Benefits and Challenges of Small Dams in Mediterranean Climate Region: A Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Literature Review

3. Results

3.1. Interdisciplinary Connections in Small Dam Studies

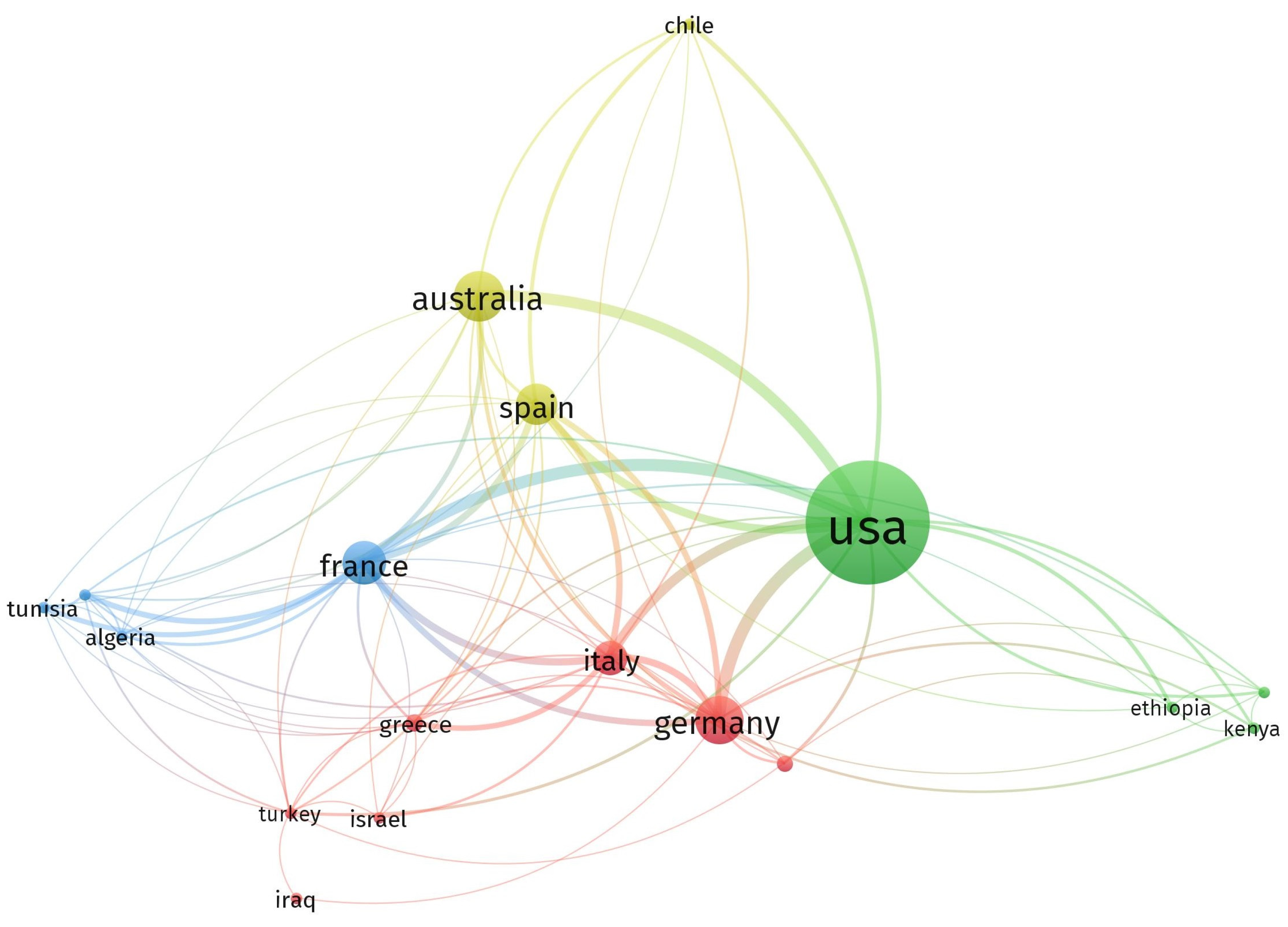

3.2. Global Collaboration Network on Small Dam Research

3.3. Selected Small Dam Case Studies

3.4. Benefits of Small Dams

3.5. Impacts and Challenges of Small Dams

| Author, Country | Purpose | Positive Aspect | Negative Aspects |

|---|---|---|---|

| [16]; GR | Combat water scarcity by building dry-stone micro-dams to recharge aquifers and reduce flood risk. | Groundwater recharge, flooding controls, increase in biodiversity, sustainable techniques, community involvement. | Needs maintenance, sediment build-up, and relies on continued community engagement. |

| [17]; ES | Investigate nutrient management and eutrophication control within a hypertrophic estuary | Phosphorus reduction and water quality improvements by trapping nutrients before the estuary | NA |

| [4]; MA | Assess siltation impacts on the Ahmed El Hansali dam due to land use and climate change | Provides water storage for irrigation, drinking, and power generation; local flood control | High siltation rates reduce water storage capacity. |

| [18]; TN | Analyze the relationship between dam efficiency, sedimentation, and the lithology of watersheds | Water storage, groundwater recharge | High sedimentation rates reduce reservoir efficiency, and irregular rainfall limits a consistent water supply |

| [29]; AU | Plan streamflow and irrigation | Supports strategic irrigation management | Alteration of flow regime, reduction in the downstream streamflow |

| [19]; AU | Biodiversity conservation | Farm dams as biodiversity hotspots | Inconsistent management for conservation |

| [20]; AU | Investigate GHG emissions, water quality | Improved biodiversity and water quality | Methane and nutrient emissions |

| [30]; AU | Assess GHG emissions in farm dams | NA | GHG emissions are underestimated globally |

| [27]; AU | Investigate water availability for irrigation, livestock, and domestic purposes | Enhances water reliability for agriculture. | Reduction in downstream flows, inequity in water availability, and cumulative environmental impacts. |

| [6]; AU | Investigate agricultural water supply for crops and livestock. | NA | Increased unreliability due to climate change; high evaporation rates |

| [25]; US | Investigate dam sediment storage and aquatic habitat restoration. | Sediment containment, preventing downstream contamination | Mercury contamination from historic mining; disruption of natural flow and sediment regime and aquatic habitats. |

| [7]; US | Assess dissolved oxygen impacts of small dams and recovery following removal. | Improved DO conditions post-removal at most sites, and enhanced stream ecology, aquatic habitat restoration. | Reduced DO within impoundments, and minimal downstream reoxygenation effects. |

| [31]; US | Guide principles for effective dam removal planning and implementation. | Long-term ecological restoration, increased public safety, and reduced liability risks. | Potential short-term ecological disruption and complex stakeholder and regulatory processes. |

| [9]; US | Understand the cumulative impacts of small reservoirs on streamflow and aquatic ecology. | Localized water supply benefits for agriculture, potential ecological advantages if properly managed. | Flow regime alteration, and river habitat connectivity disruption |

| [32]; US | Watershed management, flood control, recreation, water supply. | Provide recreational opportunities, water storage, and flood control. | Natural flow regime alterations, effects on aquatic biota. |

| [33]; US | Water supply, recreation, and milling in historical contexts. | Local water storage, potential ecological niches in altered habitats. | Fragmentation of river networks, alterations of geomorphic and ecological connectivity, siltation. |

| [24]; US | Investigate ecological restoration, support hybrid ecosystems. | Opportunities for restoration, biodiversity conservation in modified landscapes. | Difficulty in distinguishing natural from artificial ecosystems; challenges in management due to hybrid nature. |

| [34]; ET | Water harvesting, micro-dam construction | Sustainable water management and increased agricultural productivity | High dependency on rainfall, sedimentation risks |

| [28]; ET | Assess the impact of scaling sand dams for water security under climate change in Ethiopia. | Improved water access, adaptation to climate change, low cost and scalable, minimal downstream impact at a moderate scale | Potential downstream impact at large scale, sensitive to climate change, requires maintenance, cumulative costs for wide rollout. |

| [23]; ET | Evaluation of small hydropower plant feasibility | Water availability for irrigation, sustainable renewable energy | Limited flow variability may reduce generation efficiency |

| [26]; ET | Assess sedimentation impacts and reservoir management | Improved understanding of sediment management | Reservoir lifespan reduced due to sedimentation |

| [22]; IQ | Assess rainwater harvesting for agricultural water supply | Good potential for water harvesting | The distance of dams from agricultural lands makes the water supply difficult |

| [35]; IQ | Feasibility analysis for constructing small check dams | Improved water availability for irrigation, reduced runoff | High runoff losses due to evaporation |

| [36]; IQ | Evaluation and completion of main drainage projects | Efficient drainage system, improved river water quality | Salinity issues and incomplete projects |

| [37]; IQ | Design optimal small dams using the OHALM model | An optimal dam site selection may improve rainwater storage capacity | High evaporation losses of stored water |

| [3]; KE | Review of small reservoirs’ sustainability and productivity | Climate-proofing agriculture, improving livelihoods | High sedimentation, poor water quality |

| [38]; KE | Assessing the water quality of sand dams for domestic use | Water availability during drought but it requires basic purification | Microbial contamination in scoop hole water, unfit for direct consumption |

| [21]; KE | Review of sand dams as solutions for rural water security | Water scarcity mitigation, improved livelihoods | Evaporation losses, unequal benefits among communities |

4. Discussion

4.1. Site-Specificity

4.2. Cumulative Effects on River Systems

4.3. Socio-Economic Dimensions and Governance

4.4. Ecological Impacts on Fish and Riverine Habitat, and Design Measures to Mitigate the Impacts

4.5. Mudflow Management Using Small Dams

4.6. Flood Control

4.7. Research Gaps

4.8. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AU | Australia |

| CNR-IRSA | Water Research Institute of the National Research Council of Italy (Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche—Istituto di Ricerca sulle Acque) |

| CSA | Hot-summer Mediterranean climate |

| CSB | Warm-summer Mediterranean climate |

| DO | Dissolved Oxygen |

| EPA | United States Environmental Protection Agency |

| ES | Spain |

| ET | Ethiopia |

| FDA | United States Food and Drug Administration |

| GIS | Geographic Information System |

| GR | Greece |

| IQ | Iraq |

| KE | Kenya |

| MA | Morocco |

| NA | Not available |

| SWAT | Soil and Water Assessment Tool |

| TN | Tunisia |

| UN WWDR | United Nations World Water Development Report |

| US | United States |

| VOSviewer | Visualization of Similarities Viewer |

References

- Gomez-Gomez, J.d.D.; Pulido-Velazquez, D.; Collados-Lara, A.J.; Fernandez-Chacon, F. The Impact of Climate Change Scenarios on Droughts and Their Propagation in an Arid Mediterranean Basin. A Useful Approach for Planning Adaptation Strategies. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 820, 153128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN World Water Development Report 2019—Leaving No One Behind. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/wwap/wwdr/2019 (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Owusu, S.; Cofie, O.; Mul, M.; Barron, J.; Owusu, S.; Cofie, O.; Mul, M.; Barron, J. The Significance of Small Reservoirs in Sustaining Agricultural Landscapes in Dry Areas of West Africa: A Review. Water 2022, 14, 1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosaid, H.; Barakat, A.; Bouras, E.H.; Ismaili, M.; Garnaoui, M.E.; Abdelrahman, K.; Kahal, A.Y.; Mosaid, H.; Barakat, A.; Bouras, E.H.; et al. Dam Siltation in the Mediterranean Region Under Climate Change: A Case Study of Ahmed El Hansali Dam, Morocco. Water 2024, 16, 3108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leone, M.; Gentile, F.; Lo Porto, A.; Ricci, G.F.; Schürz, C.; Strauch, M.; Volk, M.; De Girolamo, A.M. Setting an Environmental Flow Regime under Climate Change in a Data-Limited Mediterranean Basin with Temporary River. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2024, 52, 101698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malerba, M.E.; Wright, N.; Macreadie, P.I. Australian Farm Dams Are Becoming Less Reliable Water Sources under Climate Change. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 829, 154360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, K.M.; Zaidel, P.A.; Roy, A.H.; Houle, K.M.; Nislow, K.H. Investigating Impacts of Small Dams and Dam Removal on Dissolved Oxygen in Streams. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0277647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itsukushima, R.; Ohtsuki, K.; Sato, T.; Kano, Y.; Takata, H.; Yoshikawa, H.; Itsukushima, R.; Ohtsuki, K.; Sato, T.; Kano, Y.; et al. Effects of Sediment Released from a Check Dam on Sediment Deposits and Fish and Macroinvertebrate Communities in a Small Stream. Water 2019, 11, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deitch, M.J.; Merenlender, A.M.; Feirer, S. Cumulative Effects of Small Reservoirs on Streamflow in Northern Coastal California Catchments. Water Resour. Manag. 2013, 27, 5101–5118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. The State of the World’s Land and Water Resources for Food and Agriculture Systems at Breaking Point; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Liu, Y.; Si, Z.; Wang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, T.; Liu, Y.; Si, Z.; Wang, L.; et al. Future Streamflow and Hydrological Drought Under CMIP6 Climate Projections. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, H.E.; Zimmermann, N.E.; McVicar, T.R.; Vergopolan, N.; Berg, A.; Wood, E.F. Present and Future Köppen-Geiger Climate Classification Maps at 1-Km Resolution. Sci. Data 2018, 5, 18024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, W.; Yang, X.; Liu, W. Sustainable Management and Regulation of Agricultural Water Resources in the Context of Global Climate Change. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badem, A.C.; Yılmaz, R.; Cesur, M.R.; Cesur, E.; Badem, A.C.; Yılmaz, R.; Cesur, M.R.; Cesur, E. Advanced Predictive Modeling for Dam Occupancy Using Historical and Meteorological Data. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebreslassie, H.; Berhane, G.; Gebreyohannes, T.; Hagos, M.; Hussien, A.; Walraevens, K.; Gebreslassie, H.; Berhane, G.; Gebreyohannes, T.; Hagos, M.; et al. Water Harvesting and Groundwater Recharge: A Comprehensive Review and Synthesis of Current Practices. Water 2025, 17, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moatti, J.-P.; Thiébault, S. The Mediterranean Region Under Climate Change; IRD: Hong Kong, China, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Avilés, A.; Niell, F.X. The Control of a Small Dam in Nutrient Inputs to a Hypertrophic Estuary in a Mediterranean Climate. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2007, 180, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felfoul, M.S.; Snane, M.H.; Albergel, J.; Mechergui, M. Relationship between Small Dam Efficiency and Gully Erodibility of the Lithologic Formations Covering Their Watershed. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2003, 62, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brainwood, M.; Burgin, S. Hotspots of Biodiversity or Homogeneous Landscapes? Farm Dams as Biodiversity Reserves in Australia. Biodivers. Conserv. 2009, 18, 3043–3052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odebiri, O.; Archbold, J.; Glen, J.; Macreadie, P.I.; Malerba, M.E. Excluding Livestock Access to Farm Dams Reduces Methane Emissions and Boosts Water Quality. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 951, 175420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, H.; Eisma, J.A.; Parker, A. Sand Dams as a Potential Solution to Rural Water Security in Drylands: Existing Research and Future Opportunities. Front. Water 2021, 3, 651954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwan, K.K.; Al-Kubaisi, M.S.A.; Al-Ansari, N.; Alwan, K.K.; Al-Kubaisi, M.S.A.; Al-Ansari, N. Validity of Existing Rain Water Harvesting Dams within Part of Western Desert, Iraq. Engineering 2019, 11, 806–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezabih, A.W. Evaluation of Small Hydropower Plant at Ribb Irrigation Dam in Amhara Regional State, Ethiopia. Environ. Syst. Res. 2021, 10, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crifasi, R.R. Reflections in a Stock Pond: Are Anthropogenically Derived Freshwater Ecosystems Natural, Artificial, or Something Else? Env. Manag. 2005, 36, 625–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, L.A. Sediment from Hydraulic Mining Detained by Englebright and Small Dams in the Yuba Basin. Geomorphology 2005, 71, 202–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moges, M.M.; Abay, D.; Engidayehu, H. Investigating Reservoir Sedimentation and Its Implications to Watershed Sediment Yield: The Case of Two Small Dams in Data-Scarce Upper Blue Nile Basin, Ethiopia. Lakes Reserv. 2018, 23, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathan, R.; Lowe, L. The Hydrologic Impacts of Farm Dams. Australas. J. Water Resour. 2012, 16, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasage, R.; Aerts, J.C.J.H.; Verburg, P.H.; Sileshi, A.S. The Role of Small Scale Sand Dams in Securing Water Supply under Climate Change in Ethiopia. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob Chang. 2015, 20, 317–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.H.; Recknagel, F.; Meyer, W.; Frizenschaf, J.; Nguyen, H.H.; Recknagel, F.; Meyer, W.; Frizenschaf, J. Analysing the Effects of Forest Cover and Irrigation Farm Dams on Streamflows of Water-Scarce Catchments in South Australia through the SWAT Model. Water 2017, 9, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, J.R.; Quayle, W.C.; Ballester, C.; Wells, N.S. Semi-Arid Irrigation Farm Dams Are a Small Source of Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Biogeochemistry 2023, 166, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonitto, C.; Riha, S.J. Planning and Implementing Small Dam Removals: Lessons Learned from Dam Removals across the Eastern United States. Sustain. Water Resour. Manag 2016, 2, 489–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedachalam, S.; Riha, S.J. Small Is Beautiful? State of the Dams and Management Implications for the Future. River. Res. Appl. 2014, 30, 1195–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fencl, J.S.; Mather, M.E.; Costigan, K.H.; Daniels, M.D. How Big of an Effect Do Small Dams Have? Using Geomorphological Footprints to Quantify Spatial Impact of Low-Head Dams and Identify Patterns of Across-Dam Variation. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0141210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fekadu, A.; Woldeyohannes, B.; Getnet, S. Potential Water Harvesting Site Identification for Micro-Dam Using Scs-Gis Approach: Case of Genfel River Catchment, Eastern Zone of Tigray, Ethiopia. J. Remote Sens. GIS 2021, 10, 255. [Google Scholar]

- Sadeq, S.N.; Mohammad, J.K. The Application of Watershed Delineation Technique and Water Harvesting Analysis to Select and Design Small Dams: A Case Study in Qara-Hanjeer Subbasin, Kirkuk-NE Iraq. Iraqi Geol. J. 2022, 55, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, M.; Al-Ansari, N.; Laue, J. Water Resources Projects in Iraq: Main Drains. J. Earth Sci. Geotech. Eng. 2019, 9, 275–281. [Google Scholar]

- Naif, R.I.; Abdulhameed, I.M. Optimal Height And Location Model (OHALM) for Rainwater Harvesting Small Dams (Iraqi Western Desert- Case Study). Iraqi J. Civ. Eng. 2020, 14, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moїse, N.; Kaluli, J.W.; Home, P.G. Evaluation of Sand-Dam Water Quality and Its Suitability for Domestic Use in Arid and Semi-Arid Environments: A Case Study of Kitui-West Sub-County, Kenya. Int. J. Water Resour. Environ. Eng. 2019, 11, 91–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dopico, E.; Arboleya, E.; Fernandez, S.; Borrell, Y.; Consuegra, S.; de Leaniz, C.G.; Lázaro, G.; Rodríguez, C.; Garcia-Vazquez, E. Water Security Determines Social Attitudes about Dams and Reservoirs in South Europe. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 6148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, A.T.P.d.; Cavalcanti, N.H.M.; Castro, B.P.L.D.; Medeiros, P.H.A. Decentralized Water Supply by Reservoir Network Reduces Power Demand for Water Distribution in a Semi-Arid Basin. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2019, 64, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Li, Q.; Lin, Y.; Zhang, J.; Xia, J.; Ni, J.; Cooke, S.J.; Best, J.; He, S.; Feng, T.; et al. River Damming Impacts on Fish Habitat and Associated Conservation Measures. Rev. Geophys. 2023, 61, e2023RG000819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doria, C.R.C.; Dutka-Gianelli, J.; Brasil de Sousa, S.T.; Chu, J.; Garlock, T.M. Understanding Impacts of Dams on the Small-Scale Fisheries of the Madeira River through the Lens of the Fisheries Performance Indicators. Mar. Policy 2021, 125, 104261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarena, F.; Comoglio, C.; Spairani, M.; Candiotto, A.; Ashraf, M.U.; Abbà, M.; Ruffino, C.; Nyqvist, D. Passage Performance of Three Small-Sized Fish Species in a Vertical Slot Fishway with and without Overhead Cover. Ecol. Eng. 2025, 219, 107713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisaniello, J.D.; Dam, T.T.; Tingey-Holyoak, J.L. International Small Dam Safety Assurance Policy Benchmarks to Avoid Dam Failure Flood Disasters in Developing Countries. J. Hydrol. 2015, 531, 1141–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmutz, S.; Sendzimir, J. (Eds.) Riverine Ecosystem Management; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villani, L.; Castelli, G.; Forzini, E.; Piemontese, L.; Lucca, E.; Bouizrou, I.; Lompi, M.; Bertoli, G.; Giuliano, A.; Chiarelli, D.D.; et al. Large Dams and Small Reservoirs: Co-Modeling Water Storage Strategies in a Mediterranean Catchment under a Changing Climate. Front. Water 2025, 7, 1673203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, W.; Yu, Z.; Lung, I.; Yarotski, J.; Elliott, J.; Tiessen, K. Assessing Effects of Small Dams on Stream Flow and Water Quality in an Agricultural Watershed. J. Hydrol. Eng. 2014, 19, 05014015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beroho, M.; Aboumaria, K.; El Hamdouni, Y.; Ouallali, A.; Jaufer, L.; Kader, S.; Hughes, P.D.; Spalevic, V.; Kuriqi, A.; Mrabet, R.; et al. A Novel SWAT-Based Framework to Integrate Climate and LULC Scenarios for Predicting Hydrology and Sediment Dynamics in the Watersheds of Mediterranean Ecosystems. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 388, 125446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminzadeh, M.; Friedrich, N.; Narayanaswamy, S.; Madani, K.; Shokri, N. Evaporation Loss From Small Agricultural Reservoirs in a Warming Climate: An Overlooked Component of Water Accounting. Earths Future 2024, 12, e2023EF004050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montaldo, N.; Sirigu, S.; Zucca, R.; Ruiu, A.; Corona, R. Hydrological Sustainability of Dam-Based Water Resources in a Mediterranean Basin Undergoing Climate Change. Hydrology 2024, 11, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminzadeh, M.; Lehmann, P.; Or, D. Evaporation Suppression and Energy Balance of Water Reservoirs Covered with Self-Assembling Floating Elements. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2018, 22, 4015–4032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yassin, A.; Ricci, G.F.; Gentile, F.; Girolamo, A.M.D. Benefits and Challenges of Small Dams in Mediterranean Climate Region: A Review. Hydrology 2026, 13, 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrology13010010

Yassin A, Ricci GF, Gentile F, Girolamo AMD. Benefits and Challenges of Small Dams in Mediterranean Climate Region: A Review. Hydrology. 2026; 13(1):10. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrology13010010

Chicago/Turabian StyleYassin, Alissar, Giovanni Francesco Ricci, Francesco Gentile, and Anna Maria De Girolamo. 2026. "Benefits and Challenges of Small Dams in Mediterranean Climate Region: A Review" Hydrology 13, no. 1: 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrology13010010

APA StyleYassin, A., Ricci, G. F., Gentile, F., & Girolamo, A. M. D. (2026). Benefits and Challenges of Small Dams in Mediterranean Climate Region: A Review. Hydrology, 13(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrology13010010