Decoding LSTM to Reveal Baseflow Contributions in Fractured and Sedimentary Mountain Basins: A Case Study in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, Southwestern United States

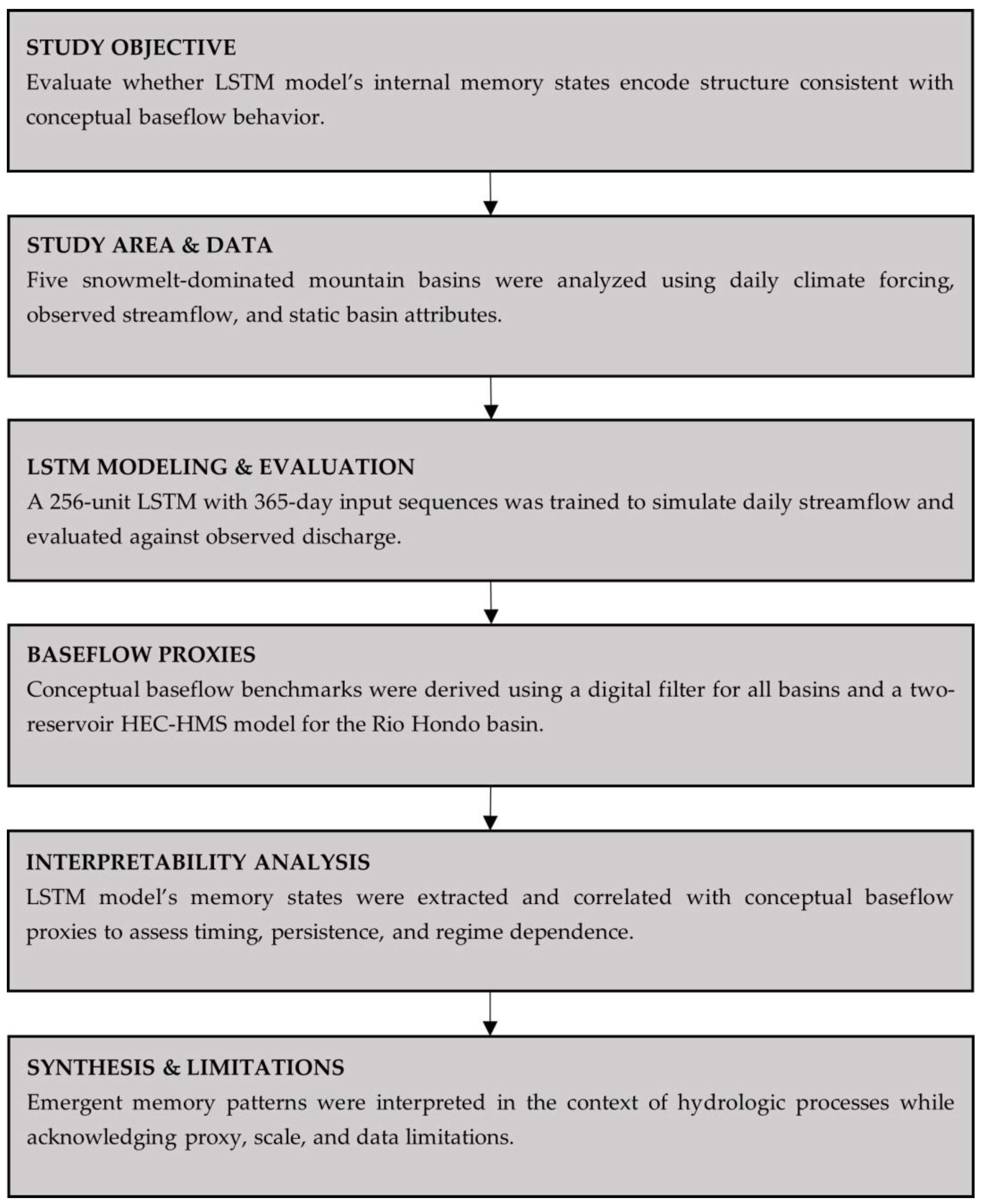

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (RQ1) Can LSTM models trained solely on meteorological and hydrologic inputs develop internal memory representations that are statistically and conceptually consistent with physically derived baseflow components in snowmelt-dominated mountain basins?

- (RQ2) Do distinct LSTM states preferentially align with fast and slow groundwater response regimes, as represented by conceptual baseflow models and independent hydrochemical classifications?

- (RQ3) How does the representation of baseflow-related memory states change under contrasting hydroclimatic conditions, particularly during extended drought periods when groundwater contributions dominate streamflow?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Model Architecture and Training

2.3. Performance Metrics

2.4. Finetuning

3. Results

3.1. Model Performance

3.2. Uncertainty Analysis

3.3. Baseflow Index Behavior Under Drought and Pre-Drought Conditions

3.4. Evaluating LSTM States Against Simulated Baseflow Components

4. Discussion

4.1. Correlation with Evolved Groundwater Study

4.2. Implications for Interpretability and Water Management

4.3. Wildfire Disturbances

4.4. Context and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| XAI | Explainable Artificial Intelligence |

| HEC-HMS | Hydrologic Engineering Center’s Hydrologic Modeling System |

| EMMA | End-Member Mixing Analysis |

| GMM | Gaussian Mixture Model |

| NPS | National Parks Service |

| DHWBDP | Daily Historical Water Balance Data Product |

| SWE | Snow Water Equivalent |

| USGS | United States Geological Survey |

| BFI | Baseflow Index |

| NLCD | National Land Cover Database |

| SSURGO | Soil Survey Geographic Database |

| NSE | Nash-Sutcliffe Efficiency |

| ATI | Antecedent Temperature Index |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| NRMSE | Normalized Root Mean Square Error |

| PBIAS | Percent Bias |

| R2 | Coefficient of Determination |

| KGE | Kling-Gupta Efficiency |

| FMS | Medium flow bias |

| FLV | Low flow bias |

| FDC | Flow Duration Curve |

| Quantile-Quantile | |

| NDMC | National Drought Mitigation Center |

| PCA | Principle Component Analysis |

| NDVI | Normalized Difference Vegetation Index |

References

- Carroll, R.; Manning, A.H.; Niswonger, R.G.; Marchetti, D.W.; Williams, K.H. Baseflow age distributions and depth of active groundwater flow in a snow-dominated mountain headwater basin. Water Resour. Res. 2020, 56, e2020WR028161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godsey, S.E.; Kirchner, J.W.; Tague, C. Effects of changes in winter snowpacks on summer low flows: Case studies in the Sierra Nevada, California, USA. Hydrol. Process. 2013, 28, 5048–5064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilling, O.S.; Parajuli, A.; Otis, C.T.; Müller, T.; Quijano, W.A.; Tremblay, Y.; Therrien, R. Quantifying groundwater recharge dynamics and unsaturated zone processes in snow-dominated catchments via on-site dissolved gas analysis. Water Resour. Res. 2021, 57, e2020WR028479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tennant, C.; Larsen, L.G.; Bellugi, D.; Moges, E.; Zhang, L.; Ma, H. The utility of information flow in formulating discharge forecast models: A case study from an arid snow-dominated catchment. Water Resour. Res. 2020, 56, e2019WR024908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huntington, J.; Niswonger, R.G. Role of surface-water and groundwater interactions on projected summertime streamflow in snow-dominated regions: An integrated modeling approach. Water Resour. Res. 2012, 48, W11503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisbee, M.D.; Tolley, D.G.; Wilson, J.L. Field estimates of groundwater circulation depths in two mountainous watersheds in the western US and the effect of deep circulation on solute concentrations in streamflow. Water Resour. Res. 2017, 53, 2693–2715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, P.D.; Solomon, D.K.; Kampf, S.; Warix, S.; Bern, C.; Barnard, D.; Barnard, H.R.; Carling, G.T.; Carroll, R.W.H.; Chorover, J.; et al. Groundwater dominates snowmelt runoff and controls streamflow efficiency in the western United States. Commun. Earth Environ. 2025, 6, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisbee, M.D.; Phillips, F.M.; White, A.F.; Campbell, A.R.; Liu, F. Effect of source integration on the geochemical fluxes from springs. Appl. Geochem. 2013, 28, 32–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajami, H.; Troch, P.A.; Maddock, T. Quantifying mountain block recharge by means of catchment-scale storage–discharge relationships. Water Resour. Res. 2011, 47, W04507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciruzzi, D.M.; Lowry, C.S. Impact of complex aquifer geometry on groundwater storage in high-elevation meadows of the Sierra Nevada Mountains, California. Hydrol. Process. 2017, 31, 1565–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werth, S.; Shirzaei, M.; Carlson, G.; Bürgmann, R. Connecting Deep Aquifer Recharge in California’s Central Valley to Sierra Nevada Snowmelt via Multi-Sensor Remote Sensing Data. EGUsphere 2025, 2025, 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, L.; Kuang, X.; Or, D.; Zheng, C. Streamflow Composition and Water “Imbalance” in the Northern Himalayas. Water Resour. Res. 2023, 59, e2022WR034243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luce, C.H.; Holden, Z.A. Declining annual streamflow distributions in the Pacific Northwest United States, 1948–2006. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2009, 36, L16401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, A.H.; Solomon, D.K. An integrated environmental tracer approach to characterizing groundwater circulation in a mountain block. Water Resour. Res. 2005, 41, W12403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Tang, Q.; Zhao, G.; Gao, L.; Shen, C.; Pan, B. Physics-Guided Long Short-Term Memory Network for Streamflow and Flood Simulations in the Lancang–Mekong River Basin. Water 2022, 14, 1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Yang, Q. Applying Machine Learning Methods to Improve Rainfall–Runoff Modeling in Subtropical River Basins. Water 2024, 16, 2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Chen, X.; Du, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, Q.; Ma, Y. Enhancing long short-term memory (LSTM)-based streamflow prediction with a spatially distributed approach. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2024, 28, 2107–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, K.M.R.; Brown, J.D.; Jones, S.A.; Liu, Z. Using a long short-term memory (LSTM) neural network to boost river streamflow forecasts over the western United States. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2022, 26, 5449–5472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kratzert, F.; Klotz, D.; Herrnegger, M.; Sampson, A.K.; Hochreiter, S.; Nearing, G.S. Rainfall–runoff modelling using long short-term memory (LSTM) networks. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2018, 22, 6005–6022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solanki, H.; Vegad, U.; Kushwaha, A.P.; Mishra, V. Improving streamflow prediction using multiple hydrological models and machine learning methods. Water Resour. Res. 2025, 61, e2024WR038192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yifru, B.A.; Lim, K.J.; Lee, S. Enhancing streamflow prediction physically consistently using process-based modeling and domain knowledge: A review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lees, T.; Chaney, N.; Nearing, G.S.; Xu, Y.; Klotz, D.; Kratzert, F. Hydrological concept formation inside long short-term memory (LSTM) networks. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. Discuss. 2021, 26, 3079–3101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, D.; Fang, K.; Shen, C. Enhancing streamflow forecast and extracting insights using long short-term memory networks with data integration at continental scales. Water Resour. Res. 2020, 56, e2019WR026793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Wu, Q.; Li, H.; Jian, S.; Li, N.; Lou, Z. Deep learning with a long short-term memory networks approach for rainfall–runoff simulation. Water 2018, 10, 1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kratzert, F.; Klotz, D.; Shalev, G.; Klambauer, G.; Hochreiter, S.; Nearing, G. Towards learning universal, regional, and local hydrological behaviors via machine learning applied to large-sample datasets. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2019, 23, 5089–5110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangukiya, N.K.; Sharma, A. Deep learning-based approach for enhancing streamflow prediction in watersheds with aggregated and intermittent observations. Water Resour. Res. 2024, 61, e2024WR037331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, S.; Radić, V. Interpreting deep machine learning for streamflow modeling across glacial, nival, and pluvial regimes in southwestern Canada. Front. Water 2022, 4, 934709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez, J.; Cortés, C.B.; Yáñez, M.A. Explainable artificial intelligence in hydrology: Interpreting black-box snowmelt-driven streamflow predictions in an arid Andean basin of north-central Chile. Water 2023, 15, 3369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, S.G.; Pradhanang, S.M. Performance of LSTM over SWAT in rainfall–runoff modeling in a small, forested watershed: A case study of Cork Brook, RI. Water 2023, 15, 4194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraft, B.; Jung, M.; Körner, M.; Koirala, S.; Reichstein, M. Towards hybrid modeling of the global hydrological cycle. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2022, 26, 1579–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, D.C.; Kayastha, R.B.; Shrestha, K.L.; Kayastha, R.B. A hybrid approach to enhance streamflow simulation in data-constrained Himalayan basins: Combining the glacio-hydrological degree-day model and recurrent neural networks. Proc. IAHS 2024, 387, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bales, R.C.; Molotch, N.P.; Painter, T.H.; Dettinger, M.D.; Rice, R.; Dozier, J. Mountain hydrology of the western United States. Water Resour. Res. 2006, 42, W08432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, A.H.; Solomon, D.K.; Sheldon, A.L. Applications of a total dissolved gas pressure probe in ground water studies. Groundwater 2003, 41, 440–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smerdon, B.D.; Gardner, W.P.; Harrington, G.A.; Tickell, S.J. Identifying the contribution of regional groundwater to the baseflow of a tropical river (Daly River, Australia). J. Hydrol. 2012, 464–465, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolley, D.G. High-Elevation Mountain Streamflow Generation: The Role of Deep Groundwater in the Rio Hondo Watershed, Northern New Mexico. Ph.D. Thesis, New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology, Socorro, NM, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Huijgevoort, M.v.; Hazenberg, P.; Lanen, H.v.; Uijlenhoet, R. A generic method for hydrological drought identification across different climate regions. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2012, 16, 2437–2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wigington, P.J.; Leibowitz, S.G.; Comeleo, R.L.; Ebersole, J.L. Oregon hydrologic landscapes: A classification framework. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2012, 49, 163–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). Groundwater in the Cimarron River Basin, New Mexico, Colorado, Kansas, and Oklahoma; U.S. Geological Survey: Washington, DC, USA, 1966; Open-File Report 66–159; p. 51. Available online: https://pubs.usgs.gov/publication/ofr66159 (accessed on 16 June 2020).

- Spiegel, Z.; Baldwin, B. Geology and Water Resources of the Santa Fe Area, New Mexico; Geological Survey Water-Supply Paper 1525; U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 1963.

- Bauer, P.W.; Johnson, P.S.; Kelson, K.I. Geology and Hydrogeology of the Southern Taos Valley, Taos County, New Mexico; Final Technical Report; New Mexico Office of the State Engineer: Santa Fe, NM, USA, 1999; p. 56.

- Smith, J.F., Jr.; Ray, L.L. Geology of the Cimarron Range, New Mexico. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 1943, 54, 891–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodknight, C.S. Cenozoic structural geology of the central Cimarron Range, New Mexico. In Guidebook of the 27th Field Conference, New Mexico Geological Society; New Mexico Geological Society: Socorro, NM, USA, 1976; Volume 27, pp. 137–140. [Google Scholar]

- Kratzert, F.; Hochreiter, S.; Klotz, D.; Brandstetter, J.; Mayr, A.; Klambauer, G. NeuralHydrology—A Python library for deep learning research in hydrology. J. Open Source Softw. 2022, 7, 4050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NeuralHydrology. GMM—NeuralHydrology Documentation. Available online: https://neuralhydrology.readthedocs.io/en/latest/usage/models.html#gmm (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Ha, D. Mixture Density Networks with Tensorflow. Available online: http://blog.otoro.net/2015/11/24/mixture-density-networks-with-tensorflow (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- PyTorch. AdamW—PyTorch 2.8 Documentation. Available online: https://pytorch.org/docs/stable/generated/torch.optim.AdamW.html (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- NeuralHydrology. GMM Loss—NeuralHydrology Documentation. Available online: https://neuralhydrology.readthedocs.io/en/latest/api/neuralhydrology.training.loss.html#module-neuralhydrology.training.loss (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Li, Q.; Zhao, T. Role of the Water Balance Constraint in the Long Short-Term Memory Network: Large-Sample Tests of Rainfall–Runoff Prediction. EGUsphere 2024, 2024, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mena, J.B.R.; Plaza, D.; Giraldo, E. Multivariate hydrological modelling based on long short-term memory networks for water level forecasting. Information 2024, 15, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.; Fang, F.; Pain, C.C.; Navon, I.M. Rapid spatio-temporal flood prediction and uncertainty quantification using a deep learning method. J. Hydrol. 2019, 575, 911–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpatne, A.; Atluri, G.; Faghmous, J.H.; Steinbach, M.; Banerjee, A.; Ganguly, A.R.; Kumar, V. Theory-guided data science: A new paradigm for scientific discovery from data. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2017, 29, 2318–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, S.; Li, J.; Chai, Y.; Liu, L.; Sivapalan, M.; Ran, Q. Using explainable artificial intelligence as a diagnostic tool for hydrological modeling. EGUsphere 2025. preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, W.; Feng, D.; Pan, M.; Beck, H.E.; Lawson, K.; Yang, Y.; Shen, C. From calibration to parameter learning: Harnessing the scaling effects of big data in geoscientific modeling. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceni, A.; Ashwin, P.; Livi, L. Interpreting recurrent neural networks behaviour via excitable network attractors. Cogn. Comput. 2019, 12, 330–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enel, P.; Procyk, E.; Quilodran, R.; Dominey, P.F. Reservoir computing properties of neural dynamics in prefrontal cortex. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2016, 12, e1004967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, S.R.; Fu, G.; Janardhanan, S. Explainable AI for interpreting spatiotemporal groundwater predictions. Water Resour. Res. 2025, 61, e2025WR041303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tercek, M.T.; Gross, J.E.; Thoma, D.P. Robust projections and consequences of an expanding bimodal growing season in the western United States. Ecosphere 2023, 14, e4530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyal, A.; Versteeg, R.; Alper, E.; Johnson, D.; Rodzianko, A.; Franklin, M.; Wainwright, H. Automated cloud-based long short-term memory neural network-based SWE prediction. Front. Water 2020, 2, 574917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, T.H.; Pomeroy, J.W.; Wheater, H.S.; Baulch, H.M. Hydrological responses to climatic variability in a cold agricultural region. Hydrol. Process. 2016, 31, 854–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Pomeroy, J.W. Snowmelt runoff sensitivity analysis to drought on the Canadian prairies. Hydrol. Process. 2007, 21, 2594–2609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, D.; Roste, J.; Pomeroy, J.W.; Baulch, H.M.; Elliott, J.G.; Wheater, H.S.; Westbrook, C.J. A modelling framework to simulate field-scale nitrate response and transport during snowmelt: The WINTRA model. Hydrol. Process. 2017, 31, 4250–4268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, K.; Jennings, K.S.; Musselman, K.N.; Livneh, B.; Molotch, N.P. Recent decreases in snow water storage in western North America. Commun. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkouk, A.; Pokhrel, Y.; Livneh, B.; Payton, E.A.; Luo, L.; Cheng, Y.; Thiery, W. Toward understanding parametric controls on runoff sensitivity to climate in the Community Land Model: A case study over the Colorado River headwaters. Water Resour. Res. 2024, 60, e2024WR037718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladson, T.R.; Brown, R.; Neal, B.; Nathan, R. A Standard Approach to Baseflow Separation Using The Lyne and Hollick Filter. Australas. J. Water Resour. 2013, 17, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Hydrologic Engineering Center. HEC-HMS Hydrologic Modeling System, User’s Manual, Version 4.0, CPD-74A; U.S. Army Corps of Engineers: Davis, CA, USA, 2013.

- Dewitz, J. National Land Cover Database (NLCD) 2021 Products; U.S. Geological Survey Data Release: Reston, VA, USA, 2023. [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service. Soil Survey Geographic (SSURGO) Database, Kenosha and Racine Counties, Wisconsin; National Cooperative Soil Survey: Fort Worth, TX, USA, 2004.

- Thornton, M.M.; Shrestha, R.; Wei, Y.; Thornton, P.E.; Kao, S.-C. Daymet: Daily Surface Weather Data on a 1-km Grid for North America, Version 4 R1; Oak Ridge National Laboratory DAAC: Oak Ridge, TN, USA, 2022. [CrossRef]

- U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Hydrologic Engineering Center. HEC-HMS Hydrologic Modeling System, User’s Manual, Version 4.13.0, CPD-74A; U.S. Army Corps of Engineers: Davis, CA, USA, 2024.

- Moriasi, D.N.; Arnold, J.G.; Van Liew, M.W.; Bingner, R.L.; Harmel, R.D.; Veith, T.L. Model evaluation guidelines for systematic quantification of accuracy in watershed simulations. Trans. ASABE 2007, 50, 885–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilbrand, K.; Kratzert, F.; Klotz, D.; Hochreiter, S.; Nearing, G.S. Predicting streamflow with LSTM networks using global datasets. Front. Water 2023, 5, 1166124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Drought Mitigation Center; U.S. Department of Agriculture; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. U.S. Drought Monitor. Available online: https://droughtmonitor.unl.edu (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Tóth, J. A theoretical analysis of groundwater flow in small drainage basins. J. Geophys. Res. 1963, 68, 4795–4812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisbee, M.D.; Phillips, F.M.; Campbell, A.R.; Liu, F.; Sanchez, S.A. Are we missing the tail (and the tale) of residence time distributions in watersheds? Geophys. Res. Lett. 2013, 40, 4633–4637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Hydrologic Engineering Center. HEC-HMS Hydrologic Modeling System, Technical Reference Manual, CPD-74B; U.S. Army Corps of Engineers: Davis, CA, USA, 2000.

- Christophersen, N.; Hooper, R.P. Multivariate analysis of stream flow chemistry data: The use of principal components for the end-member mixing problem. Water Resour. Res. 1992, 28, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Interagency Fire Center. U.S. National Interagency Fire Center. United States; 1998. Available online: https://www.loc.gov/item/lcwaN0031193/ (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Moody, J.A.; Martin, D.A. Post-fire, rainfall intensity–peak discharge relations for three mountainous watersheds in the western USA. Hydrol. Process. 2001, 15, 2981–2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebel, B.A.; Martin, D.A.; Moody, J.A.; McGuire, L.A.; Singer, M.B.; Brogan, D.J. Modeling post-wildfire hydrologic response: Review and future directions for applications of physically based distributed simulation. Earth’s Future 2023, 11, e2022EF003038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Basin Characteristics | Basin | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hondo | Lucero | Taos | Ponil | Rayado | |

| Latitude (Degrees) * | 36.54 | 36.51 | 36.44 | 36.57 | 36.37 |

| Longitude (Degrees) * | −105.56 | −105.53 | −105.5 | −104.95 | −104.97 |

| Mean Basin Slope (%) | 52 | 51 | 38 | 25 | 23 |

| Drainage Area (km2) | 96.35 | 43.77 | 163.43 | 481.74 | 158.51 |

| Mean Elevation (m, amsl †) | 3167.9 | 3268 | 2928.6 | 2617.9 | 2896.7 |

| Outlet Elevation (m, amsl †) | 2334.9 | 2459.3 | 2255.5 | 2024.7 | 2056.4 |

| Mean annual Precipitation (mm d−1) | 1.74 | 1.80 | 1.59 | 1.43 | 1.69 |

| Snow Fraction (%) ‡ | 41.11 | 42.52 | 35.27 | 27.18 | 20.60 |

| Mean Annual High Temp (°C) | 9.80 | 9.26 | 11.64 | 13.85 | 12.12 |

| Mean Annual Low Temp (°C) | −4.65 | −4.83 | −3.64 | −2.51 | −3.15 |

| Sequence Length | Dropout | Embedding Network * (FC Layers) | Hidden State Size | Batch Size | Initial Learning Rate | Learning Rate at Epoch 10 | Learning Rate at Epoch 20 | Learning Rate at Epoch 40 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 365 | 0.2 | 128–64–128 | 256 | 64 | 5.00 × 10−4 | 3.00 × 10−4 | 1.00 × 10−4 | 5.00 × 10−5 |

| Variable | Unit | Data Source |

|---|---|---|

| Precipitation | mm/day | Daymet |

| Daylight Seconds | Sec | Daymet |

| Shortwave Radiation | W/m2 | Daymet |

| Max Temperature | °C | Daymet |

| Min Temperature | °C | Daymet |

| Vapor Pressure | Pa | Daymet |

| Snow Water Equivalent | kg/m2 | Daymet |

| Observed flow | m3 s−1 | USGS |

| Latitude | Degrees | USGS |

| Longitude | Degrees | USGS |

| Elevation | Feet above Sea Level | USGS |

| Drainage Area | Acres | USGS |

| Surface Characteristics | NA | USGS |

| Accumulated Snow Water Equivalent | mm | DHWBDP |

| Actual Evapotranspiration | mm | DHWBDP |

| Potential Evapotranspiration | mm | DHWBDP |

| Deficit | mm | DHWBDP |

| Rain | mm | DHWBDP |

| Runoff | mm | DHWBDP |

| Soil water | mm | DHWBDP |

| Parameter | Unit | Model Year | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | ||

| Base Temperature | °C | 7.2 | 4.4 | 0.6 | 3.9 | 6.7 |

| Snow vs. Rain Temperature | °C | 0 | 0 | 1.1 | 0 | 0.6 |

| Rain Rate Limit | mm/h | 2.54 | 2.54 | 2.54 | 12.7 | 2.54 |

| Cold Limit | mm | 0.51 | 0.25 | 2.03 | 0.51 | 0.51 |

| ATI Coefficient | – | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.6 |

| GW-1 Baseflow Fraction | – | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.05 |

| GW-2 Baseflow Fraction | – | 0.09 | 0.1 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.07 |

| GW-1 Routing Coefficient | h | 1050 | 200 | 2200 | 600 | 300 |

| GW-2 Routing Coefficient | h | 1500 | 1000 | 2400 | 1000 | 1600 |

| Water Year | Mean Flow Obs. (m3/s) | Mean Flow Sim. (m3/s) | Max Flow Obs. (m3/s) | Max Flow Sim. (m3/s) | Volume (m3) | NSE | NRMSE | PBIAS (%) | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 0.371 | 0.366 | 1.133 | 0.814 | 11,683,000 | 0.81 | 0.44 | −1.25 | 0.81 |

| 2001 | 1.02 | 1.025 | 6.116 | 4.165 | 31,994,000 | 0.92 | 0.27 | 0.72 | 0.93 |

| 2002 | 0.259 | 0.251 | 0.453 | 0.456 | 7,677,000 | 0.39 | 0.8 | −3.29 | 0.51 |

| 2003 | 0.658 | 0.651 | 2.520 | 2.392 | 20,671,000 | 0.92 | 0.28 | −1.09 | 0.93 |

| 2004 | 0.568 | 0.566 | 2.237 | 2.058 | 17,876,000 | 0.9 | 0.32 | −0.21 | 0.9 |

| Basin | NSE | KGE | RMSE (m3 s−1) | Pearson-r | FMS (%) | FLV (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hondo | 0.88 | 0.75 | 0.36 | 0.78 | −0.07 | 0.90 | 0.96 | −3.36 | 67.24 |

| Lucero | 0.90 | 0.79 | 0.19 | 0.81 | −0.06 | 0.93 | 0.96 | −15.52 | 26.67 |

| Taos | 0.85 | 0.77 | 0.36 | 0.78 | −0.02 | 0.97 | 0.94 | −13.40 | 50.87 |

| Ponil | 0.49 | 0.37 | 0.61 | 0.57 | −0.16 | 0.63 | 0.74 | −30.72 | 58.05 |

| Rayado | 0.85 | 0.79 | 0.17 | 0.84 | −0.07 | 0.89 | 0.93 | −35.88 | 33.75 |

| Basin | NSE | KGE | RMSE (m3 s−1) | Pearson-r | FMS (%) | FLV (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hondo | 0.87 | 0.64 | 0.46 | 0.71 | −0.16 | 0.79 | 0.99 | −10.27 | 52.29 |

| Lucero | 0.89 | 0.68 | 0.25 | 0.73 | −0.13 | 0.83 | 0.99 | −6.82 | 41.24 |

| Taos | 0.94 | 0.78 | 0.26 | 0.79 | −0.06 | 0.91 | 0.99 | −10.11 | 22.97 |

| Ponil | 0.83 | 0.75 | 0.12 | 1.2 | 0.09 | 1.14 | 0.95 | −35.18 | −105.77 |

| Rayado | 0.95 | 0.92 | 0.06 | 0.93 | 0.01 | 1.01 | 0.98 | −20 | 78.48 |

| Basin | NSE | KGE | RMSE (m3 s−1) | Pearson-r | FMS (%) | FLV (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hondo | 0.90 | 0.92 | 0.15 | 1.01 | 0.06 | 1.06 | 0.95 | 5.14 | 77.84 |

| Lucero | 0.90 | 0.81 | 0.12 | 0.81 | 0.04 | 1.04 | 0.96 | −20.96 | 18.82 |

| Taos | 0.66 | 0.65 | 0.24 | 1.24 | 0.18 | 1.23 | 0.90 | −14.31 | 58.65 |

| Ponil | 0.35 | 0.2 | 0.71 | 0.41 | −0.13 | 0.58 | 0.65 | −55.17 | 60.64 |

| Rayado | 0.83 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 1.15 | 0.09 | 1.13 | 0.94 | −16.2 | 37.2 |

| Basin | Pre Drought BFI * | Drought BFI * | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed | Simulated | Observed | Simulated | |

| Hondo | 0.32 | 0.36 | 0.56 | 0.56 |

| Lucero | 0.32 | 0.36 | 0.51 | 0.56 |

| Taos | 0.28 | 0.32 | 0.44 | 0.47 |

| Ponil | 0.22 | 0.23 | 0.45 | 0.47 |

| Rayado | 0.36 | 0.39 | 0.21 | 0.29 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Rosati, M.; Lim, Y.H.; Zemlick, K.; Syed, K. Decoding LSTM to Reveal Baseflow Contributions in Fractured and Sedimentary Mountain Basins: A Case Study in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, Southwestern United States. Hydrology 2026, 13, 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrology13020051

Rosati M, Lim YH, Zemlick K, Syed K. Decoding LSTM to Reveal Baseflow Contributions in Fractured and Sedimentary Mountain Basins: A Case Study in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, Southwestern United States. Hydrology. 2026; 13(2):51. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrology13020051

Chicago/Turabian StyleRosati, Michael, Yeo H. Lim, Katie Zemlick, and Kamran Syed. 2026. "Decoding LSTM to Reveal Baseflow Contributions in Fractured and Sedimentary Mountain Basins: A Case Study in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, Southwestern United States" Hydrology 13, no. 2: 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrology13020051

APA StyleRosati, M., Lim, Y. H., Zemlick, K., & Syed, K. (2026). Decoding LSTM to Reveal Baseflow Contributions in Fractured and Sedimentary Mountain Basins: A Case Study in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, Southwestern United States. Hydrology, 13(2), 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrology13020051