Abstract

Background/Objectives: Oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) and conduct disorder (CD) are important behavior disorders in children and adolescents, often linked with long-term psychosocial problems. Antipsychotics are frequently prescribed to manage severe symptoms and improve behavior, but their efficacy in this population is still unclear and a lot of physicians are remittent in prescribing them. This systematic review aims to assess the effectiveness of antipsychotic treatment in reducing symptoms associated with ODD and CD in children and adolescents. Methods: Studies that investigated how effective antipsychotic treatments are for children and teens diagnosed with oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) and conduct disorder (CD) were reviewed. Only studies that met a few main criteria were included: participants were between 5 and 18 years old with an ODD or CD diagnosis; the treatment could be any type of antipsychotic, whether typical or atypical; the accepted study designs were randomized controlled trials (RCTs), cohort studies, systematic reviews with meta-analysis, or observational studies. The outcomes of interest were reductions in aggressive or defiant behaviors, improvements in social functioning, and the occurrence of any adverse effects from the medications. There was no restriction on the language of publication, and studies published from 2000 to 2024 were considered. Studies that focused only on non-antipsychotic drugs or behavioral therapies, as well as case reports, expert opinions, and non-peer-reviewed articles did not meet the inclusion criteria. Results: The review consisted of 13 studies. The results suggest that some antipsychotic drugs—especially atypical antipsychotics—can substantially reduce aggressive and defiant behavior in children and adolescents who have oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) or conduct disorder (CD). Common side effects of these medications include weight gain, sedation, and metabolic problems. Conclusions: Although adverse effects are a concern, the potential of these medications to manage disruptive behaviors should not be overlooked. When used in combination with behavioral therapy and other forms of treatment, antipsychotics can markedly improve the outcomes of these very difficult-to-treat patients. Clinicians who treat these patients need to consider antipsychotics as a serious option. If they do not, they are denying their patients medication that could greatly benefit them.

1. Introduction

Conduct disorder (CD) and oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) are disruptive behavior disorders that occur in children and adolescents. They are among the most common mental disorders affecting young people [1]. These two disorders appear to be closely related, and children and adolescents diagnosed with them frequently exhibit aggressive, defiant, and antisocial behaviors [2]. These behaviors can lead to many significant challenges in a young person’s life, including academic problems, trouble with family and friends, and an increased risk of serious antisocial behavior and criminal activity in the future [3]. The treatment of these disorders is multifaceted, with behavioral therapies, family interventions, and medications being cornerstone approaches [4]. Among pharmacological treatments, antipsychotic medications have been widely used, particularly for individuals with more severe presentations of aggression and defiance [5].

The debate is ongoing over how well disruptive behaviors of children with oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) and conduct disorder (CD) respond to treatment with antipsychotic medications [6]. Atypical antipsychotic drugs (e.g., risperidone, aripiprazole), which have been more recently developed, do show some promise in reducing aggression and improving overall behavior, at least in the short term [7]. But what does the use of these drugs in children portend for both mental and physical health? Concerns have been raised about potential side effects including (but not limited to) weight gain, sedation, and disturbances of metabolism [8].

Given the rather tenuous evidence and the potential dangers linked to antipsychotic treatment, it is important to determine whether these medications are effective for something like oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) or conduct disorder (CD). The purpose of this systematic review is to determine if antipsychotic drugs do (or do not) reduce disruptive behaviors. A secondary goal is to assess their corresponding side effects.

2. Materials and Methods

This systematic review was conducted following the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines to ensure transparency, rigor, and methodological quality. The review protocol was registered with PROSPERO (ID: CRD420251009839).

The review encompassed studies that assessed the effectiveness of antipsychotic medications when given to children and adolescents with ODD and CD. Eligible studies had to meet a set of criteria:

- Population: The studies had to involve participants who were children or adolescents (aged 5 to 18) with a diagnosis of ODD or CD.

- Intervention: The studies had to evaluate the administration of any type of antipsychotic medication, whether typical or atypical.

- Study Design: Only randomized controlled trials (RCTs), cohort studies, systematic reviews with meta-analysis, and observational studies were included.

- Outcome Measures: The studies had to report some measures that indicated how well the medication was working.

- Publication Language: The studies could be published in any language. If any study was published in a language in which the authors were not fluent, translation tools (like DeepL) were used.

- Date: The studies could have any date of publication from 2000 to 2024.

Studies were excluded based on the following criteria:

- Population: Studies where ODD and/or CD were not the primary diagnosis. Studies where individuals had low IQ (<70) or comorbid autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

- Intervention: Studies that focused solely on non-antipsychotic pharmacological interventions or solely on behavioral therapies.

A thorough literature search using an electronic database search was performed to find studies that assess the effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in treating youths diagnosed with ODD and CD. The subsequent electronic databases were investigated:

- PubMed/MEDLINE

- PsycINFO

- Cochrane Library

- EMBASE

- Web of Science

The terms of the search combined keywords and medical subject headings (MeSH) that pertained to the population, interventions, and outcomes of interest. The precise search string that was used was

(“Oppositional Defiant Disorder” OR “Conduct Disorder”)

AND

(“antipsychotic treatment” OR “atypical antipsychotics” OR “Risperidone” OR “Aripiprazole”)

AND

(“children” OR “adolescents”)

AND

(“aggression reduction” OR “behavioral improvement”)

To find more studies that possibly fell outside the database searches, a tool called Connected Papers was used. Connected Papers is a visual tool that maps the relationships between scientific papers based on co-citation and bibliographic coupling. This tool helped uncover related studies by visualizing networks of research papers connected to the key articles already identified. The following steps were taken using Connected Papers:

- Seminal papers identified from the initial search were input into the tool.

- The network of connected papers was explored to find additional relevant studies.

- The titles and abstracts of these connected papers were screened for inclusion.

The reference lists of all included studies and pertinent systematic reviews were manually searched to find additional studies that met our inclusion criteria.

All identified studies underwent a two-step screening process. To start, the titles and abstracts of all articles were reviewed to determine relevance to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Articles that passed this first test were then reviewed in full—two reviewers working independently decided on each article’s eligibility. Where the reviewers’ judgments did not agree, the two first discussed the case. If they could not come to a consensus, a third reviewer was brought in to break the tie.

A standardized form was used to extract the data. The data extracted included

- The study characteristics (author, year, country, study design).

- The characteristics of the participants (age, gender, diagnostic criteria, sample size).

- The intervention details (type of antipsychotic, dosage, treatment duration).

- The outcome measures (changes in behavior, social functioning, adverse effects).

- The results (statistical findings, effect sizes, significance levels).

Two reviewers performed the data extraction independently. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus.

In this review, the risk of bias was assessed at the study level.

For experimental studies, particularly randomized controlled trials (RCTs), the Cochrane Risk of Bias (RoB) tool was employed, as it is highly recommended for assessing methodological rigor in such studies.

For systematic reviews of observational studies, the Risk of Bias in Non-randomized Studies of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool was applied. Alternatively, the quality assessment criteria provided by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) were considered, depending on the study design and characteristics.

Only studies classified as having a low risk of bias were included in this review. Studies with a high or unclear risk of bias were excluded to ensure the reliability of the findings.

3. Results

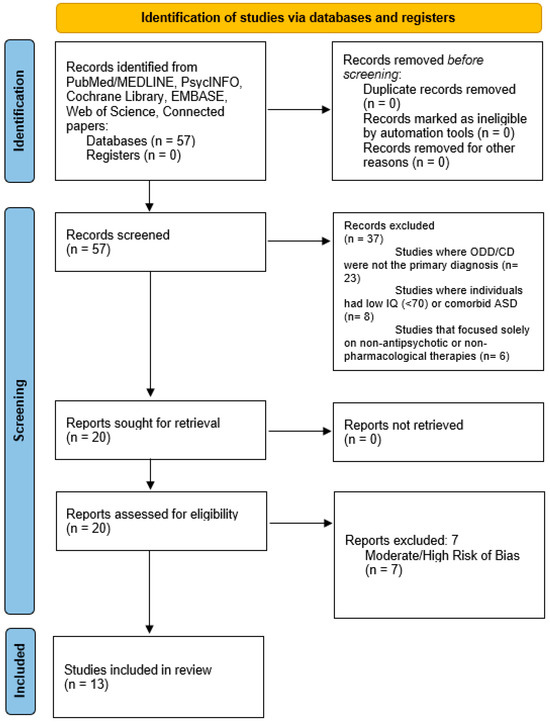

Of the 57 studies retrieved for detailed evaluation, 13 were fit for inclusion in the present study. The study selection process is illustrated in Figure 1, following the PRISMA flow diagram.

Figure 1.

Paper selection flowchart.

3.1. General Characteristics of the Included Studies

Out of the 13 studies, 4 were RCTs, 2 were longitudinal, 3 were open label, 1 was retrospective, and 3 were systematic reviews with meta-analyses.

The psychopharmacologic therapies investigated predominantly involved atypical antipsychotic medications, particularly risperidone, aripiprazole, and olanzapine. Some trials looked at typical antipsychotics such as haloperidol and chlorpromazine; however, most examined the new atypical agents.

The key characteristics of the included studies—including study type, population, intervention, and outcome measures—are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies. In each intervention we highlighted the antipsychotic(s) used.

3.2. Narrative Analysis

This systematic review encompassed 13 studies that assessed the efficacy and safety of atypical antipsychotics and various other interventions for managing conduct disorder (CD) and oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) in children and adolescents. A summary of key findings follows.

3.2.1. Atypical Antipsychotics: Efficacy

- Juárez-Treviño et al. (2019) [9]: Clozapine and risperidone were both found to be effective in significantly reducing aggression in children with conduct disorder. Clozapine showed some superior effects on externalizing symptoms and delinquency (p-values: 0.039, 0.010, 0.021).

- Pringsheim et al. (2015) [6]: This meta-analysis of 11 RCTs (8 on risperidone, 1 each on quetiapine, haloperidol, and thioridazine) found that atypical antipsychotics significantly reduced disruptive behavior in children with ODD or CD, with an SMD of 0.60 (95% CI 0.31 to 0.89).

- Loy et al. (2017) [10]: This systematic review found atypical antipsychotics to be effective—particularly, risperidone—in reducing irritability and aggression, using tools such as the Aberrant Behavior Checklist to measure outcomes.

- Findling et al. (2006) [15]: Quetiapine produced some significant improvements in aggression and behavioral symptoms among children diagnosed with conduct disorder. Of note was the significant weight gain across subjects that occurred during the trial (4.6 ± 3.9 kg).

- A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study by Connor et al. (2008) [22] found that compared to placebo, quetiapine significantly improved aggressive behaviors, with eight of nine subjects on quetiapine showing clinical improvement (p = 0.0006).

- Shafiq et al. (2018) [19]: A systematic review comparing risperidone to placebo in children with conduct problems showed significant reductions in disruptive behavior and aggression, with an SMD of -0.64 (95% CI −0.89 to −0.40). Weight gain was noted in the risperidone group.

3.2.2. Comparative Effectiveness

- Gadow et al. (2016) [11]: A longitudinal study comparing parent training combined with stimulant plus placebo versus stimulant plus risperidone showed both interventions were effective, but the addition of risperidone did not provide significant extra benefit.

- Reyes et al. (2006) [13]: Significantly, the maintenance treatment with risperidone delayed the time to recurrence of symptoms compared to placebo. This underscores the continued treatment imperative for maintained control of aggression and, presumably, for improved psychosocial functioning.

- Findling et al. (2009) [17]: Compared to placebo, aripiprazole reduced aggression scores, but side effects, including sedation, necessitated dose adjustments during the study.

- Masi et al. (2006) [14]: Efficacy was demonstrated with olanzapine in reducing aggression, with 60.9% of patients showing positive response to treatment; however, weight gain was noted.

3.2.3. Augmentation and Combination Therapy

- Gadow et al. (2014) [18]: A 9-week longitudinal study comparing basic stimulant treatment to augmented therapy (stimulant plus risperidone) showed that augmentation provided greater reductions in aggression with peers but had no significant effect on ADHD or ODD symptoms.

- Kronenberger et al. (2007) [16]: After treating the initial stage with methylphenidate, quetiapine was prescribed for the remaining aggressive symptoms in adolescents. This combination resulted in a significant (p < 0.01) decrease in aggression scores compared to previous ranks in which only methylphenidate was administered.

3.2.4. Dose-Dependent Efficacy and Long-Term Management

- Findling et al. (2000) [12] carried out a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial with youths with conduct disorder. They found that risperidone was better than placebo in reducing aggression as measured by the Rating of Aggression Against People and Property (RAAPP).

- Gadow et al. (2014) [18]: A study involving 168 children with severe disruptive behavior reported significant improvements in aggression using parent training combined with stimulant medication. The study underscored the importance of individualized dosing to optimize treatment effects.

3.2.5. Safety and Adverse Effects

- Reyes et al. (2006) [13]: Found that maintenance treatment with risperidone delayed the return of symptoms but was linked to weight gain and other adverse effects. The return of symptoms was significantly delayed in patients who continued risperidone.

- Connor et al. (2008) [22]: Children treated with quetiapine experienced significant weight gain compared to those receiving a placebo. Although it was very effective for managing aggression, quetiapine had some very concerning side effects—profound sedation and an increased appetite.

- Shafiq et al. (2018) [19]: Common adverse effects among children treated with risperidone included weight gain and sedation. However, the authors found risperidone to have significant efficacy in reducing conduct problems in children.

3.2.6. Summary of Effectiveness

In general, atypical antipsychotics, like risperidone, olanzapine, and quetiapine, worked well to reduce aggression and improve behavior in children and adolescents with disruptive behavior disorders. These drugs were effective when used alone (monotherapy) and when combined with other medications (augmentation), especially stimulant medications (e.g., methylphenidate) when children were diagnosed with a disorder like ADHD. Combining these drugs with antipsychotics often led to better outcomes for children and adolescents with serious behavior problems.

3.2.7. Safety Considerations

Adverse events were consistently reported, most notably weight gain, sedation, and metabolic changes, which all potentially impact heart health. Reported weight changes were of special concern, with self-reported weight changes from baseline averaging a gain of about 4 kg across RCTs, this weight gain being highest with olanzapine [14]. Weight gain carries with it a host of negative health consequences and therefore should be taken into account when prescribing these drugs, despite the clear evidence of their efficacy.

4. Discussion

4.1. Comorbidity and Its Impact on Treatment Outcomes

Due to the complex nature of both CD and ODD, individuals with a primary diagnosis of one of these conditions very commonly have comorbid conditions, namely ADHD, OCD, anxiety and mood disorders [23].

While we tried to minimize the effects of these conditions by only selecting studies where the primary diagnosis was either CD or ODD and excluding those where patients had low IQ or ASD, comorbidities like ADHD complicate the already difficult problem of diagnosing and treating conduct problems for two reasons.

First, they can make the symptoms of opposition and defiance or conduct problems less apparent and thus more difficult to identify.

Second, some studies do not provide enough detail about the management of comorbidities, which limits our understanding of how these conditions might affect the outcomes of the primary treatments being studied [24]. This is an important issue for future research to resolve [25].

4.2. Limited-Time Follow-Up

Most studies follow participants for only a few months, which means we have scant data on the effect of these medications on children and adolescents over longer stretches of time. This dearth of data pertains not just to long-term secondary effects, but also to the rate of progression to antisocial personality disorder [26].

4.3. Implications for Current Practice

This literature review of existing research on the use of antipsychotic medications in children and adolescents with ODD and CD provides insights into the disorders’ treatment and the medications’ safety, and efficacy. The review includes a wide range of study designs—from RCTs to cohort and observational studies—that together form a picture of the existing evidence.

Moreover, it includes as a primary criterion for inclusion in the analysis that the studies must have ODD or CD as their primary focus. That makes the conclusions drawn in the review more reliable, since it is one of the few reviews that singles out these disorders for treatment with antipsychotics.

Additionally, there is a need for further research into tailored interventions for children and adolescents without comorbidities, as they are often overlooked in existing studies, which tend to focus on more complex cases involving multiple conditions [27].

4.4. Stigma in Clinical Practice

One of the surprising things brought to life by this review is the clear stigma that still exists around not only these patients (pediatric population) but also the use of antipsychotic treatment in this age segment [28].

This is clear by the fact that very few studies are conducted on these patients, reflecting a reluctance to study these children and adolescents [10]. The studies that exist are all conducted by a few psychiatrists, while the study of adult populations, especially those with more common and less socially frowned-upon pathologies (like depression) have a much more extensive number of researchers and papers.

As medical professionals, we should strive to minimize our biases and prejudices when conducting scientific research. And even though eliminating them is not possible, we think papers like this one help in shedding light on this reality and in moving the needle [29].

Moreover, this review also shows the hesitation in giving antipsychotic treatment to pediatric populations. This is evidenced by the fact that there already exists plenty of evidence that these medications, when allied with other modalities of treatment, provide the most efficacious treatment of these conditions. So, why are we so unwilling to implement a tool that we have had for so long?

5. Conclusions

This systematic review illustrates that pharmacotherapy, especially with clozapine or risperidone, is effective for reducing aggressive and disruptive behavior in children and adolescents diagnosed with ODD and CD. Although clozapine has been studied less frequently, its effectiveness seems to surpass that of risperidone, especially regarding improving delinquency traits and overall functioning. However, this agent also warrants mention in the context of pharmacovigilance because of the potential for serious side effects.

Older “typical” antipsychotics like haloperidol and thioridazine do not seem as effective for these behavioral disorders and have a profile of serious side effects.

Other antipsychotics like quetiapine and ziprasidone, which seem to work well in other populations, remain unstudied and, therefore, their efficacy cannot be determined. Additionally, there is an absence of research on children under the age of five, underscoring a critical gap in the literature.

Overall, antipsychotics are a helpful tool for managing aggression and irritability in children and adolescents with ODD and CD, providing a valuable mechanism of control when other treatment options have failed.

Further large-scale, long-term studies are required to grasp fully the long-term efficacy and safety of these medications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.S. and P.A.; methodology, N.S. and J.A.; software, N.S.; validation, N.S., P.A. and J.A.; formal analysis, N.S. and P.A.; investigation, N.S. and P.A.; resources, N.S. and P.A.; data curation, N.S. and P.A.; writing—original draft preparation, N.S.; writing—review and editing, P.A.; visualization, N.S. and J.A.; supervision, J.A.; project administration, J.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in the analysis were derived from previously published studies, which can be accessed via the respective sources referenced throughout the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Fairchild, G.; Hawes, D.J.; Frick, P.J.; Copeland, W.E.; Odgers, C.L.; Franke, B.; Freitag, C.M.; De Brito, S.A. Conduct disorder. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2019, 5, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loeber, R.; Burke, J.D.; Lahey, B.B.; Winters, A.; Zera, M. Oppositional defiant and conduct disorder: A review of the past 10 years, part I. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2000, 39, 1468–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fergusson, D.M.; Horwood, L.J.; Ridder, E.M.; Beautrais, A.L. Subthreshold depression in adolescence and mental health outcomes in adulthood. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2005, 62, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazdin, A.E. Practitioner review: Psychosocial treatments for conduct disorder in children. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 1997, 38, 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pappadopulos, E.; Woolston, S.; Chait, A.; Perkins, M.; Connor, D.F.; Jensen, P.S. Pharmacotherapy of aggression in children and adolescents: Efficacy and effect size. J. Can. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2006, 15, 27–39. [Google Scholar]

- Pringsheim, T.; Hirsch, L.; Gardner, D.; Gorman, D.A. The Pharmacological Management of Oppositional Behaviour, Conduct Problems, and Aggression in Children and Adolescents with Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, Oppositional Defiant Disorder, and Conduct Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Part 2: Antipsychotics and Traditional Mood Stabilizers. Can. J. Psychiatry 2015, 60, 52–61. [Google Scholar]

- Findling, R. Atypical antipsychotic treatment of disruptive behavior disorders in children and adolescents. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 2008, 69 (Suppl. 4), 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Correll, C.U.; Manu, P.; Olshanskiy, V.; Napolitano, B.; Kane, J.M.; Malhotra, A.K. Cardiometabolic risk of second-generation antipsychotic medications during first-time use in children and adolescents. JAMA 2009, 302, 1765–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juárez-Treviño, M.; Esquivel, A.C.; Isida, L.M.L.; Delgado, D.Á.G.; de la OCavazos, M.E.; Ocañas, L.G.; Sepúlveda, R.S. Clozapine in the Treatment of Aggression in Conduct Disorder in Children and Adolescents: A Randomized, Double-blind, Controlled Trial. Clin. Psychopharmacol. Neurosci. 2019, 17, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loy, J.H.; Merry, S.N.; Hetrick, S.E.; Stasiak, K. Atypical antipsychotics for disruptive behaviour disorders in children and youths. Cochrane. Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 8, CD008559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadow, K.D.; Brown, N.V.; Arnold, L.E.; Buchan-Page, K.A.; Bukstein, O.G.; Butter, E.; Farmer, C.A.; Findling, R.L.; Kolko, D.J.; Molina, B.S.; et al. Severely Aggressive Children Receiving Stimulant Medication Versus Stimulant and Risperidone: 12-Month Follow-Up of the TOSCA Trial. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2016, 55, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Findling, R.L.; Mcnamara, N.K.; Branicky, L.A.; Schluchter, M.D.; Lemon, E.; Blumer, J.L. A Double-Blind Pilot Study of Risperidone in the Treatment of Conduct Disorder. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2000, 39, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reyes, M.; Buitelaar, J.; Toren, P.; Augustyns, I.; Eerdekens, M. A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study of Risperidone Maintenance Treatment in Children and Adolescents with Disruptive Behavior Disorders. Am. J. Psychiatry 2006, 163, 402–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masi, G.; Milone, A.; Canepa, G.; Millepiedi, S.; Mucci, M.; Muratori, F. Olanzapine treatment in adolescents with severe conduct disorder. Eur. Psychiatry 2006, 21, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Findling, R.L.; Reed, M.D.; O’Riordan, M.A.; Demeter, C.A.; Stansbrey, R.J.; McNamara, N.K. Effectiveness, safety, and pharmacokinetics of quetiapine in aggressive children with conduct disorder. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2006, 45, 792–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronenberger, W.G.; Giauque, A.L.; Lafata, D.E.; Bohnstedt, B.N.; Maxey, L.E.; Dunn, D.W. Quetiapine addition in methylphenidate treatment-resistant adolescents with comorbid ADHD, conduct/oppositional-defiant disorder, and aggression: A prospective, open-label study. J. Child. Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2007, 17, 334–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Findling, R.L.; Kauffman, R.; Sallee, F.R.; Salazar, D.E.; Sahasrabudhe, V.; Kollia, G.; Kornhauser, D.M.; Vachharajani, N.N.; Assuncao-Talbott, S.; Mallikaarjun, S.; et al. An Open-Label Study of Aripiprazole: Pharmacokinetics, Tolerability, and Effectiveness in Children and Adolescents with Conduct Disorder. J. Child. Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2009, 19, 431–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadow, K.D.; Arnold, L.E.; Molina, B.S.G.; Findling, R.L.; Bukstein, O.G.; Brown, N.V.; McNamara, N.K.; Rundberg-Rivera, E.V.; Li, X.; Kipp, H.L.; et al. Risperidone added to parent training and stimulant medication: Effects on attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, and peer aggression. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2014, 53, 948–959.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiq, S.; Pringsheim, T. Using antipsychotics for behavioral problems in children. Expert. Opin. Pharmacother. 2018, 19, 1475–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahangard, L.; Akbarian, S.; Haghighi, M.; Ahmadpanah, M.; Keshavarzi, A.; Bajoghli, H.; Bahmani, D.S.; Holsboer-Trachsler, E.; Brand, S. Children with ADHD and symptoms of oppositional defiant disorder improved in behavior when treated with methylphenidate and adjuvant risperidone, though weight gain was also observed—Results from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Psychiatry Res. 2017, 251, 182–191. [Google Scholar]

- Aman, M.G.; Bukstein, O.G.; Gadow, K.D.; Arnold, L.E.; Molina, B.S.G.; McNamara, N.K.; Rundberg-Rivera, E.V.; Li, X.; Kipp, H.; Schneider, J. What does risperidone add to parent training and stimulant for severe aggression in child attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder? J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2014, 53, 47–60.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connor, D.F.; McLaughlin, T.J.; Jeffers-Terry, M. Randomized Controlled Pilot Study of Quetiapine in the Treatment of Adolescent Conduct Disorder. J. Child. Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2008, 18, 140–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angold, A.; Costello, E.J.; Erkanli, A. Comorbidity. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 1999, 40, 57–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maughan, B.; Rowe, R.; Messer, J.; Goodman, R.; Meltzer, H. Conduct disorder and oppositional defiant disorder in a national sample: Developmental epidemiology. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 2004, 45, 609–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pliszka, S.R. Comorbidity of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder with psychiatric disorder: An overview. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 1998, 59 (Suppl. 7), 50–58. [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt, T.E.; Arseneault, L.; Jaffee, S.R.; Kim-Cohen, J.; Koenen, K.C.; Odgers, C.L.; Slutske, W.S.; Viding, E. Research review: DSM-V conduct disorder: Research needs for an evidence base. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 2008, 49, 3–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, P.S.; Hinshaw, S.P.; Kraemer, H.C.; Lenora, N.; Newcorn, J.H.; Abikoff, H.B.; March, J.S.; Arnold, L.E.; Cantwell, D.P.; Conners, C.K.; et al. ADHD comorbidity findings from the MTA study: Comparing comorbid subgroups. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2001, 40, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinshaw, S.P. The stigmatization of mental illness in children and parents: Developmental issues, family concerns, and research needs. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 2005, 46, 714–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pescosolido, B.A.; Medina, T.R.; Martin, J.K.; Long, J.S. The “Backbone” of Stigma: Identifying the Global Core of Public Prejudice Associated with Mental Illness. Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103, 853–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).