Global Supply Chains Made Visible through Logistics Security Management

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Literature

3. Research Focus and Methodology

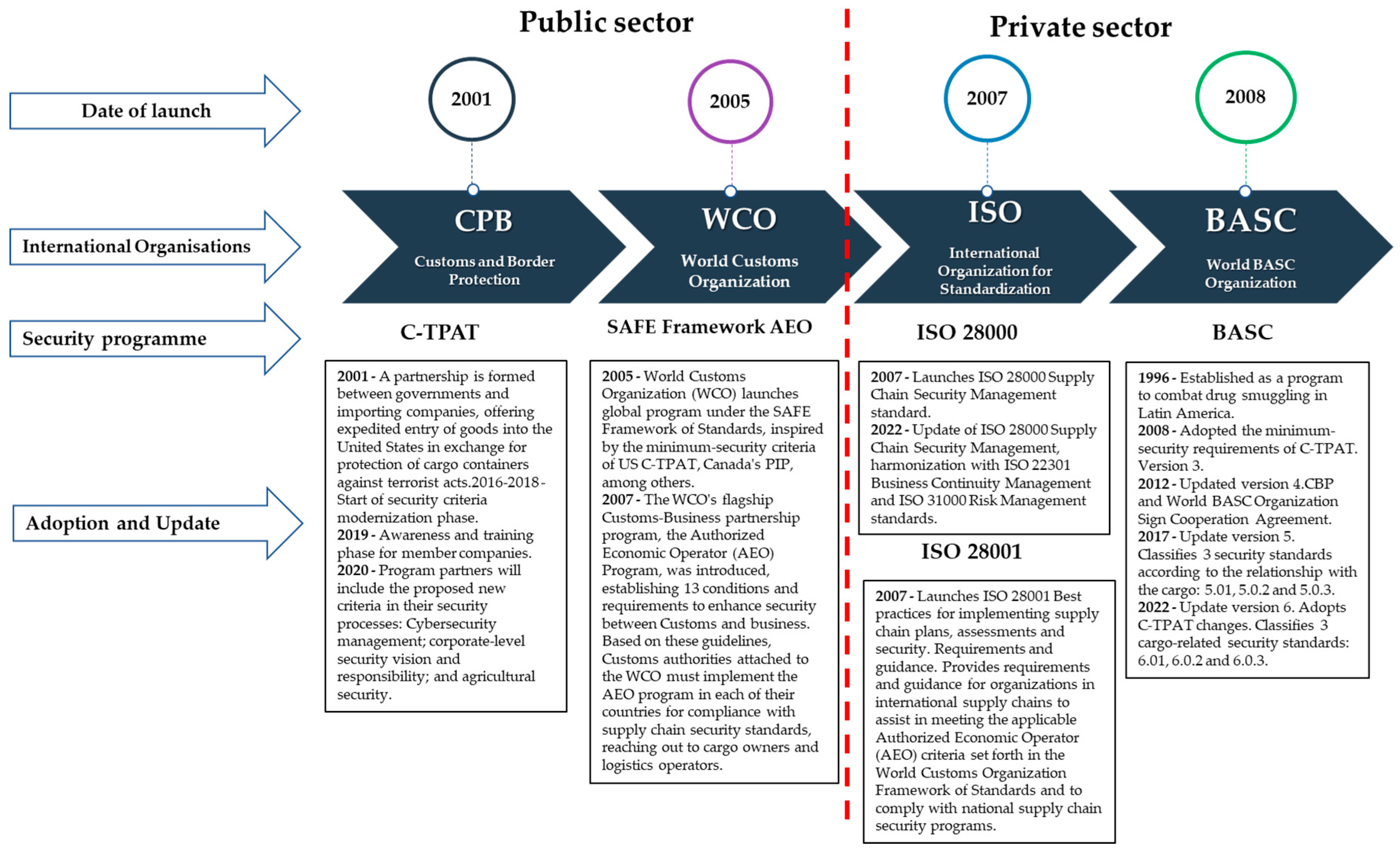

4. Description of the Analyzed Logistics Security Programs

- (1)

- Customs Trade Partnership Against Terrorism (C-TPAT) program of the U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP);

- (2)

- Business Alliance for Secure Commerce (BASC) program of the BASC World Organization (WBO);

- (3)

- Authorized Economic Operator (AEO) program of the World Customs Organization (WCO);

- (4)

- International Standards for Supply Chain Security Management ISO 28000 and ISO 28001 of the International Organization for Standardization (ISO).

5. Main Security Risks in Global Supply Chains

6. Findings

6.1. Comparison and Analysis of the Content of Logistics Security Programs

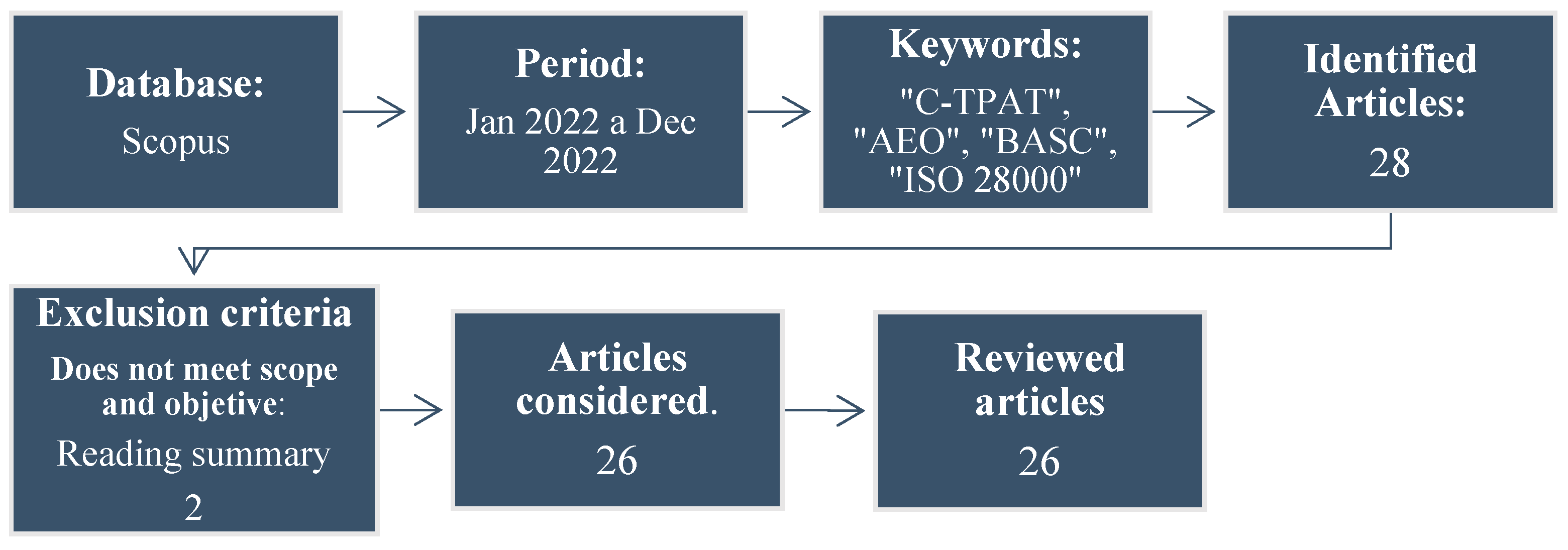

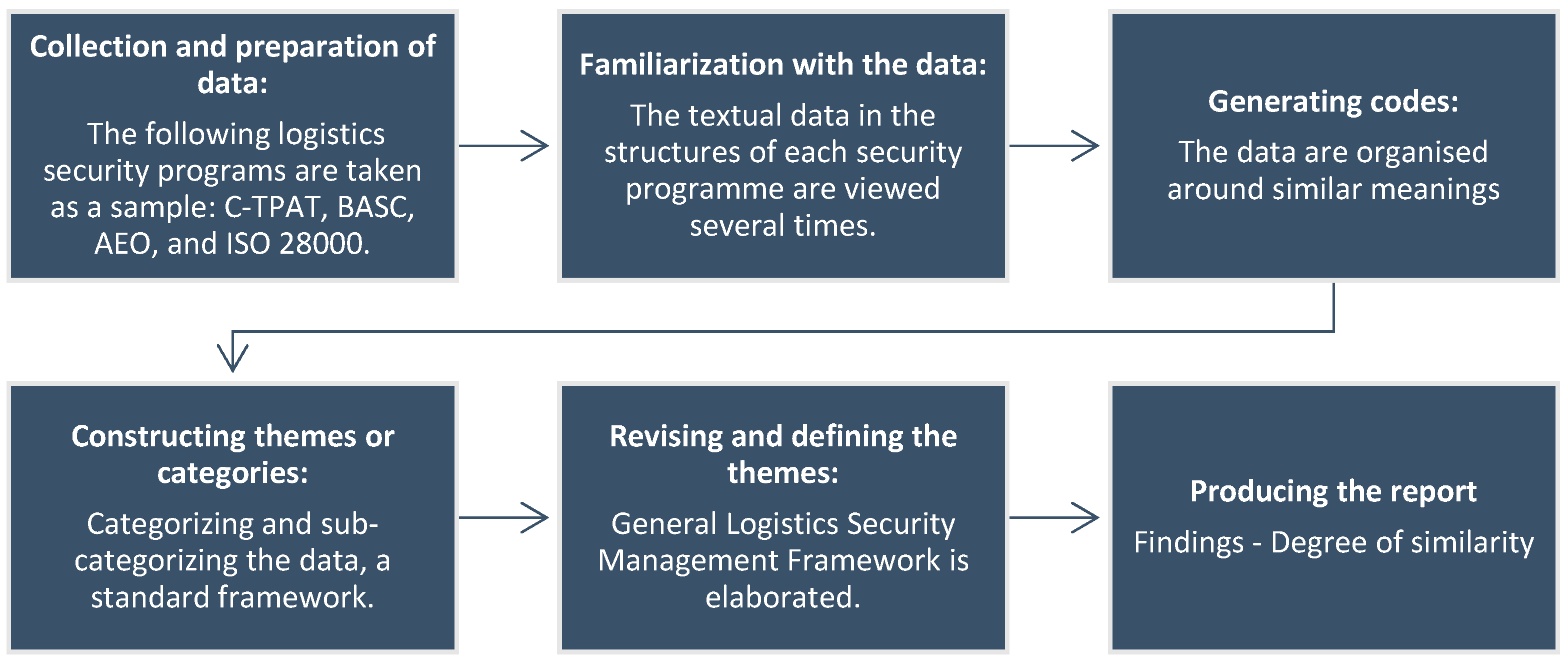

- Phase 1: Collection and preparation of data: In this phase, data from the four security programs C-TPAT, BASC, AEO, and ISO 28000 are collected and prepared, using publicly available sources of information from international bodies, and a description of their regulatory structure is provided in chapters representing the security levels of each program.

- Phase 2: Familiarization with the data: The textual data in the structures of each security program is viewed several times. This allows you to become familiar with the information, recognize variations, and understand the context.

- Phase 3: Generating codes: At this stage, the data are organized around similar meanings, coded under a deductive orientation, assigning labels called chapters and security requirements. Not all security program requirements are included in their entirety as they are irrelevant to the analysis.

- Phase 4: Constructing themes or categories: Categories are created using the axial coding process. By categorizing and sub-categorizing the data, a standard framework of security levels is constructed for qualitative analysis.

- Phase 5: Revising and defining the themes: Based on the standard framework of security levels, the General Logistics Security Management Framework is elaborated with an assessment for quantitative analysis of the eight chapters and 40 security requirements in the four programs. Defining an evaluation scale, if it complies it is 1, and if it does not comply, it is 0.

- Phase 6: Producing the report: This final phase presents the results of the thematic content analysis, represented in degrees of similarity of the four logistics security programs.

6.2. Benefits of Implementing a Logistics Security Program

6.3. Monetary Costs for the Implementation of a Logistics Security Program

7. Open Research Problems

- This study can be used to establish compatible security programs or develop global security standards, such as the proposal for a standardized regional AEO program for Latin America and the Caribbean, like the C-TPAT and BASC programs, with a single structure that organizes the chapters and minimum-security requirements in a standardized manner for implementation by any WCO member in the region, could be considered for future discussion and research. This would facilitate a clear language to manage homogeneous threats at the regional level and the operations of certified companies and intra-regional trade, as well as the promotion of Mutual Recognition Agreements (MRAs) for greater benefits.

- The private sector benefits from the BASC and ISO programs can be considered for future research studies as a source of customer-facing competitive advantages to secure and optimize global operations.

- There is scope for a case study reviewing the benefits of the AEO program proposed by a country’s customs authority versus the perception of benefits received by cargo-owning companies and logistics service operators that adhere to this initiative.

- The adoption of a maturity model to assess logistics security systems in global supply chains in Latin America and the Caribbean could derive opportunities to improve security and resilience to future disruptions in the context of supply chain security risk management.

- Another opportunity is the application of logical and systematic methods for supply chain security risk assessment.

8. Managerial Implications, Discussion, and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kalaiarasan, R.; Olhager, J.; Agrawal, T.K.; Wiktorsson, M. The ABCDE of supply chain visibility: A systematic literature review and framework. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2022, 248, 108464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boile, M.; Sdoukopoulos, L. Supply chain visibility and security—The SMART-CM project solution. Int. J. Shipp. Transp. Logist. 2014, 6, 280–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barratt, M.; Barratt, R. Exploring internal and external supply chain linkages: Evidence from the field. J. Oper. Manag. 2011, 29, 514–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, M.; De Souza, R.; Zhang, A.N.; He, W.; Tan, P.S. Supply chain visibility: A decision making perspective. In Proceedings of the 4th IEEE Conference on Industrial Electronics and Applications, ICIEA, Xi’an, China, 25–27 May 2009; pp. 2546–2551. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, B.D.; Roh, J.; Tokar, T.; Swink, M. Leveraging supply chain visibility for responsiveness: The moderating role of internal integration. J. Oper. Manag. 2013, 31, 543–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.-C.; Goh, M. A multi-objective approach to supply chain visibility and risk. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2014, 233, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.-C. Risk management of Taiwan’s maritime supply chain security. Saf. Sci. 2011, 49, 382–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikoofal, M.E.; Pourakbar, M.; Gumuz, M. Securing containerized supply chain through public and private partnership. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2023. early view. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya-Torres, J.R.; Muñuz-Villamizar, A.F.; Mejía-Argueta, C. Mapping research in logistics and supply chain management during COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2023, 26, 421–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manuj, I.; Mentzer, J. Global supply chain risk management strategies. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2008, 38, 192–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya-Torres, J.R. Managing Disruptions in Supply Chains. In Service Oriented, Holonic and Multi-Agent Manufacturing Systems for Industry of the Future. SOHOMA 2021. Studies in Computational Intelligence; Trentesaux, D., Borangiu, T., Leitão, P., Jimenez, J.F., Montoya-Torres, J.R., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; Volume 987, pp. 272–284. [Google Scholar]

- Hintsa, J.; Gutiérrez, X.; Weiser, P.; Hameri, A.-P. Supply Chain Security Management: An overview. Int. J. Logist. Syst. Manag. 2009, 5, 344–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asamoah, D.; Nuertey, D.; Agyei-Owusu, B.; Acquah, I. Antecedents and outcomes of supply chain security practices: The role of organizational security culture and supply chain disruption occurrence. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2022, 39, 1059–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donner, M.; Kruk, C. Supply Chain Security Guide; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2009; Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10986/28128 (accessed on 28 May 2023).

- Pérez, G. Seguridad de la Cadena Logística Terrestre en América Latina; Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (Cepal): Santiago, Chile, 2013; p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 31000:2018; Risk Management Guidelines. International Standard Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. Available online: https://www.iso.org/obp/ui#iso:std:iso:31000:ed-2:v1:en (accessed on 28 May 2023).

- Supply Chain Risk Leadership Council (SCRLC). Available online: http://www.scrlc.com/articles/Supply_Chain_Risk_Management_A_Compilation_of_Best_Practices_final%5B1%5D.pdf (accessed on 28 May 2023).

- ICS 731-01. Intelligence Community Standard. Available online: https://www.dni.gov/files/NCSC/documents/supplychain/ICS%20731-01%20Supply%20Chain%20Criticality%20Assessments.pdf (accessed on 29 May 2023).

- Svensson, G. A conceptual framework for the analysis of vulnerability in supply chains. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2000, 30, 731–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jüttner, U.; Peck, H.; Christopher, M. Supply chain risk management: Outlining an agenda for future research. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2003, 6, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peck, H.; Christopher, M. Building the resilient Supply Chain. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2004, 15, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, C. Perspectives in supply chain risk management. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2006, 103, 451–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, Z.; Lueg, J.E.; LeMay, S.A. Supply chain security: An overview and research agenda. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2008, 19, 254–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.; Goldsby, T.J. Supply chain risk: A review and typology. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2009, 20, 97–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnyk, S.A.; Rodrigues, A.; Ragatz, G.L. Using simulation to investigate supply chain disruptions. In Supply Chain Risk—A Handbook of Assessment, Management, and Performance; Zsidisin, G.A., Ritchie, B., Eds.; International Series of Operations Research & Management Sciences; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; Volume 124, pp. 103–122. [Google Scholar]

- Ponomarov, S.Y.; Holcomb, M.C. Understanding the concept of supply chain resilience. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2009, 20, 124–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfohl, H.-C.; Köhler, H.; Thomas, D. State of the art in supply chain risk management research: Empirical and conceptual findings and a roadmap for the implementation in practice. Logist. Res. 2010, 2, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieland, A. Selecting the right supply chain based on risks. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2013, 24, 652–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz, A.; Dunbar, M. On the quantification of operational supply chain resilience. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2015, 53, 6736–6751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tordecilla, R.D.; Juan, A.A.; Montoya-Torres, J.R.; Quintero-Araujo, C.L.; Panadero, J. Simulation-Optimization Methods for Designing and Assessing Resilient Supply Chain Networks under Uncertainty Scenarios: A Review. Simul. Model. Pract. Theory 2021, 106, 102166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, Z.; Garver, M.S.; Richey, R.G., Jr. Security capability and logistics service provider selection: An adaptive choice study. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2019, 49, 330–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, X.; Hintsa, J. Voluntary supply chain security programs: A systematic comparison. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Systems, Logistics and Supply Chain (ILS2006), Lyon, France, 15–17 May 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Tranfield, D.; Denyer, D.Y.; Smart, P. Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. Br. J. Manag. 2003, 14, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, W.J.; Melnyk, S.A. The impact of emerging institutional norms on adoption timing decisions: Evidence from C-TPAT-A government antiterrorism initiative. Strateg. Manag. J. 2012, 33, 860–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnyk, S.A.; Ritchie, W.J.; Calantone, R.J. The case of the C-TPAT border security initiative: Assessing the adoption/persistence decisions when dealing with a novel, institutionally driven administrative innovation. J. Bus. Logist. 2013, 34, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voss, M.D.; Williams, Z. Public-private partnerships and supply chain security: C-TPAT as an indicator of relational security. J. Bus. Logist. 2013, 34, 320–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, T.J.F. Application of discriminant analysis to assess productivity as a result from the BASC certification in Cartagena companies. Account. Adm. 2014, 59, 43–62. [Google Scholar]

- Schramm, H.-J. Who benefits most from AEO certification? An Austrian perspective. World Cust. J. 2015, 9, 59–67. [Google Scholar]

- Blos, M.F.; Hoeflich, S.L.; Dias, E.M.; Wee, H.-M. A note on supply chain risk classification: Discussion and proposal. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2016, 53, 1568–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.Z.; Melnyk, S.A.; Ritchie, W.J.; Flynn, B.F. Why be first if it doesn’t pay? The case of early adopters of C-TPAT supply chain security certification. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2016, 36, 1161–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang-Bong, K.; Chun, H.-U.; Kwon, S.-H. Impact of application factors of the AEO program on its performance. J. Korea Trade 2016, 20, 332–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, T.J.F. Analysis of the financial efficiency in BASC certified companies through data envelopment analysis: Evidence from Cali—Colombia. In Proceedings of the 27th International Business Information Management Association Conference—Innovation Management and Education Excellence Vision 2020: From Regional Development Sustainability to Global Economic Growth, IBIMA, Milan, Italy, 4–5 May 2016. [Google Scholar]

- The Program Authorized Economic Operator (Brazilian OEA) and the Port Operations: An Exploratory Study with Port Terminals. Available online: http://www.ifac.portafolio.revistaespacios.com/a17v38n21/a17v38n21p17.pdf (accessed on 28 May 2023).

- Karlsson, L. Back to the future of Customs: A new AEO paradigm will transform the global supply chain for the better. World Cust. J. 2017, 11, 23–34. [Google Scholar]

- Bagchi, A.; Paul, J.A. Espionage and the optimal standard of the Customs-Trade Partnership against Terrorism (C-TPAT) program in maritime security. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2017, 262, 89–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houe, T.; Murphy, E. The AEO status as a source of competitive advantage. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2018, 30, 591–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, M.G. Participatory Operational & Security Assessment on homeland security risks: An empirical research method for improving security beyond the borders through public/private partnerships. J. Transp. Secur. 2018, 11, 85–100. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, C.Y.; Sorooshian, S. Possible barriers affecting implementation of ISO28000 for the supply chain. Int. J. Supply Chain. Manag. 2019, 8, 90–97. [Google Scholar]

- Dos Santos Marques, L.G.; Kondrashova, A.; Morini, C. Diving deeper in performance indicators: What do we know about the AEO in Brazil? World Cust. J. 2019, 13, 81–100. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, V.; Ding, X.; Testa, T.M. A case study of drivers, barriers, and company size associated with C-TPAT program. Supply Chain Forum 2019, 20, 332–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erfan, S. The practical implications of AEO on preferential origin certification. Glob. Trade Cust. J. 2019, 14, 479–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ing, W.H.; Sorooshian, S.; Hasan, M. Benefits that attract industry to implement ISO 28000 to secure supply chain. TEM J. 2019, 8, 119–124. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, C.-B.; Chung, I.-S.; Joo, H.-Y. Effects of AEO-MRA on the performance of exporters and importers in Korea. J. Korea Trade 2019, 23, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jażdżewska-Gutta, M.; Grottel, M.; Wach, D. AEO certification—Necessity or privilege for supply chain participants. Supply Chain Manag. 2020, 25, 679–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimon, D.; Madzík, P. Standardized management systems and risk management in the supply chain. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2020, 37, 305–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusrini, E.; Hanim, K. Analysis of compliance and supply chain security risks based on ISO 28001 in a logistic service provider in Indonesia. Int. J. Saf. Secur. Eng. 2021, 11, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusrini, E.; Anggarani, I.; Praditya, T.A. Analysis of Supply Chain Security Management Systems Based on ISO 28001: 2007: Case Study Leather Factory in Indonesia. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 8th International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Applications, ICIEA 2021, Virtual, 23–26 April 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, X.; Lai, K.-H.; Lo, C.K.Y.; Cheng, T.C.E. Supply chain security certification and operational performance: The role of upstream complexity. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2022, 247, 108433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ministerio de Comercio, Industria y Turismo. Informe sobre los acuerdos comerciales vigentes de Colombia. En cumplimiento de la Ley 1868 de 2017, por medio de la cual se establece la entrega del Informe anual sobre el desarrollo, avance y consolidación de los acuerdos comerciales ratificados. MINCIT; 2021; pp. 6–7. Available online: https://www.tlc.gov.co/temas-de-interes/informe-sobre-el-desarrollo-avance-y-consolidacion/documentos/informe-tlc-2023.aspx (accessed on 3 November 2022).

- Chapter Thematic Analysis. Available online: https://sk.sagepub.com/reference/the-sage-handbook-of-qualitative-research-in-psychology/i425.xml (accessed on 3 November 2022).

- Li, T.S. Establishing an integrated framework for security capability development in a supply chain. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2014, 17, 283–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CBP Enforcement Statistics. U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CPB). 2022. Available online: https://www.cbp.gov/ (accessed on 30 January 2023).

- Business Alliance for Secure Commerce (BASC). 2022. Available online: https://wbasco.org/es (accessed on 2 November 2022).

- Boletín FAL C-TPAT y AEO: Las nuevas vías del Comercio Internacional. Available online: https://repositorio.cepal.org/items/f27ff02b-e14d-4aa7-b6d5-5eb5741c1602 (accessed on 30 January 2023).

- Compendium of Authorized Economic Operator Programmes—Ed. 2020. Available online: http://www.wcoomd.org/en/media/newsroom/2020/december/now-available-aeo-compendium-2020-edition.aspx (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- FAC 2022-2; SAFE Framework of Standards. World Customs Organization (WCO): Brussels, Belgium, 2021.

- ISO 28000:2022; Security and Resilience—Security Management Systems—Requirements. International Standard Organization (ISO): Geneve, Switzerland, 2022.

- ISO 28001:2007; Security Management Systems for the Supply Chain—Best Practices for Implementing Supply Chain Security, Assessments and Plans—Requirements and Guidance. International Standard Organization (ISO): Geneve, Switzerland, 2007.

- The ISO Survey of Management System Standard Certifications 2020; International Standard Organization (ISO): Geneve, Switzerland; Available online: https://www.iso.org/the-iso-survey.html. (accessed on 29 May 2023).

- Cranfield School of Management. Supply Chain Vulnerability; Department for Transport, Local Government and the Regions—Department of Trade and Industry: Cranfield, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Meixell, M.J.; Norbis, M. Integrating carrier selection with supplier selection decisions to improve supply chain security. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2012, 19, 711v732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, R.R.; Esqueda, P. Vulnerabilidades de la cadena de suministros: Consideraciones para el caso de América Latina. Acad. Rev. Latinoam. De Adm. 2005, 34, 63–78. [Google Scholar]

- Park, K.; Min, H.; Min, S. Inter-relationship among risk taking propensity, supply chain security practices, and supply chain disruption occurrence. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2016, 22, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hintsa, J.; Uronen, K. Common Assessment and Analysis of Risk in Global Supply Chains. Technical Report Project: FP7-CASSANDRA. 2012. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/282845713_Common_Assessment_and_Analysis_of_Risk_in_Global_Supply_Chains (accessed on 28 May 2023).

- Urciuoli, L.; Ekwall, D. The perceived impacts of AEO security certifications on supply chain efficiency—A survey study using structural equation modelling. Int. J. Shipp. Transp. Logist. 2015, 7, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Criminal Police Organization. Global Crime Trend Report 2022 INTERPOL; International Criminal Police Organization: Lyon, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Moody’s Analytics. The Top 10 Supply Chain Risks That Companies Face, Supplier Risk Management, Supply Chain. Available online: https://www.moodysanalytics.com/articles/2022/the-top-10-supply-chain-risks-that-companies-face (accessed on 3 November 2022).

- What Inflation and Rising Prices Mean for Property Damage Insurance. Available online: https://www.zurich.com/en/commercial-insurance/sustainability-and-insights/commercial-insurance-risk-insights/what-inflation-and-rising-prices-mean-for-property-damage-insurance (accessed on 3 November 2022).

- Volmar, G. Puntos de inflación—Dos países pueden tener el mismo porcentaje y sufrir trastornos diferentes. Available online: https://www.diariolibre.com/economia/columnistas/2022/01/31/el-impacto-social-de-la-inflacion/1614701 (accessed on 3 November 2022).

- Global Slavery Index/Regional Findings the Americas. Available online: https://www.walkfree.org/global-slavery-index/findings/regional-findings/americas/ (accessed on 28 May 2023).

- Gutierrez, X.; Wieser, P.; Hintsa, J. Voluntary supply-chain security programme impacts: An empirical study with BASC member companies. In Risk Management in Port Operations, Logistics and Supply Chain Security; Informa Law from Routledge: London, UK, 2007; pp. 31–35. [Google Scholar]

- Hintsa, J. Study on BASC-program in Latin America (2005–2007); Cross-Border Research Association (CBRA): Échandens, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bichou, K. Risk-based Cost Assessment of Maritime and Port Security. In Security and Environmental Sustainability of Multimodal Transport; Bell, M., Hosseinloo, S.H., Kanturska, U., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 183–211. [Google Scholar]

- Costs and Benefits Survey. U.S. Customs Border and Protection. Available online: https://ctpatsecurity.com/wp-content/uploads/ctpat_css_survey-1.pdf (accessed on 28 May 2023).

- Sheu, C.L.; Niehoff, B. A Voluntary Logistics Security Program and International Supply Chain Partnership. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2006, 11, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thibault, M.; Brooks, M.R.; Button, K.J. The Response of the US Maritime Industry to the New Container Security Initiatives. Transp. J. 2006, 45, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gettinger, M. Everything You Need to Know about C-TPAT and Total Landed Cost. ThomasNet Industry News. 4 January 2021. Available online: https://www.thomasnet.com/insights/c-tpat-and-total-landed-cost/ (accessed on 28 May 2023).

| Reference | Security Initiatives | Focus | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C-TPAT | AEO | BASC | ISO 28000 | ||

| Ritchie and Melnyk (2012) [34] | X | Analysis of performance vs. level of investment in C-TPAT. | |||

| Melnyk et al. (2013) [35] | X | Decision factors for C-TPAT adoption. | |||

| Voss and Williams (2013) [36] | X | Relational security of public–private partnership (PPP) of C-TPAT. Focus is also given because C-TPAT encourages firms to voluntarily improve their security competence and that of their supply chain partners. | |||

| Herrera (2014) [37] | X | Evaluation of productivity in companies of the city of Cartagena certified in BASC, through productivity indicators. | |||

| Schramm (2015) [38] | X | Beneficiaries of the AEO program. | |||

| Blos et al. (2016) [39] | X | ISO 31000 as a complement to ISO 28000. | |||

| Ni et al. (2016) [40] | X | Motivations for the adoption of the C-TPAT program. | |||

| Chang-Bong et al. (2016) [41] | X | Factors to be taken into account when using an AEO program. | |||

| Herrera (2016) [42] | X | Evaluation of financial efficiency in BASC-certified companies in Cali, through a non-parametric approach and data envelopment analysis (DEA), specifically the CCR-O model, focused on results. | |||

| Souza et al. (2017) [43] | X | Impacts on international logistics for supply chain agents to ensure the AEO program—case of port terminals in Brazil. | |||

| Karlson (2017) [44] | X | The area of compliance management and identifies how the Authorized Economic Operator (AEO) instrument is about to transform into more mature and developed models. | |||

| Bagchi and PaulJomon (2017) [45] | X | Conducting a game between the government, an importer, and a terrorist group to measure the impact of the CTPAT program and its role in conjunction with other government policies such as espionage. | |||

| Houe and Murphy (2018) [46] | X | How an Authorized Economic Operator (AEO) certificate can affect the creation of a competitive advantage for a logistics service provider (freight forwarder) and its practical implications. | |||

| Burns (2018) [47] | X | Development of a “Participatory Operational Assessment” tool between the U.S. Department of Homeland Security and stakeholders to address operational and security challenges on both sides of the border and facilitate trade and resilience. | |||

| Chin and Sorooshian (2019) [48] | X | Identification and explanation of 16 barriers to ISO 28000 implementation. | |||

| Chin and Sorooshian (2019) [48] | X | Presents a list of pushes and pulls for the implementation of ISO 28000, considering that still many organizations in the Pahangque mining industry have not yet applied for this standard. | |||

| Dos Santos Marqués et al. (2019) [49] | X | Analysis of performance indicators related to international trade and cross-border operations from the Authorized Economic Operator (AEO) perspective. | |||

| Gupta et al. (2019) [50] | X | Empirical examination of the certification benefits associated with C-TPAT, the connection between the size of a company. The development of a framework based on drivers and barriers for companies to participate in the C-TPAT program rather than the commonly used cost–benefit analysis framework. | |||

| Erfan (2019) [51] | X | AEO programs should provide standard levels of measurable benefits that should be extended to include exemptions for certification of origin and proof of origin procedures that would provide certified companies with a competitive advantage. | |||

| Ing et al. (2019) [52] | X | Benefits to basic supply chain security that attracts industry to implement ISO 28000. | |||

| Kim et al. (2019) [53] | X | Analysis of the effect of the Authorized Economic Operator Mutual Recognition Agreement (AEO-MRA) on the performance of Korean exporters and importers. | |||

| Jażdżewska-Gutta et al. (2020) [54] | X | Motives and benefits of Authorized Economic Operator (AEO) certification in the supply chain. And significant differences in the perception of AEO status as a necessity or a privilege between cargo owners and service providers. | |||

| Zimon and Madzik (2020) [55] | X | The impact of standardized management systems (ISO 9001, ISO 14001, ISO 22000, and ISO 28000) in minimizing selected aspects of risk in the supply chain, regardless of the organization’s role in the supply chain. | |||

| Kusrini et al. (2021) [56] | X | Analysis of compliance and supply chain security risks and proposed mitigation based on ISO 28001 in a logistics service provider in Indonesia. | |||

| Kusrini and Hanim (2021) [57] | X | Analysis of compliance and supply chain security risks and proposed mitigation based on ISO 28001 in a logistics service provider in Indonesia. | |||

| Tong et al. (2022) [58] | X | Empirical study focusing on if and how the adoption of C-TPAT certification could improve the operational performance of adopting companies. | |||

| This paper | X | X | X | X | To identify the main characteristics, the benefits and the costs of implementation of the different available logistics security programs |

| Initiatives/Programs | Originating Actors | Actors in the International Supply Chain | Enforceability | Action/Response |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PIP (Canada) StairSec (Sweden) ACP & Frontline (Australia) AEO (European Union) | Governmental agencies | All | Voluntary | Adding a security layer to existing Customs Compliance programs |

| C-TPAT (USA) Secured Export Partnership (New Zealand) | Governmental agencies | All | Voluntary | Designing and implementing supply chain security programs |

| CSI Container Security Initiative. US customs officers control cargo in foreign ports before they arrive at US borders. | US government | Ports Terminal | Voluntary | Preventing threats at the source and using advance information |

| 24 h rule advance manifest rule and 96 h notification of arrival vessel. | Maritime Transportation | Mandatory | ||

| BASC (Latin America), Business Alliance for Secure Commerce. TAPA (Transported Asset Protection Association) against cargo theft. | Private sector | All | Voluntary | Companies with high-risk products or operating in risky regions designing security programs |

| ISPS (International Ship and Port Facility Security Code) by IMO. | International Organizations | Maritime Transportation | Mandatory | Establishing specific regulations for risky transport modes |

| Aviation security plan of action by ICAO. | Air Transportation | Mandatory | ||

| AEO—Authorized Economic Operator (WCO Framework of Standards to Secure and Facilitate Global Trade). | International Organizations | All | Voluntary | Establish security standards that can be generalized for the entire customs and trading community |

| ISO 28000–ISO 28001 (International organization for standardization) | International Organizations | All | Voluntary | Become the leading supply chain security management standard |

| Originating Actors | Program and Date of Launch | Number of Certified Companies in 2020 in the Americas and the Caribbean | Countries of Certified Companies | Scope |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| U.S. CBP | C-TPAT 2001 | 11.400 | United States Mexico Canada | U.S. importers/exporters; U.S./Canadian trucking carriers; U.S./Mexican trucking carriers; rail and ocean carriers; licensed U.S. customs brokers; U.S. marine terminal operators/port authorities; U.S. freight consolidators; ocean freight brokers; and non-operating common carriers; Mexican and Canadian manufacturers; and Mexican long-haul carriers. |

| WBO | BASC 2008 | 3.800 | Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Mexico, Panama, Peru, United States, Venezuela, and Guatemala. | Importers, exporters, shipping lines, container yards, logistics operators, marine/port terminals, free trade zones, security and surveillance companies, customs brokers, airports/airlines, and hotels. |

| WCO | AEO 2007 | 2.606 | Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Jamaica, Honduras, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, and Uruguay. | Importers, exporters, freight forwarders, customs agencies, logistic operators and other stakeholders. |

| ISO | ISO 28000 ISO 28001 2007 | 162 | Argentina, Bolivia Brazil, Colombia Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Guatemala Mexico, Peru, and Uruguay | Importers, exporters, maritime terminals, freight forwarders, carriers, logistics operators, border crossings. |

| Country | Program Title | Date of Launch | Type of Operator | Number of Operators | Authorities Involved in Certification | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Argentina | AEO | 2017 | Exporters, importers, customs brokers, customs freight forwarders, and inland freight forwarders related to foreign trade. | 49 | AFIP–DGA | Operative |

| Bolivia | AEO | 2015 | Exporters, importers, customs brokers, freight forwarders, freight consolidators and deconsolidators, bonded warehouse concessionaire. | 43 | National Customs | Operative |

| Brasil | AEO | 2014 | Importer, exporter, freight forwarders, customs bonded warehouses, port and airport operators, transporters, Special Precinct for Customs Export Clearance (REDEX). | 490 | Receita Federal, ANVISA, VIGIAGRO, Army, ANAC, INMETRO (the last 3 under development) | Operative |

| Chile | AEO | 2017 | Exporters, importers, customs brokers, and postal service providers PSP/couriers. | 19 | National Customs Service. | Operative |

| Colombia | AEO | 2011 | Exporters, importers, customs agents, and ports Gradually incorporating other operators. | 201 | DIAN, ICA, INVIMA, National Police, Ministry of Transportation, and DIMAR | Operative |

| Costa Rica | Customs Facilitation for Reliable Trade Program (PROFAC) | 2011 | Exporters, importers, port operators, and export cargo terminals. | 30 | Ministry of Finance, Agriculture and Health (under negotiation) | Operative |

| Cuba | AEO | 2016 | Exporters and importers. | 4 | General Customs of the Republic | Operative |

| Ecuador | AEO | 2015 | Exporters and importers. | 6 | SENAE | Operative |

| El Salvador | El Salvador Authorized Economic Operator—AEO-SV | 2015 | Exporters, importers, customs brokers, bonded warehouse operators, postal service providers PSP/couriers, and gradually incorporating other operators. | 2 | Ministry of Finance | Operative |

| Guatemala | Guatemala Authorized Economic Operator AEO-GT | 2011 | All actors along the supply chain. | 50 | SAT | Operative |

| Jamaica | AEO | 2014 | Importers. | 136 | Customs, Health and Agriculture Agency | Operative |

| Honduras | AEO | 2020 | Exporters/importers. Gradually incorporating other operators. | 0 | Honduras Customs Administration | Operative |

| Mexico | AEO | 2012 | Exporters/importers, customs brokers, inland trucking, bonded warehouses, strategic bonded warehouses, couriers and parcels, industrial parks and logistics outsourcing. | 1.073 | General Administration of Foreign Trade Auditing of the SAT | Operative |

| Panama | AEO | 2013 | Importers, customs brokers, freight forwarders, warehouses and bonded warehouses, postal service providers PSP/couriers and logistics service providers. | 27 | Customs and all border agencies are considered support and control entities | Operative |

| Paraguay | AEO | 2018 | Exporters, importers, customs agents. Gradually incorporating other operators. | 1 | National Customs Office | Operative |

| Perú | AEO | 2012 | Exporters, importers, customs brokers, bonded warehouses, express delivery service companies. | 164 | SUNAT | Operative |

| Dominican Republic | AEO | 2012 | Exporters, importers, freight consolidators, customs brokers, warehouse operators, Free Trade Zones, manufacturers, seaports, airports and maritime transportation. | 246 | DGARD, Health, Agriculture, Environment, Drugs, CESPA, and the CNZFE | Operative |

| Uruguay | OEC Qualified Economic Operator (QEO) | 2014 | All actors in the supply chain. | 65 | National Customs Office | Operative |

| Venezuela | AEO | 2014 | Producers, manufacturers, importers, exporters, customs brokers, warehouses and bonded warehouses, postal service providers PSP/couriers, shipping agents, and port operators. | -- | SENIAT | Under development |

| Major Moments in Supply Chains | Security Risks |

|---|---|

| Loading of trucks or other transportation means | During loading of containers onto transportation means, effective measures must ensure that neither weapons, nor explosives, nor other prohibited materials are introduced into containers. |

| Transportation, transshipment, and warehousing. | During transportation, the major concern is for the cargo not to be tampered with and so, the declared goods remain those, and only those, carried in the shipment. |

| Unloading/receiving of shipments and containers | Upon unloading/receiving of a shipment, security measures ensure that no undeclared items are added to a shipment, and also that declared items are not subtracted from the cargo. Security measures must ensure that only authorized personnel perform the intended operations, which guarantee that the declared goods are indeed those carried in a shipment. |

| Trends | Americas and the Caribbean Crime Trends | Security Risks for Global Supply Chains | Actions Proposed by Logistics Security Programs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organized Crime |

| This threat from organized crime can be represented in different types of risks for supply chains, such as extortion, bribery, corruption, sabotage, information theft, cargo theft, and smuggling, among others. | Establish a risk management system focused on the international supply chain that anticipates illicit activities generated by organized crime, including money laundering, drug trafficking and terrorist financing, extortion, bribery, corruption, sabotage, information theft, cargo theft, smuggling, drug trafficking, cargo contamination, arms trafficking, human trafficking, and terrorism, among others. To have a demanding selection and continuous monitoring of business partners (suppliers and customers), to protect themselves from illegal activities or being involved in incidents of contamination of their supply chains. Implement oriented measures to maintain the integrity of the container and other cargo units, as well as the means of transport, in order to prevent the occurrence of security incidents. Have access control to the company’s facilities, which includes control measures to prevent unauthorized access to the facilities, maintain control of employees and visitors, and protect the company’s assets. As well as measures to ensure the security of all its facilities (surveillance and control of the exterior and interior perimeters). Have a personnel selection process to guarantee the knowledge of its employees. Have procedures in place to ensure the integrity and security of the processes related to the handling, storage, and transportation of cargo in the supply chain. It must have tools to ensure the traceability of the cargo from the filling point abroad to the importer’s headquarters or from the warehouse to the buyer’s headquarters, through satellite seals, GPS, RFID for the security of products and information within a global supply chain. Having tools to report to the competent authority in cases where irregularities or illegal or suspicious activities are detected in their international supply chains. Have measures in place to protect unauthorized access to information, documentation, and their IT systems, to maintain the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of information on their operations. Implement training programs for employees at all levels to develop the ability to maintain supply chain security by recognizing internal and external threats at every point in the chain. |

| Illicit Trafficking |

| This threat from illicit trafficking can be represented in different types of risks to supply chains, such as drug trafficking, cargo contamination, arms trafficking, and human trafficking. | |

| Financial Crime and Corruption |

| This threat of financial crime and corruption can be represented in different types of risks for supply chains, such as money laundering and financing of terrorism through business relationships with suppliers and customers. | |

| Cybercrime |

| This Cybercrime threat can be represented in different types of risks to supply chains, such as these: Cybercrime includes individual actors or groups attacking systems for financial gain or illicitly causing disruption. Cyber-attacks often involve information gathering for political, economic and/or reputational purposes. Cyberterrorism aims to weaken electronic systems to cause panic or fear. | |

| Terrorism |

| This threat of terrorism can be represented in different types of risks for supply chains, such as terrorist actions that consider the use of means of transportation (including the container) and facilities as a weapon or containment device for explosive, radioactive, or contaminating elements. |

| Type of Risk | Risk Description | Security Risks for Global Supply Chains | Actions Proposed by Logistics Security Programs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural disasters (Moody’s Analytics Insights, 2022) [76] |

| Supply chains are vulnerable to property damage and business disruption due to natural disasters. Companies need to quantify the financial and operational impact in real time and assess site-specific risks. These events lend themselves to criminal activity, such as looting, theft, and robbery of goods on the premises and/or in transport. | To have a plan that guarantees the continuity of its operations in the event of natural disasters, fires, power outages, communication and transportation failures, viruses, and inflation. Establish emergency and recovery plans for natural disasters. Protocols for unexpected events in land cargo transportation including unexpected stops, theft or looting of the vehicle, route deviation, road blockage, traffic accident, mechanical failure, and violation of security seals. Biosecurity protocols for the prevention and propagation of biological risks. |

| Biological |

| The biosecurity measures established by supply chain actors can have an indirect impact on the physical security of their facilities, since access controls are reduced through the use of identification cards or biometric readers that allow the registration of personnel entry and exit. Likewise, facial registration is reduced by the mandatory use of face masks through monitoring and surveillance systems. | |

| Inflation (Zurich Insurance Group Ltd., 2022) [77] |

| If left unchecked, inflation can result in a severe loss of consumer or organizational purchasing power. This generates a social impact in developed and emerging countries. For the former, inflation could manifest itself, for example, in the form of higher prices for appliances, recreation, meat, travel, or motor vehicles. For the other, it could be that the prices that are rising the most are those of fuels, basic foodstuffs, and electric power [78,79], and this could somehow lead to a social standoff, where looting, theft from shops, and robbery in the transportation network could occur. | |

| Forced Labor (Global Slavery Index—GSI, 2023) [79] |

| Vulnerability to modern slavery in the Americas region is largely due to inequality, political instability and discrimination against migrants and minority groups. This risk can be represented by a supplier or subcontractor in the supply chain being linked to forced labor. | Conduct a review of the hiring processes of personnel linked to their suppliers and/or subcontractors. If there is any link to forced labor activity, companies should terminate contracts and relationships with these suppliers and report them to the competent authorities as part of their social responsibility policy. |

| C-TPAT | BASC | SAFE Framework—AEO | ISO 28000 | ISO 28001 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BASC norm:

|

SAFE Framework of Standards World Customs Organization—WCO. ANNEX V: Resolution of the Customs Cooperation Council on the SAFE Framework of Standards to Secure and Facilitate World Trade (version 2021). |

|

|

| Chapter/Item | Security Objectives | ID/Principal Minimum Security Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Risk management. | Manage risks through context analysis, risk assessment, risk treatment, monitoring, and review to mitigate the likelihood and impact of security risks to which global supply chains are exposed and be consistent with security policies. | 1.1 Must have a security management policy focused on risk assessment to ensure supply chain security. 1.2 The policy should have security management objectives, goals, and programs. 1.3 It should have a risk management system focused on the supply chain. 1.4 It should disseminate the security policy to stakeholders through the company’s website, be posted within the company (bulletin board, email, etc.) in key locations. 1.5 Should have documented procedures for crisis management, business continuity and recovery plans. |

| 2. Knowledge of business partners/business associates. | Ensure a reliable selection and evaluation of business partners (customers and suppliers) to protect against activities related to money laundering and terrorist financing, as well as those actions that may affect the security and integrity of the goods carried out by logistics operators. | 2.1 Must have documented procedures for purchasing, selection, and contracting of suppliers that guarantee their reliability. 2.2 Must have documented procedures for customer selection and contracting that guarantee their reliability. 2.3 It must carry out security visits to the facilities where its business partners carry out their operations, to verify that they have implemented security measures in the international supply chain. 2.4 It must issue security agreements for those trading partners that do not have security program certificates from other international public or private organizations. 2.5 The company and its members (managers) should have their background checked against national and international lists for the prevention of crimes related to money laundering and terrorism. |

| 3. Conveyance and transportation unit security. | Maintain the integrity of containers and other cargo units, as well as means of transport, to protect them against the occurrence of security incidents. | 3.1 Must have documented procedures and controls to ensure the integrity of containers and other cargo units at the point of filling to protect them against the introduction of unauthorized persons or materials. 3.2 Shall use security seals under the standards contained in the current ISO 17712 standard on containers and other sealable cargo units. 3.3 Inspect the physical integrity of the container structure (internal and external) and other cargo units, as well as the means of transport. A documentary record of the inspection shall be kept by the person responsible for the activity. 3.4 Ensure that the areas where containers and other cargo units (full or empty) are stored are secure and prevent unauthorized access and/or manipulation. 3.5 Have procedures in place to detect and report unauthorized entry to containers and other cargo units, as well as when security seals have been breached. |

| 4. Physical access controls and physical security. | Prevent unauthorized access to the facilities and ensure the security of the facilities through surveillance and perimeter control, especially in critical areas of the company. | 4.1 Have documented procedures and measures to identify and control access of people and vehicles to the facilities. 4.2 Provide all related personnel with an identification or access device for entry to the facilities. 4.3 Require visitors to identify themselves for entry to the facilities and provide them with an identification or temporary access device. 4.4 Check persons, vehicles, packages, bags, and other objects upon entering and leaving the facilities. 4.5 Must use alarm systems and/or video surveillance cameras to monitor, alert, record, and supervise the facilities and prevent unauthorized access to critical areas and cargo handling, inspection or storage areas. |

| 5. Safety in the processes related to handling, storage, and conveyance. | Ensure the integrity, safety and traceability of the processes related to the handling, storage and transportation of cargo in the supply chain. | 5.1 Must have documented procedures for handling, storage and transportation of cargo. 5.2 Must have tools to ensure traceability of the cargo and the vehicle transporting it from the point of filling to the port of shipment to the outside (downstream). 5.3 Must have tools to ensure traceability of the cargo from the point of filling abroad to the importer’s headquarters or distribution point (upstream). 5.4 Must have a protocol to act and report suspicious activities or security incidents that affect the security of the supply chain to the competent authority. 5.5 You must protect the physical and electronic documentation of your international supply chain operations. |

| 6. Personnel security. | Ensure the reliability of its employees through procedures that allow you to know the personnel linked and the definition of critical positions within the company. | 6.1 It shall have documented procedures for the selection and dismissal of personnel. 6.2 It shall evaluate the background of employees in national and international lists to ensure their reliability. 6.3 Maintain updated employee work history, including personal and family data, photographic records, and background checks, among others. 6.4 Must carry out home visits and socioeconomic studies of its employees to detect unjustified changes in their assets. 6.5 Must have security provisions for the supply and handling of the supplies given to its employees. |

| 7. Information technology security. | Establish IT security measures to protect the company’s information, data, networks and programs against cybercrime, cyberattacks and cyberterrorism. | 7.1 Have documented and sensitized IT security policies within the company to protect information technology (IT) systems. 7.2 It must contemplate software programs and equipment to protect against common external cybersecurity threats (viruses, worms, spyware, Trojans, and hackers, among others) and against internal threats of theft or leakage of information through the use of USB or storage devices, emails, and unintentional human error. 7.3 It must assign individual access accounts to the technological platform, with periodic changes of passwords with n characteristics that increase security levels. 7.4 It must have an IT contingency plan that guarantees the integrity, confidentiality, and availability of the company’s information. 7.5 It must have a defined area (computer center) with appropriate security measures that guarantee access only to authorized personnel. |

| 8. Education, training, and awareness. | Strengthen the security culture through periodic training and education programs on security, threats and risks. | 8.1 A periodic induction and re-induction program should be in place for all employees on the company’s security measures. 8.2 It shall have specialized training programs on security, threats, and risks to prevent and act against any criminal activity that affects the continuity of its supply chain operations. 8.3 Must have an alcohol and drug use prevention program in place. 8.4 It shall have a program of drills for crisis management, business continuity, and emergency plans. 8.5 An induction program shall be in place for visitors and contractors, where applicable, to ensure that they are aware of the company’s security measures and possible threats and risks. |

| Chapter—Minimum Security Criteria/Security Program | C-TPAT | BASC | SAFE Framework AEO | ISO |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Risk management. | ||||

| 1.1 Must have a security management policy focused on risk assessment to ensure supply chain security. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1.2 The policy should have security management objectives, goals and programs. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1.3 It should have a risk management system focused on the supply chain. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1.4 It should disseminate the security policy to stakeholders through the company’s website, and be posted within the company (bulletin board, email, etc.) in key locations. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1.5. Should have documented procedures for crisis management, business continuity, and recovery plans. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2. Knowledge of business partners/business associates. | ||||

| 2.1 Must have documented procedures for purchasing, selection, and contracting of suppliers that guarantee their reliability. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2.2 Must have documented procedures for customer selection and contracting that guarantee their reliability. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2.3 It must carry out security visits to the facilities where its business partners carry out their operations, to verify that they have implemented security measures in the international supply chain. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2.4 It must issue security agreements for those trading partners that do not have security program certificates from other international public or private organizations. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2.5 The company and its members (managers) should have their background checked against national and international lists for the prevention of crimes related to money laundering and terrorism. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 3. Conveyance and transportation unit security. | ||||

| 3.1 Must have documented procedures and controls to ensure the integrity of containers and other cargo units at the point of filling to protect them against the introduction of unauthorized persons or materials. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 3.2 Shall use security seals under the standards contained in the current ISO 17712 standard on containers and other sealable cargo units. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 3.3 Inspect the physical integrity of the container structure (internal and external) and other cargo units, as well as the means of transport. A documentary record of the inspection shall be kept by the person responsible for the activity. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 3.4 Ensure that the areas where containers and other cargo units (full or empty) are stored are secure and prevent unauthorized access and/or manipulation. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 3.5 Have procedures in place to detect and report unauthorized entry to containers and other cargo units, as well as when security seals have been breached. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 4. Physical access controls and physical security. | ||||

| 4.1 Have documented procedures and measures to identify and control access of people and vehicles to the facilities. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 4.2 Provide all related personnel with an identification or access device for entry to the facilities. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 4.3 Require visitors to identify themselves for entry to the facilities and provide them with an identification or temporary access device. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 4.4 Check persons, vehicles, packages, bags, and other objects upon entering and leaving the facilities. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 4.5 Must use alarm systems and/or video surveillance cameras to monitor, alert, record, and supervise the facilities and prevent unauthorized access to critical areas and cargo handling, inspection, or storage areas. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 5. Safety in the processes related to handling, storage, and conveyance. | ||||

| 5.1 Must have documented procedures for handling, storage, and transportation of cargo. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 5.2 Must have tools to ensure traceability of the cargo and the vehicle transporting it from the point of filling to the port of shipment to the outside (downstream). | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 5.3 Must have tools to ensure traceability of the cargo from the point of filling abroad to the importer’s headquarters or distribution point (upstream). | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 5.4 Must have a protocol to act and report suspicious activities or security incidents that affect the security of the supply chain to the competent authority. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 5.5 You must protect the physical and electronic documentation of your international supply chain operations. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 6. Personnel security. | ||||

| 6.1 It shall have documented procedures for the selection and dismissal of personnel. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 6.2 It shall evaluate the background of employees in national and international lists to ensure their reliability. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 6.3 Maintain updated employee work history, including personal and family data, photographic records, and background checks, among others. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 6.4 Must carry out home visits and socioeconomic studies of its employees to detect unjustified changes in their assets. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 6.5 Must have security provisions for the supply and handling of the supplies given to its employees. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 7. Information technology security. | ||||

| 7.1 Have documented and sensitized IT security policies within the company to protect information technology (IT) systems. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 7.2 It must contemplate software programs and equipment to protect against common external cybersecurity threats (viruses, worms, spyware, Trojans, hackers, among others). And internal threats of theft or leakage of information through the use of USB or storage devices, emails, and unintentional human error. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 7.3 It must assign individual access accounts to the technological platform, with periodic changes of passwords with n characteristics that increase security levels. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 7.4 It must have an IT contingency plan that guarantees the integrity, confidentiality, and availability of the company’s information. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 7.5 It must have a defined area (computer center) with appropriate security measures that guarantee access only to authorized personnel. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 8. Education, training, and awareness. | ||||

| 8.1 A periodic induction and re-induction program should be in place for all employees on the company’s security measures. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 8.2 It shall have specialized training programs on security, threats, and risks to prevent and act against any criminal activity that affects the continuity of its supply chain operations. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 8.3 Must have an alcohol and drug use prevention program in place. | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 8.4 It shall have a program of drills for crisis management, business continuity, and emergency plans. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 8.5 An induction program shall be in place for visitors and contractors, where applicable, to ensure that they are aware of the company’s security measures and possible threats and risks. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Degree of similarity with the General Logistics Security Management Framework | 98% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| Initiatives | Periodic Assessment | Certifying Agency | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Public Sector | Private Sector | ||

| C-TPAT | 1 year | X | |

| BASC V6 | 1 year | X | |

| AEO | 2–3 years | X | |

| ISO 28000–ISO 28001 | 1 year | X | |

| C-TPAT | BASC | AEO | ISO 28000–28001 |

|---|---|---|---|

The program includes the following benefits for supply chain actors:

| The program defines the following benefits for companies participating in the international supply chain:

| At the international level, most programs offer the following benefits:

| Benefits that attract companies in the implementation of ISO 28000 to secure the supply chain:

|

| Annual Turnover USD | Number of Companies | Average Value in USD | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Implementation Cost USD | Annual Maintenance USD | Maintenance/Certification Cost | Certification Cost/Turnover | ||

| <50,000 | 4 | 28.625 | 2.888 | 10% | ≥57% |

| 50,000–500,000 | 13 | 17.176 | 8.539 | 50% | 3–34% |

| 500,000–1 million | 13 | 13.585 | 6.698 | 49% | 1–3% |

| 1–5 million | 25 | 61.820 | 15.826 | 26% | 1–6% |

| >5 million | 35 | 52.742 | 28.448 | 54% | ≤1% |

| Total | 90 | 34.790 | 12.487 | 38% | |

| Time | Average Values |

|---|---|

| Months necessary for certification process | 8 |

| Total hours of work for certification | 2.337 |

| Resources | |

| Number of employees involved in certification process | 48 |

| Number of employees involved/Total employees | 23% |

| Time per resource | |

| Hours per person | 49 (~6 working days) |

| Research | Monetary Cost |

|---|---|

| Bichou [83] | At the beginning of the program in 2004, the average implementation cost was estimated at USD 200,000, and the average maintenance cost was USD 113,000. However, over time, the implementation and maintenance costs have reduced. |

| CBP [84] | Average implementation cost USD 38,471 and average maintenance cost USD 69,000. |

| CBP:2011 [84] | A subsequent study conducted by CBP in 2010 further reports that the implementation of physical security is the most significant factor in estimating certification costs, while the maintenance of physical security/cargo is the most important factor in calculating maintenance costs. The average implementation cost reported is USD 137,899 (with a median of USD 17,370), and the average maintenance cost is USD 47,749 (with a median of USD 9000). |

| Sheu et al. [85] | Another study examined the initial monetary costs and time commitments by interviewing four C-TPAT certified companies, including a broker, an import service provider, a carrier/transporter, and an importer. Their study reports that the initial certification cost ranges from USD 3500 to USD 18,000, with a time commitment varying between 160 and 210 days. |

| Thibault et al. [86] | They also found that smaller companies may have lower compliance costs. Furthermore, they discovered that smaller ocean carriers had lower implementation costs but incurred higher maintenance costs compared to larger ocean carriers. |

| Gettinger [87] | For importers, on average, there are three implementation costs they incur, with an average implementation cost of USD 39,500 represented by the following components: Physical security: USD 15,000. IT systems: USD 12,500. Additional salaries: USD 12,000. |

| Ni et al. [40] | The initial implementation and maintenance costs for early adopters were substantial due to the lack of best practices. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mora Lozano, P.E.; Montoya-Torres, J.R. Global Supply Chains Made Visible through Logistics Security Management. Logistics 2024, 8, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/logistics8010006

Mora Lozano PE, Montoya-Torres JR. Global Supply Chains Made Visible through Logistics Security Management. Logistics. 2024; 8(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/logistics8010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleMora Lozano, Pablo Emilio, and Jairo R. Montoya-Torres. 2024. "Global Supply Chains Made Visible through Logistics Security Management" Logistics 8, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/logistics8010006

APA StyleMora Lozano, P. E., & Montoya-Torres, J. R. (2024). Global Supply Chains Made Visible through Logistics Security Management. Logistics, 8(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/logistics8010006