1. Introduction

The efficacy of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) must be determined via randomized, controlled trials (RCT) to gain general acceptance as evidence-based medicine. RCTs are generally considered the gold standard for distinguishing specific effects of intervention from non-specific effects [

1,

2]. Furthermore, where technically possible, double blinding is essential when investigating any therapies. Acupuncture is one of the most popular CAM therapies, and single blind (patient blinding) acupuncture placebo/sham needles have been developed to allow acupuncture studies to more closely achieve the most rigorous methodological standards [

3,

4]. These needles are the best possible blinding devices for clinical acupuncture trials [

5,

6]; however, they are not designed to blind acupuncturists to the administration of a real or placebo/sham needle. In acupuncture research, double blinding had been considered almost impossible to achieve because blinding an acupuncturist seemed impossible due to the nature of the procedure [

7,

8,

9]. This unblinding of practitioners in single blind studies produces an undeniable potential bias [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. We designed skin-touch placebo needles for double (practitioner-patient) blinding with matched penetrating needles and evaluated the effectiveness of these needles in an attempt to alleviate the methodological difficulty of blinding practitioners [

16,

17,

18,

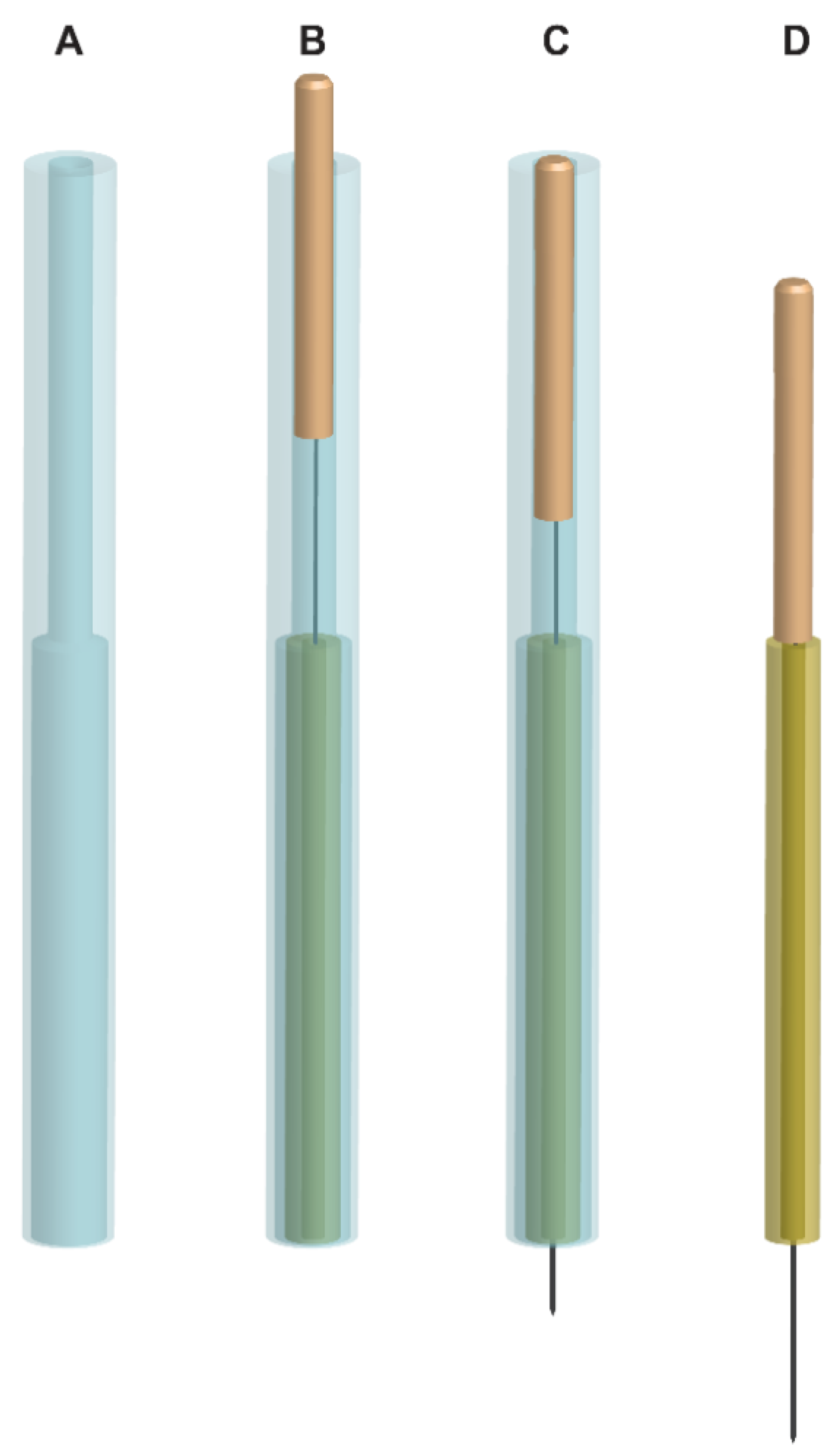

19].

In previous validation studies for double blinding using the penetrating and skin-touch placebo needles, at least half of the guesses made by experienced acupuncturists after each needle application did not coincide with the nature of needles [

16,

17,

18]. Furthermore, we designed no-touch placebo needles, where the needle tip does not reach the skin, to settle the controversy of whether skin-touch placebo needles are true placebos [

9,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. The no-touch placebo needles effectively blinded practitioners [

22]. When acupuncture-experienced subjects were treated with the skin-touch placebo and penetrating needles, they incorrectly guessed half of the skin-touch placebo needles as penetrating [

18]. Furthermore, more than 30% of penetrating needles were guessed as skin-touch placebos by the subjects [

17,

18]. However, full patient blinding became difficult to achieve when the no-touch placebo needle was used [

23,

24], although most subjects were not certain of the accuracy of their guesses for no-touch placebo needles and penetrating needles [

23,

24]. We believe that these needles are the best safeguard against bias in acupuncture studies.

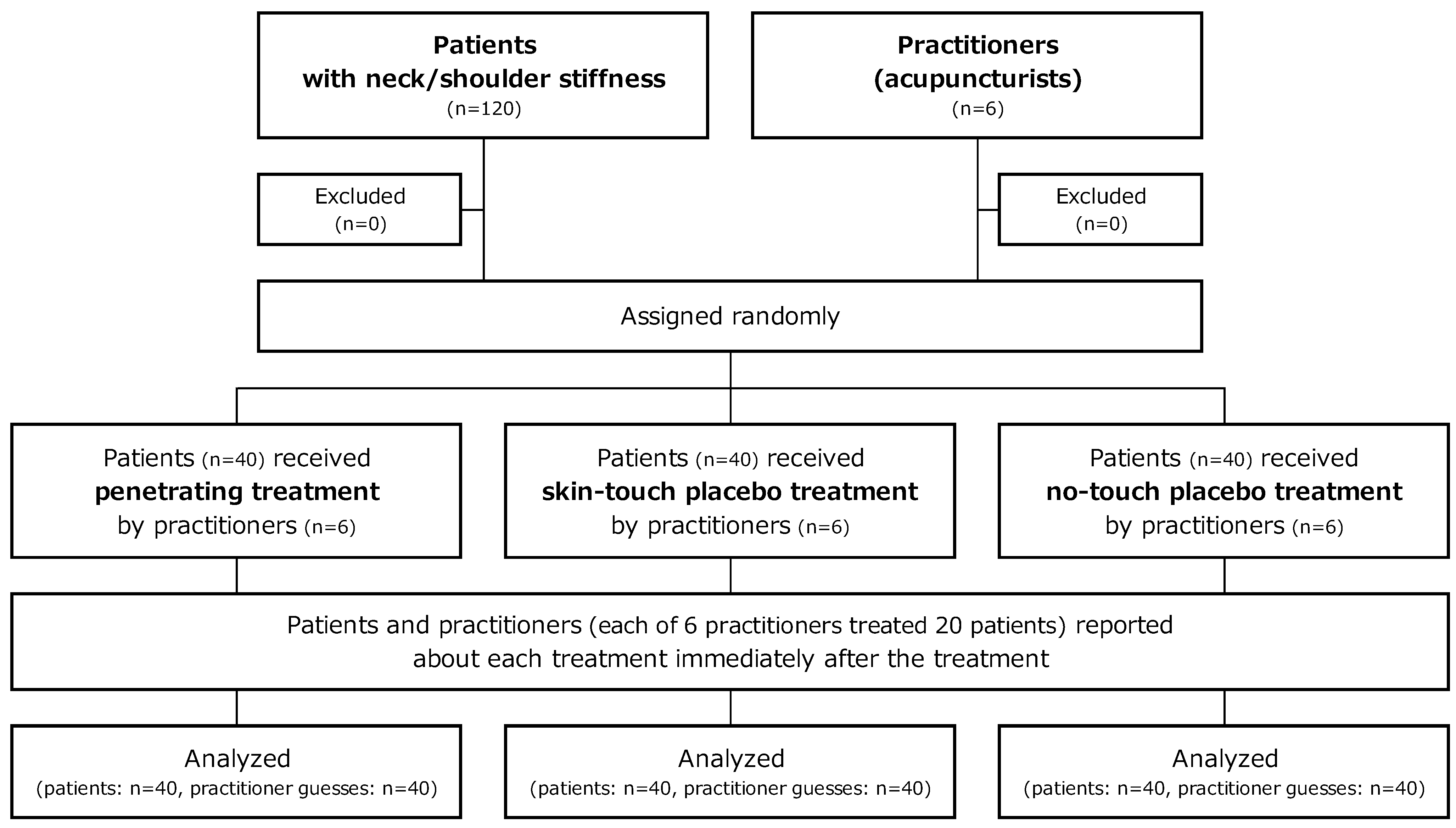

In our previous validation studies, practitioners and subjects were asked to guess the type of needle used after each needle application. Therefore, the question remains as to whether a treatment using multiple needles and repeated applications can blind practitioners and patients in clinical trials. In the present study, practitioners and subjects guessed the type of needle used during a treatment consisting of four needles of the same type after all needle applications. The aim of this study was to assess the potential to blind practitioners and patients to treatments of multiple penetrating, skin-touch placebo, or no-touch placebo needles designed for double blinding in randomized controlled trials.

4. Discussion

We assessed the potential to blind practitioners and patients to acupuncture treatment modes using multiple penetrating, skin-touch placebo, and no-touch placebo needles. The kappa value for practitioner treatment mode guesses showed poor agreement. The confidence level for correct patient guesses was larger than for correct practitioner guesses, and the kappa value for patient treatment mode guesses indicated a moderate level of agreement. These results suggest the practitioners were blinded to the treatment mode using these needles, but patient blinding was insufficient. Considering that our patients were acupuncture students, treatment mode was guessed without complete confidence and their confidence in their incorrect guesses was also high, so these acupuncture needles do have potential for double blinding in clinical trials. However, further studies are needed to improve the effectiveness of double blinding with acupuncture needles used in this study to achieve satisfactory patient blinding.

For practitioner blinding, the kappa value showed a poor level of accuracy, and practitioners with more years of acupuncture experience did not make more correct guesses; the low certainty of the practitioner guesses support the conclusion that practitioners were blinded to treatment mode using the multiple needles. Correct guessing was not predictable from the level of practitioner confidence because of the low certainty of their guesses of being correct, and there was no significant difference in their confidence when making correct and incorrect guesses. The majority of the needles were guessed from “feeling of needle insertion or/and removal,” and the respective numbers of correct and incorrect guesses using these feelings through needle manipulation fit an ideal ratio, which means it was inherently difficult for acupuncturists to identify the treatment mode using the same multiple needles. Furthermore, the number of penetrating, skin-touch placebo, and no-touch placebo guesses or unidentified guesses among penetrating, skin-touch placebo and no-touch placebo treatment for each practitioner was not statistically different; but was different among the six practitioners. This indicated that practitioners actually guessed by their own individual perception, which may be different from other practitioners. These results suggest that the needles used in this study for double blinding are a useful tool for practitioner blinding in clinical trials.

For patients, the kappa value showed a moderate level of agreement, and their confidence in their correct guesses was greater than that of the practitioners. This suggests on the face of it that patient blinding was not sufficient. Given the relatively large number of treatment applications that were correctly guessed with high confidence by patients, we must conclude that it was difficult to fully blind patients to the treatment mode using the same needles. Patient blinding is inherently difficult in acupuncture treatment, because penetrating and skin-touch needles induce patient sensations but no-touch needles do not; for example, this is quite different to pill administration

versus placebo administration where the sensation is the same. Therefore, we believe that the patients in this study had a relatively high confidence in their guesses regardless of whether they were accurate or not. In our validation study series, we chose acupuncture students as subjects because they were experienced in receiving acupuncture and knew needle sensations well, which means they should be much more difficult to blind than the general public. Considering the difficultly in achieving full double blinding in pharmacological randomized trials [

28] and the added difficulty (skin sensations) acupuncture poses for double blinding, it may be the reasonable results that the majority of the patients were not completely confident about their guesses with the close kappa coefficient to the fair level of accuracy. It must be emphasized that patients who incorrectly guessed treatment mode did appear to have high confidence when they were informed that they would receive either penetrating, skin-touch placebo, or no-touch placebo acupuncture. Furthermore, the kappa coefficient between practitioner and patient guesses was very close to 0, which means patient confidence in correct guesses did not affect practitioner guesses and vice versa. In fact, there were no treatments guessed with full confidence for both the practitioner and the patient. Given these findings, acupuncture needles for double blinding may have a limitation for patient blinding to some extent, and therefore, complete patient blinding using these needles cannot be guaranteed.

Given that the kappa value for patient blinding in this study was at a moderate level of accuracy, we must be aware of impartial guesses and treatment outcomes that may show bias. Unavoidable needle sensations or the absence of sensations felt by patients gives the patient a relatively strong positive or negative guide as to the treatment given. We believe analysis of the treatment outcome according to the patient guess is essential to understanding the effectiveness of acupuncture. If practitioner blinding can be achieved in an acupuncture study, subgroup analysis would be meaningful to investigate the healing power of the patient mind. For example, we could undertake a patient subgroup analysis using the nine groups in a 3 × 3 factorial assortment, e.g., penetrating, skin-touch placebo, or no-touch placebo treatment paired with either “penetrating,” “skin-touch,” or “no-touch” in patient guess. This may reveal the specific effects of acupuncture, placebo effects on patients, and the efficacy of acupuncture in routine clinical care. Practitioner blinding is crucial to enable us to understand the healing power of the patient mind entangled with needle insertion. From this perspective, in blinded acupuncture studies it is informative to ask patients what treatment they thought they received and how certain they felt that their guess was correct.

In the Japanese style of acupuncture, the simple insertion technique, whereby the needle is removed immediately after needle insertion to the desired depth, is commonly used in real treatment as well as the needle retention technique, whereby inserted needles reach the desired depth and are maintained in place for a desired time [

29]. We did not use pedestals to set up and erect the needle at an acupoint in this study, because we employed only the simple insertion technique to keep needle application in the same way as in real treatment of neck/shoulder stiffness as much as possible [

29]. The patient blinding effects may have been affected with the use of pedestals; however, there has been no study in which practitioners and subjects guessed various treatment modes using the same multiple needles with a pedestal after completion of all needle applications as in the present study. Therefore, findings from the present study cannot be compared with previous study findings [

22,

23,

24] and consistency cannot be established. Further validation research using these acupuncture needles with pedestals and employing the needle retention technique are needed to investigate whether the skin-touch stimulation with the pedestal has an influence on patient blinding.

We employed the tapping-in method to penetrate the skin using an outer guide tube, and then the needle is inserted further using the alternating twirling technique according to the Japanese style of acupuncture. We designed an outer guide tube to improve the usability of the needles for double blinding to employ the tapping-in method for smooth, fast, and easy skin penetration [

24]. In fact, when using the tapping-in method even without a guide tube, blinding is apparently improved and the frequency of painless skin penetration with the penetrating needles is increased compared with the twirling-in method [

23,

24]. The difficulty in employing the tapping-in method with needles for blinding trials [

24] was overcome by using the outer guide tube, and therefore, treatments employing these needles have become much more similar to ordinary acupuncture treatment.

This study had the following limitations. We did not administer continuous treatments, and therefore, we must validate the blinding effect of the needles for practitioners and patients using multiple treatments. Insertion with the penetrating needles was exclusively 5 mm to the neck/shoulder. The needles were removed immediately after needle insertion to the specific depth, and therefore, in future studies, the needles should be validated when they remain and are manipulated in the body. The number of acupuncturists was relatively small; therefore, the conclusion on practitioner blinding should be carefully interpreted. The subjects were exclusively acupuncture students who had a moderate knowledge of acupuncture, and they were not asked to report the clues used in making their guesses. Therefore, the blinding efficacy on patients should be tested with acupuncture-naïve subjects and with consideration of the various clues the patients use to identify the needles. Further research is necessary to address these limitations and to improve these needles into more effective double blind acupuncture devices by considering practitioner and patient clues used for guesses.