Abstract

Background: The Port of Santa Marta, located on Colombia’s northern Caribbean coast, plays a vital role in the country’s maritime trade, particularly in the export of agricultural and perishable goods. This raises the question: how competitive is Santa Marta’s container terminal compared to national and regional ports, and what strategic factors shape its performance within the Colombia and Latin American maritime logistics system? Methods: This study evaluates the port’s competitiveness by applying Porter’s Extended Diamond Model. A mixed-methods ap-proach was employed, combining structured surveys and interviews with port stakeholders and operational data analysis. A competitiveness matrix was developed and examined using standardized residuals and L1 regression to identify critical performance gaps and strengths. Results: The analysis reveals several competitive advantages, including the port’s strategic location, natural deep-water access, and advanced infrastructure for refrigerated cargo. It also benefits from skilled labour and proximity to global shipping routes, such as the Panama Canal. Nonetheless, challenges remain in storage capacity, limited road connectivity, and insufficient public investment in hinterland infrastructure. Conclusions: While the Port of Santa Marta shows strong maritime capabilities and spe-cialized services, addressing its land-side and institutional constraints is essential for positioning it as a resilient, competitive logistics hub in the Latin American and Caribbean region.

1. Introduction

Ports are no longer passive access points, but strategic nodes in global value chains. However, mid-sized terminals in Latin America remain underrepresented in empirical research on competitiveness, creating a blind spot in public policy, namely, decisions on capacity expansion, modal integration, or digital investment are often made without evidence tailored to their scale and context. The Port of Santa Marta epitomizes this gap. Despite handling nearly half of Colombia’s coal exports and a growing share of agri-food containers, it ranks fourth nationally in container volume and lacks systematic comparative assessments of its competitive advantages and bottlenecks.

This study therefore asks the following: What factors most influence the competitiveness of Santa Marta’s container sector vis-à-vis its Caribbean peers, and where should limited resources be prioritized? We respond by integrating the Extended Diamond Model of Porter (adapted to port logistics) with a robust L1 regression of a 70-cell perception matrix constructed from 30 surveys and expert interviews. This approach combines a qualitative perspective with quantitative rigor and offers both academic innovation (the first application of the method in a Colombian port) and practical metrics for public policymakers addressing congestion, modal imbalance, and logistics-driven investment decisions.

This study examines stakeholder perceptions of container traffic at the Port of Santa Marta, with an emphasis on key competitiveness factors to better understand the port’s current position. The findings aim to inform policymakers by identifying both perception-based disparities and the most influential variables shaping competitiveness in the container sector.

The Port of Santa Marta, located on the northern coast of Colombia, has long been a key hub for maritime trade, particularly in exporting agricultural produce. Its strategic proximity to the Panama Canal, access to transoceanic routes, and natural deep-water harbors offer significant advantages in terms of accessibility and cost efficiency. Historically, Santa Marta was a primary settlement for the Spanish in the 16th and 17th centuries, but trade shifted to other areas as settlers moved inland in search of minerals. By the 18th and 19th centuries, Santa Marta had become more focused on imports. In the 20th century, the port’s development was driven by population growth and the construction of a railroad by the United Fruit Company [1], connecting banana plantations to the port. Today, the Port of Santa Marta functions as a multipurpose facility, handling a variety of cargo types, including containers, solid bulk (notably coal), liquid bulk (such as palm oil), and general cargo [2]. It is also recognized for its advanced infrastructure and capacity to manage refrigerated cargo, which is vital for exporting perishable goods to markets such as the U.S. and Europe.

The regulatory environment transformed with Law 01 of 1991 [3], which redefined the state’s role in port management, leading to the establishment of regional port societies with majority private sector [4] participation by 1993. This legal framework contributed to a marked improvement in the port business in Colombia and across Latin America and the Caribbean [5], rising from 52% to 64% between 1999 and 2009, driven by private port operations [6,7].

Overview of Santa Marta’s Maritime Traffic

Santa Marta currently ranks second within the Colombian port system after Buenaventura in total tonnage handled. However, it ranks fourth in Colombia for container traffic. Notably, more than 50% of the coal exported from Colombia passes through the Port of Santa Marta, along with a significant portion of liquid bulk cargo, primarily palm oil [2] (Table 1). When considering Twenty-Foot Equivalent Unit (TEU) traffic, it is important to highlight that both Santa Marta and the entire Colombian port system are relatively small compared to other Latin American and Caribbean (LAC) countries, as well as on a global scale. Colombia accounts for only a small fraction of global container traffic. Cartagena, however, stands out as one of the main container handling hubs in the LAC region (Table 2).

Table 1.

Tonnage handled by the most important port societies in Colombia and type of cargo—2022.

Table 2.

Percentage comparison of TEU movements of Santa Marta’s ports relative to other movements for the year 2023.

Santa Marta has traditionally been an understudied port, primarily due to limited data on its container movements and its role within a relatively small port system. However, its physical and logistical characteristics, proximity to two major ports in the Colombian Caribbean, and its potential for tourism [8] development make it an intriguing subject for study, especially in terms of efficiency and competitiveness.

In the context of globalization and the increase in international trade, port efficiency and competitiveness have become crucial factors for regional and national economic development [9]. The competitiveness of a port is evaluated across multiple dimensions, including infrastructure, accessibility, technology, services, and the ability to adapt to market demands [10]. In this regard, the container terminal at the Port of Santa Marta faces unique challenges and opportunities that require a thorough and rigorous analysis to identify its strengths and areas for improvement.

2. Literature Review

The literature search was conducted across three major academic databases, namely, Scopus, Web of Science, and ScienceDirect. The search strategy employed combinations of keywords such as “port competitiveness” and “sustainability”, “smart port” and “digital transformation”, and “green logistics” and “governance”. The inclusion criteria were as follows: publications issued between 2010 and 2024, peer-reviewed journal articles, studies published in English or Spanish, and empirical or conceptual research specifically focused on maritime ports. Dry ports and airport-related studies were excluded. The exclusion criteria comprised conference proceedings, editorial reviews, non-academic or outreach documents, and studies not directly addressing seaports or terminal operations.

Several factors have been considered synonymous with competitive success in the port context. In the 1990s, physical conditions such as geographic location and maritime access were emphasized [11]. In the 2000s, productivity in the use of logistical resources became a focus, followed by the capacity to compete from a demand perspective [12,13]. Competitiveness has been studied from the efficiency perspective [14], considering input resources and output performance, typically measured in TEU traffic or the tonnage of goods moved. However, for the purposes of this document, competitiveness is defined as the degree to which a port competes with other ports, considering all aspects of its technical and logistical operations [15].

To review the studies on port competitiveness, various methodologies and criteria have been considered in this research [16]. The methodologies and criteria detailed in the next table highlight a multifaceted approach to evaluating port efficiency and competitiveness. By employing diverse methods such as economic modeling [12], case studies, and simulation models, researchers can obtain a comprehensive understanding of the factors that influence port operations. The geographical focus of these studies underscores the global relevance and regional specificities of port competitiveness research [17]. This comprehensive approach allows for a nuanced analysis of port performance across different contexts and operational conditions.

When analyzing the key articles related to a literature review on port competitiveness (which, it should be noted, is not very extensive in the terms studied in this research), we identified the following references [15,18,19,20,21,22,23]. From these, the main methodologies applied, criteria, data used, and the most studied ports or regions around the world were extracted and are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Methodologies and criteria most used for the analysis of port competitiveness in recent years.

In the field of competitiveness, most research has been published since 2010, focusing primarily on competition and efficiency studies using multi-criteria analysis methods [20]. Most of these studies have been conducted in Asia and Europe, with limited literature available in the Americas, particularly in Colombia [24], which is the context of this study. The primary objective and innovative aspect of this research is the application of a technical–economic model to study the container terminal of Santa Marta and its port environment by measuring the perceptions (through surveys and interviews) of port operators involved in container traffic operations. The Extended Diamond Model of Porter, adapted to include specific port environment factors, will be employed as the economic model [11] in conjunction with advanced statistical models and linear programming to identify the most representative variables affecting the competitiveness of the Port of Santa Marta [12].

The Extended Diamond Model of Porter provides a robust theoretical framework [25] for evaluating the competitiveness of the container terminal at the Port of Santa Marta. This model examines five main determinants of competitive advantage, as follows: factor conditions, demand conditions, related and supporting industries, firm strategy, structure and rivalry [11], and the role of government policies. In this context, the container terminal at the Port of Santa Marta, strategically located on the northern coast of Colombia, emerges as a focal point of study due to its potential utility (and related challenges) in the national and international supply chain. Despite its natural advantages, it faces fierce competition from other regional ports, such as Cartagena and Barranquilla. Therefore, evaluating its competitiveness is crucial to identifying its strengths and areas for improvement and formulating strategies to enhance its position in the global market [26].

In summary, the objective of this study is to identify the key factors influencing port competitiveness for container traffic at the Port of Santa Marta in comparison with its main competitors, the Colombian ports of Cartagena and Barranquilla. The Extended Diamond Model of Porter was used in combination with L1 regression, which provides statistical robustness and allows for credible comparisons between variables. This applied technical–economic analysis presents a competitiveness matrix based on interviews and surveys with key stakeholders in the sector, highlighting perceptions with standardized data. It provides a perspective related to the actual operation of the port.

In addition to a well-structured diagnosis, clear competitive advantages (maritime accessibility, trained personnel) and weaknesses (road infrastructure, rail cooperation) are identified. This facilitates the development of proposals for the port.

This document is structured in six main sections. Section 1 provides an introduction. Section 2 offers a review of the literature and an overview of the main background and context of this research. Section 3 describes the materials, data collection, and methods. Section 4 shows the analysis and procedures used in this study. Section 5 presents the results, as well as the findings and a discussion thereof. Finally, Section 6 describes the conclusions derived from the results.

3. Materials and Methods

In this section, specific data, including port operational criteria and annual performance metrics, will be meticulously detailed. Furthermore, the step-by-step methodologies utilized for this analysis will be comprehensively explained, including the measurement of perceptions through surveys and interviews with port operators involved in container traffic operations. According to the primary objective of this research, the innovative aspect lies in the application of a technical–economic model to examine the competitive factors of the container terminal of Santa Marta.

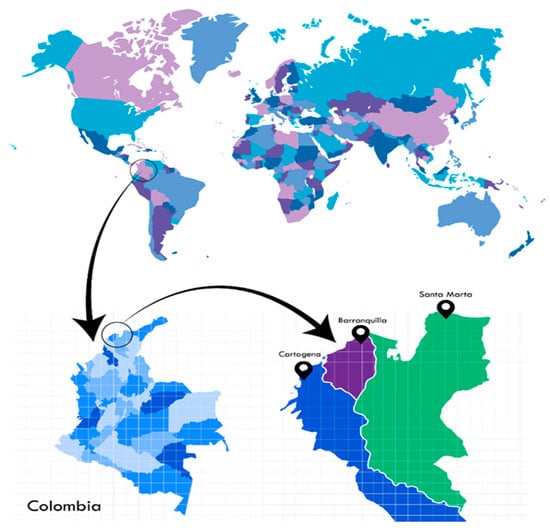

Santa Marta has been chosen as the focus of this study due to its interesting logistical characteristics (which can be largely exploited) compared to Barranquilla and Cartagena, since these ports are part of the most important port sector in Colombia within a 200 km radius. Its proximity to the Panama Canal and key trade routes to the Caribbean, the eastern United States, and Europe further enhances its strategic value. Additionally, the ease of the road and rail transportation of export cargo from these three Caribbean ports presents a significant advantage over the Pacific port of Buenaventura. Likewise, the Chocó port has been removed from this study, given its characteristics and particularities that have nothing to do with the Caribbean.

The Port of Santa Marta was selected not only because of the researchers’ specific interests, but also due to the limited scope of existing studies on its economic potential and port activities. Its unique geographic and infrastructural features, such as its natural deep-water harbor and strategic location near major trade routes, provide notable competitive advantages that merit detailed examination. In the context of growing global trade complexity, a thorough analysis of the Port of Santa Marta ‘s container traffic and competitiveness can offer crucial insights for stakeholders, helping optimize resource allocation, guide policy decisions, and strengthen its market position. Without this focused research, there is a risk that Santa Marta’s potential may go unrealized, hindering its ability to effectively compete in an ever-changing maritime environment.

Container traffic was chosen as the focus of this study due to its dynamic nature and the potential for the Port of Santa Marta to diversify into other significant traffic types, such as coal and palm oil [2]. While coal and palm oil are strategically important for ports such as Santa Marta, their less flexible characteristics and the need for more specialized infrastructure make them less suitable as general indicators of port competitiveness compared to container traffic [27]. Containers, as a standardized and modular transport unit, allow for greater cargo diversification, enhancing the port’s ability to adapt to different types of trade and increasing its competitiveness in the dynamic environment of international commerce.

Data Description

All the selected ports are located on the northern coast of Colombia, in what is called the Colombian Caribbean, and we take the Port of Santa Marta as the focus of this study [28]. The data presented in this research come from two main sources. The logistical and technical criteria were obtained from the annual official bulletins of the General Superintendence of Port and Transport of Colombia, which provide a general overview of the Colombian port system. These data have been used to understand the landscape of the three main Caribbean ports and their key characteristics, allowing for an objective comparison between them.

The data used to generate the economic competitiveness study matrix based on the Extended Diamond Model of Porter [11], and consequently to establish the main competitiveness variables of the Santa Marta container terminal, were obtained from interviews and surveys conducted between November 2023 and March 2024 with port operators involved in container traffic operations. The interviews and surveys were voluntarily completed by the participants and are protected under Law 1581 of 2012 in the Republic of Colombia.

The companies that participated in this academic exercise, including in interviews and surveys, are detailed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Port operators involved in container traffic operations.

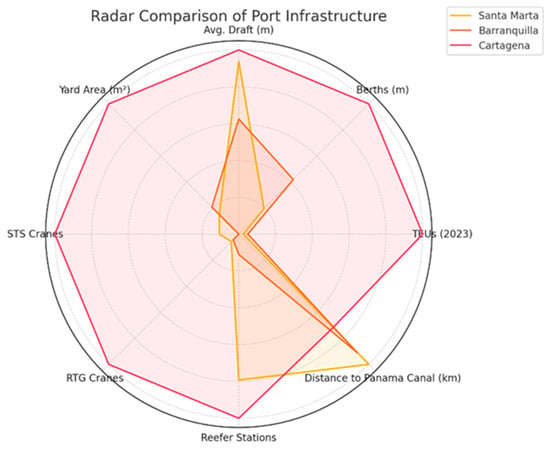

Regarding the operational characteristics of the container terminals in the Colombian Caribbean, as detailed in Table 5 and Table 6, there are significant differences among them. Cartagena serves as a major transshipment logistics hub (Figure 1), ranking fifth in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), and it operates two terminals for container traffic [29]. In contrast, Barranquilla and Santa Marta are multipurpose ports with very low container traffic, being constrained by physical space and available machinery, compared to Cartagena [30]. However, these ports are more efficient in terms of bulk cargo operations, with Santa Marta ranking second after Buenaventura in terms of coal traffic.

Table 5.

Operational and logistic criteria data.

Table 6.

Throughput (TEUs/year) in recent years by port.

Figure 1.

Radar chart comparing key infrastructure attributes of Santa Marta, Barranquilla, and Cartagena ports in Colombia and the TEUs resulting from port handling operations.

Cartagena’s role as a transshipment hub is underscored by its extensive infrastructure and capacity to handle large volumes of containerized cargo, making it a critical node in the global supply chain. The port’s strategic location and advanced facilities enable it to accommodate large vessels and seamless transshipment operations, thus contributing to its prominent position in the LAC region [27].

On the other hand, Barranquilla and Santa Marta play a vital role in bulk cargo operations but are limited in their container handling capabilities. These ports are equipped to manage significant volumes of bulk commodities, with Santa Marta in particular excelling in coal exports. The port’s efficiency in handling bulk cargo is a key factor in its ranking as the second largest coal port in Colombia, following Buenaventura. Additionally, the port’s strategic location and well-developed infrastructure make it an attractive option for other types of cargo such as agricultural products and manufactured goods, contributing to its overall importance in the country’s economy.

These operational distinctions highlight the diverse roles and capabilities of Colombian Caribbean ports, each contributing uniquely to the regional and global logistics landscape [31]. The differences in infrastructure, capacity, and specialization underscore the importance of tailored strategies to enhance competitiveness and operational efficiency across the various types of cargo handled by these ports.

Regarding natural conditions, Santa Marta ranks first. It does not require dredging because it is a deep-water port with an access channel that exceeds 18 m in depth. Barranquilla, however, faces significant limitations regarding its access and draft, given that it is located 25 km from the mouth of the Magdalena River. The sedimentation dynamics in the final part of the river necessitate constant dredging, which increases associated costs and freight charges. Cartagena is constrained by space as it is situated in the enclave of Manga Island within the city of Cartagena, and cannot physically expand further [30]. Santa Marta also faces a similar issue at present. Therefore, studying the efficiency and competitiveness of these ports is of the utmost priority.

It is essential to highlight that Santa Marta’s advantageous natural conditions, including its deep-water port, place it at the forefront compared with other ports in the region. The ongoing need for dredging in Barranquilla because of its location along the sediment-heavy Magdalena River imposes higher operational costs and logistical challenges. Cartagena’s spatial constraints within Manga Island limit its potential for expansion, similar to the spatial limitations faced by the Port of Santa Marta.

Given these factors, a thorough examination of these ports’ efficiency and competitiveness is crucial. By understanding the unique challenges and advantages of each port, strategies can be developed to enhance its operational efficiency and competitive standing in the global market. This analysis is particularly pertinent considering the increasing competition in port markets worldwide [7], driven by the rapid development of international containers and intermodal transport. Therefore, a detailed study of these ports will provide valuable insights into improving their competitiveness and positioning in the international trade network.

In the geographical context, Santa Marta, Barranquilla, and Cartagena are strategically positioned near the Panama Canal (Figure 2), which is a key route for international trade. They occupy an intermediary location between Southeast Asian and European markets, as well as major production and consumption centers such as Brazil and the United States. These competitive advantages have been a focal point of discussion among Colombian local experts, especially considering that competitiveness in port markets worldwide has significantly increased. Regions once viewed as monopolistic are now experiencing intense competition due to the rapid development of international containers and intermodal transport, transforming formerly monopolistic markets into areas of fierce rivalry [32].

Figure 2.

Geographic context of the ports mentioned. From east to west, Santa Marta, Barranquilla, and Cartagena.

Table 7 illustrates that Santa Marta is a pivotal port for Colombia’s agricultural exports, notably bananas and coffee, which are key commodities. The port’s infrastructure supports substantial volumes of bulk cargo such as coal and palm oil, contributing to its versatility. Its strategic location on the Caribbean coast facilitates efficient connections to North America and Europe. However, the annual vessel calls at Santa Marta are fewer compared to Cartagena, which limits its overall cargo throughput and transshipment capacity. Barranquilla functions as an industrial hub, managing a diverse array of goods, including steel products, machinery, and chemicals. This port plays a significant role in bolstering Colombia’s manufacturing and industrial sectors. With slightly more vessel calls than Santa Marta, Barranquilla is well equipped to handle significant cargo volumes, thereby enhancing its competitive edge. Nevertheless, it lacks the extensive transshipment facilities available in Cartagena.

Table 7.

Analysis of North Colombian container terminals.

Cartagena emerges as the most competitive and efficient port among the three, accommodating the highest number of annual vessel calls. It services a wider range of shipping lines and destinations, including key routes to Asia, thereby enhancing its role as a major transshipment hub in the region. Cartagena’s capacity to handle a wide variety of cargo, including high-value perishables such as flowers and coffee, consumer goods, and coal, underscores its versatility and strategic importance. The port’s extensive infrastructure, comprising advanced container handling facilities and numerous quay and yard cranes, positions it as a leader in port efficiency and competitiveness both regionally and globally.

4. Methodology

Given that the primary objective and innovative aspect of this research is the application of a techno-economic model to analyze the Santa Marta container terminal and its port environment, this study measures the perceptions of operators involved in container traffic operations through surveys and interviews. The following section outlines the methodology used, including the approach to data collection and the system of equations employed in the analysis.

After identifying the various entities, institutions, and companies engaged in the containerization process, a representative sample was selected. The selection of companies and institutions to be surveyed was not random but rather intentional, based on the specific importance of each company or institution to port activities. This importance was assessed based on the number of employees, the area of activity within the Port of Santa Marta, and the goal of covering all activities related to port operations for container movement. We assessed the local port authority, maritime and customs agencies, freight forwarders, container terminals, cargo agents, logistics operators (stevedores and mooring personnel), and land transport operators. Specifically, 30 local experts were selected, representing approximately 80% of the total institutions and companies directly involved in container traffic and over 90% of employment in the sector.

All companies were surveyed using a structured questionnaire divided into three parts. The first part of the questionnaire included questions on the identification or situation of the company, its number of employees, the sub-sector it belongs to within port activities, and its specific area of operation. The second part of the survey is the most important and is based on a competitiveness matrix. The groups of questions in this section were divided according to the Extended Diamond Model of Porter, focusing on factor conditions, demand conditions, supporting industries, port competition, and the role of the public sector at various levels (local and national). Respondents were asked to rate a series of variables on a scale of intensity/importance based on their perception, ranging from +2 to −2. This scale assesses whether the variables constitute a disadvantage or advantage for the port’s competitiveness, where the following pertains: −2 = very unfavorable (variables representing a significant competitive disadvantage for the Port of Santa Marta); −1 = unfavorable; 0 = neutral (variables neither advantageous nor disadvantageous for competitiveness); +1 = favorable; +2 = very favorable (variables representing a significant competitive advantage for the Port of Santa Marta).

The third part of the survey consisted of open-ended questions to derive detailed explanations of the data from the previous section, and to corroborate them qualitatively. The entire survey, including all three parts, was conducted with the director or highest-ranking executive/manager/official of each organization at their headquarters. The duration of the interviews was between one and two hours.

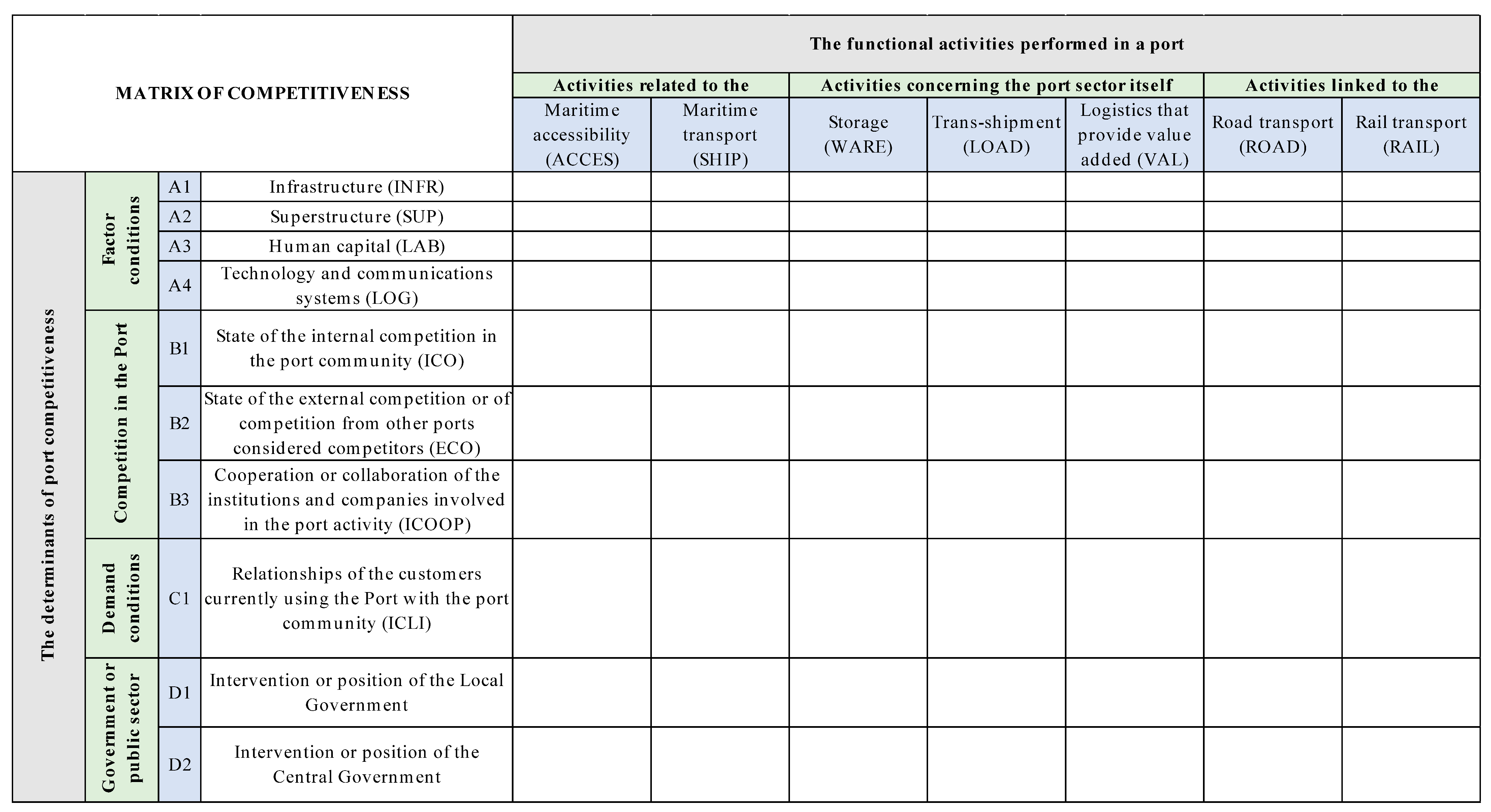

The survey matrix presents the perceptions obtained from the second part of the questionnaire. It combines the functional activities performed in the port, from a perspective of logistic chain, with the determinants of port competitiveness [12] as shown in Appendix A.

Applied Model

Based on the survey results, a matrix X(m) consisting of 10 rows and 7 columns has been constructed for each person ‘m’ from each company or institution interviewed—Appendix A. It is apparent that some respondents may provide answers skewed towards the higher or lower extremities of ratings compared to others. This could stem from differences in the personalities or attitudes of the interviewees rather than actual variations related to the port’s competitiveness. To mitigate these distortions, the responses to each question have been standardized in the following manner:

Here, i = 1, 2, …, 10 and j = 1, 2, …, 7. The 30 matrices Z(m) are summarized into a single matrix Z by taking the average of each cell zij from all matrices ‘m’, as follows:

The standardized matrix Z is displayed in Table 8. The objective is to analyze which rows and columns receive positive or negative assessments and to identify any interactions between specific rows and columns. Unlike other methods, such as the ANOVA (Analysis of Variance) test, the proposed methodology accounts for the influence of outliers. As a result, these anomalous values can affect the outcome instead of being detected. Estimating the model using ordinary least squares is relatively straightforward, but this method is highly sensitive to extreme observations. To mitigate the distortion caused by such influences, a more robust technique called L1 regression is employed [33].

Table 8.

Standardized matrix Z.

The regression model seeks to elucidate the average response across the 70 cells in matrix Z. It utilizes categorical explanatory variables that correspond to the indices of the matrix’s columns and rows. These explanatory variables are typically represented using binary dummy variables. In this case, each categorical variable has 10 and 7 levels, respectively. Therefore, they can be encoded into 9 dummy variables I(k) and 6 dummy variables J(l), respectively. The regression model thus becomes

where for , and for the rest of the possible cases. Likewise, for , and for the rest of the cases. The independent term is and is the random error. The coefficients α(k) and (l) are the main effects of the rows and columns. Using this model, the values of the parameters (1), α(2), …, α(10), β(1), …, β(7) are estimated. With these coefficients, the equation finally obtained corresponds to the following formula:

The estimated values obtained are aggregated into the estimated matrix and are represented in Table 9. The values of the main effects of the rows, , are indicated on the horizontal axis, and the main effects of the columns, , are shown on the vertical axis. The relative positions of these values serve as a measure of the overall assessment of rows and columns.

Table 9.

Estimated matrix Z.

From this point onwards, the residuals are generated based on the differences between the actual values of the standardized response matrix Z and the values estimated by the model,

The model estimation provides as many residuals as there are cells in the competitiveness matrix (70 cells). The analysis of these residuals reveals competitive advantages and disadvantages by considering whether they are outliers as well as their positions within the matrix.

If any of the residuals are unusually large, it can be interpreted that the actual value of the dependent variable is not fully explained by the main effect of the row or column. Therefore, following the criteria used in Europe [12] and South America [34], it can be asserted that there is an interaction between row i and column j, indicating a relationship between the functional activities carried out in the port and the resources required for port operations.

Therefore, the detection of extremely large residuals, both positive and negative, allows for the identification of advantages and disadvantages, respectively, in terms of competitiveness. The best way to detect in which observations the interaction occurs is through the graphical representation of standardized residuals against estimated values . If these residuals are approximately normally distributed, 90% of them will fall within the range (−1.5, +1.5). Values exceeding this range are considered extreme, indicating positive or negative interactions, respectively.

The results of applying this procedure are discussed later. In the analysis, all questionnaires were treated equally, assigning the same weight to all responses. The residuals of the econometric model are presented in Table 10, highlighting both positive and negative extremes. This discussion reveals the competitive advantages and disadvantages of the port under study. Essentially, the residuals were calculated to identify deviations from the expected values, as previously mentioned, revealing insights into the port’s performance.

Table 10.

Matrix of competitiveness with the values of standardized residuals.

The estimated coefficients (also called regression coefficients or parameters) represent the relationship between the independent variables (predictors) and the dependent variable (outcome). These coefficients quantify the magnitude and direction of each predictor variable’s effect on the dependent variable, as shown in Table 11.

Table 11.

Estimations made utilizing the 70 observations.

5. Results and Discussions

This research contributes to the field by applying a techno-economic model to evaluate the competitiveness of the Santa Marta container terminal within its broader port ecosystem. Through a combination of stakeholder surveys, statistical normalization, and L1 regression analysis, this study delivers a robust assessment of key competitive drivers. The methodology allows for the identification of performance gaps and strategic opportunities, offering practical insights that inform decision-making and enhance port efficiency.

The results are presented in a standardized competitiveness matrix (Table 12), based on the data outlined in Table 10. The values are color-coded according to their relative performance: red indicates competitive disadvantages (outliers), blue highlights key strengths, and green marks borderline cases. These findings were also thematically organized according to the four pillars of the conceptual framework developed in this study, as follows: port governance and institutional context; digital transformation and innovation; environmental sustainability and resilience; and operational competitiveness, including connectivity, infrastructure, and logistical performance.

Table 12.

Matrix of competitiveness with the values of standardized residuals.

The methodology used in the analysis of the port competitiveness survey matrix combines functional activities and determinants of port competitiveness. By standardizing responses and employing L1 regression, this study aims to identify significant interactions that reveal competitive advantages and disadvantages, strengths, weaknesses, challenges, and areas to improve.

5.1. Key Findings from Interaction Insights

5.1.1. Port Condition Factor

Infrastructure

- Santa Marta boasts strong maritime infrastructure (INF-ACCES: 2.174), facilitating efficient ship entry and exit. This capability plays a key role in attracting shipping lines and ensuring rapid turnaround times, significantly enhancing the port’s global connectivity. Santa Marta’s natural deep-water harbor is a significant advantage, accommodating large vessels such as post-Panamax ships. However, the port needs to address infrastructural improvements to fully leverage this natural benefit.

- Storage and road transport (INFR–WARE: −2.413, INFR-ROAD: −2.495)—Insufficient storage capacity results in congestion and operational delays. Additionally, inadequate and unsafe road infrastructure hampers the efficient movement of goods, negatively impacting the port’s overall competitiveness.

Superstructure

- Although infrastructure provides a solid foundation, further investment in superstructure, such as the addition of more container cranes, is essential to enhance operational capacity and improve overall port efficiency.

Human capital

- Two important aspects (LAB-ROAD: −5.087) were identified. First, there may be inefficiencies in the management of the labor force involved in road transport, resulting in delays, miscommunication, and bottlenecks in the flow of goods. This could be attributed to inadequate staffing, insufficient training, or a lack of proper oversight in logistical operations. Second, it also suggests that road transport workers may be operating under suboptimal conditions, negatively impacting their performance, safety, and overall efficiency. These conditions may include long working hours, inadequate facilities, or unsafe road infrastructure.

Technology and communications

- The implementation of advanced technologies in storage (WARE) has significantly enhanced inventory management and cargo traceability, improving overall operational efficiency (TEC LOG–WARE: 5.719). Virtual platforms for handling payments and cargo manifests provide a competitive edge. However, response times on these platforms require improvements to maximize their potential.

- The positive impact of infrastructure and technology (INFR–TEC LOG)—Notable positive interactions in infrastructure (INFR) and technology and communication systems (TEC LOG) highlight that investments in these areas have a direct, beneficial impact on the port’s operational performance and competitiveness.

5.1.2. Competition in the Port

- An advantage of road transport over external competition (ECO-ROAD: 2.660) suggests that the Port of Santa Marta benefits from good land connectivity, facilitating the efficient movement of cargo to and from the port. It is particularly advantageous as the closest Caribbean port to major production centers in Colombia. However, there is a lack of adequate road infrastructure, good route conditions, and reliable land transport services, and there is a need to establish logistical agreements to optimize the flow of goods.

- State of internal competition (B1)—A healthy competitive environment within the port community fosters innovation and efficiency.

- State of external competition (B2)—Intense competition from ports such as Barranquilla and Cartagena presents challenges. Cartagena, in particular, exceeds efficiency levels and ranks among top LAC HUB terminals, while Barranquilla faces issues with maritime access and outdated equipment.

- External competition and maritime transport (ECO–SHIP: −2.544)—This reflects the perception that the port faces difficulties in adapting to trends and changes in the global maritime industry, such as digitalization, sustainability, and the increasing competition from other ports. The negative results may indicate a general perception among experts that the Port of Santa Marta is not fully leveraging its competitive advantages or that there are significant areas for improvement in terms of management, operations, or the promotion of its services.

- Road and rail connectivity—Improving road security and optimizing cargo handling operations to the rail system is crucial (ICOOP—RAIL: −4.790). For the Port of Santa Marta, the internal cooperation in terms of rail transport should ideally be characterized by a strategic collaboration between the Port of Santa Marta and the railway companies operating in the region, primarily Fenoco S.A. (acronyms in Spanish for Ferrocarriles del Norte de Colombia, the sole service provider). However, this cooperation is not fully effective and remains essential for optimizing the port’s logistics chain, particularly for transporting bulk cargo, such as coal, from the mines in the interior of the country to the port facilities. Rail transport plays a critical role in reducing transportation costs, improving operational efficiency, and mitigating environmental impact compared to other modes of transport, such as road transport. Through future service agreements, the better coordination of schedules, and joint investment in rail and port infrastructure, both parties aim to maximize transport capacity and ensure the punctuality and safety of operations.

5.1.3. Government or Public Sector

- At the public policy level, there is a perception of insufficient support from the national government to strengthen the port. The absence of clear policies and adequate regulatory frameworks to encourage investment in infrastructure and technology has been a recurring obstacle for Santa Marta, preventing it from achieving sustained growth. The national government could focus its efforts on improving the port’s energy efficiency, promoting digitalization, and adopting sustainable technologies to enhance its long-term competitiveness.

- The concrete and specific implementation of public policies should be carried out along two paths. First, we propose the introduction of specific tax incentives to encourage private investment in sustainable port technologies, such as cold chain electrification and low-emission handling equipment. Second, we outline a roadmap for Public–Private Partnerships (PPPs) to improve intermodal connectivity, particularly rail and road access to the port. This proposal is framed within the legal and institutional context of Colombia’s Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) Law 1508 of 2012, which ensures regulatory harmonization and viability.

5.2. Open-Ended Responses and Recommendations

- Tourism and Cruise Ship TrafficThe Port of Santa Marta serves not only as a commercial gateway but also as an important hub for international cruise tourism. While this dual functionality supports the city’s broader economic base, it creates operational tensions. Cruise ship arrivals frequently occupy berths and terminal resources otherwise designated for container operations, causing delays and inefficiencies. A dedicated berth or a defined cruise schedule—possibly coordinated with container ship rotations—would allow for the better separation of functions and optimized berth utilization.

- Empty Container Handling SchedulesOne of the recurring inefficiencies identified in the port’s operational structure is the lack of predefined schedules for handling empty containers. This results in unpredictable peaks in yard occupation and truck congestion. Implementing fixed time slots or window scheduling for empty container movements would not only increase terminal efficiency, but also facilitate better planning for inland logistics operators and reduce gate congestion.

- Investment in Superstructure and Terminal EquipmentCurrent infrastructure constraints, particularly the limited availability of modern container handling equipment such as ship-to-shore cranes, restrict the terminal’s ability to scale operations or handle larger vessels. Strategic investment in superstructure—especially in post-Panamax cranes, automated stacking systems, and cold chain infrastructure—would enhance handling capacity, reduce turnaround times, and make the terminal more attractive to major shipping lines.

- Security and Road Access InfrastructureSecurity and access limitations remain major concerns for shippers and port users. The access road infrastructure leading to the port is not only insufficient in capacity but also poses safety risks due to poor lighting, limited surveillance, and vulnerability to theft. Improving physical security, implementing smart surveillance systems, and expanding road lanes or creating segregated cargo corridors could substantially increase the reliability and attractiveness of the port’s hinterland connectivity.

- Enhancing Agricultural Export TrafficSanta Marta is located near some of Colombia’s most productive agricultural regions. Increasing containerized agricultural exports—particularly in cold chain commodities such as bananas, avocados, and palm oil—represents a strategic opportunity to boost regional economic integration and increase the port’s cargo diversity. Tailored incentives for agro-exporters, as well as infrastructure for perishable goods handling, could consolidate this segment as a competitive advantage.

- Conflict Between Coal and Container TrafficCurrently, the coexistence of coal export operations and containerized cargo in the same port environment presents a significant operational and environmental conflict. Coal handling generates high levels of dust and particulate pollution, which pose a threat to containerized cargo—especially food products and pharmaceuticals, which require strict sanitary conditions. In the medium term, authorities and concessionaires should evaluate the possibility of segregating or even relocating coal operations outside of container handling areas to reduce contamination risks and enhance the port’s appeal to high-value, sensitive cargo.

5.3. Limitations of the Proposed Framework

The proposed framework has three main limitations. (i) Sensitivity to the perceptual scale: While L1 regression mitigates the influence of outliers, the results still depend on the experts’ use of the −2, +2 scale. This was partially mitigated by z-standardizing each respondent’s matrix. (ii) Static snapshot: Porter’s Diamond captures structural competitiveness, but not short-term shocks such as Panama Canal capacity constraints or fuel price volatility. Future work could combine residual analysis with system dynamics simulation. (iii) Single-port focus: While Cartagena and Barranquilla serve as comparative benchmarks, expanding the sample to include major LAC hubs (e.g., Kingston and Colón) would improve external validity (but may be a subject of a subsequent study). (iv) Regarding survey bias mitigation, we could employ stratified purposive sampling such that each functional group (terminal operator, customs broker, rail supplier, etc.) is proportionally represented using some complementary methodology, or assess internal consistency.

6. Conclusions

Through a detailed analysis of standardized survey data and robust statistical modeling, this study identifies key interactions between port activities and competitiveness factors. The findings—based primarily on stakeholder perceptions—highlight both the strengths and weaknesses in container operations at the Port of Santa Marta. This evidence-based approach provides actionable insights for port authorities, supporting more efficient decision-making, targeted interventions, and long-term strategic planning.

Santa Marta is a vital container terminal for Colombia, particularly for agricultural exports. However, in terms of size, equipment, and the number of shipping lines serviced, it is smaller and less equipped than Cartagena and some of the major Caribbean ports such as Colon and Kingston. Its efficiency and competitiveness are notable in handling specialized cargo, but it does not match the overall capacity and volume handling of larger ports in the region.

The analysis based on the applied methodology provides a comprehensive understanding of the competitive landscape of the Port of Santa Marta. By identifying key strengths in infrastructure, technology, and human capital, as well as areas needing improvement such as road transport and governmental support, the port can strategically enhance its operations and competitive positioning. These insights serve as a valuable guide for future research and strategic planning for port directors.

7. Competitiveness Assessment

The Extended Diamond Model of Porter effectively identifies the competitive advantages and disadvantages of the Santa Marta container terminal, providing a comprehensive framework for assessing port performance. By integrating strategic, institutional, operational, and technological dimensions, this model reveals both the internal capabilities and external constraints that influence the port’s competitiveness. A summary can be found in Table 13.

Table 13.

Matrix of key competitive drivers and strategic priorities for the Port of Santa Marta. Sources: Authors.

While this study primarily compares Santa Marta with its closest national competitors—Cartagena and Barranquilla—future research could benefit from a broader comparative approach that includes leading ports in Latin America and the Caribbean, such as Kingston (Jamaica), Colón (Panama), and Callao (Peru). These ports serve as key transshipment and export platforms in their respective subregions and offer valuable benchmarks in areas such as connectivity, technological innovation, governance models, and service diversification. Incorporating such comparisons would allow Santa Marta’s performance to be assessed not only within the Colombian port system but also in the wider maritime logistics landscape of the Americas. This expanded perspective would support more robust policy recommendations and strengthen the port’s potential role as a competitive, resilient, and sustainable hub in the Western Hemisphere.

Outlook: By addressing these challenges and taking advantage of all its strengths, the Port of Santa Marta could improve its participation in the international market and its competitiveness, becoming the most attractive port of entry and exit for Colombia’s maritime trade. The implementation of strategic recommendations is vital to achieving these objectives, ensuring sustained growth and development in the region.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.d.M.C.J. and J.J.R.A.; Methodology, M.d.M.C.J., J.J.R.A. and A.d.S.P.N.; Software, J.J.R.A. and A.d.S.P.N.; Val-idation, M.d.M.C.J., J.J.R.A. and A.d.S.P.N.; Formal Analysis, M.d.M.C.J., J.J.R.A. and A.d.S.P.N.; Investigation, J.J.R.A. and A.d.S.P.N.; Re-sources, J.J.R.A. and A.d.S.P.N.; Data Curation, J.J.R.A. and A.d.S.P.N.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, J.J.R.A. and A.d.S.P.N.; Writing—Review & Editing, M.d.M.C.J. and J.J.R.A.; Visualization, M.d.M.C.J. and J.J.R.A.; Supervision, M.d.M.C.J. and J.J.R.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper. No personal or financial relationships could have appeared to influence the interpretation or presentation of the research findings.

Appendix A

Matrix of Competitiveness Structure based on The Extend Diamond Model of Porter.

References

- Kellett, P. City profile Santa Marta. Pergamon 1997, 14, 393–402. [Google Scholar]

- SuperTransporte. Tráfico Portuario en Colombia; SuperTransporte: Bogotá, DC, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.supertransporte.gov.co/index.php/superintendencia-delegada-de-puertos/estadisticas-trafico-portuario-en-colombia/ (accessed on 24 May 2024).

- Congress of the Republic of Colombia. Law 01 of 1991; Congress of the Republic of Colombia: Bogotá, DC, USA, 1991. Available online: https://www.funcionpublica.gov.co/eva/gestornormativo/norma.php?i=67055 (accessed on 24 July 2024).

- Cano-Leiva, J.; Cantos-Sanchez, P.; Sempere-Monerris, J.J. The effect of privately managed terminals on the technical efficiency of the Spanish port system. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2023, 13, 101026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, L.; Cantillo, V.; Arellana, J. Assessing the impact of major infrastructure projects on port choice decision: The Colombian case. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2019, 120, 132–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serebrisky, T.; Sarriera, J.M.; Suárez-Alemán, A.; Araya, G.; Briceño-Garmendía, C.; Schwartz, J. Exploring the drivers of port efficiency in Latin America and the Caribbean. Transp. Policy 2016, 45, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bichou, K.; Gray, R. A critical review of conventional terminology for classifying seaports. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2005, 39, 75–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garza, N.; Ovalle, M.C. Tourism and housing prices in Santa Marta, Colombia: Spatial determinants and interactions. Habitat Int. 2019, 87, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, H.; Chang, C.T. Beyond throughput: Evaluating maritime port competitiveness using MABAC and Bayesian methods. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2024, 192, 110248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tongzon, J.; Heng, W. Port privatization, efficiency and competitiveness: Some empirical evidence from container ports (terminals). Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2005, 39, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haezendonck, E.; Pison, G.; Rousseeuw, P.; Struyf, A.; Verbeke, A. The Competitive Advantage of Seaports. Int. J. Marit. Econ. 2000, 2, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, M.; Coronado, D.; Cerban, M.M. Port competitiveness in container traffic from an internal point of view: The experience of the Port of Algeciras Bay. Marit. Policy Manag. 2007, 34, 501–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, M.; Coronado, D.; Del Mar Cerban, M. Bunkering competition and competitiveness at the ports of the Gibraltar Strait. J. Transp. Geogr. 2011, 19, 911–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaliszewski, A.; Kozłowski, A.; Dąbrowski, J.; Klimek, H. Key factors of container port competitiveness: A global shipping lines perspective. Mar. Policy 2020, 117, 103896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.T.; Talley, W.K. Port Competitiveness, Efficiency, and Supply Chains: A Literature Review. Transp. J. 2019, 58, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilmsmeier, G.; Hoffmann, J.; Sanchez, R.J. The Impact of Port Characteristics on International Maritime Transport Costs. Res. Transp. Econ. 2006, 16, 117–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, G.T.; Roe, M.; Dinwoodie, J. Evaluating the Competitiveness of Container Ports in Korea and China. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2008, 42, 910–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parola, F.; Risitano, M.; Ferretti, M.; Panetti, E. The drivers of port competitiveness: A critical review. Transp. Rev. 2017, 37, 116–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya, J.M.; Valero, M.F. Port choice in container market: A literature review. Transp. Rev. 2017, 37, 300–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Chen, F.; Zhang, J. Relationships among port competition, cooperation and competitiveness: A literature review. Transp. Policy 2022, 118, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullinane, K.; Fei, W.T.; Cullinane, S. Container terminal development in mainland China and its impact on the competitiveness of the port of Hong Kong. Transp. Rev. 2004, 24, 33–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trade, U.N.; Unctad, D. Review of Maritime Transport Executive Summary. Available online: https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/rmt2020_en.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2024).

- Michael, O.O. Assessing the contribution of containerization to the development of Western Ports, Lagos Nigeria. J. Int. Logist. Trade 2019, 17, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaliszewski, A.; Kozłowski, A.; Dąbrowski, J.; Klimek, H. LinkedIn survey reveals competitiveness factors of container terminals: Forwarders’ view. Transp. Policy 2021, 106, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rugman, A.M.; Verbeke, A. Foreign Subsidiaries and Multinational Strategic Management: An Extension and Correction of Porter’s Single Diamond Framework. MIR Manag. Int. Rev. 1993, 33, 71–84. [Google Scholar]

- Baştuğ, S.; Haralambides, H.; Esmer, S.; Eminoğlu, E. Port competitiveness: Do container terminal operators and liner shipping companies see eye to eye? Mar. Policy 2022, 135, 104866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pabón-Noguera, A.; Carrasco-García, M.G.; Ruíz-Aguilar, J.J.; Rodríguez-García, M.I.; Cerbán-Jimenez, M.; Domínguez, I.J.T. Multicriteria Decision Model for Port Evaluation and Ranking: An Analysis of Container Terminals in Latin America and the Caribbean Using PCA-TOPSIS Methodologies. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Roe, M. Port Competition. In Maritime Container Port Security; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 59–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.; Hyodo, T. Assessment of port efficiency within Latin America. J. Shipp. Trade 2022, 7, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya-Rojas, G.A.; García, M.A.; Bello-Escobar, S.; Singh, K.P. Analysis of the interrelations between biogeographic systems and the dynamics of the Port-Waterfront Cities: Cartagena de Indias, Colombia. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2020, 185, 105055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notteboom, T.E.; Rodrigue, J.P. Port Regionalization: Towards a New Phase in Port Development. Marit. Policy Manag. 2005, 32, 297–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa, D.S.; de Assis Carvalho, M.V.G.S.; de Figueiredo, N.M.; de Moraes, H.B.; Ferreira, R.C.B. The efficiency of container terminals in the northern region of Brazil. Util. Policy 2021, 72, 101278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubert, M.; Rousseeuw, P. Robust regression with both continuous and binary regressors. J. Stat. Plan. Inference 1997, 57, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, E.R.M.; Ríos, E.B.R.; Casasola, D.B.; del, M. Cerbán Jiménez, M. Artisanal fishery in Ecuador. A case study of Manta city and its economic policies to improve competitiveness of the sector. Mar. Policy 2021, 124, 104313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).