This section presents the results of the integrated longitudinal–temporal analysis conducted on the sustainability reports of H&M Group (2018–2023). While the topic modelling and KPI analyses were applied exclusively to these reports, the interpretation of the findings systematically draws upon the insights from the 48 articles obtained through the systematic literature review. The analysis aims to uncover the dominant leadership discourse themes over the six-year period (2018–2023) and to evaluate the extent to which these narratives align with the company’s stated sustainability objectives and measurable outcomes. In addition, the evolution of these themes is examined to assess potential shifts in leadership emphasis, stakeholder engagement strategies, and alignment with circular economy principles. This integration allows us to relate the empirical evidence from the company’s sustainability disclosures to the broader theoretical and empirical debates in the literature.

4.1. Results for Topic Modelling Analysis

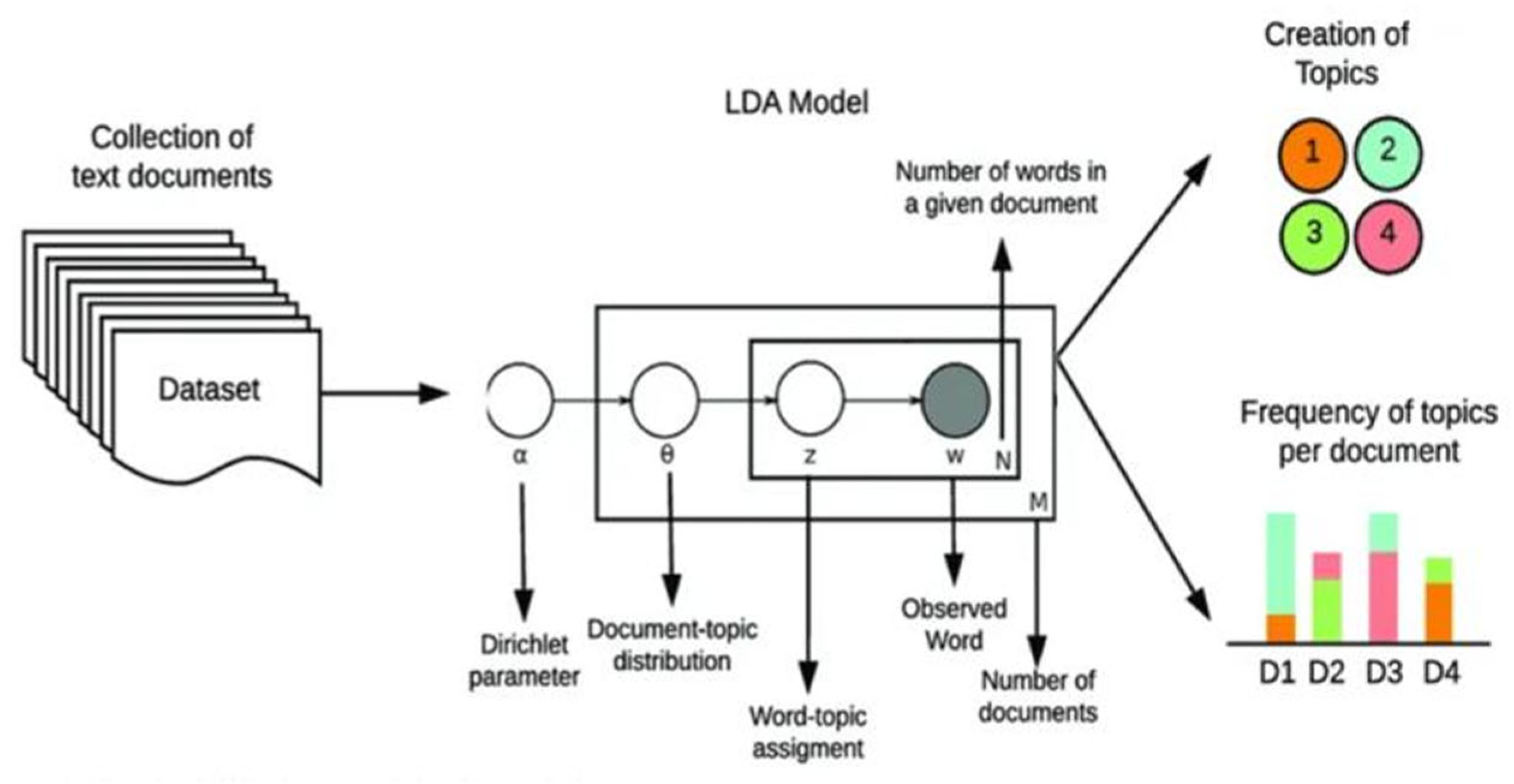

This study identified the two main topics present in each sustainability report and grouped their respective tokens, as presented in

Table 2,

Table 3,

Table 4,

Table 5,

Table 6 and

Table 7. The terms associated with each topic were extracted using the topic visualisation capabilities of the pyLDAvis tool, specifically employing its network visualisation mode. As an example, Topic 1 of the 2018 sustainability report is illustrated in

Figure 4.

The preponderance of the selected topic, which accounts for 94.3% of all tokens, is illustrated by its size and the estimated frequency of its terms, as compared to their general frequency within the corpus, following the caption of

Figure 5. All extracted information was compiled and is accompanied by a label representing the content of each topic, derived from the most frequent terms.

The classification performed by the researchers disregarded repetitions; that is, words appearing in both topics within a given report, which were deliberately omitted to facilitate the comprehension of the most important aspects and to differentiate the topics from one another. In addition to enhancing the readability of the results, this approach also contributed to the assignment of topic labels, which were designed to capture the thematic similarities among the main components of each topic, thereby providing meaningful interpretations of their content.

As shown in

Table 2, the first main topic extracted from the 2018 sustainability report encompasses key terms that allude to recurring themes in the field of study, such as sustainability and ethical practices in the supply chain. The assigned label for Topic 1, “

Sustainable fashion and ethical practices in the supply chain”, reflects this thematic focus. It is worth noting that these terms are interrelated, as ethical practices are essential for building a sustainable supply chain, aligning particularly with the social pillar of sustainability. Furthermore, Topic 1 is the most dominant in the document, representing 94.3% of the total token weight.

Topic 2, whose main terms include impact, issue, and overview, focuses on operational challenges and goals within the textile value chain. Hence, the chosen label for this topic is “operational dares and sustainability in the textile industry”. It is important to note, however, that this topic carries a significantly lower weight in the report, representing only 5.7% of the total token distribution.

As shown in

Table 3, the most relevant terms of Topic 1 in the 2019 sustainability report indicate a focus on corporate strategies, objectives, and the industry’s strategic vision, which justifies the assigned label “

Supplier and customer relationship management aligned strategies”. This label is consistent with the association of the extracted terms with elements of corporate planning and relationship management.

Topic 2 focuses on the social and environmental dimensions of sustainability, with particular emphasis on working conditions and social justice, challenges that are sensitive to the textile industry, and even more to the fast fashion sector [

14]. Accordingly, the assigned label is “

Social justice and circular sustainability”. In this topic, terms such as

work,

worker,

working,

people,

and wage reflect its social dimension, while

emission and future are related to environmental sustainability concerns.

Together, the two main topics in 2019 report highlight a shift in emphasis toward relationship management strategies and social sustainability challenges, reflecting the constant evolving discourse within the company’s leadership narratives.

As shown in

Table 4, Topic 1 from the 2020 sustainability report is strongly centred on corporate and operational aspects, with an emphasis on circularity practices and transparency as key elements in pursuing sustainable development. In that way, it was labelled as “

Sustainability and change management in the fashion and manufacturing industry”. It is worth noting that this topic carries a major weight in the analysed report, representing 97.1% of the total token distribution.

Topic 2 encompasses terms related to both the environmental domain (waste, impact, climate, water, and packaging) and the productive and operational domain (fashion, production, brand, strategy). This combination suggests a greater focus on responsible production and corporate branding, which led to the assigned label “Marketing, branding and environmental impacts of production”. It can be inferred that the 2020 report places a significant emphasis on the impacts of production processes, highlighting a business priority on the transition toward more responsible operational practices.

Together, the topics in the 2020 report reflect a leadership discourse that integrates sustainability ambitions with operational transparency and responsible production narratives.

As shown in

Table 5, the emphasis of the 2021 report is on circular business models. In Topic 1, this is evident through the presence of terms such as

production,

recycled,

material, and

emission, which are frequently associated with the circular economy [

8]. Based on this thematic focus, the chosen label is “

Data analysis, management and reporting in circular business”. The weight of 99.6% indicates that this topic is almost unanimous in the 2021 report, dominating its discourse.

In several aspects, Topic 2 differs significantly from Topic 1, both in its very low weight and in the distinct thematic content it represents. Topic 2 emphasised aspects within the operational and technical scope, incorporating terms related to sustainable materials, corporate reporting, and social responsibility. The topic presents a mix of terms across environmental, social, and reporting domains.

In this sense, Topic 2 can be viewed as an extension of Topic 1, as it translates the logic of sustainability into a more practical and measurable framework. Terms such as goals, reduction, assurance, and transparency reflect this orientation. The promotion of positive corporate sustainable performance has been increasingly associated with the role of disclosure and transparency, alongside the influence of international reporting standards such as the GRI framework [

33].

Thus, the label selected for Topic 2 is “Sustainability and transparency in operations”. Overall, the 2021 report appears to refine the themes addressed in previous years, advancing toward a more explicit focus on strategic management, organisational transparency, and the adoption of circular business models.

The overall structure of the 2021 report thus suggests a maturing leadership discourse, emphasising circularity, transparency, and performance-driven sustainability narratives.

As shown in

Table 6, Topic 1 from the 2022 report, with a weight of 64.1%, demonstrates a strong thematic concentration around ESG principles, with a particular focus on circularity, as the chosen label. Nevertheless, it must be mentioned that this topic shows a more systematic and technical characterisation compared to the themes presented in the reports of previous years.

Topic 2, while representing a smaller share of tokens (35.9%), still addresses several important themes, hence the reduced number of main words listed. However, the distinct nuance between the emphases of the two topics is illustrated by the presence of terms such as wage, worker, customer, progress, and right, which correspond to legal, social, and labour issues, and reflect underlying normative values. Accordingly, the label assigned to Topic 2 is “Law, equity, and social sustainability”.

As shown in

Table 7, the 2023 sustainability report represents a more balanced distribution between the two main topics compared to previous years. While Topic 1 continues to dominate the company’s discourse, with a weight of 60.5%, it maintains continuity with prior internal narratives, but it adopts a broader approach by addressing sustainability from an operational perspective with a governance profile. Accordingly, this topic was labelled as “

Material impact and operational transparency integration”.

Topic 2, which complements Topic 1, contributes to a more technical and operational refinement of the company’s sustainability discourse. It focuses on improvements in production processes, efficiency, and the rational use of resources, as reflected in the label “Nature, waste and resources eco-efficiency”. This topic underscores the company’s increasing attention to operationalising sustainability principles within its core production and resource management strategies.

Overall, the 2023 report reflects a more integrated leadership discourse that balances strategic sustainability considerations with operational transparency and resource efficiency, suggesting a further maturation of the company’s sustainability narrative.

The longitudinal analysis of the sustainability reports from 2018 to 2023 reveals a progressive evolution in the company’s leadership discourse. The earlier reports emphasised broad themes such as sustainable fashion, ethical practices, and social justice, while the later reports increasingly integrated technical, operational, and performance-driven language. Over time, there is a clear trend toward greater alignment between strategic sustainability priorities, circular economy principles, and transparent reporting practices. This suggests a maturing leadership narrative that seeks to balance corporate ambition with operational accountability and stakeholder expectations.

4.2. Results for KPIs Analysis

Based on the analysis of the KPIs presented in the company’s sustainability reports for the period 2018–2023, the main themes identified were Climate, Materials, Clothing, Waste, Packaging, Water, and Energy. It is worth noting that, as previously mentioned, occasional and non-recurring indicators disclosed in certain reports were excluded from the longitudinal analysis. The definitions of the specific indicators analysed were presented in

Table 1.

For the Climate indicators presented in

Table 8, the 2018 report established an initial goal of becoming “climate positive” by 2040. In 2019, this target was adjusted to state that climate positivity should be achieved by 2040 at the latest, a subtle but notable change that reflects a more flexible target. From 2021, the climate positivity goal was removed entirely, and reporting focused on year-to-year changes in scopes 1 and 2. In 2023, a quantitative target was introduced: an absolute reduction of 56% in all climate-related indicators by 2030, using 2019 as the base year. As of 2023, the reported absolute reduction was 29%. Considering this, H1 is accepted with caution, as the presence of climate-related targets and monitoring indicates alignment between leadership discourse and circular practices, but the removal of the initial “climate positive” commitment weakens the strength of this association. H2 is accepted with reservations, as the introduction of a measurable target supports a mediation effect between discourse and performance, though interim reductions are insufficient to confirm full achievement potential.

As shown in

Table 9, the materials’ KPIs reveal a generally positive trend. The goal of 100% recycled cotton or other sustainable sources was achieved in 2020. Recycled cotton or other sustainable sources increased from 95% in 2018 to 100% in 2020 and remained at that level through 2023. The proportion of recycled materials rose from 57% in 2018 to 85% in 2023. Recycled content increased from 1.4% in 2018 to 25% in 2023. Among the materials’ KPIs, the collection of used clothes for recycling is also monitored, as shown in

Table 9. In a public press release, the company stated its intention to “close the fashion cycle,” aiming to preserve the added value of textiles. Initially, the company set a target of collecting 25,000 pieces annually; however, full compliance was only achieved in 2019. The 2019 report updated this target to a goal of annual increases in the quantity of items collected, a target that has not been consistently met in subsequent years.

H1 is partially accepted, as the strong improvement in material sourcing aligns with leadership discourse, but the declining trend in clothing collection contradicts the stated ambition to “close the fashion loop.” H2 is partially accepted, since sourcing improvements could enhance performance, but inconsistent results in collection volumes limit the mediation effect.

Regarding packaging KPIs shown in

Table 10, the original goal of achieving 100% recycled packaging materials by 2030 was present until the 2020 report, but was subsequently removed. The target of 100% recycled or renewable materials by 2030 remained, with values of 68% in 2021, 71% in 2022, and 79% in 2023. Discrepancies were found in reported values (e.g., 71% for 2022 in the 2023 report versus 85% in the 2022 report). In this sense, H1 is weakly supported, as leadership discourse continues to reference a 2030 packaging goal but with diminished ambition and data inconsistencies. H2 is weakly supported, as partial progress is recorded, yet conflicting data undermine confidence in a mediation effect.

Another material indicator, specifically linked to the product, deals with the collection of used clothes for the recycling initiative promoted by the brand, shown as waste KPIs in

Table 11. Regarding the implementation of the in-store clothing recycling system, which enables the disassembly of old garments for the creation of new products, coverage remained relatively stable at around 63–64% during the first three years of the analysis (2018–2020), though no data were reported for subsequent years. H1 is not supported, as there is no evidence that leadership discourse sustained or expanded waste-related circular practices beyond the initial years. H2 is rejected due to the absence of recent data, preventing any confirmation of mediation between leadership discourse and performance.

For the energy consumption KPIs presented in

Table 12, once again, the goal changed over the studied period. Electricity intensity (kWh/m

2) decreased by 29% in 2023 compared to 2017, surpassing the original 25% reduction target set for 2025. Renewable energy use in operations remained between 90% and 96% during the period analysed, with a target of 100% by 2030. In this case, H1 is supported, as consistent reporting and achievement of energy goals reflect alignment with leadership discourse. H2 is supported, as measurable improvements in energy indicators suggest a mediation effect between discourse and sustainability performance.

Lastly, regarding water KPIs presented in

Table 13, they focus primarily on water consumption efficiency. Initially, the company aimed to achieve 100% implementation of water-efficient technologies by 2020. However, by the target date, only 85% implementation has been reached, and this KPI no longer appeared in subsequent reports. The second water KPI, recycled water used in production, showed steady progress, reaching 21% in both 2012 and 2022, though no value was reported for 2023. H1 is weakly supported, as early improvements indicate some alignment with leadership discourse, but the discontinuation of reporting limits confirmation. H2 is weakly supported, with some mediation evidence in the early years but insufficient longitudinal data to confirm a sustained effect.

Overall, the longitudinal analysis of KPIs reveals fluctuating levels of ambition, consistency, and transparency across different sustainability dimensions, providing valuable context for interpreting the evolving leadership discourse identified in the company’s sustainability reports. Regarding the hypothesis, H1 is fully supported only for Climate and Energy, partially supported for Materials, and weakly or not supported for Packaging, Waste, and Water. H2 is supported for Energy, cautiously accepted for Climate, partially supported for Materials, weakly supported for Packaging and Water, and rejected for Waste.