3.1. The Content of Se and Other Trace Elements in the Surface Soil

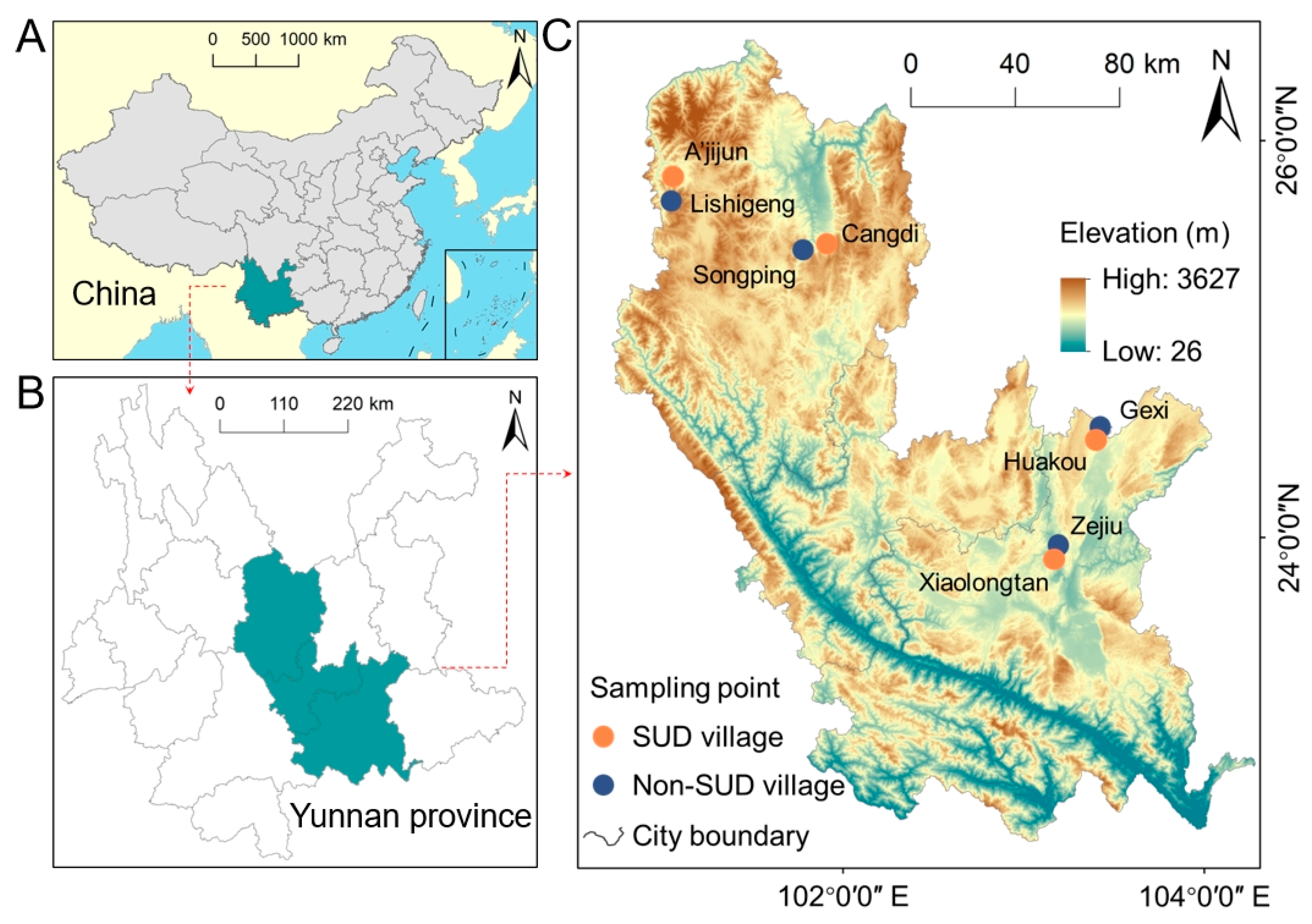

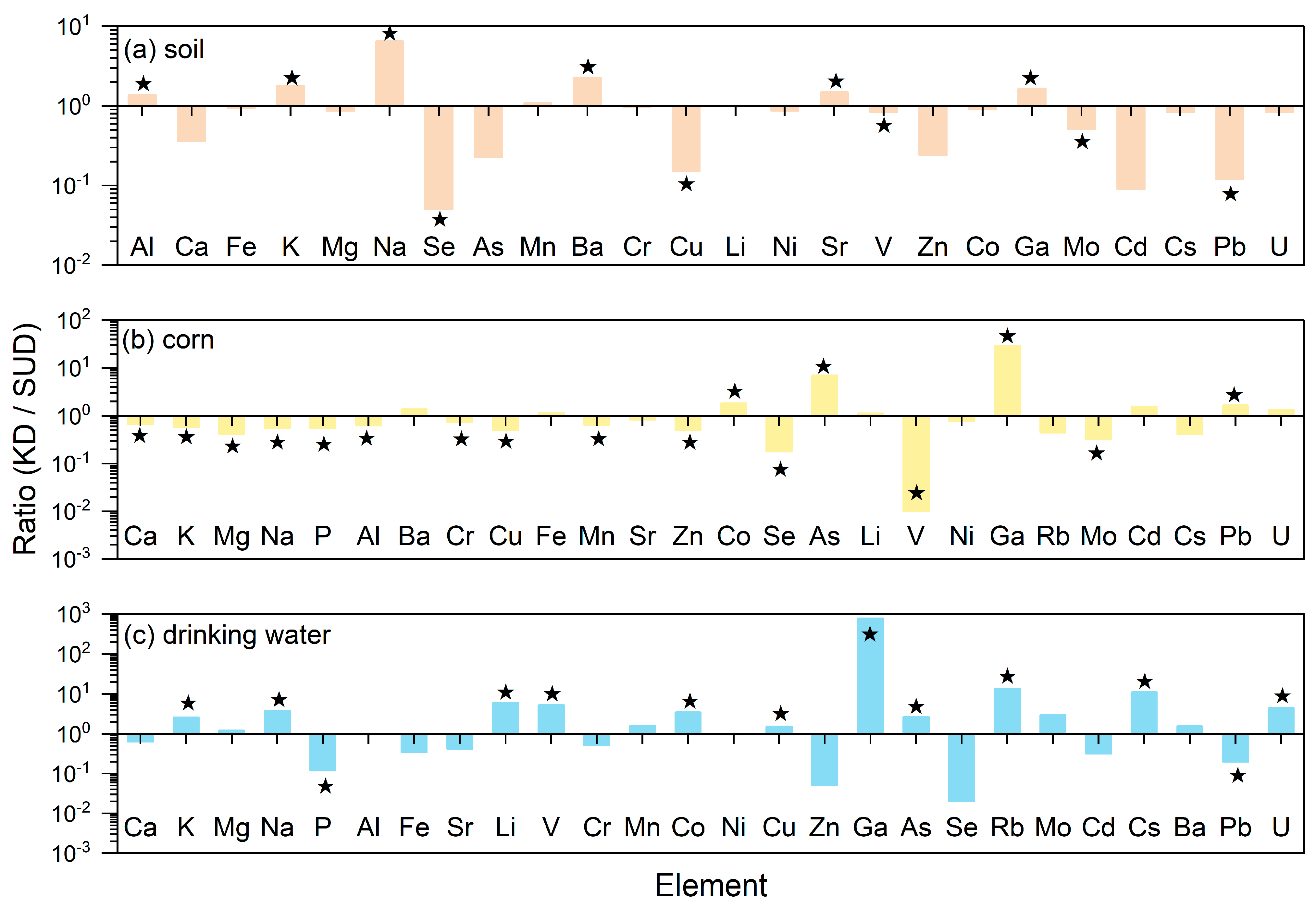

The comparison results of soil element concentrations in the four SUD villages within the SUD area of Yunnan Province with the national background values of soil elements are presented in

Figure 2a and

Table 3. The study found that the concentrations of Cu, V, and Cd in the soil of the four SUD villages were all higher than the national background values of soil elements, while the concentrations of Na and Ba were all lower than the national background values [

24]. Among them, the concentration of Cd in all the SUD villages was 1.70–121.63 times the national soil background value, followed by Cu (1.17–13.28 times). This might be due to the increase in human activities (such as mining, smelting, fertilizers, pesticides, and fuel combustion) over the past few decades, which led to the accumulation of these elements in the soil [

25,

26]. The concentrations of soil elements indicated by different letters in

Table 3 showed significant differences among the four SUD villages (

p < 0.05). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) revealed that Al, K and Cs showed significant differences across all SUD villages, while other elements exhibited significant variations between specific SUD villages (

p < 0.05), indicating considerable overall heterogeneity. Among them, the coefficients of variation of all elements (except V) among the four SUD villages were all higher than 20%, and the coefficients of variation of Se, As, Cu, Zn, Cd and Pb exceeded 100%. This indicates that the element concentrations in the soil of the SUD villages vary significantly due to different geographical locations. Similar results can also be obtained from the maximum and minimum values of the same element in the four SUD villages, that is, the concentrations of Se, As, Cu, Zn, Cd and Pb in the four SUD villages can differ by more than ten times at most. To sum up, there are significant differences (e.g., Se, As, Cu, Zn, Cd and Pb) in soil element concentrations among different diseased villages in the SUD areas in Yunnan Province.

The comparison results of soil element concentrations in the four non-SUD villages within the SUD area of Yunnan Province with the national background values of soil elements are presented in

Figure 2b and

Table 4. The study found that the concentrations of As, Li, V, and Cd in the soil of the four non-SUD villages were all higher than the national background values of soil elements, while the concentrations of Na and Cr were all lower than the national background values [

24]. Among them, the concentration of Cd in all the non-SUD villages was 1.02–4.44 times the national soil background value, followed by As (1.19–2.94 times). Similarly to the studies on SUD villages, this might be due to the increase in human activities (such as mining, smelting, fertilizer production, pesticide use, and fuel combustion) over the past few decades, which has led to the accumulation of these elements in the soil [

25,

26]. The concentrations of soil elements indicated by different letters in

Table 4 show significant differences among the four non-SUD villages (

p < 0.05). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) revealed that K, Na, Ba, Cu, Sr, and Zn showed significant differences across all non-SUD villages, while other elements exhibited significant variations between specific non-SUD villages (

p < 0.05), indicating considerable overall heterogeneity. Among them, the coefficients of variation of all elements (except Fe, Cr, Li and V) among the four non-SUD villages were all higher than 20%, and the coefficients of variation of Ca, Se and Sr exceeded 100%. This indicates that the element concentrations in the soil of the non-SUD villages vary significantly due to different geographical locations. Similar results can also be obtained from the maximum and minimum values of the same element in the four non-SUD villages; that is, the concentrations of Ca, Se, Cu and Sr in the four non-SUD villages can differ by more than 26 times at most. To sum up, there are significant differences (e.g., Ca, Se, Cu and Sr) in soil element concentrations among different non-SUD villages in the SUD areas in Yunnan Province.

The

t-test results of the average concentrations of soil elements in non-SUD and SUD villages in the SUD areas of Yunnan Province are listed in

Table S5. It can be seen from

Table S5 that there are significant differences in Al, Na, Cr, Cu, Li, V, Mo and Cd in the soil between SUD villages and non-SUD villages (

p < 0.05). In addition, the comparison results of soil element concentrations between the four non-SUD villages and the SUD villages in the SUD area of Yunnan Province are presented in

Figure 2c. The research found that the Cr concentration in the four SUD villages was higher than that in the non-SUD villages, while the concentrations of Al, Na, V and Cs in the four SUD villages were all lower than those in the non-SUD villages. In addition, the concentrations of Ca, Se, Ba, Zn and Cd in Songping village are higher than those in Cangdi village. The concentrations of Fe, Mg, As, Mn, Cu, Co and Pb in Lishigeng village and Songping village were higher than those in A’jiju village and Cangdi village, respectively. The concentrations of K and Ni in Songping village and Gexi village were higher than those in Cangdi village and Huakou village, respectively. However, the concentrations of Li, Sr and Ga in the Zejiu village were lower than those in Xiaolongtan village, the concentration of Mo in Gexi village was lower than that in Huakou village, and the concentration of U in Lishigeng village was lower than that in A’jiju village. It is noteworthy that the Se concentrations in A’jiju village (0.10 mg/kg), Huazhu village (3.11 mg/kg), and Xiaolongtan village (0.30 mg/kg) were all higher than those in the neighboring non-SUD villages (Lishigeng village: 0.06 mg/kg, Gexi village: 1.41 mg/kg, and Zejiu village: 0.08 mg/kg). Only Cangdi village (0.0416 mg/kg) had a slightly lower Se concentration than the neighboring non-SUD villages (Gexi village: 0.0419 mg/kg). Therefore, Se deficiency in soil is not a common characteristic in SUD villages and non-SUD villages in the SUD area of Yunnan Province. Instead, the soil concentrations of Al, Na, V, and Cs in SUD village were lower than those in non-SUD villages, and especially the deficiency of Na (lower than the national soil background value) is an important characteristic of the SUD villages in the SUD area of Yunnan Province.

3.2. The Content of Se and Other Trace Elements in Corn

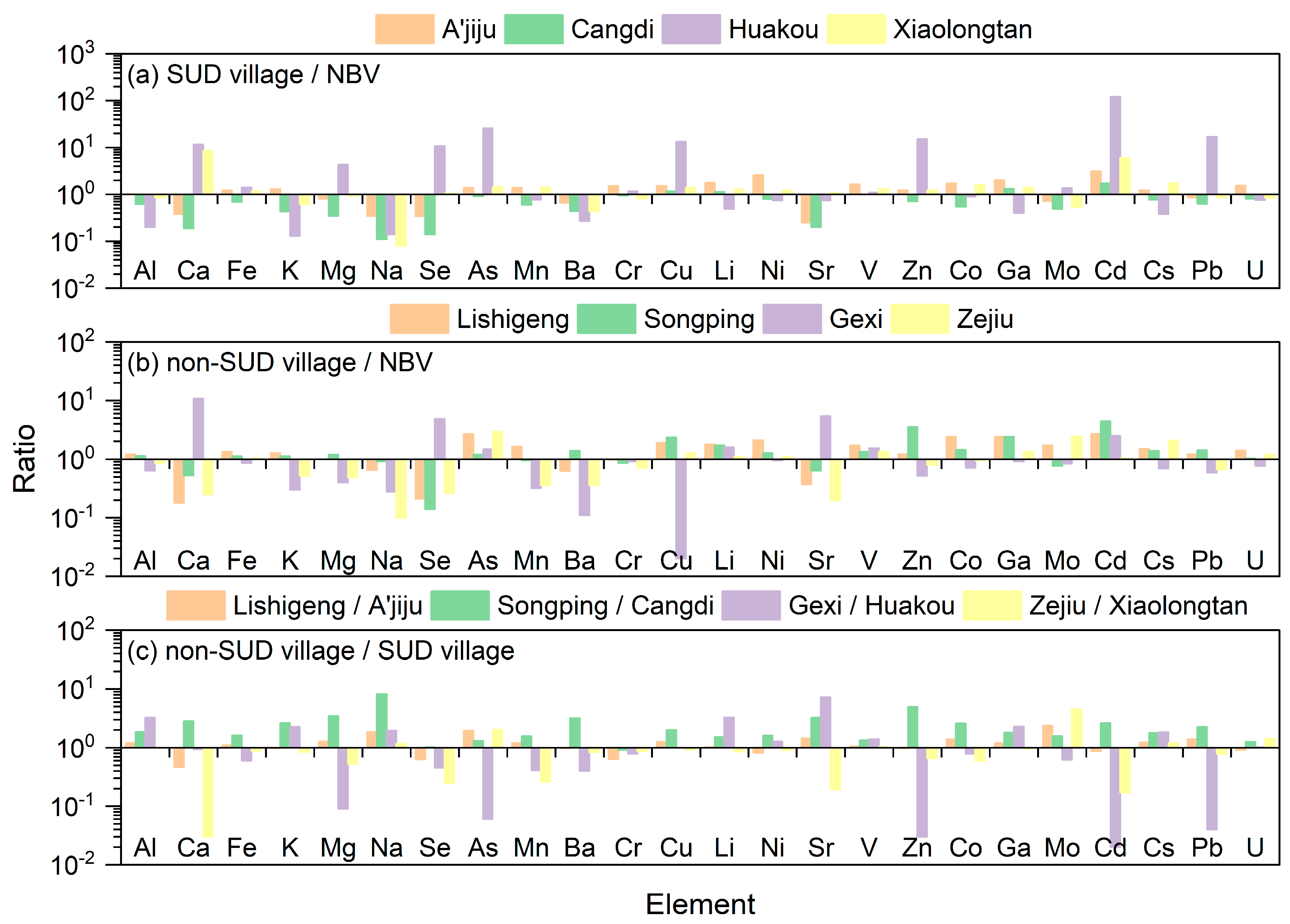

By comparing and analyzing the element concentrations of corn in four SUD villages with the food safety limit standards for elements (

Figure 3a and

Table 5), it was found that the concentrations of 8 elements (Cr, Cu, Zn, Se, As, Ni, Cd, and Pb) were all within the limit standards. Theoretically, these corns can be consumed by residents as safe agricultural products [

27,

28]. Among them, the concentrations of As and Se were far lower than the limit standards, ranging from 0.00 to 0.005 times and 0.014 to 0.054 times the limit standards, respectively. The concentrations of Cr and Zn were the closest to the limit standards, ranging from 0.51 to 0.88 and 0.26 to 0.44 times the limit standards, respectively. The element concentrations of corn indicated by different letters in

Table 5 showed significant differences among the four SUD villages (

p < 0.05). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) revealed that there were no significant differences in Ba and Sr among the four diseased villages in corn, while there were significant differences in K and P among the four diseased villages (

p < 0.05). However, there were significant differences in other elements among the diseased villages (

p < 0.05). Among these four SUD villages, the concentration differences of Cs and Rb were the greatest, with the maximum differences reaching 197.19 times and 31.11 times, respectively. Next were Ni (9.04 times) and Li (5.22 times), while the concentrations of other elements all had differences below 5 times.

By comparing and analyzing the element concentrations of corn in four non-SUD villages with the food safety limit standards for elements (

Figure 3b and

Table 6), it was also found that the concentrations of 8 elements (Cr, Cu, Zn, Se, As, Ni, Cd, and Pb) were all within the limit standards. Theoretically, these corns can also be consumed by residents as safe agricultural products [

27,

28]. Similarly to the research results of the SUD village, the concentrations of As and Se were far lower than the limit standards, ranging from 0.00 to 0.01 times and 0.00 to 0.06 times the limit standards, respectively. The concentrations of Cr and Zn were the closest to the limit standards, ranging from 0.44 to 0.62 and 0.29 to 0.44 times the limit standards, respectively. The element concentrations of corn indicated by different letters in

Table 6 showed significant differences among the four non-SUD villages (

p < 0.05). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) revealed that there were no significant differences in Cr among the four non-SUD villages in corn, while there were significant differences in K, Al, As and Mo among the four non-SUD villages (

p < 0.05). However, there were significant differences in other elements among the non-SUD villages (

p < 0.05). Among these four non-SUD villages, the concentration differences in Al were the greatest, with the maximum differences reaching 20.22 times, next were Cs (12.97 times) Cd (11.52 times) and Ba (7.41 times), while the concentrations of other elements all had differences below 5 times.

The

t-test results of the average concentrations of corn elements in non-SUD and SUD villages in the SUD areas of Yunnan Province are listed in

Table S6. It can be seen from

Table S6 that there are significant differences in K, Mg, Al, Co, Se, As and Ni in the corn between SUD villages and non-SUD villages (

p < 0.05). In addition, the comparison results of corn element concentrations between the four non-SUD villages and the SUD villages in the SUD area of Yunnan Province are presented in

Figure 3c. The research found that the concentrations of Ca, K, Mg, P, Ba, Cu, Mn, Sr, Zn, Co, Ni, Rb and Cs in Lishigeng village were higher than those in A’jigu village. The concentrations of Na, Ba, Cr, Zn, Co, As, Li, Rb, Cs and Pb in Songping village are higher than those in Cangdi village. The concentrations of Cu, Fe, Co, Se, As, V, Ni and Cd in Gexi village are higher than those in Huakou village. The concentrations of Ca, Na, Al, Ba, Cu, Sr, Co, As, V, Ga, Mo, Cd, Pb and U in the Zejiu village were higher than those in Xiaolongtan village. The Ni concentration in Lishigeng village and A’jiju village differs by 6.27 times, while the differences in other elements are all less than 3 times. The Co and Ni in Songping village and Cangdi village differ by 14.06 times and 5.95 times, respectively, while the differences in other elements are less than 3 times. The concentrations of Co and Cd in Gexi village and Huakou village differed by 5.00 times and 2.48 times, respectively, while the concentrations of other elements differed by less than 2 times. The concentrations of Co, Cd and U in Zejiu village and Xiaolongtan village differed by 5.88 times, 3.15 times and 3.03 times, respectively. In summary, although the deficiency of Se in corn is a common feature in both SUD and non-SUD villages in the SUD area of Yunnan Province, the Se content in corn from SUD villages is higher than that from non-SUD villages. However, corn from SUD villages is more deficient in Co than that from non-SUD villages. Co is a metal component of vitamin B

12, and Co deficiency leads to a reduction in the availability of B

12, thereby increasing health problems related to B

12 deficiency, such as anemia and nerve damage [

29,

30]. In addition, the concentrations of Co in the corn of the SUD village are also lower than those in some longevity regions (such as Jinxiang County in Shandong) and the Kaschin-Beck disease area (such as Yongshou County in Shaanxi) [

19,

31]. Therefore, the Co deficiency in corn from affected villages may pose additional health risks to local residents.

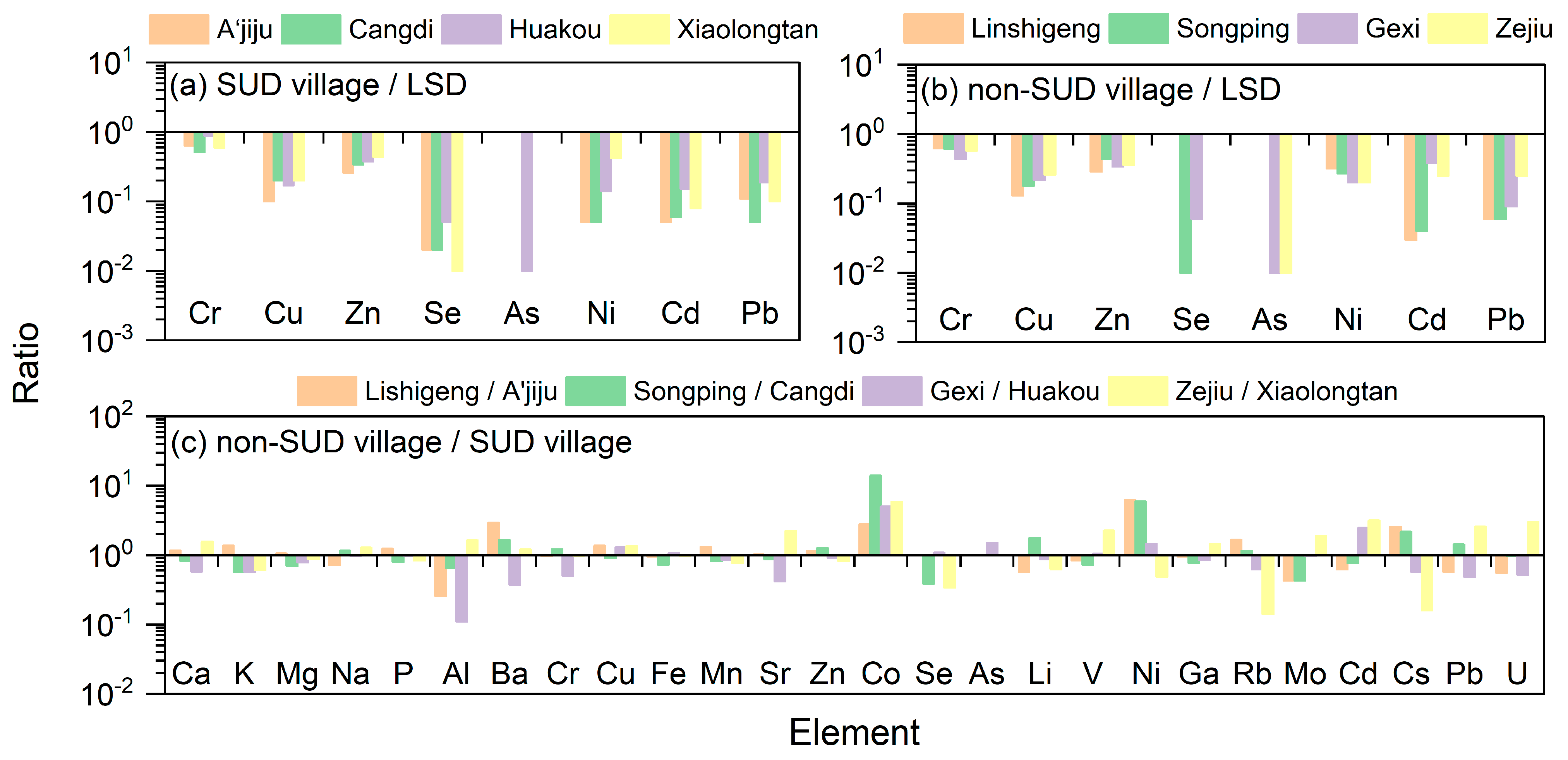

3.3. The Content of Se and Other Trace Elements in Water

By comparing and analyzing the element concentrations in drinking water from two SUD villages (Huakou village and Xiaolongtan village, where no drinking water was collected) with the drinking water hygiene standards of China and the WHO (

Figure 4a and

Table 7), it was found that the concentrations of 14 elements (Na, Al, Fe, Cr, Mn, Ni, Cu, Zn, Se, As, Mo, Cd, Ba and Pb) were all within the limit standards. Theoretically, this drinking water can be consumed by residents as a safe product [

32,

33]. The element concentrations of drinking water indicated by different letters in

Table 7 showed significant differences between the two SUD villages (

p < 0.05). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) revealed that there were significant differences in Ca, K, Mg, Na, Al, Fe, Sr, Li, V, Mn, Ni, Cu, Zn, As, Se, Rb, Mo, Cs, Ba and U among the two SUD villages in drinking water, while there were no significant differences in other elements among the SUD villages (

p < 0.05). Among these two SUD villages, the concentration differences in Zn and Mo were the greatest, with the maximum differences being 25.90 times and 25.46 times, respectively. These were followed by Sr, U, V, Cs, Ca, Fe, Mg, K, Ni and Ba, with maximum differences of 5.46, 3.62, 3.54, 3.30, 3.05, 2.71, 2.50, 2.36, 2.10 and 2.06 times, respectively. Then there were Na, Rb, Cu, Li, As, Mn, Cd, Co, Ga, Cr, P and Pb, with maximum differences of 1.85, 1.73, 1.71, 1.52, 1.44, 1.38, 1.27, 1.22, 1.21, 1.12, 1.11 and 1.10 times, respectively. However, the maximum difference among other elements is within one fold.

By comparing and analyzing the element concentrations in drinking water from four non-SUD villages with the drinking water hygiene standards of China and the WHO (

Figure 4b and

Table 8), it was found that the concentrations of Zn in Lishigeng village was exceeded the limit standards, while the concentrations of 14 elements (Na, Al, Fe, Cr, Mn, Ni, Cu, Zn, Se, As, Mo, Cd, Ba and Pb) in the other three non-SUD village were all within the limit standards [

32,

33]. Therefore, the drinking water in Songping village, Gexi village, and Zejiu village can theoretically be safely consumed by residents. The element concentrations of drinking water indicated by different letters in

Table 8 showed significant differences among the four non-SUD villages (

p < 0.05). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) revealed that there were significant differences in Cd, Ba and U among the four non-SUD villages in drinking water, while other elements exhibited significant differences between the non-SUD villages and non-SUD villages among the four villages (

p < 0.05). Among these four non-SUD villages, the average concentration differences in Zn, U and Mo were the greatest, with the maximum differences being 319.67 times, 198.52 times and 172.56 times, respectively. These were followed by Pb, Li, Mn and Fe, with maximum differences of 30.47, 29.83, 25.43 and 22.20 times, respectively. Then there were Sr, Cd, Ca, Ga and Cu, with maximum differences of 17.17, 15.07, 13.86, 13.56 and 11.08 times, respectively. However, the maximum difference among other elements is within ten folds.

The

t-test results of the average concentrations of drinking water elements in non-SUD and SUD villages in the SUD areas of Yunnan Province are listed in

Table S7. It can be seen from

Table S7 that there are significant differences in Ca, Mg, Mn, Ni, Cu, Ga, As, Cs, Ba, Pb and U in the drinking water between SUD villages and non-SUD villages (

p < 0.05). In addition, the comparison results of drinking water element concentrations between the four non-SUD villages and the SUD villages in the SUD area of Yunnan Province are presented in

Figure 4c. The research found that the concentrations of Fe, Li, Mn, Cu, Cs and Pb in the SUD villages were all lower than those in the non-SUD villages, while the concentrations of Ca, Mg, Na, Sr, V, Ni, Ga, As, Mo and U in the SUD villages were all higher than those in the non-SUD villages. In addition, the concentrations of Fe, Li, Mn, Co, Cu, Zn, Cd, Cs, Ba and Pb in Lishigeng village were higher than those in A’jiju village; the concentrations of K, P, Al, Fe, Li, Cr, Mn, Cu, Rb, Cs and Pb in Songping village were higher than those in Cangdi village. The concentrations of Zn and Cs in Lishigeng village and A’jiju village differ by 223.49 times and 3.21 times, respectively, while the differences in other concentrations are all less than 3 times. The concentrations of Pb, Rb and Cu in Songping village and Cangdi village differ by 7.44 times, 3.63 times and 3.09 times, respectively, and the differences in other element concentrations are all less than 3 times. Therefore, there was a deficiency of Se in drinking water in both the SUD and non-SUD villages in the SUD area of Yunnan Province. However, the drinking water in the SUD villages is more deficient in Fe, Li, Mn, Cu, Cs, and Pb compared to that in the non-SUD villages. Fe is a necessary nutrient for the human body and plays crucial biological functions, including blood production, oxygen transportation, energy metabolism, and immune processes [

34]. Li promotes the development of the animal nervous system [

35]. Mn is an essential trace component in human brain development, intracellular homeostasis, and the functions of various enzymes. Insufficient Mn intake can cause a series of health problems, including overall growth retardation, birth defects, decreased fertility, skeletal dysplasia, and disorders in lipid, protein, and carbohydrate metabolism [

36,

37]. Cu is a vital trace element for various physiological processes in the human body. Cu deficiency can lead to anemia, weakened immune function, delayed growth and development (especially in children), osteoporosis, abnormal cholesterol metabolism, and neurological disorders [

38]. Since Cs and Pb are generally studied as harmful elements, their low concentrations in drinking water are beneficial to humans [

39,

40]. In addition, the concentrations of Fe, Li, Mn, and Cu in the drinking water of the SUD village are also lower than those in some longevity regions (such as Yangdong County in Guangdong, Jinxiang County in Shandong, and Jiangjin District in Chongqing) [

31,

41,

42]. Therefore, the deficiency of Fe, Li, Mn and Cu in village drinking water may pose additional risks to human health.

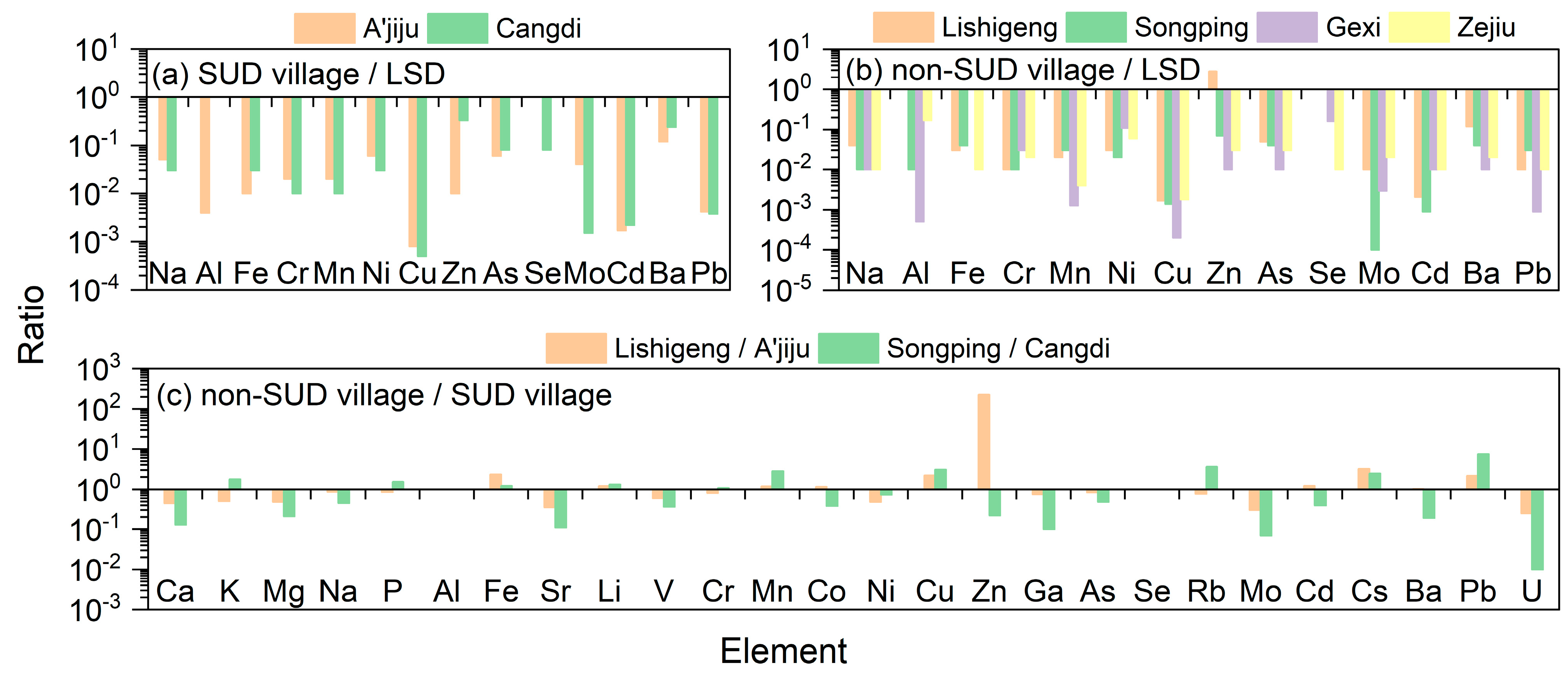

3.4. Comparison of Element Content Between the Diseased Villages of SUD in Yunnan Province and KD in Shaanxi Province

The results of the

t-test for the average concentrations of soil elements in the KD village of Shaanxi Province and the SUD village of Yunnan Province are listed in

Table S8. As show in

Table S8, there are significant differences (

p < 0.05) in the soil elements of Al, K, Na, Se, Ba, Cu, Sr, V, Ga, Mo and Pb between the KD village and SUD village. In addition, the comparison results of the average concentrations of soil elements between the KD village in Shaanxi Province and the SUD village in Yunnan Province are listed in

Figure 5a. The average concentrations of Al, K, Na, Mn, Ba, Li, Sr and Ga in the soil of the KD village are greater than those in the SUD village. Among them, the Na in the soil of the KD village is 6.47 times that of the SUD village, followed by Ba in the soil of the KD village, which is 2.27 times that of the SUD village, while Al, K, Mn, Li, Sr and Ga in the soil of the KD village are 1–2 times those of the SUD village. The average concentrations of Ca, Fe, Mg, Se, As, Cr, Cu, Ni, V, Zn, Co, Mo, Cd, Cs, Pb and U in the soil of the SUD villages of Yunnan Province were all higher than those in the KD villages of Shaanxi Province. Among them, the Se in the SUD villages in Yunnan Province was 21.90 times that of the KD villages in Shaanxi Province, followed by Cd, Pb and Cu in the soil of the SUD village, which were 11.00, 8.56 and 6.56 times higher than those in the KD villages of Shaanxi Province, respectively. Then As and Zn in the soil of the SUD village, which were 4.29 and 4.18 times higher than those in the KD villages of Shaanxi Province, respectively, while the Ca, Fe, Mg, Cr, Ni, V, Co, Mo, Cs and U in the SUD villages of Yunnan Province were 1–2 times higher than those in the KD villages of Shaanxi Province.

The results of the

t-test for the average concentrations of corn elements in the KD village of Shaanxi Province and the SUD village of Yunnan Province are listed in

Table S9. As shown in

Table S9, there are significant differences (

p < 0.05) in the corn elements of Ca, K, Mg, Na, P, Al, Cr, Cu, Mn, Zn, Co, Se, As, V, Ga, Mo and Pb between the KD village and SUD village. In addition, the comparison results of the average concentrations of corn elements between the KD village in Shaanxi Province and the SUD village in Yunnan Province are listed in

Figure 5b. The average concentrations of Ba, Fe, Co, As, Li, Ga, Cd, Pb and U in the corn of the KD village are greater than those in the SUD village. Among them, the Ga in the corn of the KD village is 29.22 times that of the SUD village, followed by As in the corn of the KD village, which is 7.01 times that of the SUD village, while Ba, Fe, Co, Li, Cd, Pb and U in the corn of the KD village were 1–2 times those of the SUD village. The average concentrations of Ca, K, Mg, Na, P, Al, Cr, Cu, Mn, Sr, Zn, Se, V, Ni, Rb, Mo and Cs in the corn of the SUD villages of Yunnan Province were all higher than those in the KD villages of Shaanxi Province. Among them, the V in the SUD villages in Yunnan Province was 136.89 times that of the KD villages in Shaanxi Province, followed by Se, Mo, Cs, Mg and Rb in the corn of the SUD village, which were 5.61, 3.13, 2.44, 2.37 and 2.21 times higher than those in the KD villages of Shaanxi Province, respectively, while the Ca, K, Na, P, Al, Cr, Cu, Mn, Sr, Zn and Ni in the SUD villages of Yunnan Province were 1–2 times higher than those in the KD villages of Shaanxi Province.

The results of the

t-test for the average element concentrations of drinking water in the KD village of Shaanxi Province and the SUD village of Yunnan Province are listed in

Table S10. As shown in

Table S10, there are significant differences (

p < 0.05) in the drinking water elements of K, Na, P, Li, V, Co, Cu, Ga, As, Rb, Cs, Pb and U between the KD village and SUD village. In addition, the comparison results of the average concentrations of drinking water elements between the KD village in Shaanxi Province and the SUD village in Yunnan Province are listed in

Figure 5c. The average concentrations of K, Mg, Na, Li, V, Mn, Co, Cu, Ga, As, Rb, Mo, Cs, Ba and U in the drinking water of the KD village are greater than those in the SUD village. Among them, the Ga in the drinking water of the KD village is 774.82 times that of the SUD village, followed by Rb, Cs, Li and V in the drinking water of the KD village, which is 13.40, 11.05, 5.95 and 5.22 times that of the SUD village, respectively. Then U, Na, Co, Mo, As and K in the drinking water of the SUD village, which were 4.40, 3.78, 3.46, 3.00, 2.66 and 2.56 times higher than those in the KD villages of Shaanxi Province, respectively, while Mg, Mn, Cu and Ba in the drinking water of the KD village were 1–2 times those of the SUD village. The average concentrations of Ca, P, Al, Fe, Sr, Cr, Ni, Zn, Se, Cd and Pb in the drinking water of the SUD villages of Yunnan Province were all higher than those in the KD villages of Shaanxi Province. Among them, the Se, Zn, P and Pb in the SUD villages in Yunnan Province was 62.05, 18.23, 8.57 and 5.06 times that of the KD villages in Shaanxi Province, respectively, followed by Cd, Fe and Sr in the drinking water of the SUD village, which were 3.08, 2.91 and 2.42 times higher than those in the KD villages of Shaanxi Province, respectively, while the Ca, Cr and Ni in the SUD villages of Yunnan Province were 1–2 times higher than those in the KD villages of Shaanxi Province.

To sum up, the average concentrations of Ca, Cr, Ni, Zn and Se in the soil, corn and drinking water of the SUD villages in Yunnan Province were all higher than those of the KD villages in Shaanxi Province. The concentrations of Ca, P, Al, Sr, Cr, Ni, Zn and Se in corn and drinking water, which are directly related to the residents’ diet, were higher in the SUD villages of Yunnan Province than in the KD villages of Shaanxi Province. The average concentrations of Ba, Li and Ga in the soil, corn and drinking water of the KD village in Shaanxi Province were all higher than those in the SUD village of Yunnan Province. The concentrations of Ba, Co, As, Li, Ga and U in corn and drinking water, which are directly related to the residents’ diet, were higher in the KD village of Shaanxi Province than in the SUD village of Yunnan Province. This indicates that the trace elements in the environmental medium of the KD Village in Shaanxi Province are more deficient than those in the SUD village of Yunnan Province, especially in corn and drinking water related to human life.

3.5. Health Risk Assessment of Residents in the SUD Village and Non-SUD Village of Yunnan Province

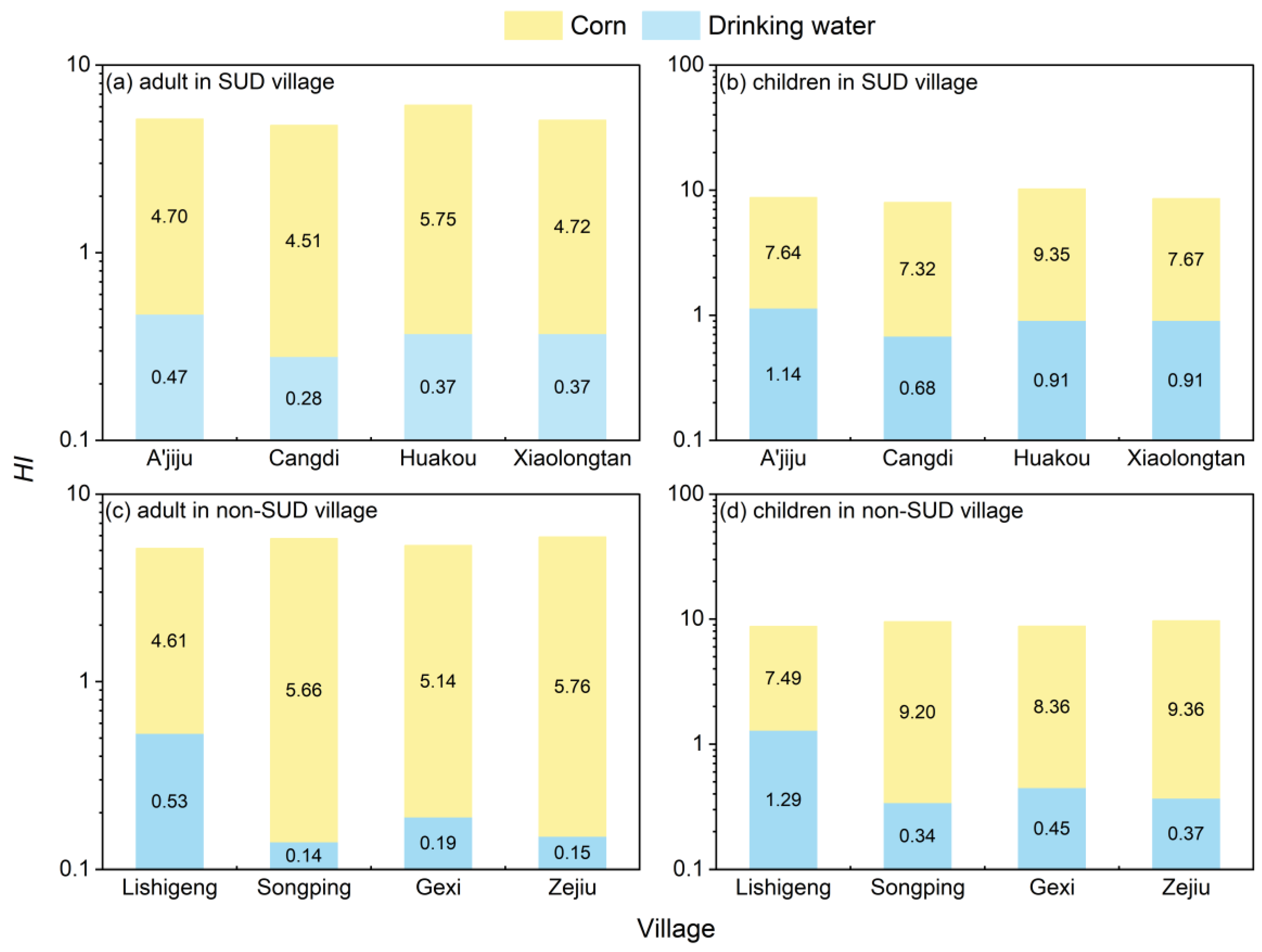

The HI results for adults and children in the SUD villages of Yunnan Province through the ingestion of corn and drinking water are presented in

Figure 6a and

Figure 6b, respectively. The average HI for 17 trace elements in corn and drinking water consumed by adults in the four SUD villages was 5.29 (4.78–6.12), and for children it was 8.90 (8.00–10.26), both higher than the acceptable non-carcinogenic risk level of 1. Additionally, it was found in all four SUD villages that the non-carcinogenic risk for children was higher than that for adults. The non-carcinogenic risk for adults and children through the consumption of corn in the villages of A’jiju village, Cangdi village, Huakou village and Xiaolongtan village was higher than that through drinking water, and the contribution to the total hazard index was over 90% (for adults) and 87% (for children). Regarding the ingestion of the 17 trace elements via corn, Cr and Mn were the elements with the highest HQ values for both adults and children (

Tables S11 and S12). The average HQ values for Cr and Mn in adults were 1.45 (1.12–1.95) and 1.17 (1.04–1.52), respectively, and for children they were 2.36 (1.82–2.31) and 1.91 (1.69–2.48), both higher than the acceptable non-carcinogenic risk level of 1, and contributing over 24.88% and 18.11%, respectively, to the total HQ. Regarding the ingestion of the 17 trace elements via drinking water, the HI and HQ of the 17 trace elements in drinking water for adults in the villages of A’jiju and Cangdi were both below 1, theoretically having no non-carcinogenic risk, and contributed over 77% to the total HQ. Since drinking water was not collected in Huakou village and Xiaolongtan village for health risk calculation, the drinking water concentration used for health risk calculation was replaced by the average value of drinking water from the other two villages. Therefore, these two villages were not discussed in this context. In summary, Cr and Mn in corn are the main non-carcinogenic risk factors in the SUD area of Yunnan Province.

Similarly, the HI results for adults and children in the non-SUD villages of Yunnan Province through the ingestion of corn and drinking water are presented in

Figure 6c and

Figure 6d, respectively. The average HI for 17 trace elements in corn and drinking water consumed by adults in the four non-SUD villages was 5.55 (5.14–5.91), and for children it was 9.22 (8.79–9.73), both also higher than the acceptable non-carcinogenic risk level of 1. Additionally, it was found in all four non-SUD villages that the non-carcinogenic risk for children was higher than that for adults. The non-carcinogenic risk for adults and children through the consumption of corn in the non-SUD villages was higher than that through drinking water, and the contribution to the total hazard index was over 89% (for adults) and 85% (for children). Regarding the ingestion of the 17 trace elements via corn (

Table S13), Cr and Mn were the elements with the highest HQ values for both adults and children in Lishigeng village and Songping village. The average HQ values for Cr and Mn in adults from these two non-SUD villages were 1.37 and 1.33, respectively, while for children, they were 2.22 and 2.17, all exceeding the acceptable non-carcinogenic risk level of 1. The proportions all exceeded 23.00% and 22.00%, respectively. In Gexi village and Zejiu village, Cr and Mo were the elements with the highest HQ values for both adults and children, respectively. The average HQ values for Cr and Mo in adults from these two non-disease villages were 1.13 and 0.96, respectively, while for children, they were 1.84 and 1.56. These values also exceeded the acceptable non-carcinogenic risk level of 1, with the proportions exceeding this level surpassing 19.00% and 17.00%, respectively. Therefore, Cr, Mn and Mo in corn from non-SUD villages are the main non-carcinogenic risk factors. For adults, the HQ and HI values of 17 trace elements in drinking water are all below 1 (

Table S14), and theoretically, there is no non-carcinogenic risk.

In conclusion, the non-carcinogenic risks for children in both the SUD villages and the non-SUD villages are higher than those for adults. This is mainly because children are more vulnerable to the threat of trace element pollution than adults [

43]. The trace elements entering the human body through corn are more than those through drinking water, as the intake of crops is the main way for the human body to absorb trace elements [

44]. In the SUD villages and non-SUD villages of Yunnan Province, the Cr and Mn in corn are the most significant non-carcinogenic risk factors, but the non-carcinogenic contribution of Mo in corn in the non-SUD villages (Gexi village and Zejiu village) is greater than that of Mn. The difference is that the non-carcinogenic risk contribution of consuming corn through corn for adults and children in non-SUD villages is much higher than that through drinking water. Moreover, all the drinking water in the SUD area has no non-carcinogenic risk and can be safely consumed.