Size- and Time-Dependent Effects of Polyethylene Microplastics on Soil Nematode Communities: A 360-Day Field Experiment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Processing and Sampling

2.3. Soil Nematode Extraction and Identification

2.4. Soil Physicochemical Analysis

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

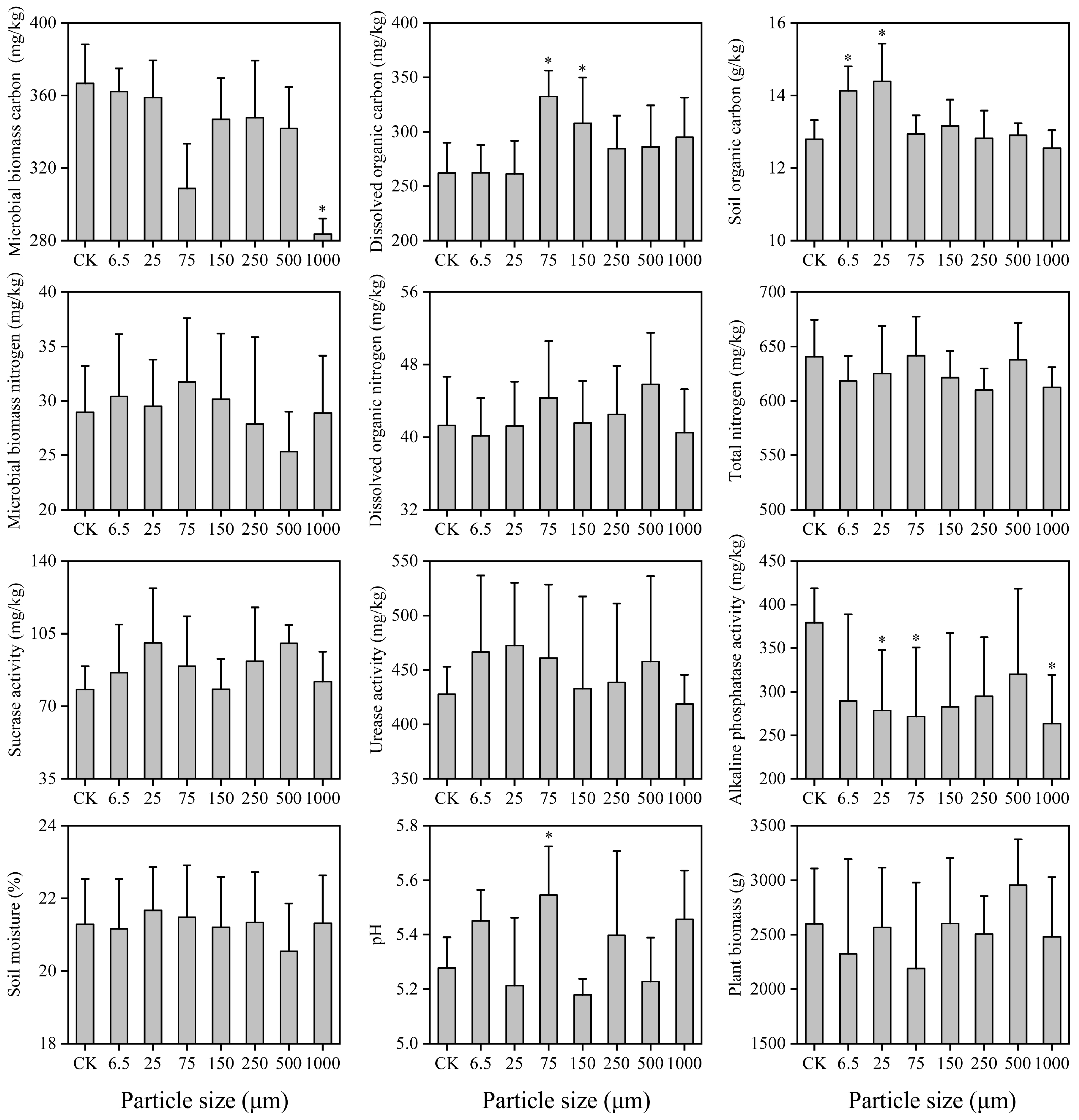

3.1. Soil Properties

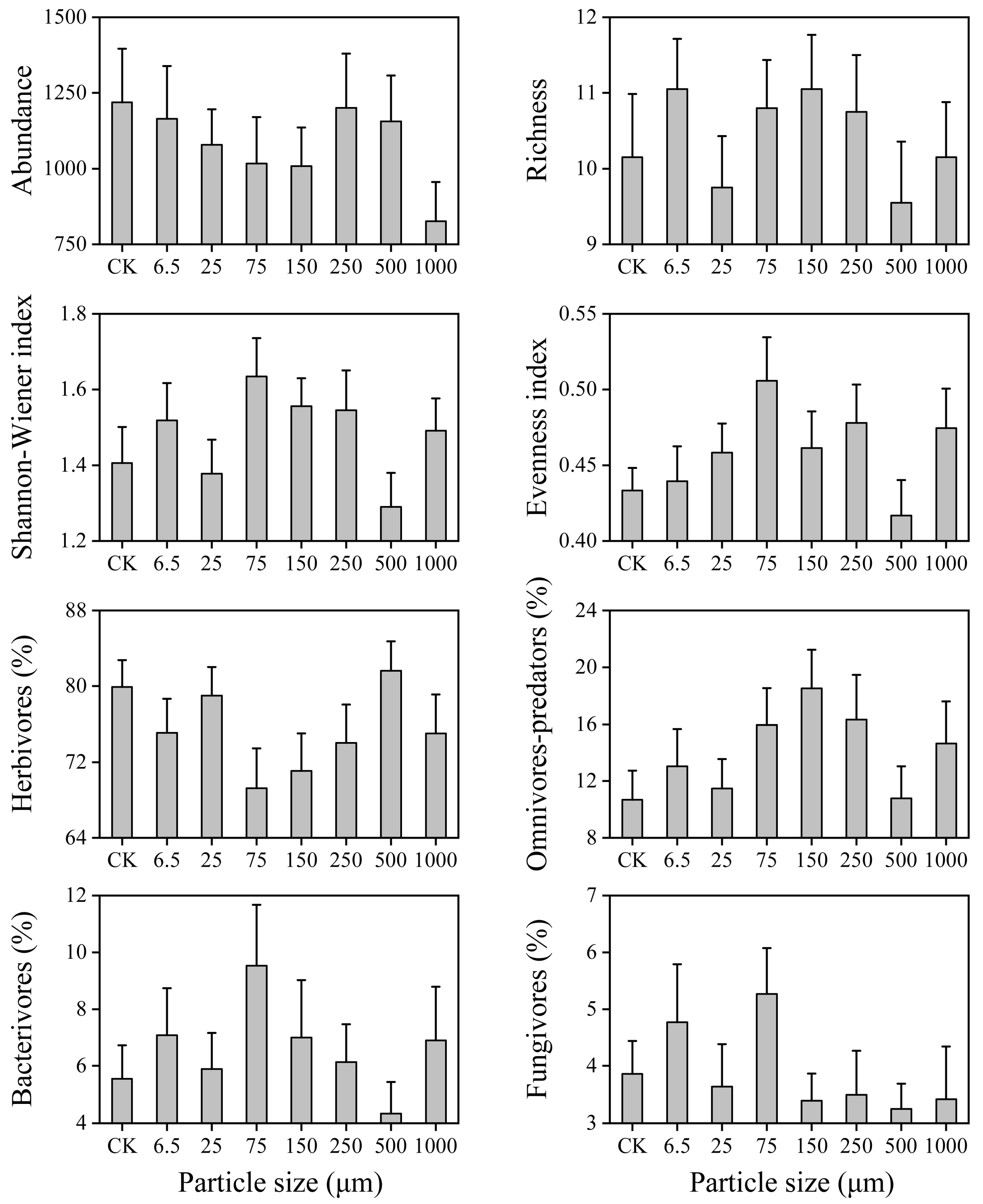

3.2. Soil Nematode Community Composition

3.3. Soil Nematode Community Structure

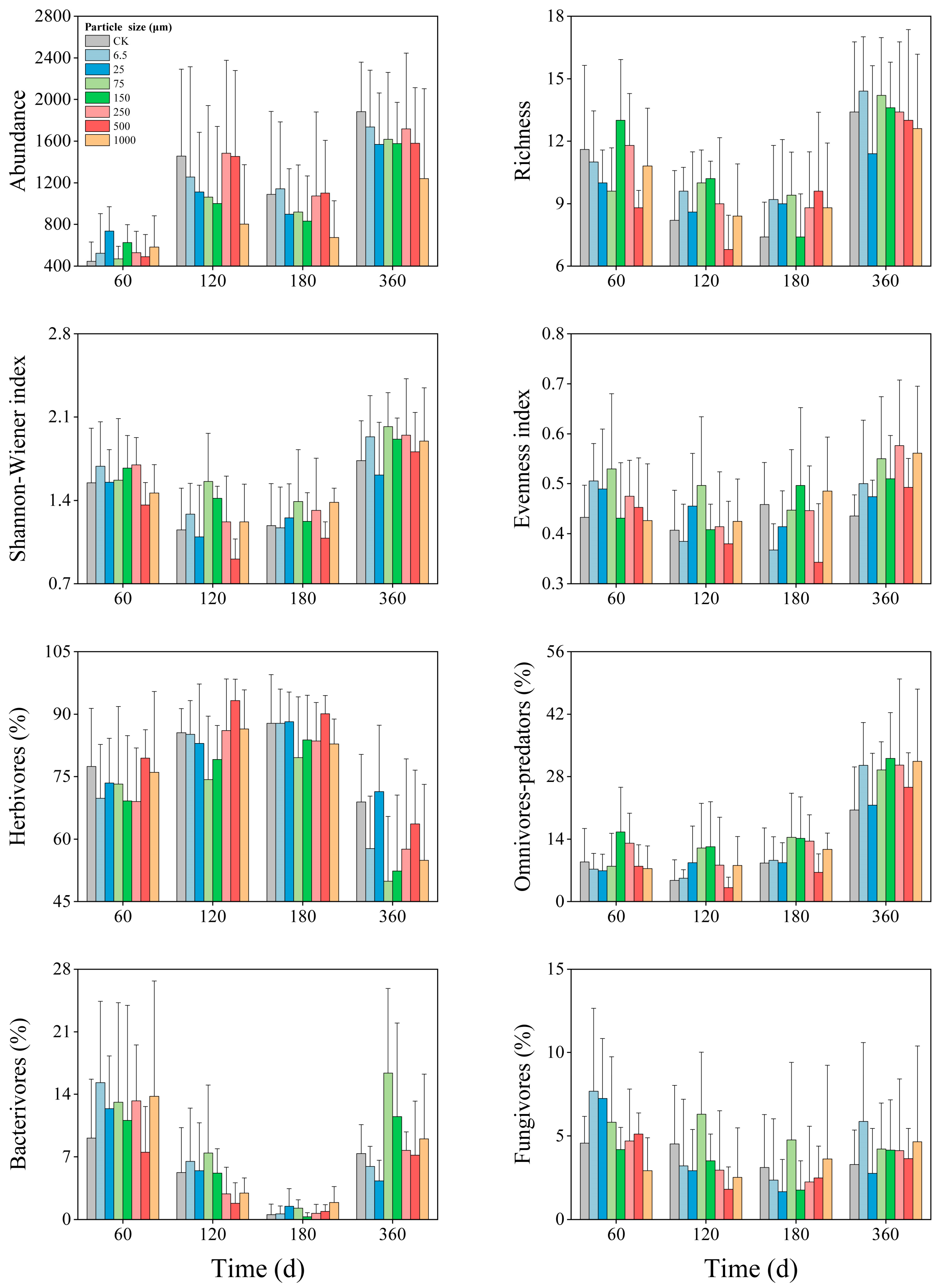

3.4. Temporal Dynamics

3.5. Relationships Between Environmental Factors and Soil Nematodes

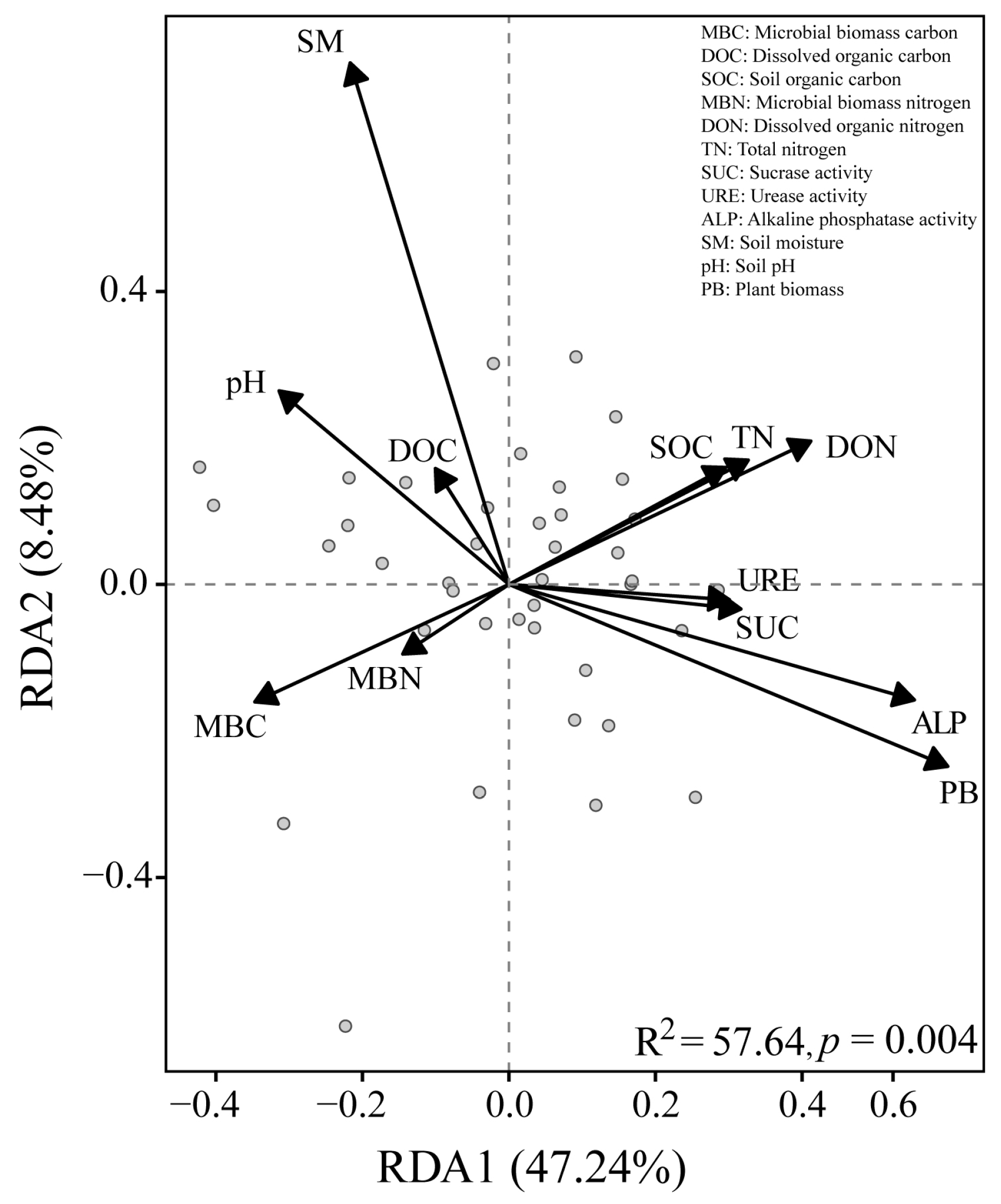

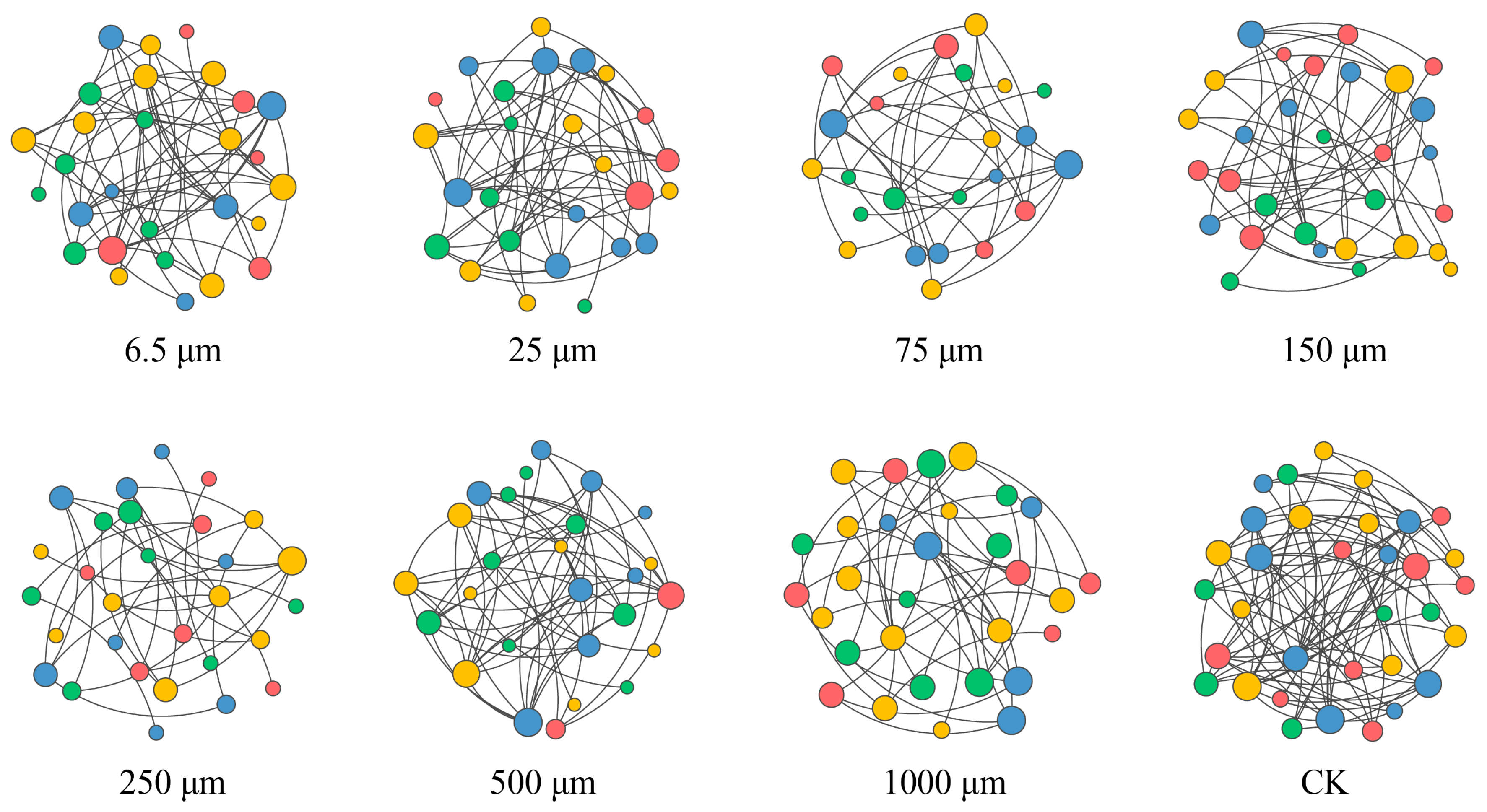

3.6. Nematodes Co-Occurrence Network Analysis

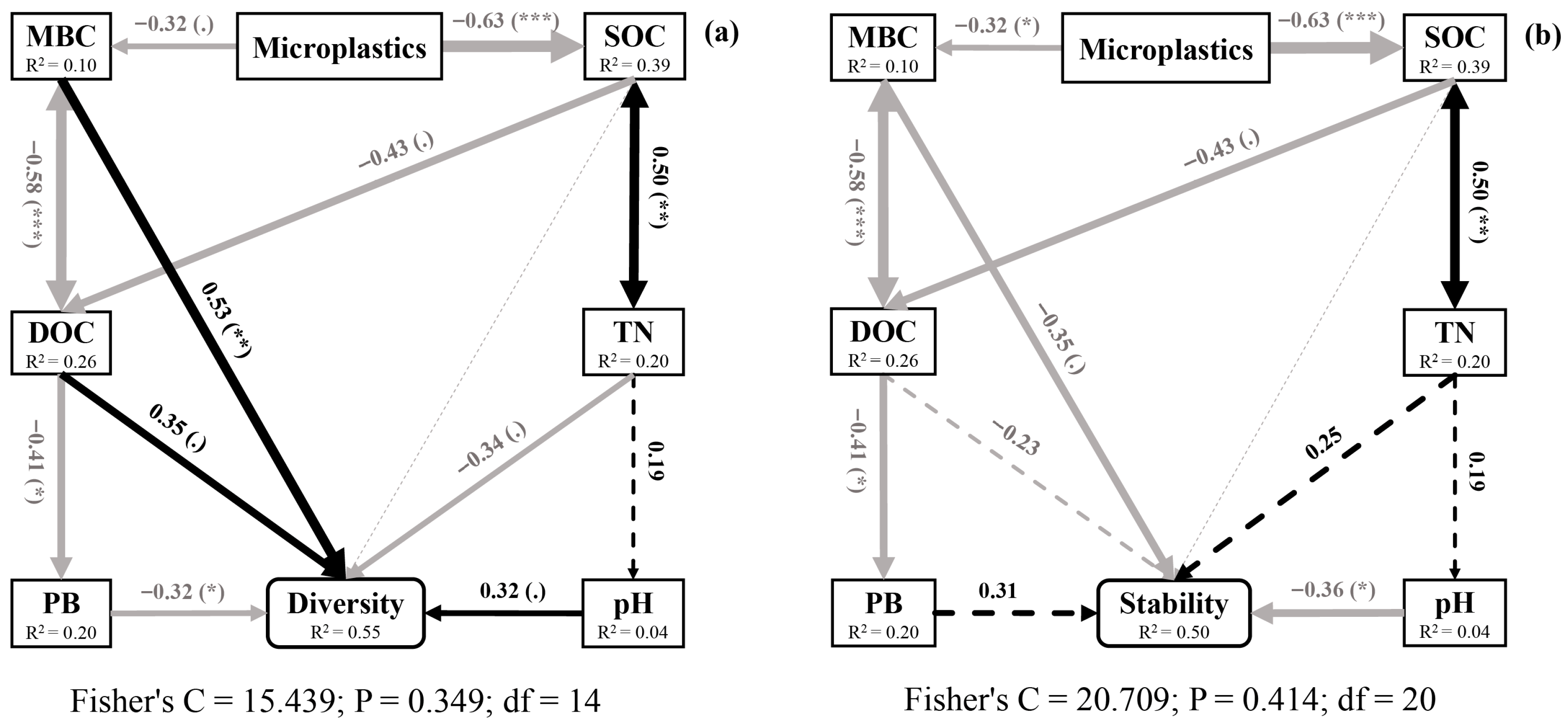

3.7. Effects of Microplastics on Nematode Diversity and Stability

4. Discussion

4.1. Microplastics Reshaped Soil Nematode Community Structure

4.2. The Effect of Microplastics on Soil Nematodes Depended on Particle Size

4.3. Pathways of Microplastics Affected Soil Nematode Communities

4.4. Effect of Microplastics on Soil Nematodes Depended on Exposure Time

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- MacLeod, M.; Arp, H.P.H.; Tekman, M.B.; Jahnke, A. The global threat from plastic pollution. Science 2021, 373, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, R.C.; Courtene-Jones, W.; Boucher, J.; Pahl, S.; Raubenheimer, K.; Koelmans, A.A. Twenty years of microplastic pollution research-what have we learned? Science 2024, 386, eadl2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Mishra, S.; Pandey, R.; Yu, Z.G.; Kumar, M.; Khoo, K.S.; Thakur, T.K.; Show, P.L. Microplastics in terrestrial ecosystems: Un-ignorable impacts on soil characterises, nutrient storage and its cycling. Trends Anal. Chem. 2023, 158, 116869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.W.; Waldman, W.R.; Kim, T.Y.; Rillig, M.C. Effects of different microplastics on nematodes in the soil environment: Tracking the extractable additives using an ecotoxicological approach. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 13868–13878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fueser, H.; Mueller, M.T.; Traunspurger, W. Rapid ingestion and egestion of spherical microplastics by bacteria-feeding nematodes. Chemosphere 2020, 261, 128162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Adams, C.A.; Wang, F.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, S. Interactions between microplastics and soil fauna: A critical review. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 52, 3211–3243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Cai, C.; Gu, Y.; Shi, Y.; Gao, X. Microplastics in plant-soil ecosystems: A meta-analysis. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 308, 119718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Yumeng, Y.; Yu, Y.; Yinglin, H.; Fu, B.; Wang, J. Distribution, sources, migration, influence and analytical methods of microplastics in soil ecosystems. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 243, 114009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Jin, T.; Zou, T.; Xu, L.; Xi, B.; Xu, D.; He, J.; Xiong, L.; Tang, C.; Peng, J. Current progress on plastic/microplastic degradation: Fact influences and mechanism. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 304, 119159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onink, V.; Kaandorp, M.L.A.; van Sebille, E.; Laufkötter, C. Influence of particle size and fragmentation on large-scale microplastic transport in the Mediterranean Sea. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 15528–15540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.W.; An, Y.-J. Edible size of polyethylene microplastics and their effects on springtail behavior. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 266, 115255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Yang, Y.; Yu, Y. Size effects of polystyrene microplastics on the accumulation and toxicity of (semi-)metals in earthworms. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 291, 118194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, M.-T.; Fueser, H.; Höss, S.; Traunspurger, W. Species-specific effects of long-term microplastic exposure on the population growth of nematodes, with a focus on microplastic ingestion. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 118, 106698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shao, H.; Liu, J.; Cao, R.; Shang, E.; Liu, S.; Li, Y. Transport and transformation of microplastics and nanoplastics in the soil environment: A critical review. Soil Use Manag. 2021, 37, 224–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebteoui, K.; Csabai, Z.; Stanković, J.; Baranov, V.; Jovanović, B.; Milošević, D. Downsizing plastics, upsizing impact: How microplastic particle size affects Chironomus riparius bioturbation activity. Environ. Res. 2025, 270, 121055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdolahpur Monikh, F.; Chupani, L.; Vijver, M.G.; Peijnenburg, W.J.G.M. Parental and trophic transfer of nanoscale plastic debris in an assembled aquatic food chain as a function of particle size. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 269, 116066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimek, B.; Grzyb, D.; Łukiewicz, B.; Niklińska, M. Microplastics increase soil respiration rate, decrease soil mesofauna feeding activity and change enchytraeid body length distribution in three contrasting soils. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2024, 201, 105463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, D.C.; Geisen, S.; Wall, D.H. Soil fauna: Occurrence, biodiversity, and roles in ecosystem function. In Soil Microbiology, Ecology and Biochemistry, 5th ed.; Paul, E.A., Frey, S.D., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 131–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Feng, J.; Shen, Y.; Zhu, B. Microplastics effects on soil biota are dependent on their properties: A meta-analysis. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2023, 178, 108940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; Yang, G.; Dou, P.; Qian, S.; Zhao, L.; Yang, Y.; Fanin, N. Microplastics negatively affect soil fauna but stimulate microbial activity: Insights from a field-based microplastic addition experiment. Proc. R. Soc. Biol. Sci. 2020, 287, 20201268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, C.; Lin, X.; Li, P.; Hou, J.; Yang, M.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, S.; Yang, K.; Lin, D. Nematode uptake preference toward different nanoplastics through avoidance behavior regulation. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 11323–11334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adhikari, K.; Astner, A.F.; DeBruyn, J.M.; Yu, Y.; Hayes, D.G.; O’Callahan, B.T.; Flury, M. Earthworms exposed to polyethylene and biodegradable microplastics in soil: Microplastic characterization and microbial community analysis. ACS Agric. Sci. Technol. 2023, 3, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.-Y.; Li, B.; Jia, Q.-P.; Li, X.; Zhao, Q.; Fan, P.-D.; Wang, C.-Q.; Zhang, L.-Y. Neglected microplastics and their risks in rivers throughout the Three Gorges Reservoir Area. Toxics 2025, 13, 781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sang, J.; Hou, B.; Wang, H.; Ding, X. Prediction of water resources change trend in the Three Gorges Reservoir Area under future climate change. J. Hydrol. 2023, 617, 128881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, W.R. A rapid centrifugal-flotation technique for separating nematodes from soil. Plant Dis. Reptr. 1964, 48, 692. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Liang, W.; Li, Q. Morphological Classification and Distribution Patterns of Soil Nematodes in Forests of Changbai Mountain, China; China Agriculture Press: Beijing, China, 2013; pp. 1–174. [Google Scholar]

- Yeates, G.W.; Bongers, T.; De Goede, R.G.M.; Freckman, D.W.; Georgieva, S.S. Feeding habits in soil nematode families and genera-an outline for soil ecologists. J. Nematol. 1993, 25, 315–331. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Liu, Y.; Ma, L. Effective factors of urease activities in soil by using the phenol-sodium hypochlorite colorimetric method. China. J. Soil Sci. 2019, 50, 1166–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankeberger, W.T.; Johanson, J.B. Method of measuring invertase activity in soils. Plant Soil 1983, 74, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadem, A.; Raiesi, F. Response of soil alkaline phosphatase to biochar amendments: Changes in kinetic and thermodynamic characteristics. Geoderma 2019, 337, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.J. Permutation tests for univariate or multivariate analysis of variance and regression. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2001, 58, 626–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, P. VEGAN, a package of R functions for community ecology. J. Veg. Sci. 2003, 14, 927–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccaletti, S.; Latora, V.; Moreno, Y.; Chávez, M.; Hwang, D.-U. Complex networks: Structure and dynamics. Phys. Rep. 2006, 424, 175–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamini, Y.; Hochberg, Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. B 1995, 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Horvath, S. Understanding network concepts in modules. BMC Syst. Biol. 2007, 1, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herren, C.M.; McMahon, K.D. Cohesion: A method for quantifying the connectivity of microbial communities. ISME J. 2017, 11, 2426–2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Chen, X.; Jia, Z.; Zhai, L.; Zhang, B.; Grüters, U.; Ma, S.; Qian, J.; Liu, X.; Zhang, J.; et al. Meta-analysis reveals the effects of microbial inoculants on the biomass and diversity of soil microbial communities. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 8, 1270–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lefcheck, J.S. piecewiseSEM: Piecewise structural equation modelling in R for ecology, evolution, and systematics. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2015, 7, 573–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Li, P.; Entemake, W.; Guo, Z.; Xue, S. Concentration-dependent impacts of microplastics on soil nematode community in bulk soils of maize: Evidence from a pot experiment. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 872898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fueser, H.; Mueller, M.-T.; Weiss, L.; Höss, S.; Traunspurger, W. Ingestion of microplastics by nematodes depends on feeding strategy and buccal cavity size. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 255, 113227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace, H.R. The Dynamics of Nematode Movement. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 1968, 6, 91–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Liu, F.; Cryder, Z.; Huang, D.; Lu, Z.; He, Y.; Wang, H.; Lu, Z.; Brookes, P.C.; Tang, C.; et al. Microplastics in the soil environment: Occurrence, risks, interactions and fate—A review. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 50, 2175–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Wang, C.; Zhu, B. Drought alleviates the negative effects of microplastics on soil micro-food web complexity and stability. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 11206–11217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, L.; Liu, M.; Song, Y.; Lu, S.; Hu, J.; Cao, C.; Xie, B.; Shi, H.; He, D. Polystyrene (nano)microplastics cause size-dependent neurotoxicity, oxidative damage and other adverse effects in Caenorhabditis elegans. Environ. Sci. Nano 2018, 5, 2009–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Cui, H.; Xia, W.; Liu, Z.; Jiang, X.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Chen, S.; Xiao, S. Impact of microplastic concentration on soil nematode communities on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau: Evidence from a field-based microcosms experiment. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 490, 137856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, M.; Jia, W.; Qin, X. LDPE microplastic films alter microbial community composition and enzymatic activities in soil. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 254, 112983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.W.; Liang, Y.; Lozano, Y.M.; Rillig, M.C. Microplastics reduce the negative effects of litter-derived plant secondary metabolites on nematodes in soil. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9, 790560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Hou, X.; Cui, H.; Xiao, S.; Liu, Z.; Chen, J.; Wang, J.; Zhang, A.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.; et al. Long-term plant community removal alters soil nematode communities mainly through the trophic cascading effects of fungal channel. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2023, 23, 6696–6706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, W.; Li, W.; Yang, W.; Jing, S. Effects of microplastics on the water characteristic curve of soils with different textures. Chemosphere 2023, 317, 137762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graf, M.; Greenfield, L.M.; Reay, M.K.; Bargiela, R.; Williams, G.B.; Onyije, C.; Lloyd, C.E.M.; Bull, I.D.; Evershed, R.P.; Golyshin, P.N.; et al. Increasing concentration of pure micro- and macro-LDPE and PP plastic negatively affect crop biomass, nutrient cycling, and microbial biomass. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 458, 131932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavatska, O.; Müller, K.; Butenschoen, O.; Schmalwasser, A.; Kandeler, E.; Scheu, S.; Totsche, K.U.; Ruess, L. Disentangling the root-and detritus-based food chain in the micro-food web of an arable soil by plant removal. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0180264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Chen, G.; Hassan, W.M.; Chen, H.; Li, J.; Du, G. Fertilization influences the nematode community through changing the plant community in the Tibetan Plateau. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2017, 78, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Menzel, R.; Ruess, L. The impact of microplastic on nematodes: Soil type, plastic amount and aging as determinants for the fitness of Caenorhabditis elegans. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2025, 206, 105883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phung, N.H.T.; Lien, L.T.; Ha, K.-B.N.; Tran, L.M.; Nguyen-Viet, H.-A.; Duc, P.A.; Tran, T.-V.; Nguyen, K.M.; Hoang, T.C.; Trinh, B.-S. Effects of chronic exposure to microplastics and microplastics associated with polychlorinated biphenyl 153 on Daphnia magna. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. 2023, 30, 22–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habumugisha, T.; Zhang, Z.; Uwizewe, C.; Yan, C.; Ndayishimiye, J.C.; Rehman, A.; Zhang, X. Toxicological review of micro- and nano-plastics in aquatic environments: Risks to ecosystems, food web dynamics and human health. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 278, 116426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, L.; Liu, D.-F. Emerging challenges and future directions in insect-mediated plastic degradation. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2024, 11, 394–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Li, Z.; Jia, Q.; Xu, Z. Soil microplastics pollution in agriculture. Science 2023, 379, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Hoogen, J.; Geisen, S.; Routh, D.; Ferris, H.; Traunspurger, W.; Wardle, D.A.; de Goede, R.G.M.; Adams, B.J.; Ahmad, W.; Andriuzzi, W.S.; et al. Soil nematode abundance and functional group composition at a global scale. Nature 2019, 572, 194–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Soil Properties | pH | Soil Moisture (%) | Soil Organic Carbon (g/kg) | Total Nitrogen (mg/kg) | Dissolved Organic Carbon (mg/kg) | Dissolved Organic Nitrogen (mg/kg) | Microbial Biomass Carbon (mg/kg) | Microbial Biomass Nitrogen (mg/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content | 5.13 | 13.00 | 12.8 | 654.3 | 122.8 | 38.8 | 307.2 | 17.6 |

| Measured Metrics | Microplastic | Sampling Date | Microplastic × Sampling Date | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | p | F | p | F | p | |

| Abundance | 0.97 | 0.453 | 22.52 | 0.000 | 0.30 | 0.999 |

| Richness | 0.91 | 0.499 | 24.17 | 0.000 | 0.73 | 0.796 |

| Shannon−Wiener index | 2.22 | 0.036 | 31.41 | 0.000 | 0.47 | 0.976 |

| Evenness index | 1.57 | 0.149 | 6.67 | 0.000 | 0.81 | 0.701 |

| Herbivores (%) | 2.23 | 0.036 | 34.52 | 0.000 | 0.45 | 0.982 |

| Omnivores-predators (%) | 2.33 | 0.029 | 47.73 | 0.000 | 0.40 | 0.991 |

| Bacterivores (%) | 1.24 | 0.287 | 24.62 | 0.000 | 0.71 | 0.819 |

| Fungivores (%) | 0.98 | 0.448 | 4.20 | 0.007 | 0.65 | 0.876 |

| Network Metrics | CK | 6.5 μm | 25 μm | 75 μm | 150 μm | 250 μm | 500 μm | 1000 μm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of nodes | 33 | 28 | 26 | 24 | 30 | 29 | 26 | 30 |

| Number of edges | 78 | 50 | 49 | 32 | 44 | 30 | 54 | 40 |

| Average degree | 4.73 | 3.58 | 3.77 | 2.67 | 2.93 | 2.07 | 4.15 | 2.67 |

| Network diameter | 2.81 | 3.72 | 5.04 | 2.98 | 4.60 | 4.46 | 2.98 | 3.27 |

| Average path length | 1.37 | 1.56 | 1.70 | 1.34 | 1.93 | 1.96 | 1.36 | 1.56 |

| Network density | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.17 | 0.09 |

| Modularity | 0.84 | 0.82 | 0.74 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.77 | 0.77 | 0.71 |

| Stability | 6.92 | 5.35 | 7.94 | 5.15 | 5.14 | 6.05 | 8.68 | 5.41 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

He, T.; Zhu, S.; Liu, X.; Chen, J.; He, L.; Wang, K.; Zhu, Y.; Xu, H. Size- and Time-Dependent Effects of Polyethylene Microplastics on Soil Nematode Communities: A 360-Day Field Experiment. Toxics 2026, 14, 127. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14020127

He T, Zhu S, Liu X, Chen J, He L, Wang K, Zhu Y, Xu H. Size- and Time-Dependent Effects of Polyethylene Microplastics on Soil Nematode Communities: A 360-Day Field Experiment. Toxics. 2026; 14(2):127. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14020127

Chicago/Turabian StyleHe, Tianyao, Shiyu Zhu, Xiankun Liu, Jie Chen, Liping He, Kehong Wang, Yihua Zhu, and Hongzhi Xu. 2026. "Size- and Time-Dependent Effects of Polyethylene Microplastics on Soil Nematode Communities: A 360-Day Field Experiment" Toxics 14, no. 2: 127. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14020127

APA StyleHe, T., Zhu, S., Liu, X., Chen, J., He, L., Wang, K., Zhu, Y., & Xu, H. (2026). Size- and Time-Dependent Effects of Polyethylene Microplastics on Soil Nematode Communities: A 360-Day Field Experiment. Toxics, 14(2), 127. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14020127