Abstract

Early flood forecasting systems can mitigate flood damage during extreme events. Typically, the effects of flood events in terms of inundation depths and extents are computed using detailed hydraulic models. However, a major drawback of these models is the computational time, which is generally in the order of hours to days for large river basins. Gaining insight in the outflow hydrographs in case of dike breaches is especially important to estimate inundation extents. In this study, NARX neural networks that were capable of predicting outflow hydrographs of multiple dike breaches accurately were developed. The timing of the dike failures and the cumulative outflow volumes were accurately predicted. These findings show that neural networks—specifically, NARX networks that are capable of predicting flood time series—have the potential to be used within a flood early warning system in the future.

1. Introduction

Inundation of the hinterland due to dike breaches poses a worldwide flood risk. It is expected that flood losses will significantly increase in the future due to climate change and as societies become wealthier [1]. Accurate prediction of potential dike breach locations, as well as the timing of a dike failure and resulting outflow hydrograph, are crucial for decision-makers to establish appropriate flood mitigation measures such as evacuation plans. Up until now, two-dimensional (2D) hydraulic models are generally used to predict the disastrous consequences of river flood events (e.g., [2,3,4]). However, the computational times of these models are relatively long, especially when large river basins are considered. Furthermore, many hydraulic simulations are required according to a probabilistic approach to find the potential dike breach locations since the critical water level at which a dike may fail is highly uncertain and varies spatially along a river reach. In crisis situations, a quick estimate of the dikes most prone to breach is essential. Therefore, 2D hydraulic models cannot be used for real-time flood forecasting purposes, even with a computational cluster.

For this reason, neural networks are applied more frequently in the field of hydrology in recent times [5]. Neural networks are data-driven models trained based on the input–output relations of a physically-based model or field measurements. A neural network has as advantage that it is fast with simulation times of less than a second, that it can handle incomplete and noisy input data, and that it is able to reproduce complex nonlinear behavior between input and output [6,7,8]. Most of the studies that developed neural networks for flood forecasting purposes focused on the prediction of discharges and/or water levels at specific sites based on data of upstream gauge stations without considering the effects of dike failure (e.g., [9,10,11,12,13]). Shen and Chang [8] extended the use of neural networks by developing NARX neural networks that were capable of predicting flood time series in terms of inundation extents in urban areas. These inundations were caused by extreme precipitation events. It was found that a NARX neural network can effectively be used for multistep-ahead forecasts even when imperfect input data is used for rainfaill triggered flood events [8]. Bomers et al. [14] showed the applicability of neural networks in case of dike breaches by predicting maximum water levels during an extreme historic flood event. However, the study made use of predefined dike breach locations while these locations are highly uncertain in reality. Furthermore, breach outflow peaks and hydrographs have already been successfully predicted using neural network approaches (e.g., [15,16]). These studies focused on a single breach only and prediction of the dike breach location along a river stretch was not included in the analysis.

Even though the previous studies successfully showed the possibilities of neural networks to be used in a flood forecasting system in the future, no models exist that can predict both fast and accurately the dike breach location, timing, and outflow volume in case of extreme flood events. This study shows the potential of using neural networks to predict if a dike section will fail during a flood event, the timing a dike will fail, and the corresponding outflow hydrographs, since these parameters are the main drivers of the total flood damage during a flood event. Multiple dike breach locations in a river delta with multiple river bifurcations are considered. The developed neural networks should be able to correctly predict outflow hydrographs of the dike breaches based on an upstream discharge wave. To do so, the effects of a dike breach on downstream water level reductions and, consequently, dike failure probabilities of the remaining potential dike breach locations should be accurately captured by the neural networks.

To reach the objective of this study, several simplifying hypotheses are made. First, a deterministic approach is applied in which dike sections only fail due to overtopping failure mechanism, independent of the type of structure. Consequently, based on the hydraulic modeling simulation, the potential dike breach locations are known. Neural networks are only developed for the dike sections that breached during at least one of the multiple flood events simulated with the hydraulic model to generate the training data. The trained neural networks predict if these dike sections will fail and predict the resulting outflow hydrographs.

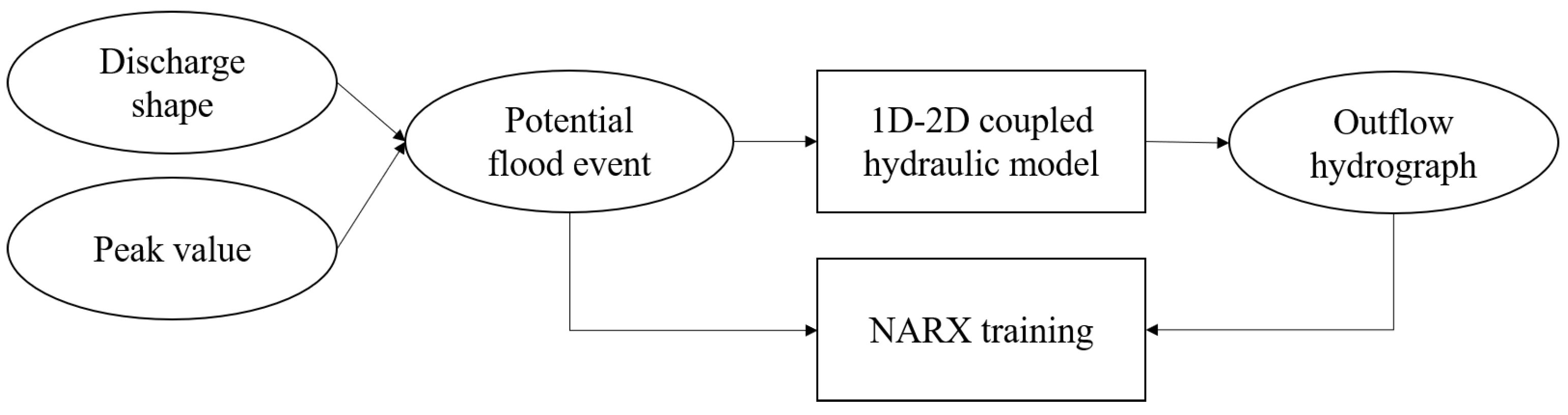

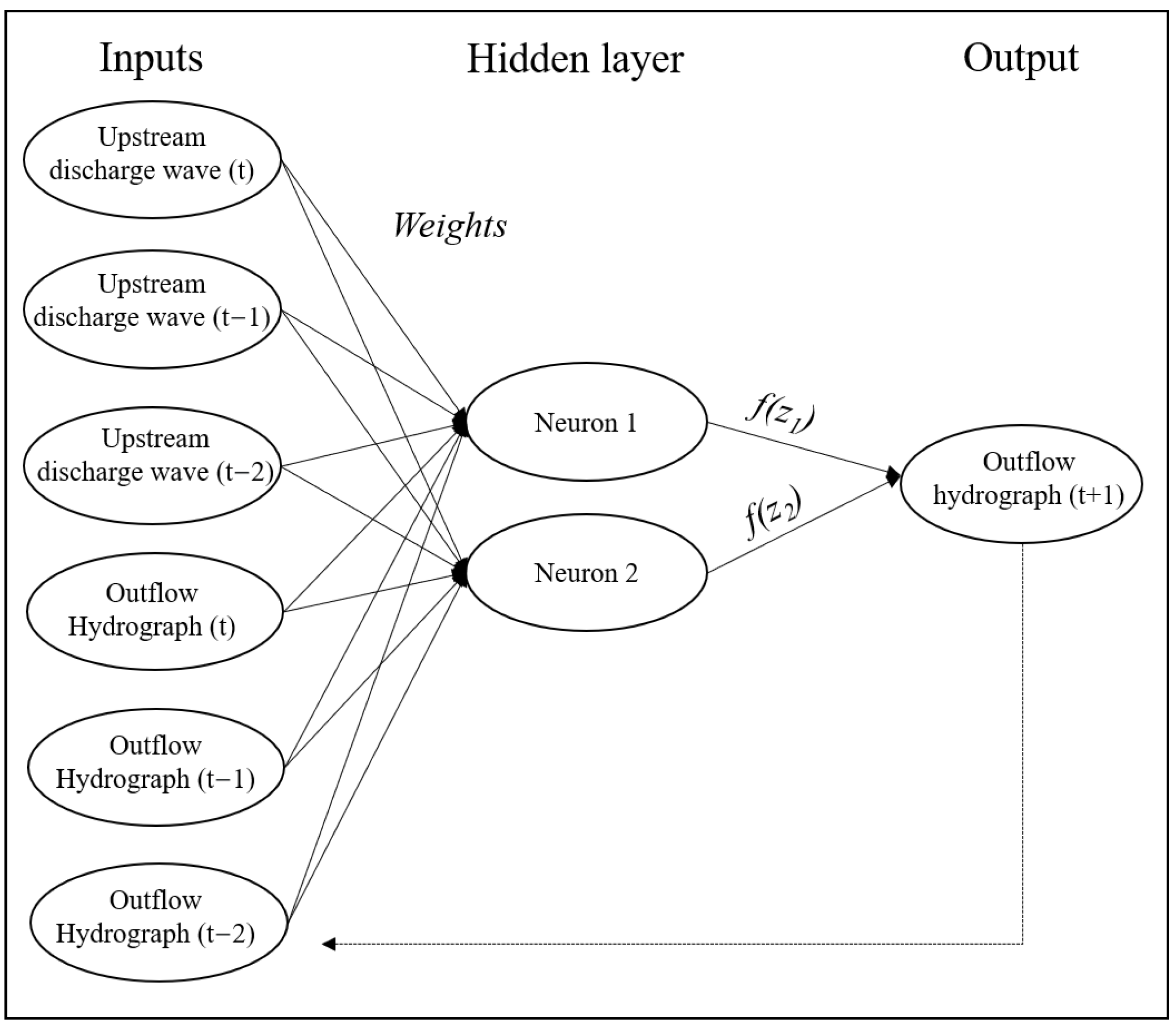

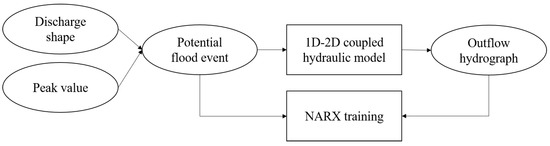

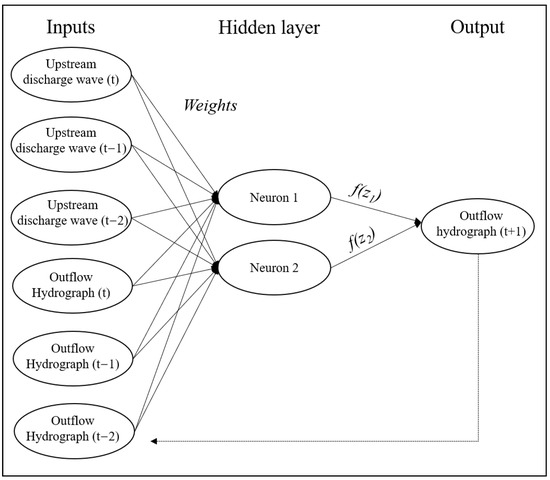

If the outflow hydrographs of multiple dike breaches during potential flood events can be predicted both fast and accurately, this study shows the applicability of neural networks to be used in real-time flood forecasting systems in the near future. The Dutch Rhine river delta is used as a case study (Section 2). However, the proposed methodology can be applied to any river system in the world where flood defenses may fail, resulting in outflow hydrographs. First, training data is generated using a one-dimensional–two-dimensional (1D–2D) coupled hydraulic model in which the river is solved in 1D and the hinterland in 2D. The hydraulic model setup is described in Section 3.1. The upstream peak discharge and shape of the discharge wave is varied to ensure that a wide range of potential realistic flood events are simulated (Section 3.3). These upstream discharge waves result in dike breaches and, consequently, outflow hydrographs in the studied area. These input–output relations of the hydraulic model are used to train the neural networks (Figure 1), presented in Section 4. The results are shown in Section 5. The paper ends with a discussion and conclusions in Section 6 and Section 7, respectively.

Figure 1.

The proposed methodology to train the artificial neural networks that are capable of predicting outflow hydrographs of potential dike breaches.

2. Study Area

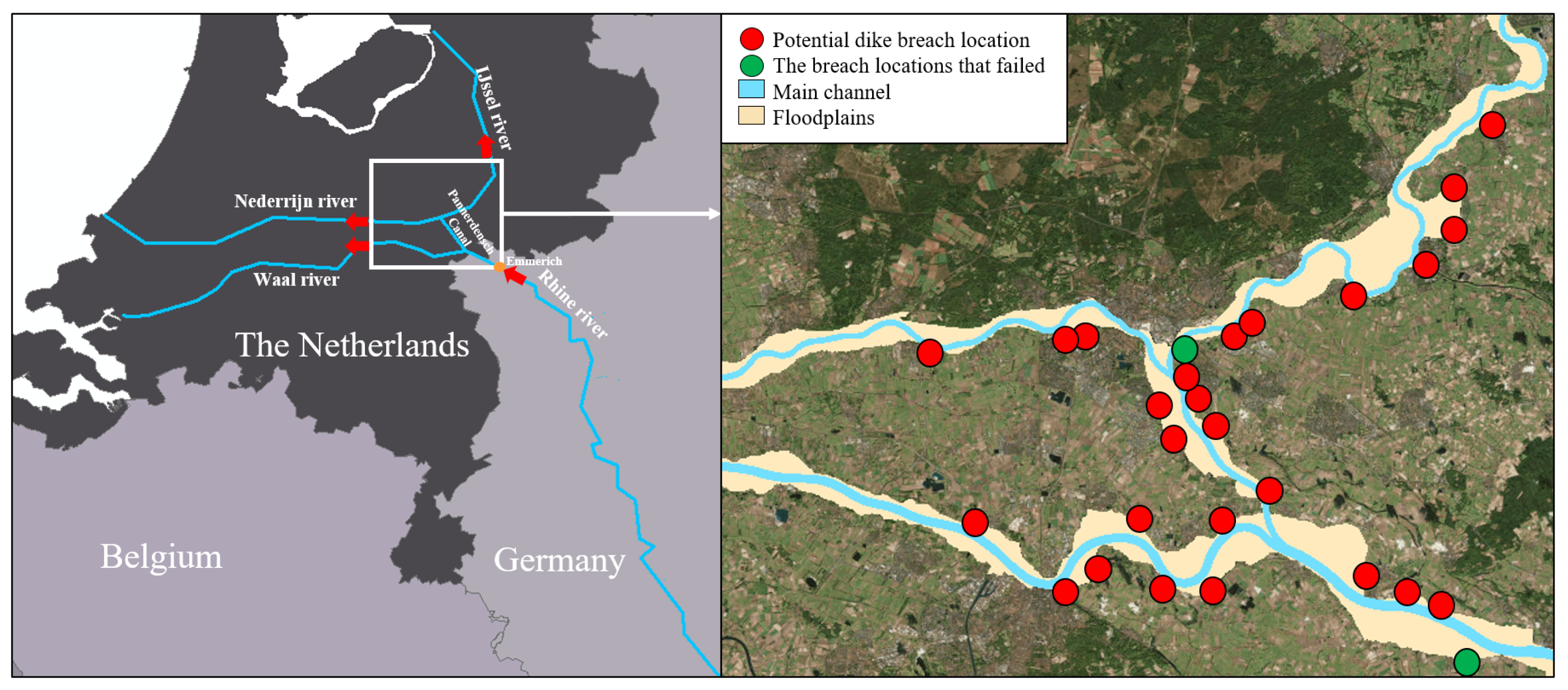

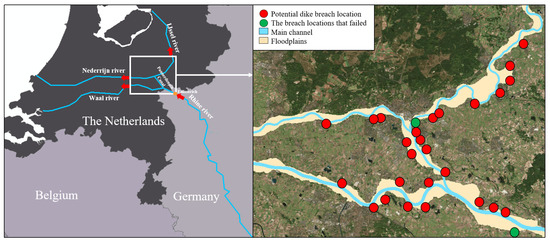

The Rhine river originates in the Alps of Switzerland and flows through Germany, where the flood-prone area increases until it becomes a river delta in the Netherlands [17]. The Rhine river enters the Netherlands at Lobith, where it bifurcates into the Waal river and Pannderdensch Canal (Figure 2). Subsequently, the Pannerdensch Canal bifurcates into the Nederrijn and IJssel rivers.

Figure 2.

(Left) The Dutch Rhine river delta used as a case study. The red arrows indicate the flow direction; the orange dot indicates the location of the upstream model boundary (Emmerich, Germany). The Rhine river enters the Netherlands at the German–Dutch border. (Right) The potential dike breach locations included in the analysis. The red dots represent all potential dike breach locations considered in the hydraulic simulations, whereas the green dots represent the dike breach locations that failed during one or more of the hydraulic simulations.

In this study, we focus on the the discharge-dominated part of the Rhine river delta in the Netherlands. The downstream river sections influenced by the tide of the North Sea are not included to reduce model complexity. In the considered area, floods mainly evolve during the winter months due to heavy precipitation events in combination with frozen or saturated soils in the upstream parts of the river basin. Currently, the Dutch water policy assumes a fixed discharge partitioning along the Dutch Rhine river branches during such extreme events. Of the total discharge at Lobith, it is assumed that approximately 65% flows to the Waal river, 19% to the Nederrijn river, and around 16% to the IJssel river [18]. These river branches are protected by dikes in order to protect the hinterland from being flooded. These dikes may fail under extreme conditions influencing this predefined discharge partitioning due to a reduction in the local water levels and backwater effects [2]. The hydraulic model used to generate the training data used to train the neural networks has to be able to include this dynamic behavior during flood events (Section 3).

3. Hydraulic Model

3.1. Model Setup

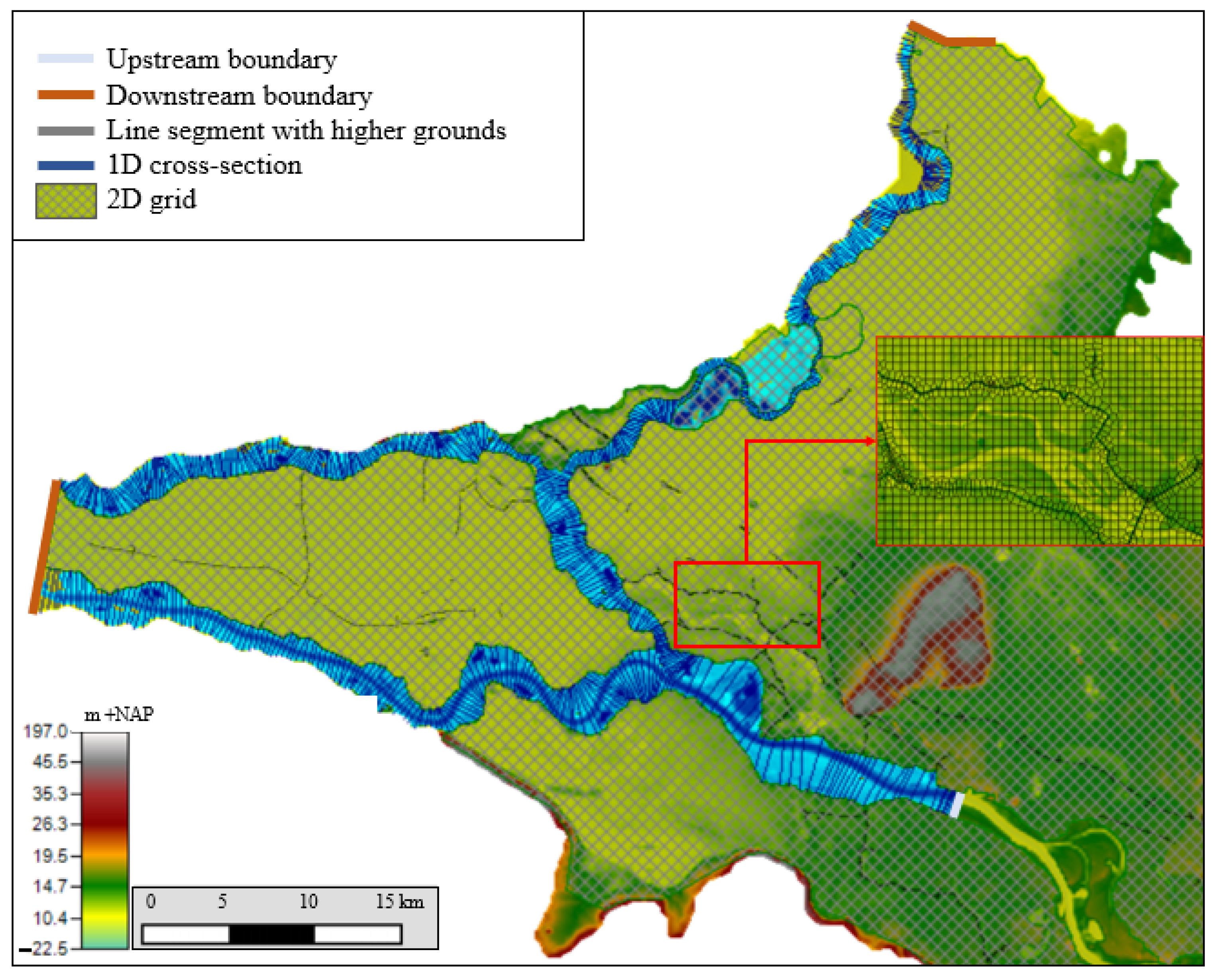

The one-dimensional–two-dimensional (1D-2D) coupled hydraulic model of Bomers et al. [2] is used in this study. The model domain of this calibrated and validated model is decreased to reduce computational times. In this study, the upstream boundary is located at Emmerich, Germany, and the model domain stretches to the Dutch Deltaic area (Figure 2). The model bathymetry, roughness classifications, and the locations and heights of the dikes represent the present situation. These data were provided by the Dutch Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management and the Landesamt für Natur, Umwelt und Verbraucherschutz (LANUV) of Northrhine-Westfalia.

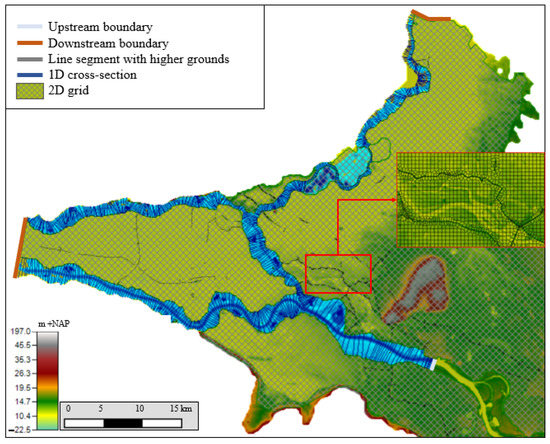

At Emmerich, a discharge wave is used as an upstream boundary condition, whereas normal depths are used as downstream boundary conditions [19]. HEC-RAS (v. 5.0.3), developed by the Hydrologic Engineering Center (HEC) of the US Army Corps of Engineers, is used to perform the hydraulic simulations using the diffusive wave equations. In this model, the main channel and floodplains are discretized by 1D profiles. During extreme flood events, the flow typically has a dominant flow direction in these regions, making the use of 1D profiles suitable as it reduces computational times compared to a fully 2D model. The hinterland is discretized on a 2D grid to accurately capture the inundation patterns and extents caused by the potential dike breaches (Figure 3). The 2D grid has a resolution of approximately 150 × 150 m. This 2D grid is aligned with higher grounds such that overland flow patterns are accurately captured by the model. Furthermore, the 2D grid extends upstream of the 1D main channel and floodplain boundary to ensure that the storage capacity of the hinterland is correctly captured (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The 1D-2D coupled hydraulic model setup.

The 1D profiles and 2D grids are connected by a structure representing the dike sections along the various river reaches. In this study, we assume that dikes will only fail by the overtopping failure mechanism, which is the most common failure mechanism of modern dikes [20]. It is assumed that the various potential dike breach locations will fail if the simulated water level is equal to the dike crest level. Consequently, no detailed information about the age and construction techniques of the dikes, determining the failure probabilities, are required. In total, 28 potential dike breach locations are considered (Figure 2). These locations are selected based on their expected consequences in case of a dike failure [21]. As a result, a dike breach in a specific dike section leads to similar overland flow patterns independent of the exact dike breach location in that specific dike section. Furthermore, the various dike sections are modeled as infinitely high dikes, meaning that water will only leave the river system through the dike breaches. Additional overflow along surrounding dike sections is not included in the model setup to reduce complexity of the system.

Dike breach growth is highly uncertain. Many models exist that try to simulate this uncertain process by predicting breach dimensions over time. However, overland flows and inundation extents are not sensitive to the breach growth model used [22]. Even though the use of different breach growth models, predicting different breach dimensions over time, resulted in different outflow hydrographs, the total outflow volumes were found to be predicted more or less the same by the different breach growth models. Correct prediction of the total outflow volume is important since this determines the inundated areas to a large extent. Therefore, in this study, we use a simple approach and assume that dikes immediately breach to the level of the natural terrain when the simulated water level is equal to the critical water level. Furthermore, a constant breach width of 150 m is implemented.

3.2. Calibration and Validation of the Hydraulic Model

The hydraulic model was calibrated and validated by Bomers et al. [2]. Calibration was performed such that simulated maximum water levels were close to measurements by changing the main channel roughness. During the calibration procedure, a maximum deviation in simulated water levels of 10 cm was assumed. The 1995 Rhine river flood event was used for calibration, resulting in a maximum discharge of around 12,060 m3/s at Lobith, the German-Dutch border. This event corresponds with a return period of approximately 60 years [23]. Calibration was performed based on 14 measurement stations present in the model domain. After calibration, the maximum water levels were predicted with an average deviation of 1 cm compared to measurements.

The 1993 discharge wave with a maximum discharge of around 11,100 m3/s at Lobith, having a return period of approximately 30 years [23], was used for model validation. At the 14 measurement stations, a deviation of less than 7 cm in simulated maximum water levels compared to measurements was found. Furthermore, the discharge partitioning along the Dutch Rhine river branches was predicted with high accuracy, only deviating 3.7% from measurements on average. For more details about the calibration and validation procedure of the hydraulic model, we refer to Bomers et al. [2].

The calibration and validation results give confidence in the accuracy of the hydraulic model to be used for large future flood events. However, both the 1993 and 1995 flood events did not result in any dike breaches. Furthermore, no overtopping occurred. As a result, only the instream flow conditions could be validated. The last time dike breaches occurred in the Dutch Rhine river system was in 1926. However, many river interventions have been executed (e.g., dike reinforcement projects, widening of river floodplains), making this flood event unsuitable for calibration purposes.

3.3. Training Data: Upstream Discharge Waves

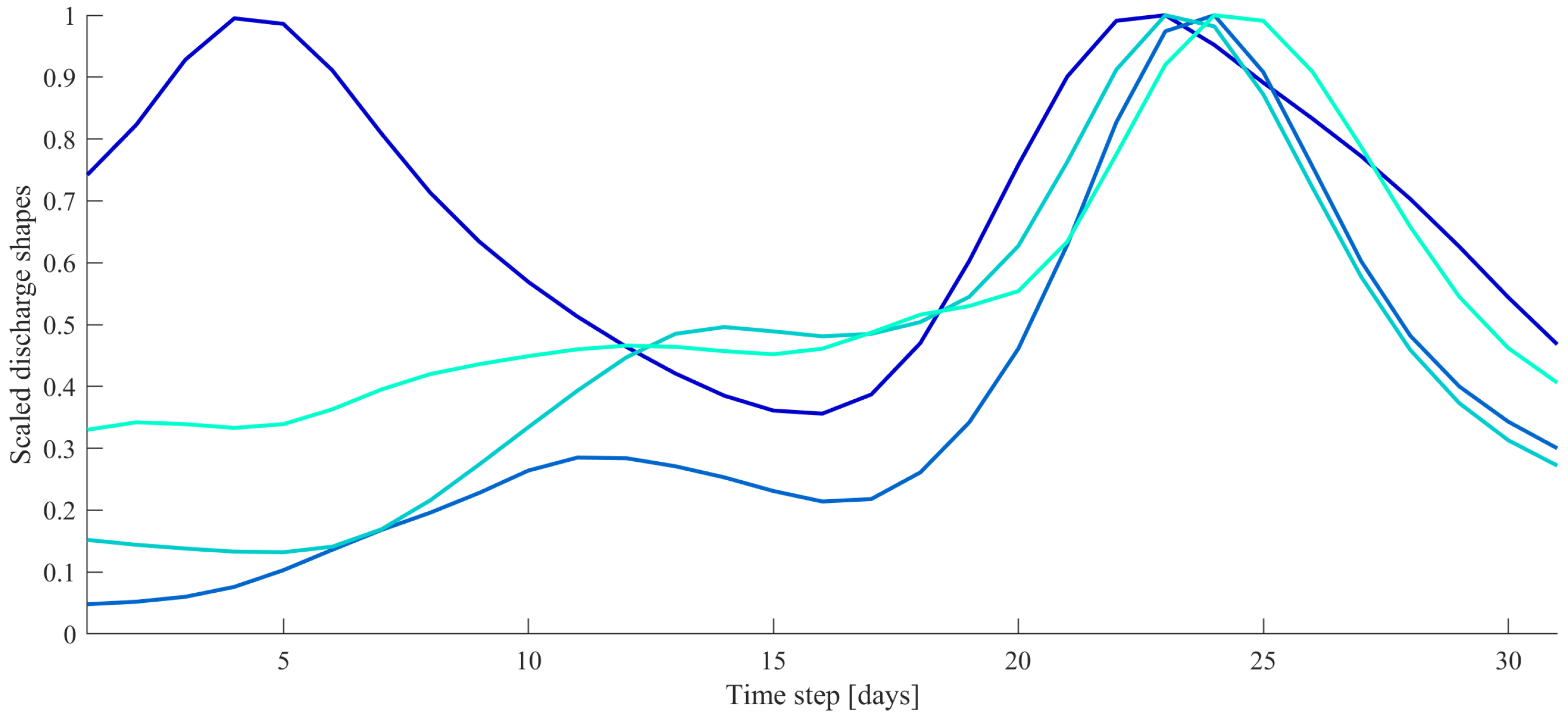

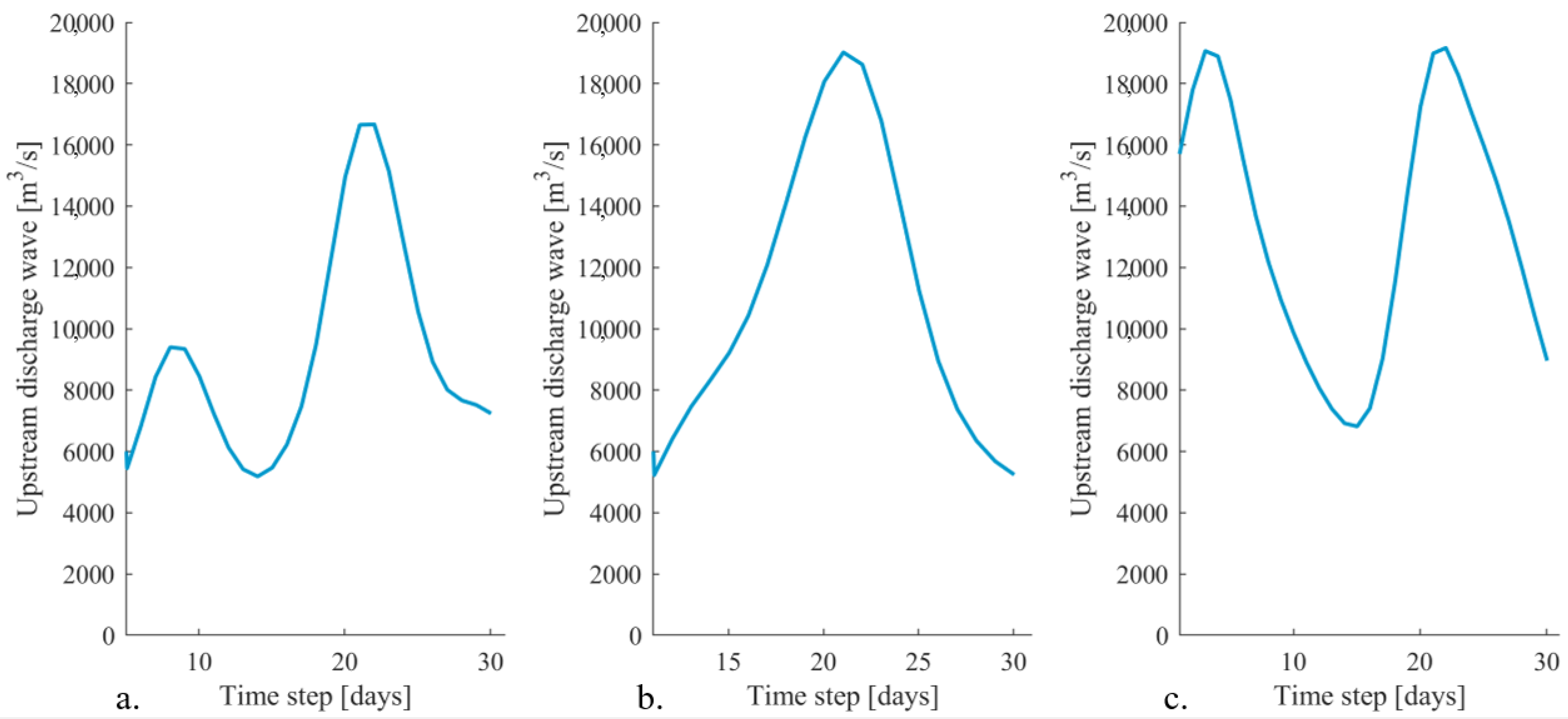

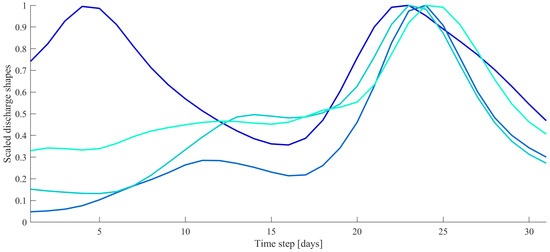

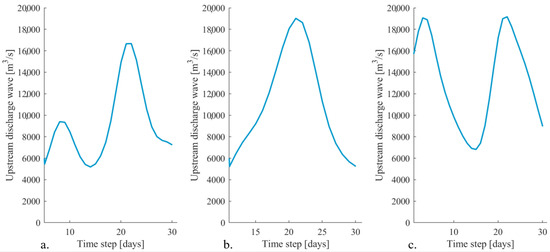

This study aims to develop neural networks that are capable of predicting dike breach failures and corresponding outflow hydrographs during extreme events. To ensure that sufficient realistic flood events are used to train the neural networks, 80 model runs are performed with varying upstream discharge shapes and peak values. In total, 80 different discharge shapes are considered that may occur under current climate conditions. These discharge shapes are based on GRADE (Generator of rainfall and discharge extremes), which has a data set consisting of 50,000 years of discharges based on resampled measured weather conditions such as precipitation and temperature [24]. Of this data set, flood events having a peak value larger than 12,000 m3/s were selected. A 30-day time window was used to generate various potential flood events. Using this data set compared to measured discharges has as an advantage the fact that a much larger variety of potential discharge shapes can be included in the training data set (e.g., a flood event with a sharp peak, broad peak, or two peaks) (Figure 4). The measured data set only goes back to 1901 and only the largest flood event that occurred in 1926 had a discharge larger than 12,000 m3/s [25].

Figure 4.

Different normalized discharge waves that are used to get realistic potential flood events by multiplying these discharge wave shapes with the sampled peak values.

For the Dutch Rhine river branches, a maximum design discharge is considered corresponding to a return period of 100,000 years. This corresponds to a peak value of between 16,500 and 19,300 m3/s at the German–Dutch border [26]. This range is used to scale the 80 different discharge shapes in terms of its peak value (Figure 4). A Latin hypercube sampling method is used to ensure that this range is sufficiently captured by the limited model runs [27]. The discharge range (16,500–19,300 m3/s) is divided into eight subintervals, each having an equal probability of occurrence. As a result, 10 peak values are randomly sampled in each subinterval, resulting in 80 potential flood events.

4. The NARX Setups

Even though many data-driven models exist, we focus on the development of neural networks. Neural networks are the most commonly used response surface surrogate models in water resources problems [5] since they provide an attractive solution to problems in complex systems because they can, theoretically, handle incomplete and noisy data [6]. Furthermore, neural networks have shown to be highly accurate in predicting water levels during flood events (e.g., [7,28,29,30,31]) as well as in predicting breach outflow hydrographs at a single location (e.g., [15,16]).

This study focuses on the prediction of the outflow hydrographs of potential dike breaches requiring the need of neural networks that are capable of predicting a time-varying output based on an input time series. For this reason, nonlinear autoregressive with external input (NARX) neural networks are developed for each dike section that breached during at least one of the hydraulic simulations performed to create the training data. A NARX is a recurrent dynamic neural network with feedback connections suitable for time series prediction [8,32]. NARX networks have widely been applied in the field of hydrology ranging from predicting groundwater levels [32] to floods within urban drainage systems [33] and rainfall-triggered flood forecasting in urban and rural areas [8,34]. This study uses NARX neural networks to predict outflow hydrographs of multiple potential dike breach locations for the first time. A hydraulic model with computational times in the order of 10 h for a single simulation is used to create the training data, limiting the data set that can be created and consequently used to train the NARX networks. A NARX predicts a time series y(t) based on d past values of y(t) and an input time series x(t) according to the following equation:

In this study, y(t) represents the predicted dike breach outflow hydrograph, x(t) the upstream discharge wave, and d the number of past time steps. The upstream discharge waves and the outflow hydrographs, both having a time step of one hour, are normalized since it has been proved that the accuracy of NARX predictions increases if trained on normalized data sets since neural networks tend to favor inputs that can have larger values [6]. The data sets are normalized to a [−1,1] interval [33].

A NARX network is set up for each dike breach location that failed during the hydraulic modeling simulations. It was decided to set a NARX network up for each dike breach location separately instead of a single network for the entire system to reduce the complexity of the neural network structure and the training time required. Furthermore, this approach is justified by the fact that the NARX network should be able to predict the spatial relations already present in the hydraulic model used to create the training data. A dike breach leads to a reduction in downstream water levels. Consequently, dike failure probabilities in downstream branches decreases. The question of whether the trained neural networks are capable of reproducing this highly nonlinear system behavior is addressed in Section 5.3.

The NARX networks are developed using the MATLAB Deep Learning Toolbox 14.1. A feed-forward network is developed, meaning that the information in the neurons flows in one direction: from an input layer through a hidden layer with a number of neurons to an output layer [6,29]. The hyperbolic tangent sigmoid activation function is used to compute an output based on the weighted sum of all inputs. A sigmoid activation function is generally applied in the literature since it is capable of introducing nonlinear behavior to the network [30,35].

During the training procedure, the number of neurons present in the hidden layer and the delays d must be specified by the modeler. Both parameters are case-specific since they depend on the complexity of the system [36] as well as on the training data availability [5]. Most commonly, a trial-and-error procedure is applied to determine the appropriate number of neurons and delays [8,28,37]. The same approach is applied in this study. It was found that the NARX networks produce the most reliable results for two neurons in the hidden layer and two time step delays (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Setup of the trained NARX networks with the upstream discharge wave and predicted outflow hydrographs as input, considering two time delays, and two neurons in the hidden layer.

A general problem with response surface surrogate models is overfitting [29,31], which means that the surrogate model fits the noise existing in the training data rather than the underlying function [5]. Two well-established approaches exist to avoid overfitting during the training procedure of neural networks: early stopping using the Levenberg–Marquardt (LM) algorithm and Bayesian regularization [5,6]. Both approaches are implemented in the MATLAB Deep Learning Toolbox. The two approaches were tested, and it was found that the LM algorithm resulted in a slightly more accurate NARX setup (i.e., a slightly higher Nash–Sutcliffe coefficient). Furthermore, the LM algorithm is commonly applied to train NARX neural networks (e.g., [32,33,34]), as it is considered as a fast and efficient training function [38]. During the training procedure, the training data set is randomly divided into three sets: training (60%), validation (20%), and testing (20%). The training data set is used to train the NARX network, the validation data set is used to test whether increasing the data set during the training phase results in a more accurate NARX network, and the testing data set represents an independent data set used to validate the NARX network performance after being trained.

The NARX networks are trained according to an open-loop [32], i.e., a single step, form resulting in more efficient training compared to a closed-loop form in which predictions are iterated over many time steps. The maximum number of epochs was set to 1000. The mean squared error (MSE) was used as a loss function such that the error in estimations of the maximum outflow discharge is more heavily weighted than the errors in smaller values. Since training a neural network multiple times will always result in a slighty different network structure as a result of different starting conditions, 10 NARX networks were trained for each breach location. Even though the differences in the overall performance of the various trained networks were small, the NARX networks with the highest accuracy are presented in Section 5. The accuracy of the NARX networks is evaluated using the Nash–Sutcliffe model efficiency coefficient (NSE), which can be computed with the following equation [39]:

where Qm is the outflow discharge predicted by the NARX network (m3/s), Qo is the target outflow discharge simulated by the hydraulic model (m3/s), and is the average of the target outflow discharge (m3/s). N represents the total number of simulations included in the calculation and n the index. A NSE value equal to 1 corresponds with a perfect fit between the NARX network predictions and the hydraulic model output, whereas a value below 0 indicates that the mean outflow discharge simulated by the hydraulic model is a better predictor [40].

5. Results

It was found that only two out of the 28 potential dike breach locations failed due to the 80 flood events considered, namely the most upstream potential dike breach location located just downstream of the upstream boundary condition of the hydraulic model, and the most upstream potential dike breach location along the IJssel river (green dots in Figure 2). These two breach locations are referred to as, respectively, “the most upstream dike breach location” and “the IJssel river dike breach location” from now on. Only for these two locations a NARX network is set up to test whether such a neural network is capable of correctly predicting the shape and total volume of a dike breach outflow hydrograph. First, the hydraulic modeling results are presented in Section 5.1 to gain insights in the system behavior during flood events. This insight is required to identify the main difficulties within the system that should be captured by the NARX networks. The accuracy of the developed NARX networks is described in Section 5.2, Section 5.3 and Section 5.4.

5.1. Hydraulic Modeling Results

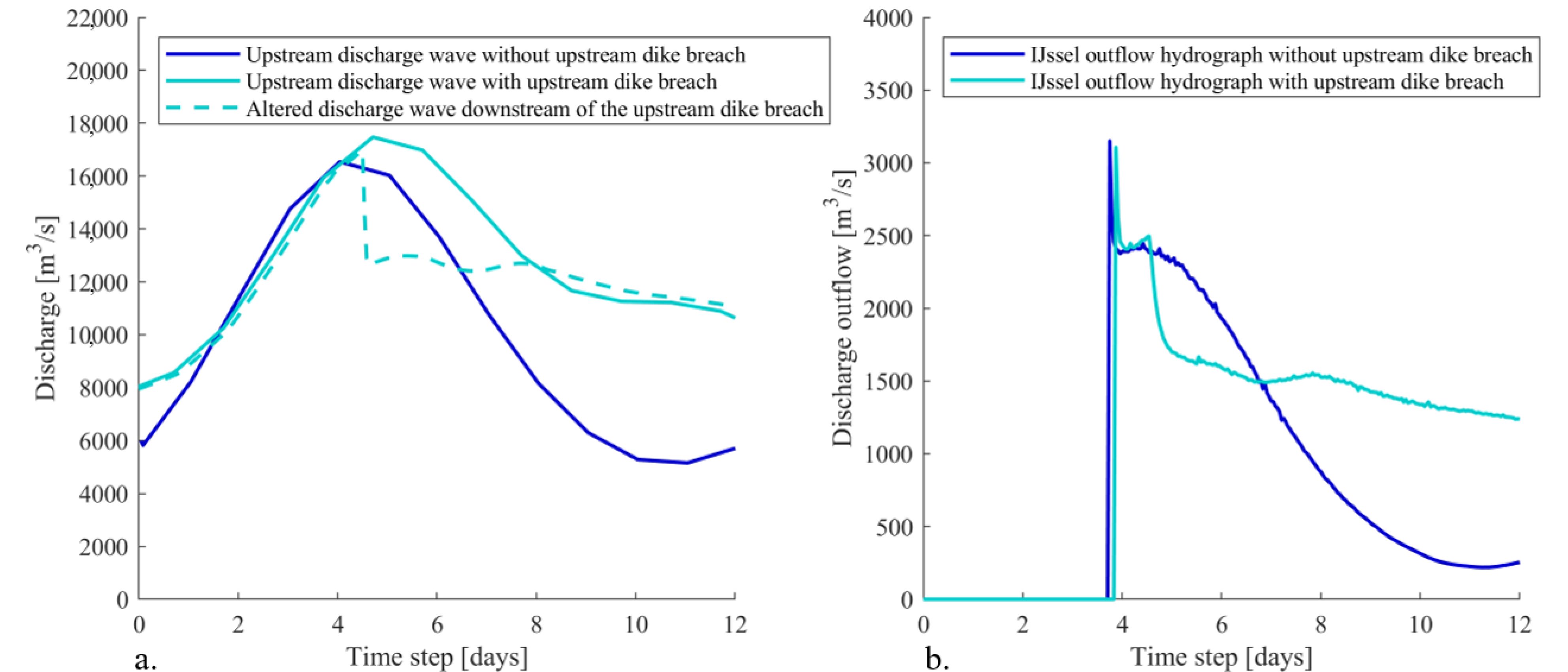

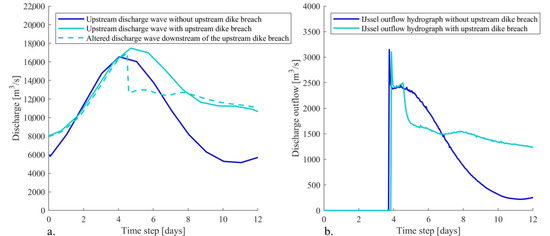

During all simulations, the breach location along the IJssel river (Figure 2) overtopped and thus breached first. The most upstream dike breach location (Figure 2) only failed if the peak of the upstream discharge wave was larger than approximately 17,100 m3/s. The shape of the outflow hydrograph at this location was not influenced by the dike breach along the IJssel river since the distance between the two locations was sufficiently large that backwater effects were vanished. However, the most upstream dike breach does significantly affect the shape of the outflow hydrograph of the dike breach at the IJssel river (Figure 6). This can be explained by the fact that the most upstream dike breach changes the shape of the discharge wave in the river system. The originally smooth discharge wave now has a sudden drop due to the outflow through the breach (Figure 6). This altered discharge shape consequently changes the shape of the outflow hydrograph at the IJssel river.

Figure 6.

(a) The upstream instream discharge waves used as boundary condition of the hydraulic model and as input of the NARX networks (solid lines) and corresponding altered instream discharge wave if a dike breach occurs at the most upstream breach location just downstream of the dike breach (dashed line). (b) Corresponding outflow hydrographs at the IJssel dike breach location (i) if no dike breach occurs at the most upstream dike breach location and (ii) if a dike breach occurs at the most upstream dike breach location. For the locations of the most upstream and IJssel river dike breach locations, please see Figure 2.

The NARX networks at both dike breach locations are set up with the upstream discharge wave as input parameter. Therefore, special attention must be paid to the accuracy of the NARX network of the IJssel breach location for upstream discharges with a peak value lower and higher than 17,100 m3/s resulting in a smooth and highly altered outflow hydrograph, respectively.

5.2. Validation of the NARX Neural Networks

The hydraulic model cannot be used as an early flood forecasting tool because of the long computational time of a single simulation in the order of 10 h on a standard PC. However, the NARX networks were trained in less than 5 s. After training, it was possible to compute the outflow hydrographs of 80 potential flood events in 0.07 s. Even though creating the training data with the hydraulic model is a huge time investment, equal to approximately 800 h in this study, the NARX networks have great potential to be used for flood forecasting purposes when trained.

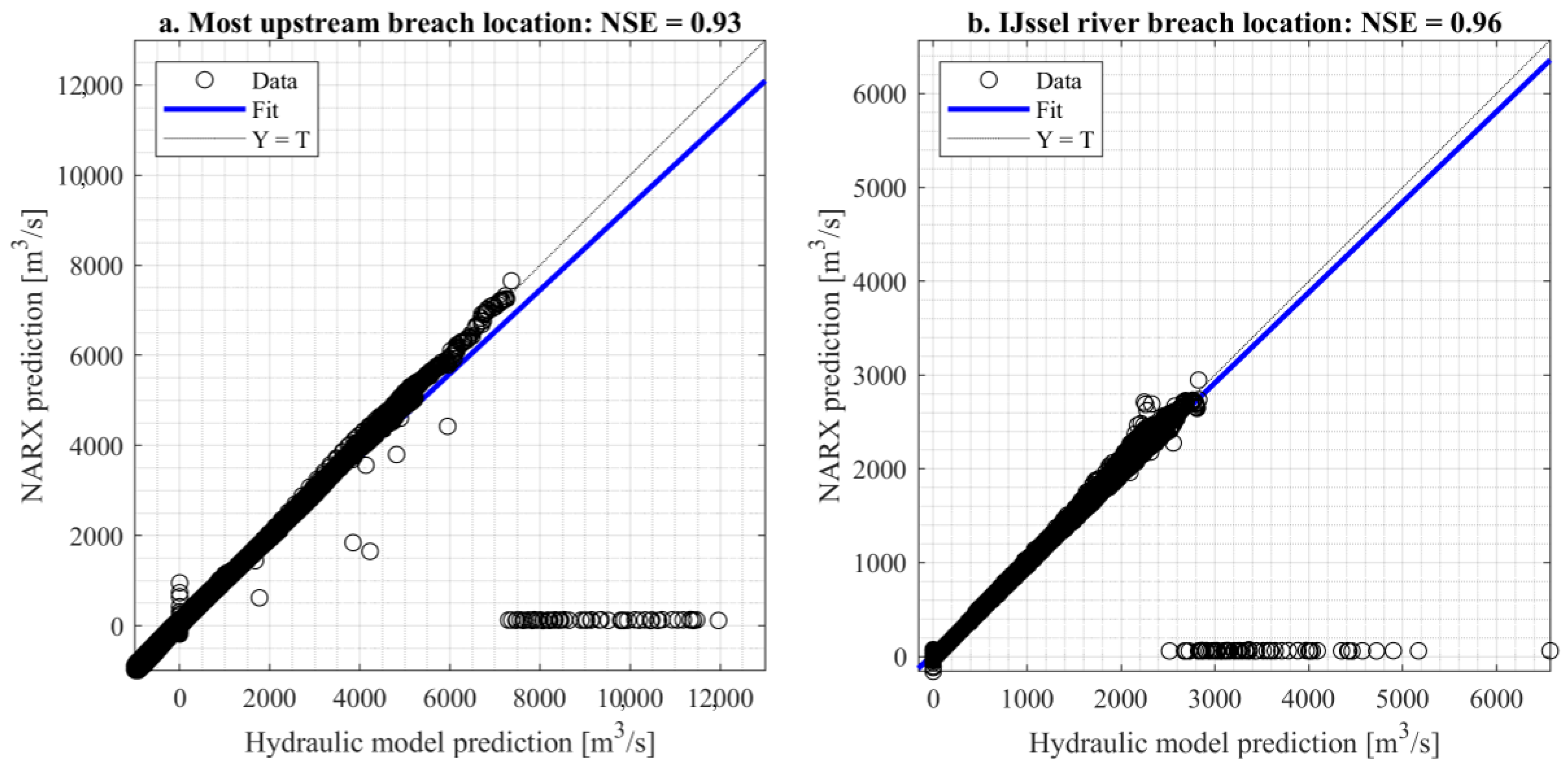

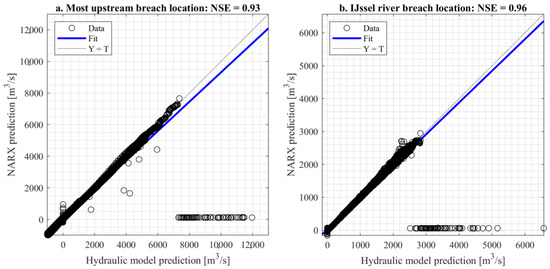

During the training, validation, and testing procedures, different upstream discharge shapes were used. It was found that the NARX networks were able to respond to varying upstream discharge shapes accurately, even for the ones highly deviating from the ones present in the training data set. For the most upstream dike breach location and the dike breach location along the IJssel river, an NSE of 0.93 and 0.96 was found, respectively. Figure 7 shows the regression lines of the two dike breach locations; the predictions of the hydraulic model and the NARX networks are presented for each time step. It shows that the NARX predictions closely resemble the hydraulic model output since almost all data points are present at the linear 1:1 line. However, some differences are present:

Figure 7.

Regression lines for the two potential dike breach locations where the blue line represents the 1:1 linear fit and the Y = T line the fitted linear line based on the training data produced with the hydraulic model (T) and NARX predictions (Y).

- If no dike breach has occurred yet (hydraulic model output is equal to 0), the NARX network predicts a small negative or positive discharge. This can be seen by the vertical data points clustered around T = 0 in Figure 7).

- The NARX networks predict the peak of the outflow hydrograph one time step later compared to the hydraulic model. This explains the horizontal data points clustered around Y = 0 in Figure 7).

- The maximum outflow discharges seem to be underpredicted by the NARX networks, especially for the most upstream breach location. This can be seen by the data points representing with discharges larger than 6000 m3/s deviating from the 1:1 line (Figure 7a).

These three findings are discussed in more detail in the next section, in which we will focus on the shapes of the predicted outflow hydrographs. The implications of these deviations on the total outflow volume, important for flood extent predictions, are discussed in Section 5.4. To do so, the results of three upstream discharge waves are presented: one with a peak value lower than 17,100 m3/s such that the upstream dike breach location does not breach and two discharge waves with a peak value larger than 17,100 m3/s, both with a different discharge wave shape (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

(a–c) The three upstream discharge waves used to verify the suitability of the NARX networks to predict outflow hydrographs of potential dike breaches.

5.3. Prediction of the Outflow Hydrograph Shapes

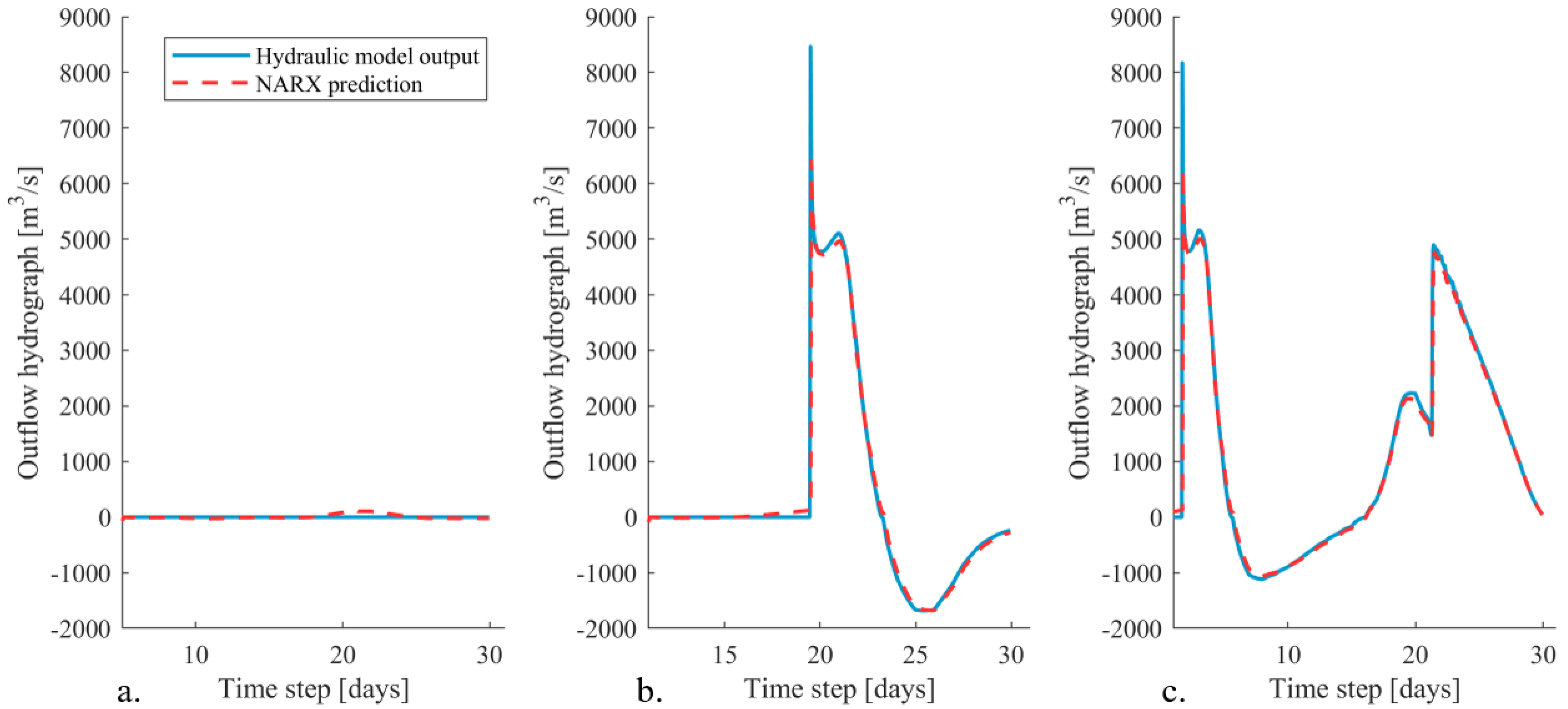

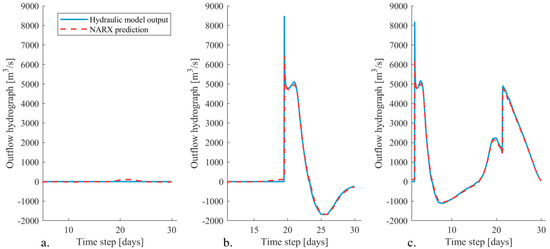

5.3.1. The Most Upstream Dike Breach Location

From the hydraulic modeling results (Section 5.1), it was found that dike breaches only occur at the most upstream dike breach location if the peak value of the upstream discharge wave is larger than 17,100 m3/s. However, the NARX models are sensitive to any change in the input parameter. Even a small change in the upstream discharge results in a different response of the NARX network. Consequently, the NARX network always produces a nonzero discharge prediction (Figure 9a). This finding explains the data points clustered around the T = 0 location in Figure 7. However, the predicted discharges are irrelevant for flood forecasting purposes since they are extremely low.

Figure 9.

(a–c) Multiple outflow hydrographs at the most upstream dike breach location predicted by the hydraulic model and the NARX network as a result of the upstream discharge waves presented in Figure 8.

For upstream discharges with a peak value larger than 17,100 m3/s, the predicted outflow hydrograph of the NARX network closely resembles those of the hydraulic model output (Figure 9b,c). The timing of the maximum discharge outflow is predicted quite accurately. The exact timing of the peak was shifted one time step, meaning that the peak occurs one hour later in the NARX predictions compared to the hydraulic model output. This explains the data points clustered around Y = 0 in Figure 7. If a more accurate timing of the peak outflow is required, this can easily be solved by decreasing the time step of the input and output data used to train the ANN to, for example, 1 min. Furthermore, the shape of the outflow hydrograph in the falling stage is correctly predicted by the NARX network (Figure 9).

Even though the shape of the outflow hydrographs are predicted accurately, the peak value is underpredicted with −27.9% on average for the most upstream breach location. Multiple loss functions were considered during the training procedure of the networks. However, all showed a similar, or even worse, pattern. A well-known problem with neural networks in general is that they are prone to systematic underprediction of flood series for extreme flood events. This underprediction can be reduced by, for example, postprocessing the NARX predictions by applying an unscented Kalman filter [34].

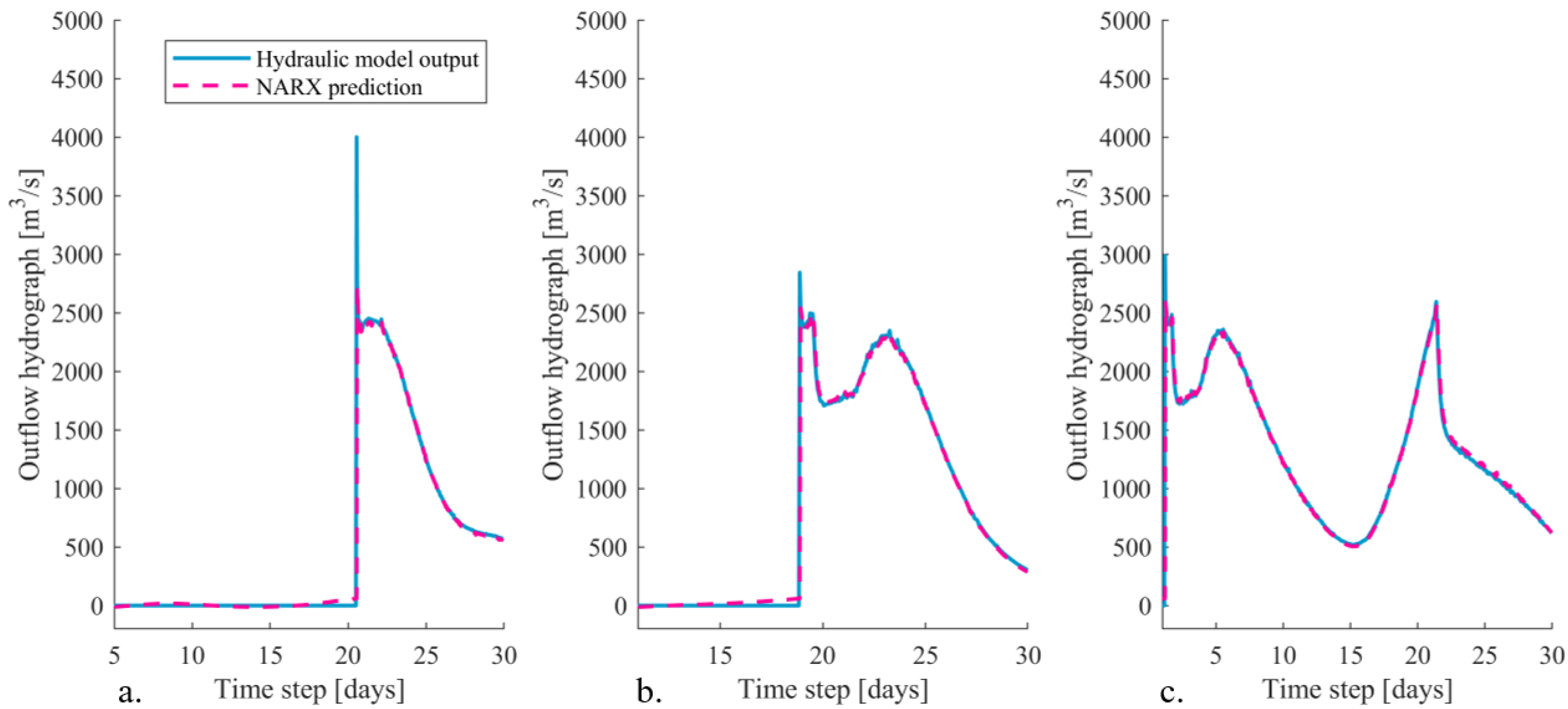

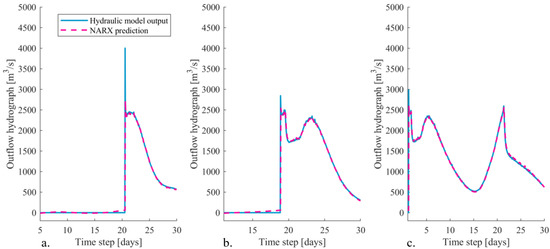

5.3.2. The IJssel River Dike Breach Location

Figure 10 shows multiple outflow hydrographs at the IJssel river dike breach location as predicted by the NARX network and the hydraulic model. It was found that the NARX network is capable of predicting the shape of the outflow hydrographs accurately. This also applies when the peak of the upstream discharge wave is larger than 17,100 m3/s. For these cases, the most upstream dike section breached as well influencing the shape of the discharge wave traveling in downstream direction through the river system and, consequently, the outflow hydrograph at the IJssel river (Section 5.1). This shows that the NARX network is capable of correctly identifying the system behavior. As a result, the NARX network is able to establish a relation between the upstream discharge wave and outflow hydrographs, even if the shape of this discharge wave changes in the river system due to other dike breaches. This finding shows the capabilities of using neural networks as an early flood forecasting system in a bifurcating river system where the dynamics due to multiple dike breaches are highly complex.

Figure 10.

(a–c) Multiple outflow hydrographs at the IJssel river dike breach location predicted by the hydraulic model and the NARX network as a result of the upstream discharge waves presented in Figure 8.

Furthermore, we found similar deviations in the predicted outflow hydrograph shapes at the IJssel river as was found for the most upstream dike breach location, namely prediction of small outflow discharges before the dike has failed and a shift of one time step in the timing of the peak value. However, the underprediction of the peak outflow discharge was less severe for the IJssel river breach location compared to the upstream breach location. For the IJssel river breach location, the peaks were underpredicted with 3.5% on average. This is mainly the result of the altered outflow hydrograph if the upstream breach location fails. For these situations, no extreme peak is present in the outflow hydrograph of the IJssel river (Figure 10b,c). However, if the upstream dike breach location does not fail, an extreme peak with a duration of one time step is present, again resulting in underprediction of this peak value of at maximum 21.2% (Figure 10a).

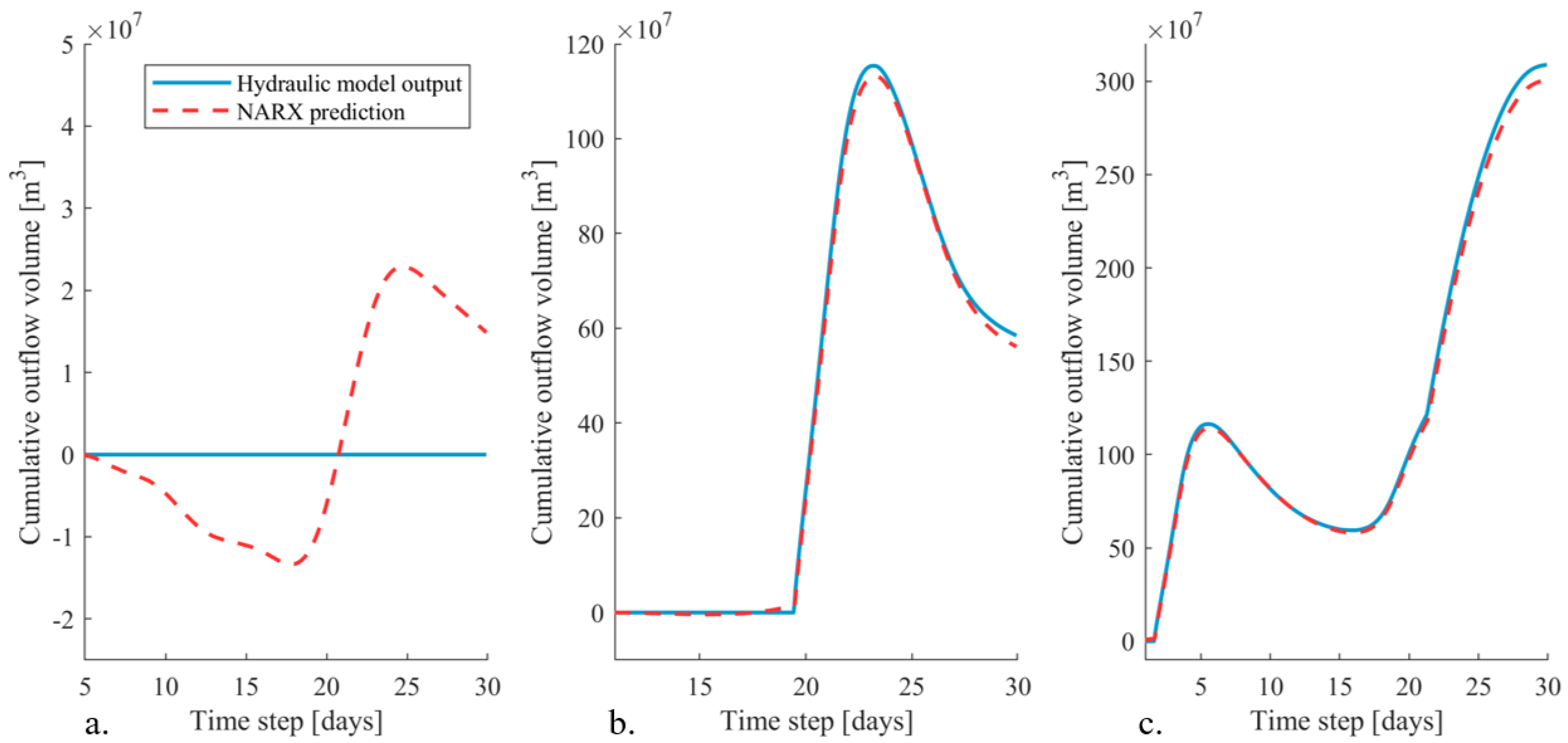

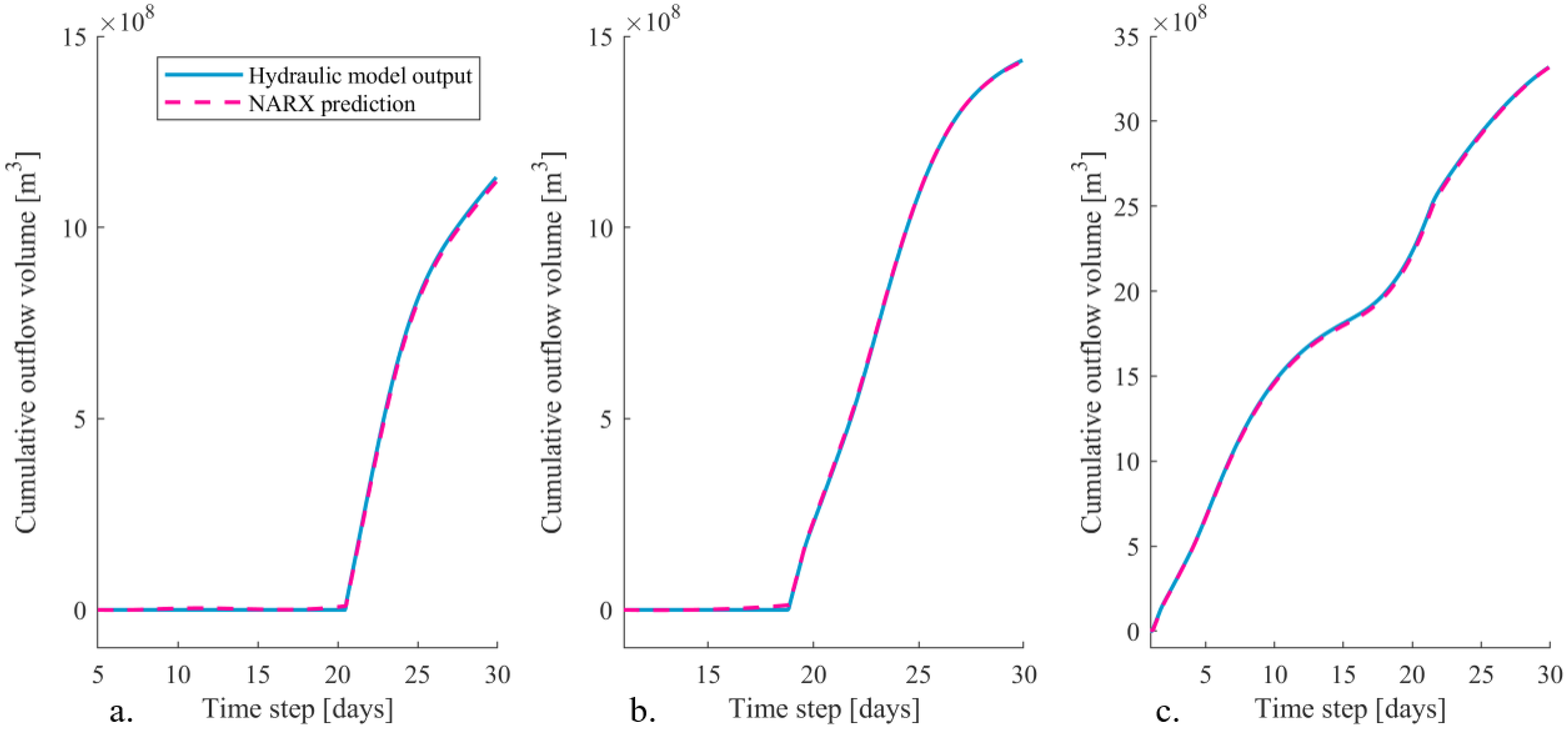

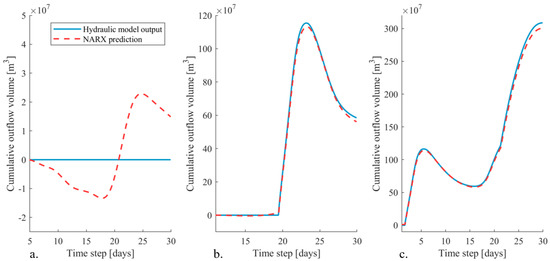

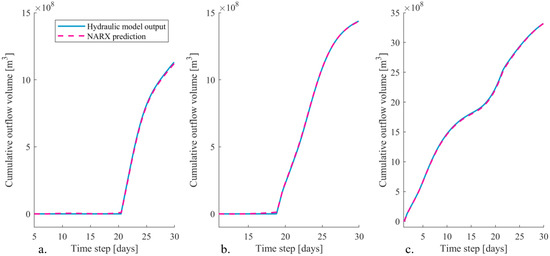

5.4. Prediction of the Outflow Hydrograph Volumes

For proper flood evacuation plans, not only the timing of a dike breach is important, but the total flood volume that may flow into the hinterland is also important since this largely determines the flood extent in the hinterland. Section 5.3 showed that the NARX networks underpredicted the peak outflow discharge, especially for the upstream breach location. However, since this peak discharge only occurred for a short moment in time just after the dike breached, this underprediction has almost no effect on the total outflow flood volume (Figure 11 and Figure 12). On average, the NARX networks predict a total flood volume which is around 1.67% and 1.32% lower compared to the hydraulic model predictions for the most upstream and IJssel river breach location, respectively. Besides the total flood volume, the cumulative flood volume over time is also predicted accurately (Figure 11 and Figure 12).

Figure 11.

(a–c) The cumulative outflow volume over time for the upstream breach location predicted by the hydraulic model and the NARX network as a result of the upstream discharge waves presented in Figure 8.

Figure 12.

(a–c) The cumulative outflow volume over time for the IJssel river breach location predicted by the hydraulic model and the NARX network as a result of the upstream discharge waves presented in Figure 8.

Furthermore, Section 5.3 showed that the NARX networks always computes an outflow discharge, even if the dike has not failed yet. Even though the computed outflow discharges are low, it still results in a cumulative outflow volume in the order of 2 × 107 m3 (Figure 11a). This incorrect predicted outflow volume can be confused with a dike breach if these networks are used by decision-makers in case of crisis situations. Therefore, it is recommended to postprocess the neural network predictions by including a threshold. Only if the outflow discharge exceeds this specific threshold, the specific dike section should be identified as a dike failure and corresponding outflow volume should be computed.

6. Discussion

This study showed the potential of NARX networks to be used to predict multiple outflow hydrographs of potential dike breaches in a bifurcating river system. This approach has the potential to be extended to a real-time flood forecasting system that is also capable of predicting inundation extents to set up evacuation plans. In reality, a flood event and corresponding consequences are highly uncertain and probabilistic of nature. However, assumptions were made in the current approach to reduce the complexity of the system. These assumptions are addressed in more detail below.

6.1. Critical Water Levels

Dikes can fail due to various mechanisms (e.g., overtopping, piping, macrostability), making the critical water level highly uncertain. In this study, it was assumed that the various potential dike breach locations could only fail due to the failure mechanism overtopping. For this failure mechanism, the critical water levels were assumed to be equal to the dike crest levels and, subsequently, the neural networks were able to accurately predict the dike breach locations. However, this critical water level is highly uncertain. Furthermore, for other failure mechanisms such as piping and macrostability, the critical water level can be substantially lower than currently considered. For future research, we aim to extend the current deterministic approach by including critical water levels in a probabilistic manner (e.g., [2,21,41,42]). Using such a probabilistic approach increases the complexity of the system significantly. Now, only two out of the 28 potential dike breach locations failed. Furthermore, the IJssel river dike breach location always failed earlier than the most upstream dike breach location since constant critical water levels were assumed. More dike sections may breach and the order in which the various dike sections fail may change by including multiple failure mechanisms randomly. This increase in the system complexity may require additional feedback layers in the NARX network setups. An option could be to update the water levels in the various river branches due to potential dike breaches during the NARX predictions. As a consequence, the interaction between critical water levels, dike breaches, and upstream and downstream water levels can be considered. How such a NARX network should be set up in detail is recommended for future research.

Furthermore, the critical water levels may change over time. Dike reinforcements are expected at the locations currently identified as potential dike breaches during flood events. If flood probability reduction measures are taken (e.g., dike reinforcements, floodplain widening, construction of a side channel), the NARX networks should be retrained. NARX networks, and data-driven models in general, do not have any physical interpretation. Instead, they are based on the input–output relations of a physically-based model. Therefore, new training data must be created with an updated hydraulic model representing the correct river schematization.

6.2. Infinitely High Dikes

In this study, water could only leave the river system if a dike breached. Overflow was not included in the analysis, assuming infinitely high dikes to reduce the complexity of the system. The considered dike breach locations did not always have the lowest crest level in a specific dike section. Therefore, in reality, overflow may have already happened at surrounding dike sections before a specific dike section failed. However, it is expected that the neural networks are also able to accurately predict outflow hydrographs in case overflow is included since the NARX neural networks have been shown to be able to include the spatial relations present in the system in terms of a changing discharge wave in downstream direction.

6.3. Toward an Early Flood Forecasting System

The NARX neural networks developed in this study only predicted outflow hydrographs. Inundation extents in the hinterland were not predicted, whereas a fast and accurate overview of the inundated areas helps to set up proper evacuation schemes. With the predicted outflow hydrographs, it was possible to compute the total flood volume entering the hinterland. These flood volumes should be transferred to inundation extents. Determination of how this can be efficiently performed using neural networks is recommended as an objective of future work.

7. Conclusions

During extreme flood events, dikes may fail, causing inundations in the hinterland and, consequently, flood damage. Early flood warning systems can help to mitigate the consequences of large flood events. In this study, NARX neural networks were developed for the potential dike breach locations in the Dutch Rhine river system. These NARX networks were able to predict if a specific dike section will fail and corresponding outflow hydrographs accurately. The timing of these dike failures was accurately predicted. Even though the maximum outflow discharges were slightly underpredicted, which is a common phenomena of neural networks under extreme conditions, the total outflow volumes only deviated with 1.67% and 1.31%, on average, for the two breach locations. These outflow volumes have the potential to be used to predict inundation extents in the hinterland, which is recommended to be included in the neural network setups for future research. Furthermore, various failure mechanisms should be included in future work to enable even more realistic prediction of the dike breach locations. By doing so, NARX neural networks have great potential to be used within the early flood warning system in the future.

Funding

This research is supported by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO, project 14506), which is partly funded by the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Policy. Furthermore, the research is supported by the Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management and Deltares.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Restrictions apply to the availability of the input data. Data was obtained from the Dutch Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management and the Landesamt für Natur, Umwelt und Verbraucherschutz (LANUV) of Northrhine-Westfalia and are available from the author with the permission of the Dutch Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the Dutch Ministry of Infrastructure for providing the data. Furthermore, the author would like to thank Suzanne Hulscher from the University of Twente for her valuable suggestions and the two reviewers for their feedback which greatly improved the quality of the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ | Directory of Open Access Journals |

| NARX network | Nonlinear autoregressive with external input neural network |

References

- Bradzil, R.; Kundziewics, Z.W.; Benito, G. Historical hydrology for studying flood risk in Europe. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2006, 51, 739–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bomers, A.; Schielen, R.M.J.; Hulscher, S.J.M.H. Consequences of dike breaches and dike overflow in a bifurcating river system. Nat. Hazards 2019, 97, 309–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leandro, J.; Chen, A.S.; Schumann, A. A 2D parallel diffusive wave model for floodplain inundation with variable time step (P-DWave). J. Hydrol. 2014, 517, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya Quiroga, V.; Kure, S.; Udo, K.; Mano, A. Application of 2D numerical simulation for the analysis of the February 2014 Bolivian Amazonia flood: Application of the new HEC-RAS version 5. Ribagua 2016, 3, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razavi, S.; Tolson, B.A.; Burn, D.H. Review of surrogate modeling in water resources. Water Resour. Res. 2012, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, C.W.; Wilby, R.L. Hydrological modelling using artificial neural networks. Prog. Phys. Geogr. 2001, 25, 80–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dibike, Y.B.; Solomatine, D.P. River Flow Forecasting Using Artificial Neural Network. Phys. Chem. Earth 2001, 26, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.Y.; Chang, L.C. Online multistep-ahead inundation depth forecasts by recurrent NARX networks. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2013, 17, 935–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campolo, M.; Soldati, A.; Andreussi, P. Artificial neural network approach to flood forecasting in the River Arno. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2003, 48, 381–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsafi, S.H. Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) for flood forecasting at Dongola Station in the River Nile, Sudan. Alex. Eng. J. 2014, 53, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekkas, D.F.; Onof, C.; Lee, M.J.; Baltas, E.A. Application of Artificial Neural Networks for Flood Forecasting. Glob. Nest Int. J. 2004, 6, 209–215. [Google Scholar]

- Laio, F.; Porporato, A.; Revelli, R.; Ridolfi, L. A comparison of nonlinear flood forecasting methods. Water Resour. Res. 2003, 39, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerh, T.; Lee, C.S. Neural networks forecasting of flood discharge at an unmeasured station using river upstream information. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2006, 37, 533–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bomers, A.; Van der Meulen, B.; Schielen, R.J.M.; Hulscher, S.J.M.H. Historic flood reconstruction with the use of an Artificial Neural Network. Water Resour. Res. 2019, 55, 9673–9688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooshyaripor, F.; Tahershamsi, A.; Behzadian, K. Estimation of Peak Outflow in Dam Failure Using Neural Network Approach under Uncertainty Analysis. Water Resour. 2015, 42, 721–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nourani, V.; Hakimzadeh, H.; Amini, A.B. Implementation of artificial neural network technique in the simulation of dam breach hydrograph. J. Hydroinform. 2012, 14, 478–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooijer, A.; Klijn, F.; Pedroli, G.B.M.; van Os, A.G. Towards sustainable flood risk management in the Rhine and Meuse river basins: Synopsis of the findings of IRMA-SPONGE. River Res. Appl. 2004, 20, 343–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spruyt, A.; Asselman, N. Afvoerverdeling Rijntakken: Eenvoudig Regelbaar of Niet? Technical Report, Project 11200539-000; Deltares: Delft, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Brunner, G.W. HEC-RAS, River Analysis System Hydraulic Reference Manual, Version 5.0; Technical Report February; US Army Corp of Engineers, Hydrologic Engineering Center (HEC): Davis, CA, USA, 2016.

- Apel, H.; Thieken, A.H.; Merz, B.; Blöschl, G. Flood risk assessment and associated uncertainty. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2004, 4, 295–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bruijn, K.M.; Diermanse, F.L.M.; Beckers, J.V.L. An advanced method for flood risk analysis in river deltas, applied to societal flood fatality risk in the Netherlands. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2014, 14, 2767–2781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, G.W. Combined 1D and 2D Modeling with HEC-RAS; Technical Report; Hydrologic Engineering Centre (HEC) of the US Army Crops of Engineers: Davis, CA, USA, 2014.

- Tijssen, A. Herberekening Werklijn Rijn in het Kader van WTI2011; Technical Report; Deltares: Delft, The Netherlands, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hegnauer, M.; Beersma, J.J.; van den Boogaard, H.F.P.; Buishand, T.A.; Passchier, R.H. Generator of Rainfall and Discharge Extremes (GRADE) for the Rhine and Meuse Basins. Final Report of GRADE 2.0; Technical Report; Deltares: Delft, The Netherlands, 2014; ISBN 9789036914062. [Google Scholar]

- Bomers, A.; Schielen, R.; Hulscher, S. Application of a lower-fidelity surrogate hydraulic model for historic flood reconstruction. Environ. Model. Softw. 2019, 117, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bomers, A.; Schielen, R.J.M.; Hulscher, S.J.M.H. Decreasing uncertainty in flood frequency analyses by including historic flood events in an efficient bootstrap approach. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2019, 19, 1895–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltelli, A.; Ratto, M.; Andres, T.; Campologno, F.; Cariboni, J.; Gatelli, D.; Saisana, M.; Tarantola, S. Global Sensitivity Analysis: The Primer; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2008; ISBN 978-0-470-05997-5. [Google Scholar]

- Campolo, M.; Andreussi, P.; Soldati, A. River flood forecasting with a neural network model. Water Resour. Res. 1999, 35, 1191–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kia, M.B.; Pirasteh, S.; Pradhan, B.; Mahmud, A.R.; Sulaiman, W.N.A.; Moradi, A. An artificial neural network model for flood simulation using GIS: Johor River Basin, Malaysia. Environ. Earth Sci. 2012, 67, 251–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, R.; Schmitz, G.; Cullmann, J. Flood routing modelling with Artificial Neural Networks. Adv. Geosci. 2006, 9, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, R.R.; Theobald, S.; Nestmann, F. Simulation of flood flow in a river system using artificial neural networks. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. Discuss. 2005, 9, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunsch, A.; Liesch, T.; Broda, S. Forecasting groundwater levels using nonlinear autoregressive networks with exogenous input (NARX). J. Hydrol. 2018, 567, 743–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rjeily, Y.A.; Abbas, O.; Sadek, M.; Shahrour, I.; Chehade, F.H. Flood forecasting within urban drainage systems using NARX neural network. Water Sci. Technol. 2017, 76.9, 2401–2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Guo, S.; Xu, C.Y.; Chanf, F.J.; Yin, J. Improving the Reliability of Probabilistic Multi-Step-Ahead Flood Forecasting by Fusing Unscented Kalman Filter with Recurrent Neural Network. Water 2020, 12, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagan, M.T.; Menhaj, M.B. Training Feedforward Networks with the Marquardt Algorithm. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 1994, 5, 989–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, C.; Ding, S.Q.; Lee, T.H. Geometrical interpretation and architecture selection of MLP. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 2005, 16, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulibaly, P.; Anctil, F.; Bobée, B. Daily reservoir inflow forecasting using artificial neural networks with stopped training approach. J. Hydrol. 2000, 230, 244–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourakis, M.I. A brief description of the Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm implemented Levmar. Found. Res. Technol. 2005, 4, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Nash, J.E.; Sutcliffe, J.V. River flow forecasting through conceptual models. Part 1. A discussion of principles. J. Hydrol. 1970, 10, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, P.; Boyle, D.P.; Bäse, F. Comparison of different efficiency criteria for hydrological model assessment. Adv. Geosci. 2005, 5, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apel, H.; Merz, B.; Thieken, A.H. Influence of dike breaches on flood frequency estimation. Comput. Geosci. 2009, 35, 907–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorogushyn, S.; Apel, H.; Merz, B. The impact of the uncertainty of dike breach development time on flood hazard. Phys. Chem. Earth 2011, 36, 319–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).