Three-Dimensional Visualization and Detection of the Pulmonary Venous–Left Atrium Connection Using Artificial Intelligence in Fetal Cardiac Ultrasound Screening

Abstract

1. Introduction

- RQ1: Can PV-LA connections be better visualized using conventional 2D ultrasound videos?

- RQ2: How can PV-LA connections be quantitatively evaluated?

- RQ3: Does our method contribute to improving TAPVC screening performance?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Preparation

2.2. Data Preprocessing and Augmentation

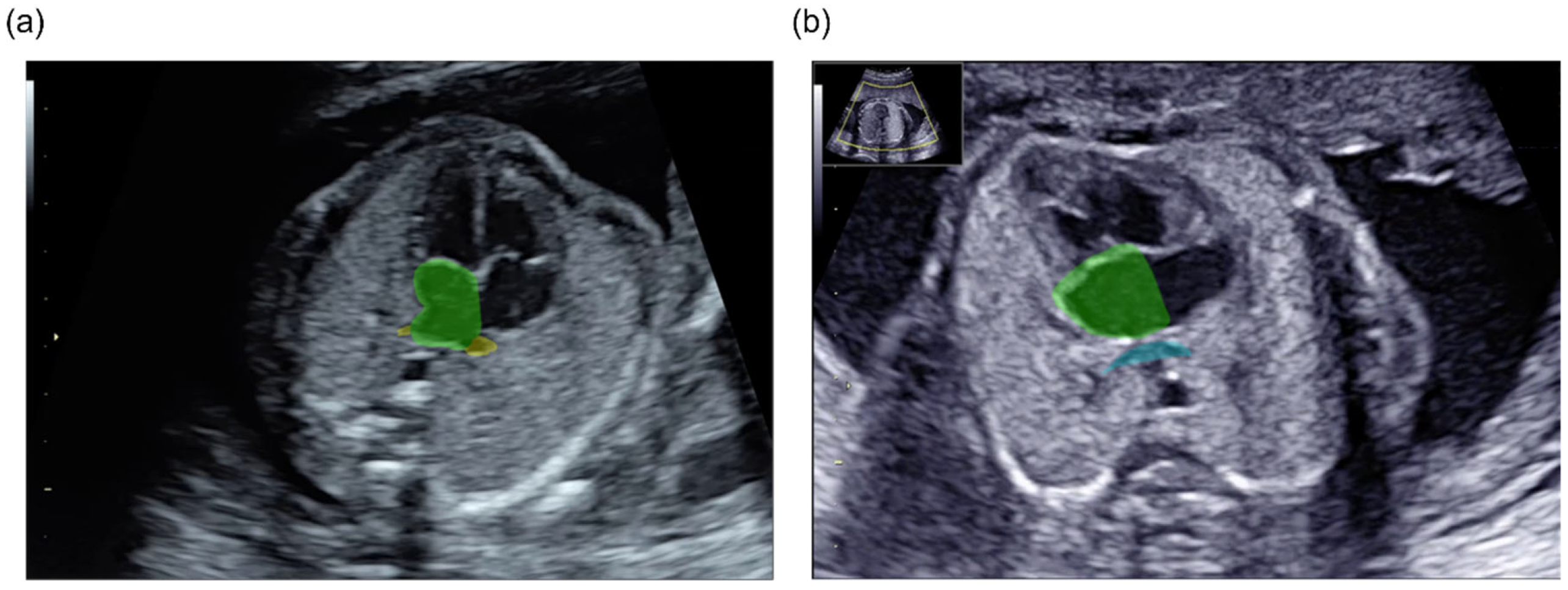

2.3. Three-Dimensional Segmentation

2.3.1. Three-Dimensional Segmentation Models

2.3.2. Training Environment and Implementation Details

2.3.3. Segmentation Performance Evaluation

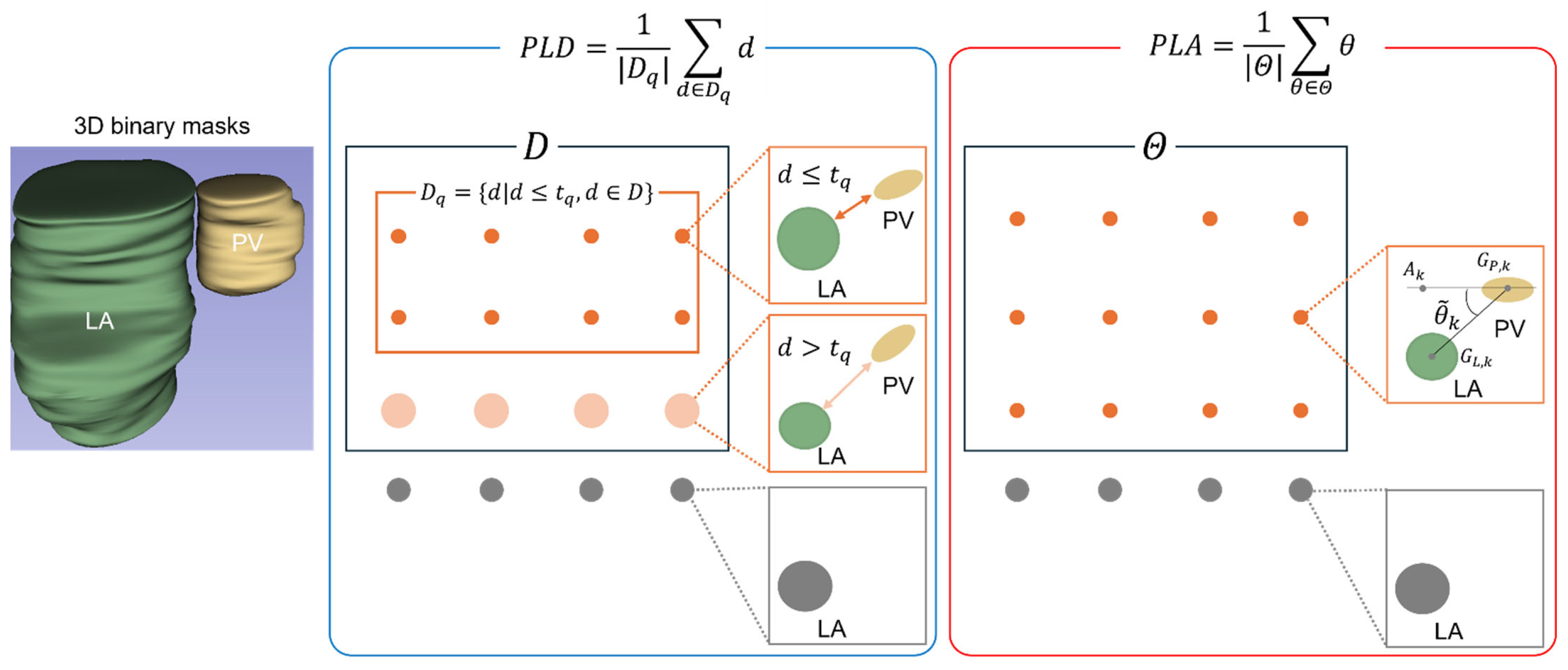

2.4. Quantitative Evaluation of the PV-LA Connection

2.4.1. PV-LA Distance (PLD)

2.4.2. PV-LA Angle (PLA)

2.5. Screening Performance Comparison

3. Results

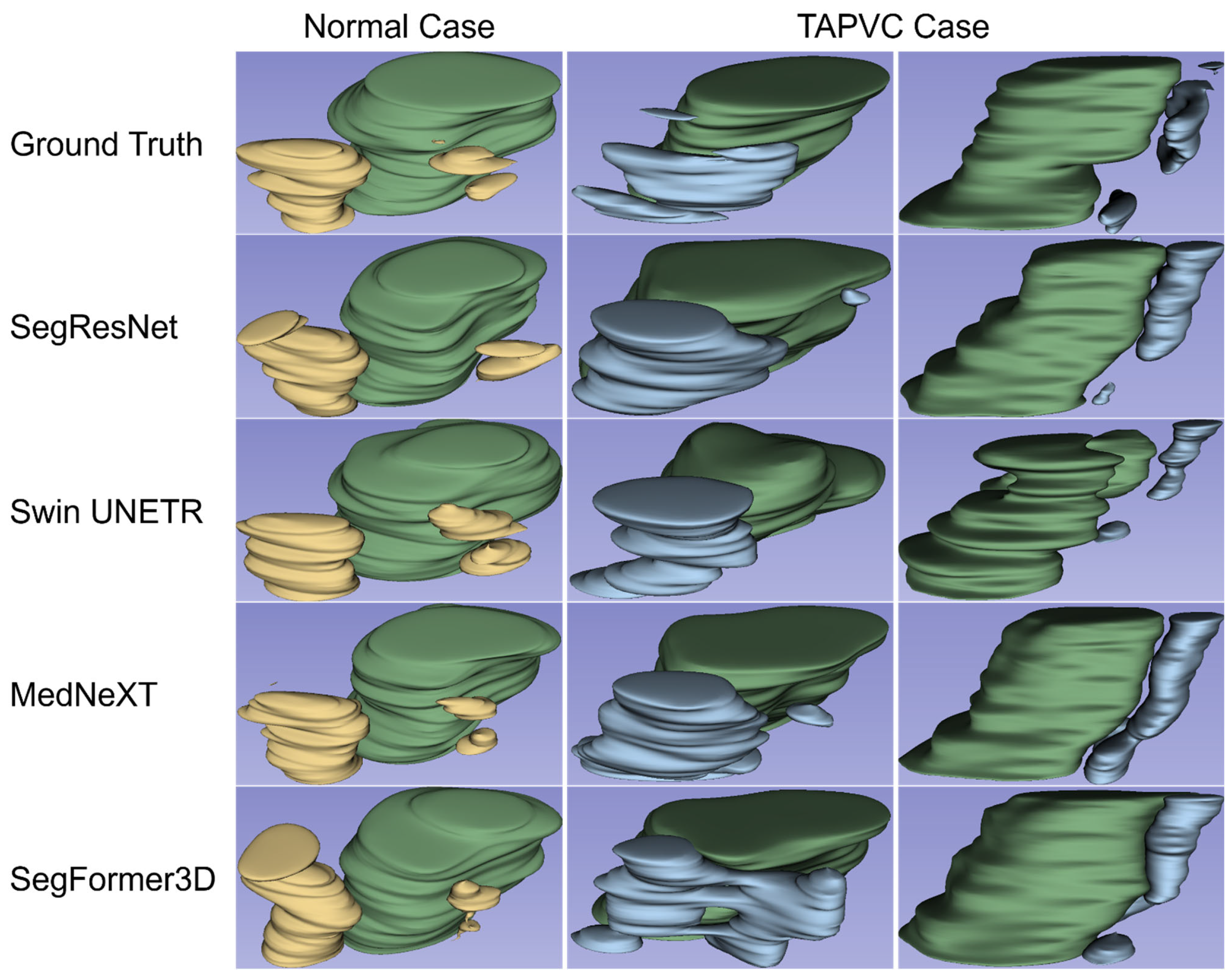

3.1. Three-Dimensional Visualization and Detection of the PV-LA Connection

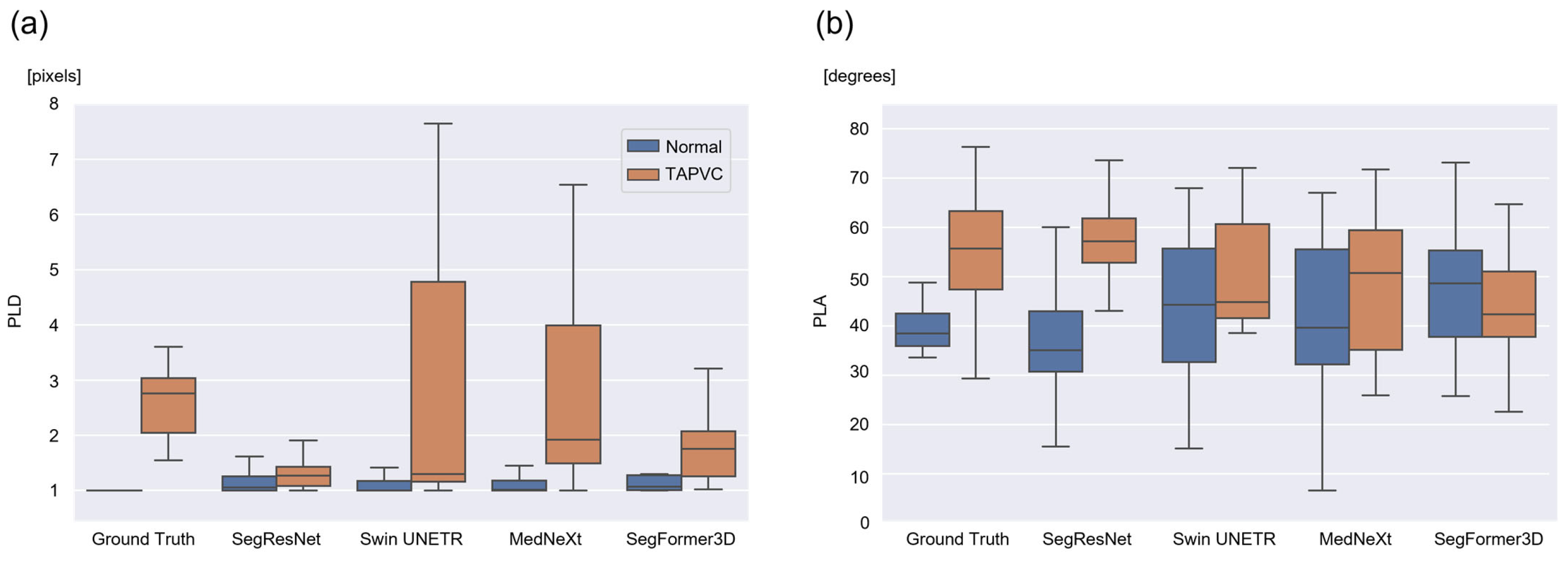

3.2. Calculation and Evaluation of the PLD and PLA

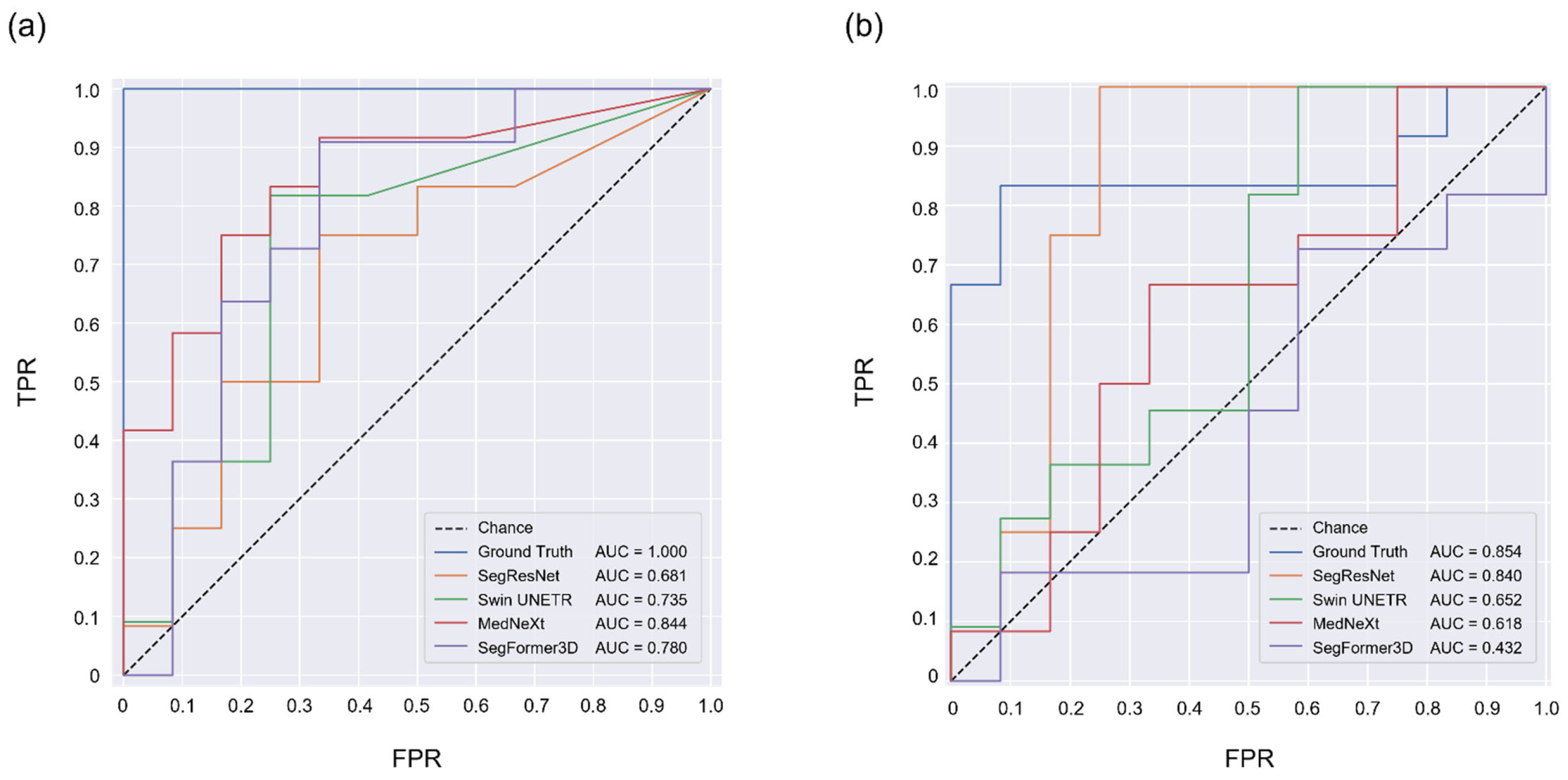

3.3. TAPVC Screening Performance Using the PLD and PLA

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Qiu, X.; Weng, Z.; Liu, M.; Chen, X.; Wu, Q.; Ling, W.; Ma, H.; Huang, H.; Lin, Y. Prenatal diagnosis and pregnancy outcomes of 1492 fetuses with congenital heart disease: Role of multidisciplinary-joint consultation in prenatal diagnosis. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 7564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donofrio, M.T.; Moon-Grady, A.J.; Hornberger, L.K.; Copel, J.A.; Sklansky, M.S.; Abuhamad, A.; Cuneo, B.F.; Huhta, J.C.; Jonas, R.A.; Krishnan, A.; et al. Diagnosis and treatment of fetal cardiac disease: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2014, 129, 2183–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, H.; Hirata, Y.; Inuzuka, R.; Hayashi, T.; Nagamine, H.; Ueda, T.; Nakayama, T. Initial national investigation of the prenatal diagnosis of congenital heart malformations in Japan-Regional Detection Rate and Emergency Transfer from 2013 to 2017. J Cardiol 2021, 78, 480–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Nisselrooij, A.E.L.; Teunissen, A.K.K.; Clur, S.A.; Rozendaal, L.; Pajkrt, E.; Linskens, I.H.; Rammeloo, L.; van Lith, J.M.M.; Blom, N.A.; Haak, M.C. Why are congenital heart defects being missed? Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 55, 747–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, Y.; Kobayashi, M.; Shinkawa, K.; Bilal, E.; Liao, J.; Nemoto, M.; Ota, M.; Nemoto, K.; Arai, T. Utility of synthetic musculoskeletal gaits for generalizable healthcare applications. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 6188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campanella, G.; Hanna, M.G.; Geneslaw, L.; Miraflor, A.; Werneck Krauss Silva, V.; Busam, K.J.; Brogi, E.; Reuter, V.E.; Klimstra, D.S.; Fuchs, T.J. Clinical-grade computational pathology using weakly supervised deep learning on whole slide images. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 1301–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, M.; Saito, Y.; Imaoka, H.; Saiko, M.; Yamada, S.; Kondo, H.; Takamaru, H.; Sakamoto, T.; Sese, J.; Kuchiba, A.; et al. Development of a real-time endoscopic image diagnosis support system using deep learning technology in colonoscopy. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 14465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, S.; Takasawa, K.; Asada, K.; Shiraishi, K.; Ikawa, N.; Machino, H.; Shinkai, N.; Matsuda, M.; Masuda, M.; Adachi, S.; et al. Mechanism of ERBB2 gene overexpression by the formation of super-enhancer with genomic structural abnormalities in lung adenocarcinoma without clinically actionable genetic alterations. Mol. Cancer 2024, 23, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, V.M.; Hla, M.; Moor, M.; Adithan, S.; Kwak, S.; Topol, E.J.; Rajpurkar, P. Multimodal generative AI for medical image interpretation. Nature 2025, 639, 888–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yuan, T.; Sermesant, M.; Delingette, H.; Wu, O. Mutual Information Guided Diffusion for Zero-Shot Cross-Modality Medical Image Translation. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2024, 43, 2825–2838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Li, Y.; Lu, K.; Zhang, J.; Chen, P.; Yan, K.; Wang, B. Medical Tumor Image Classification Based on Few-Shot Learning. IEEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinform. 2024, 21, 715–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiorentino, M.C.; Villani, F.P.; Di Cosmo, M.; Frontoni, E.; Moccia, S. A review on deep-learning algorithms for fetal ultrasound-image analysis. Med. Image Anal. 2023, 83, 102629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Chang, H.; Yang, D.; Yang, F.; Wang, Q.; Deng, Y.; Li, L.; Lv, W.; Zhang, B.; Yu, L.; et al. A deep learning framework assisted echocardiography with diagnosis, lesion localization, phenogrouping heterogeneous disease, and anomaly detection. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, C.F.; Kamnitsas, K.; Matthew, J.; Fletcher, T.P.; Smith, S.; Koch, L.M.; Kainz, B.; Rueckert, D. SonoNet: Real-Time Detection and Localisation of Fetal Standard Scan Planes in Freehand Ultrasound. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2017, 36, 2204–2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi, A.H.; Luong, C.; Tsang, T.; Allan, G.; Nouranian, S.; Jue, J.; Hawley, D.; Fleming, S.; Gin, K.; Swift, J.; et al. Automatic Quality Assessment of Echocardiograms Using Convolutional Neural Networks: Feasibility on the Apical Four-Chamber View. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2017, 36, 1221–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slimani, S.; Hounka, S.; Mahmoudi, A.; Rehah, T.; Laoudiyi, D.; Saadi, H.; Bouziyane, A.; Lamrissi, A.; Jalal, M.; Bouhya, S.; et al. Fetal biometry and amniotic fluid volume assessment end-to-end automation using Deep Learning. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoyama, R.; Komatsu, M.; Harada, N.; Komatsu, R.; Sakai, A.; Takeda, K.; Teraya, N.; Asada, K.; Kaneko, S.; Iwamoto, K. Automated assessment of the pulmonary artery-to-ascending aorta ratio in fetal cardiac ultrasound screening using artificial intelligence. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, L.; Luewan, S.; Romero, R. Fetal Intelligent Navigation Echocardiography (FINE) Detects 98% of Congenital Heart Disease. J. Ultrasound Med. 2018, 37, 2577–2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridge, C.P.; Ioannou, C.; Noble, J.A. Automated annotation and quantitative description of ultrasound videos of the fetal heart. Med. Image Anal. 2017, 36, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam-Rachlin, J.; Punn, R.; Behera, S.K.; Geiger, M.; Lachaud, M.; David, N.; Garmel, S.; Fox, N.S.; Rebarber, A.; DeVore, G.R.; et al. Use of Artificial Intelligence-Based Software to Aid in the Identification of Ultrasound Findings Associated With Fetal Congenital Heart Defects. Obstet. Gynecol. 2026, 147, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, Q.; Sinclair, M.; Zimmer, V.; Hou, B.; Rajchl, M.; Toussaint, N.; Oktay, O.; Schlemper, J.; Gomez, A.; Housden, J.; et al. Weakly Supervised Estimation of Shadow Confidence Maps in Fetal Ultrasound Imaging. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2019, 38, 2755–2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasutomi, S.; Arakaki, T.; Matsuoka, R.; Sakai, A.; Komatsu, R.; Shozu, K.; Dozen, A.; Machino, H.; Asada, K.; Kaneko, S.; et al. Shadow Estimation for Ultrasound Images Using Auto-Encoding Structures and Synthetic Shadows. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komatsu, M.; Sakai, A.; Komatsu, R.; Matsuoka, R.; Yasutomi, S.; Shozu, K.; Dozen, A.; Machino, H.; Hidaka, H.; Arakaki, T. Detection of cardiac structural abnormalities in fetal ultrasound videos using deep learning. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuhamad, A.Z.; Chaoui, R. A Practical Guide to Fetal Echocardiography: Normal and Abnormal Hearts; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Paladini, D.; Pistorio, A.; Wu, L.H.; Meccariello, G.; Lei, T.; Tuo, G.; Donarini, G.; Marasini, M.; Xie, H.N. Prenatal diagnosis of total and partial anomalous pulmonary venous connection: Multicenter cohort study and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 52, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo-Valenzuela, N.J.M.; Peixoto, A.B.; Araujo Júnior, E. Prenatal diagnosis of total anomalous pulmonary venous connection: 2D and 3D echocardiographic findings. J. Clin. Ultrasound 2021, 49, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, J.S.; Axt-Fliedner, R.; Chaoui, R.; Copel, J.A.; Cuneo, B.F.; Goff, D.; Gordin Kopylov, L.; Hecher, K.; Lee, W.; Moon-Grady, A.J.; et al. ISUOG practice guidelines (updated): Fetal cardiac screening. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2023, 61, 788–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myronenko, A. 3D MRI brain tumor segmentation using autoencoder regularization. In Proceedings of the International MICCAI Brainlesion Workshop, Granada, Spain, 16–20 September 2018; pp. 311–320. [Google Scholar]

- Hatamizadeh, A.; Nath, V.; Tang, Y.; Yang, D.; Roth, H.R.; Xu, D. Swin unetr: Swin transformers for semantic segmentation of brain tumors in mri images. In Proceedings of the International MICCAI Brainlesion Workshop, Strasbourg, France, 27 September–1 October 2021; pp. 272–284. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, S.; Koehler, G.; Ulrich, C.; Baumgartner, M.; Petersen, J.; Isensee, F.; Jäger, P.F.; Maier-Hein, K.H. MedNeXt: Transformer-Driven Scaling of ConvNets for Medical Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention—MICCAI 2023, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–12 October 2023; pp. 405–415. [Google Scholar]

- Perera, S.; Navard, P.; Yilmaz, A. Segformer3d: An efficient transformer for 3d medical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 17–21 June 2024; pp. 4981–4988. [Google Scholar]

- Kao, C.C.; Hsieh, C.C.; Cheng, P.J.; Chiang, C.H.; Huang, S.Y. Total Anomalous Pulmonary Venous Connection: From Embryology to a Prenatal Ultrasound Diagnostic Update. J. Med. Ultrasound 2017, 25, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degenhardt, K.; Singh, M.K.; Aghajanian, H.; Massera, D.; Wang, Q.; Li, J.; Li, L.; Choi, C.; Yzaguirre, A.D.; Francey, L.J.; et al. Semaphorin 3d signaling defects are associated with anomalous pulmonary venous connections. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 760–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tongsong, T.; Luewan, S.; Jatavan, P.; Tongprasert, F.; Sukpan, K. A Simple Rule for Prenatal Diagnosis of Total Anomalous Pulmonary Venous Return. J. Ultrasound Med. 2016, 35, 1601–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chih, W.L.; Ko, H.; Chang, T.Y. Prenatal Ultrasound Markers of Isolated Total Anomalous Pulmonary Venous Return and a Sequential Approach to Reach Diagnosis. J. Med. Ultrasound 2024, 32, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawazu, Y.; Inamura, N.; Shiono, N.; Kanagawa, N.; Narita, J.; Hamamichi, Y.; Kayatani, F. ‘Post-LA space index’ as a potential novel marker for the prenatal diagnosis of isolated total anomalous pulmonary venous connection. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2014, 44, 682–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawazu, Y.; Inamura, N.; Kayatani, F.; Taniguchi, T. Evaluation of the post-LA space index in the normal fetus. Prenat. Diagn. 2019, 39, 195–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anuwutnavin, S.; Unalome, V.; Rekhawasin, T.; Tongprasert, F.; Thongkloung, P. Fetal left-atrial posterior-space-to-diagonal ratio at 17-37 weeks’ gestation for prediction of total anomalous pulmonary venous connection. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2023, 61, 488–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chen, H.; Zhu, F.; Wen, C.; Chen, H.; Wang, L. Automatic Pulmonary Vein and Left Atrium Segmentation for TAPVC Preoperative Evaluation Using V-Net with Grouped Attention. In Proceedings of the 2020 42nd Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC), Montreal, QC, Canada, 20–24 July 2020; pp. 1207–1210. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Yang, T.Y.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Liu, X.W.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, L.; Gu, X.Y.; Chen, Z.; Guo, Y.; Xue, C.; et al. Diagnosis of fetal total anomalous pulmonary venous connection based on the post-left atrium space ratio using artificial intelligence. Prenat. Diagn. 2022, 42, 1323–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | Normal Cases | TAPVC Cases | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mDice | HD95 | mDice | HD95 | |

| SegResNet | 0.784 | 5.12 | 0.443 | 17.7 |

| Swin UNETR | 0.738 | 9.72 | 0.323 | 28.8 |

| MedNeXt | 0.765 | 6.36 | 0.448 | 23.3 |

| SegFormer3D | 0.713 | 8.11 | 0.563 | 8.49 |

| Model | Normal Cases | TAPVC Cases | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLD | PLA | PLD | PLA | |||||

| Mean ± SD | MAE | Mean ± SD | MAE | Mean ± SD | MAE | Mean ± SD | MAE | |

| SegResNet | 1.19 ± 0.281 | 0.185 | 38.6 ± 15.8 | 8.24 | 1.31 ± 0.289 | 1.33 | 57.4 ± 9.26 | 14.4 |

| Swin UNETR | 1.78 ± 2.43 | 0.779 | 43.2 ± 16.0 | 9.71 | 4.22 ± 6.10 | 3.39 | 51.1 ± 12.0 | 15.9 |

| MedNeXt | 1.23 ± 0.420 | 0.223 | 40.6 ± 18.8 | 9.10 | 5.15 ± 9.35 | 3.81 | 48.2 ± 15.7 | 13.4 |

| SegFormer3D | 1.94 ± 2.75 | 0.941 | 47.3 ± 13.0 | 10.7 | 2.07 ± 1.37 | 1.35 | 43.4 ± 13.2 | 14.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Komatsu, R.; Komatsu, M.; Takeda, K.; Harada, N.; Teraya, N.; Wakisaka, S.; Natsume, T.; Taniguchi, T.; Aoyama, R.; Kaneko, M.; et al. Three-Dimensional Visualization and Detection of the Pulmonary Venous–Left Atrium Connection Using Artificial Intelligence in Fetal Cardiac Ultrasound Screening. Bioengineering 2026, 13, 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering13010100

Komatsu R, Komatsu M, Takeda K, Harada N, Teraya N, Wakisaka S, Natsume T, Taniguchi T, Aoyama R, Kaneko M, et al. Three-Dimensional Visualization and Detection of the Pulmonary Venous–Left Atrium Connection Using Artificial Intelligence in Fetal Cardiac Ultrasound Screening. Bioengineering. 2026; 13(1):100. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering13010100

Chicago/Turabian StyleKomatsu, Reina, Masaaki Komatsu, Katsuji Takeda, Naoaki Harada, Naoki Teraya, Shohei Wakisaka, Takashi Natsume, Tomonori Taniguchi, Rina Aoyama, Mayumi Kaneko, and et al. 2026. "Three-Dimensional Visualization and Detection of the Pulmonary Venous–Left Atrium Connection Using Artificial Intelligence in Fetal Cardiac Ultrasound Screening" Bioengineering 13, no. 1: 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering13010100

APA StyleKomatsu, R., Komatsu, M., Takeda, K., Harada, N., Teraya, N., Wakisaka, S., Natsume, T., Taniguchi, T., Aoyama, R., Kaneko, M., Iwamoto, K., Matsuoka, R., Sekizawa, A., & Hamamoto, R. (2026). Three-Dimensional Visualization and Detection of the Pulmonary Venous–Left Atrium Connection Using Artificial Intelligence in Fetal Cardiac Ultrasound Screening. Bioengineering, 13(1), 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering13010100