A Principles-Based Approach for Enabling Multi-Stakeholder Collaboration: Addressing the Elusive Quest for Sustainable Development Partnership Standards

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Why Partnership Context Matters

3. Our Methodology

4. Terminology and Standards

5. The Historical Context for Partnership Standards

5.1. Legitimization of Non-State Actors in Global Governance (1990–2000)

5.2. Strengthening Partnership Governance and Accountability (2000–2015)

5.3. Meta-Governance for SDG Partnerships (2015 to Date)

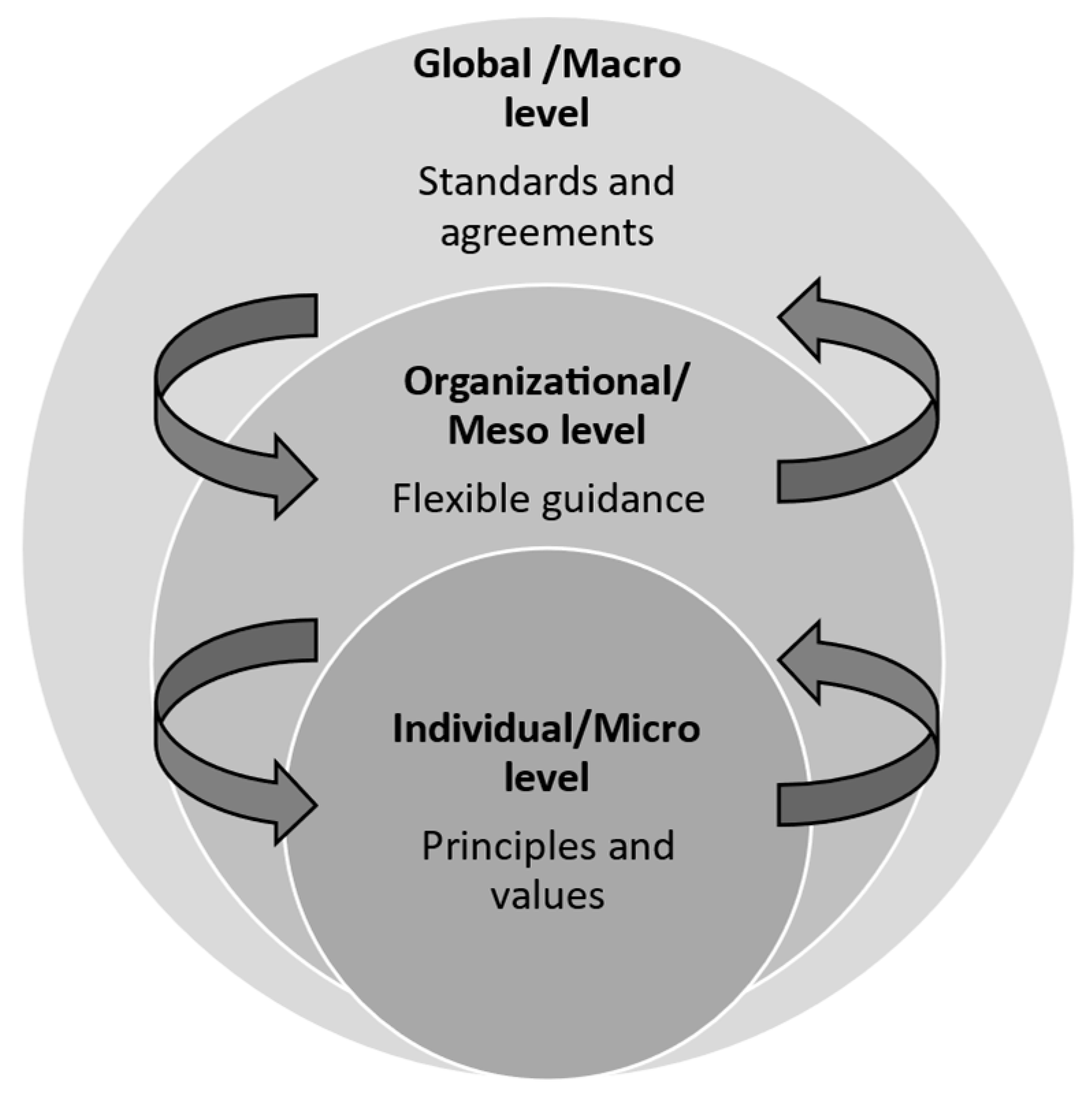

6. Beyond Standards: A Principles-Based Partnership Approach

- Connectedness: The promotion of linkages across different disciplines, sectors, levels of operation, sustainable development pillars and themes by adopting a systems perspective that incorporates these interconnections.

- Engagement: The active involvement of all partners in different phases and processes of partnering as well as those stakeholders who influence or may be influenced by a partnership arrangement.

- Fairness: Ensuring that no partner dominates, that all contributions are valued equitably and that all partners gain something positive from the relationship.

- Respect: Acceptance of difference and reinforcement of the importance of embracing diverse viewpoints.

- Transparency: Openness and clarity around how partners work together.

- Bravery: The courage to seek meaningful change by inquiring, testing, learning and sharing from different partnership experiences.

- Transformation: Dedication to the idea of consolidating both partnership results and processes so that they promote change as they become embedded within partner organizations and institutional and policy frameworks.

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ECCP | European Code of Conduct on Partnership |

| ISO | International Organization for Standardization |

| MSP | Multi-stakeholder partnership |

| PBA | Partnership Brokers Association |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goal |

| UN | United Nations |

| UNEP | United Nations Environment Program |

| UNFSS | United Nations Forum on Sustainability Standards |

| VSS | Voluntary Sustainability Standard(s) |

References

- Stott, L.; Murphy, D.F. An inclusive approach to partnerships for the SDGs: Using a relationship lens to explore the potential for transformational collaboration. Special Issue: Partnerships for the SDGs. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; Resolution 70/1 Adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on 25 September 2015; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/A_RES_70_1_E.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Beisheim, M.; Simon, N. Meta-Governance of Partnerships for Sustainable Development: Perspectives on How the UN Could Improve Partnerships‘ Governance Services in Areas of Limited Statehood; SFB-Governance Working Paper Series, 68; Collaborative Research Center (SFB): Berlin, Germany, 2015; Available online: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-449883 (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Sondermann, E.; Ulbert, C. Transformation through ‘meaningful’ partnership? SDG 17 as metagovernance norm and its global health implementation. Politics Gov. 2021, 9, 152–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poncelet, E.C. “A kiss here and a kiss there”: Conflict and collaboration in environmental partnerships. Environ. Manag. 2001, 27, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, D.F.; Stott, L. Partnerships for the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Sustainability 2021, 13, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Pact for the Future, Global Digital Compact and Declaration on Future Generations; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2024; Available online: https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/sotf-pact_for_the_future_adopted.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Desai, B.H. Pact for the Future and Future of the Planet: A Stocktaking. Environ. Policy Law 2025, 54, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon-Woods, M. The problem of context in quality improvement. In Perspectives on Context; Health Foundation, Ed.; Health Foundation: London, UK, 2014; Available online: https://www.health.org.uk/sites/default/files/PerspectivesOnContext_fullversion.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Bateson, N. Combining; Triarchy Press: Axminster, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Pattberg, P.; Widerberg, O. Transnational multistakeholder partnerships for sustainable development: Conditions for success. Ambio 2016, 45, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beisheim, M.; Ellersiek, A.; Goltermann, L.; Kiamba, P. Meta-Governance of Partnerships for Sustainable Development: Actors’ Perspectives from Kenya. Public Adm. Dev. 2017, 38, 105–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellersiek, A. Donors and Funders’ Meta-Governance of Multi-Stakeholder Partnerships; SWP Working Paper, 02; Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik (SWP): Berlin, Germany, 2018; Available online: https://www.swp-berlin.org/fileadmin/contents/products/arbeitspapiere/Ellersiek_FG08_Working_Paper_2018_01.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Bateson, G. Steps to an Ecology of Mind; Jason Aronson Inc.: London, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Bateson, N. Small Arcs of Large Circles: Framing Through Other Patterns; Triarchy Press: Axminster, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lubell, M. Collaborative partnerships in complex institutional systems. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2015, 12, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stott, L. Partnership and Transformation: The Promise of Multi-Stakeholder Collaboration in Context; Routledge: New York, NY, USA; Taylor and Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stott, L.; Scoppetta, A. Changing the focus: Towards a new evidence base for SDG 17. In The Elgar Companion to Data and Indicators for the Sustainable Development Goals, Elgar Companions to the Sustainable Development Goals Series; Umbach, G., Tkalec, I., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2025; in press. [Google Scholar]

- van Norren, D.; Beehner, C. Sustainability leadership, UNESCO competencies for SDGs, and diverse leadership models. Int. J. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 10, 24–49. Available online: https://isdsnet.com/ijds-v10n1-03.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Brouwer, H.; Woodhill, J.; Hemmati, M.; Verhoosel, K.; van Vugt, S. The MSP Guide, How to Design and Facilitate Multi-Stakeholder Partnerships, 3rd ed.; Wageningen University and Research, WCDI: Wageningen, The Netherlands; Practical Action Publishing: Rugby, UK, 2019; Available online: https://edepot.wur.nl/543151 (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Jacklin-Jarvis, C. Collaborating across sector boundaries: A story of tensions and dilemmas. Volunt. Sect. Rev. 2015, 6, 285–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The International Standards Organization (ISO). Consumers and Standards: Partnership for a Better World. Available online: https://www.iso.org/sites/ConsumersStandards/1_standards.html#section1_1 (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Glavič, P. Feature Papers to Celebrate the Inaugural Issue of Standards. Standards 2023, 3, 133–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellersiek, A.; Beisheim, M. Partnerships for the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development: Transformative, Inclusive and Accountable? SWP Research Paper 14/2017; Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik (SWP): Berlin, Germany, 2017; Available online: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-55740-7 (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Beisheim, M.; Simon, N. Multi-Stakeholder Partnerships for Implementing the 2030 Agenda: Improving accountability and transparency. In Proceedings of the Analytical Paper for the 2016 ECOSOC Partnership Forum, New York, NY, USA, 18 March 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beisheim, M.; Simon, N. Multistakeholder Partnerships for the SDGs: Actors’ Views on UN Metagovernance. Glob. Gov. A Rev. Multilater. Int. Organ. 2018, 24, 497–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, D.; Fortier, F.; Boucher, J.F.; Riffon, O.; Villeneuve, C. Sustainable development goal interactions: An analysis based on the five pillars of the 2030 agenda. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 28, 1584–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horan, D. A new approach to partnerships for SDG transformations. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Report of the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development; Annex 1, Rio Declaration on Environment and Development, General Assembly, A/CONF.151/26; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 1993; Volume I, Available online: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/A_CONF.151_26_Vol.I_Declaration.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- United Nations. In Proceedings of the United Nations Conference on Environment & Development, Agenda 21, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 3–14 June 1992. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/Agenda21.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Waddock, S. Building a new institutional infrastructure for corporate responsibility. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2008, 22, 87–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.; Murphy, D.F. Learning from Each Other: UK Global Businesses, SMEs, CSR and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Sustainability 2023, 15, 4151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, K.; Karliner, J. Earthsummit.biz: The Corporate Takeover of Sustainable Development; Food First Books & Corp Watch: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Richter, J. Codes in Context: TNC Regulation in an Era of Dialogues and Partnerships. In Corner House Briefing Paper; Zed Books: London, UK, 2002; No. 26; Available online: https://www.thecornerhouse.org.uk/resource/codes-context (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Utting, P.; Zammit, A. Beyond pragmatism: Appraising UN-business partnerships. In Market, Business and Regulation Programme Paper, 1; UNRISD: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006; Available online: https://cdn.unrisd.org/assets/library/papers/pdf-files/uttzam.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Utting, P.; Zammit, A. United Nations-business partnerships: Good intentions and contradictory agendas. J. Bus. Ethic 2009, 90, 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, J. Public-private Partnerships for Health: A trend with no alternatives? Development 2004, 47, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, D.F.; Bendell, J. In the Company of Partners: Business, Environmental Groups and Sustainable Development Post-Rio; The Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Livesey, S.M.; Kearins, K. Transparent and caring corporations? A study of sustainability reports by The Body Shop and Royal Dutch/Shell. Organ. Environ. 2002, 15, 233–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Reporting Initiative (GRI). Available online: https://www.globalreporting.org/ (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- United Nations Global Compact. Available online: https://unglobalcompact.org/ (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Ethical Trading Initiative. Available online: https://www.ethicaltrade.org/about-eti/who-we-are/etis-origins (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Fair Labor Association. Available online: https://www.fairlabor.org/ (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Fairtrade. Available online: https://www.fairtrade.net/en.html (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Rainforest Alliance. Available online: https://www.rainforest-alliance.org/ (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Forest Stewardship Council. Available online: https://fsc.org/en (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- United Nations. Guidelines, Cooperation Between the United Nations and the Business Community; United Nations Secretary General; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 17 July 2000; Available online: https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/migration/lb/g_c_business_communities.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- CARE USA. Partnership Manual; CARE: Atlanta, GA, USA, 1997; Available online: https://cercle.lu/download/partenariats/ccccare_partnership_manual25-3.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Austin, J.E.; Reavis, C. Starbucks and Conservation International. In Harvard Business School Case 303-055; Harvard Business School: Boston, MA, USA, 2002; Available online: https://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Pages/item.aspx?num=29323 (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Austin, J.E. Strategic Collaboration Between Nonprofits and Businesses. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2000, 29 (Suppl. S1), 69–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, J. Building Partnerships, Cooperation Between the UN System and the Private Sector; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. United Nations Millennium Declaration; Resolution adopted by the General Assembly, A/RES/55/2; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 18 September 2000; Available online: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/A_RES_55_2.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- United Nations Millennium Development Goals. Available online: https://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/ (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Witte, J.M.; Streck, C.; Benner, T. (Eds.) Progress or Peril? Partnerships in Global Environmental Governance, The Post-Johannesburg Agenda; Global Public Policy Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Zadek, S. Civil Governance and Partnerships. In Partnership Matters, Current Issues in Cross-Sector Collaboration; The Partnering Initiative: London, UK, 2004; Issue 2; Available online: https://archive.thepartneringinitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/PartnershipMatters2.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- United Nations. Towards Global Partnerships. In Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly on 24 January 2002, Fifty-Sixth Session, Agenda item 39; United Nations: New York, NY, USA; Available online: https://docs.un.org/en/A/RES/56/76 (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Principles of Partnership. A Statement of Commitment Endorsed by the Global Humanitarian Platform. Available online: https://www.icvanetwork.org/uploads/2021/09/Principles-of-Parnership.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Voluntary Principles on Security and Human Rights. Available online: https://www.voluntaryprinciples.org/ (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- GRI, Vision, Mission and History. Available online: https://www.globalreporting.org/about-gri/mission-history/ (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- 25 Years of the UN Global Compact: A Legacy of Impact and a Call for Bold Action. Available online: https://unglobalcompact.org/compactjournal/25-years-un-global-compact-legacy-impact-and-call-bold-action (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Kosolapova, E.; Verma, R.; Turley, L.; Wilkings, A. IISD’s State of Sustainability Initiatives Review: Standards and the Sustainable Development Goals: Leveraging Sustainability Standards for Reporting on SDG Progress; International Institute for Sustainable Development: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2023; Available online: https://www.iisd.org/system/files/2023-05/ssi-review-standards-sustainable-development-goals-sdgs.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- United Nations Forum on Sustainability Standards (UNFSS). Voluntary Sustainability Standards: Today’s Landscape of Issues and Initiatives to Achieve Public Policy Objectives (Part I: Issues). In 1st Flagship Report of the United Nations Forum on Sustainability Standards; UNFSS: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012; Available online: https://unfss.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/unfss-report-issues-1_draft_lores.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- van der Ven, H. Effects of stakeholder input on voluntary sustainability standards. Glob. Environ. Change 2022, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AccountAbility. 30 Years of Setting the Standard for Sustainability. Available online: https://www.accountability.org/standards (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- AccountAbility. AA1000 AccountAbility Principles. Available online: https://www.accountability.org/standards/aa1000-accountability-principles (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- European Union (EU). Commission Delegated Regulation (EU), No 240/2014 of 7 January 2014 on the European Code of Conduct on Partnership in the Framework of the European Structural and Investment Funds; EU: Brussels, Belgium, 2014; Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32014R0240 (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Tennyson, R. The Partnering Toolbook, 4th ed.; The Partnering Initiative: Oxford, UK, 2011; Available online: https://archive.thepartneringinitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Partnering-Toolbook-en-20113.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Partnership Brokers Association (PBA). Available online: https://www.partnershipbrokers.org/ (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Mundy, J. Embedding ethical and principled partnering approaches. In Shaping Sustainable Change: The role of Partnership Brokering in Optimising Collaborative Action; Stott, L., Ed.; Greenleaf Publishing, Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fransen, L.; Kolk, A. Global rule-setting for business: A critical analysis of multi-stakeholder standards. Organization 2007, 14, 667–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Sustainable Development. SDG Actions Platform. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/partnerships (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Stott, L.; Scoppetta, A. Partnerships for the Goals: Beyond SDG 17. In Revista Diecisiete: Investigación Interdisciplinar Para Los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible (Journal Seventeen: Interdisciplinary Research for the SDGs); Fundación Acción contra el Hambre: Madrid, Spain, 2020; Volume 2, pp. 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Sustainable Development Group (UNSDG). Common Minimum Standards for Multi-Stakeholder Engagement in the UN Development Assistance Framework; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2020; Available online: https://unsdg.un.org/resources/common-minimum-standards-multi-stakeholder-engagement-undaf (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Chakkol, M.; Selviaridis, K.; Finne, M. The governance of collaboration in complex projects. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2018, 38, 997–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLennan, N. Collaborative Principles for Better Supply Chain Practice: Value Creation up, down and Across Supply Chains; Kindle Edition; Kogan Page: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- No. 44001:2017; Collaborative Business Relationship Management Systems—Requirements and Framework. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/72798.html (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Marx, A.; Depoorter, C. Achieving the Global 2030 Agenda: What Role for Voluntary Sustainability Standards? In Transitioning to Strong Partnerships for the Sustainable Development Goals; von Schnurbein, G., Ed.; MDPI: Basel, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, J.; Vegelin, C. Sustainable development goals and inclusive development. Int. Environ. Agreem. Politics Law Econ. 2016, 16, 433–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meuleman, L.; Niestroy, I. Common but differentiated governance: A metagovernance approach to make the SDGs work. Sustainability 2015, 7, 12295–12321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, D.; Utting, P.; Mukherjee-Reed, A. Business Regulation and Non-State Actors: Whose Standards? Whose Development? Routledge: London, UK; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stott, L. Listening to the Critics: Can we Learn from Arguments Against Partnerships with Business? Research Paper; Building Partnerships for Development (BPD): London, UK, 2005; Available online: http://www.bpdws.org/web/d/doc_46.pdf?statsHandlerDone=1 (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Steets, J. Accountability in Public Policy Partnerships; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stott, L. Review of the European Code of Conduct on Partnership (ECCP); Technical Dossier No.7; DG Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion, EU: Brussels, Belgium, 2018; Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2767/418803 (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Rasche, A.; Waddock, S.; McIntosh, M. The United Nations Global Compact: Retrospect and prospect. Bus. Soc. 2012, 52, 6–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanberry, J. I am, I can, I ought, I will: Responsible leadership and the failures of ethics. Int. J. Ethics Syst. 2025, 41, 705–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Paris Agreement; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/english_paris_agreement.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- United Nations. Addis Ababa Action Agenda on Financing for Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/index.php?page=view&type=400&nr=2051&menu=35 (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- ILO. A Guide to Multi-Stakeholder Partnerships; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://www.ilo.org/resource/training-material/guide-multi-stakeholder-partnerships (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- The Intersector Project. The Intersector Toolkit: Tools for Cross-Sector Collaboration; The Intersector Project: Washington, DC, USA; New York, NY, USA, 2017; Available online: https://intersector.com/toolkit/ (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Mundy, J.; Tennyson, R. Brokering Better Partnerships; Partnership Brokers Association (PBA): London, UK, 2019; Available online: https://partnershipbrokers.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/Brokering-Better-Partnerships-Handbook.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- PBA. The Remote Partnering Workbook; Partnership Brokers Association (PBA): London, UK, 2018; Available online: https://www.remotepartnering.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Remote-Partnering-Work-Book_Feb-2018.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Reid, S. The Partnership Culture Navigator: Organisational Cultures and Cross-Sector Partnership; The Partnering Initiative: Oxford, UK, 2016; Available online: https://thepartneringinitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Partnership-Culture-Navigator-v1.0.3.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Stibbe, D.T.; Reid, S.; Gilbert, J. Maximising the Impact of Partnerships for the SDGs; The Partnering Initiative and UN DESA: Oxford UK; New York, NY, USA, 2019; Available online: https://thepartneringinitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Maximising-partnership-value-for-the-SDGs.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Stibbe, D.; Prescott, D. The SDG Partnership Guidebook: A Practical Guide to Building High-Impact Multi-Stakeholder Partnerships for the Sustainable Development Goals; The Partnering Initiative: Oxford, UK; UN DESA: New York, NY, USA, 2020; Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/publications/sdg-partnership-guidebook-24566 (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Stott, L. Guidebook—How ESF Managing Authorities and Intermediate Bodies Support Partnership, Revised ed.; DG Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion, European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019; Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2767/946587 (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- United Nations. Guidelines on a Principle-Based Approach to the Cooperation Between the United Nations and the Business Sector; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: https://www.un.org/en/ethics/assets/pdfs/Guidelines-on-Cooperation-with-the-Business-Sector.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Brouwer, H.; Hemmati, M.; Woodhill, J. Seven principles for effective and healthy multi-stakeholder partnerships. Great Insights 2019, 8, 9–11. Available online: https://ecdpm.org/great-insights/civil-society-business-same-direction/seven-principles-effective-multi-stakeholder-partnerships/ (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- The MSP Charter Project. The MSP Charter, Principles of Multi-Stakeholder Partnerships for Sustainable Development. MSP Institute, Berlin, Germany & Tellus Institute: Cambridge, MA, USA, December 2018; Available online: https://msp-institute.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/MSP-Charter-2018.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Ball, N.; Gibson, M. Partnerships with Principles: Putting Relationships at the Heart of Public Contracts for Better Social Outcomes; Government Outcomes Lab, Blavatnik School of Government, University of Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2022; Available online: https://golab.bsg.ox.ac.uk/documents/Partnerships_with_principles_final_web.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Hoekstra, F.; Mrklas, K.J.; Khan, M.; McKay, R.C.; Vis-Dunbar, M.; Sibley, K.M.; Nguyen, T.; Graham, I.D.; SCI Guiding Principles Consensus Panel; Gainforth, H.L. A review of reviews on principles, strategies, outcomes and impacts of research partnerships approaches: A first step in synthesising the research partnership literature. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2020, 18, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, G.; Fewer, T.J.; Lazzarini, S.; McGahan, A.M.; Puranam, P. Partnering for grand challenges: A review of organizational design considerations in public–private collaborations. J. Manag. 2024, 50, 10–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zero Carbon Cumbria. Available online: https://zerocarboncumbria.co.uk/action/partnership-registration-form/ (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Moreno-Serna, J.; Sánchez-Chaparro, T.; Stott, L.; Mazorra, J.; Carrasco-Gallego, R.; Mataix, C. Feedback Loops and Facilitation: Catalyzing Transformational Multi-Stakeholder Refugee Response Partnerships. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzucato, M. Principles for an Inclusive and Sustainable Global Economy: A Discussion Paper for the G20; University College London (UCL) Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose: London, UK, 2025; Available online: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/bartlett/ucl-institute-innovation-and-public-purpose/principles-inclusive-and-sustainable-global-economy-discussion-paper-g20 (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Kenter, J.O.; Martino, S.; Buckton, S.J.; Waddock, S.; Agarwal, B.; Anger-Kraavi, A.; Costanza, R.; Hejnowicz, A.P.; Jones, P.; Lafayette, J.O.; et al. Ten principles for transforming economics in a time of global crises. Nat. Sustain. 2025, 8, 837–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Partnership may be understood as follows: |

|---|

| An entity with a clear governance structure and procedures for working in collaboration, and organizational alignment around a common goal |

| A process of working together that encourages dialogue and consultation, and the participation of different stakeholders |

| A relationship based on values such as solidarity, empathy and reciprocity in which those involved benefit mutually from their connection |

| Term | Definition | Level of Formality |

|---|---|---|

| Principle | A fundamental belief or guiding value that informs decisions, behaviors and relationships. | Informal Formal |

| Guidance | Advisory information or recommendations intended to support decision-making or good practice, typically non-binding. | |

| Guideline | A statement, instruction or recommendation that is intended to assist decision-making or advise on a course of action. | |

| Norm | A shared expectation or informal rule about appropriate behavior, shaped by social, cultural or professional consensus. | |

| Code | A systematic collection of principles or rules, often codified to govern conduct within a profession, sector or organization. | |

| Benchmark | A standard or point of reference against which things may be compared, measured or judged. | |

| Standard | An agreed benchmark or level of performance used to measure, compare or regulate conduct or outcomes. | |

| Rule | A clearly defined instruction or directive that prescribes or prohibits specific actions, often within a formal system. | |

| Regulation | A legally enforceable requirement set by an authority to control or direct specific behaviors, processes or outcomes. | |

| Protocol | A formal set of rules or procedures that govern conduct and actions in official or structured situations. | |

| Policy | Authoritative high-level statement(s) guiding decisions, encompassing specific standards and rules. |

| Dates and Focus | Global Framework | Approach | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1990–2000 Legitimization of role of non-state actors in global governance | Rio Declaration and Agenda 21 (1992) | Promotion of guidelines, norms, codes and principles for participation of non-state actors, particularly the private sector. |

|

| 2000–2015 Strengthening partnership governance and accountability | Millennium Declaration and Millennium Development Goals (2000) WSSD Type II partnerships (2002) | Emphasis on cross-sector standards and rules for ensuring partnership governance and accountability, often via international accreditation bodies. |

|

| 2015 to date Meta-governance for SDG partnerships | Agenda 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (2015) | Focus on ensuring and enabling with the use of both formal and informal norms to support multi-stakeholder partnerships working towards achievement of SDG goals and targets. |

|

| Connectedness Adoption of a systems perspective that promotes multi-level linkages. |

|

| Engagement Active and continuous involvement of partners and relevant stakeholders. |

|

| Fairness Attention to power dynamics with equitable valuation of all partner contributions. |

|

| Respect Embracing of diversity and tolerance for different viewpoints. |

|

| Transparency Openness in partnership procedures, processes and relationships. |

|

| Bravery Willingness to challenge, test and experiment. |

|

| Transformation Dedication to ensuring meaningful and lasting change at different levels. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stott, L.; Murphy, D.F. A Principles-Based Approach for Enabling Multi-Stakeholder Collaboration: Addressing the Elusive Quest for Sustainable Development Partnership Standards. Standards 2025, 5, 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/standards5030023

Stott L, Murphy DF. A Principles-Based Approach for Enabling Multi-Stakeholder Collaboration: Addressing the Elusive Quest for Sustainable Development Partnership Standards. Standards. 2025; 5(3):23. https://doi.org/10.3390/standards5030023

Chicago/Turabian StyleStott, Leda, and David F. Murphy. 2025. "A Principles-Based Approach for Enabling Multi-Stakeholder Collaboration: Addressing the Elusive Quest for Sustainable Development Partnership Standards" Standards 5, no. 3: 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/standards5030023

APA StyleStott, L., & Murphy, D. F. (2025). A Principles-Based Approach for Enabling Multi-Stakeholder Collaboration: Addressing the Elusive Quest for Sustainable Development Partnership Standards. Standards, 5(3), 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/standards5030023