The Role of MER Processing Pipelines for STN Functional Identification During DBS Surgery: A Feature-Based Machine Learning Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Dataset

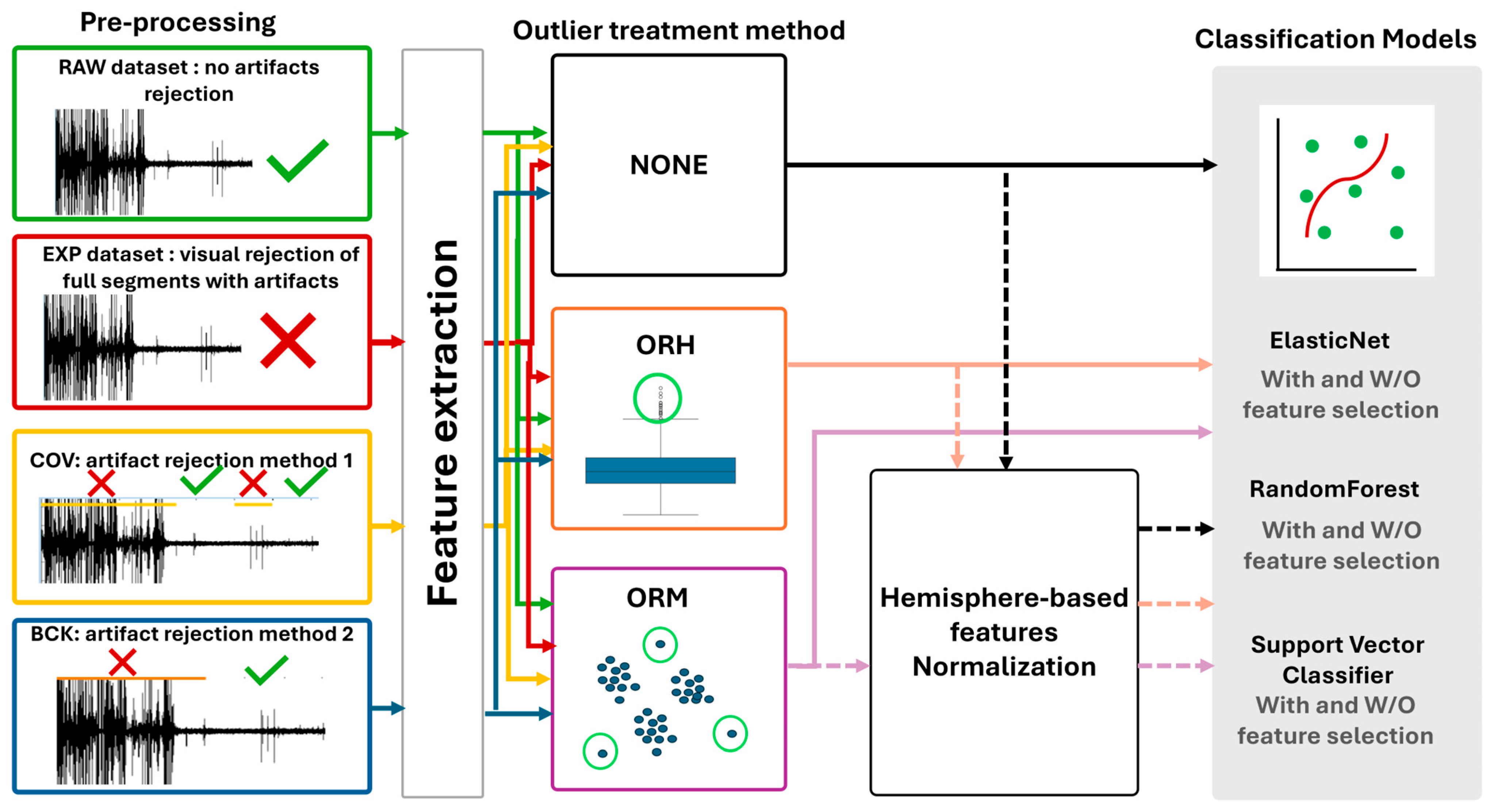

2.2. Dataset Preparation Pipelines

2.2.1. Data Preparation and Preprocessing

- Segmentation of the signal into m 0.5 s segments

- Compute the autocorrelation of each segment

- Compute the variance of the transformed segment ;

- Comparison of the variances of neighboring segments by computing their distance as ;

- Creation of a distance matrix of all possible distances between segment pairs;

- The matrix elements exceeding an experimentally identified threshold (Th = 1.8) are replaced with ones and others are replaced with zeros, and an adjacency matrix is obtained;

- The resulting matrix is scanned for the longest uninterrupted segment (sequence of zeros) using a greedy algorithm.

2.2.2. Feature Extraction

2.2.3. Outlier Detection and Management

- (a)

- NONE—the first simple possibility is not to apply any outlier detection.

- (b)

- Outlier Rejection for Hemisphere (ORH) of each patient set, the classic approach based on feature distribution to remove samples according to lower and upper bound (interquartile range—IQR) identification with a tolerance of three [21].

- (c)

- Outlier Rejection Model (ORM) based on machine learning methodologies, i.e., the local outlier factor algorithm (LOF), an unsupervised-based algorithm which computes the local density deviation of a given data point with respect to its neighbors, applied on single patient’s data [22].

2.2.4. Dataset Normalization

| Feature | Definition |

|---|---|

| WL—Wave or Curve length | |

| ZC—Zero crossing | The number of times the signal crosses the threshold calculated by estimating the noise level of the signal |

| PKS—Peaks | Number of positive peaks identified in a signal segment normalized for the segment length. |

| MAV—Mean value of the absolute amplitude | |

| MED—Median value of absolute amplitude | Middle value separating the greater and lower halves of the ordered absolute amplitude of the trace |

| TH—Signal threshold | |

| Root mean square (RMS) of the signal | |

| AKUR—Amplitude distribution kurtosis | |

| ASKW—Amplitude distribution skewness | |

| NL—Noise level [15,16] | Derived from the signal’s analytic envelope |

| PWRA—Averaged Power | |

| ANE—Average non-linear energy [23] | |

| powVHFrel_1 | Relative power in the 300–1000 Hz frequency range |

| powVHFrel_2 | Relative power in the 1000–2000 Hz frequency range |

| powVHFrel_3 | Relative power in the 2000–3000 Hz frequency range |

| powHFrel_1 | Relative power in the 70–220 Hz frequency range |

| powHFrel_2 | Relative power in the 220–320 Hz frequency range |

| powLFrel_1 | Relative power in the 1–4 Hz frequency range |

| powLFrel_2 | Relative power in the 4–8 Hz frequency range |

| powLFrel_3 | Relative power in the 8–13 Hz frequency range |

| powLFrel_4 | Relative power in the 13–30 Hz frequency range |

| powLFrel_5 | Relative power in the 30–70 Hz frequency range |

2.3. Classification Models

Performance Evaluation

3. Results

3.1. Preprocessing Results: Datasets’ Composition

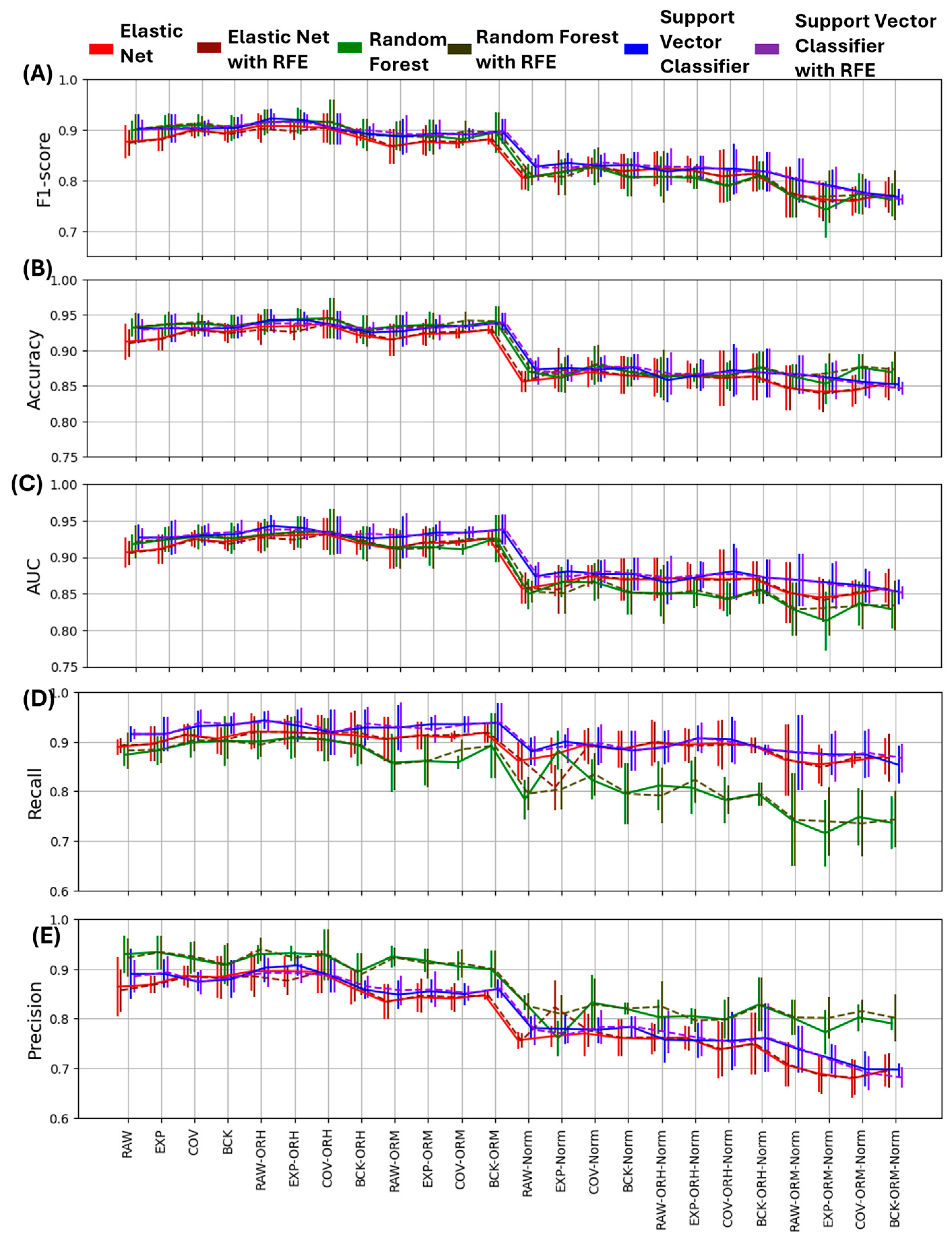

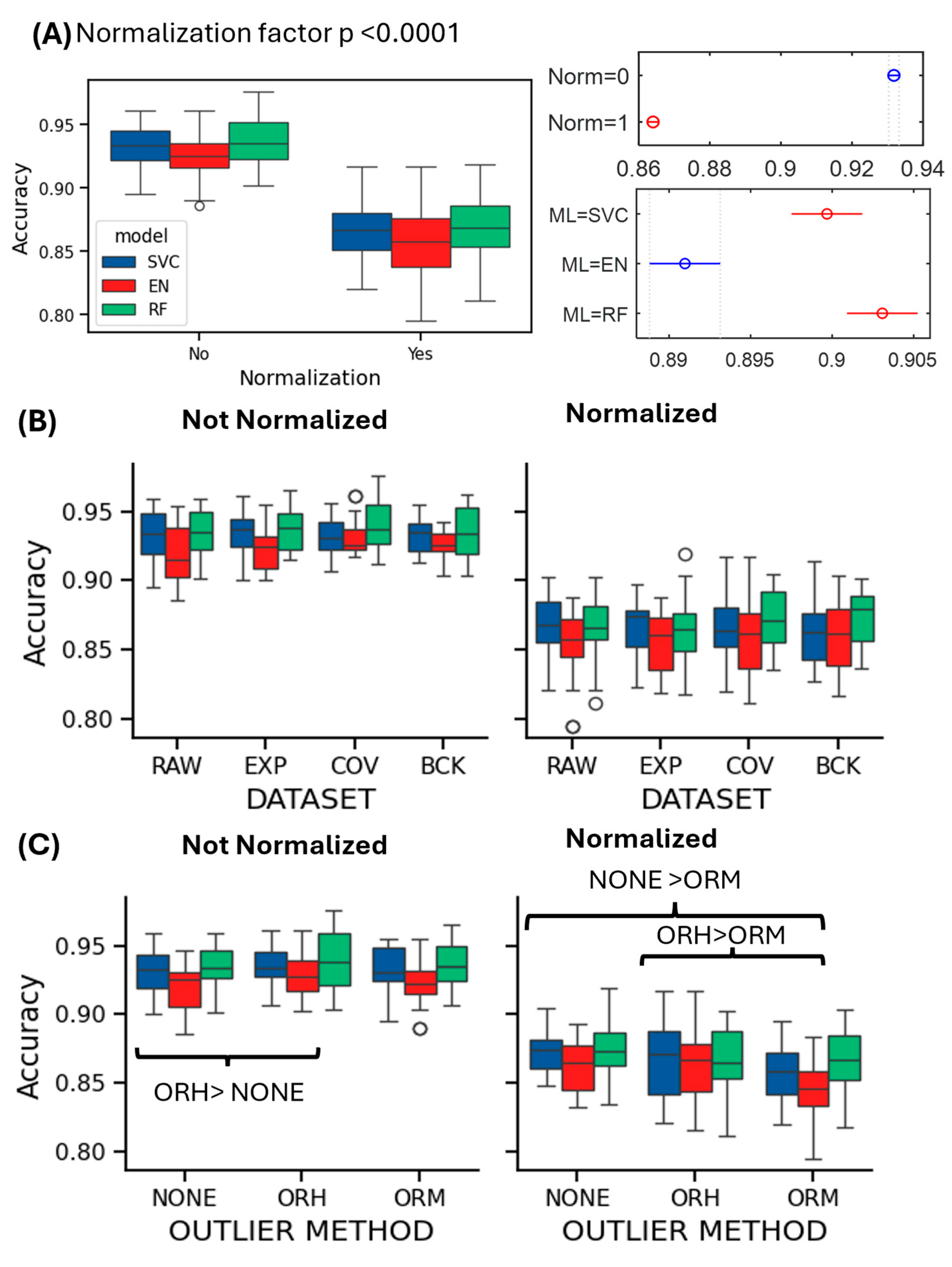

3.2. Effect of Processing Pipelines on Performance Evaluation

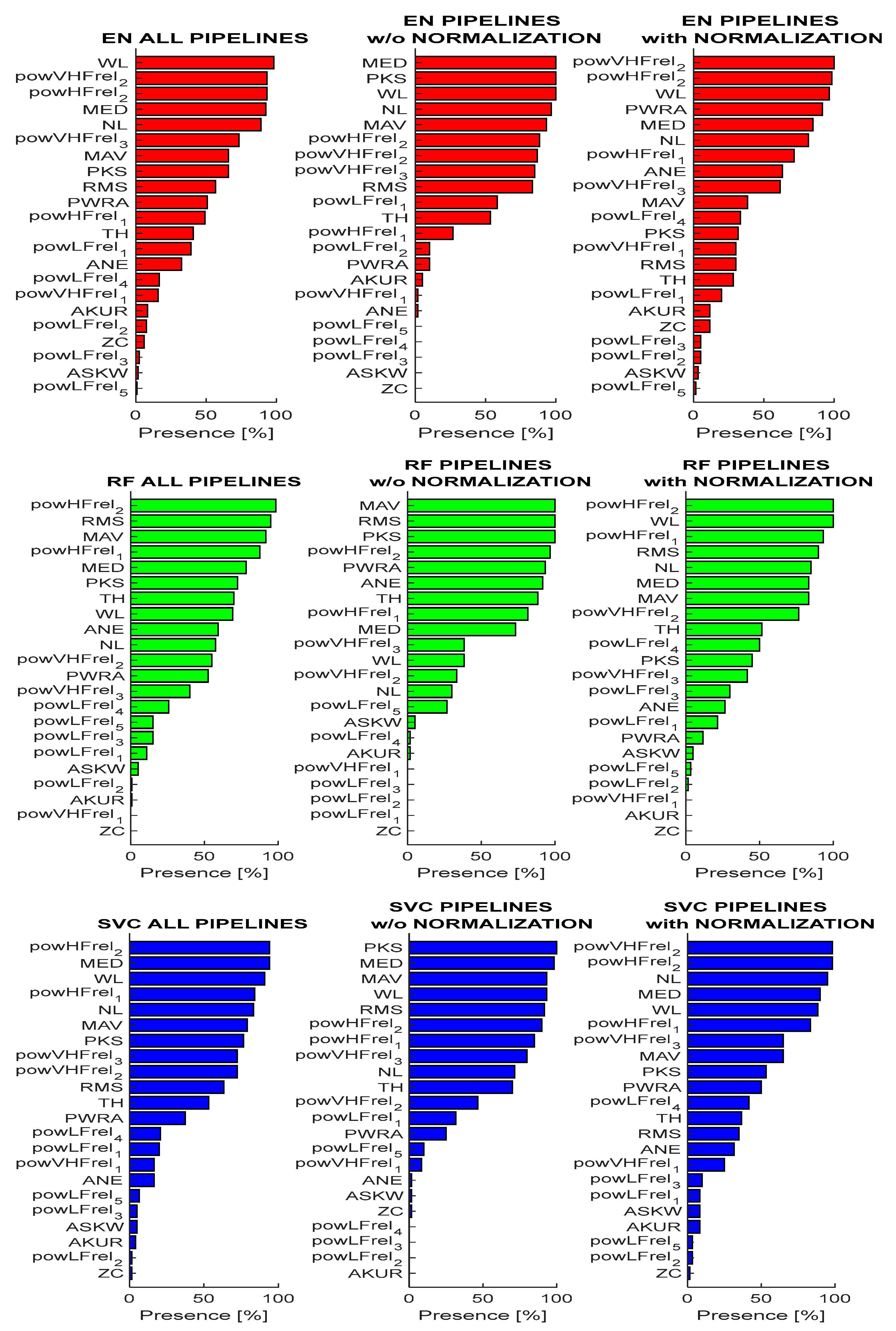

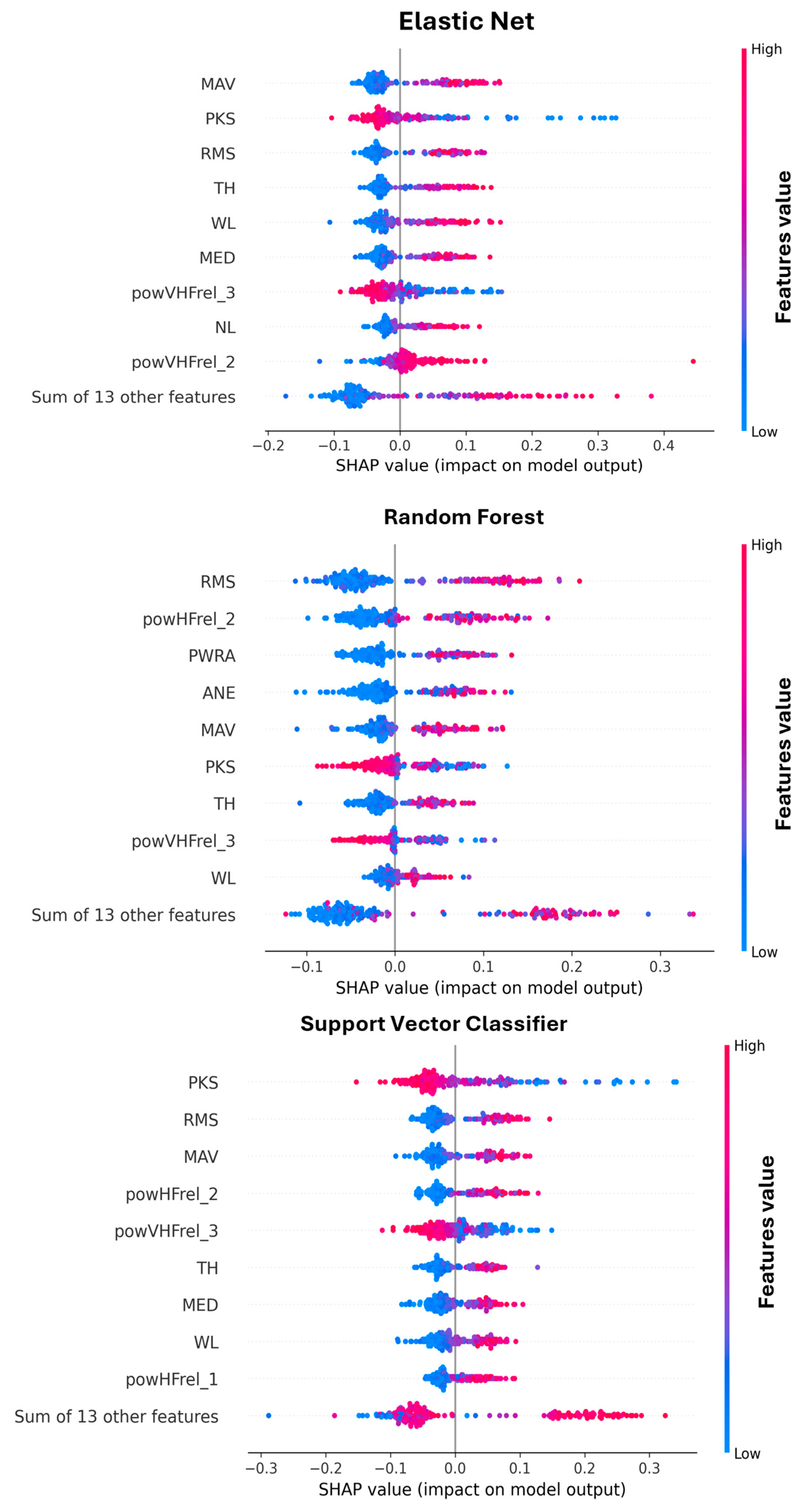

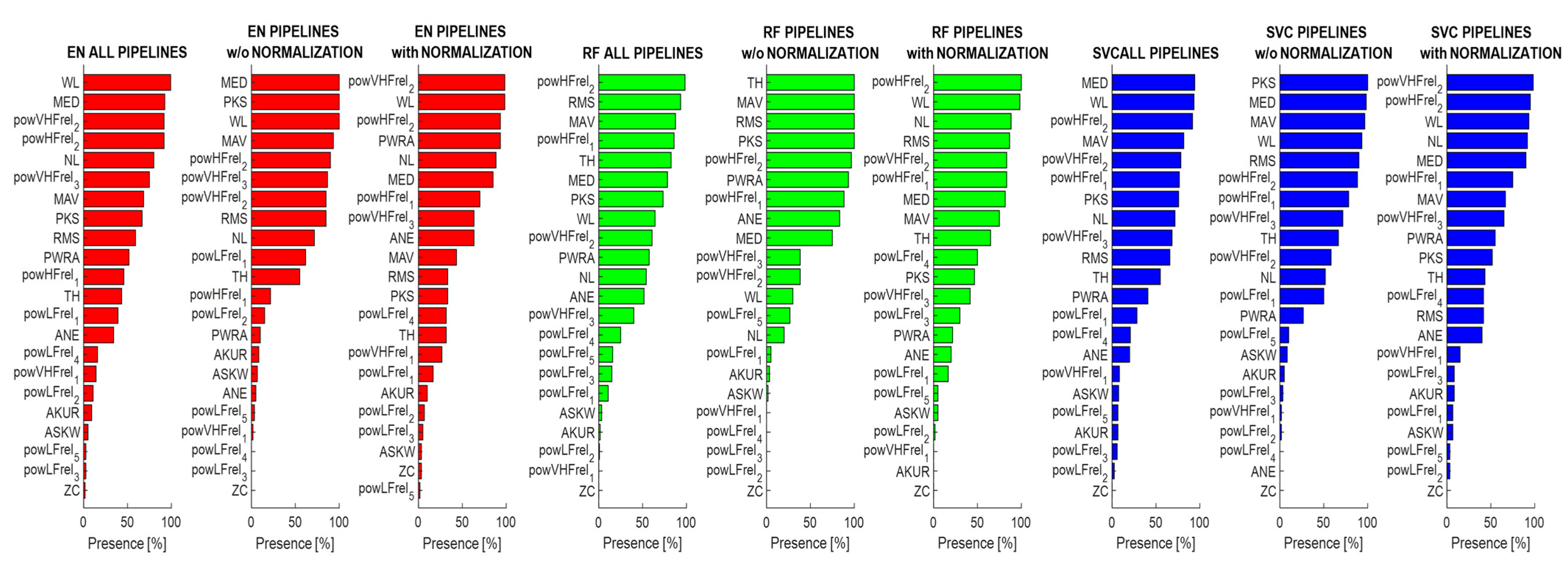

3.3. Analysis of Feature Importance

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DBS | Deep brain stimulation |

| STN | Subthalamic nucleus |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| MER | Microelectrode recording |

| ML | Machine learning |

| SHAP | SHapley Additive exPlanations |

| CT | Computed tomography |

| EDT | Estimated distance from the target |

| EXP | Expert |

References

- Kremer, N.I.; van Laar, T.; Lange, S.F.; Muller, S.S.; Gemert, S.l.B.-V.; Oterdoom, D.M.; Drost, G.; van Dijk, J.M.C. STN-DBS electrode placement accuracy and motor improvement in Parkinson’s disease: Systematic review and individual patient meta-analysis. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2023, 94, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Munckhof, P.; Bot, M.; Schuurman, P.R. Targeting of the Subthalamic Nucleus in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease Undergoing Deep Brain Stimulation Surgery. Neurol. Ther. 2021, 10, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinke, R.S.; Geerlings, M.; Selvaraj, A.K.; Georgiev, D.; Bloem, B.R.; Esselink, R.A.; Bartels, R.H. The Role of Microelectrode Recording in Deep Brain Stimulation Surgery for Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Parkinsons Dis. 2022, 12, 2059–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakharov, N.; Belova, E.; Gamaleya, A.; Tomskiy, A.; Sedov, A. Neuronal activity features of the subthalamic nucleus associated with optimal deep brain stimulation electrode insertion path in Parkinson’s disease. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2024, 60, 6987–7005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, K.R.; Maszczyk, T.; See, A.A.Q.; Dauwels, J.; King, N.K.K. A review on microelectrode recording selection of features for machine learning in deep brain stimulation surgery for Parkinson’s disease. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2019, 130, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inggas, M.A.M.; Coyne, T.; Taira, T.; Karsten, J.A.; Patel, U.; Kataria, S.; Putra, A.W.; Setiawan, J.; Tanuwijaya, A.W.; Wong, E.; et al. Machine learning for the localization of Subthalamic Nucleus during deep brain stimulation surgery: A systematic review and Meta-analysis. Neurosurg. Rev. 2024, 47, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelli, S.; Levi, V.; Vecchio, J.D.V.D.; Mailland, E.; Rinaldo, S.; Eleopra, R.; Bianchi, A. Characterization of Microelectrode Recordings for the Subthalamic Nucleus identification in Parkinson’s disease. In Proceedings of the 2020 42nd Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC), Montreal, QC, Canada, 20–24 July 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 3485–3488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelli, S.; Levi, V.; Vecchio, J.D.V.D.; Mailland, E.; Rinaldo, S.; Eleopra, R.; Bianchi, A.M. An intra-operative feature-based classification of microelectrode recordings to support the subthalamic nucleus functional identification during deep brain stimulation surgery. J. Neural Eng. 2021, 18, 016003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosny, M.; Zhu, M.; Gao, W.; Fu, Y. A novel deep LSTM network for artifacts detection in microelectrode recordings. Biocybern. Biomed. Eng. 2020, 40, 1052–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maged, A.; Zhu, M.; Gao, W.; Hosny, M. Lightweight deep learning model for automated STN localization using MER in Parkinson’s disease. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2024, 96, 106640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, T.; Jannin, P.; Baxter, J.S.H. Generalisation capabilities of machine-learning algorithms for the detection of the subthalamic nucleus in micro-electrode recordings. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 2024, 19, 2445–2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorlini, C.; Forzanini, F.; Coelli, S.; Rinaldo, S.; Eleopra, R.; Bianchi, A.M.; Levi, V. Impact of Microelectrode Recording Artefacts on Subthalamic Nucleus Functional Identification via Features-Based Machine Learning Classifiers. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Metrology for eXtended Reality, Artificial Intelligence and Neural Engineering (MetroXRAINE), St Albans, UK, 21–23 October 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakštein, E.; Sieger, T.; Wild, J.; Novák, D.; Schneider, J.; Vostatek, P.; Urgošík, D.; Jech, R. Methods for automatic detection of artifacts in microelectrode recordings. J. Neurosci. Methods 2017, 290, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboy, M.; Falkenberg, J.H. An Automatic Algorithm for Stationary Segmentation of Extracellular Microelectrode Recordings. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 2006, 44, 511–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagnan, H.; Dolan, K.; He, X.; Contarino, M.F.; Schuurman, R.; Munckhof, P.v.D.; Wadman, W.J.; Bour, L.; Martens, H.C.F. Automatic subthalamic nucleus detection from microelectrode recordings based on noise level and neuronal activity. J. Neural Eng. 2011, 8, 046006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolan, K.; Martens, H.C.F.; Schuurman, P.R.; Bour, L.J. Automatic noise-level detection for extra-cellular micro-electrode recordings. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 2009, 47, 791–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellino, G.M.; Schiaffino, L.; Battisti, M.; Guerrero, J.; Rosado-Muñoz, A. Optimization of the KNN supervised classification algorithm as a support tool for the implantation of deep brain stimulators in patients with Parkinson’s Disease. Entropy 2019, 21, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benouis, M.; Rosado-Muñoz, A. Using Ensemble of Hand-Feature Engineering and Machine Learning Classifiers for Refining the Subthalamic Nucleus Location from Micro-Electrode Recordings in Parkinson’s Disease. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 5157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Li, J.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, H. Automatic feature group combination selection method based on GA for the functional regions clustering in DBS. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2020, 183, 105091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, A.; Bar-Gad, I. Revealing neuronal functional organization through the relation between multi-scale oscillatory extracellular signals. J. Neurosci. Methods 2010, 186, 116–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smiti, A. A critical overview of outlier detection methods. Comput. Sci. Rev. 2020, 38, 100306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breunig, M.M.; Kriegel, H.-P.; Ng, R.T.; Sander, J. LOF. In Proceedings of the 2000 ACM SIGMOD International Conference on Management of Data, New York, NY, USA, 15–18 May 2000; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.; Baltuch, G.H.; Jaggi, J.L.; Danish, S.F. Functional localization and visualization of the subthalamic nucleus from microelectrode recordings acquired during DBS surgery with unsupervised machine learning. J. Neural Eng. 2009, 6, 026006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedregosa, F.F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V.; et al. Scikit-Learn: Machine Learning in Python. 2011. Online. Available online: http://scikit-learn.sourceforge.net (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Guyon, I.; Weston, J.; Barnhill, S.; Vapnik, V. Gene Selection for Cancer Classification using Support Vector Machines. Mach Learn 2002, 46, 389–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponce-Bobadilla, A.V.; Schmitt, V.; Maier, C.S.; Mensing, S.; Stodtmann, S. Practical guide to SHAP analysis: Explaining supervised machine learning model predictions in drug development. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2024, 17, e70056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapley, L. 7. A Value for n-Person Games. Contributions to the Theory of Games II (1953) 307-317. In Classics in Game Theory; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1997; pp. 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.C.-C.; Boulay, C.; Chan, A.D.C.; Sachs, A.J. A Systematic Review of Neurophysiology-Based Localization Techniques Used in Deep Brain Stimulation Surgery of the Subthalamic Nucleus. Neuromodul. Technol. Neural Interface 2024, 27, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga, I.; Bakstein, E.; Gilmore, G.; May, J.; Novak, D. Statistical segmentation model for accurate electrode positioning in Parkinson’s deep brain stimulation based on clinical low-resolution image data and electrophysiology. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0298320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajpurohit, V.; Danish, S.F.; Hargreaves, E.L.; Wong, S. Optimizing computational feature sets for subthalamic nucleus localization in DBS surgery with feature selection. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2015, 126, 975–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khosravi, M.; Atashzar, S.F.; Gilmore, G.; Jog, M.S.; Patel, R.V. Intraoperative Localization of STN during DBS Surgery Using a Data-Driven Model. IEEE J. Transl. Eng. Health Med. 2020, 8, 2500309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Outlier Treatment | DATASET | RAW | EXP | COV | BCK |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NONE | Total | 1228 | 1115 | 1217 | 1207 |

| NOT STN | 804 | 726 | 794 | 793 | |

| STN | 424 | 389 | 423 | 414 | |

| ORH | Total | 981 | 893 | 1028 | 1044 |

| NOT STN | 633 | 582 | 693 | 699 | |

| STN | 348 | 311 | 335 | 345 | |

| ORM | Total | 1094 | 992 | 1085 | 1076 |

| NOT STN | 757 | 697 | 775 | 769 | |

| STN | 337 | 295 | 310 | 307 |

| EN | RF | SVC | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACC | F1-Score | ACC | F1-Score | ACC | F1-Score | |

| RAW | 0.912 (0.025) | 0.876 (0.032) | 0.932 (0.013) | 0.899 (0.019) | 0.931 (0.021) | 0.902 (0.028) |

| EXP | 0.916 (0.016) | 0.881 (0.023) | 0.936 (0.015) | 0.906 (0.022) | 0.931 (0.02) | 0.902 (0.028) |

| COV | 0.929 (0.009) | 0.899 (0.013) | 0.938 (0.015) | 0.909 (0.022) | 0.93 (0.011) | 0.902 (0.015) |

| BCK | 0.926 (0.013) | 0.893 (0.016) | 0.934 (0.017) | 0.903 (0.025) | 0.932 (0.016) | 0.904 (0.021) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Levi, V.; Coelli, S.; Gorlini, C.; Forzanini, F.; Rinaldo, S.; Golfrè Andreasi, N.; Romito, L.; Eleopra, R.; Bianchi, A.M. The Role of MER Processing Pipelines for STN Functional Identification During DBS Surgery: A Feature-Based Machine Learning Approach. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 1300. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering12121300

Levi V, Coelli S, Gorlini C, Forzanini F, Rinaldo S, Golfrè Andreasi N, Romito L, Eleopra R, Bianchi AM. The Role of MER Processing Pipelines for STN Functional Identification During DBS Surgery: A Feature-Based Machine Learning Approach. Bioengineering. 2025; 12(12):1300. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering12121300

Chicago/Turabian StyleLevi, Vincenzo, Stefania Coelli, Chiara Gorlini, Federica Forzanini, Sara Rinaldo, Nico Golfrè Andreasi, Luigi Romito, Roberto Eleopra, and Anna Maria Bianchi. 2025. "The Role of MER Processing Pipelines for STN Functional Identification During DBS Surgery: A Feature-Based Machine Learning Approach" Bioengineering 12, no. 12: 1300. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering12121300

APA StyleLevi, V., Coelli, S., Gorlini, C., Forzanini, F., Rinaldo, S., Golfrè Andreasi, N., Romito, L., Eleopra, R., & Bianchi, A. M. (2025). The Role of MER Processing Pipelines for STN Functional Identification During DBS Surgery: A Feature-Based Machine Learning Approach. Bioengineering, 12(12), 1300. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering12121300