A Speech-Based Mobile Screening Tool for Mild Cognitive Impairment: Technical Performance and User Engagement Evaluation

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Objectives

1.3. Research Questions and Hypotheses for User Engagement Study

2. Methods

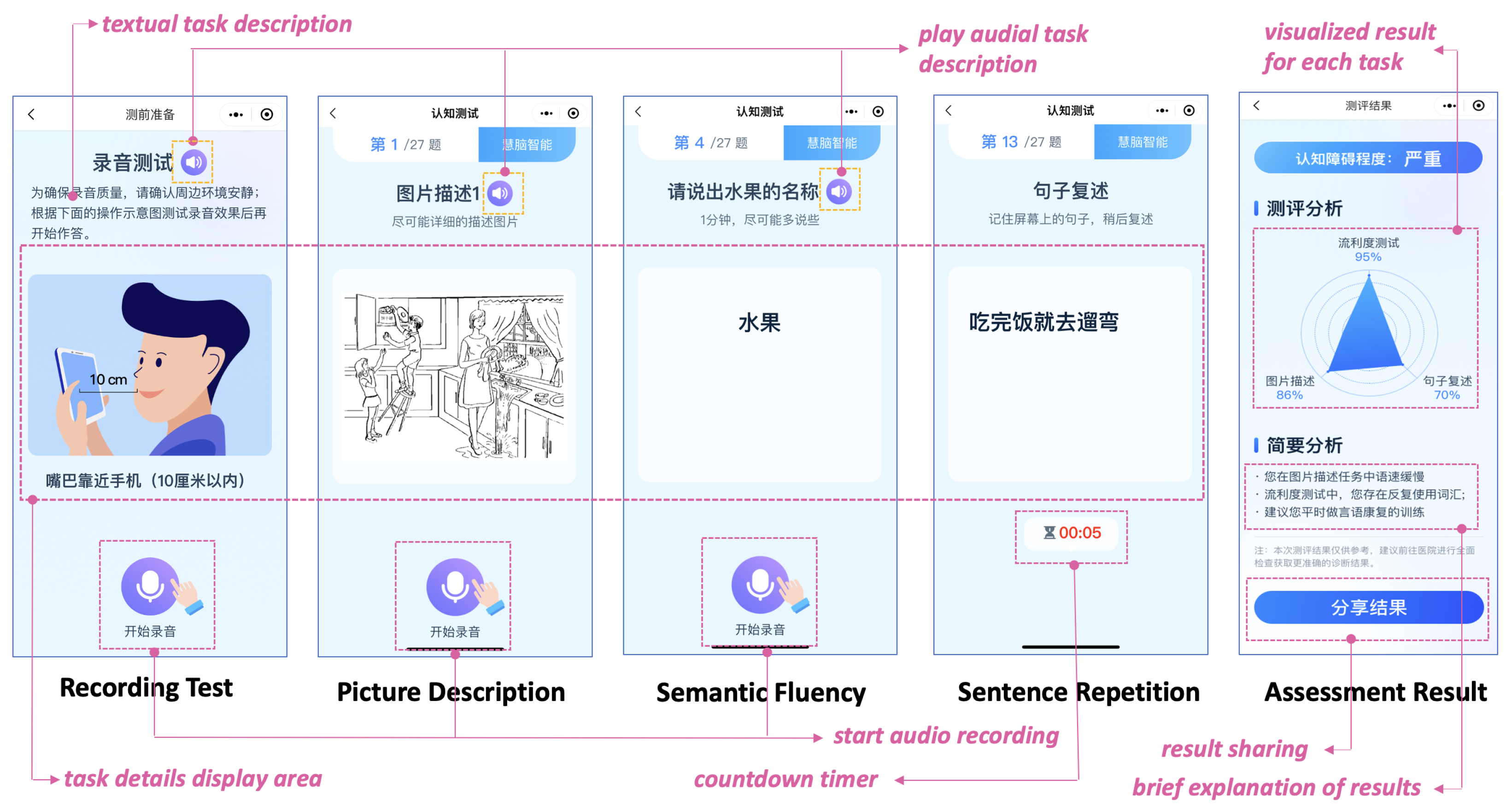

2.1. Mobile App Design

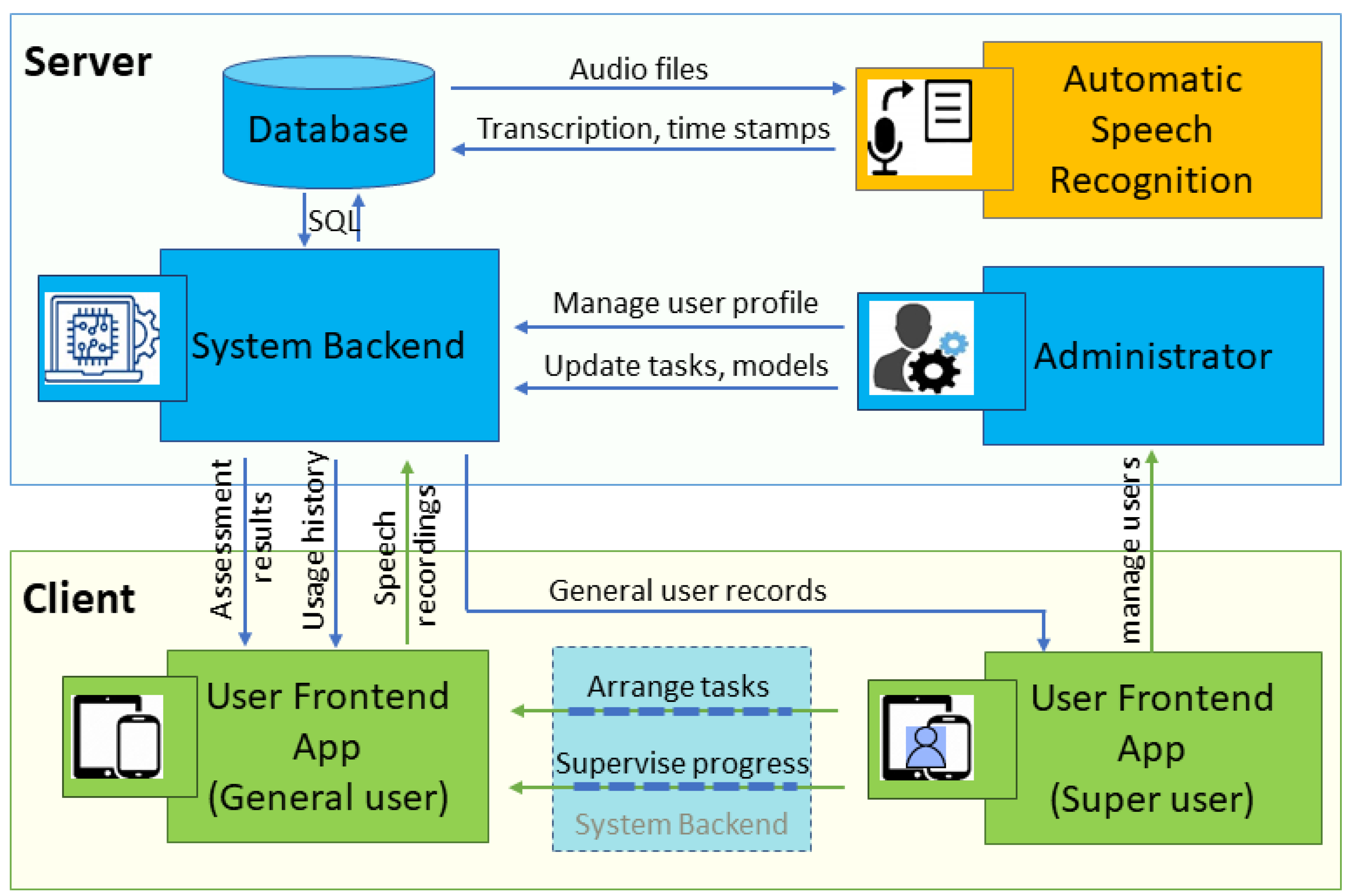

2.1.1. App Architecture and Development Framework

2.1.2. Security Considerations and Data Protection

2.1.3. User-Centered Design Principles

2.1.4. Speech Tasks, Feature Extraction, and Classification

2.2. User Engagement Study Procedure

- (1)

- Cognitive processing (thinking/analyzing), defined as observable focused or engaged behavior, such as short pauses during speech without obvious distraction or stops to produce words described in filled pauses;

- (2)

- Distraction levels, defined as observable distracted behaviors, such as looking away from the screen, engaging in task-irrelevant speech, or engaging in body movements unrelated to the task.

2.3. Performance Metrics and Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participants

3.2. MCI Detection Performance

3.2.1. Comparison with Manual Assessment

3.2.2. Real-World Dataset Evaluation

3.3. User Engagement Findings

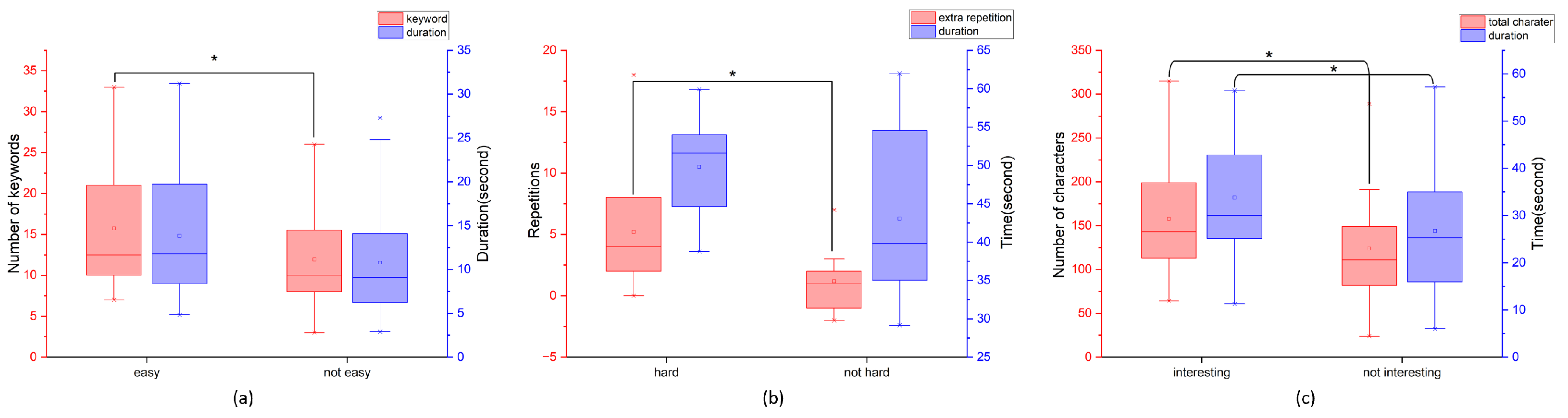

3.3.1. Overall App Difficulty Perception and Cognitive Performance

3.3.2. Task-Specific Engagement Patterns

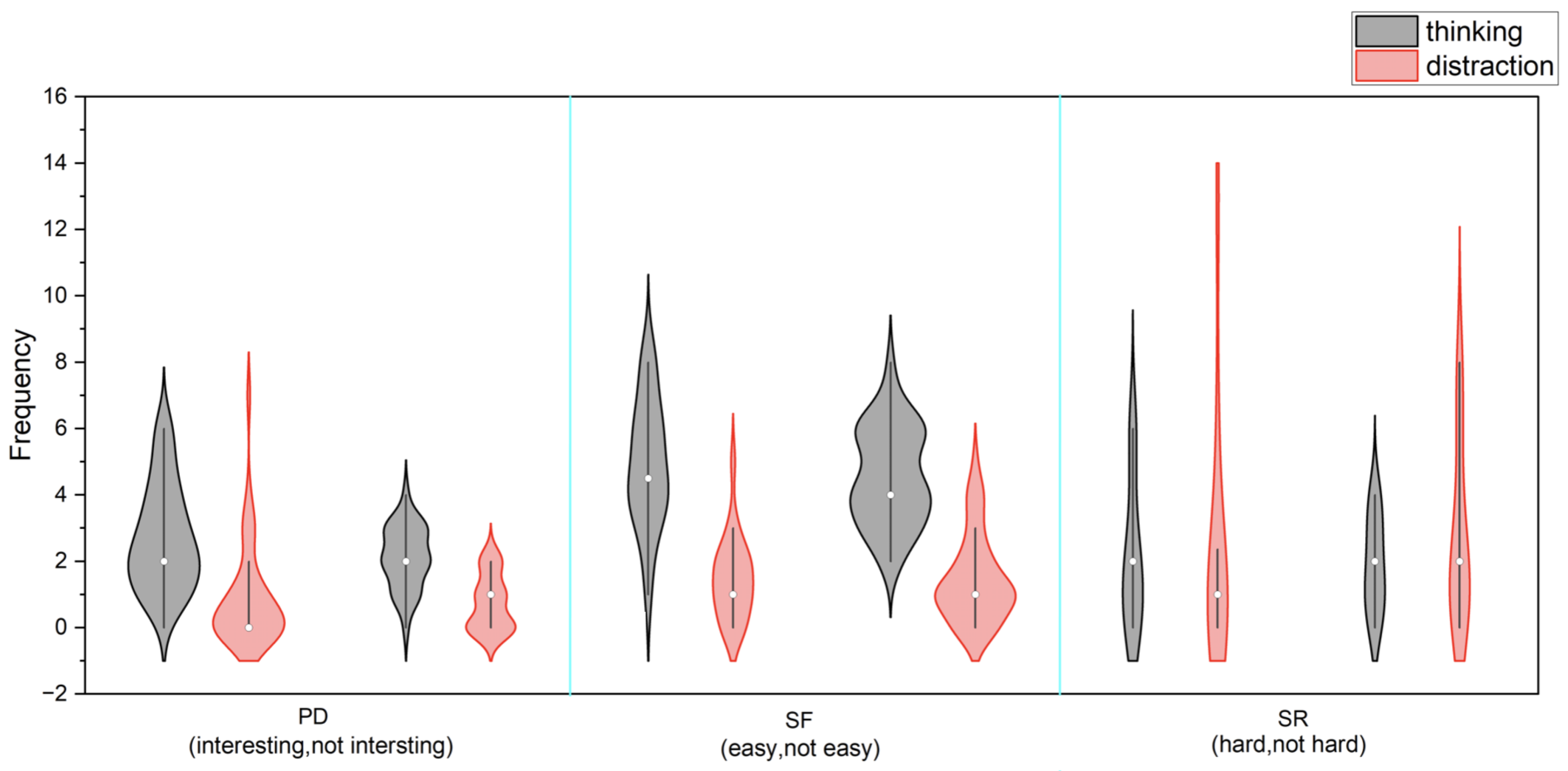

3.3.3. Behavioral Observations and Task Engagement

3.3.4. Daily Habits, Perceived Benefits, and Technology Adoption

4. Discussion

4.1. Overview

4.2. Principal Findings

4.3. Clinical Integration Potential

4.4. Limitations and Future Work

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arnáiz, E.; Almkvist, O. Neuropsychological Features of Mild Cognitive Impairment and Preclinical Alzheimer’s Disease. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2003, 107, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, S.B. Cognition-Based Interventions for Healthy Older People and People with Mild Cognitive Impairment. Clin. Nurse Spec. 2011, 25, 178–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knopman, D.S.; Amieva, H.; Petersen, R.C.; Chételat, G.; Holtzman, D.M.; Hyman, B.T.; Nixon, R.A.; Jones, D.T. Alzheimer Disease. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2021, 7, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheltens, P.; De Strooper, B.; Kivipelto, M.; Holstege, H.; Chételat, G.; Teunissen, C.E.; Cummings, J.; van der Flier, W.M. Alzheimer’s Disease. Lancet 2021, 397, 1577–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapkota, S.; Huan, T.; Tran, T.; Zheng, J.; Camicioli, R.; Li, L.; Dixon, R.A. Alzheimer’s Biomarkers from Multiple Modalities Selectively Discriminate Clinical Status: Relative Importance of Salivary Metabolomics Panels, Genetic, Lifestyle, Cognitive, Functional Health, and Demographic Risk Markers. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2018, 10, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, L.; Du, Y.; Chu, L.; Zhang, Z.; Li, F.; Lyu, D.; Li, Y.; Zhu, M.; Jiao, H.; Song, Y.; et al. Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Management of Dementia and Mild Cognitive Impairment in Adults Aged 60 Years or Older in China: A Cross-Sectional Study. Lancet Public Health 2020, 5, e661–e671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, R.; Qi, J.; Lin, S.; Liu, X.; Yin, P.; Wang, Z.; Tang, R.; Wang, J.; Huang, Q.; Li, J.; et al. The China Alzheimer Report 2022. Gen. Psychiatry 2022, 35, e100751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kam, T.E.; Zhang, H.; Jiao, Z.; Shen, D. Deep Learning of Static and Dynamic Brain Functional Networks for Early MCI Detection. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2019, 39, 478–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Y.; Gu, Z.X.; Wei, W.S. Fluorodeoxyglucose-Positron Emission Tomography, Single-Photon Emission Tomography, and Structural MR Imaging for Prediction of Rapid Conversion to Alzheimer’s Disease in Patients with Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2009, 30, 404–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herholz, K.; Carter, S.; Jones, M. Positron Emission Tomography Imaging in Dementia. Br. J. Radiol. 2007, 80, S160–S167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritchie, C.; Noel-Storr, A.H.; Ukoumunne, O.; Ladds, E.C.; Martin, S. CSF Tau and the CSF Tau/ABeta Ratio for the Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease Dementia and Other Dementias in People with Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI). Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herukka, S.K.; Simonsen, A.H.; Andreasen, N.; Baldeiras, I.; Bjerke, M.; Blennow, K.; Engelborghs, S.; Frisoni, G.B.; Gabryelewicz, T.; Galluzzi, S.; et al. Recommendations for Cerebrospinal Fluid Alzheimer’s Disease Biomarkers in the Diagnostic Evaluation of Mild Cognitive Impairment. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2017, 13, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfsgruber, S.; Polcher, A.; Koppara, A.; Kleineidam, L.; Frölich, L.; Peters, O.; Hüll, M.; Rüther, E.; Wiltfang, J.; Maier, W.; et al. Cerebrospinal Fluid Biomarkers and Clinical Progression in Patients with Subjective Cognitive Decline and Mild Cognitive Impairment. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2017, 58, 939–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasreddine, Z.S.; Phillips, N.A.; Bédirian, V.; Charbonneau, S.; Whitehead, V.; Collin, I.; Cummings, J.L.; Chertkow, H. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA): A Brief Screening Tool for Mild Cognitive Impairment. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2005, 53, 695–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arevalo-Rodriguez, I.; Smailagic, N.; i Figuls, M.R.; Ciapponi, A.; Sanchez-Perez, E.; Giannakou, A.; Pedraza, O.L.; Cosp, X.B.; Cullum, S. Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) for the Detection of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias in People with Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI). Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, A.T.; Lee, G.J. Cognitive Screening for Early Detection of Mild Cognitive Impairment. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2020, 32, 1015–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, L.; Yang, Y.; Gao, J. Cognitive Assessment Tools for Mild Cognitive Impairment Screening. J. Neurol. 2021, 268, 1615–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Li, Y.; Wu, J.; Chen, N.; Xia, H.; Guo, Q. Shanghai Cognitive Screening: A Mobile Cognitive Assessment Tool Using Voice Recognition to Detect Mild Cognitive Impairment and Dementia in the Community. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2023, 95, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voleti, R.; Liss, J.M.; Berisha, V. A Review of Automated Speech and Language Features for Assessment of Cognitive and Thought Disorders. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Signal Process. 2019, 14, 282–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschi, V.; Catricala, E.; Consonni, M.; Chesi, C.; Moro, A.; Cappa, S.F. Connected Speech in Neurodegenerative Language Disorders: A Review. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Kuang, C.; Guo, C.; Chen, Y.; Li, C.; Matsumura, Y.; Ishimaru, M.; Van Pelt, A.J.; Chen, F. Automatic Detection of Putative Mild Cognitive Impairment from Speech Acoustic Features in Mandarin-Speaking Elders. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2023, 95, 901–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, Y.; Xie, X.Y.; Lin, G.Z.; Zou, Y.; Chen, S.D.; Ren, R.J.; Wang, G. Computer-Assisted Speech Analysis in Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer’s Disease: A Pilot Study from Shanghai, China. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2020, 75, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostrand, R.; Gunstad, J. Using Automatic Assessment of Speech Production to Predict Current and Future Cognitive Function in Older Adults. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 2021, 34, 357–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanborn, V.; Ostrand, R.; Ciesla, J.; Gunstad, J. Automated Assessment of Speech Production and Prediction of MCI in Older Adults. Appl. Neuropsychol. Adult 2022, 29, 1250–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Malley, R.P.D.; Mirheidari, B.; Harkness, K.; Reuber, M.; Venneri, A.; Walker, T.; Christensen, H.; Blackburn, D. Fully Automated Cognitive Screening Tool Based on Assessment of Speech and Language. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2021, 92, 12–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, G.; Morris, L.A.; Christensen, H.; Mirheidari, B.; Reuber, M.; Blackburn, D.J. Characterizing Spoken Responses to an Intelligent Virtual Agent by Persons with Mild Cognitive Impairment. Clin. Linguist. Phon. 2021, 35, 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirheidari, B.; Blackburn, D.; O’Malley, R.; Walker, T.; Venneri, A.; Reuber, M.; Christensen, H. Computational Cognitive Assessment: Investigating the Use of an Intelligent Virtual Agent for the Detection of Early Signs of Dementia. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2019—2019 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Brighton, UK, 12–17 May 2019 ; pp. 2732–2736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouzuki, M.; Miyamoto, M.; Tanaka, N.; Urakami, K. Validation of a Novel Computerized Cognitive Function Test for the Rapid Detection of Mild Cognitive Impairment. BMC Neurol. 2022, 22, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeent, S.; Spaltman, M.; van Elswijk, G.; Miller, J.B.; Schmand, B. Philips IntelliSpace Cognition Digital Test Battery: Equivalence and Measurement Invariance Compared to Traditional Analog Test Versions. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2022, 36, 2278–2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moses, J.C.; Adibi, S.; Wickramasinghe, N.; Nguyen, L.; Angelova, M.; Islam, S.M.S. Smartphone as a Disease Screening Tool: A Systematic Review. Sensors 2022, 22, 3787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osei, E.; Mashamba-Thompson, T.P. Mobile Health Applications for Disease Screening and Treatment Support in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Narrative Review. Heliyon 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghu, A.; Praveen, D.; Peiris, D.; Tarassenko, L.; Clifford, G. Engineering a Mobile Health Tool for Resource-Poor Settings to Assess and Manage Cardiovascular Disease Risk: SMARThealth Study. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2015, 15, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thabtah, F.; Peebles, D.; Retzler, J.; Hathurusingha, C. Dementia Medical Screening Using Mobile Applications: A Systematic Review with a New Mapping Model. J. Biomed. Inform. 2020, 111, 103573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Chu, X.; Teng, B.; Gao, H. A Complete Scheme for Multi-Character Classification Using EEG Signals from Speech Imagery. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2024, 71, 2454–2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalafatis, C.; Modarres, M.H.; Apostolou, P.; Marefat, H.; Khanbagi, M.; Karimi, H.; Vahabi, Z.; Aarsland, D.; Khaligh-Razavi, S.M. Validity and Cultural Generalizability of a 5-Minute AI-Based, Computerized Cognitive Assessment in Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer’s Dementia. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 706695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Hu, R.; Wen, H.; Xu, G.; Pang, T.; He, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, C.; Wu, X.; et al. A Voice Recognition-Based Digital Cognitive Screener for Dementia Detection in the Community: Development and Validation Study. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 899729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piau, A.; Wild, K.; Mattek, N.; Kaye, J. Current State of Digital Biomarker Technologies for Real-Life, Home-Based Monitoring of Cognitive Function for Mild Cognitive Impairment to Mild Alzheimer Disease and Implications for Clinical Care: Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e12785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wildenbos, G.A.; Peute, L.; Jaspers, M. Aging Barriers Influencing Mobile Health Usability for Older Adults: A Literature-Based Framework (MOLD-US). Int. J. Med. Inform. 2018, 114, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wildenbos, G.A.; Jaspers, M.W.; Schijven, M.P.; Dusseljee-Peute, L. Mobile Health for Older Adult Patients: Using an Aging Barriers Framework to Classify Usability Problems. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2019, 124, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Hong, Y.; Wang, Q.; Su, R.; Ng, M.L.; Xu, J.; Wang, L.; Yan, N. Identification of Mild Cognitive Impairment Among Chinese Based on Multiple Spoken Tasks. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2021, 82, 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, F.; Yang, P.; Du, H.; Li, X.Y. Accuth+: Accelerometer-Based Anti-Spoofing Voice Authentication on Wrist-Worn Wearables. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2023, 23, 5571–5588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangari, G.; Ikram, M.; Sentana, I.W.B.; Ijaz, K.; Kaafar, M.A.; Berkovsky, S. Analyzing Security Issues of Android Mobile Health and Medical Applications. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2021, 28, 2074–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papageorgiou, A.; Strigkos, M.; Politou, E.; Alepis, E.; Solanas, A.; Patsakis, C. Security and Privacy Analysis of Mobile Health Applications: The Alarming State of Practice. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 9390–9403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodglass, H.; Kaplan, E. Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination Booklet; Lea & Febiger: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Hameister, I.; Nickels, L. The cat in the tree–using picture descriptions to inform our understanding of conceptualisation in aphasia. Lang. Cogn. Neurosci. 2018, 33, 1296–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kertesz, A. Western Aphasia Battery-Revised; The Psychological Corporation: San Antonio, TX, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, J. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1810.04805. [Google Scholar]

- Kruskal, W.H.; Wallis, W.A. Use of Ranks in One-Criterion Variance Analysis. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1952, 47, 583–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, H.B.; Whitney, D.R. On a Test of Whether One of Two Random Variables is Stochastically Larger Than the Other. Ann. Math. Stat. 1947, 18, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Nicolás, I.; Llorente, T.E.; Martínez-Sánchez, F.; Meilán, J.J.G. Ten Years of Research on Automatic Voice and Speech Analysis of People with Alzheimer’s Disease and Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Systematic Review Article. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 620251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhard, M.A.; Dickhäuser, O. Need for Cognition, Task Difficulty, and the Formation of Performance Expectancies. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 96, 1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahlevanynejad, S.; Niakan Kalhori, S.R.; Katigari, M.R.; Eshpala, R.H. Personalized Mobile Health for Elderly Home Care: A Systematic Review of Benefits and Challenges. Int. J. Telemed. Appl. 2023, 2023, 5390712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Manual | Automatic | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tasks | Acc | Pre | Rec | F1 | Acc | Pre | Rec | F1 |

| SR | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.91 | 0.87 | 0.94 | 0.90 |

| SF | 0.71 | 0.74 | 0.56 | 0.64 | 0.79 | 0.75 | 0.82 | 0.78 |

| PD(Custom) | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.84 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.74 | 0.86 | 0.80 |

| PD(BERT) | - | - | - | - | 0.79 | 0.75 | 0.82 | 0.78 |

| Task fusion | 0.95 | 0.97 | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.91 | 0.96 | 0.93 |

| Task | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SR | 0.67 | 0.60 | 1.00 | 0.75 |

| SF | 0.58 | 0.67 | 0.33 | 0.44 |

| PD (Custom features) | 0.42 | 0.43 | 0.50 | 0.46 |

| PD (BERT features) | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.67 | 0.57 |

| Task fusion | 0.83 | 0.75 | 1.00 | 0.86 |

| Overall Perception Median M() | Kruskal–Wallis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difficult (n = 7) | Just ok (n = 7) | Easy (n = 3) | H | p | |

| MoCA | 28 (26, 29) | 25 (22, 28) | 29 (29, 29) | 4.256 | 0.119 |

| Prob.MCI | 0.456 (0.3, 0.6) | 0.470 (0.4, 0.5) | 0.297 (0.2, 0.5) | 2.387 | 0.303 |

| Education | Daily Habit | |

|---|---|---|

| Benefit Valuation | H = 7.035 | H = 9.385 ** |

| Technology Acceptance | H = 7.770 | H = 0.762 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ruzi, R.; Pan, Y.; Ng, M.L.; Su, R.; Wang, L.; Dang, J.; Liu, L.; Yan, N. A Speech-Based Mobile Screening Tool for Mild Cognitive Impairment: Technical Performance and User Engagement Evaluation. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering12020108

Ruzi R, Pan Y, Ng ML, Su R, Wang L, Dang J, Liu L, Yan N. A Speech-Based Mobile Screening Tool for Mild Cognitive Impairment: Technical Performance and User Engagement Evaluation. Bioengineering. 2025; 12(2):108. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering12020108

Chicago/Turabian StyleRuzi, Rukiye, Yue Pan, Menwa Lawrence Ng, Rongfeng Su, Lan Wang, Jianwu Dang, Liwei Liu, and Nan Yan. 2025. "A Speech-Based Mobile Screening Tool for Mild Cognitive Impairment: Technical Performance and User Engagement Evaluation" Bioengineering 12, no. 2: 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering12020108

APA StyleRuzi, R., Pan, Y., Ng, M. L., Su, R., Wang, L., Dang, J., Liu, L., & Yan, N. (2025). A Speech-Based Mobile Screening Tool for Mild Cognitive Impairment: Technical Performance and User Engagement Evaluation. Bioengineering, 12(2), 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering12020108