Persistently Elevated Gamma Power and Delayed Brain Damage in Aged Rats Acutely Exposed to Soman Without Status Epilepticus: Comparisons with Seizing Rats Treated with Midazolam or with Tezampanel and Caramiphen

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

2.2. Soman Administration and Drug Treatment

2.3. Electrode Implantation and EEG Recordings

2.4. Tissue Processing

2.5. Fluoro-Jade C Staining and Analysis

2.6. GAD-67 Immunolabeling

2.7. Estimation of Neuronal and Interneuronal Loss

2.8. Volumetric Analysis

2.9. Electrophysiological Experiments

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

| Number of Aged Male Rats Exposed to Soman | Did Not Develop SE | Died Before Anticonvulsant Treatment | Received Anticonvulsant Treatment | 24 h Survival Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 119 | 27 (23%) | 1 | 41 MDZ | 90% (37/41) |

| 50 LY293558 + CRM | 90% (45/50) |

3.1. Shorter Duration of SE in Rats Treated with LY293558 + CRM Compared with MDZ

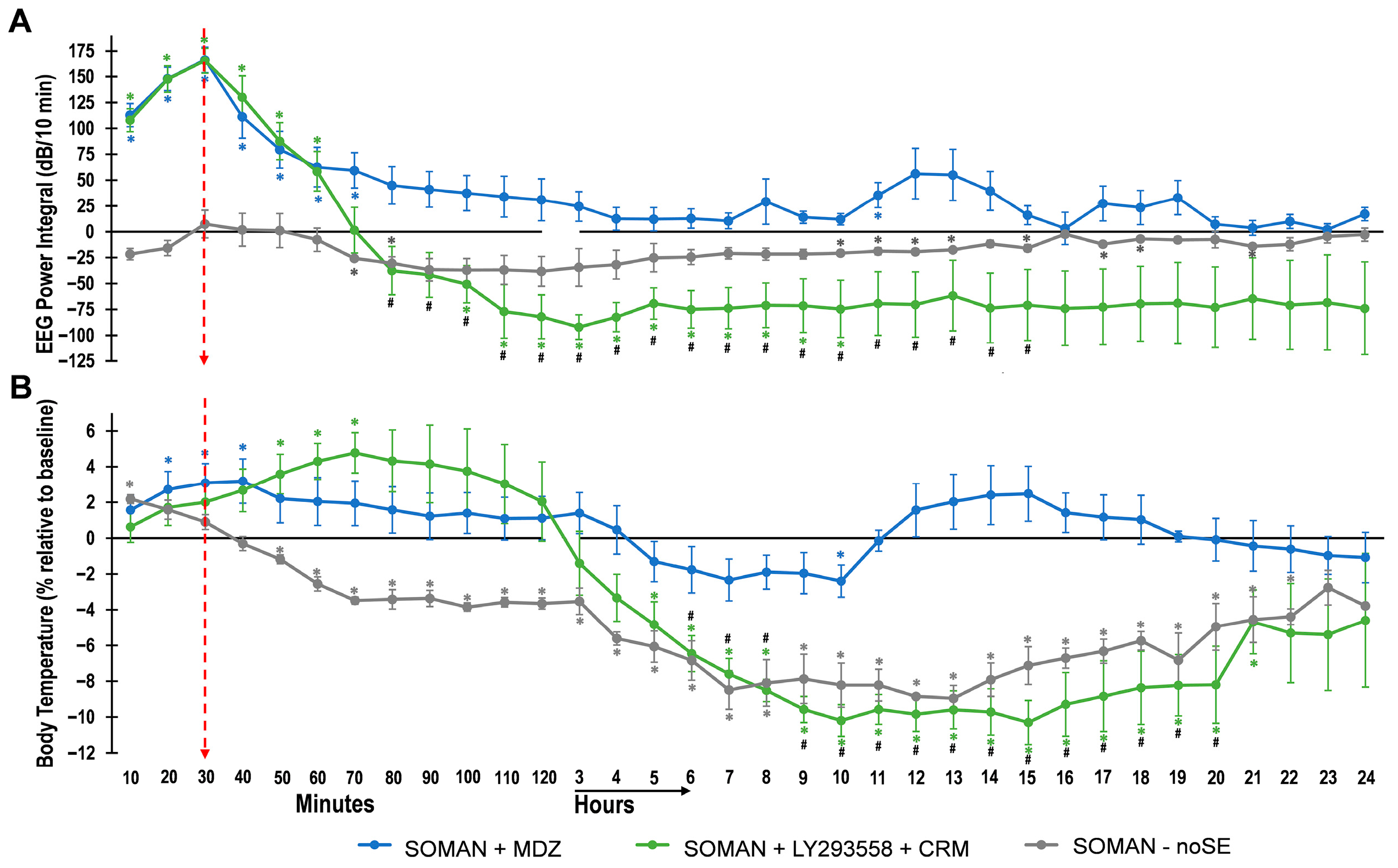

3.2. EEG Power Integral and Body Temperature over 24 h After Soman Exposure

3.3. Further Analysis of the EEG in the MDZ, LY293558 + CRM, and noSE Groups—Increased Gamma Power in the noSE Rats

3.4. Protection 293558. + CRM, but Not MDZ, Against Neuronal Degeneration—Delayed Neurodegeneration in the noSE Group

3.5. Protection by LY293558 + CRM, but Not MDZ, Against Neuronal and Interneuronal Loss—Delayed Neuronal and Interneuronal Loss in the BLA of the noSE Group

3.6. Protection by LY293558 + CRM, but Not MDZ, Against Hippocampal and Amygdalar Atrophy—Delayed Amygdalar Atrophy in the noSE Group

3.7. Protection by LY293558 + CRM, but Not MDZ, Against Reduction in Spontaneous IPSCs in the BLA—Delayed Reduction in Inhibition in the noSE Group

4. Discussion

4.1. Mechanisms of Brain Damage in the noSE Group

4.2. Severe Brain Damage After Treatment of SE with MDZ; Protection by LY293558 + CRM

4.3. Do Changes in Body Temperature Play a Role in Brain Damage?

4.4. Do Changes in the Power of Specific Frequencies Have Predictive Value for the Occurrence of SE or Neuropathology Outcomes?

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mauricio, E.A.; Freeman, W.D. Status epilepticus in the elderly: Differential diagnosis and treatment. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2011, 7, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, M.; Eshraghi, M.; Akers, K.G.; Hadidchi, S.; Kakara, M.; Nasseri, M.; Mahulikar, A.; Marawar, R. Outcomes of status epilepticus and their predictors in the elderly—A systematic review. Seizure 2020, 81, 210–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodward, M.R.; Armahizer, M.J.; Wang, T.I.; Badjatia, N.; Johnson, E.L.; Gilmore, E.J. Status epilepticus in older adults: A critical review. Epilepsia 2025, 66, 3118–3137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newmyer, L.; Verdery, A.M.; Wang, H.; Margolis, R. Population aging, demographic metabolism, and the rising tide of late middle age to older adult loneliness around the world. Popul. Dev. Rev. 2022, 48, 829–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aroniadou-Anderjaska, V.; Apland, J.P.; Figueiredo, T.H.; de Araujo Furtado, M.; Braga, M.F. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (nerve agents) as weapons of mass destruction: History, mechanisms of action, and medical countermeasures. Neuropharmacology 2020, 181, 108298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aroniadou-Anderjaska, V.; Figueiredo, T.H.; de Araujo Furtado, M.; Pidoplichko, V.I.; Braga, M.F.M. Mechanisms of organophosphate toxicity and the role of acetylcholinesterase inhibition. Toxics 2023, 11, 866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirin, G.S.; Zhang, Y. How is acetylcholinesterase phosphonylated by soman? An ab initio QM/MM molecular dynamics study. J. Phys. Chem. A 2014, 118, 9132–9139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, R.W. GABAA receptor: Positive and negative allosteric modulators. Neuropharmacology 2018, 136, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newmark, J. Therapy for acute nerve agent poisoning: An update. Neurol. Clin. Pract. 2019, 9, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorecki, L.; Pejchal, J.; Torruellas, C.; Korabecny, J.; Soukup, O. Midazolam—A diazepam replacement for the management of nerve agent-induced seizures. Neuropharmacology 2024, 261, 110171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, S.D.; Reddy, D.S. Midazolam as an anticonvulsant antidote for organophosphate intoxication—A pharmacotherapeutic appraisal. Epilepsia 2015, 56, 813–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, T.; McDonough, J.H., Jr.; Koplovitz, I. Anticonvulsants for soman-induced seizure activity. J. Biomed. Sci. 1999, 6, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.M.; Esmaeil, N.; Maren, S.; MacDonald, R.L. Characterization of pharmacoresistance to benzodiazepines in the rat Li-pilocarpine model of status epilepticus. Epilepsy Res. 2002, 50, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodkin, H.P.; Liu, X.; Holmes, G.L. Diazepam terminates brief but not prolonged seizures in young, naïve rats. Epilepsia 2003, 44, 1109–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilat, E.; Kadar, T.; Levy, A.; Rabinovitz, I.; Cohen, G.; Kapon, Y.; Sahar, R.; Brandeis, R. Anticonvulsant treatment of sarin-induced seizures with nasal midazolam: An electrographic, behavioral, and histological study in freely moving rats. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2005, 209, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Kuruba, R.; Reddy, D.S. Midazolam-resistant seizures and brain injury after acute intoxication of diisopropylfluorophosphate, an organophosphate pesticide and surrogate for nerve agents. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2018, 367, 302–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apland, J.P.; Aroniadou-Anderjaska, V.; Figueiredo, T.H.; Rossetti, F.; Miller, S.L.; Braga, M.F. The limitations of diazepam as a treatment for nerve agent-induced seizures and neuropathology in rats: Comparison with UBP302. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2014, 351, 359–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Araujo Furtado, M.; Aroniadou-Anderjaska, V.; Figueiredo, T.H.; Apland, J.P.; Braga, M.F.M. Electroencephalographic analysis in soman-exposed 21-day-old rats and the effects of midazolam or LY293558 with caramiphen. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2020, 1479, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueiredo, T.H.; Aroniadou-Anderjaska, V.; Pidoplichko, V.I.; Apland, J.P.; Braga, M.F.M. Antiseizure and neuroprotective efficacy of midazolam in comparison with tezampanel (LY293558) against soman-induced status epilepticus. Toxics 2022, 10, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumley, L.; Miller, D.; Muse, W.T.; Marrero-Rosado, B.; de Araujo Furtado, M.; Stone, M.; McGuire, J.; Whalley, C. Neurosteroid and benzodiazepine combination therapy reduces status epilepticus and long-term effects of whole-body sarin exposure in rats. Epilepsia Open 2019, 4, 382–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Supasai, S.; González, E.A.; Rowland, D.J.; Hobson, B.; Bruun, D.A.; Guignet, M.A.; Soares, S.; Singh, V.; Wulff, H.; Saito, N.; et al. Acute administration of diazepam or midazolam minimally alters long-term neuropathological effects in the rat brain following acute intoxication with diisopropylfluorophosphate. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 886, 173538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gage, M.; Rao, N.S.; Samidurai, M.; Putra, M.; Vasanthi, S.S.; Meyer, C.; Wang, C.; Thippeswamy, T. Soman (GD) rat model to mimic civilian exposure to nerve agent: Mortality, video-EEG based status epilepticus severity, sex differences, spontaneously recurring seizures, and brain pathology. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2022, 15, 798247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Araujo Furtado, M.; Aroniadou-Anderjaska, V.; Figueiredo, T.H.; Pidoplichko, V.I.; Apland, J.P.; Rossetti, K.; Braga, M.F.M. Preventing long-term brain damage by nerve agent-induced status epilepticus in rat models applicable to infants: Significant neuroprotection by tezampanel combined with caramiphen but not by midazolam treatment. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2024, 388, 432–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naylor, D.E.; Liu, H.; Niquet, J.; Wasterlain, C.G. Rapid surface accumulation of NMDA receptors increases glutamatergic excitation during status epilepticus. Neurobiol. Dis. 2013, 54, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodkin, H.P.; Joshi, S.; Mtchedlishvili, Z.; Brar, J.; Kapur, J. Subunit-specific trafficking of GABA(A) receptors during status epilepticus. J. Neurosci. 2008, 28, 2527–2538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeb, T.Z.; Nakamura, Y.; Frost, G.D.; Davies, P.A.; Moss, S.J. Disrupted Cl (−) homeostasis contributes to reductions in the inhibitory efficacy of diazepam during hyperexcited states. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2013, 38, 2453–2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aroniadou-Anderjaska, V.; Figueiredo, T.H.; de Araujo Furtado, M.; Pidoplichko, V.I.; Lumley, L.A.; Braga, M.F.M. Alterations in GABAA receptor-mediated inhibition triggered by status epilepticus and their role in epileptogenesis and increased anxiety. Neurobiol. Dis. 2024, 200, 106633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.E.; Parikh, A.O.; Ellis, C.; Myers, J.S.; Litt, B. Timing is everything: Where status epilepticus treatment fails. Ann. Neurol. 2017, 82, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullal, G.; Fahnestock, M.; Racine, R. Time-dependent effect of kainate-induced seizures on glutamate receptor GluR5, GluR6, and GluR7 mRNA and protein expression in rat hippocampus. Epilepsia 2005, 46, 616–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajasekaran, K.; Todorovic, M.; Kapur, J. Calcium-permeable AMPA receptors are expressed in a rodent model of status epilepticus. Ann. Neurol. 2012, 72, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, S.; Rajasekaran, K.; Sun, H.; Williamson, J.; Kapur, J. Enhanced AMPA receptor-mediated neurotransmission on CA1 pyramidal neurons during status epilepticus. Neurobiol. Dis. 2017, 103, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amakhin, D.V.; Soboleva, E.B.; Ergina, J.L.; Malkin, S.L.; Chizhov, A.V.; Zaitsev, A.V. Seizure-induced potentiation of AMPA receptor-mediated synaptic transmission in the entorhinal cortex. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bleakman, R.; Schoepp, D.D.; Ballyk, B.; Bufton, H.; Sharpe, E.F.; Thomas, K.; Ornstein, P.L.; Kamboj, R.K. Pharmacological discrimination of GluR5 and GluR6 kainate receptor subtypes by (3S,4aR,6R,8aR)-6-[2-(1(2)H-tetrazole-5-yl) ethyl]decahydroisoquinoline-3-carboxylic acid. Mol. Pharmacol. 1996, 49, 581–585. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8609884/ (accessed on 21 December 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apland, J.P.; Aroniadou-Anderjaska, V.; Figueiredo, T.H.; Pidoplichko, V.I.; Rossetti, K.; Braga, M.F.M. Comparing the antiseizure and neuroprotective efficacy of LY293558, diazepam, caramiphen, and LY293558-caramiphen combination against soman in a rat model relevant to the pediatric population. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2018, 365, 314–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueiredo, T.H.; Aroniadou-Anderjaska, V.; Pidoplichko, V.I.; Furtado, M.A.; Rossetti, K.; Lumley, L.A.; Braga, M.F.M. Sex-dependent differences in the antiseizure and neuroprotective effects of midazolam after soman exposure: Superior, sex-independent efficacy of tezampanel and caramiphen. Exp. Neurol. 2025, 393, 115412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raveh, L.; Chapman, S.; Cohen, G.; Alkalay, D.; Gilat, E.; Rabinovitz, I.; Weissman, B.A. The involvement of the NMDA receptor complex in the protective effect of anticholinergic drugs against soman poisoning. Neurotoxicology 1999, 20, 551–559. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10499354/ (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- Figueiredo, T.H.; Aroniadou-Anderjaska, V.; Qashu, F.; Apland, J.P.; Pidoplichko, V.; Stevens, D.; Ferrara, T.M.; Braga, M.F. Neuroprotective efficacy of caramiphen against soman and mechanisms of its action. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2011, 164, 1495–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apland, J.P.; Aroniadou-Anderjaska, V.; Figueiredo, T.H.; de Araujo Furtado, M.; Braga, M.F.M. Full protection against soman-induced seizures and brain damage by LY293558 and caramiphen combination treatment in adult rats. Neurotox. Res. 2018, 34, 511–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poza, J.J. Management of epilepsy in the elderly. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2007, 3, 723–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siniscalchi, A. Treatment of epilepsy in the elderly people. BMC Geriatr. 2010, 10, L47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.G.; Cho, Y.W.; Kim, K.T.; Kim, D.W.; Yang, K.I.; Lee, S.T.; Byun, J.I.; No, Y.J.; Kang, K.W.; Kim, D.; et al. Pharmacological treatment of epilepsy in elderly patients. J. Clin. Neurol. 2020, 16, 556–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, E.A.; Rindy, A.C.; Guignet, M.A.; Calsbeek, J.J.; Bruun, D.A.; Dhir, A.; Andrew, P.; Saito, N.; Rowland, D.J.; Harvey, D.J.; et al. The chemical convulsant diisopropylfluorophosphate (DFP) causes persistent neuropathology in adult male rats independent of seizure activity. Arch. Toxicol. 2020, 94, 2149–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apland, J.P.; Aroniadou-Anderjaska, V.; Figueiredo, T.H.; Prager, E.M.; Olsen, C.H.; Braga, M.F.M. Susceptibility to soman toxicity and efficacy of LY293558 against soman-induced seizures and neuropathology in 10-month-old male rats. Neurotox. Res. 2017, 32, 694–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racine, R.J. Modification of seizure activity by electrical stimulation. II. Motor seizure. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1972, 32, 281–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, T.H.; Qashu, F.; Apland, J.P.; Aroniadou-Anderjaska, V.; Souza, A.P.; Braga, M.F. The GluK1 (GluR5) kainate/α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptor antagonist LY293558 reduces soman-induced seizures and neuropathology. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2011, 336, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lumley, L.A.; Nguyen, D.A.; de Araujo Furtado, M.; Niquet, J.; Linz, E.O.; Schultz, C.R.; Stone, M.F.; Wasterlain, C.G. Efficacy of lacosamide and rufinamide as adjuncts to midazolam–ketamine treatment against cholinergic-induced status epilepticus in rats. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2024, 388, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Araujo Furtado, M.; Zheng, A.; Sedigh-Sarvestani, M.; Lumley, L.; Lichtenstein, S.; Yourick, D. Analyzing large data sets acquired through telemetry from rats exposed to organophosphorous compounds: An EEG study. J. Neurosci. Methods 2009, 184, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumley, L.A.; Rossetti, F.; de Araujo Furtado, M.; Marrero-Rosado, B.; Schultz, C.R.; Schultz, M.K.; Niquet, J.; Wasterlain, C.G. Dataset of EEG power integral, spontaneous recurrent seizure and behavioral responses following combination drug therapy in soman-exposed rats. Data Brief 2019, 27, 104629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apland, J.P.; Figueiredo, T.H.; Qashu, F.; Aroniadou-Anderjaska, V.; Souza, A.P.; Braga, M.F. Higher susceptibility of the ventral versus the dorsal hippocampus and the posteroventral versus anterodorsal amygdala to soman-induced neuropathology. Neurotoxicology 2010, 31, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aroniadou-Anderjaska, V.; Fritsch, B.; Qashu, F.; Braga, M.F. Pathology and pathophysiology of the amygdala in epileptogenesis and epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 2008, 78, 102–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choy, M.; Dadgar-Kiani, E.; Cron, G.O.; Duffy, B.A.; Schmid, F.; Edelman, B.J.; Asaad, M.; Chan, R.W.; Vahdat, S.; Lee, J.H. Repeated hippocampal seizures lead to brain-wide reorganization of circuits and seizure propagation pathways. Neuron 2022, 110, 221–236.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fastenrath, M.; Coynel, D.; Spalek, K.; Milnik, A.; Gschwind, L.; Roozendaal, B.; Papassotiropoulos, A.; de Quervain, D.J. Dynamic modulation of amygdala-hippocampal connectivity by emotional arousal. J. Neurosci. 2014, 34, 13935–13947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Šimić, G.; Tkalčić, M.; Vukić, V.; Mulc, D.; Španić, E.; Šagud, M.; Olucha-Bordonau, F.E.; Vukšić, M.; Hof, P.R. Understanding emotions: Origins and roles of the amygdala. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasim, S.E.; Mohan, U.R.; Stein, J.M.; Jacobs, J. Neuronal activity in the human amygdala and hippocampus enhances emotional memory encoding. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2023, 7, 754–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundersen, H.J.; Jensen, E.B.; Kiêu, K.; Nielsen, J. The efficiency of systematic sampling in stereology—Reconsidered. J. Microsc. 1999, 193, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, C.; Hof, P.R. Recommendations for straightforward and rigorous methods of counting neurons based on a computer simulation approach. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 2000, 20, 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundersen, H.J.; Bendtsen, T.F.; Korbo, L.; Marcussen, N.; Møller, A.; Nielsen, K.; Nyengaard, J.R.; Pakkenberg, B.; Sørensen, F.B.; Vesterby, A.; et al. Some new, simple and efficient stereological methods and their use in pathological research and diagnosis. APMIS 1988, 96, 379–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paxinos, G.; Watson, C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates, 4th ed.; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sah, P.; Faber, E.S.; Lopez de Armentia, M.; Power, J. The amygdaloid complex: Anatomy and physiology. Physiol. Rev. 2003, 83, 803–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pidoplichko, V.I.; Aroniadou-Anderjaska, V.; Prager, E.M.; Figueiredo, T.H.; Almeida-Suhett, C.P.; Miller, S.L.; Braga, M.F. ASIC1a activation enhances inhibition in the basolateral amygdala and reduces anxiety. J. Neurosci. 2014, 34, 3130–3141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pidoplichko, V.I.; Aroniadou-Anderjaska, V.; Figueiredo, T.H.; Wilbraham, C.; Braga, M.F.M. Increased inhibitory activity in the basolateral amygdala and decreased anxiety during estrus: A potential role for ASIC1a channels. Brain Res. 2021, 1770, 147628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aroniadou-Anderjaska, V.; Pidoplichko, V.I.; Figueiredo, T.H.; Braga, M.F.M. Oscillatory synchronous inhibition in the basolateral amygdala and its primary dependence on NR2A-containing NMDA receptors. Neuroscience 2018, 373, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffatt, A.; Mohammed, F.; Eddleston, M.; Azher, S.; Eyer, P.; Buckley, N.A. Hypothermia and fever after organophosphorus poisoning in humans—A prospective case series. J. Med. Toxicol. 2010, 6, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niquet, J.; Baldwin, R.; Gezalian, M.; Wasterlain, C.G. Deep hypothermia for the treatment of refractory status epilepticus. Epilepsy Behav. 2015, 49, 313–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollandt, S.; Bleck, T.P. Thermoregulation in epilepsy. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2018, 157, 737–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popescu, A.T.; Paré, D. Synaptic interactions underlying synchronized inhibition in the basal amygdala: Evidence for existence of two types of projection cells. J. Neurophysiol. 2011, 105, 687–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nokubo, M.; Kitani, K.; Ohta, M.; Kanai, S.; Sato, Y.; Masuda, Y. Age-dependent increase in the threshold for pentylenetetrazole-induced maximal seizure in mice. Life Sci. 1986, 38, 1999–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephen, L.J.; Brodie, M.J. Epilepsy in elderly people. Lancet 2000, 355, 1441–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Yu, W.; Lü, Y. The causes of new-onset epilepsy and seizures in the elderly. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2016, 12, 1425–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A.; Jette, N.; Husain, M.; Sander, J.W. Epilepsy in older people. Lancet 2020, 395, 735–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitani, K.; Sato, Y.; Kanai, S.; Nokubo, M.; Ohta, M.; Masuda, Y. Age related increased threshold for electroshock seizure in BDF1 mice. Life Sci. 1985, 36, 657–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kim, H.J. Normal aging induces changes in the brain and neurodegeneration progress: Review of the structural, biochemical, metabolic, cellular, and molecular changes. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 931536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujikawa, D.G. Prolonged seizures and cellular injury: Understanding the connection. Epilepsy Behav. 2005, 7, S3–S11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaínza-Lein, M.; Barcia Aguilar, C.; Piantino, J.; Chapman, K.E.; Sánchez Fernández, I.; Amengual-Gual, M.; Anderson, A.; Appavu, B.; Arya, R.; Brenton, J.N.; et al. Pediatric Status Epilepticus Research Group. Factors associated with long-term outcomes in pediatric refractory status epilepticus. Epilepsia 2021, 62, 2190–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosque Varela, P.; Machegger, L.; Steinbacher, J.; Oellerer, A.; Pfaff, J.; McCoy, M.; Trinka, E.; Kuchukhidze, G. Brain damage caused by status epilepticus: A prospective MRI study. Epilepsy Behav. 2024, 161, 110081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naughton, S.X.; Terry, A.V., Jr. Neurotoxicity in acute and repeated organophosphate exposure. Toxicology 2018, 408, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, Y.H.; Lein, P.J. Mechanisms of organophosphate neurotoxicity. Curr. Opin. Toxicol. 2021, 26, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prager, E.M.; Aroniadou-Anderjaska, V.; Almeida-Suhett, C.P.; Figueiredo, T.H.; Apland, J.P.; Braga, M.F. Acetylcholinesterase inhibition in the basolateral amygdala plays a key role in the induction of status epilepticus after soman exposure. Neurotoxicology 2013, 38, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, K.F.; Santos, E.; Blair, R.E.; Deshpande, L.S. Targeting intracellular calcium stores alleviates neurological morbidities in a DFP-based rat model of Gulf War illness. Toxicol. Sci. 2019, 169, 567–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banks, C.N.; Lein, P.J. A review of experimental evidence linking neurotoxic organophosphorus compounds and inflammation. Neurotoxicology 2012, 33, 575–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, A.V., Jr. Functional consequences of repeated organophosphate exposure: Potential non-cholinergic mechanisms. Pharmacol. Ther. 2012, 134, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorke, D.E.; Oz, M. A review on oxidative stress in organophosphate-induced neurotoxicity. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2025, 180, 106735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mense, S.M.; Sengupta, A.; Lan, C.; Zhou, M.; Bentsman, G.; Volsky, D.J.; Whyatt, R.M.; Perera, F.P.; Zhang, L. The common insecticides cyfluthrin and chlorpyrifos alter the expression of a subset of genes with diverse functions in primary human astrocytes. Toxicol. Sci. 2006, 93, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prager, E.M.; Pidoplichko, V.I.; Aroniadou-Anderjaska, V.; Apland, J.P.; Braga, M.F. Pathophysiological mechanisms underlying increased anxiety after soman exposure: Reduced GABAergic inhibition in the basolateral amygdala. Neurotoxicology 2014, 44, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timofeeva, O.A.; Gordon, C.J. Changes in EEG power spectra and behavioral states in rats exposed to the acetylcholinesterase inhibitor chlorpyrifos and muscarinic agonist oxotremorine. Brain Res. 2001, 893, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, D.A.; Niquet, J.; Marrero-Rosado, B.; Schultz, C.R.; Stone, M.F.; de Araujo Furtado, M.; Biney, A.K.; Lumley, L.A. Age differences in organophosphorus nerve agent-induced seizure, blood–brain barrier integrity, and neurodegeneration in midazolam-treated rats. Exp. Neurol. 2025, 385, 115122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steier, H.G.; Schultz, C.R.; Niquet, J.; Nguyen, D.A.; Stone, M.F.; Biney, A.K.; de Araujo Furtado, M.; Wasterlain, C.G.; Lumley, L.A. Perampanel as a second-line therapy to midazolam reduces soman-induced status epilepticus and neurodegeneration in rats. Epilepsia Open 2025, 10, 1187–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unal, C.B.; Demiral, Y.; Ulus, I.H. The effects of choline on body temperature in conscious rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1998, 363, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, C.J.; Grantham, T.A. Effect of central and peripheral cholinergic antagonists on chlorpyrifos-induced changes in body temperature in the rat. Toxicology 1999, 142, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, A.; Ishimaru, H.; Ikarashi, Y.; Kishi, E.; Maruyama, Y. Hypothalamic cholinergic regulation of body temperature and water intake in rats. Auton. Neurosci. 2001, 94, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, P.P.; Li, L.Y.; Zhang, H.M.; Li, T. Hypothermia reduces brain edema, spontaneous recurrent seizure attack, and learning memory deficits in the kainic acid treated rats. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2011, 17, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.T.; Chen, C.F.; Pang, I.H. Effect of ketamine on thermoregulation in rats. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1978, 56, 963–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, S.M.; Lipton, J.M. Effects of diazepam on body temperature of the aged squirrel monkey. Brain Res. Bull. 1981, 7, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowden, J.; Reid, C.; Dooley, P.; Corbett, D. Diazepam-induced neuroprotection: Dissociating the effects of hypothermia following global ischemia. Brain Res. 1999, 829, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzsáki, G.; Wang, X.J. Mechanisms of gamma oscillations. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2012, 35, 203–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ichim, A.M.; Barzan, H.; Moca, V.V.; Nagy-Dabacan, A.; Ciuparu, A.; Hapca, A.; Vervaeke, K.; Muresan, R.C. The gamma rhythm as a guardian of brain health. eLife 2024, 13, e100238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Van Quyen, M.; Adam, C.; Lachaux, J.P.; Martinerie, J.; Baulac, M.; Renault, B.; Varela, F.J. Temporal patterns in human epileptic activity are modulated by perceptual discriminations. NeuroReport 1997, 8, 1703–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testylier, G.; Tonduli, L.; Lallement, G. Implication of gamma band in soman-induced seizures. Acta Biotheor. 1999, 47, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verret, L.; Mann, E.O.; Hang, G.B.; Barth, A.M.; Cobos, I.; Ho, K.; Devidze, N.; Masliah, E.; Kreitzer, A.C.; Mody, I.; et al. Inhibitory interneuron deficit links altered network activity and cognitive dysfunction in Alzheimer model. Cell 2012, 149, 708–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Losa, M.; Tracy, T.E.; Ma, K.; Verret, L.; Clemente-Perez, A.; Khan, A.S.; Cobos, I.; Ho, K.; Gan, L.; Mucke, L.; et al. Nav1.1-overexpressing interneuron transplants restore brain rhythms and cognition in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron 2018, 98, 75–89.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumoto, J.Y.; Stead, M.; Kucewicz, M.T.; Matsumoto, A.J.; Peters, P.A.; Brinkmann, B.H.; Danstrom, J.C.; Goerss, S.J.; Marsh, W.R.; Meyer, F.B.; et al. Network oscillations modulate interictal epileptiform spike rate during human memory. Brain 2013, 136, 2444–2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, A.; Wang, S.; Huang, A.; Qiu, C.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, Q.; Deng, B. The role of gamma oscillations in central nervous system diseases: Mechanism and treatment. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 962957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atallah, B.V.; Scanziani, M. Instantaneous modulation of gamma oscillation frequency by balancing excitation with inhibition. Neuron 2009, 62, 566–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonough, J.H., Jr.; Clark, T.R.; Slone, T.W., Jr.; Zoeffel, D.; Brown, K.; Kim, S.; Smith, C.D. Neural lesions in the rat and their relationship to EEG delta activity following seizures induced by the nerve agent soman. Neurotoxicology 1998, 19, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Carpentier, P.; Foquin, A.; Dorandeu, F.; Lallement, G. Delta activity as an early indicator for soman-induced brain damage: A review. Neurotoxicology 2001, 22, 299–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Groups | Latency to Cessation of Initial SE | Duration of Initial SE | Total Duration of SE (in 24 h) |

|---|---|---|---|

| MDZ | 202.8 ± 66 | 223.3 ± 58 | 553.8 ± 99 |

| LY293558 + CRM | 52.6 ± 12 p = 0.07 | 90.4 ± 13 p = 0.074 | 91.2 ± 13 ** p = 0.005 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Figueiredo, T.H.; Aroniadou-Anderjaska, V.; De Araujo Furtado, M.; Pidoplichko, V.I.; Rossetti, K.; Lumley, L.A.; Braga, M.F.M. Persistently Elevated Gamma Power and Delayed Brain Damage in Aged Rats Acutely Exposed to Soman Without Status Epilepticus: Comparisons with Seizing Rats Treated with Midazolam or with Tezampanel and Caramiphen. Toxics 2026, 14, 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010022

Figueiredo TH, Aroniadou-Anderjaska V, De Araujo Furtado M, Pidoplichko VI, Rossetti K, Lumley LA, Braga MFM. Persistently Elevated Gamma Power and Delayed Brain Damage in Aged Rats Acutely Exposed to Soman Without Status Epilepticus: Comparisons with Seizing Rats Treated with Midazolam or with Tezampanel and Caramiphen. Toxics. 2026; 14(1):22. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010022

Chicago/Turabian StyleFigueiredo, Taiza H., Vassiliki Aroniadou-Anderjaska, Marcio De Araujo Furtado, Volodymyr I. Pidoplichko, Katia Rossetti, Lucille A. Lumley, and Maria F. M. Braga. 2026. "Persistently Elevated Gamma Power and Delayed Brain Damage in Aged Rats Acutely Exposed to Soman Without Status Epilepticus: Comparisons with Seizing Rats Treated with Midazolam or with Tezampanel and Caramiphen" Toxics 14, no. 1: 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010022

APA StyleFigueiredo, T. H., Aroniadou-Anderjaska, V., De Araujo Furtado, M., Pidoplichko, V. I., Rossetti, K., Lumley, L. A., & Braga, M. F. M. (2026). Persistently Elevated Gamma Power and Delayed Brain Damage in Aged Rats Acutely Exposed to Soman Without Status Epilepticus: Comparisons with Seizing Rats Treated with Midazolam or with Tezampanel and Caramiphen. Toxics, 14(1), 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010022