Comprehensive Cross-Sectional Study of the Triglyceride Glucose Index, Organophosphate Pesticide Exposure, and Cardiovascular Diseases: A Machine Learning Integrated Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participant Group

2.2. Evaluation of the TyG Index

2.3. Condition of the Exposure

2.4. Covariates

2.5. Data Analysis

2.6. Machine Learning Analysis

2.7. SHAP Interpretable Analysis

2.8. Network Toxicology Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Description of Study Participants

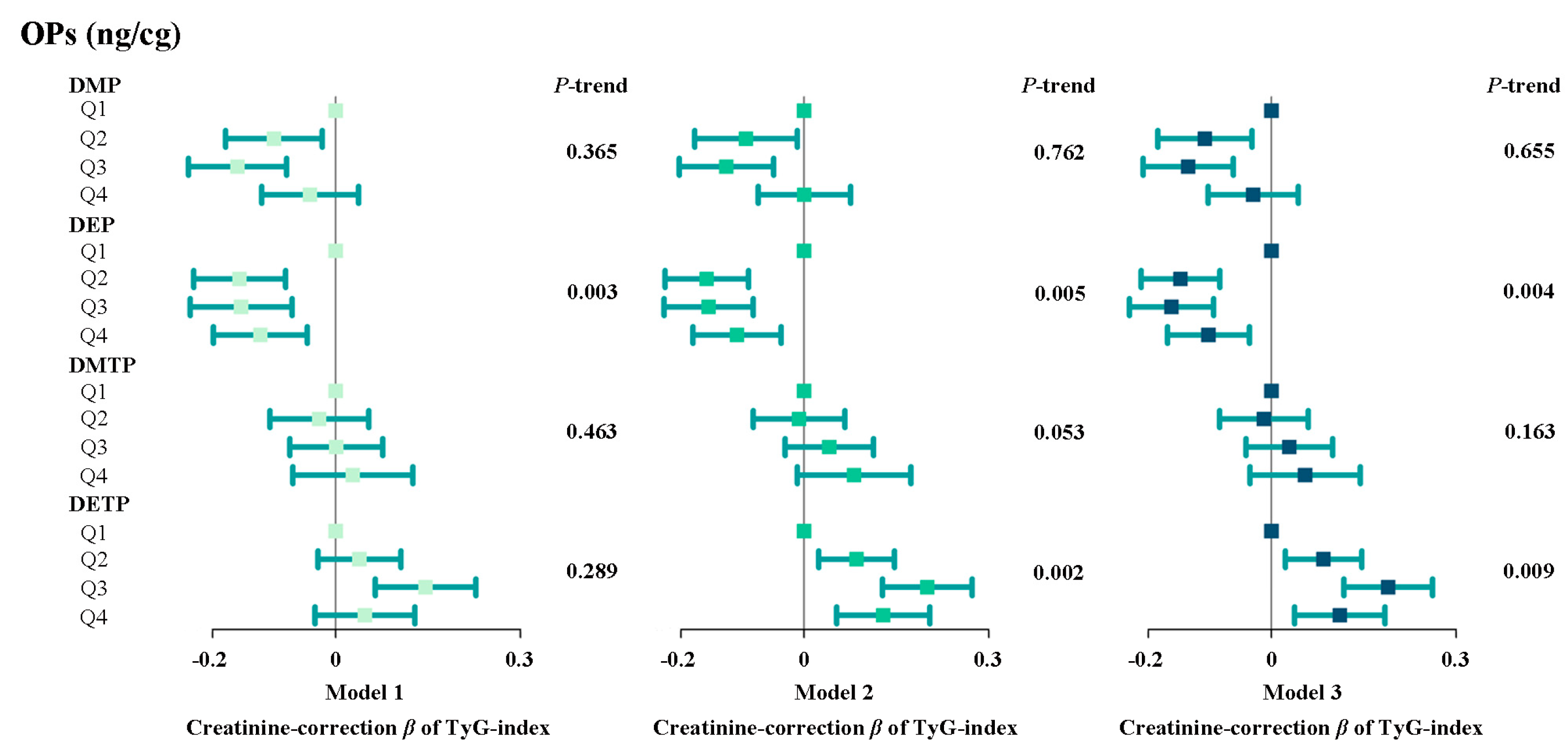

3.2. The Relationship Between Individual Urinary Metabolites of Organophosphate Pesticides and the Tyg Index

3.3. Dose–Response Curve Between Opp Metabolites and Tyg Index

3.4. The Relationship Between Mixtures of Urinary Organophosphate Pesticide Metabolites and the Tyg Index

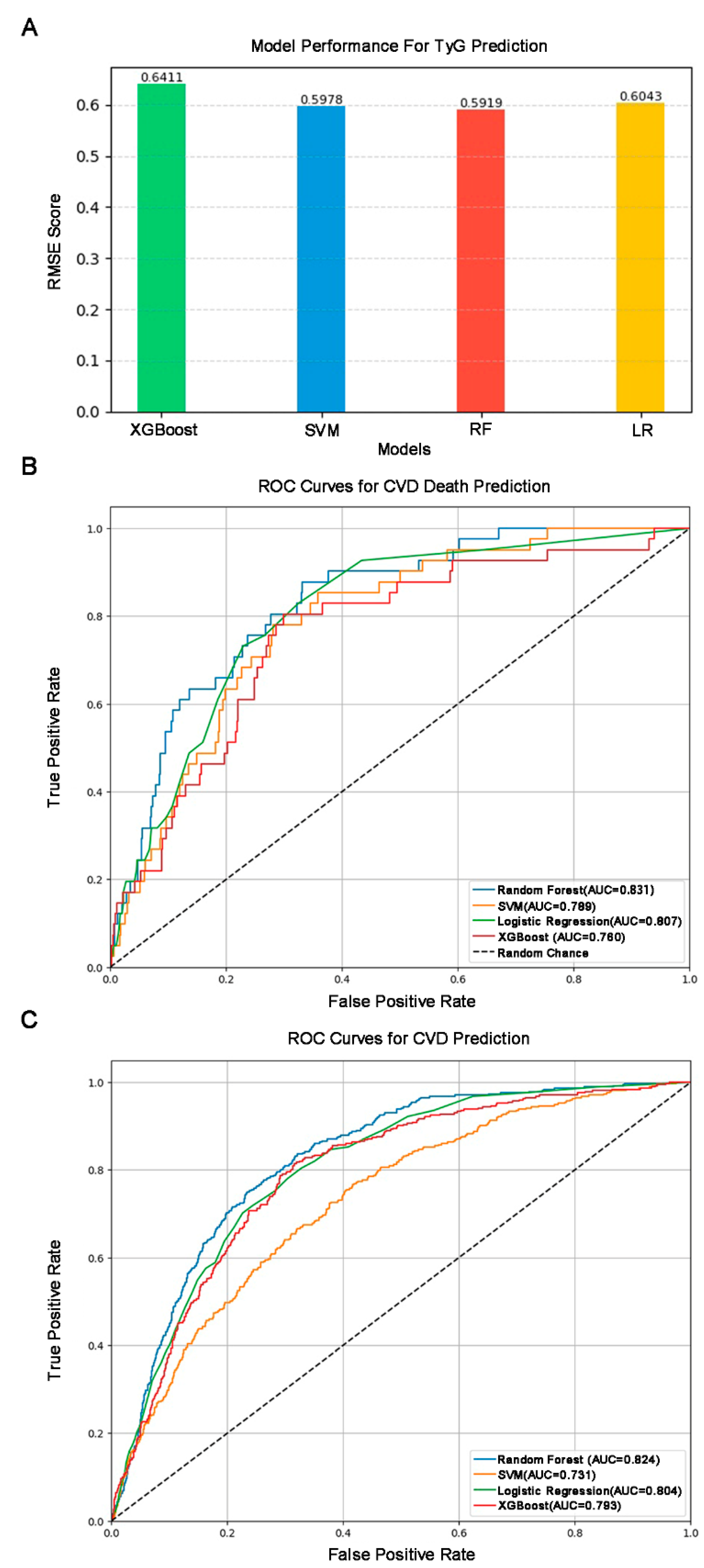

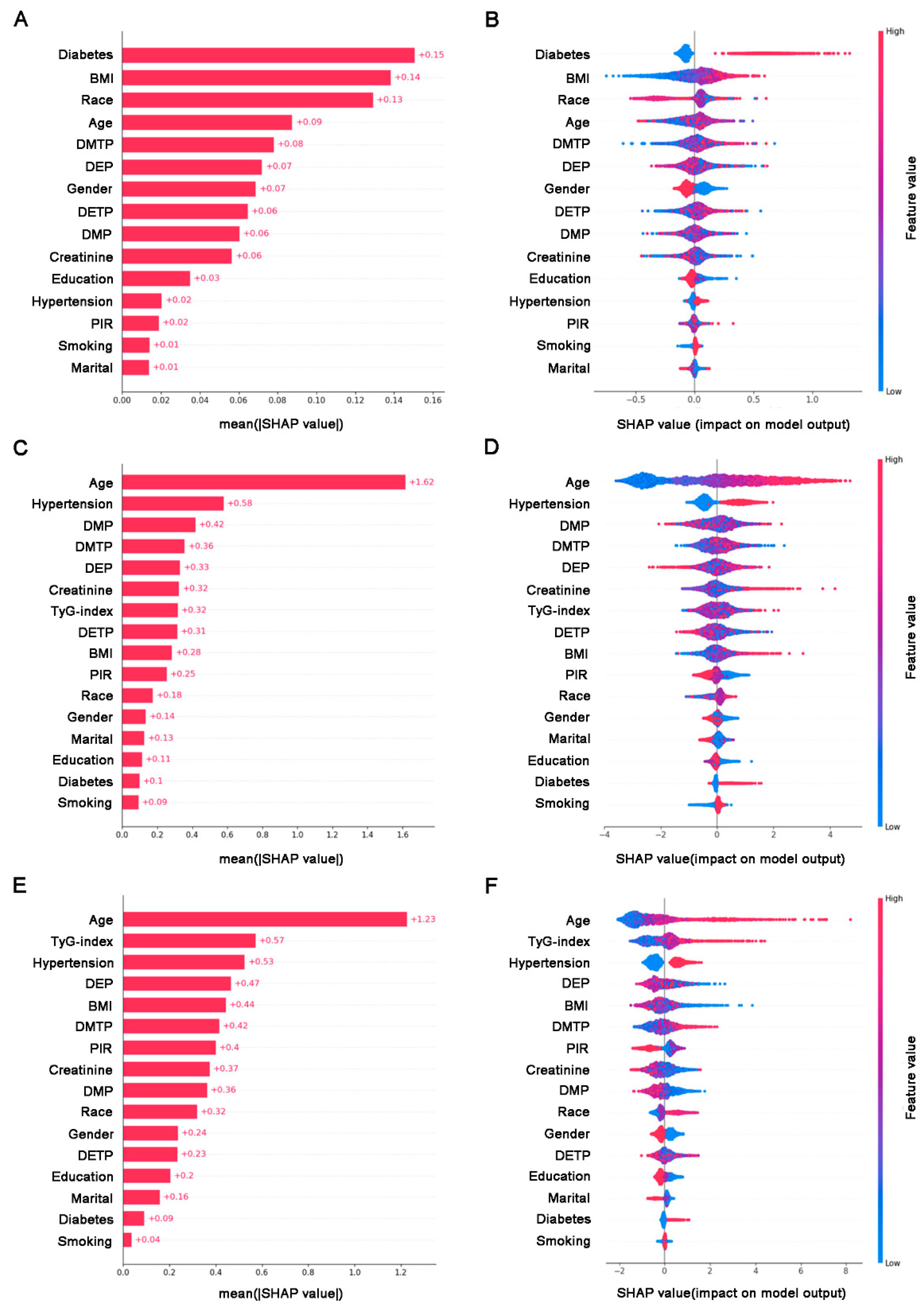

3.5. Model Construction and SHAP Interpretable Result

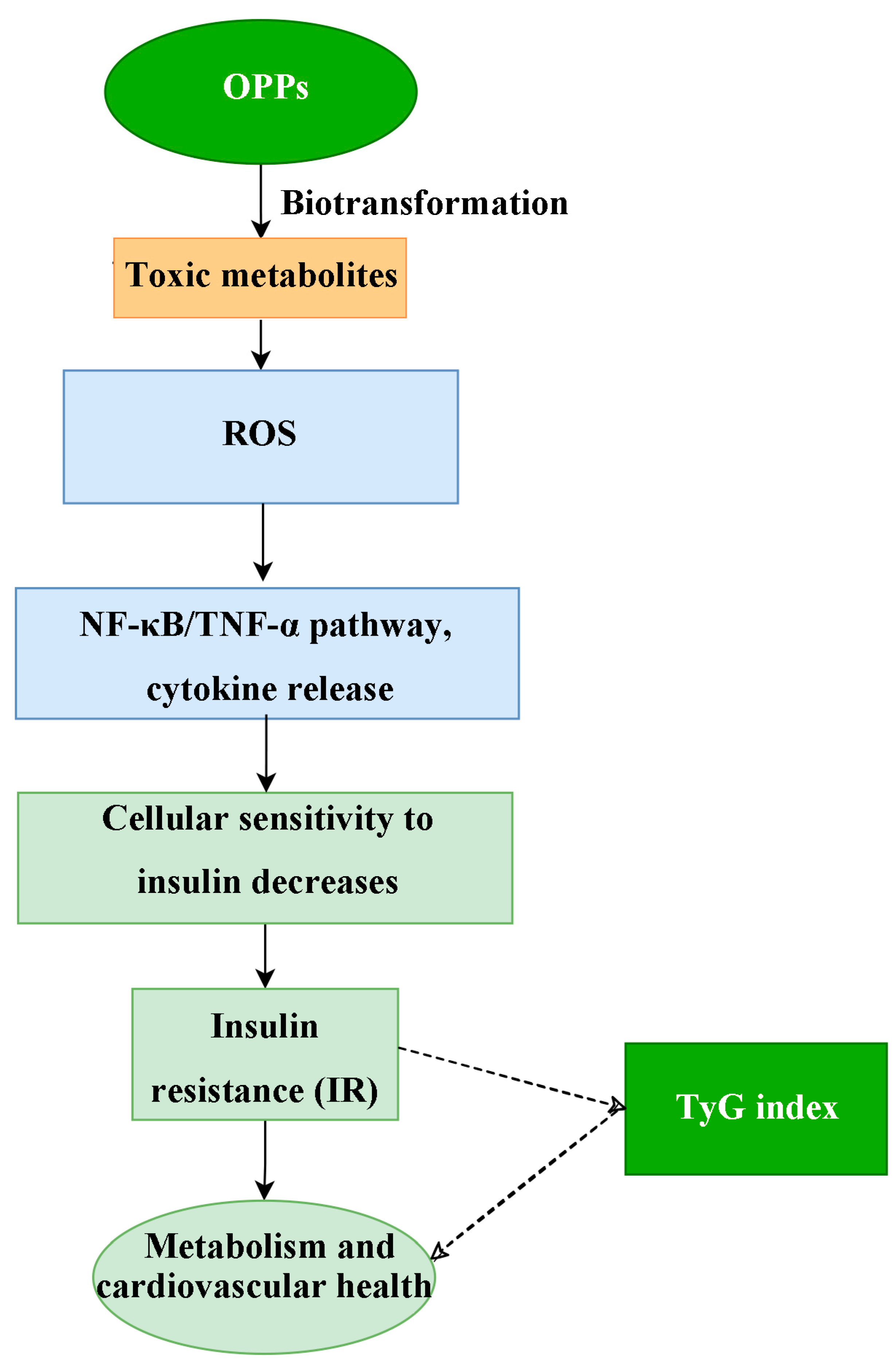

3.6. Details About Mechanisms and Targets

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Singh, B.K. Organophosphorus-degrading bacteria: Ecology and industrial applications. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009, 7, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, S.; Singh, B.; Dhingra, I.; Joshi, A.; Kodgire, P. Bioremediation and bioscavenging for elimination of organophosphorus threats: An approach using enzymatic advancements. Environ. Res. 2024, 252 Pt 2, 118888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisoni, G.B.; Altomare, D.; Thal, D.R.; Ribaldi, F.; van der Kant, R.; Ossenkoppele, R.; Blennow, K.; Cummings, J.; van Duijn, C.; Nilsson, P.M.; et al. The probabilistic model of Alzheimer disease: The amyloid hypothesis revised. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2022, 23, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perrin, L.; Spinosi, J.; Chaperon, L.; Kab, S.; Moisan, F.; Ebaz, A. Pesticides expenditures by farming type and incidence of Parkinson disease in farmers: A French nationwide study. Environ. Res. 2021, 197, 111161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-Mariano, J.Á.; Baltazar-Reyes, M.C.; Salazar-Martínez, E.; Cupul-Uicab, L.A. Exposure to the pesticide DDT and risk of diabetes and hypertension: Systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2022, 239, 113865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javeres, M.N.L.; Habib, R.; Laure, N.J.; Shah, S.T.A.; Valis, M.; Kuca, K.; Nurulain, S.M. Chronic Exposure to Organophosphates Pesticides and Risk of Metabolic Disorder in Cohort from Pakistan and Cameroon. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chao, M.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, W.; Xu, H.; Zhang, L.; Tao, Q.; Da, Q. Association between organophosphorus insecticides exposure and osteoarthritis in patients with arteriosclerotic cardiovascular disease. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rani, L.; Thapa, K.; Kanojia, N.; Sharma, N.; Singh, S.; Grewal, A.S.; Srivastav, A.L.; Kaushal, J. An extensive review on the consequences of chemical pesticides on human health and environment. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 283, 124657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.S.; Sharma, R.; Parween, T.; Patanjali, P.K. Pesticide Contamination and Human Health Risk Factor. In Modern Age Environmental Problems and their Remediation; 2018; pp. 49–68. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-64501-8_3 (accessed on 9 September 2024).

- Huo, D.; Jiang, S.; Qin, Z.; Feng, Y.; Yang, R.; Lv, L.; Li, Y. Omethoate induces pharyngeal cancer cell proliferation and G1/S cell cycle progression by activation of Akt/GSK-3β/cyclin D1 signaling pathway. Toxicology 2019, 427, 152298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Eryani, L.; Wahlang, B.; Falkner, K.C.; Guardiola, J.J.; Clair, H.B.; Prough, R.A.; Cave, M. Identification of Environmental Chemicals Associated with the Development of Toxicant-associated Fatty Liver Disease in Rodents. Toxicol. Pathol. 2015, 43, 482–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahlang, B.; Falkner, K.C.; Gregory, B.; Ansert, D.; Young, D.; Conklin, D.J.; Bhatnagar, A.; McClain, C.J.; Cave, M. Polychlorinated biphenyl 153 is a diet-dependent obesogen that worsens nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in male C57BL6/J mice. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2013, 24, 1587–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Chi, X.; Wang, Y.; Setrerrahmane, S.; Xie, W.; Xu, H. Trends in insulin resistance: Insights into mechanisms and therapeutic strategy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; San, W.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, S.; Cao, D.; Chen, Y.; Meng, G. Different types of cell death in diabetic endothelial dysfunction. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 168, 115802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancusi, C.; de Simone, G.; Best, L.G.; Wang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Roman, M.J.; Lee, E.T.; Howard, B.V.; Devereux, R.B. Myocardial mechano-energetic efficiency and insulin resistance in non-diabetic members of the Strong Heart Study cohort. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2019, 18, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boza, C.; Riquelme, A.; Ibañez, L.; Duarte, I.; Norero, E.; Viviani, P.; Soza, A.; Fernandez, J.I.; Raddatz, A.; Guzman, S.; et al. Predictors of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) in obese patients undergoing gastric bypass. Obes. Surg. 2005, 15, 1148–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Čolak, D.; Pintar, T.; Kučič, A.C.; Salobir, J.; Gašpirc, B. Periodontal and Hepatic Parameters in Obese Patients Undergoing Bariatric Surgery. Oral Health Prev. Dent. 2022, 20, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bedogni, G.; Bellentani, S.; Miglioli, L.; Masutti, F.; Passalacqua, M.; Castiglione, A.; Tiribelli, C. The Fatty Liver Index: A simple and accurate predictor of hepatic steatosis in the general population. BMC Gastroenterol. 2006, 6, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamroonkiadtikun, P.; Ananchaisarp, T.; Wanichanon, W. The triglyceride-glucose index, a predictor of type 2 diabetes development: A retrospective cohort study. Prim. Care Diabetes 2020, 14, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.M.; Lee, H.S.; Lee, Y.J.; Lee, J.H. The triglyceride-glucose index is a more powerful surrogate marker for predicting the prevalence and incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus than the homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2021, 180, 109042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, K.; Ahn, C.W.; Lee, S.B.; Kang, S.; Nam, J.S.; Lee, B.K.; Kim, J.H.; Park, J.S. Elevated TyG Index Predicts Progression of Coronary Artery Calcification. Diabetes Care 2019, 42, 1569–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, K.-B.; Park, E.J.; Han, D.; Lee, J.H.; Choi, S.-Y.; Chun, E.J.; Park, S.H.; Han, H.-W.; Sung, J.; Jung, H.O.; et al. Triglyceride glucose index is an independent predictor for the progression of coronary artery calcification in the absence of heavy coronary artery calcification at baseline. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2020, 19, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Q.; Zhang, T.-Y.; Cheng, Y.-J.; Ma, Y.; Xu, Y.-K.; Yang, J.-Q.; Zhou, Y.-J. Impacts of triglyceride-glucose index on prognosis of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome: Results from an observational cohort study in China. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2020, 19, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, R.; Wang, Z.; Chen, J.; Bao, X.; Xu, N.; Guo, S.; Gu, R.; Wang, W.; Wei, Z.; Wang, L. Prognostic value of triglyceride glucose (TyG) index in patients with acute decompensated heart failure. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2022, 21, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, W.; Xing, L.; Jing, L.; Tian, Y.; Yan, H.; Sun, Q.; Dai, D.; Shi, L.; Liu, S. Value of triglyceride-glucose index for the estimation of ischemic stroke risk: Insights from a general population. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2020, 30, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Wang, H.; Song, Q.; Li, N.; Liang, Q.; Su, W.; Liang, M.; Ding, X.; Sun, C.; Lowe, S.; et al. Association between exposure to organophosphorus pesticides and the risk of diabetes among US Adults: Cross-sectional findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Chemosphere 2022, 301, 134471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glover, F.; Mehta, A.; Richardson, M.; Muncey, W.; Del Giudice, F.; Belladelli, F.; Seranio, N.; Eisenberg, M.L. Investigating the prevalence of erectile dysfunction among men exposed to organophosphate insecticides. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2024, 47, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Xiao, S.; Jiao, X.; Shen, Y. The triglyceride-glucose index is a predictor for cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in CVD patients with diabetes or pre-diabetes: Evidence from NHANES 2001–2018. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2023, 22, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pei, H.; Li, S.; Su, X.; Lu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wu, S. Association between triglyceride glucose index and sleep disorders: Results from the NHANES 2005–2008. BMC Psychiatry 2023, 23, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, K.M.; Upson, K.; Buckley, J.P. Lipid and Creatinine Adjustment to Evaluate Health Effects of Environmental Exposures. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2017, 4, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Wang, Q. Association between organophosphorus insecticides exposure and the prevalence of sleep problems in the US adults: An analysis based on the NHANES 2007–2018. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 255, 114803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Wu, B.; Xia, W.; Gao, J.; Xie, P.; Feng, L.; Sun, C.; Liang, M.; Ding, X.; Zhao, D.; et al. Association of organophosphate ester exposure with cardiovascular disease among US adults: Cross-sectional findings from the 2011–2018 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Chemosphere 2022, 308 Pt 2, 136428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, K.; Wang, X.; Hu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, L.; Qi, X.; Liu, L.; Ming, Z.; Tao, X.; Li, Y. The association between triglyceride-glucose index and its combination with obesity indicators and cardiovascular disease: NHANES 2003–2018. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2024, 23, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SwissTargetPrediction. SwissDrugDesign. Available online: http://swisstargetprediction.ch (accessed on 9 September 2024).

- GeneCards. The Human Gene Database. Available online: https://www.genecards.org/ (accessed on 9 September 2024).

- STRING. Protein-Protein Interaction Networks Functional Enrichment Analysis. Available online: https://string-db.org/ (accessed on 9 September 2024).

- Bardou, P.; Mariette, J.; Escudié, F.; Djemiel, C.; Klopp, C. jvenn: An interactive Venn diagram viewer. BMC Bioinform. 2014, 15, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avagimyan, A.; Pogosova, N.; Fogacci, F.; Aghajanova, E.; Djndoyan, Z.; Patoulias, D.; Sasso, L.L.; Bernardi, M.; Faggiano, A.; Mohammadifard, N.; et al. Triglyceride-glucose index (TyG) as a novel biomarker in the era of cardiometabolic medicine. Int. J. Cardiol. 2025, 418, 132663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabipoorashrafi, S.A.; Seyedi, S.A.; Rabizadeh, S.; Ebrahimi, M.; Ranjbar, S.A.; Reyhan, S.K.; Meysamie, A.; Nakhjavani, M.; Esteghamati, A. The accuracy of triglyceride-glucose (TyG) index for the screening of metabolic syndrome in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2022, 32, 2677–2688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grundy, S.M.; Brewer Jr, H.B.; Cleeman, J.I.; Smith, S.C., Jr.; Lenfant, C. Definition of metabolic syndrome: Report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/American Heart Association conference on scientific issues related to definition. Circulation 2004, 109, 433–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hua, Y.Q.; Zeng, Y.; Xu, J.; Le Xu, X. Naringenin alleviates nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in middle-aged Apoe(-/-)mice: Role of SIRT1. Phytomedicine 2021, 81, 153412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Chao, J.; Zhang, N.; Wu, Y.; Bao, M.; Yan, C.; Chen, T.; Li, X.; Chen, Y. A national study exploring the association between triglyceride-glucose index and risk of hyperuricemia events in adults with hypertension. Prev. Med. Rep. 2024, 43, 102763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alberti, K.G.; Zimmet, P.Z. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabet. Med. 1998, 15, 539–553. [Google Scholar]

- Seesen, M.; Pratchayasakul, W.; Pintana, H.; Chattipakorn, N.; Chattipakorn, S.C. Exposure to organophosphates in association with the development of insulin resistance: Evidence from in vitro, in vivo, and clinical studies. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2022, 168, 113389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Ji, H.; Sun, W.; An, X.; Lian, F. Triglyceride glucose (TyG) index: A promising biomarker for diagnosis and treatment of different diseases. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2025, 131, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ou, J.; Xian, R.; Li, J.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, K.; Mo, P.; Fang, J.; Shen, Y.; Hu, X.; Fang, S.; et al. Associations of dichlorophenols, trichlorophenols, and ortho-phenylphenol with the risk and prognosis of diabetes and prediabetes: A population-based study. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 277, 116345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Y.; Xu, W.; Liu, S.; Xu, Z.; Qiao, S.; Cai, Y. Serum albumin and liver dysfunction mediate the associations between organophosphorus pesticide exposure and hypertension among US adults. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 948, 174748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhao, L.; Zhou, X.; Meng, X.; Zhou, X. Role of inflammation, immunity, and oxidative stress in hypertension: New insights and potential therapeutic targets. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1098725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toh, B.-H.; Bobik, A.; Kyaw, T.S.; Drummond, G.; Sobey, C.G.; Guzik, T.J. Immune mechanisms in vascular disease and stroke. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 730691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alipanah, H.; Doraghi, H.K.; Sayadi, M.; Nematollahi, A.; Hekmat, A.S.; Nejati, R. Subacute toxicity of chlorpyrifos on histopathological damages, antioxidant activity, and pro-inflammatory cytokines in the rat model. Environ. Toxicol. 2022, 37, 880–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weis, G.C.C.; Assmann, C.E.; Mostardeiro, V.B.; Alves, A.d.O.; da Rosa, J.R.; Pillat, M.M.; de Andrade, C.M.; Schetinger, M.R.C.; Morsch, V.M.M.; da Cruz, I.B.M.; et al. Chlorpyrifos pesticide promotes oxidative stress and increases inflammatory states in BV-2 microglial cells: A role in neuroinflammation. Chemosphere 2021, 278, 130417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, J.; Deng, S.; Fu, H.; Yang, Q.; Ren, F.; Zeng, S.; Chen, Z.; Yang, Y.; Wu, Z. Chlorpyrifos induces placental oxidative stress and barrier dysfunction by inducing mitochondrial apoptosis through the ERK/MAPK signaling pathway: In vitro and in vivo studies. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 903, 166449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Shao, B.; Wang, J.; Shen, Z.; Liu, H.; Li, S. Chlorpyrifos caused necroptosis via MAPK/NF-κB/TNF-α pathway in common carp (Cyprinus carpio L.) gills. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2021, 249, 109126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alruhaimi, R.S. Betulinic acid protects against cardiotoxicity of the organophosphorus pesticide chlorpyrifos by suppressing oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis in rats. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2023, 30, 51180–51190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freyre, E.O.; Valencia, A.T.; Guzmán, D.D.; Maldonado, I.C.; Ledezma, L.E.B.; Carrillo, M.F.Z.; Escorza, M.A.Q. Oxidative Stress as a Molecular Mechanism of Exposure to Organophosphorus Pesticides: A Review. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2021, 22, 890–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sule, R.O.; Condon, L.; Gomes, A.V. A Common Feature of Pesticides: Oxidative Stress-The Role of Oxidative Stress in Pesticide-Induced Toxicity. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 5563759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; An, X.; Yang, C.; Sun, W.; Ji, H.; Lian, F. The crucial role and mechanism of insulin resistance in metabolic disease. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1149239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchernof, A.; Després, J.P. Pathophysiology of human visceral obesity: An update. Physiol. Rev. 2013, 93, 359–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coker, R.H.; Williams, R.H.; Yeo, S.E.; Kortebein, P.M.; Bodenner, D.L.; Kern, P.A.; Evans, W.J. Visceral fat and adiponectin: Associations with insulin resistance are tissue-specific in women. Metab. Syndr. Relat. Disord. 2009, 7, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbasi, F.; Reaven, G.M. Comparison of two methods using plasma triglyceride concentration as a surrogate estimate of insulin action in nondiabetic subjects: Triglycerides × glucose versus triglyceride/high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Metabolism 2011, 60, 1673–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-García, A.; Rodríguez-Gutiérrez, R.; Mancillas-Adame, L.; González-Nava, V.; Díaz González-Colmenero, A.; Solis, R.C.; Alvarez-Villalobos, N.A.; González-González, J.G. Diagnostic Accuracy of the Triglyceride and Glucose Index for Insulin Resistance: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2020, 2020, 4678526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, J.; Ruan, X.; Liu, W.; Liu, X.; Wu, K.; Qiu, H.; Wang, X.; Ding, Y.; Tan, X.; Li, Z.; et al. Prospective cohort studies underscore the association of abnormal glycemic measures with all-cause and cause-specific mortalities. iScience 2024, 27, 110233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muzurović, E.; Mikhailidis, D.P.; Mantzoros, C. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome and their association with vascular risk. Metabolism 2021, 119, 154770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Xu, L.; Wu, M.; Chen, S.; Wang, Y.; Tian, Y. Association between triglyceride-glucose index and risk of arterial stiffness: A cohort study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2021, 20, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzegar, N.; Tohidi, M.; Hasheminia, M.; Azizi, F.; Hadaegh, F. The impact of triglyceride-glucose index on incident cardiovascular events during 16 years of follow-up: Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2020, 19, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simental-Mendía, L.E.; Hernández-Ronquillo, G.; Gómez-Díaz, R.; Rodríguez-Morán, M.; Guerrero-Romero, F. The triglycerides and glucose index is associated with cardiovascular risk factors in normal-weight children and adolescents. Pediatr. Res. 2017, 82, 920–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xuan, X.; Hamaguchi, M.; Cao, Q.; Okamura, T.; Hashimoto, Y.; Obora, A.; Kojima, T.; Fukui, M.; Yuan, G.; Guo, Z.; et al. U-shaped association between the triglyceride-glucose index and the risk of incident diabetes in people with normal glycemic level: A population-base longitudinal cohort study. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 1555–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, J.; Wang, A.; Liu, G.; Wang, M.; Zuo, Y.; Li, W.; Zhai, Q.; Mu, Y.; Gaisano, H.Y.; He, Y.; et al. Elevated triglyceride-glucose (TyG) index predicts incidence of Prediabetes: A prospective cohort study in China. Lipids Health Dis. 2020, 19, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Hao, J.; He, X.; Wang, C.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, L.; Ren, L. Association Between Triglyceride-Glucose Index and Serum Uric Acid Levels: A Biochemical Study on Anthropometry in Non-Obese Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2022, 15, 3447–3458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahapary, D.L.; Pratisthita, L.B.; Fitri, N.A.; Marcella, C.; Wafa, S.; Kurniawan, F.; Rizka, A.; Tarigan, T.J.E.; Harbuwono, D.S.; Purnamasari, D.; et al. Challenges in the diagnosis of insulin resistance: Focusing on the role of HOMA-IR and Tryglyceride/glucose index. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2022, 16, 102581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| TyG Index Quartile | Total | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 4429 | 1106 | 1109 | 1107 | 1107 | |

| Gender (%) a | <0.001 | |||||

| Male | 2183 (49.3) | 441 (39.9) | 541 (48.8) | 579 (52.3) | 622 (56.2) | |

| Female | 2246 (50.7) | 665 (60.1) | 568 (51.2) | 528 (47.7) | 485 (43.8) | |

| Age (years) group (%) a | <0.001 | |||||

| 20–39 | 1480 (33.4) | 541 (48.9) | 382 (34.4) | 307 (27.7) | 250 (22.6) | |

| 40–59 | 1571 (35.5) | 354 (32.0) | 374 (33.7) | 400 (36.1) | 443 (40.0) | |

| ≥60 | 1378 (31.1) | 211 (19.1) | 353 (31.8) | 400 (36.1) | 414 (37.4) | |

| Education level (%) a | <0.001 | |||||

| Below high school | 1068 (24.1) | 196 (17.7) | 241 (21.7) | 290 (26.2) | 341 (30.8) | |

| High school | 989 (22.3) | 222 (20.1) | 263 (23.7) | 250 (22.6) | 254 (22.9) | |

| Above high school | 2372 (53.6) | 688 (62.2) | 605 (54.6) | 567 (51.2) | 512 (46.3) | |

| Marital status (%) a | <0.001 | |||||

| Married/living with partner | 2675 (60.4) | 605 (54.7) | 649 (58.5) | 720 (65.0) | 701 (63.3) | |

| Widowed/divorced/separated/ | 980 (22.1) | 218 (19.7) | 252 (22.7) | 242 (21.9) | 268 (24.2) | |

| Never married | 774 (17.5) | 283 (25.6) | 208 (18.8) | 145 (13.1) | 138 (12.5) | |

| Race (%) a | <0.001 | |||||

| Mexican American | 682 (15.4) | 104 (9.4) | 165 (14.9) | 186 (16.8) | 227 (20.5) | |

| Other Hispanic | 376 (8.5) | 77 (7.0) | 77 (6.9) | 117 (10.6) | 105 (9.5) | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 1897 (42.8) | 394 (35.6) | 495 (44.6) | 495 (44.7) | 513 (46.3) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1008 (22.8) | 410 (37.1) | 262 (23.6) | 193 (17.4) | 143 (12.9) | |

| Other race | 466 (10.5) | 121 (10.9) | 110 (9.9) | 116 (10.5) | 119 (10.7) | |

| Household income (%) a | 0.265 | |||||

| ≤1.3 PIR | 1321 (29.8) | 309 (27.9) | 335 (30.2) | 318 (28.7) | 359 (32.4) | |

| 1.3–3.5 PIR | 1681 (38.0) | 417 (37.7) | 425 (38.3) | 428 (38.7) | 411 (37.1) | |

| >3.5 PIR | 1427 (32.2) | 380 (34.4) | 349 (31.5) | 361 (32.6) | 337 (30.4) | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2), (median (25th, 75th)) b | 28.22 (24.50, 32.70) | 25.63 (22.41, 30.20) | 27.79 (24.15, 32.02) | 28.91 (25.53, 33.21) | 30.00 (26.60, 34.19) | <0.001 |

| Smoking (%) a | 3318 (74.8) | 815 (73.7) | 850 (76.6) | 816 (73.7) | 837 (75.6) | 0.285 |

| Hypertension (%) a | 1613 (36.4) | 282 (25.5) | 377 (34.0) | 424 (38.3) | 530 (47.9) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes (%) a | 582 (13.1) | 39 (3.5) | 89 (8.0) | 125 (11.3) | 329 (29.7) | <0.001 |

| Cardiovascular diseases (%) a | 502 (11.3) | 81 (7.3) | 132 (11.9) | 125 (11.3) | 164 (14.8) | <0.001 |

| Creatinine-adjusted urinary OPs (ng/cg), (median (25th, 75th)) b | ||||||

| DMP | 11.57 (3.80, 35.94) | 11.41 (4.36, 30.05) | 12.02 (3.93, 35.34) | 11.49 (3.69, 37.05) | 11.48 (3.55, 39.44) | <0.001 |

| DEP | 13.73 (3.49, 34.28) | 15.27 (5.52, 34.87) | 14.35 (3.48, 33.51) | 12.80 (2.91, 33.93) | 11.95 (2.80, 34.43) | <0.001 |

| DMTP | 9.97 (3.72, 30.22) | 8.18 (3.38, 22.78) | 9.59 (3.61, 30.07) | 10.42 (3.85, 34.22) | 12.30 (4.33, 35.24) | <0.001 |

| DETP | 2.76 (1.21, 6.34) | 2.32 (1.04, 5.58) | 2.69 (1.19, 6.21) | 2.83 (1.24, 6.46) | 3.22 (1.48, 6.84) | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, X.; Tian, M.; Shen, Z.; Tian, K.; Fei, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Ruan, J.; Mo, S.; Dai, J.; Xia, W.; et al. Comprehensive Cross-Sectional Study of the Triglyceride Glucose Index, Organophosphate Pesticide Exposure, and Cardiovascular Diseases: A Machine Learning Integrated Approach. Toxics 2025, 13, 118. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13020118

Wang X, Tian M, Shen Z, Tian K, Fei Y, Cheng Y, Ruan J, Mo S, Dai J, Xia W, et al. Comprehensive Cross-Sectional Study of the Triglyceride Glucose Index, Organophosphate Pesticide Exposure, and Cardiovascular Diseases: A Machine Learning Integrated Approach. Toxics. 2025; 13(2):118. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13020118

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Xuehai, Mengxin Tian, Zengxu Shen, Kai Tian, Yue Fei, Yulan Cheng, Jialing Ruan, Siyi Mo, Jingjing Dai, Weiyi Xia, and et al. 2025. "Comprehensive Cross-Sectional Study of the Triglyceride Glucose Index, Organophosphate Pesticide Exposure, and Cardiovascular Diseases: A Machine Learning Integrated Approach" Toxics 13, no. 2: 118. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13020118

APA StyleWang, X., Tian, M., Shen, Z., Tian, K., Fei, Y., Cheng, Y., Ruan, J., Mo, S., Dai, J., Xia, W., Jiang, M., Zhao, X., Zhu, J., & Xiao, J. (2025). Comprehensive Cross-Sectional Study of the Triglyceride Glucose Index, Organophosphate Pesticide Exposure, and Cardiovascular Diseases: A Machine Learning Integrated Approach. Toxics, 13(2), 118. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13020118