Comparative Analysis of Cadmium Accumulation in Xerophytic Plants: Implications for Species Selection in Phytoremediation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

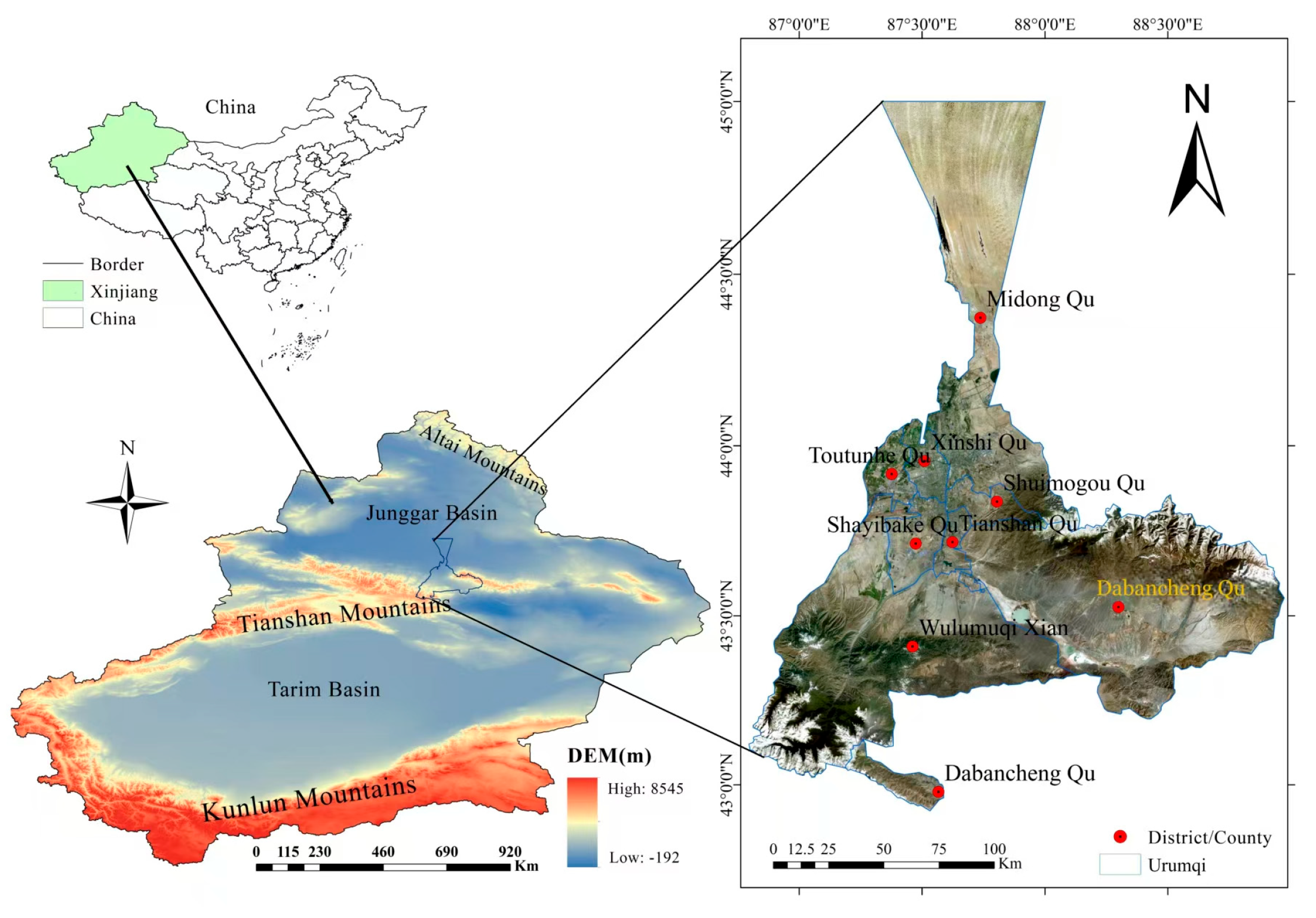

2.1. Setting of Sampling Points

2.2. Collection and Treatments of Soil Samples

2.3. Collection and Processing of Plant Samples

2.4. Classification of Heavy Metal Forms in Samples

2.5. Pollution Assessment in the Study Area

2.6. Data Processing and Analysis

3. Results and Analysis

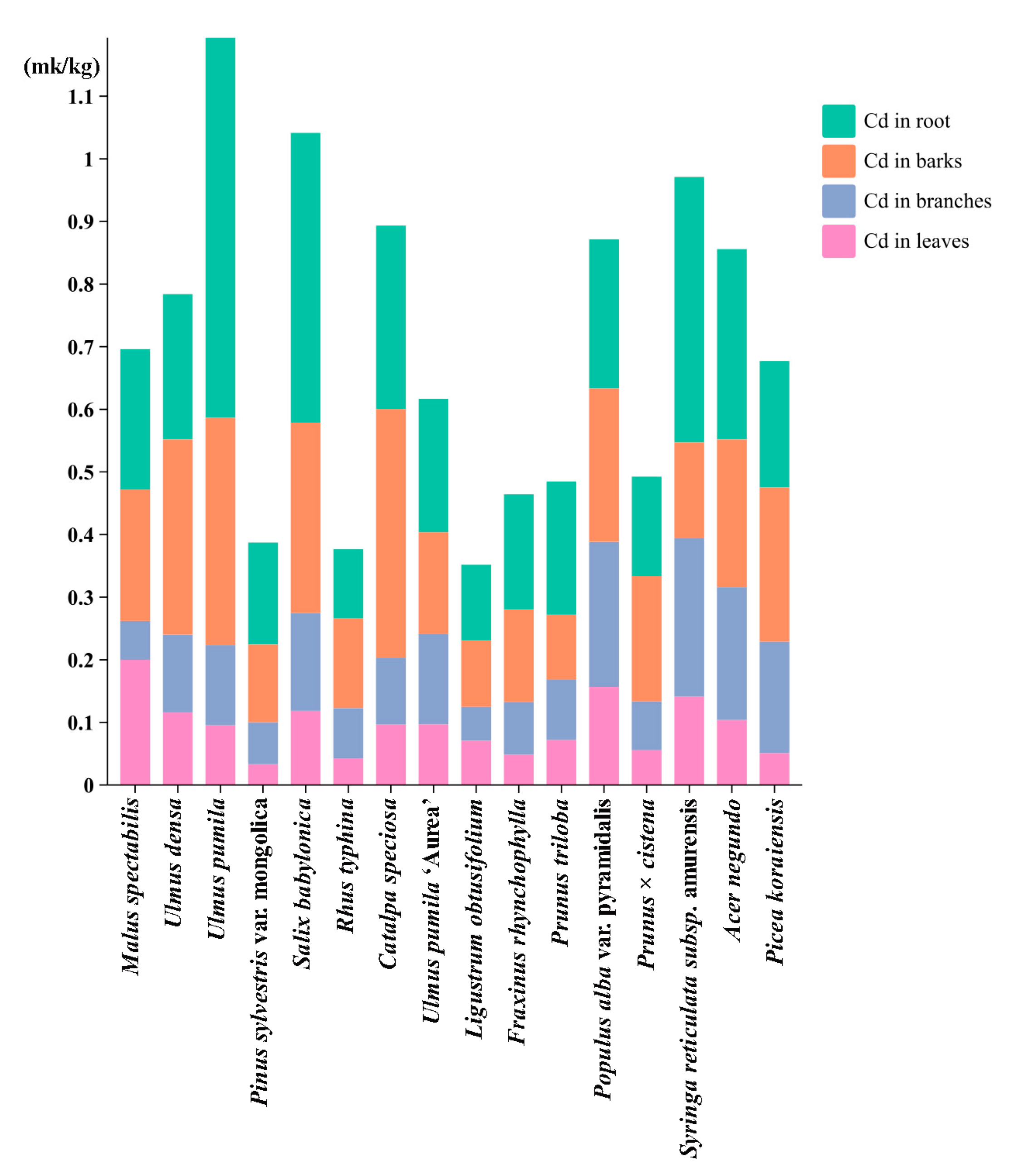

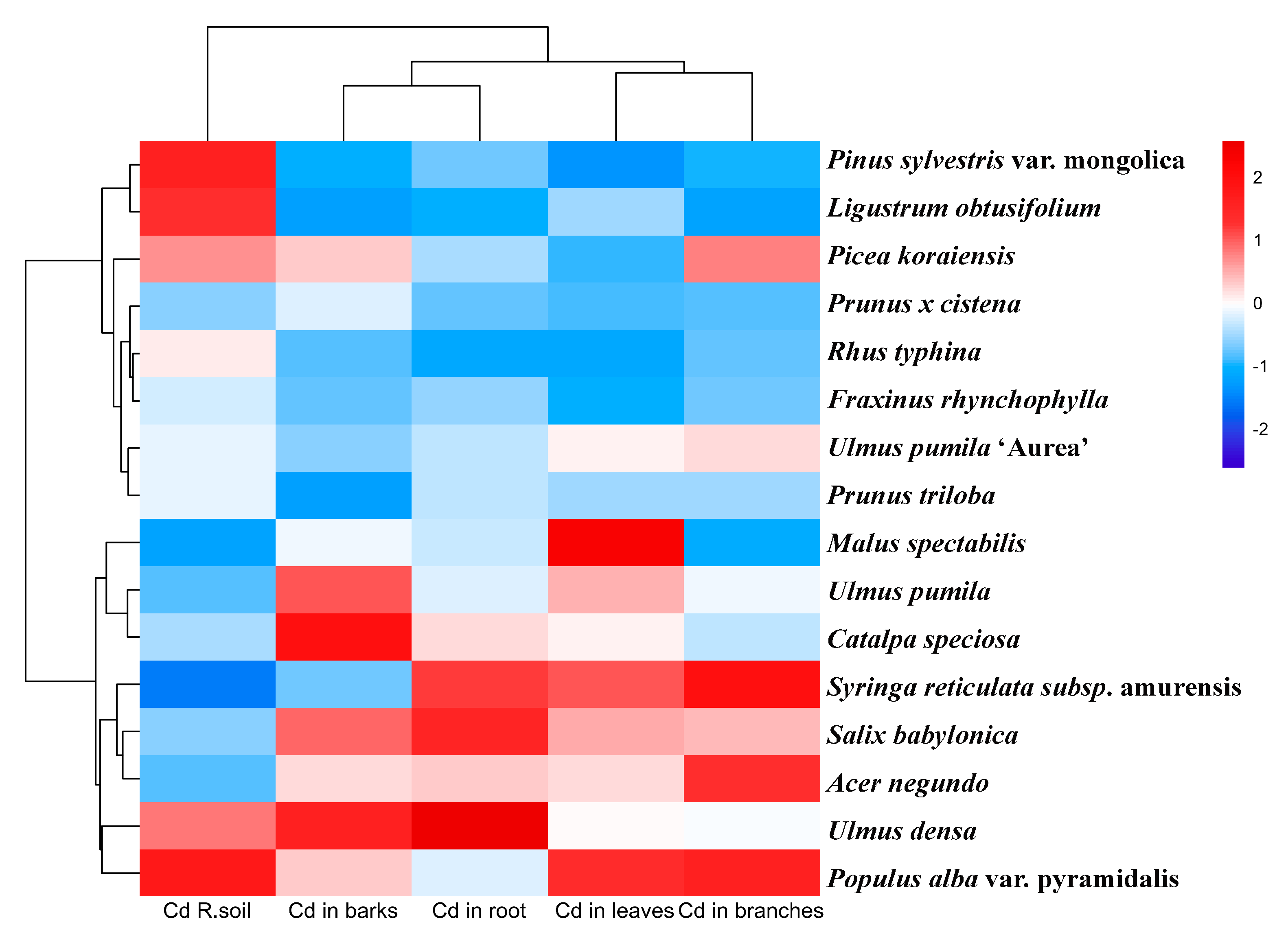

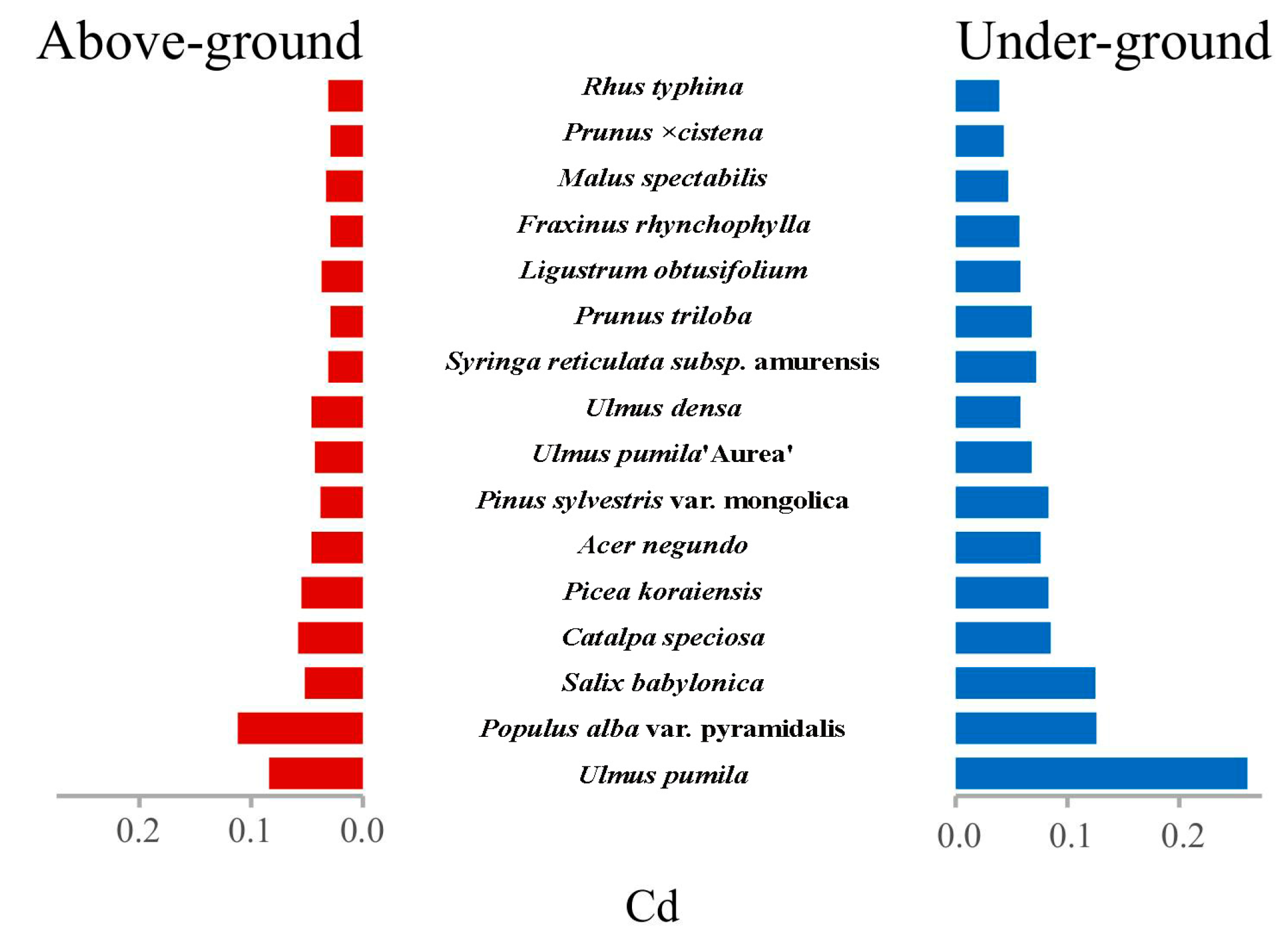

3.1. Integrated Analysis of Cd Accumulation and Translocation Patterns in Woody Plants

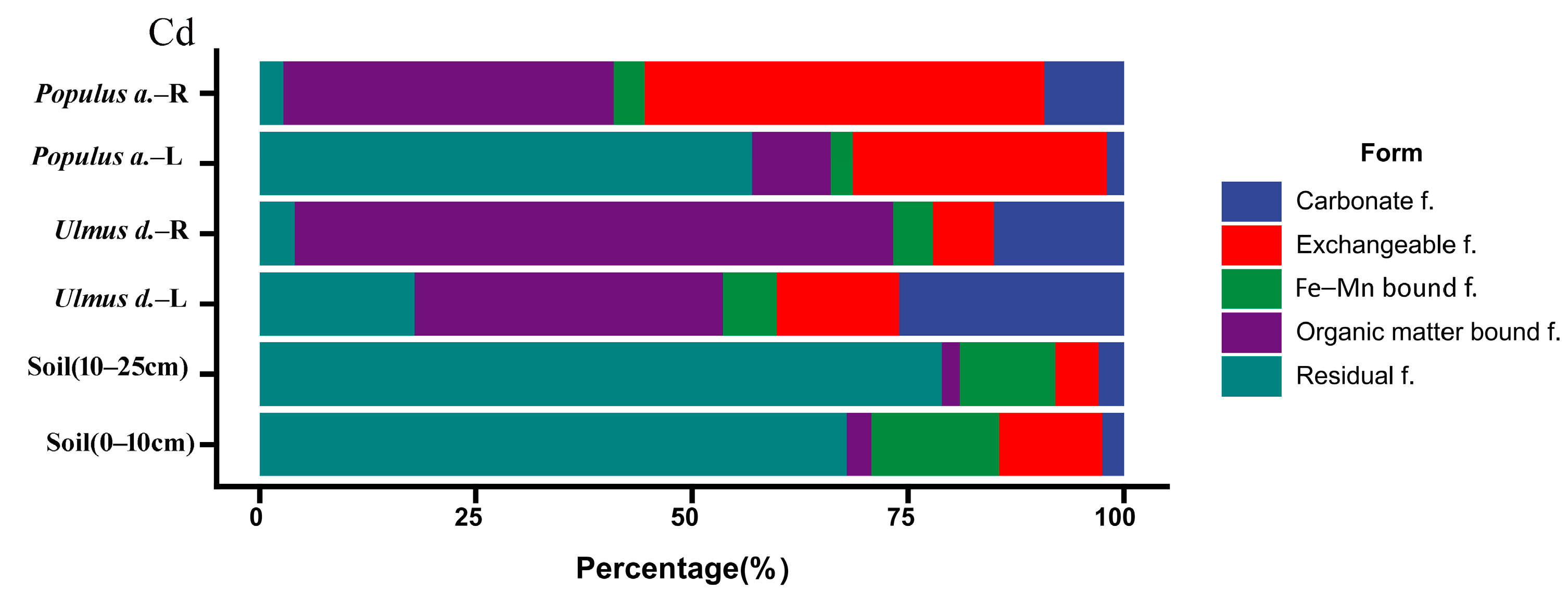

3.2. Interspecific Variation in Cd Speciation Transformation

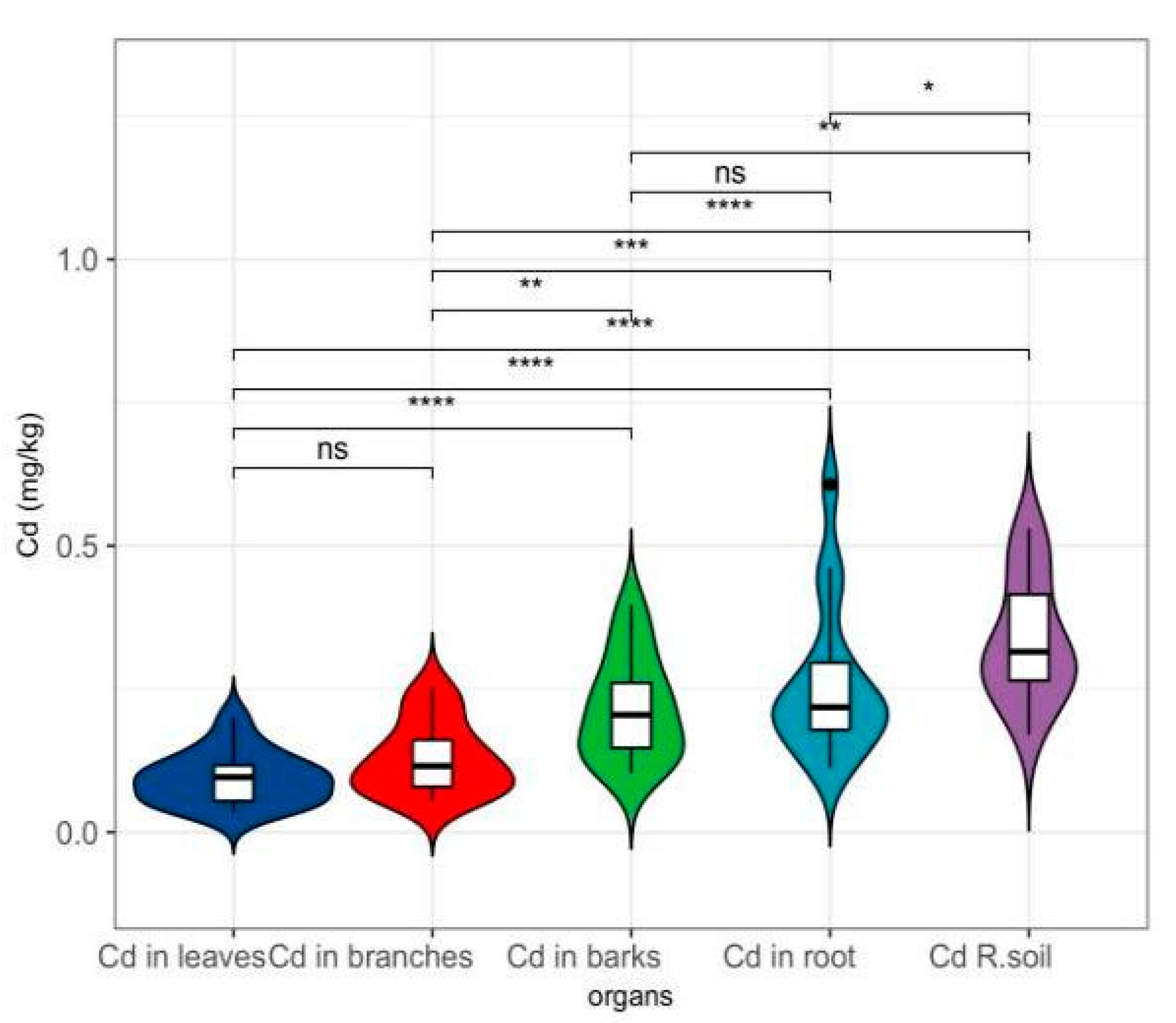

3.3. Compartment-Specific Dynamics of Cd Partitioning: Phytoaccumulation Gradients

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sheng, D.; Meng, X.; Wen, X.; Wu, J.; Yu, H.; Wu, M. Contamination Characteristics, Source Identification, and Source-Specific Health Risks of Heavy Metal(loid)s in Groundwater of An Arid Oasis Region in Northwest China. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 841, 156733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.T.; Gao, Y.; Chen, W.; Zhang, W.; Lu, X. Shifts in Bacterial Diversity, Interactions and Microbial Elemental Cycling Genes Under Cadmium Contamination in Paddy Soil: Implications for Altered Ecological Function. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 461, 132775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karademir, A.; Arpaz, E.; Dogruparmak, S.C.; Ozgul, G. Ambient Air VOC Levels in an Industrial Area of Turkey: Levels, Spatial Distribution, and Health Risk Assessment. Toxics 2025, 13, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, M.R.; Stewart, B.A. Structure and Organic Matter Storage in Agricultural Soils; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gleason, K.E.; Bradford, J.B.; Bottero, A.; D’Amato, A.W.; Fraver, S.; Palik, B.J.; Battaglia, M.A.; Iverson, L.; Kenefic, L.; Kern, C.C. Competition Amplifies Drought Stress in Forests Across Broad Climatic and Compositional Gradients. Ecosphere 2017, 8, e01849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.B.; Sun, G.; Xu, Y.; Liu, W.; Liang, X.; Wang, L. Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Sepiolite, Bentonite, and Phosphate Amendments on the Stabilization Remediation of Cadmium-Contaminated Soils. J. Environ. Manag. 2015, 166, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Wang, C.; Wang, X.; Huo, Z.; Liu, J. Growing Season Water and Salt Migration Between Abandoned Lands and Adjacent Croplands in Arid and Semi-Arid Irrigation Areas in Shallow Water Table Environments. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 274, 107968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baidourela, A.; Liu, L.; Zhayimu, K.; Sun, Q.; Li, L.; Wang, Y. Distribution characteristics and correlation of heavy metals in soil and total suspended particles of Urumqi City. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 19, 4947–4958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohlgemuth, P.M.; Lilley, K.A. Sediment Delivery, Flood Control, and Physical Ecosystem Services in Southern California Chaparral Landscapes. In Valuing Chaparral; Underwood, E., Safford, H., Molinari, N., Keeley, J., Eds.; Springer Series on Environmental Management; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 171–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.X.; Zhao, W.Z.; Liu, H. Ecosystem Regime Shifts and Its Application Prospects to Ecosystem Management in Cold and Arid Regions. Ying Yong Sheng Tai Xue Bao 2024, 35, 1997–2005. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, F.; Wang, X.; Fan, W.; Hong, X.; Hu, S. Assessment of potential health risk for arsenic and heavy metals in some herbal flowers and their infusions consumed in China. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2013, 185, 3909–3916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.K.; Wells, M.; Niazi, N.K.; Bolan, N.; Shaheen, S.; Hou, D.; Gao, B.; Wang, H.; Rinklebe, J.; Wang, Z. Nanobiochar-Rhizosphere Interactions: Implications for The Remediation of Heavy-Metal Contaminated Soils. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 299, 118810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Z.P.; Yin, W.; Wang, Y.; Zeng, W.; Peng, H.; Liang, Y. Silicon-phosphorus pathway mitigates heavy metal stress by buffering rhizosphere acidification. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 904, 166887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Jiang, Y.; Peng, Y.; Chen, X.; Yan, W.; Liang, X.; Wu, Q.; Fang, J. Influence of Miscanthus floridulus on Heavy Metal Distribution and Phytoremediation in Coal Gangue Dump Soils: Implications for Ecological Risk Mitigation. Plants 2025, 14, 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burger, J.; Gochfeld, M.; Bunn, A.; Downs, J.; Jeitner, C.; Pittfield, T.; Salisbury, J. Functional Remediation Components: A Conceptual Method of Evaluating the Effects of Remediation on Risks to Ecological Receptors. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health A 2016, 79, 957–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradley, E.A.; Lockaby, B.G.; Madere, S.; Bolds, S.; Kalin, L.; Ditchkoff, S.S.; Brown, V.R. Stream Pathogenic Bacteria Levels Rebound Post-Population Control of Wild Pigs. J. Environ. Qual. 2025, 54, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalis, E.J.; Temminghoff, E.J.; Weng, L.; van Riemsdijk, W.H. Effects of humic acid and competing cations on metal uptake by Lolium perenne. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2006, 25, 702–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalis, E.J.; Weng, L.; Dousma, F.; Temminghoff, E.J.; van Riemsdijk, W.H. Measuring Free Metal Ion Concentrations in Situ in Natural Waters Using the Donnan Membrane Technique. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2006, 40, 955–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baidourela, A.; Wen, H.; Cai, L.; Sun, Q.; Li, L.; Kahaer, Z.; Nurmamat, K.; Wang, Y. The propensity for heavy metal accumulation in Ulmus pumila L. and its relationship with rhizosphere soil and total suspended particles in Urumqi, Northwest China. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 380, 126567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.L. Study on the Enrichment Characteristics of Heavy Metals in Five Common Tree Species in Different Functional Areas of Beijing. Ph.D. Thesis, Chinese Academy of Forestry, Beijing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- HJ 491-2019; Soil and Sediment—Determination of Copper, Zinc, Lead, Nickel and Chromium—Flame Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometry. Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2019.

- Cao, S.; Wang, W.; Wang, F.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Z.; Li, R.; Yang, S. Drought-tolerant Streptomyces pactum Act12 assist phytoremediation of cadmium-contaminated soil by Amaranthus hypochondriacus: Great potential application in arid/semi-arid areas. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 14898–14907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessier, A.; Campbell, P.G.C.; Bisson, M. Sequential extraction procedure for the speciation of particulate trace metals. Anal. Chem. 1979, 51, 844–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.F.; Bai, Y.X.; Gai, S.N. Single-Factor and Nemerow Multi-Factor Index to Assess Heavy Metals Contamination in Soils on Railway Side of Harbin-Suifenhe Railway in Northeastern China. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2011, 71–78, 3033–3036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, M.; Li, Y.; Yang, J.; Lei, K.; Li, Y.; Li, F.; Zheng, D.; Fang, X.; Cao, Y. Heavy Metal Contamination Risk Assessment and Correlation Analysis of Heavy Metal Contents in Soil and Crops. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 278, 116911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abudujapaer, A. Characteristics of Soil Heavy Metal Pollution and Health Risk Assessment in Zhundong Area. Master’s Thesis, Xinjiang University, Urumqi, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.X.; Song, B. Heavy metal enrichment characteristics and application potential of dominant plants in the Lanping lead-zinc mining area, Yunnan Province. Environ. Sci. 2020, 41, 334–341. [Google Scholar]

- Sulaiman, F.R.; Hamzah, H.A. Heavy Metals Accumulation in Suburban Roadside Plants of a Tropical Area (Jengka, Malaysia). Ecol. Process. 2018, 7, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, S.Y.; Goh, H.W.; Mohd, M.F.B.; Haris, H.; Azizan, N.A.; Zakaria, N.A.; Johar, Z. Heavy Metals Removal from Domestic Sewage in Batch Mesocosm Constructed Wetlands using Tropical Wetland Plants. Water 2023, 15, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.; Du, L.; Johnson, M.; McCullough, B.D. Comparing Programming Languages for Data Analytics: Accuracy of Estimation in Python and R. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2024, 14, e1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siebert, J.; Groß, J.; Schroth, C. A Systematic Review of Packages for Time Series Analysis. Eng. Proc. 2021, 5, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, T.T.; Leveque, T.; Austruy, A.; Goix, S.; Schreck, E.; Dappe, V.; Sobanska, S.; Foucault, Y.; Dumat, C. Foliar Uptake and Metal(loid) Bioaccessibility in Vegetables Exposed to Particulate Matter. Environ. Geochem. Health 2014, 36, 897–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, M.; Dumat, C.; Khalid, S.; Schreck, E.; Xiong, T.; Niazi, N.K. Foliar Heavy Metal Uptake, Toxicity and Detoxification in Plants: A Comparison of Foliar and Root Metal Uptake. J. Hazard. Mater. 2017, 325, 36–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Li, F.; Luo, C.; Liu, X.; Wang, S.; Liu, T.; Li, X. Foliar Application of Two Silica Sols Reduced Cadmium Accumulation in Rice Grains. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 161, 1466–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajpai, R.; Mishra, G.; Mohabe, S.; Upreti, D.K.; Nayaka, S. Determination of Atmospheric Heavy Metals Using Two Lichen Species in Katni and Rewa Cities, India. J. Environ. Biol. 2011, 32, 195–199. [Google Scholar]

- Lequy, E.; Sauvage, S.; Laffray, X.; Gombert-Courvoisier, S.; Pascaud, A.; Galsomiès, L.; Leblond, S. Assessment of the Uncertainty of Trace Metal and Nitrogen Concentrations in Mosses Due to Sampling, Sample Preparation and Chemical Analysis Based on the French Contribution to ICP-Vegetation. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 71, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salo, H.; Bucko, M.S.; Vaahtovuo, E.; Limo, J.; Mäkinen, J.; Pesonen, L.J. Biomonitoring of Air Pollution in SW Finland by Magnetic and Chemical Measurements of Moss Bags and Lichens. J. Geochem. Explor. 2012, 115, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, S. Calcium Carbonate Impact on Pb and Cd Distribution in the Nile Floodplain Soil and Soil Quality Modeling. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2025, 11, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbdElgawad, H.; Zinta, G.; Hamed, B.A.; Selim, S.; Beemster, G.; Hozzein, W.N.; Wadaan, M.A.M.; Asard, H.; Abuelsoud, W. Maize Roots and Shoots Show Distinct Profiles of Oxidative Stress and Antioxidant Defense Under Heavy Metal Toxicity. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 258, 113705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, T.; Jiang, T.; Yang, K.; Li, J.; Liang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Gao, N.; Li, H.; Lu, W.; Cui, K. Biomonitoring of Heavy Metal Contamination with Roadside Trees from Metropolitan Area of Hefei, China. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2021, 193, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghio, A.J.; Cohen, M.D. Disruption of Iron Homeostasis as a Mechanism of Biologic Effect by Ambient Air Pollution Particles. Inhal. Toxicol. 2005, 17, 709–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, A.; Agrawal, M. Use of GLM Approach to Assess the Responses of Tropical Trees to Urban Air Pollution in Relation to Leaf Functional Traits and Tree Characteristics. Ecotoxicology 2018, 152, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.W.; Cho, K.S.; Moberly, J.G.; Roh, Y.; Phelps, T.J. Simultaneous Leaching and Carbon Sequestration in Constrained Aqueous Solutions. Environ. Geochem. Health 2011, 33, 543–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šimůnek, J.; Hopmans, J.W. Modeling Compensated Root Water and Nutrient Uptake. Ecol. Model. 2009, 220, 505–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.F.; Li, Y.W.; Zou, L.J.; Liu, B.L.; Xiang, L.; Zhao, H.M.; Li, H.; Cai, Q.Y.; Hou, X.W.; Mo, C.H.; et al. Variety-Selective Rhizospheric Activation, Uptake, and Subcellular Distribution of Perfluorooctanesulfonate (PFOS) in Lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.). Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 8730–8741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushwaha, A.; Rani, R.; Kumar, S.; Gautam, A. Heavy Metal Detoxification and Tolerance Mechanisms in Plants: Implications for Phytoremediation. Environ. Rev. 2016, 24, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nzunzu, J.L.; Nsimba, M.M.; Nkanga, C.I.; Lami, M.; Matadi, J.M. Phytochemical Profile of An Anti-Sickling Fraction from The Trunk Bark and Branches of Ceiba Pentandra. Phytomedicine Plus 2022, 2, 100352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilek, A.; Van Stan, J.T.; Morkisz, K.; Kucza, J. Vertical Variability in Bark Hydrology for Two Coniferous Tree Species. Front. For. Glob. Change 2021, 4, 687907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Mara, K.; Adams, M.; Burford, M.A.; Fry, B.; Cresswell, T. Uptake and Accumulation of Cadmium, Manganese and Zinc by Fisheries Species: Trophic Differences in Sensitivity to Environmental Metal Accumulation. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 690, 867–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballikaya, P.; Brunner, I.; Cocozza, C.; Grolimund, D.; Kaegi, R.; Murazzi, M.E.; Schaub, M.; Schönbeck, L.C.; Sinnet, B.; Cherubini, P. First Evidence of Nanoparticle Uptake Through Leaves and Roots in Beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) and Pine (Pinus sylvestris L.). Tree Physiol. 2022, 42, 2051–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z. Modeling Plant Uptake of Organic Contaminants by Root Vegetables: The Role of Diffusion, Xylem, and Phloem Uptake Routes. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 434, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, V.A.M.; da Costa, F.V.; de Araújo, F.V.; Alencar, B.T.B.; Ribeiro, V.H.V.; Okumura, F.; Simeone, M.L.F.; Dos Santos, J.B. Phytoremediation of Brazilian Tree Species in Soils Contaminated by Herbicides. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 27561–27568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| The Name of the Plant | The Average Tree Height H/m | Diameter at Breast Height D/cm | The Crown m |

|---|---|---|---|

| Malus spectabilis | 5.43 ± 0.21 | 17.50 ± 0.41 | 5.20 × 5.70 |

| Ulmus pumila | 12.67 ± 1.25 | 18.50 ± 1.08 | 5.40 × 6.50 |

| Ulmus densa | 6.90 ± 0.41 | 16.17 ± 1.03 | 6.20 × 6.80 |

| Pinus sylvestris var. mongolica | 8.53 ± 0.82 | 13.33 ± 1.25 | 7.40 × 5.80 |

| Salix babylonica | 8.87 ± 0.39 | 25.67 ± 1.25 | 6.80 × 7.10 |

| Rhus typhina | 6.00 ± 0.51 | 11.57 ± 0.42 | 3.30 × 4.60 |

| Catalpa speciosa | 7.93 ± 0.50 | 13.67 ± 1.25 | 4.30 × 4.70 |

| Ulmus pumila ‘Aurea’ | 6.33 ± 0.46 | 13.00 ± 0.82 | 3.50 × 4.60 |

| Ligustrum obtusifolium | 0.80 ± 0.29 | / | / |

| Fraxinus rhynchophylla | 7.90 ± 0.37 | 11.33 ± 1.26 | 4.50 × 5.80 |

| Prunus triloba | 1.10 ± 0.29 | / | / |

| Populus alba var. pyramidalis | 16.47 ± 1.13 | 18.33 ± 1.24 | 4.20 × 4.80 |

| Prunus × cistena | 1.20 ± 0.33 | / | / |

| Syringa reticulata subsp. amurensis | 7.73 ± 0.26 | 16.00 ± 0.82 | 3.50 × 4.40 |

| Acer negundo | 8.50 ± 0.65 | 16.13 ± 0.84 | 4.60 × 5.40 |

| Picea koraiensis | 5.67 ± 0.25 | 11.40 ± 0.98 | 3.70 × 4.60 |

| Metal | Adsorption or Bio-Accumulation Status | Concentration(mg/kg) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cd | Spinach | 317.3 | [32,33] |

| Cd | Rice | 30.1 | [34] |

| Cd | Lettuce | 1.7 | [32] |

| Cd | Pyxine cocoes | 16.9 | [35] |

| Cd | Thuidium tamariscinum | 0.44 | [36] |

| Cd | Sphagnum papillosum | 4.31 | [37] |

| Cd | Soil in Egypt | 7.84 | [38] |

| Cd | Ulmus densa | 0.36 | Urumqi, in this article |

| Cd | Ligustrum obtusifolium | 0.08 | Urumqi, in this article |

| Cd | Soil | 0.34 | Urumqi, in this article |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yusuyin, Y.; Baidourela, A.; Xiaokelati, J.; Wen, H.; Zhayimu, K.; Sun, Q.; Sun, G.; Ma, F. Comparative Analysis of Cadmium Accumulation in Xerophytic Plants: Implications for Species Selection in Phytoremediation. Toxics 2026, 14, 135. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14020135

Yusuyin Y, Baidourela A, Xiaokelati J, Wen H, Zhayimu K, Sun Q, Sun G, Ma F. Comparative Analysis of Cadmium Accumulation in Xerophytic Plants: Implications for Species Selection in Phytoremediation. Toxics. 2026; 14(2):135. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14020135

Chicago/Turabian StyleYusuyin, Yusufujiang, Aliya Baidourela, Julati Xiaokelati, Huihui Wen, Kahaer Zhayimu, Qian Sun, Guili Sun, and Fuxiang Ma. 2026. "Comparative Analysis of Cadmium Accumulation in Xerophytic Plants: Implications for Species Selection in Phytoremediation" Toxics 14, no. 2: 135. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14020135

APA StyleYusuyin, Y., Baidourela, A., Xiaokelati, J., Wen, H., Zhayimu, K., Sun, Q., Sun, G., & Ma, F. (2026). Comparative Analysis of Cadmium Accumulation in Xerophytic Plants: Implications for Species Selection in Phytoremediation. Toxics, 14(2), 135. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14020135