Morphological Response to Sub-Seasonal Hydrological Regulation in the Yellow River Mouth: A 1996–2023 Case Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Sources

2.3. Remote Sensing Imagery Interpretation

Tidal Bias

2.4. Planform Generalization Method for Mouth Channels

2.5. Fluctuation Analysis, Sediment Transport Coefficient, and Longitudinal Gradient

3. Results

3.1. Morphodynamic Characteristics of Mouth Channel Evolution

3.1.1. Tempo-Spatial Variation in River Mouth Channels

3.1.2. Characteristics of Mouth Channel Evolution

3.1.3. Evolution of the Natural Avulsion from 2004 to 2008

3.1.4. Evolution of the Bifurcating System Since 2014

3.2. Characteristics of the Hydrological Process into the Estuary

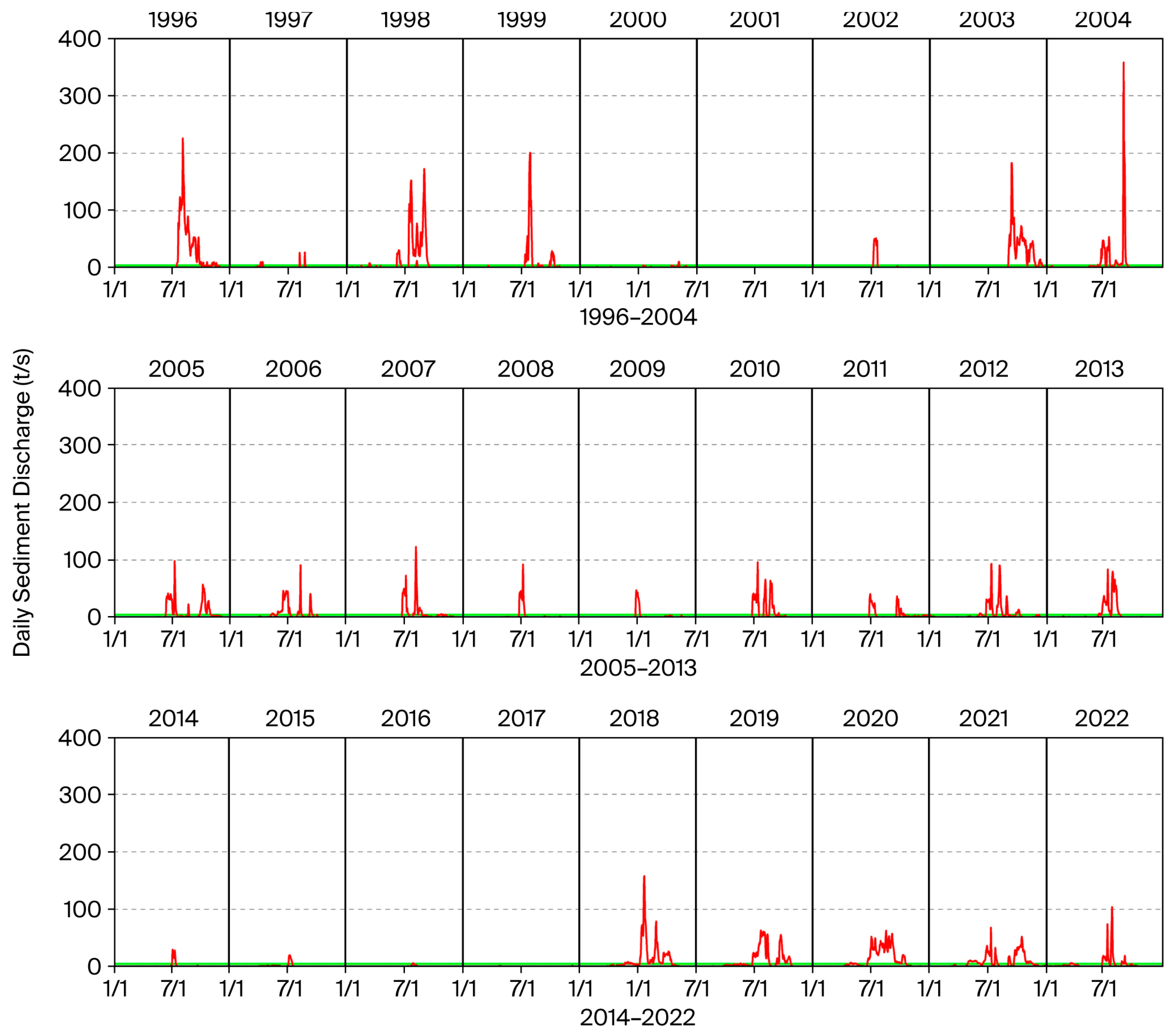

3.2.1. Variations in Water and Sediment Inputs at Yearly and Daily Scales

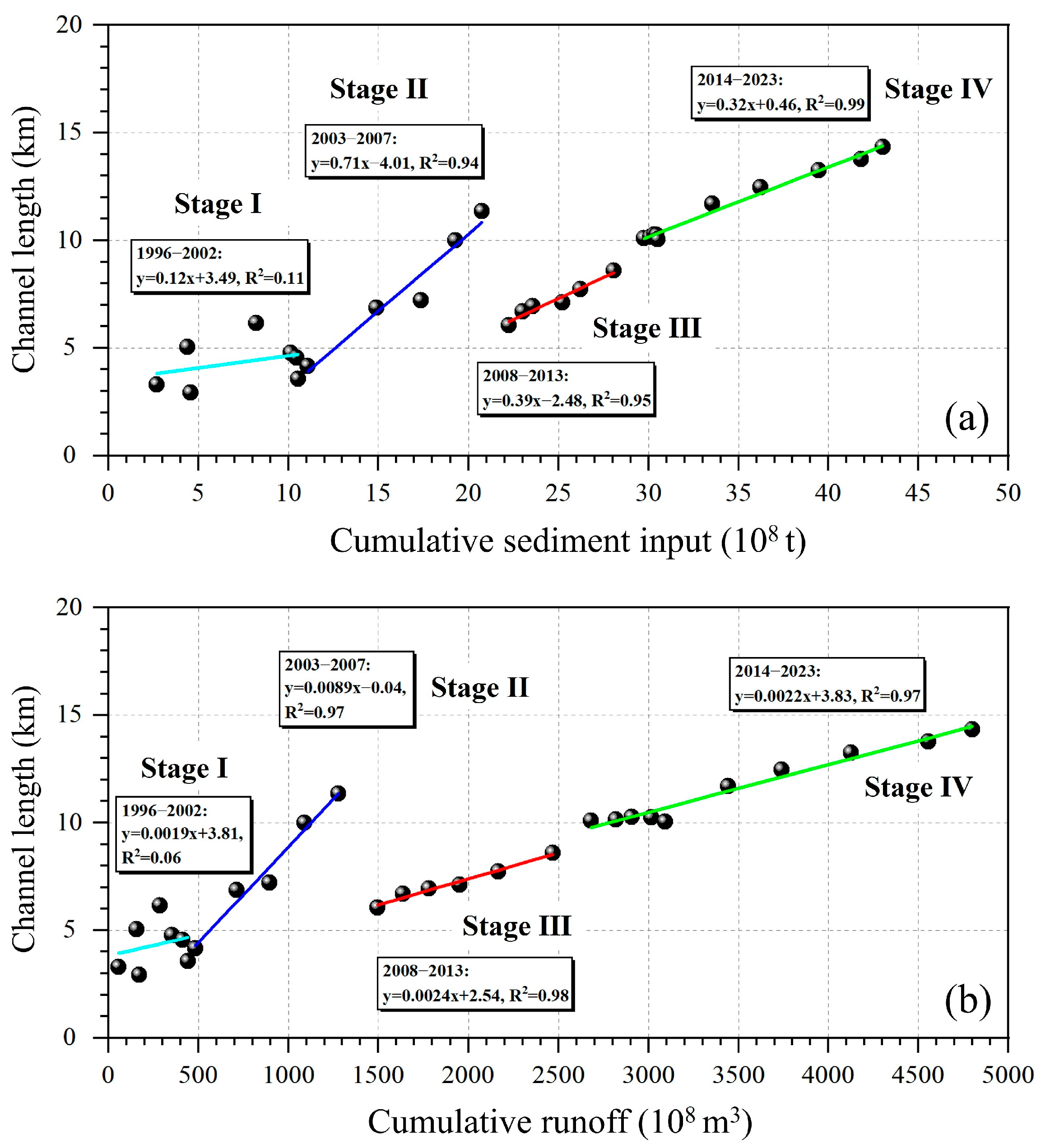

3.2.2. Relationship Between Mouth Channel Length and Water and Sediment Inputs

4. Discussion

4.1. Mechanism Underlying the Natural Avulsion

4.1.1. Avulsion Trigger

4.1.2. Effects of Flood Variability

4.2. Development of Bifurcation and Avulsion in Relation to Water and Sediment Inputs

4.3. Implications for Hydrological Regulation

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Since 1996, the mouth channels of the Yellow River have undergone a systematic geomorphic evolution, transitioning from initial progradation to a major natural avulsion, and ultimately developing into a multi-distributary system discharging simultaneously into the sea. Four distinct evolutionary stages have been identified: Stage I (1996–2002) was marked by slow channel extension. Stage II (2003–2007) was characterized by rapid channel extension; at the same time, overbank flow occurred, setting the stage for the complete avulsion in 2008. Stage III (2008–2013) experienced gradual channel adjustment and elongation along the new direction. Finally, Stage IV (2014–2023) resulted in channel bifurcation, forming a multi-channel discharging system.

- (2)

- The avulsion that occurred in 2004–2008 was initiated by extremely high sediment input over a short time in 2004, reaching 358 t/s. The significant flooding into the estuary from 2005 to 2007 also led to the transportation of large amounts of sediment over a short period, accelerating channel progradation and resulting in upstream aggradation. In contrast, the long-term hydrological regime of low sediment concentration enabled the development of a bifurcating system at the mouth of the Yellow River.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WSRS | Water-Sediment Regulation Scheme |

| YRCC | Yellow River Conservancy Commission |

| YRD | Yellow River Delta |

References

- Mikhailova, M.V. Transformation of the Ebro River Delta under the impact of intense human-induced reduction of sediment and runoff. Water Resour. 2003, 30, 370–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syvitski, J.P.M.; Kettner, A.J.; Overeem, I.; Hutton, E.W.; Hannon, M.T.; Brakenridge, G.R.; Day, J.; Vörösmarty, C.; Saito, Y.; Giosan, L.; et al. Sinking deltas due to human activities. Nat. Geosci. 2009, 2, 681–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syvitski, J.P.M.; Voeroesmarty, C.J.; Kettner, A.J.; Green, P. Impact of humans on the flux of terrestrial sediment to the global coastal ocean. Science 2005, 308, 376–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giosan, L.; Syvitski, J.; Constantinescu, S.; Day, J. Climate change: Protect the world’s deltas. Nature 2014, 516, 31–33. [Google Scholar]

- Day, J.W.; Giosan, L. Geomorphology: Survive or subside. Nat. Geosci. 2008, 1, 156–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, J.; Darby, S.E. The pace of human-induced change in large rivers: Stresses, resilience, and vulnerability to extreme events. One Earth 2020, 2, 510–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Huang, H.Q.; Nanson, G.C.; Huang, C.; Liu, G. Progradation of the Yellow (Huanghe) River delta in response to the implementation of a basin-scale water regulation program. Geomorphology 2015, 243, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Huang, H.Q.; Ran, L.; Shi, C.; Su, T. Hydrological controls on the evolution of the Yellow River Delta: An evaluation of the relationship since the Xiaolangdi Reservoir became fully operational. Hydrol. Process. 2018, 32, 3633–3649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ganti, V.; Li, C.; Wei, H. Upstream migration of avulsion sites on lowland deltas with river-mouth retreat. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2022, 577, 117270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, M.D.; Roberts, H.H. Drowning of the Mississippi Delta due to insufficient sediment supply and global sea-level rise. Nat. Geosci. 2009, 2, 488–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony, E.J.; Brunier, G.; Besset, M.; Goichot, M.; Dussouillez, P.; Nguyen, V.L. Linking rapid erosion of the Mekong River delta to human activities. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 14745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milliman, J.D.; Syvitski, J.P.M. Geomorphic/Tectonic Control of Sediment Discharge to the Ocean: The Importance of Small Mountainous Rivers. J. Geol. 1992, 100, 525–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.Y.; Liang, Z.Y. Dynamic characteristics of the Yellow River mouth. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2000, 25, 765–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.X. Response of land accretion of the Yellow River delta to global climate change and human activity. Quat. Int. 2008, 186, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Han, S.; Tan, G.; Xia, J.; Wu, B.; Wang, K.; Edmonds, D.A. Morphological adjustment of the Qingshuigou channel on the Yellow River Delta and factors controlling its avulsion. Catena 2018, 166, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganti, V.; Chu, Z.; Lamb, M.P.; Nittrouer, J.A.; Parker, G. Testing morphodynamic controls on the location and frequency of river avulsions on fans versus deltas: Huanghe (Yellow River), China. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2014, 41, 7882–7890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wu, X.; Bi, N.; Li, S.; Yuan, P.; Wang, A.; Syvitski, J.P.; Saito, Y.; Yang, Z.; Liu, S.; et al. Impacts of the dam-orientated water-sediment regulation scheme on the lower reaches and delta of the Yellow River (Huanghe): A review. Glob. Planet. Change 2017, 157, 93–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Bi, N.; Xu, J.; Nittrouer, J.A.; Yang, Z.; Saito, Y.; Wang, H. Stepwise morphological evolution of the active Yellow River (Huanghe) delta lobe (1976–2013): Dominant roles of riverine discharge and sediment grain size. Geomorphology 2017, 292, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, D.; Miao, C.; Zheng, H.; Gou, J. Dynamic evolution characteristics of the Yellow River Delta in response to estuary diversion and a water-sediment regulation scheme. J. Hydrol. 2023, 627, 130447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Bellerby, R.G.; Ji, H.; Chen, S.; Fan, Y.; Li, P. Impacts of riverine floods on morphodynamics in the Yellow River Delta. Water 2023, 15, 1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Z.X.; Sun, X.G.; Zhai, S.K.; Xu, K.H. Changing pattern of accretion/erosion of the modern Yellow River (Huanghe) subaerial delta, China: Based on remote sensing images. Mar. Geol. 2006, 227, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Bi, N.; Saito, Y.; Wang, Y.; Sun, X.; Zhang, J.; Yang, Z. Recent changes in sediment delivery by the Huanghe (Yellow River) to the sea: Causes and environmental implications in its estuary. J. Hydrol. 2010, 391, 302–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, N.; Wang, H.; Yang, Z. Recent changes in the erosion–accretion patterns of the active Huanghe (Yellow River) delta lobe caused by human activities. Cont. Shelf Res. 2014, 90, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, H.; Pan, S.; Chen, S. Impact of river discharge on hydrodynamics and sedimentary processes at Yellow River Delta. Mar. Geol. 2020, 425, 106210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Pan, S.; Chen, S. Recent morphological changes of the Yellow River (Huanghe) submerged delta: Causes and environmental implications. Geomorphology 2017, 293, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Chen, S.; Ji, H.; Fan, Y.; Li, P. The modern Yellow River Delta in transition: Causes and implications. Mar. Geol. 2021, 436, 106476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Zhang, S.; Du, X.; Wang, G.; Yu, S.; Dou, S.; Chen, S.; Ji, H.; Li, P.; Liu, F. The effects of flow pulses on river plumes in the Yellow River Estuary, in spring. J. Hydroinformatics 2023, 25, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Fan, Y.; Wang, H.; Bi, N.; Yang, Z.; Xu, C. Geomorphological responses of the lower river channel and delta to interruption of reservoir regulation in the Yellow River, 2015–2017. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2021, 66, 3059–3070, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, H.; Chen, S.; Pan, S.; Xu, C.; Tian, Y.; Li, P.; Liu, Q.; Chen, L. Fluvial sediment source to sink transfer at the Yellow River Delta: Quantifications, causes, and environmental impacts. J. Hydrol. 2022, 608, 127622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yang, Z.; Saito, Y.; Liu, J.P.; Sun, X.; Wang, Y. Stepwise decreases of the Huanghe (Yellow River) sediment load (1950–2005): Impacts of climate change and human activities. Glob. Planet. Change 2007, 57, 331–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yang, Z.; Saito, Y.; Liu, J.P.; Sun, X. Interannual and seasonal variation of the Huanghe (Yellow River) water discharge over the past 50 years: Connections to impacts from ENSO events and dams. Glob. Planet. Change 2006, 50, 212–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Chen, S.; Zhao, B.; Yu, S.; Ji, H.; Jiang, C. Monitoring tidal flat dynamics affected by human activities along an eroded coast in the Yellow River Delta, China. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2018, 190, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Chen, S. Response of delta sedimentary system to variation of water and sediment in the Yellow River over past six decades. J. Geogr. Sci. 2010, 20, 613–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Wang, H.; Bi, N.; Nittrouer, J.A.; Xu, J.; Cong, S.; Carlson, B.; Lu, T.; Li, Z. Evolution of a tide-dominated abandoned channel: A case of the abandoned Qingshuigou course, Yellow River. Mar. Geol. 2020, 422, 106116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Wang, H.; Saito, Y.; Syvitski, J.; Bi, N.; Yang, Z.; Xu, J.; Guan, W. Boosting riverine sediment by artificial flood in the Yellow River and the implication for delta restoration. Mar. Geol. 2022, 448, 106816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Rice, S.; Tan, G.; Wang, K.; Zheng, S. Geomorphic evolution of the Qingshuigou channel of the Yellow River Delta in response to changing water and sediment regimes and human interventions. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2020, 45, 2350–2364. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H. Modification of normalised difference water index (NDWI) to enhance open water features in remotely sensed imagery. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2006, 27, 3025–3033. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker, C.J. Red and photographic infrared linear combinations for monitoring vegetation. Remote Sens. Environ. 1979, 8, 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Hao, D.; Huete, A.; Dechant, B.; Berry, J.; Chen, J.M.; Joiner, J.; Frankenberg, C.; Bond-Lamberty, B.; Ryu, Y.; et al. Optical vegetation indices for monitoring terrestrial ecosystems globally. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2022, 3, 477–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.S.; Zhao, Y.Y.; Zhao, S.L. Geology of Bohai Sea; Science Press: Beijing, China, 1985; pp. 61–66. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Slingerland, R.; Smith, N.D. River avulsions and their deposits. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2004, 32, 257–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohrig, D.; Heller, P.L.; Paola, C.; Lyons, W.J. Interpreting avulsion process from ancient alluvial sequences: Guadalope-Matarranya system (northern Spain) and Wasatch Formation (western Colorado). Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 2000, 112, 1787–1803. [Google Scholar]

- Jerolmack, D.J. Conceptual framework for assessing the response of delta channel networks to Holocene sea level rise. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2009, 28, 1786–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reitz, M.D.; Jerolmack, D.J. Experimental alluvial fan evolution: Channel dynamics, slope controls, and shoreline growth. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 2012, 117, F02021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dijk, M.; Kleinhans, M.G.; Postma, G.; Kraal, E. Contrasting morphodynamics in alluvial fans and fan deltas: Effect of the downstream boundary. Sedimentology 2012, 59, 2125–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmonds, D.A.; Hoyal, D.C.; Sheets, B.A.; Slingerland, R.L. Predicting delta avulsions: Implications for coastal wetland restoration. Geology 2009, 37, 759–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajek, E.A.; Heller, P.L.; Schur, E.L. Field test of autogenic control on alluvial stratigraphy (Ferris Formation, Upper Cretaceous-Paleogene, Wyoming). Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 2012, 124, 1898–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, G.; Paola, C.; Whipple, K.X.; Mohrig, D. Alluvial fans formed by channelized fluvial and sheet flow. I: Theory. J. Hydraul. Eng. 1998, 124, 985–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadwick, A.J.; Lamb, M.P.; Moodie, A.J.; Parker, G.; Nittrouer, J.A. Origin of a preferential avulsion node on lowland river deltas. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2019, 46, 4267–4277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatanantavet, P.; Lamb, M.P.; Nittrouer, J.A. Backwater controls of avulsion location on deltas. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2012, 39, L01402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganti, V.; Chadwick, A.J.; Hassenruck-Gudipati, H.J.; Fuller, B.M.; Lamb, M.P. Experimental river delta size set by multiple floods and backwater hydrodynamics. Sci. Adv. 2016, 2, e1501768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Edmonds, D.A.; Wu, B.; Han, S. Backwater controls on the evolution and avulsion of the Qingshuigou channel on the Yellow River Delta. Geomorphology 2019, 333, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Wang, G.; Xia, J.; Fu, X.; Zhang, Y. Response of bankfull discharge to discharge and sediment load in the Lower Yellow River. Geomorphology 2008, 100, 366–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.; Liang, G.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, G.; Zhang, L.; Cheng, L. Range survey of deposition in the lower Yellow River. Int. J. Sediment Res. 2002, 17, 91–101. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Fu, B.; Piao, S.; Lü, Y.; Ciais, P.; Feng, X.; Wang, Y. Reduced sediment transport in the Yellow River due to anthropogenic changes. Nat. Geosci. 2016, 9, 38–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Haas, T.; van den Berg, W.; Braat, L.; Kleinhans, M.G. Autogenic avulsion, channelization and backfilling dynamics of debris-flow fans. Sedimentology 2016, 63, 1596–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyal, D.; Sheets, B.A. Morphodynamic evolution of experimental cohesive deltas. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 2009, 114, F02009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Haas, T.; Densmore, A.L.; den Hond, T.; Cox, N.J. Fan-surface evidence for debris-flow avulsion controls and probabilities, Saline Valley, California. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 2019, 124, 1118–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Zhang, X.L.; Wu, B.S.; Hou, S.Z. Asynchronous movement of water-sediment and the sediment delivery ratio of the Xiaolangdi Reservoir. J. Sediment Res. 2021, 46, 1–8, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Paola, C.; Twilley, R.R.; Edmonds, D.A.; Kim, W.; Mohrig, D.; Parker, G.; Viparelli, E.; Voller, V.R. Natural processes in delta restoration: Application to the Mississippi Delta. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 2011, 3, 67–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syvitski, J.P.M.; Saito, Y. Morphodynamics of deltas under the influence of humans. Glob. Planet. Change 2007, 57, 261–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmonds, D.A.; Slingerland, R.L. Significant effect of sediment cohesion on delta morphology. Nat. Geosci. 2010, 3, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nittrouer, J.A.; Viparelli, E. Sand as a stable and sustainable resource for nourishing the Mississippi River delta. Nat. Geosci. 2014, 7, 350–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Saito, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Bi, N.; Sun, X.; Yang, Z. Recent changes of sediment flux to the western Pacific Ocean from major rivers in East and Southeast Asia. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2011, 108, 80–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Stage | Period | Channel Length (km) | Average Length (km) | Extension Rate (km/Year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage I | 1996 | 3.31 | 4.02 | 0.12 |

| 1997–1998 | 3.99 | |||

| 1999–2002 | 4.77 | |||

| Stage II | 2003–2004 | 5.52 | 7.52 | 1.79 |

| 2005–2007 | 9.52 | |||

| Stage III | 2008–2010 | 6.57 | 7.2 | 0.68 |

| 2011–2013 | 7.82 | |||

| Stage IV | 2014–2018 | 10.16 | 12.23 | 0.47 |

| 2019–2021 | 12.47 | |||

| 2022–2023 | 14.06 |

| ξ > 0.015 | ξ | ξ < 0.01 |

|---|---|---|

| 1996–2004 | 2005–2010 | 2011–2022 |

| Phase | Type * | Patterns of Flood Events | Sediment Load (108 t) | Runoff (108 m3) | Sediment Concentration (kg/m3) | Sediment Transport Coefficient | Mouth Channel Growth Rate (km/Year) | Mouth Channel Evolution Stage | R2 of CS, CR ** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1997–2002 | Low | Interrupted | 1.12 | 55.01 | 15.52 | 0.089 | −0.15 | Stage I | 0.11, 0.06 |

| 2003–2007 | High | Multi | 2.23 | 198.8 | 11.27 | 0.018 | 1.79 | Stage II | 0.94, 0.97 |

| 2008–2009 | Low | Single | 0.67 | 139.25 | 4.76 | 0.011 | 0.45 | Stage III | 0.95, 0.98 |

| 2010–2013 | High | Multi | 1.54 | 224.14 | 6.86 | 0.010 | 0.79 | ||

| 2014–2017 | Low | Single | 0.2 | 104.83 | 1.79 | 0.005 | −0.01 | Stage IV | 0.99, 0.97 |

| 2018–2022 | High | Multi | 2.5 | 341.53 | 7.32 | 0.007 | 0.86 |

| Year | Flood Duration (Months) | Number of Floods | Flood Peak Discharge (m3/s) | Avulsing Process |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | 3.5 | 4 | 2900 | Overbank flow (Figure 5a) |

| 2005 | 5 | 5 | 2900 | Overbank flow (Figure 5b,c) |

| 2006 | 4.5 | 3 | 3600 | Widespread gully flow (Figure 5d–f) |

| 2007 | 2.5 | 3 | 3800 | New branch formation (Figure 5h,i) |

| 2008 | 0.7 | 1 | 4000 | New channel selection (Figure 5k,l) |

| 2009 | 0.6 | 1 | 3700 | Channelized (Figure 5n,o) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhu, J.; Huang, H.Q.; Yu, G.-A.; Hou, W.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, X. Morphological Response to Sub-Seasonal Hydrological Regulation in the Yellow River Mouth: A 1996–2023 Case Study. Hydrology 2025, 12, 335. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrology12120335

Zhu J, Huang HQ, Yu G-A, Hou W, Zhao X, Zhang X. Morphological Response to Sub-Seasonal Hydrological Regulation in the Yellow River Mouth: A 1996–2023 Case Study. Hydrology. 2025; 12(12):335. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrology12120335

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhu, Jingjing, He Qing Huang, Guo-An Yu, Weipeng Hou, Xiao Zhao, and Xueqin Zhang. 2025. "Morphological Response to Sub-Seasonal Hydrological Regulation in the Yellow River Mouth: A 1996–2023 Case Study" Hydrology 12, no. 12: 335. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrology12120335

APA StyleZhu, J., Huang, H. Q., Yu, G.-A., Hou, W., Zhao, X., & Zhang, X. (2025). Morphological Response to Sub-Seasonal Hydrological Regulation in the Yellow River Mouth: A 1996–2023 Case Study. Hydrology, 12(12), 335. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrology12120335