Logistical Challenges in Home Health Care: A Comparative Analysis Between Portugal and Brazil

Abstract

1. Introduction

- How do logistical structures and operations in HHC differ between Brazil and Portugal?

- What performance indicators highlight inefficiencies or good practices in each context?

- How can these insights inform policy and operational improvements in public HHC delivery?

2. Research Methodology

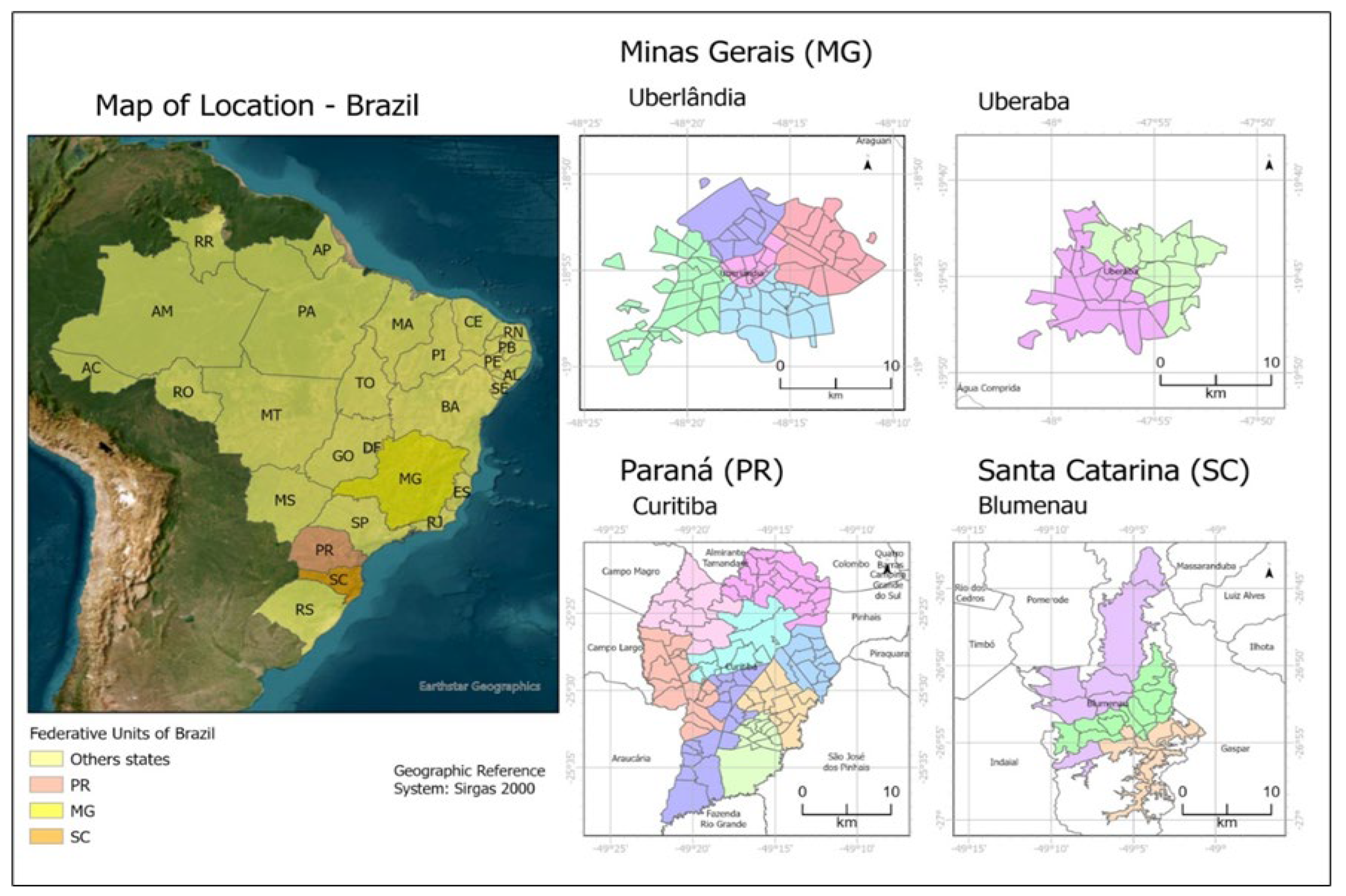

2.1. Study Setting and Design

2.2. Data Collection

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Organizational Structure and Management

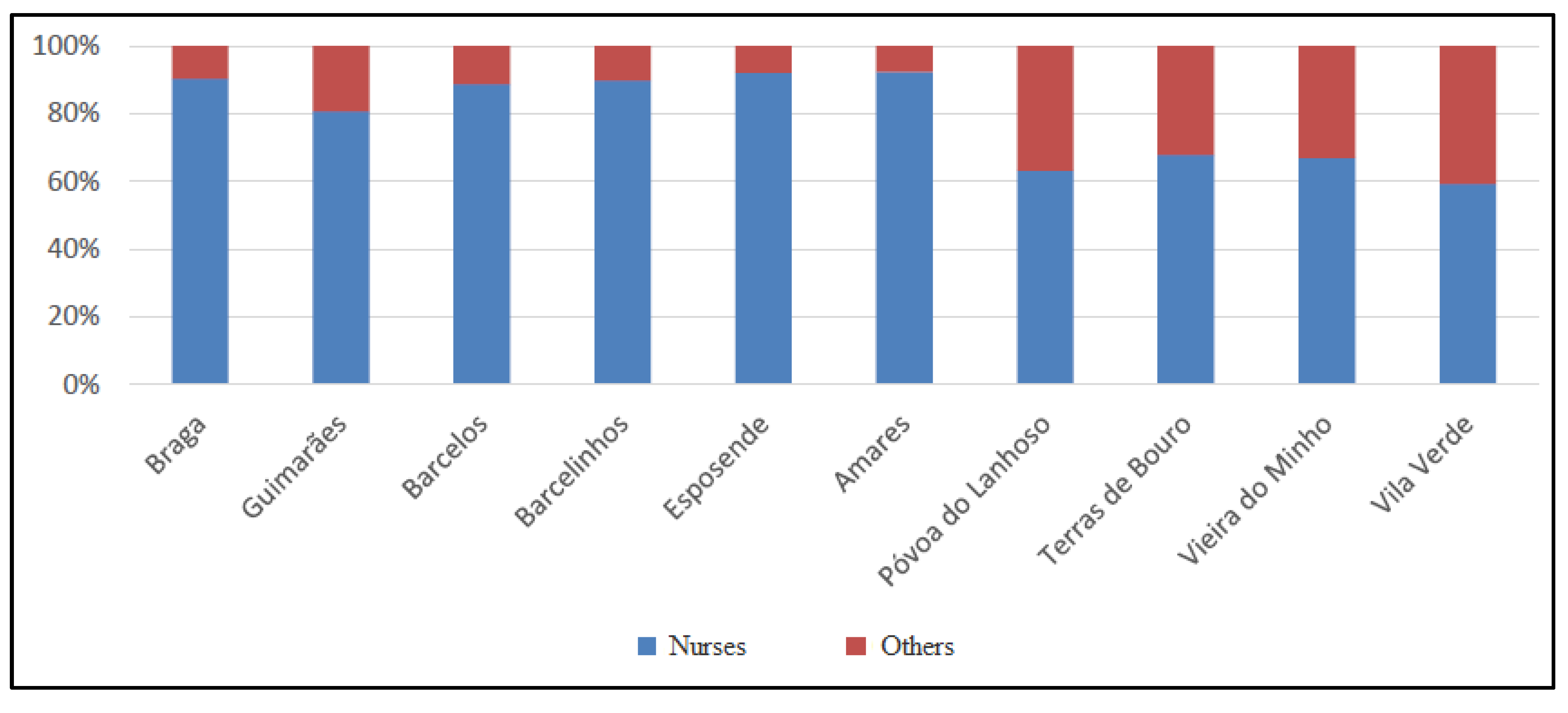

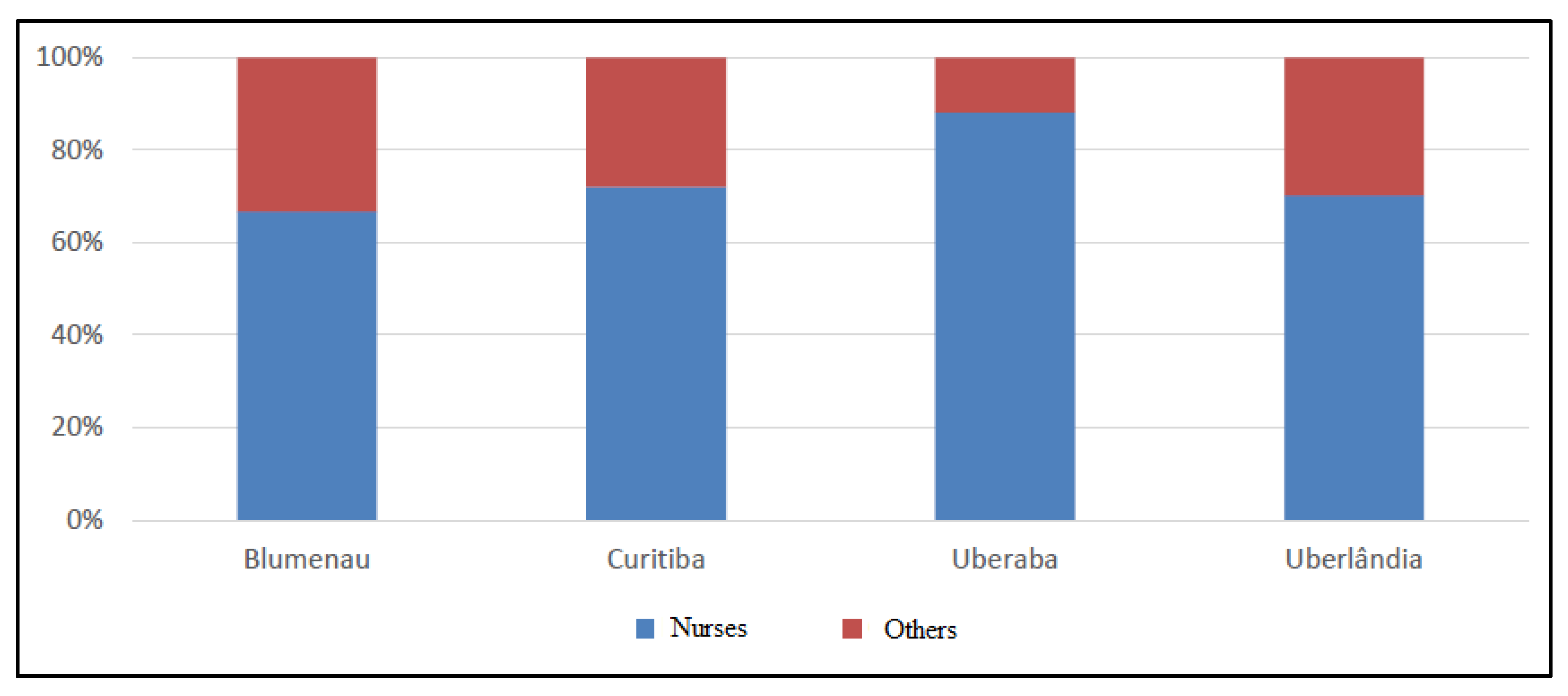

3.2. Team Composition

3.3. Facilities and Fleet Management

3.4. Materials Management

3.5. Operations and Productivity of Teams

3.6. Team Productivity

3.7. Costs and Budgets Allocated to the HHC Teams

3.8. Best Practices

4. Lessons from the Pandemic: Strengthening Home Health Care Logistics

5. Conclusions

5.1. Key Conclusions

5.2. Contributions to Theory

5.3. Managerial Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ohta, R.; Ryu, Y.; Kitayuguchi, J.; Gomi, T.; Katsube, T. Challenges and solutions in the continuity of home care for rural older people: A thematic analysis. Home Health Care Serv. Q. 2020, 39, 126–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genet, N.; Boerma, W.G.; Kringos, D.S.; Bouman, A.; Francke, A.L.; Fagerström, C.; Melchiorre, M.G.; Greco, C.; Devillé, W. Home care in Europe: A systematic literature review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2011, 11, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emmesjö, L.; Gillsjö, C.; Dahl Aslan, A.K.; Hallgren, J. Patients’ and next of kin’s expectations and experiences of a mobile integrated care model with a home health care physician—A qualitative thematic study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UN News. ‘Ageing Well Must Be Global Priority’, Warns UN Health Agency in New Study. UN News. 2016. Available online: https://news.un.org/en/story/2014/11/483012#.VFyq6_nF-z4 (accessed on 21 March 2025).

- Puchia, C.; Jara, P. Enfermería y el cuidado domiciliario de los mayores en la era de la globalización. Enferm. Univ. 2015, 12, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahrichi, N.; Lapierre, S.D.; Hertz, A.; Talib, A.; Bouvier, L. Analysis of a territorial approach to the delivery of nursing home care services based on historical data. J. Med Syst. 2006, 30, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmussen, M.S.; Justesen, T.; Dohn, A.; Larsen, J. The Home Care Crew Scheduling Problem: Preference-based visit clustering and temporal dependencies. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2012, 219, 598–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; Chin, K.-S.; Fu, C.; Tsui, K.-L. An effective greedy method for the Meals-On-Wheels service districting problem. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2017, 106, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACSS Monitorização da Rede Nacional de Cuidados Continuados Integrados (RNCCI). Lisboa. 2015. Available online: http://www.acss.min-saude.pt/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Relatorio-de-monitorizacao-anual-de-2015.pdf (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- SAGE Sala de Apoio à Gestão Estratégica. SAGE. 2019. Available online: http://sage.saude.gov.br/# (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Mankowska, D.S.; Meisel, F.; Bierwirth, C. The home health care routing and scheduling problem with interdependent services. Health Care Manag. Sci. 2014, 17, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutierrez, E.V.G.; Vidal, C.J. A Home Health Care Districting Problem in a Rapid-Growing City. Ing. Univ. 2015, 19, 87–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Alasalvar, F.E.; Yilmaz, M. Analysis of home care nurses’ workload: A time-motion study. Home Health Care Serv. Q. 2023, 42, 311–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez, E.V.; Vidal, C.J. Home Health Care Logistics Management: Framework and Research Perspectives. Int. J. Ind. Eng. Manag. 2013, 4, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RNCCI Plano de Desenvolvimento da RNCCI 2016–2019. Ministério da Saúde. 2015. Available online: https://www.sns.gov.pt/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Plano-de-desenvolvimento-da-RNCCI.pdf (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- INE Censos 2011—Resultados Provisórios. INE. 2011. Available online: https://www.ine.pt/xurl/pub/122073978 (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- Portal SNS RNCCI | Norte Investe 49 M€–SNS. Portal SNS. 2018. Available online: https://www.sns.gov.pt/noticias/2018/01/30/rncci-norte-investe-49-me/ (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- Silva, K.L.; de Sena, R.R.; Seixas, C.T.; Feuerwerker, L.C.M.; Merhy, E.E. Atenção domiciliar como mudança do modelo tecnoassistencial. Rev. Saude Publica 2010, 44, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasil PORTARIA No 825, DE 25 DE ABRIL DE 2016. Ministério da Saúde. 2016. Available online: http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/gm/2016/prt0825_25_04_2016.html (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- Brasil PORTARIA No 963, DE 27 DE MAIO DE 2013. Ministério da Saúde. 2013. Available online: https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/gm/2013/prt0963_27_05_2013.html (accessed on 9 February 2025).

- Filipe, M.M.L. Contributo para um Modelo de Contratualização de Cuidados em Contexto Domiciliário: Estudo Exploratória sobre os Custos de Funcionamento das ECCI. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade Católica Portuguesa, Porto, Portugal, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadi, A.; Fathollahi-Fard, A.M.; Karimi, B.; Hajiaghaei-Keshteli, M. Sustainable and Robust Home Healthcare Logistics: A Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Symmetry 2022, 14, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathollahi-Fard, A.M.; Ahmadi, A.; Karimi, B.; Hajiaghaei-Keshteli, M. Multi-Objective Optimization of Home Healthcare with Working-Time Balancing and Care Continuity. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos Ximenes, T.S.; de Oliveira Silva, A.C.; de Martino, G.P.; Emiliano, W.M.; Menzori, M.; Meyer, Y.A.; Molina Júnior, V.E. Vehicular Traffic Flow Detection and Monitoring for Implementation of Smart Traffic Light: A Case Study for Road Intersection in Limeira, Brazil. Futur. Transp. 2024, 4, 1388–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ACES | HHC Teams | Workload (Hours/Month) | Number of Visits/Month | Hours/Visit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alto Ave | Guimarães | 1004 | 296 | 3.39 |

| Taipas | 260 | 80 | 3.26 | |

| Cávado I | Braga—Carandá | 668 | 201 | 3.33 |

| Braga—Infias | 542 | 192 | 2.83 | |

| Braga—Maximinos | 638 | 164 | 3.89 | |

| Cávado II | Amares | 564 | 73 | 7.73 |

| Póvoa do Lanhoso | 640 | 43 | 14.89 | |

| Terras de Bouro | 529 | 65 | 8.15 | |

| Vieira do Minho | 623 | 127 | 4.9 | |

| Vila Verde | 833 | 165 | 5.05 | |

| Cávado III | Barcelinhos | 677 | 113 | 5.99 |

| Barcelos | 855 | 213 | 4.01 | |

| Esposende | 942 | 151 | 6.24 |

| Cities | HHC Teams | Workload (Hours/Month) | Number of Visits/Month | Hours/Visit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blumenau | HHC 1 | 1042 | 68 | 15.32 |

| HHC 2 | 1042 | 93 | 10.20 | |

| HHC 3 | 1042 | 162 | 6.43 | |

| Curitiba | HHC 1 | 1085 | 68 | 15.96 |

| HHC 2 | 1085 | 183 | 5.93 | |

| HHC 3 | 1085 | 57 | 19.04 | |

| HHC 4 | 1085 | 51 | 21.27 | |

| HHC 6 | 1085 | 176 | 6.16 | |

| HHC 7 | 1085 | 152 | 7.14 | |

| HHC 8 | 1085 | 130 | 8.35 | |

| HHC 9 | 1085 | 150 | 7.23 | |

| Uberaba | HHC A | 737.80 | 135 | 5.47 |

| HHC B | 1042 | 162 | 6.43 | |

| Uberlândia | Center HHC | 1020 | 264 | 3.86 |

| East HHC | 1020 | 272 | 3.75 | |

| North HHC | 1020 | 206 | 4.95 | |

| West HHC | 1020 | 197 | 5.18 | |

| Southern HHC | 1020 | 246 | 4.15 |

| Indicators | Best Practices Pertaining (Preferably in the Highlighted Case) | |

|---|---|---|

| Portugal | Brazil | |

| Workload of other types of professionals |  | |

| Territorial coverage of services |  | |

| Distance traveled |  | |

| Multidisciplinary team |  | |

| Fleet management |  | |

| Integration among teams |  | |

| Inventory management |  | |

| Number of patient slots |  | |

| Annual budget |  | |

| Productivity |  | |

| Information recording |  | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Emiliano, W.M.; Mansano Schlosser, T.C.; Molina Júnior, V.E.; Telhada, J.; Meyer, Y.A. Logistical Challenges in Home Health Care: A Comparative Analysis Between Portugal and Brazil. Logistics 2025, 9, 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/logistics9030101

Emiliano WM, Mansano Schlosser TC, Molina Júnior VE, Telhada J, Meyer YA. Logistical Challenges in Home Health Care: A Comparative Analysis Between Portugal and Brazil. Logistics. 2025; 9(3):101. https://doi.org/10.3390/logistics9030101

Chicago/Turabian StyleEmiliano, William Machado, Thalyta Cristina Mansano Schlosser, Vitor Eduardo Molina Júnior, José Telhada, and Yuri Alexandre Meyer. 2025. "Logistical Challenges in Home Health Care: A Comparative Analysis Between Portugal and Brazil" Logistics 9, no. 3: 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/logistics9030101

APA StyleEmiliano, W. M., Mansano Schlosser, T. C., Molina Júnior, V. E., Telhada, J., & Meyer, Y. A. (2025). Logistical Challenges in Home Health Care: A Comparative Analysis Between Portugal and Brazil. Logistics, 9(3), 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/logistics9030101