, Ž. Characterization of Implantable Capacitive Intrabody Communication Channel between In-body and On-body Devices on a Liquid Phantom. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Symposium on Medical Measurements and Applications (MeMeA), Jeju, Republic of Korea, 14–16 June 2023; IEEE: Solaris, Singapore, 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuk, B.; Kim, B.; Park, S.; Huh, Y.; Bae, J. An Implantable Body Channel Communication System with 3.7-pJ/b Reception and 34-pJ/b Transmission Efficiencies. IEEE Solid-State Circuits Lett. 2020, 3, 50–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maity, S.; He, M.; Nath, M.; Das, D.; Chatterjee, B.; Sen, S. Bio-Physical Modeling, Characterization, and Optimization of Electro-Quasistatic Human Body Communication. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2019, 66, 1761–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, A.; Acebal, C.; Heyd, B.; White, T.; Kainth, G.; Datta, A.; Sen, S.; Khalifa, A.; Chatterjee, B. Exploring the Effects of Encapsulated Capacitive and Galvanic Transmitters for Implant-to-Wearable Scenarios in Human Body Communication. In Proceedings of the 2024 46th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), Orlando, FL, USA, 15–19 July 2024; IEEE: Solaris, Singapore, 2024; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.; Lee, J.; Lee, K.-R.; Lee, J.; Kim, M.; Lee, Y.; Bae, J.; Yoo, H.-J. A Four-Camera VGA-Resolution Capsule Endoscope System with 80-Mb/s Body Channel Communication Transceiver and Sub-Centimeter Range Capsule Localization. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 2019, 54, 538–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vizziello, A.; Galluccio, L.; Magarini, M.; Savazzi, P.; Biglioli, F.; Bolognesi, F.; Talpo, F.; Biella, G.; Magenes, G. An Implantable System for Neural Communication and Stimulation: Design and Implementation. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2022, 60, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryser, A.; Schmid, T.; Bereuter, L.; Burger, J.; Reichlin, T.; Niederhauser, T.; Haeberlin, A. Modulation Scheme Analysis for Low-Power Leadless Pacemaker Synchronization Based on Conductive Intracardiac Communication. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuits Syst. 2022, 16, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ashmouny, K.M.; Boldt, C.; Ferguson, J.E.; Erdman, A.G.; Redish, A.D.; Yoon, E. IBCOM (intra-brain communication) microsystem: Wireless transmission of neural signals within the brain. In Proceedings of the 2009 Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 3–6 September 2009; IEEE: Solaris, Singapore, 2009; pp. 2054–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadleir, R.; Minhas, A.S. (Eds.) Electrical Properties of Tissues: Quantitative Magnetic Resonance Mapping. In Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennati, F.; Angelucci, A.; Morelli, L.; Bardini, S.; Barzanti, E.; Cavallini, F.; Conelli, A.; Di Federico, G.; Paganelli, C.; Aliverti, A. Electrical Impedance Tomography: From the Traditional Design to the Novel Frontier of Wearables. Sensors 2023, 23, 1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baby, L.Y.; Bedran, R.S.; Doumit, A.; El Hassan, R.H.; Maalouf, N. Past, present, and future of electrical impedance tomography and myography for medical applications: A scoping review. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 1486789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Garudadri, H.; Mercier, P.P. Channel Modeling of Miniaturized Battery-Powered Capacitive Human Body Communication Systems. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2017, 64, 452–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Analog Devices Inc. Fast, Voltage-Out, DC to 440 MHz, 95 dB Logarithmic Amplifier AD8310; Analog Devices Inc.: Boston, MA, USA, 2010; Available online: https://www.analog.com/media/en/technical-documentation/data-sheets/ad8310.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2022).

- Callejon, M.A.; Reina-Tosina, J.; Naranjo-Hernandez, D.; Roa, L.M. Measurement Issues in Galvanic Intrabody Communication: Influence of Experimental Setup. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2015, 62, 2724–2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avlani, S.; Nath, M.; Maity, S.; Sen, S. A 100 KHz–1 GHz Termination-dependent Human Body Communication Channel Measurement using Miniaturized Wearable Devices. In Proceedings of the 2020 Design, Automation & Test in Europe Conference & Exhibition (DATE), Grenoble, France, 9–13 March 2020; IEEE: Solaris, Singapore, 2020; pp. 650–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, C. Compilation of the Dielectric Properties of Body Tissues at RF and Microwave Frequencies; Defense Technical Information Center: Fort Belvoir, VA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, B.; Nath, M.; Kumar, G.; Xiao, S.; Jayant, K.; Sen, S. Biphasic quasistatic brain communication for energy-efficient wireless neural implants. Nat. Electron. 2023, 6, 703–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lučev Vasić, Ž. Intrabody Communication Based on Capacitive Method. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Zagreb, Zagreb, Croatia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Nath, M.; Maity, S.; Sen, S. Toward Understanding the Return Path Capacitance in Capacitive Human Body Communication. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2020, 67, 1879–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lučev, Ž.; Krois, I.; Cifrek, M. Intrabody Communication in Biotelemetry; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 351–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Roglić, M.; Gao, Y.; Lučev Vasić, Ž. Towards Wideband Characterization and Modeling of In-Body to On-Body Intrabody Communication Channels. Bioengineering 2026, 13, 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering13010042

Roglić M, Gao Y, Lučev Vasić Ž. Towards Wideband Characterization and Modeling of In-Body to On-Body Intrabody Communication Channels. Bioengineering. 2026; 13(1):42. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering13010042

Chicago/Turabian StyleRoglić, Matija, Yueming Gao, and Željka Lučev Vasić. 2026. "Towards Wideband Characterization and Modeling of In-Body to On-Body Intrabody Communication Channels" Bioengineering 13, no. 1: 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering13010042

APA StyleRoglić, M., Gao, Y., & Lučev Vasić, Ž. (2026). Towards Wideband Characterization and Modeling of In-Body to On-Body Intrabody Communication Channels. Bioengineering, 13(1), 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering13010042