Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms Among Patients with Asbestos-Related Diseases in Korea

Highlights

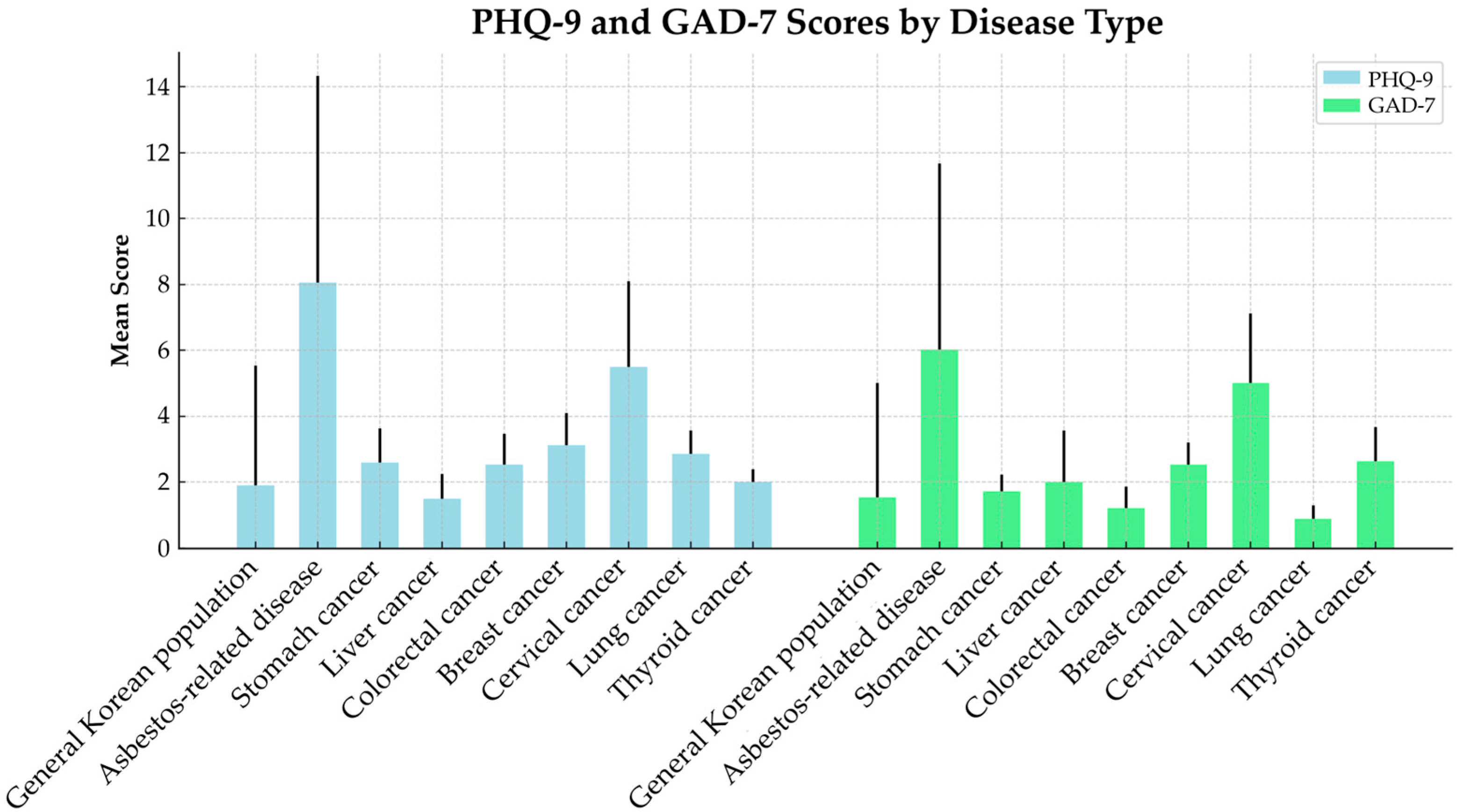

- Depression and anxiety levels measured using PHQ-9, GAD-7, and HADS among Korean patients with asbestos-related diseases (ARDs) were higher than those reported for major cancer patients in Korea, based on nationally representative KNHANES data.

- Patients with asbestosis had significantly higher depression and anxiety scores than those with malignant mesothelioma or asbestos-related lung cancer, with symptom severity increasing in line with disease grade.

- The markedly higher psychological distress observed in ARD patients compared to other cancer patients suggests that they may be subject to additional psychosocial stressors.

- These findings highlight the need to incorporate comprehensive psychosocial support into treatment strategies for patients with asbestos-related diseases.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source and Study Population

2.2. Assessment of Depression and Anxiety

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.4. Comparison with Other Cancers

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PHQ-9 | Patient Health Questionnaire-9 |

| GAD-7 | Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 |

| HADS | Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale |

| KNHANES | Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey |

References

- Huh, D.-A.; Chae, W.-R.; Choi, Y.-H.; Kang, M.-S.; Lee, Y.-J.; Moon, K.-W. Disease latency according to asbestos exposure characteristics among malignant mesothelioma and asbestos-related lung cancer cases in South Korea. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mossman, B.T.; Churg, A. Mechanisms in the pathogenesis of asbestosis and silicosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1998, 157, 1666–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamp, D.W. Asbestos-induced lung diseases: An update. Transl. Res. 2009, 153, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaurand, M.-C. Mechanisms of fiber-induced genotoxicity. Environ. Health Perspect. 1997, 105 (Suppl. S5), 1073–1084. [Google Scholar]

- Carbone, M.; Kratzke, R.A.; Testa, J.R. The Pathogenesis of Mesothelioma; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2002; pp. 2–17. [Google Scholar]

- Van Meerbeeck, J.P.; Scherpereel, A.; Surmont, V.F.; Baas, P. Malignant pleural mesothelioma: The standard of care and challenges for future management. Crit. Rev. Oncol./Hematol. 2011, 78, 92–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amin, W.; Linkov, F.; Landsittel, D.P.; Silverstein, J.C.; Bshara, W.; Gaudioso, C.; Feldman, M.D.; Pass, H.I.; Melamed, J.; Friedberg, J.S. Factors influencing malignant mesothelioma survival: A retrospective review of the National Mesothelioma Virtual Bank cohort. F1000Research 2019, 7, 1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huh, D.-A.; Choi, Y.-H.; Kim, L.; Park, K.; Lee, J.; Hwang, S.H.; Moon, K.W.; Kang, M.-S.; Lee, Y.-J. Air pollution and survival in patients with malignant mesothelioma and asbestos-related lung cancer: A follow-up study of 1591 patients in South Korea. Environ. Health 2024, 23, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumann, S.O.; Kocher, G.; Minervini, F. Epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment of the malignant pleural mesothelioma, a narrative review of literature. J. Thorac. Dis. 2021, 13, 2510–2523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, G.W.; Alberg, A.J.; Cummings, K.M.; Dresler, C. Smoking cessation after a cancer diagnosis is associated with improved survival. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2020, 15, 705–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasetti, M.; Monaco, F.; Strogovets, O.; Volpini, L.; Valentino, M.; Amati, M.; Neuzil, J.; Santarelli, L. ATG5 as biomarker for early detection of malignant mesothelioma. BMC Res. Notes 2023, 16, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, E.; Shin, D.W.; Cho, S.-I.; Park, S.; Won, Y.-J.; Yun, Y.H. Suicide rates and risk factors among Korean cancer patients, 1993–2005. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2010, 19, 2097–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.; Ma, J.; Jemal, A.; Zhao, J.; Nogueira, L.; Ji, X.; Yabroff, K.R.; Han, X. Suicide risk among individuals diagnosed with cancer in the US, 2000–2016. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2251863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, F.; Fall, K.; Mittleman, M.A.; Sparén, P.; Ye, W.; Adami, H.-O.; Valdimarsdóttir, U. Suicide and cardiovascular death after a cancer diagnosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 1310–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novello, S.; Pinto, C.; Torri, V.; Porcu, L.; Di Maio, M.; Tiseo, M.; Ceresoli, G.; Magnani, C.; Silvestri, S.; Veltri, A. The third Italian consensus conference for malignant pleural mesothelioma: State of the art and recommendations. Crit. Rev. Oncol. /Hematol. 2016, 104, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonafede, M.; Ghelli, M.; Corfiati, M.; Rosa, V.; Guglielmucci, F.; Granieri, A.; Branchi, C.; Iavicoli, S.; Marinaccio, A. The psychological distress and care needs of mesothelioma patients and asbestos-exposed subjects: A systematic review of published studies. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2018, 61, 400–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barak, Y.; Achiron, A.; Rotstfin, Z.; Elizur, A.; Noy, S. Stress associated with asbestosis: The trauma of waiting for death. Psycho-Oncology 1998, 7, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breen, L.J.; Huseini, T.; Same, A.; Peddle-McIntyre, C.J.; Lee, Y.G. Living with mesothelioma: A systematic review of patient and caregiver psychosocial support needs. Patient Educ. Couns. 2022, 105, 1904–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejegi-Memeh, S.; Sherborne, V.; Harrison, M.; Taylor, B.; Senek, M.; Tod, A.; Gardiner, C. Patients’ and informal Carers’ experience of living with Mesothelioma: A systematic rapid review and synthesis of the literature. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2022, 58, 102122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girgis, S.; Smith, A.B.; Lambert, S.; Waller, A.; Girgis, A. “It sort of hit me like a baseball bat between the eyes”: A qualitative study of the psychosocial experiences of mesothelioma patients and carers. Support. Care Cancer 2019, 27, 631–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ball, H.; Moore, S.; Leary, A. A systematic literature review comparing the psychological care needs of patients with mesothelioma and advanced lung cancer. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2016, 25, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mounchetrou Njoya, I.; Paris, C.; Dinet, J.; Luc, A.; Lighezzolo-Alnot, J.; Pairon, J.-C.; Thaon, I. Anxious and depressive symptoms in the French Asbestos-Related Diseases Cohort: Risk factors and self-perception of risk. Eur. J. Public Health 2017, 27, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinert, C.; Hill, W.G.; Winters, C.A.; Kuntz, S.W.; Rowse, K.; Hernandez, T.; Black, B.; Cudney, S. Psychosocial health status of persons seeking treatment for exposure to libby amphibole asbestos. Int. Sch. Res. Not. 2011, 2011, 735936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granieri, A. Extreme Trauma in a Polluted Area: Bonds and Relational Transformations in an Italian Community; International Forum of Psychoanalysis, 2016; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2016; pp. 94–103. [Google Scholar]

- Maurel, M.; Stoufflet, A.; Thorel, L.; Berna, V.; Gislard, A.; Letourneux, M.; Pairon, J.C.; Paris, C. Factors associated with cancer distress in the Asbestos Post-Exposure Survey (APEXS). Am. J. Ind. Med. 2009, 52, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.H.; Jiang, C.Q.; Lam, T.H.; Xu, L.; Jin, Y.L.; Cheng, K.K. Past occupational dust exposure, depressive symptoms and anxiety in retired Chinese factory workers: The Guangzhou Biobank Cohort Study. J. Occup. Health 2014, 56, 444–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clayson, H.; Seymour, J.; Noble, B. Mesothelioma from the patient’s perspective. Hematol./Oncol. Clin. 2005, 19, 1175–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arber, A.; Spencer, L. ‘It’s all bad news’: The first 3 months following a diagnosis of malignant pleural mesothelioma. Psycho-Oncology 2013, 22, 1528–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, D.-M.; Kim, J.-E.; Lee, Y.-J.; Lee, H.-H.; Lee, C.-Y.; Moon, S.-J.; Kang, M.-S. Environmental health centers for asbestos and their health impact surveys and activities. Ann. Occup. Environ. Med. 2016, 28, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.; Löwe, B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepine, J.; Godchau, M.; Brun, P. Anxiety and depression in inpatients. Lancet 1985, 326, 1425–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zigmond, A.S.; Snaith, R.P. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1983, 67, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snaith, R.P. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2003, 1, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjelland, I.; Dahl, A.A.; Haug, T.T.; Neckelmann, D. The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale: An updated literature review. J. Psychosom. Res. 2002, 52, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherborne, V.; Wood, E.; Mayland, C.R.; Gardiner, C.; Lusted, C.; Bibby, A.; Tod, A.; Taylor, B.; Ejegi-Memeh, S. The mental health and well-being implications of a Mesothelioma diagnosis: A mixed methods study. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2024, 70, 102545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Götze, H.; Friedrich, M.; Taubenheim, S.; Dietz, A.; Lordick, F.; Mehnert, A. Depression and anxiety in long-term survivors 5 and 10 years after cancer diagnosis. Support. Care Cancer 2020, 28, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinz, A.; Mehnert, A.; Kocalevent, R.-D.; Brähler, E.; Forkmann, T.; Singer, S.; Schulte, T. Assessment of depression severity with the PHQ-9 in cancer patients and in the general population. BMC Psychiatry 2016, 16, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartung, T.J.; Brähler, E.; Faller, H.; Härter, M.; Hinz, A.; Johansen, C.; Keller, M.; Koch, U.; Schulz, H.; Weis, J. The risk of being depressed is significantly higher in cancer patients than in the general population: Prevalence and severity of depressive symptoms across major cancer types. Eur. J. Cancer 2017, 72, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, L.; Huh, D.-A.; Kang, M.-S.; Park, K.; Lee, J.; Hwang, S.H.; Choi, H.J.; Lim, W.; Moon, K.W.; Lee, Y.-J. Chemical exposure from the Hebei spirit oil spill accident and its long-term effects on mental health. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 284, 116938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.-H.; Huh, D.-A.; Kim, L.; Lee, S.J.; Moon, K.W. Health risks of pest control and disinfection workers after the COVID-19 outbreak in South Korea. J. Environ. Sci. 2024, 139, 350–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.-H.; Choi, Y.-H.; Huh, D.-A.; Kim, L.; Park, K.; Lee, J.; Choi, H.J.; Lim, W.; Moon, K.W. Per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances exposures are associated with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, particularly fibrosis. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 372, 126085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.; Huh, D.-A.; Kim, L.; Choi, Y.-H.; Lee, J.; Hwang, S.H.; Choi, H.J.; Lim, W.; Moon, K.W. Levels of serum per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances and association with dyslipidemia in the Korean population. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 302, 118633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’neil, A.; Quirk, S.E.; Housden, S.; Brennan, S.L.; Williams, L.J.; Pasco, J.A.; Berk, M.; Jacka, F.N. Relationship between diet and mental health in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, e31–e42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, L.; Choi, Y.-H.; Huh, D.-A.; Moon, K.W. Associations of minimally processed and ultra-processed food intakes with cardiovascular health in Korean adults: The Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES VI), 2013–2015. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2024, 34, 1045–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, L.; Huh, D.-A.; Park, K.; Lee, J.; Hwang, S.-H.; Choi, H.J.; Lim, W.; Moon, K.W. Dietary exposure to environmental phenols and phthalates in Korean adults: Data analysis of the Korean National Environmental Health Survey (KoNEHS) 2018–2020. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2025, 267, 114597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, C.S. Disaster mental health epidemiology: Methodological review and interpretation of research findings. Psychiatry 2016, 79, 130–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.-H.; Kim, L.; Huh, D.-A.; Moon, K.W.; Kang, M.-S.; Lee, Y.-J. Association between oil spill clean-up work and thyroid cancer: Nine years of follow-up after the Hebei Spirit oil spill accident. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 199, 116041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, S.H.; Lee, Y.-J.; Choi, Y.-H.; Huh, D.-A.; Kang, M.-S.; Moon, K.W. Long-term effects of the Hebei Spirit oil spill on the prevalence and incidence of allergic disorders. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 912, 168801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Huh, D.-A.; Kim, L.; Park, K.; Choi, Y.-H.; Hwang, S.-H.; Lim, W.; Choi, H.J.; Moon, K.W.; Kang, M.-S. The short-term and long-term effects of oil spill exposure on dyslipidemia: A prospective cohort study of Health Effects Research on the Hebei Spirit Oil Spill. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2025, 219, 118321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente, M.; Reig-Botella, A.; Prados, J.C. Alterations in psychosocial health of people affected by asbestos poisoning. Rev. Saude Publica 2015, 49, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yohannes, A.M.; Alexopoulos, G.S. Depression and anxiety in patients with COPD. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2014, 23, 345–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratek, A.; Zawada, K.; Beil-Gawełczyk, J.; Beil, S.; Sozańska, E.; Krysta, K.; Barczyk, A.; Krupka-Matuszczyk, I.; Pierzchała, W. Depressiveness, symptoms of anxiety and cognitive dysfunctions in patients with asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): Possible associations with inflammation markers: A pilot study. J. Neural Transm. 2015, 122 (Suppl. S1), 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, S.; Teehan, C.; Cornwall, A.; Ball, K.; Thomas, J. ‘Hands of Time’: The experience of establishing a support group for people affected by mesothelioma. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2008, 17, 585–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Malignant Mesothelioma | Lung Cancer | Asbestosis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 1: Severe | Grade 2: Moderate | Grade 3: Mild | |||

| Total | 4 (100.0) | 21 (100.0) | 16 (100.0) | 95 (100.0) | 139 (100.0) |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 2 (50.0) | 16 (76.2) | 13 (81.3) | 65 (68.4) | 67 (48.2) |

| Female | 2 (50.0) | 5 (23.8) | 3 (18.8) | 30 (31.6) | 72 (51.8) |

| Age | |||||

| 50–59 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (3.2) | 1 (0.7) |

| 60–69 | 3 (75.0) | 6 (28.6) | 0 (0.0) | 11 (11.6) | 22 (15.8) |

| 70–79 | 1 (25.0) | 10 (47.6) | 9 (56.3) | 36 (37.9) | 56 (40.3) |

| 80–89 | 0 (0.0) | 5 (23.8) | 7 (43.8) | 39 (41.1) | 53 (38.1) |

| ≥90 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (6.3) | 7 (5.0) |

| Smoking status | |||||

| Never | 0 (0.0) | 3 (14.3) | 1 (6.3) | 18 (18.9) | 62 (44.6) |

| Past smoker | 0 (0.0) | 12 (57.1) | 7 (43.8) | 19 (20.0) | 23 (16.5) |

| Current smoker | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (3.2) | 5 (3.6) |

| Unknown | 4 (100.0) | 6 (28.6) | 8 (50.0) | 55 (57.9) | 49 (35.3) |

| Region | |||||

| Seoul | 4 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.1) | 1 (0.7) |

| Incheon | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (4.3) |

| Gyeonggi-do | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.8) | 3 (18.8) | 5 (5.3) | 8 (5.8) |

| Gyeonsangnam-do | 0 (0.0) | 4 (19.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (4.2) | 1 (0.7) |

| Busan | 0 (0.0) | 5 (23.8) | 2 (12.5) | 25 (26.3) | 21 (15.1) |

| Chungcheongnam-do | 0 (0.0) | 10 (47.6) | 11 (68.8) | 60 (63.2) | 102 (73.4) |

| Variables | n (%) | PHQ-9 | GAD-7 | HADS-A | HADS-D | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | p | Mean ± SD | p | Mean ± SD | p | Mean ± SD | p | ||

| Total | 275 (100.0) | 8.06 ± 6.27 | 6.02 ± 5.64 | 7.09 ± 5.44 | 8.41 ± 5.07 | ||||

| Sex | |||||||||

| Male | 163 (59.3) | 8.23 ± 6.25 | 0.599 | 6.02 ± 5.56 | 0.997 | 7.28 ± 5.49 | 0.496 | 8.73 ± 4.99 | 0.209 |

| Female | 112 (40.7) | 7.82 ± 6.32 | 6.02 ± 5.79 | 6.82 ± 5.39 | 7.95 ± 5.18 | ||||

| Age | |||||||||

| 50–59 | 4 (1.5) | 4.50 ± 2.08 | 0.623 | 3.25 ± 3.95 | 0.647 | 3.75 ± 4.50 | 0.122 | 4.00 ± 2.94 | 0.007 |

| 60–69 | 45 (15.3) | 7.21 ± 6.00 | 5.33 ± 5.66 | 5.57 ± 5.20 | 6.55 ± 4.92 | ||||

| 70–79 | 112 (40.7) | 8.07 ± 6.32 | 5.96 ± 5.37 | 7.21 ± 5.14 | 8.64 ± 4.63 | ||||

| 80–89 | 104 (37.8) | 8.53 ± 6.61 | 6.33 ± 6.05 | 7.43 ± 5.82 | 8.71 ± 5.42 | ||||

| ≥90 | 13 (4.7) | 8.08 ± 4.44 | 7.23 ± 5.15 | 9.23 ± 5.04 | 11.38 ± 4.72 | ||||

| Smoking status | |||||||||

| Never | 185 (67.3) | 6.73 ± 6.15 | 0.005 | 4.67 ± 5.61 | 0.008 | 5.63 ± 5.38 | 0.001 | 7.37 ± 5.53 | 0.034 |

| Past smoker | 61 (22.2) | 7.00 ± 5.38 | 5.44 ± 5.16 | 6.44 ± 5.77 | 7.87 ± 4.77 | ||||

| Current smoker | 8 (2.9) | 7.38 ± 5.83 | 5.38 ± 4.50 | 5.63 ± 3.16 | 9.00 ± 3.38 | ||||

| Unknown | 21 (7.6) | 9.56 ± 6.53 | 7.30 ± 5.75 | 8.52 ± 5.12 | 9.36 ± 4.85 | ||||

| Region | |||||||||

| Seoul | 6 (2.2) | 7.50 ± 6.89 | 0.225 | 4.50 ± 5.96 | 0.113 | 6.67 ± 3.83 | 0.009 | 6.17 ± 4.62 | 0.222 |

| Incheon | 7 (2.5) | 7.71 ± 4.11 | 5.57 ± 5.03 | 8.57 ± 5.06 | 6.57 ± 3.74 | ||||

| Gyeonggi-do | 17 (6.2) | 8.24 ± 4.63 | 5.00 ± 4.02 | 6.65 ± 3.95 | 7.82 ± 3.63 | ||||

| Gyeonsangnam-do | 9 (3.3) | 3.33 ± 4.50 | 2.89 ± 4.73 | 3.22 ± 6.02 | 5.56 ± 5.90 | ||||

| Busan | 53 (19.3) | 9.19 ± 5.98 | 7.74 ± 5.51 | 9.28 ± 5.42 | 9.34 ± 4.46 | ||||

| Chungcheongnam-do | 183 (66.5) | 7.98 ± 6.54 | 5.85 ± 5.79 | 6.64 ± 5.43 | 8.48 ± 5.32 | ||||

| Diagnosis | |||||||||

| Malignant mesothelioma | 4 (1.5) | 6.50 ± 7.42 | 0.005 | 3.75 ± 7.50 | 0.024 | 6.50 ± 4.66 | 0.017 | 5.50 ± 5.80 | 0.007 |

| Lung cancer | 21 (7.6) | 6.62 ± 6.00 | 4.71 ± 5.82 | 6.33 ± 7.10 | 6.38 ± 4.09 | ||||

| Asbestosis (Grade 1: Severe) | 16 (5.8) | 11.75 ± 4.92 | 8.88 ± 5.18 | 9.88 ± 4.88 | 10.75 ± 3.28 | ||||

| Asbestosis (Grade 2: Moderate) | 95 (34.5) | 9.36 ± 6.43 | 7.01 ± 5.62 | 8.13 ± 5.29 | 9.44 ± 4.94 | ||||

| Asbestosis (Grade 3: Mild) | 139 (50.6) | 7.01 ± 6.05 | 5.29 ± 5.49 | 6.19 ± 5.18 | 7.83 ± 5.25 | ||||

| Variables | PHQ-9 Subscale Score [n (%)] | GAD-7 Subscale Score [n (%)] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild (5–9) | Moderate (10–14) | Severe (≥15) | p | Mild (5–9) | Moderate (10–14) | Severe (≥15) | p | |

| Total (n = 275) | 67 (24.4) | 63 (22.9) | 44 (16.0) | 83 (30.2) | 41 (14.9) | 29 (10.5) | ||

| Diagnosis | ||||||||

| Malignant mesothelioma (n = 4) | 1 (25.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (25.0) | 0.057 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (25.0) | 0.008 |

| Lung cancer (n = 21) | 4 (19.0) | 4 (19.0) | 3 (14.3) | 5 (23.8) | 1 (4.8) | 2 (9.5) | ||

| Asbestosis (Grade 1: Severe) (n = 16) | 3 (18.8) | 9 (56.3) | 3 (18.8) | 5 (31.3) | 7 (43.8) | 1 (6.3) | ||

| Asbestosis (Grade 2: Moderate) (n = 95) | 24 (25.3) | 24 (25.3) | 19 (20.0) | 32 (33.7) | 20 (21.1) | 10 (10.5) | ||

| Asbestosis (Grade 3: Mild) (n = 139) | 35 (25.2) | 26 (18.7) | 18 (12.9) | 41 (29.5) | 13 (9.4) | 15 (10.8) | ||

| Variables | HADS-A Subscale Score [n (%)] | HADS-D Subscale Score [n (%)] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suggestive (8–10) | Probable (≥11) | p | Suggestive (8–10) | Probable (≥11) | p | |

| Total (n = 275) | 48 (17.5) | 71 (25.8) | 61 (22.2) | 90 (32.7) | ||

| Diagnosis | ||||||

| Malignant mesothelioma (n = 4) | 1 (25.0) | 1 (25.0) | 0.256 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (25.0) | 0.010 |

| Lung cancer (n = 21) | 1 (4.8) | 5 (23.8) | 3 (14.3) | 4 (19.0) | ||

| Asbestosis (Grade 1: Severe) (n = 16) | 2 (12.5) | 7 (43.8) | 3 (18.8) | 10 (62.5) | ||

| Asbestosis (Grade 2: Moderate) (n = 95) | 21 (22.1) | 28 (29.5) | 29 (30.5) | 33 (34.7) | ||

| Asbestosis (Grade 3: Mild) (n = 139) | 23 (16.5) | 30 (21.6) | 26 (18.7) | 42 (30.2) | ||

| Variables | PHQ-9 | GAD-7 | HADS-A | HADS-D | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (95% CI) | p | β (95% CI) | p | β (95% CI) | p | β (95% CI) | p | |

| Diagnosis | ||||||||

| Malignant mesothelioma | 4.47 (−4.99, 13.92) | 0.029 | 3.35 (−5.20, 11.99) | 0.111 | 6.43 (−1.68, 14.53) | 0.042 | 6.35 (−1.28, 13.98) | 0.030 |

| Lung cancer | 7.09 (3.71, 10.47) | 4.69 (1.63, 7.75) | 6.69 (3.79, 9.59) | 6.55 (3.83, 9.28) | ||||

| Asbestosis (Grade 1: Severe) | 10.87 (7.07, 14.67) | 8.31 (4.87, 11.75) | 9.47 (6.21, 12.73) | 10.01 (6.94, 13.08) | ||||

| Asbestosis (Grade 2: Moderate) | 8.34 (5.89, 10.79) | 6.13 (3.91, 8.35) | 7.43 (5.33, 9.53) | 8.53 (6.55, 10.51) | ||||

| Asbestosis (Grade 3: Mild) | 6.29 (3.99, 8.60) | 4.78 (2.70, 6.87) | 5.87 (3.90, 7.85) | 7.37 (5.51, 9.23) | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kang, M.-S.; Lee, M.-R.; Hwangbo, Y. Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms Among Patients with Asbestos-Related Diseases in Korea. Toxics 2025, 13, 703. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13080703

Kang M-S, Lee M-R, Hwangbo Y. Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms Among Patients with Asbestos-Related Diseases in Korea. Toxics. 2025; 13(8):703. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13080703

Chicago/Turabian StyleKang, Min-Sung, Mee-Ri Lee, and Young Hwangbo. 2025. "Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms Among Patients with Asbestos-Related Diseases in Korea" Toxics 13, no. 8: 703. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13080703

APA StyleKang, M.-S., Lee, M.-R., & Hwangbo, Y. (2025). Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms Among Patients with Asbestos-Related Diseases in Korea. Toxics, 13(8), 703. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13080703